Pan-European identity

Pan-European identity is the sense of personal identification with Europe, in a cultural or political sense. The concept is discussed in the context of European integration, historically in connection with hypothetical proposals, but since the formation of the European Union (EU) in the 1990s increasingly with regards to the project of ever-increasing federalisation of the EU.

Pan-European identity has roots as far back as the Middle Ages, when poet and political advisor Dante Alighieri claimed, "My country is the whole world."[1] Much of its foundational definition emerged during the Renaissance. Artists and scholars of that period collaborated across national boundaries, travelling to centres of activity in their respective fields and believing that freedom came from common bonds and individualism in a way that transcended national allegiances.[2]

Developing of Pan-European identity continued during the Enlightenment. During this time, leading philosophical and political thinkers in Europe articulated a form of nationalism that acknowledged local cultural differences while incorporating a sense of shared, universal values based on the application of reason. Towards the end of the Eighteenth Century, philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau remarked that "there are no longer any Frenchmen, Germans, Spaniards, or even Englishmen; there are only Europeans."[3] Irish statesman and political theorist Edmund Burke spoke of a "European Commonwealth" brought together by commercial and economic bonds, and in 1976 wrote: "No citizen of Europe could be altogether an exile in any part of it... When a man travelled or resided for health, pleasure, business or necessity, from his country, he never felt himself quite abroad."[4][3]

The model of a "pan-European" union is the Carolingian Empire, which united "Europe" in the sense of Latin Christendom.

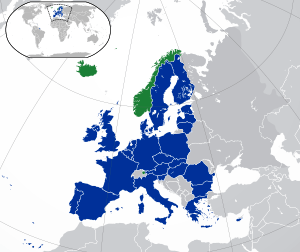

The original proposal for a Paneuropean Union was made in 1922 by Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi. The term "Pan-European" is to be understood not as referring to the modern geographic definition of the continent of Europe but in the historical sense of the western parts of continental Europe sharing the common history of Latin Christendom, the Carolingian Empire and the early modern Habsburg Empire. Coudenhove-Kalergi saw the Pan-European state as a future "fifth great power", in explicit opposition to the Soviet Union, "Asia", Great Britain and the United States (as such explicitly excluding both the British Isles and Eastern Europe from his notion of "Pan-European").[5]

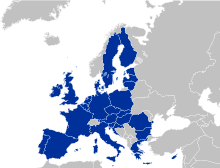

After 1945, an accelerating process of European integration culminated in the formation of the European Union (EU) in 1993. In the period of 1995–2013, the EU has been enlarged from 12 to 28 member states, far beyond the area originally envisaged for the "pan-European" state by Coudenhove-Kalergi (with the exception of Switzerland), its member states accounting for a population of some 510 million, or two thirds of the population of the entire continent.

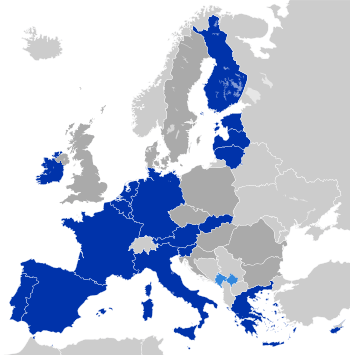

In the 1990s to 2000s, there was an active movement towards a federalisation of the European Union, with the introduction of symbols and institutions usually reserved for sovereign states, such as citizenship, a common currency (used by 19 out of 28 members), a flag, an anthem and a motto (In Varietate Concordia, "United in Diversity"). An attempt to introduce a European Constitution was made in 2004, but it failed to be ratified; instead, the Treaty of Lisbon was signed in 2007 in order to salvage some of the reforms that had been envisaged in the constitution.

A debate on the feasibility and desirability of a "pan-European identity" or "European identity" has taken place in parallel to this process of political integration. The ideology of pan-European nationalism, which had been a hallmark of neo-fascist or far-right currents of European politics during the 1950s to 1970s, has been largely abandoned in favour of a resurgence of national identity paired with "Euroscepticism", while the proponents of European integration do not connect the "European idea" with nationalism, but rather with a "postmodern world order" characterised by "diversity of identity" combined with a "commonality of values".[6] while the remaining loyalties to national or cultural identities are seen as a threat to the "supranational prospect" of European integration.[7]

A possible future "European identity" is seen at best as one aspect of a "multifaceted identity" still involving national or regional loyalties. Two authors writing in 1998 concluded that "In the short-term it seems that the influence of this project [of European integration] will only influence European identity in certain limited niches and in a very modest way. It is doubtful if this will do to ensure a smooth process of ongoing European integration and successfully address the challenges of the multicultural European societies."[8] Even at that time, the development of a common European identity was viewed as rather a by-product than the main goal of the European integration process, even though it was actively promoted by both EU bodies and non-governmental initiatives, such as the Directorate-General for Education and Culture of the European Commission. [8][9] With the rise of EU-scepticism and opposition to continued European integration by the early 2010s, the feasibility and desireability of such a "European identity" has been called into question.[10]

History of Pan-Europeanism

Pan-Europeanism, as it emerged in the wake of World War I, derived a sense of European identity from the idea of a shared history, taken to be the source of a set of fundamental "European values".

Typically the 'common history' includes a combination of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, the feudalism of the Middle Ages, the Hanseatic League, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, 19th century liberalism and different forms of socialism, Christianity and secularism, colonialism and the World Wars.

The oldest European unification movement is the Paneuropean Union, founded in 1923 with the publishment of Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi's book Paneuropa, who also became its first president (1926–1972), followed by Otto von Habsburg (1973–2004) and Alain Terrenoire (from 2004). This movement initiated and supported the "integration process" pursued after World War II, which eventually led to the formation of the European Union. Notable "Paneuropeans" include Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Alcide De Gasperi.

European values

Especially in France, "the European idea" (l'idée d'Europe) is associated with political values derived from the Age of Enlightenment and the Republicanism growing out of the French Revolution and the Revolutions of 1848 rather than with personal or individual identity formed by culture or ethnicity (let alone a "pan-European" construct including those areas of the continent never affected by 18th-century rationlism or Republicanism).[11]

The phrase "European values" arises as a political neologism in the 1980s in the context of the project of European integration and the future formation of the European Union. The phrase was popularised by the European Values Study, a long term research program started in 1981, aiming to document the outlook on "basic human values" in European populations. The project had grown out of a study group on "values and social change in Europe" initiated by Jan Kerkhofs, and Ruud de Moor (Catholic University in Tilburg).[12] The claim that the people of Europe have a distinctive set of political, economic and social norms and values which are gradually replacing national values has also been named "Europeanism" by McCormick (2010).[13]

"European values" were contrasted to non-European values in international relations, especially in the East–West dichotomy, "European values" encompassing individualism and the idea of human rights in contrast to Eastern tendencies of collectivism. However, "European values" were also viewed critically, their "darker" side not necessarily leading more peaceful outcomes in international relations.[14]

The association of "European values" with European integration as pursued by the European Union came to the fore with the eastern enlargement of the EU in the aftermath of the Cold War. [15]

The Treaty of Lisbon (2007) in article 2 lists a number of "values of the Union", including "respect for freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights including the rights of persons belonging to minorities", invoking "a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail".[16]

The 2012 Eurobarometer survey reported that 49% of those surveyed described the EU member states as "close" in terms of "shared values" (down from 54% in 2008), 42% described them as "different" (up from 34% in 2008).[17]

In popular culture

Aspects of an emerging "European identity" in popular culture may be seen in the introduction of "Pan-European" competitions such as the Eurovision Song Contest (since 1956), the UEFA European Championship (since 1958) or, more recently, the European Games (2015). In these competitions, it is still teams or representatives of the individual nations of Europe that are competing against one another, but a "European identity" may argued to arise from the definition the "European" participants (often loosely defined, e.g. including Morocco, Israel and Australia in the case of the Eurovision Song Contest), and the emergence of "cultural rites" associated with these events.[18] In the 1990s and 2000s, participation in the Eurovision Song Contest was to some extent perceived as a politically significant confirmation of nationhood and of "belonging to Europe" by the then-recently independent nations of Eastern Europe.[19]

Pan-European events not organised along national lines include the European Film Awards, presented annually since 1988 by the European Film Academy to recognize excellence in European cinematic achievements. The awards are given in over ten categories, of which the most important is the Film of the year. They are restricted to European cinema and European producers, directors, and actors.[20]

The Ryder Cup golf competition is a biennial event, originally between a British and an American team, but since 1979 admitting continental European players to form a "Team Europe".

The flag of Europe was used to represent "Team Europe" since 1991, but reportedly most European participants preferred to use their own national flags.[21]

There have also been attempts to use popular culture for the propagation of "identification with the EU" on the behalf of the EU itself. These attempts have proven controversial. In 1997, the European Commission distributed a comic strip titled The Raspberry Ice Cream War, aimed at children in schools. The EU office in London declined to distribute this in the UK, due to an expected unsympathetic reception for such views.[22][23] Captain Euro, a cartoon character superhero mascot of Europe, was developed in the 1990s by branding strategist Nicolas De Santis to support the launch of the Euro currency.[24][25][26] In 2014, London branding think tank, Gold Mercury International, launched the Brand EU Centre, with the purpose of solving Europe’s identity crisis and creating a strong brand of Europe.[27][28] There have been proposals to create a European Olympic Team, which would break with the existing organisation through National Olympic Committees.[29] In 2007, European Commission President Romano Prodi suggested that EU teams should carry the EU flag, alongside the national flag, at the 2008 Summer Olympics – a proposal which angered eurosceptics.[30][31] According to Eurobarometer surveys, only 5% of respondents think that a European Olympic team would make them feel more of a 'European citizen'.[32]

The .eu domain name extension was introduced in 2005 as a new symbol of European Union identity on the World Wide Web. The .eu domain's introduction campaign specifically uses the tagline "Your European Identity". Registrants must be located within the European Union.

See also

- Symbols of Europe

- Symbols of the European Union

- Brand EU

- Captain Euro

- Continentalism

- Europe a Nation

- Eurocentrism

- The European Dream (2004)

- Paneuropean Union

- Pan-European nationalism

- Pan-nationalism

- European integration

- Europeanisation

- Europeanism

- Euroscepticism

- Federalisation of the European Union

- Fourth Reich

- Potential Superpowers – European Union

- Pre-1945 ideas on European unity

- Pro-Europeanism

- United States of Europe

References

- ↑ Gafijczuk, Dariusz (7 December 2016). "Europe has never liked borders – and it won't be confined by them now". The Conversation. United Kingdom. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ↑ Burckhardt, Jacob (1867). The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy [Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien] (in German). Switzerland.

- 1 2 Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A history. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780198201717.

- ↑ Welsh, J. (1995). Edmund Burke and International Relations: The Commonwealth of Europe and the Crusade against the French Revolution. Springer. p. 73. ISBN 9780230374829.

- ↑ "Eine Wiederherstellung der europäischen Weltherrschaft ist unmöglich; wohl aber ist es noch möglich, durch Zusammenfassung der europäischen Staaten diesen Erdteil zu einer fünften Weltmacht zusammenzuschliessen und so den Frieden, die Freiheit und den Wohlstand der Europäer zu retten." Coudenhove-Kalergi, Paneuropäisches Manifest (1923).

- ↑ "Nationalism was dead, but it was not replaced by pan-European nationalism or by a pan-European identity", the "European idea" being transformed into an idea of "diversity of identity" combined with a "commonality of values" Anton Speekenbrink, "Trans-Atlantic Relations in a Postmodern World" (2014), p. 258.

- ↑ "The supranational prospect held out by the EU appears to be threatened.... by a deficiency of European identity, in striking contrast to the continuing vigour of national identities, ...." Anne-Marie Thiesse. Inventing national identity.

- 1 2 Dirk Jacobs and Robert Maier, European identity: construct, fact and fiction Archived 19 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. in: A United Europe. The Quest for a Multifaceted Identity (1998) pp. 13-34.

- ↑ Pinterič, Uroš (2005). "National and supranational identity in context of the European integration and globalization". Društvena istraživanja. 14 (3): 401–402.

- ↑ Kenneth Keulman, Agnes Katalin Koós, European Identity: Its Feasibility and Desirability (2014)

- ↑ Marita Gilli, L'idée d'Europe, vecteur des aspirations démocratiques: les idéaux républicains depuis 1848 : actes du colloque international organisé à l'Université de Franche-Comté les 14, 15 et 16 mai 1992 (1994).

- ↑ Serendipities 2.2017 (1): 50–68 | DOI: 10.25364/11.2:2017.1.4 50ARTICLE Kristoffer Kropp, The cases of the European Values Study and the European Social Survey—European constellations of social science knowledge production, Serendipities 2.2017 (1): 50–68, DOI: 10.25364/11.2:2017.1.4.

- ↑ John McCormick, Europeanism (Oxford University Press, 2010)

- ↑ Vilho Harle, European Values in International Relations , 1990, i–x (preface).

- ↑ Adrian G. V. Hyde-Price, The International Politics of East Central Europe, Manchester University Press, 1996, p. 60. "The new nationalist myth in Eastern Europe thus attempts to define contemporary national identity in terms of European values and a European cultural heritage. The desire to return to Europe and embrace European values has led to a growing acceptance in much of East Central Europe of liberal democracy, human rights, multilateral cooperation and European integration."

- ↑ Treaty on the European Union, Title I: Common Provisions.

- ↑ LES VALEURS DES EUROPÉENS, Eurobaromètre Standard 77 (2012), p. 4.

- ↑ "Eurovision is something of a cultural rite in Europe." Archived 10 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "We are no longer knocking at Europe’s door," declared the Estonian Prime Minister after his country’s victory in 2001. "We are walking through it singing... The Turks saw their win in 2003 as a harbinger of entry into the EU, and after the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, tonight’s competition is a powerful symbol of Viktor Yushchenko’s pro-European inclinations." Oj, oj, oj! It's Europe in harmony. The Times, 21 May 2005. ""This contest is a serious step for Ukraine towards the EU," Deputy Prime Minister Mykola Tomenko said at the official opening of the competition." BBC, Ukrainian hosts' high hopes for Eurovision

- ↑ http://www.europeanfilmawards.eu/

- ↑ "While some fans of the European players in golf's Ryder Cup unfurl the flag of the European Union, many persist in waving their national flags despite the multinational composition of the European team." Alan Bairner, Sport, Nationalism, and Globalization: European and North American Perspectives (2001), p. 2.

- ↑ Archived 11 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Captain Euro". The Yes Men. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Designweek, 19 February 1998. Holy Bureaucrat! It's Captain Euro! Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://www.designweek.co.uk/news/holy-bureaucrat-its-captain-euro/1120069.article

- ↑ Wall Street Journal, 14 December 1998. Captain Euro will teach children about the Euro, but foes abound. Retrieved 11 June 2014. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB913591261156420500

- ↑ Kidscreen, 1 March 1999. New Euro hero available for hire. Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://kidscreen.com/1999/03/01/24620-19990301/

- ↑ Designweek, Angus Montgomery, 29 May 2014. Is it time to rebrand the EU? Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://www.designweek.co.uk/analysis/is-it-time-to-rebrand-the-eu/3038521.article

- ↑ CNBC, Alice Tidey, 19 May 2014. The EU's main problem? Its brand! Retrieved 11 June 2014. https://www.cnbc.com/id/101667358

- ↑ "European Olympic Team". Archived from the original on 31 March 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2006.

- ↑ Cendrowicz, Leo (1 March 2007). "United in Europe" (PDF). European Voice: 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "Olympics: Prodi wants to see EU flag next to national flags". EurActiv. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Eurobarometer 251, p 45, .