Scythians

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Russia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Scythians (/ˈsɪθiən,

The relationships between the peoples living in these widely separated regions remains unclear, and the term is used in both a broad and narrow sense. The term "Scythian" is used by modern scholars in an archaeological context for finds perceived to display attributes of the wider "Scytho-Siberian" culture, usually without implying an ethnic or linguistic connotation.[6] The term Scythic may also be used in a similar way,[7] "to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques".[8] Their westernmost territories during the Iron Age were known to classical Greek sources as Scythia, and in the more narrow sense "Scythian" is restricted to these areas, where the Scythian languages were spoken. Different definitions of "Scythian" have been used, leading to a good deal of confusion.[9]

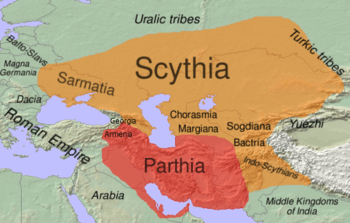

The Scythians were among the earliest peoples to master mounted warfare.[10] They kept herds of horses, cattle and sheep, lived in tent-covered wagons and fought with bows and arrows on horseback. They developed a rich culture characterised by opulent tombs, fine metalwork and a brilliant art style.[11] In the 8th century BC, they possibly raided Zhou China.[12] Soon after, they expanded westwards and dislodged the Cimmerians from power on the Pontic Steppe.[13] At their peak, Scythians came to dominate the entire steppe zone,[14][15] stretching from the Carpathian Mountains in the west to central China (Ordos culture) and the south Siberia (Tagar culture) in the east,[6][16] creating what has been called the first Central Asian nomadic empire, although there was little that could be called an organised state.[13][17]

Based in what is modern-day Ukraine, Southern European Russia and Crimea, the western Scythians were ruled by a wealthy class known as the Royal Scyths. The Scythians established and controlled the Silk Road, a vast trade network connecting Greece, Persia, India and China, perhaps contributing to the contemporary flourishing of those civilisations.[18] Settled metalworkers made portable decorative objects for the Scythians. These objects survive mainly in metal, forming a distinctive Scythian art.[19] In the 7th century BC, the Scythians crossed the Caucasus and frequently raided the Middle East along with the Cimmerians, playing an important role in the political developments of the region.[13] Around 650–630 BC, Scythians briefly dominated the Medes of the western Iranian Plateau,[20][21] stretching their power to the borders of Egypt.[10] After losing control over Media, the Scythians continued intervening in Middle Eastern affairs, playing a leading role in the destruction of the Assyrian Empire in the Sack of Nineveh in 612 BC. The Scythians subsequently engaged in frequent conflicts with the Achaemenid Empire. The western Scythians suffered a major defeat against Macedonia in the 4th century BC[10] and were subsequently gradually conquered by the Sarmatians, a related Iranian people from Central Asia.[22] The Eastern Scythians of the Asian Steppe (Saka) were attacked by the Yuezhi, Wusun and Xiongnu in the 2nd century BC, prompting many of them to migrate into South Asia,[23][24] where they became known as Indo-Scythians.[25] At some point, perhaps as late as the 3rd century AD after the demise of the Han dynasty and the Xiongnu, Eastern Scythians crossed the Pamir Mountains and settled in the western Tarim Basin, where the Scythian Khotanese and Tumshuqese languages are attested in Brahmi scripture from the 10th and 11th centuries AD.[24] The Kingdom of Khotan, at least partly Saka, was then conquered by the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which led to the Islamisation and Turkification of Northwest China. In Eastern Europe, by the early Medieval Ages, the Scythians and their closely related Sarmatians were eventually assimilated and absorbed (e.g. Slavicisation) by the Proto-Slavic population of the region.[26][27][28][29]

Names and terminology

In the strict sense 'Scythian' refers to the nomads north of the Black Sea and is distinguished from the very similar Sarmatians who lived north of the Caspian and later replaced the Scythians proper. The Persian term Saka is used for the Scythians in Central Asia. The Chinese used the term Sai (Chinese: 塞; Old Chinese: *sˤək), for Sakas who once inhabited the valleys of the Ili River and Chu River and moved into the Tarim Basin. Herodotus said the Scythians called themselves Skolotoi.[30]

Iskuzai or Askuzai is an Assyrian term for raiders south of the Caucasus who were probably Scythian. A group of Scythians/Sakas went south and gave their name to Sakastan. They, or a related group, invaded northern India and became the Indo-Scythians. Near the end of this article is a list of peoples that have been called Scythians.

Oswald Szemerényi studied the various words for Scythian and gave the following.[31] Most descend from the Indo-European root *skeud-, meaning "propel, shoot" (cognate with English shoot). *skud- is the zero-grade form of the same root.

The restored Scythian name is *skuda (roughly "archer"). This yields the ancient Greek Skuthēs (plural Skuthai Σκύθαι) and Assyrian Aškuz; Old Armenian: սկիւթ skiwtʰ is from itacistic Greek. A late Scythian sound change from /d/ to /l/ gives the Greek word Skolotoi (Σκώλοτοι, Herodotus 4.6), from Scythian *skula which, according to Herodotus, was the self-designation of the Royal Scythians. Other sound changes gave Sogdia. The form reflected in Old Persian: Sakā, Greek: Σάκαι; Latin: Sacae, Sanskrit: शक Śaka comes from an Iranian verbal root sak-, "go, roam" and thus means "nomad".[32]

In the broadest sense and in archaeology Scythian and Scythic can be used for all of the steppe nomads at the beginning of recorded history.[33] The grasslands of Mongolia and north China are often excluded, but the Ordos culture and Tagar culture seem to have had significant 'Scythian' features. More commonly 'Scythian' is restricted to the nomads of the western and central steppe who spoke Scythian languages of the Iranian family. If other languages were used in the region we have no definite evidence.

Origins

Literary evidence

The Scythians first appeared in the historical record in the 8th century BC.[34] Herodotus reported three contradictory versions as to the origins of the Scythians, but placed greatest faith in this version:[35]

There is also another different story, now to be related, in which I am more inclined to put faith than in any other. It is that the wandering Scythians once dwelt in Asia, and there warred with the Massagetae, but with ill success; they therefore quitted their homes, crossed the Araxes, and entered the land of Cimmeria.

Accounts by Herodotus of Scythian origins has been discounted recently; although his accounts of Scythian raiding activities contemporary to his writings have been deemed more reliable.[36] Moreover, the term Scythian, like Cimmerian, was used to refer to a variety of groups from the Black Sea to southern Siberia and central Asia. "They were not a specific people", but rather variety of peoples "referred to at variety of times in history, and in several places, none of which was their original homeland."[37] The New Testament includes a single reference to Scythians in Colossians 3:11, immediately after mentioning barbarians, possibly as an extreme example of a barbarian.[38]

Archaeology

.png)

Modern interpretation of historical, archaeological and anthropological evidence has proposed two broad hypotheses.[39] The first, formerly more espoused by Soviet and then Russian researchers, roughly followed Herodotus' (third) account, holding that the Scythians were an Eastern Iranian group who arrived from Inner Asia, i.e. from the area of Turkestan and western Siberia. [39][40]

The second hypothesis, according to Ghirshman and others, proposes that the Scythian cultural complex emerged from local groups of the "Timber Grave" (or Srubna) culture at the Black Sea coast,[39] although this is also associated with the Cimmerians. According to Dolukhanov this proposal is supported by anthropological evidence which has found that Scythian skulls are similar to preceding findings from the Timber Grave culture, and distinct from those of the Central Asian Sacae.[41] Yet, according to Mallory the archaeological evidence is poor, and the Andronovo culture and "at least the eastern outliers of the Timber-grave culture" may be identified as Indo-Iranian.[39]

Others have further stressed that "Scythian" was a very broad term used by both ancient and modern scholars to describe a whole host of otherwise unrelated peoples sharing only certain similarities in lifestyle (nomadism), cultural practices and language. The 1st millennium BC ushered a period of unprecedented cultural and economic connectivity amongst disparate and wide-ranging communities. A mobile, broadly similar lifestyle would have facilitated contacts amongst disparate ethnic groupings along the expansive Eurasian steppe from the Danube to Manchuria, leading to many cultural similarities. From the viewpoint of Greek and Persian ancient observers, they were all lumped together under the etic category "Scythians".

History

Classical Antiquity (600 BC to AD 300)

Herodotus provides the first detailed description of the Scythians. He classes the Cimmerians as a distinct autochthonous tribe, expelled by the Scythians from the northern Black Sea coast (Hist. 4.11–12). Herodotus also states (4.6) that the Scythians consisted of the Auchatae, Catiaroi, Traspians, and Paralatae or "Royal Scythians".

For Herodotus, the Scythians were outlandish barbarians living north of the Black Sea in what are now Moldova, Ukraine and Crimea.

— Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars from the Third Century to Alaric, pg. 14

In 512 BC, when King Darius the Great of Persia attacked the Scythians, he allegedly penetrated into their land after crossing the Danube. Herodotus relates that the nomadic Scythians frustrated the Persian army by letting it march through the entire country without an engagement.[42] According to Herodotus, Darius in this manner came as far as the Volga River.

During the 5th to 3rd centuries BC, the Scythians evidently prospered. When Herodotus wrote his Histories in the 5th century BC, Greeks distinguished Scythia Minor, in present-day Romania and Bulgaria, from a Greater Scythia that extended eastwards for a 20-day ride from the Danube River, across the steppes of today's East Ukraine to the lower Don basin. The Don, then known as Tanaïs, has served as a major trading route ever since. The Scythians apparently obtained their wealth from their control over the slave trade from the north to Greece through the Greek Black Sea colonial ports of Olbia, Chersonesos, Cimmerian Bosporus, and Gorgippia. They also grew grain, and shipped wheat, flocks, and cheese to Greece.

Strabo (c. 63 BC – AD 24) reports that King Ateas united under his power the Scythian tribes living between the Maeotian marshes and the Danube. His westward expansion brought him into conflict with Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 BC), who took military action against the Scythians in 339 BC. Ateas died in battle, and his empire disintegrated. In the aftermath of this defeat, the Celts seem to have displaced the Scythians from the Balkans; while in south Russia, a kindred tribe, the Sarmatians, gradually overwhelmed them. In 329 BC Philip's son, Alexander the Great, came into conflict with the Scythians at the Battle of Jaxartes. A Scythian army sought to take revenge against the Macedonians for the death of Ateas, as they pushed the borders of their empire north and east, and to take advantage of a revolt by the local Sogdian satrap. However, the Scythian army was defeated by Alexander at the Battle of Jaxartes. Alexander did not intend to subdue the nomads: he wanted to go to the south, where a far more serious crisis demanded his attention. He could do so now without loss of face; and in order to make the outcome acceptable to the Saccae, he released the Scythian prisoners of war without ransom in order to broker a peace agreement. This policy was successful, and the Scythians no longer harassed Alexander's empire. By the time of Strabo's account (the first decades AD), the Crimean Scythians had created a new kingdom extending from the lower Dnieper to the Crimea. The kings Skilurus and Palakus waged wars with Mithridates the Great (reigned 120–63 BC) for control of the Crimean littoral, including Chersonesos Taurica and the Cimmerian Bosporus. Their capital city, Scythian Neapolis, stood on the outskirts of modern Simferopol. The Goths destroyed it later, in the mid-3rd century AD.

Sakas of the Eastern Steppe

Modern scholars usually use the term Saka to refer to Iranian-speaking tribes who inhabited the Eastern Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[43][44] Ancient Persian inscriptions also used Saka to refer to western Scythians to the north of the Black Sea – the Sakā paradraya or "Saka beyond the sea".[45][46]

In the Achaemenid-era Old Persian inscriptions found at Persepolis, dated to the reign of Darius I (r. 522–486 BC), the Saka are said to have lived just beyond the borders of Sogdiana.[47][48] The term Sakā para Sugdam or "Saka beyond Sugda (Sogdiana)" was used by Darius to describe the people who formed the limits of his empire at the opposite end to Kush (the Ethiopians) in the west, i.e. at the eastern edge of his empire.[45][49] An inscription dated to the reign of Xerxes I (r. 486–465 BC) has them coupled with the Dahae people of Central Asia.[47] Two Saka tribes named in the Behistun Inscription, Sakā tigraxaudā ("Saka with pointy hats/caps") and the Sakā haumavargā ("haoma-drinking saka"), may be located to the east of the Caspian Sea.[45][50][51] Some argued that the Sakā haumavargā may be the Sakā para Sugdam, therefore Sakā haumavargā would be located further east than the Sakā tigraxaudā. Some argued for the Pamirs or Xinjiang as their location, although Jaxartes is considered to be their more likely location given that the name says "beyond Sogdiana" rather than Bactria.[45]

Cyrus the Great of the Persian Achaemenid Empire fought the Saka whose women were said to fight alongside their men.[52] According to Herodotus, Cyrus the Great also confronted the Massagetae, a people thought to be related to the Saka,[53] while campaigning to the east of the Caspian Sea and was killed in the battle in 530 BC.[54] Darius the Great also waged wars against the eastern Sakas, who fought him with three armies led by three kings according to Polyaenus.[55] In 520–519 BC, Darius I defeated the Sakā tigraxaudā tribe and captured their king Skunkha (depicted as wearing a pointed hat in the Behistun inscription).[43] The territories of Saka were absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire as part of Chorasmia that included much of Amu Darya (Oxus) and Syr Darya (Jaxartes),[56] and the Saka then supplied the Persian army with large number of mounted bowmen in the Achaemenid wars.[46]

In the Chinese Book of Han, the valleys of the Ili River and Chu River were called the "land of the Sai", i.e. the Saka. The exact date of their arrival in this region of Central Asia is unclear, perhaps it was just before the reign of Darius I.[57] Around 30 Saka tombs in the form of kurgans (burial mounds) have also been found in the Tian Shan area dated to between 550–250 BC. Indications of Saka presence have also been found in the Tarim Basin region, possibly as early as the 7th century BC.[58] Some modern scholars thought that the sacking of the Western Zhou capital Haojing in 770 BC might have been connected to a Scythian raid from the Altai before their westward expansion.[59]

However, as a consequence of the fight for supremacy between the Xiongnu and other groups, the Saka were pushed towards Bactria, and later on southward to northwest India and eastward to the oasis city-states of western Tarim Basin region of Xinjiang in Northwest China.[60][61]

Accounts of the migration of the Sakas are given in Chinese texts such as Sima Qian's Shiji. The Indo-European Yuezhi, who originally lived between Dunhuang and the Qilian Mountains of Gansu, China, were assaulted and forced to flee from the Hexi Corridor of Gansu by the Mongolic forces of the Xiongnu ruler Modu Chanyu, who conquered the area in 177–176 BC.[62][63][64] In turn the Yuezhi were responsible for attacking and pushing the Sai (i.e. Saka) southwest into Sogdiana, where in the mid 2nd century BC the latter crossed the Syr Darya into Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, but also into the Fergana Valley where they settled in Dayuan.[65][66] The ancient Greco-Roman geographer Strabo claims that the four tribes of the Asii, who took down the Bactrians in the Greek and Roman account, came from land north of Syr Darya where the Ili and Chu valleys are located.[57] The Saka then migrated down to the northwest area of the Indian subcontinent where they became known as Indo-Scythians, as well as eastward to the settlements of the Tarim Basin in present-day China such as Khotan and Tumshaq.

Khotan and kingdoms of the Tarim Basin

The Saka migrated from Bactria where they eventually settled in some of the oasis city-states of the Tarim Basin that at times fell under the influence of the Chinese Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD).[57] These states in the Tarim Basin include Khotan, Kashgar, Shache (莎車, probably named after the Saka inhabitants), Yanqi (焉耆, Karasahr) and Qiuci (龜茲, Kucha).[67][68]

The official administrative language of Khotan and nearby Shanshan was Gandhari Prakrit in the Kharosthi script.[69] There are however indications that Sakas were linked to the ruling elite – 3rd-century documents from Shanshan record the title of the king of Khotan as hinajha (i.e. "generalissimo"), an Iranian-based word equivalent to the Sanskrit title senapati, yet nearly identical to the Khotanese Saka hīnāysa attested in later documents.[69] The regnal periods were also given in Khotanese as kṣuṇa, "implies an established connection between the Iranian inhabitants and the royal power," according to the late Professor of Iranian Studies Ronald E. Emmerick (d. 2001).[69] He contended that Khotanese-Saka-language royal rescripts of Khotan dated to the 10th century "makes it likely that the ruler of Khotan was a speaker of Iranian."[69] Furthermore, he argued that the oldest form of the name of Khotan, hvatana, may be linked semantically with the name Saka.[70]

During China's Tang dynasty (618–907 AD), the region once again came under Chinese suzerainty with the campaigns of conquest by Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649).[71] From the late 8th to 9th centuries, the region changed hands between the Chinese Tang Empire and the rival Tibetan Empire.[72][73] The kingdom existed until it was conquered by the Muslim Turkic peoples of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which led to both the Turkification and Islamisation of the region.[74][75]

Indo-Scythians

After the Saka migrated into northwest area of the Indian subcontinent, the region became known as "land of the Saka" (i.e. Drangiana, of modern Afghanistan and Pakistan).[47] This is attested in a contemporary Kharosthi inscription found on the Mathura lion capital belonging to the Saka kingdom of the Indo-Scythians (200 BC – 400 AD) in northern India,[76] roughly the same time the Chinese record that the Saka had invaded and settled the country of Jibin 罽賓 (i.e. Kashmir, of modern-day India and Pakistan).[77] In the Persian language of contemporary Iran the territory of Drangiana was called Sakastāna, in Armenian as Sakastan, with similar equivalents in Pahlavi, Greek, Sogdian, Syriac, Arabic, and the Middle Persian tongue used in Turfan, Xinjiang, China.[76]

Late Antiquity

In Late Antiquity, the notion of a Scythian ethnicity grew more vague and outsiders might dub any people inhabiting the Pontic-Caspian steppe as "Scythians", regardless of their language. Thus, Priscus, a Byzantine emissary to Attila, repeatedly referred to the latter's followers as "Scythians". But Eunapius, Claudius Cladianus and Olympiodorus usually mean "Goths" when they write "Scythians".

The Goths had displaced the Sarmatians in the 2nd century from most areas near the Roman frontier, and by early medieval times, the Early Slavs (Proto-Slavs) marginalised Eastern Iranian dialects in Eastern Europe as they assimilated and absorbed the Iranian ethnic groups in the region.[26][27][28][29] The Turkic migration assimilated the Saka linguistically in Central Asia.

Although the classical Scythians may have largely disappeared by the 1st century BC, Eastern Romans continued to speak conventionally of "Scythians" to designate Germanic tribes and confederations[78] or mounted Eurasian nomadic barbarians in general: in AD 448 two mounted "Scythians" led the emissary Priscus to Attila's encampment in Pannonia. The Byzantines in this case carefully distinguished the Scythians from the Goths and Huns who also followed Attila.

The Sarmatians (including the Alans and finally the Ossetians) counted as Scythians in the broadest sense of the word – as speakers of Eastern Iranian languages,[79] and are considered mostly of Iranian descent.[80]

Byzantine sources also refer to the Rus raiders who attacked Constantinople circa 860 in contemporary accounts as "Tauroscythians", because of their geographical origin, and despite their lack of any ethnic relation to Scythians. Patriarch Photius may have first applied the term to them during the Siege of Constantinople (860).

Archaeology

Archaeological remains of the Scythians include kurgan tombs (ranging from simple exemplars to elaborate "Royal kurgans" containing the "Scythian triad" of weapons, horse-harness, and Scythian-style wild-animal art), gold, silk, and animal sacrifices, in places also with suspected human sacrifices.[81][82] Mummification techniques and permafrost have aided in the relative preservation of some remains. Scythian archaeology also examines the remains of North Pontic Scythian cities and fortifications.[83]

The spectacular Scythian grave-goods from Arzhan, and others in Tuva have been dated from about 900 BC onward. One grave find on the lower Volga gave a similar date, and one of the Steblev graves from the East European end of the Scythian area was dated to the late 8th century BC.[84]

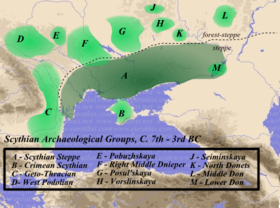

Archaeologists can distinguish three periods of ancient Scythian archaeological remains:

- 1st period – pre-Scythian and initial Scythian epoch: from the 9th to the middle of the 7th century BC

- 2nd period – early Scythian epoch: from the 7th to the 6th centuries BC

- 3rd period – classical Scythian epoch: from the 5th to the 4th centuries BC

From the 8th to the 2nd centuries BC, archaeology records a split into two distinct settlement areas: the older in the Sayan-Altai area in Central Asia, and the younger in the North Pontic area in Eastern Europe.[85]

An alternative scheme, relating to the "narrow" definition at the Western end of the steppe and into Europe, has:

- Early Scythian – from the mid-8th or the late 7th century BC to about 500 BC

- Classical Scythian or Mid-Scythian – from about 500 BC to about 300 BC

- Late Scythian – from about 200 BC to the early 2nd century CE, in the Crimea and the Lower Dnieper, by which time the population was settled.[86]

Kurgans

These large burial mounds (some over 20 metres high) provide the most valuable archaeological remains associated with the Scythians. They dot the Eurasian steppe belt, from Mongolia to Balkans, through Ukrainian and south Russian steppes, extending in great chains for many kilometers along ridges and watersheds. From them archaeologists have learned much about Scythian life and art.[87] Some Scythian tombs reveal traces of Greek, Chinese, and Indian craftsmanship, suggesting a process of Hellenisation, Sinification, and other local influences among the Scythians.[88]

The Ukrainian term for such a burial mound, kurhán (Ukrainian: Курган) as well as the Russian term kurgán, derives from a Turkic word for "castle".[89]

Some Scythian-Sarmatian cultures may have given rise to Greek stories of Amazons. Graves of armed females have been found in southern Ukraine and Russia. David Anthony notes, "About 20% of Scythian-Sarmatian 'warrior graves' on the lower Don and lower Volga contained females dressed for battle as if they were men, a style that may have inspired the Greek tales about the Amazons."[90]

Excavation at kurgan Sengileevskoe-2 found gold bowls with coatings indicating a strong opium beverage was used while cannabis was burning nearby. The gold bowls depicted scenes showing clothing and weapons.[91]

Pazyryk culture

Eastern Scythian burials documented by modern archaeologists include the kurgans at Pazyryk in the Ulagan (Red) district of the Altai Republic, south of Novosibirsk in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia (near Mongolia). Archaeologists have extrapolated the Pazyryk culture from these finds: five large burial mounds and several smaller ones between 1925 and 1949, one opened in 1947 by Russian archaeologist Sergei Rudenko. The burial mounds concealed chambers of larch-logs covered over with large cairns of boulders and stones.[93]

The Pazyryk culture flourished between the 7th and 3rd century BC in the area associated with the Sacae.

Ordinary Pazyryk graves contain only common utensils, but in one, among other treasures, archaeologists found the famous Pazyryk Carpet, the oldest surviving wool-pile oriental rug. Another striking find, a 3-metre-high four-wheel funerary chariot, survived well-preserved from the 5th to 4th century BC.[94]

Bilsk excavations

Recent digs (see:Gelonus) in a village Bilsk near Poltava (Ukraine) have uncovered a "vast city", with the largest area of any city in the world at that time (Bilsk settlement). It has been tentatively identified by a team of archaeologists led by Boris Shramko as the site of Gelonus, the purported capital of Scythia. The city's commanding ramparts and vast area of 40 square kilometers exceed even the outlandish size reported by Herodotus. Its location at the northern edge of the Ukrainian steppe would have allowed strategic control of the north-south trade-route. Judging by the finds dated to the 5th and 4th centuries BC, craft workshops and Greek pottery abounded.

Tillia Tepe treasure

A site found in 1968 in Tillia Tepe (literally "the golden hill") in northern Afghanistan (former Bactria) near Shebergan consisted of the graves of five women and one man with extremely rich jewelry, dated to around the 1st century BC, and probably related to that of Scythian tribes normally living slightly to the north. Altogether the graves yielded several thousands of pieces of fine jewelry, usually made from combinations of gold, turquoise and lapis-lazuli.

A high degree of cultural syncretism pervades the findings, however. Hellenistic cultural and artistic influences appear in many of the forms and human depictions (from amorini to rings with the depiction of Athena and her name inscribed in Greek), attributable to the existence of the Seleucid empire and Greco-Bactrian kingdom in the same area until around 140 BC, and the continued existence of the Indo-Greek kingdom in the northwestern Indian sub-continent until the beginning of our era. This testifies to the richness of cultural influences in the area of Bactria at that time.

Culture and society

Tribal divisions

Scythians lived in confederated tribes, a political form of voluntary association which regulated pastures and organised a common defence against encroaching neighbours for the pastoral tribes of mostly equestrian herdsmen. While the productivity of domesticated animal-breeding greatly exceeded that of the settled agricultural societies, the pastoral economy also needed supplemental agricultural produce, and stable nomadic confederations developed either symbiotic or forced alliances with sedentary peoples – in exchange for animal produce and military protection.

Herodotus relates that three main tribes of the Scythians descended from three brothers, Lipoxais, Arpoxais, and Colaxais:[95]

In their reign a plough, a yoke, an axe, and a bowl, all made of gold, fell from heaven upon the Scythian territory. The oldest of the brothers wished to take them away, but as he drew near the gold began to burn. The second brother approached them, but with the like result. The third and youngest then approached, upon which the fire went out, and he was enabled to carry away the golden gifts. The two eldest then made the youngest king, and henceforth the golden gifts were watched by the king with the greatest care, and annually approached with magnificent sacrifices.[96]

Herodotus also mentions a royal tribe or clan, an elite which dominated the other Scythians:

Then on the other side of the Gerros we have those parts which are called the "Royal" lands and those Scythians who are the bravest and most numerous and who esteem the other Scythians their slaves.[97]

The elder brothers then, acknowledging the significance of this thing, delivered the whole of the kingly power to the youngest. From Lixopais, they say, are descended those Scythians who are called the race of the Auchatai; from the middle brother Arpoxais those who are called Catiaroi and Traspians, and from the youngest of them the "Royal" tribe, who are called Paralatai: and the whole together are called, they say, Scolotoi, after the name of their king; but the Hellenes gave them the name of Scythians. Thus the Scythians say they were produced; and from the time of their origin, that is to say from the first king Targitaos, to the passing over of Dareios [the Persian Emperor Darius I] against them [512 BC], they say that there is a period of a thousand years and no more.[98]

The rich burials of Scythian kings in tumuli (often known by the Turkic name kurgan) is evidence for the existence of a powerful elite. While an elite clan is named in some classical sources as the "Royal Dahae", the Dahae proper are generally regarded as an extinct Indo-European people, who occupied what is now Turkmenistan, and were distinct from the Scythians.

Although scholars have traditionally treated the three tribes as geographically distinct, Georges Dumézil interpreted the divine gifts as the symbols of social occupations, illustrating his trifunctional vision of early Indo-European societies: the plough and yoke symbolised the farmers, the axe – the warriors, the bowl – the priests.[99] According to Dumézil, "the fruitless attempts of Arpoxais and Lipoxais, in contrast to the success of Colaxais, may explain why the highest strata was not that of farmers or magicians, but rather that of warriors."[100]

Warfare

A warlike people, the Scythians were particularly known for their equestrian skills, and their early use of composite bows shot from horseback. With great mobility, the Scythians could absorb the attacks of more cumbersome footsoldiers and cavalry, just retreating into the steppes. Such tactics wore down their enemies, making them easier to defeat. The Scythians were notoriously aggressive warriors. They "fought to live and lived to fight" and "drank the blood of their enemies and used the scalps as napkins."[92][101] Ruled by small numbers of closely allied elites, Scythians had a reputation for their archers, and many gained employment as mercenaries. Scythian elites had kurgan tombs: high barrows heaped over chamber-tombs of larch wood, a deciduous conifer that may have had special significance as a tree of life-renewal, for it stands bare in winter. Burials at Pazyryk in the Altay Mountains have included some spectacularly preserved Scythians of the "Pazyryk culture" – including the Ice Maiden of the 5th century BC.

The Ziwiye hoard, a treasure of gold and silver metalwork and ivory found near the town of Sakiz south of Lake Urmia and dated to between 680 and 625 BC, includes objects with Scythian "animal style" features. One silver dish from this find bears some inscriptions, as yet undeciphered and so possibly representing a form of Scythian writing.

Scythians also had a reputation for the use of barbed and poisoned arrows of several types, for a nomadic life centered on horses – "fed from horse-blood" according to Herodotus – and for skill in guerrilla warfare.

Clothing

According to Herodotus, Scythian costume consisted of padded and quilted leather trousers tucked into boots, and open tunics. They rode without stirrups or saddles, using only saddle-cloths. Herodotus reports that Scythians used cannabis, both to weave their clothing and to cleanse themselves in its smoke (Hist. 4.73–75); archaeology has confirmed the use of cannabis in funerary rituals.

Scythian women dressed in much the same fashion as men. A Pazyryk burial, discovered in the 1990s, contained the skeletons of a man and a woman, each with weapons, arrowheads, and an axe. Herodotus mentioned that Sakas had "high caps and … wore trousers." Clothing was sewn from plain-weave wool, hemp cloth, silk fabrics, felt, leather and hides.

Pazyryk findings give the most number of almost fully preserved garments and clothing worn by the Scythian/Saka peoples. Ancient Persian bas-reliefs, inscriptions from Apadana and Behistun, ancient Greek pottery, archaeological findings from Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, China et al. give visual representations of these garments.

Herodotus says Sakas had "high caps tapering to a point and stiffly upright." Asian Saka headgear is clearly visible on the Persepolis Apadana staircase bas-relief – high pointed hat with flaps over ears and the nape of the neck.[102] From China to the Danube delta, men seemed to have worn a variety of soft headgear – either conical like the one described by Herodotus, or rounder, more like a Phrygian cap.

Women wore a variety of different headdresses, some conical in shape others more like flattened cylinders, also adorned with metal (golden) plaques.

Based on the Pazyryk findings (can be seen also in the south Siberian, Uralic and Kazakhstan rock drawings) some caps were topped with zoomorphic wooden sculptures firmly attached to a cap and forming an integral part of the headgear, similar to the surviving nomad helmets from northern China. Men and warrior women wore tunics, often embroidered, adorned with felt applique work, or metal (golden) plaques.

Persepolis Apadana again serves a good starting point to observe tunics of the Sakas. They appear to be a sewn, long sleeve garment that extended to the knees and belted with a belt while owner's weapons were fastened to the belt (sword or dagger, gorytos, battleax, whetstone etc.). Based on numerous archeological findings in Ukraine, southern Russian and Kazakhstan men and warrior women wore long sleeve tunics that were always belted, often with richly ornamented belts. The Kazakhstan Saka (e.g. Issyk Golden Man/Maiden) wore shorter tunics and more close fitting tunics than the Pontic steppe Scythians. Some Pazyryk culture Saka wore short belted tunic with a lapel on a right side, upright collar, 'puffed' sleeves narrowing at a wrist and bound in narrow cuffs of a color different from the rest of the tunic.

Scythian women wore long, loose robes, ornamented with metal plaques (gold). Women wore shawls, often richly decorated with metal (golden) plaques.

Men and women wore coats, e.g. Pazyryk Saka had many varieties, from fur to felt. They could have worn a riding coat that later was known as a Median robe or Kantus. Long sleeved, and open, it seems that on the Persepolis Apadana Skudrian delegation is perhaps shown wearing such coat. The Pazyryk felt tapestry shows a rider wearing a billowing cloak.

Men and women wore long trousers, often adorned with metal plaques and often embroidered or adorned with felt appliqués; trousers could have been wider or tight fitting depending on the area. Materials used depended on the wealth, climate and necessity.

Men and women warriors wore variations of long and shorter boots, wool-leather-felt gaiter-boots and moccasin-like shoes. They were either of a laced or simple slip on type. Women wore also soft shoes with metal (gold) plaques.

Men and women wore belts. Warrior belts were made of leather, often with gold or other metal adornments and had many attached leather thongs for fastening of the owner's gorytos, sword, whet stone, whip etc. Belts were fastened with metal or horn belt-hooks, leather thongs and metal (often golden) or horn belt-plates.

Art

Scythian contacts with craftsmen in Greek colonies along the northern shores of the Black Sea resulted in the famous Scythian gold adornments that feature among the most glamorous artifacts of world museums. Ethnographically extremely useful as well, the gold depicts Scythian men as bearded, long-haired Caucasoids. "Greco-Scythian" works depicting Scythians within a much more Hellenic style date from a later period, when Scythians had already adopted elements of Greek culture, and the most elaborate royal pieces are assumed to have been made by Greek goldsmiths for this lucrative market. Other metalwork pieces from across the whole Eurasian steppe use an animal style, showing animals, often in combat and often with their legs folded beneath them. This origins of this style remain debated, but it probably both received and gave influences in the art of the neighbouring settled peoples, and acted as a fast route for transmission of motifs across the width of Eurasia.

Surviving Scythian objects are mostly small portable pieces of metalwork: elaborate personal jewelry, weapon-ornaments and horse-trappings. But finds from sites with permafrost show rich and brightly coloured textiles, leatherwork and woodwork, not to mention tattooing. The western royal pieces executed Central-Asian animal motifs with Greek realism: winged gryphons attacking horses, battling stags, deer, and eagles, combined with everyday motifs like milking ewes.

In 2000, the touring exhibition 'Scythian Gold' introduced the North American public to the objects made for Scythian nomads by Greek craftsmen north of the Black Sea, and buried with their Scythian owners under burial mounds on the flat plains of present-day Ukraine. In 2001, the discovery of an undisturbed royal Scythian burial-barrow illustrated Scythian animal-style gold that lacks the direct influence of Greek styles. Forty-four pounds of gold weighed down the royal couple in this burial, discovered near Kyzyl, capital of the Siberian republic of Tuva.

Ancient influences from Central Asia became identifiable in China following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western and northwestern border territories from the 8th century BC. The Chinese adopted the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat), particularly the rectangular belt-plaques made of gold or bronze, and created their own versions in jade and steatite.[103]

Following their expulsion by the Yuezhi, some Scythians may also have migrated to the area of Yunnan in southern China. Scythian warriors could also have served as mercenaries for the various kingdoms of ancient China. Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian civilisation of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.[104]

Scythian influences have been identified as far as Korea and Japan. Various Korean artifacts, such as the royal crowns of the kingdom of Silla, are said to be of Scythian design.[105] Similar crowns, brought through contacts with the continent, can also be found in Kofun era Japan.[106]

Religion

The religious beliefs of the Scythians was a type of Pre-Zoroastrian Iranian religion and differed from the post-Zoroastrian Iranian thoughts.[107] Foremost in the Scythian pantheon stood Tabiti, who was later replaced by Atar, the fire-pantheon of Iranian tribes, and Agni, the fire deity of Indo-Aryans.[107] The Scythian belief was a more archaic stage than the Zoroastrian and Hindu systems. The use of cannabis to induce trance and divination by soothsayers was a characteristic of the Scythian belief system.[107] A class of priests, the Enarei, worshipped the goddess Argimpasa and assumed feminine identities.

Language

The Scythian group of languages in the early period are essentially unattested, and their internal divergence is difficult to judge. They belonged to the Eastern Iranian family of languages. Whether all the peoples included in the "Scytho-Siberian" archaeological culture spoke languages from this family is uncertain.

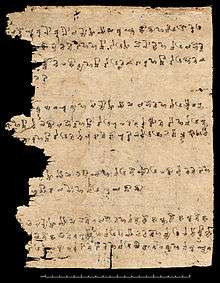

The Scythian languages may have formed a dialect continuum: "Scytho-Sarmatian" in the west and "Scytho-Khotanese" or Saka in the east.[108] Modern scholarly consensus is that the Saka language, ancestor to the Pamir languages in northern India and Khotanese in Xinjiang, China belongs to the Scythian languages.[109] The Scythian languages were mostly marginalised and assimilated as a consequence of the late antiquity and early Middle Ages Slavic and Turkic expansion. Some remnants of the eastern groups have survived as modern Pashto and Pamiri languages in Central Asia. The western (Sarmatian) group of ancient Scythian survived as the medieval language of the Alans and eventually gave rise to the modern Ossetian language.[110]

Evidence of the Middle Iranian "Scytho-Khotanese" language survives in Northwest China, where Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist literature, have been found primarily in Khotan and Tumshuq (northeast of Kashgar).[111] They largely predate the arrival of Islam to the region under the Turkic Kara-Khanids.[111] Similar documents in the Khotanese-Saka language were found in Dunhuang and date mostly from the 10th century.[112]

Physical appearance

Early physical analyses have unanimously concluded that the Scythians, even those in the east (e.g. the Pazyryk region), possessed predominantly "Europid" features, although mixed 'Euro-mongoloid" phenotypes also occur, depending on site and period.[113]

In artworks, the Scythians are portrayed exhibiting European traits.[114] In Histories, the 5th-century Greek historian Herodotus describes the Budini of Scythia as red-haired and grey-eyed.[114] In the 5th century BC, Greek physician Hippocrates argued that the Scythians have purron (ruddy) skin.[114][115] In the 3rd century BC, the Greek poet Callimachus described the Arismapes (Arimaspi) of Scythia as fair-haired.[114][116] The 2nd century BC Han Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described the Sai (Saka) as having yellow (probably meaning hazel or green), and blue eyes.[114] In Natural History, the 1st century AD Roman author Pliny the Elder characterises the Seres, sometimes identified as Iranians or Tocharians, as red-haired and blue-eyed.[114][117] In the late 2nd century AD, the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria says that the Scythians were fair-haired.[114][118] The 2nd century Greek philosopher Polemon includes the Scythians among the northern peoples characterised by red hair and blue-grey eyes.[114] In the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, the Greek physician Galen declares that Sarmatians, Scythians and other northern peoples have reddish hair.[114][119] The fourth-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that the Alans, a people closely related to the Scythians, were tall, blond and light-eyed.[120] The 4th century bishop of Nyssa Gregory of Nyssa wrote that the Scythians were fair skinned and blond haired.[121] The 5th-century physician Adamantius, who often follow Polemon, describes the Scythians are fair-haired.[114][122] It is possible that the later physical descriptions by Adamantius and Gregory of Scythians refer to East Germanic tribes, as the latter were frequently referred to as "Scythians" in Roman sources at that time.

Historiography

Herodotus

Herodotus wrote about an enormous city, Gelonus, in the northern part of Scythia,[123] perhaps a site near modern Bilsk, Kotelva Raion, Ukraine:

- The Budini are a large and powerful nation: they have all deep blue eyes, and bright red hair. There is a city in their territory, called Gelonus, which is surrounded with a lofty wall, thirty furlongs (τριήκοντα σταδίων = c. 5.5 km) each way, built entirely of wood. All the houses in the place and all the temples are of the same material. Here are temples built in honour of the Grecian gods, and adorned after the Greek fashion with images, altars, and shrines, all in wood. There is even a festival, held every third year in honour of Bacchus, at which the natives fall into the Bacchic fury. For the fact is that the Geloni were anciently Greeks, who, being driven out of the factories along the coast, fled to the Budini and took up their abode with them. They still speak a language half Greek, half Scythian.

Herodotus and other classical historians listed quite a number of tribes who lived near the Scythians, and presumably shared the same general milieu and nomadic steppe culture, often called "Scythian culture", even though scholars may have difficulties in determining their exact relationship to the "linguistic Scythians". A partial list of these tribes includes the Agathyrsi, Geloni, Budini, and Neuri.

Herodotus presented four different versions of Scythian origins:

- Firstly (4.7), the Scythians' legend about themselves, which portrays the first Scythian king, Targitaus, as the child of the sky-god and of a daughter of the Dnieper. Targitaus allegedly lived a thousand years before the failed Persian invasion of Scythia, or around 1500 BC. He had three sons, before whom fell from the sky a set of four golden implements – a plough, a yoke, a cup and a battle-axe. Only the youngest son succeeded in touching the golden implements without them bursting with fire, and this son's descendants, called by Herodotus the "Royal Scythians", continued to guard them.

- Secondly (4.8), a legend told by the Pontic Greeks featuring Scythes, the first king of the Scythians, as a child of Hercules and Echidna.

- Thirdly (4.11), in the version which Herodotus said he believed most, the Scythians came from a more southern part of Central Asia, until a war with the Massagetae (a powerful tribe of steppe nomads who lived just northeast of Persia) forced them westward.

- Finally (4.13), a legend which Herodotus attributed to the Greek bard Aristeas, who claimed to have got himself into such a Bachanalian fury that he ran all the way northeast across Scythia and further. According to this, the Scythians originally lived south of the Rhipaean mountains, until they got into a conflict with a tribe called the Issedones, pressed in their turn by the Cyclopes; and so the Scythians decided to migrate westwards.

Persians and other peoples in Asia referred to the Scythians living in Asia as Sakas. Herodotus (IV.64) describes them as Scythians, although they figure under a different name:

The Sacae, or Scyths, were clad in trousers, and had on their heads tall stiff caps rising to a point. They bore the bow of their country and the dagger; besides which they carried the battle-axe, or sagaris. They were in truth Amyrgian (Western) Scythians, but the Persians called them Sacae, since that is the name which they gave to all Scythians.

Strabo

In the 1st century BC, the Greek-Roman geographer Strabo gave an extensive description of the eastern Scythians, whom he located in Central Asia beyond Bactria and Sogdiana.[124]

Strabo went on to list the names of the various tribes he believed to be "Scythian",[124] and in so doing almost certainly conflated them with unrelated tribes of eastern Central Asia.

Now the greater part of the Scythians, beginning at the Caspian Sea, are called Däae, but those who are situated more to the east than these are named Massagetae and Sacae, whereas all the rest are given the general name of Scythians, though each people is given a separate name of its own. They are all for the most part nomads. But the best known of the nomads are those who took away Bactriana from the Greeks, I mean the Asii, Pasiani, Tochari, and Sacarauli, who originally came from the country on the other side of the Iaxartes River that adjoins that of the Sacae and the Sogdiani and was occupied by the Sacae. And as for the Däae, some of them are called Aparni, some Xanthii, and some Pissuri. Now of these the Aparni are situated closest to Hyrcania and the part of the sea that borders on it, but the remainder extend even as far as the country that stretches parallel to Aria.

Between them and Hyrcania and Parthia and extending as far as the Arians is a great waterless desert, which they traversed by long marches and then overran Hyrcania, Nesaea, and the plains of the Parthians. And these people agreed to pay tribute, and the tribute was to allow the invaders at certain appointed times to overrun the country and carry off booty. But when the invaders overran their country more than the agreement allowed, war ensued, and in turn their quarrels were composed and new wars were begun. Such is the life of the other nomads also, who are always attacking their neighbors and then in turn settling their differences.

- (Strabo, Geography, 11.8.1; transl. 1903 by H.C. Hamilton & W. Falconer.) [124]

Indian sources

Sakas receive numerous mentions in Indian texts, including the Puranas, the Manusmriti, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Mahabhashya of Patanjali.

Genetics

Numerous ancient mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) samples have now been recovered from remains in Bronze and Iron Age burials in the Eurasian steppe and Siberian forest zone, the putative "ancestors" of the historical Scythians. Compared to Y-DNA, mtDNA is easier to extract and amplify from ancient specimens due to numerous copies of mtDNA per cell.

The earliest studies could only analyze segments of mtDNA, thus providing only broad correlations of affinity to modern West Eurasian or East Eurasian populations. For example, in a 2002 study the mitochondrial DNA of Saka period male and female skeletal remains from a double inhumation kurgan at the Beral site in Kazakhstan was analysed. The two individuals were found to be not closely related. The HV1 mitochondrial sequence of the male was similar to the Anderson sequence which is most frequent in European populations. The HV1 sequence of the female suggested a greater likelihood of Asian origins.[125]

More recent studies have been able to type for specific mtDNA lineages. For example, a 2004 study examined the HV1 sequence obtained from a male "Scytho-Siberian" at the Kizil site in the Altai Republic. It belonged to the N1a maternal lineage, a geographically West Eurasian lineage.[126] Another study by the same team, again of mtDNA from two Scytho-Siberian skeletons found in the Altai Republic, showed that they had been typical males "of mixed Euro-Mongoloid origin". One of the individuals was found to carry the F2a maternal lineage, and the other the D lineage, both of which are characteristic of East Eurasian populations.[127]

These early studies have been elaborated by an increasing number of studies by Russian scholars. Conclusions are (i) an early, Bronze Age mixing of both west and east Eurasian lineages, with western lineages being found far to the east, but not vice versa; (ii) an apparent reversal by Iron Age times, with an increasing presence of East Eurasian lineages in the western steppe; (iii) the possible role of migrations from the south, the Balkano-Danubian and Iranian regions, toward the steppe.[128][129][130]

Ancient Y-DNA data was finally provided by Keyser et al in 2009. They studied the haplotypes and haplogroups of 26 ancient human specimens from the Krasnoyarsk area in Siberia dated from between the middle of the 2nd millennium BC and the 4th century AD (Scythian and Sarmatian timeframe). Nearly all subjects belonged to haplogroup R-M17. The authors suggest that their data shows that between the Bronze and the Iron Ages the constellation of populations known variously as Scythians, Andronovians, etc. were blue- (or green-) eyed, fair-skinned and light-haired people who might have played a role in the early development of the Tarim Basin civilisation. Moreover, this study found that they were genetically more closely related to modern populations in eastern Europe than those of central and southern Asia.[131] The ubiquity and dominance of the R1a Y-DNA lineage contrasted markedly with the diversity seen in the mtDNA profiles.

However, this comparison was made on the basis of what is now seen as an unsophisticated technique, short tandem repeats (STRs). Since the 2009 study by Keyser et al, population and geographic specific SNPs have been discovered which can accurately distinguish between "European" R1a (M458, Z280) and "South Asian" R1a (Z93)[132] Re-analyzing ancient Scytho-Siberian samples for these more specific subclades will clarify whether the Eurasian steppe populations had an ultimately Eastern European or EurAsian origin, or, perhaps, both. This, in turn, might also depend on which population is studied, i.e. Herodotus' European "classical" Scythians, the Central Asian Sakae, or un-named nomadic groups in the far east (Altai region) who also belong to the Scythian cultural tradition.

According to a 2017 study of mitochondrial lineages in Iron Age Black Sea Scythians, a comparison of North Pontic Region (NPR) Scythian mtDNA lineages with other ancient groups suggests close genetic affinities with representatives of the Bronze Age Srubnaya population, which is in agreement with the archaeological hypothesis suggesting the Srubnaya people as the ancestors of the NPR Scythians.[133]

Recently, new aDNA tests were made on various ancient samples across Eurasia, among them two from Scythian burials. This time the modern techniques of SNPs (in comparison to STRs in earlier tests) were used. The Iron Age Scythian samples from the Volga region and the European Steppes appear closely related to neither Eastern Europeans nor South and Central Asians. Based on the results both samples appear to be a link between the Iranic speaking people of South-Central Asia and both the people of the northern regions of West Asia and of Eastern Europeans. This fits with their geographic origin.[134][135][136]

Ancient genome-wide analysis on samples from the southern Ural region, East Kazakhstan and Tuva, shows that western and eastern Scythians arose independently in their respective geographic regions and during the 1st millennium BCE experienced significant population expansions with gene flow being asymmetrical from western to eastern groups, rather than the reverse. Iron Age Scythians can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya people, from the Russian Steppe, and East Asian populations, similar to the Han and the Nganasan (a Samoyedic people from northern Siberia). The East Asian admixture is pervasive across diverse present-day people from Siberia and Central Asia. Contemporary populations linked to western Iron Age Scythians can be found among diverse ethnic groups in the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia, spread across many Iranian and other Indo-European speaking groups. Populations with genetic similarities to eastern Scythian groups are found almost exclusively among Turkic language speakers, particularly from the Kipchak branch of Turkic languages. These results are consistent with gene flow across the steppe territory between Europe and East Asia.[134][137][138]

Legacy

Early Modern usage

Owing to their reputation as established by Greek historians, the Scythians long served as the epitome of savagery and barbarism.

In the New Testament, in a letter ascribed to Paul "Scythian" is used as an example of people whom some label pejoratively, but who are, in Christ, acceptable to God:

Here there is no Greek or Jew. There is no difference between those who are circumcised and those who are not. There is no rude outsider, or even a Scythian. There is no slave or free person. But Christ is everything. And he is in everything.[139]

Shakespeare, for instance, alluded to the legend that Scythians ate their children in his play King Lear:

The barbarous Scythian

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

¨ Be as well neighbour'd, pitied, and relieved,

As thou my sometime daughter.[140]

Characteristically, early modern English discourse on Ireland frequently resorted to comparisons with Scythians in order to confirm that the indigenous population of Ireland descended from these ancient "bogeymen", and showed themselves as barbaric as their alleged ancestors. Edmund Spenser wrote that

the Chiefest [nation that settled in Ireland] I Suppose to be Scithians ... which firste inhabitinge and afterwarde stretchinge themselves forthe into the lande as theire numbers increased named it all of themselues Scuttenlande which more brieflye is Called Scuttlande or Scotlande.[141]

As proofs for this origin Spenser cites the alleged Irish customs of blood-drinking, nomadic lifestyle, the wearing of mantles and certain haircuts and

Cryes allsoe vsed amongeste the Irishe which savor greatlye of the Scythyan Barbarisme.

William Camden, one of Spenser's main sources, comments on this legend of origin that

to derive descent from a Scythian stock, cannot be thought any waies dishonourable, seeing that the Scythians, as they are most ancient, so they have been the Conquerours of most Nations, themselves alwaies invincible, and never subject to the Empire of others.[142]

The 15th-century Polish chronicler Jan Długosz was the first to connect the prehistory of Poland with Sarmatians, and the connection was taken up by other historians and chroniclers, such as Marcin Bielski, Marcin Kromer and Maciej Miechowita. Other Europeans depended for their view of Polish Sarmatism on Miechowita's Tractatus de Duabus Sarmatiis, a work which provided a substantial source of information about the territories and peoples of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in a language of international currency.[143] Tradition specified that the Sarmatians themselves were descended from Japheth, son of Noah.[144]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, foreigners regarded the Russians as descendants of Scythians. It became conventional to refer to Russians as Scythians in 18th-century poetry, and Alexander Blok drew on this tradition sarcastically in his last major poem, The Scythians (1920). In the 19th century, romantic revisionists in the West transformed the "barbarian" Scyths of literature into the wild and free, hardy and democratic ancestors of all blond Indo-Europeans.

Descent claims

.jpg)

A number of groups have claimed possible descent from the Scythians, including the Ossetians, Pashtuns (in particular, the Sakzai tribe), Jat people[145] and the Parthians (whose homelands lay to the east of the Caspian Sea and who were thought to have come there from north of the Caspian). Some legends of the Poles,[143] the Picts, the Gaels, the Hungarians (in particular, the Jassics), among others, also include mention of Scythian origins. Some writers claim that Scythians figured in the formation of the empire of the Medes and likewise of Caucasian Albania.

The Scythians also feature in some national origin-legends of the Celts. In the second paragraph of the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, the élite of Scotland claim Scythia as a former homeland of the Scots. According to the 11th-century Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland), the 14th-century Auraicept na n-Éces and other Irish folklore, the Irish originated in Scythia and were descendants of Fénius Farsaid, a Scythian prince who created the Ogham alphabet and who was one of the principal architects of the Gaelic language.

The Carolingian kings of the Franks traced Merovingian ancestry to the Germanic tribe of the Sicambri. Gregory of Tours documents in his History of the Franks that when Clovis was baptised, he was referred to as a Sicamber with the words "Mitis depone colla, Sicamber, adora quod incendisti, incendi quod adorasti." The Chronicle of Fredegar in turn reveals that the Franks believed the Sicambri to be a tribe of Scythian or Cimmerian descent, who had changed their name to Franks in honour of their chieftain Franco in 11 BC.

Based on such accounts of Scythian founders of certain Germanic as well as Celtic tribes, British historiography in the British Empire period such as Sharon Turner in his History of the Anglo-Saxons, made them the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons.

The idea was taken up in the British Israelism of John Wilson, who adopted and promoted the idea that the "European Race, in particular the Anglo-Saxons, were descended from certain Scythian tribes, and these Scythian tribes (as many had previously stated from the Middle Ages onward) were in turn descended from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel."[146] Tudor Parfitt, author of The Lost Tribes of Israel and Professor of Modern Jewish Studies, points out that the proof cited by adherents of British Israelism is "of a feeble composition even by the low standards of the genre."[147]

Geneticist Eran Elhaik believes the word Ashkenaz (i.e. Ashkenazi Jews) is derived from the ancient Assyrian and Babylonian name for the Scythians. He places the original homeland of the Ashkenazi Jews in north-east Turkey and a region to the north of the Black sea.[148]

List of people and tribes called Scythians

- Agathyrsi

- Amardi

- Amyrgians

- Androphagi

- Dahae

- Hamaxobii

- Indo-Scythians

- Massagetae

- Orthocorybantians

- Saka

- Sindi

- Spali

- Tauri

- Thyssagetae

Related ancient peoples

See also

References

- ↑ Sinor (1990, p. 97)

- ↑ Bonfante (2011, p. 110)

- ↑ Sinor (1990, p. 97 Iranian-speaking tribes)

- ↑ West 2009, p. 713-717

- ↑ Drews (2004, pp. 86–90)

- 1 2 Davis-Kimball (1995, pp. 27–28)

- ↑ Watson, William, "The Chinese Contribution to Eastern Nomad Culture in the Pre-Han and Early Han Periods", World Archaeology, Vol. 4, No. 2, Nomads (Oct., 1972), pp. 139–149, Taylor & Francis, Ltd., JSTOR Archived 2017-03-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Di Cosimo, Nicola, "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China (1,500 – 221 BC)", in: M. Loeuwe, E.L. Shaughnessy, eds, The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221BC, 1999, Cambridge University Press 1999, ISBN 9780521470308, "Even though there were fundamental ways in which nomadic groups over such a vast territory differed, the terms “Scythian” and “Scythic” have been widely adopted to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques. Archaeologists have used the term “Scythic continuum” in a broad cultural sense to indicate the early nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppe. The term “Scythic” draws attention to the fact that there are elements – shapes of weapons, vessels, and ornaments, as well as lifestyle – common to both the eastern and the western ends of the Eurasian steppe region."

- ↑ Ivantchik, ii

- 1 2 3 "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ "Scythians". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2008.

- ↑ "The Steppe". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 "History of Central Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2014-05-05. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, p. 117 "The Scythians, or Northern Iranians, who were culturally and ethnolinguistically a single group at the beginning of their expansion, had earlier controlled the entire steppe zone."

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, pp. 377–380 "... conquest of the entire steppe zone by the Northern Iranians—literally, by the "Scythians"-in the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age"

- ↑ Bonfante (2011, p. 71)

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, p. 11

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, pp. 58–70

- ↑ "Scythian Art". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ "Ancient Iran: The Kingdom of the Medes". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, p. 49

- ↑ "Sarmatian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Benjamin, Craig (March 2003). "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia". Ērān ud Anērān Webfestschrift Marshak. Archived from the original on 2015-02-18. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- 1 2 "Chinese History – Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians". Chinaknowledge. Archived from the original on 2015-01-19. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, p. 85 "The Saka, or Śaka, people then began their long migration that ended with their conquest of northern India, where they are also known as the Indo-Scythians."

- 1 2 Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians, 600 BC-AD 450. Osprey Publishing. p. 39.

(..) Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations.

- 1 2 Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 523.

(..) In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations.

- 1 2 Atkinson, Dorothy; et al. (1977). Women in Russia. Stanford University Press. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2017-03-27. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

(..) Ancient accounts link the Amazons with the Scythians and the Sarmatians, who successively dominated the south of Russia for a millennium extending back to the seventh century B.C. The descendants of these peoples were absorbed by the Slavs who came to be known as Russians.

- 1 2 Slovene Studies. 9–11. Society for Slovene Studies. 1987. p. 36.

(..) For example, the ancient Scythians, Sarmatians (amongst others), and many other attested but now extinct peoples were assimilated in the course of history by Proto-Slavs.

- ↑ Ivanchik, i

- ↑ Szemerényi, 1980 & see bibliography.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona (25 January 2017). "Scythians / Sacae". Livius. Archived from the original on 2018-02-01.

- ↑ Di Cosimo, Nicola, "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China (1,500 – 221 BC)", in: M. Loeuwe, E.L. Shaughnessy, eds, The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221BC, 1999, Cambridge University Press 1999,

ISBN 9780521470308

"They are used to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques. Archaeologists have used the term "Scythic continuum" in a broad cultural sense to indicate the early nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppe. The term "Scythic" draws attention to the fact that there are elements – shapes of weapons, vessels, and ornaments, as well as lifestyle – common to both the eastern and the western ends of the Eurasian steppe region." - ↑ Szemerényi, Oswald (1980) "Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian; Skudra; Sogdian; Saka" in: Sitzungsberichte der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; 371 = Scripta minora, vol. 4, pp. 2051–93 Azagoshnasp.net

- ↑ Herodotus 4.11 trans. G. Rawlinson.

- ↑ Drews (2004, p. 92)

- ↑ K Kristiansen. Europe Before History. Cambridge University Press. 1998, p 193

- ↑ "Colossians 3:11 NIV – Here there is no Gentile or Jew". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- 1 2 3 4 Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archaeology and Myth. Thames and Hudson. Read Chapter 2 and see 51–53 for a quick reference.

- ↑ See further:

- Szemerényi, Oswald (1980) "Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian; Skudra; Sogdian; Saka" in: Sitzungsberichte der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; 371 = Scripta minora, vol. 4, pp. 2051–93 Azagoshnasp.net

- Sulimirski, T. "The Scyths" in: The Cambridge History of Iran; vol. 2: 149–99 Azargoshnasp.net

- Grousset, René (1989) "The empire of the Steppes". Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; p. 19

- Jacobson, Esther. "The Art of Scythians", Brill Academic Publishers, 1995, pg 63 ISBN 90-04-09856-9

- Gamkrelidze and Ivanov. Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Typological Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture (Parts I and II). Tbilisi State University., 1984

- Newark, T. The Barbarians: Warriors and wars of the Dark Ages, Blandford: New York. See pages 65, 85, 87, 119–139.,1985

- Renfrew, C. Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European origins, Cambridge University Press, 1988

- Abaev, V.I. and H. W. Bailey, "Alans", Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. 1. pp. 801–803.;

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia, (translation of the 3rd Russian-language edition), 31 vols., New York, 1973–1983.

- Willem Vogelsang The rise & organisation of the Achaemenid empire – the eastern evidence (Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East Vol. III). Leiden: Brill. pp. 344., 1992 ISBN 90-04-09682-5.

- Sinor, Denis. Inner Asia: History – Civilization – Languages, Routledge, 1997 pg 82 ISBN 0-7007-0896-0 ;

- Masica, Colin P. The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press, 1993, pg 48 ISBN 0-521-29944-6

- ↑ Pavel Dolukhanov, The Early Slavs. Eastern Europe from the initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus. Longman, 1996. Pg 125

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- 1 2 Beckwith, Christopher (8 May 2011). Empires of the Silk Road (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-691-15034-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ↑ L. T. Yablonsky. "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty. ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-84826-002-3.

- 1 2 3 4 J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- 1 2 M. A. Dandamayev. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 BC to AD 250. UNESCO. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- 1 2 3 Bailey, H.W. (1996) "Khotanese Saka Literature", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint edition), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 1230.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume IV. Cambridge University Press. 24 November 1988. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre (29 July 2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

This is Kingdom which I hold, from the Scythians [Saka] who are beyond Sogdiana, thence unto Ethiopia [Cush]; from Sind, thence unto Sardis.

- ↑ Muhammad A. Dandamaev, Vladimir G. Lukonin (21 August 2008). The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-521-61191-6.

- ↑ "Haumavargā". Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ↑ L. T. Yablonsky. "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty. ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-84826-002-3.

- ↑ Barbara A. West. Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. p. 516.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (24 September 2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-19-968917-0.

- ↑ A. Sh. Shahbazi,. "Amorges". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (24 September 2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-968917-0.

- 1 2 3 Yu Taishan (June 2010). "The Earliest Tocharians in China" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers': 13–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ↑ J. P. mallory. "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Penn Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-09.

- ↑ "The Steppe: Scythian successes". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Loewe, Michael. (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 103–222. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 197–198. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377–462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 410–411. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press, pp 80–81, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- ↑ Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377–462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 377–388, 391, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Di Cosmo, Nicola. (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 174–189, 196–198, 241–242 ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- ↑ Benjamin, Craig. "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia". Archived from the original on 2015-02-18. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ Bernard, P. (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia". In Harmatta, János. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 96–126. ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- ↑ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp 21–22.

- ↑ "Yarkand". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2016-11-17. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1 (reprint edition) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 265.

- ↑ Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1 (reprint edition) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 265–266.

- ↑ Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). History of the Turks (突厥史). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, p. 596-598. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp 36, 146. ISBN 0-691-05494-0.

- ↑ Wechsler, Howard J.; Twitchett, Dennis C. (1979). Denis C. Twitchett; John K. Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–227. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- ↑ Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 0-253-35385-8.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani; B. A. Litvinsky; Unesco (1 January 1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- 1 2 Bailey, H.W. (1996) "Khotanese Saka Literature", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint edition), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 1230–1231.

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. (26 November 2011). "Chinese History – Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians Archived 2015-01-19 at the Wayback Machine.." ChinaKnowledge.de. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- ↑ see Zosimus, Historia Nova, 1.23 & 1.28, also Zonaras, Epitome historiarum, book 12. Also the title "Scythika" of the lost work of the 3rd-century Greek historian Dexippus who narrated the Germanic invasions of his age

- ↑ The Ossetes, the only Iranian people presently resident in Europe, call their country Iriston or Iron, though North Ossetia now officially has the designation Alania. They speak an Eastern Iranian language Ossetic, whose more widely spoken dialect, Iron or Ironig (i.e. Iranian), preserves some similarities with the Gathic Avestan language, another Iranian language of the Eastern branch

- ↑ Bernard S. Bachrach, A History of the Alans in the West, from their first appearance in the sources of classical antiquity through the early Middle Ages, University of Minnesota Press, 1973 ISBN 0-8166-0678-1

- ↑ Hughes, Dennis. (1991) Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece. Routledge pp. 10, 64–65, 118.

- ↑ Baldick, Julian. (2000) Animals and Shaman: Ancient Religions of Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. pp.35–36.

- ↑ Tsetskhladze, Gocha R. (2001) North Pontic Archaeology: Recent Discoveries and Studies. BRIL. pp. 5–474.