Iraqi Turkmen

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Predominately in the so-called "Turkmeneli" region Baghdad · Diyala · Erbil · Kirkuk · Nineveh · Saladin[8] | |

| Languages | |

| The Iraqi Turkmen dialect of Turkish is often called "Turkoman", "Turkmenelian" or "Turkmen". | |

| Religion | |

|

Mostly Secular Muslims Sunni Islam · Shia Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Syrian Turkmen · Turks in Lebanon | |

|

a The Iraqi government in its 1957 national census claimed there were 136,800 Turks in Iraq. However, the revised figure of 567,000 was issued by the Iraqi government after the 1958 revolution. The Iraqi government admitted that the minorities population was actually more than 400% from the previous year's total.[5][9][10] |

The Iraqi Turkmen (also spelled Turkoman, Turcoman, Turkomen, and Turkman; Turkish: Irak Türkmenleri), also referred to as Iraqi Turks, or Turks of Iraq (Arabic: تركمان العراق, Turkish: Irak Türkleri), are Iraqi citizens of Turkic origin who mostly adhere to a Turkish heritage and identity.[1][2] Most Iraqi Turkmen are the descendants of the Ottoman soldiers, traders and civil servants who were brought into Iraq from Anatolia during the rule of the Ottoman Empire.[11][12][3] Despite the popular reference to the Turks of Iraq as "Turkmen", they are not directly related to the Turkmen people of Turkmenistan and do not identify as such.

Today the Iraqi Turkmen form the third largest ethnic group in Iraq,[13][14][1] after the Arabs and Kurds. According to the Iraqi Ministry of Planning, in 2013, the Iraqi Turkmen population numbered 3 million out of Iraq's 34.7 million inhabitants.[1] The minority mainly reside in northern and central Iraq and share close cultural and linguistic ties with Turkey, particularly the Anatolian region.[15]

Disambiguation

The terms "Turkmen", "Turkman", and "Turkoman" have been used in the Middle East for centuries (particularly in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey) to define the common genealogical and linguistic ties of the Oghuz Turks in these regions. Consequently, the Iraqi Turkmen (as well as the Syrian Turkmen and Anatolian Turkmen) do not identifity themselves with the Turkmen people of Turkmenistan.[16] Sebastien Peyrouse, who is a senior research fellow with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, has summarised the terms thusly:

| “ | Many Turkic peoples who have lived for centuries in the Middle East have been called Turkmen, Turkman, and Turkoman without being seen a part of the Turkmen nation in the Turkmenistani meaning of the term... The majority of "Turkmen" in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey have been established there for several centuries and have no relationship with contemporary Turkmenistan. "Turkmen" is often used to designate Turkic-speakers in Arab areas, or Sunnis in Shitte areas. In this case, "Oghuz" more accurately identifies the common genealogical and linguistic ties.[16] | ” |

History

The Iraqi Turkmens are the descendants of various waves of Turkic migration to Mesopotamia beginning from the 7th century until the end of Ottoman rule (1919). The first wave of migration dates back to the 7th century, followed by migrations during the Seljuk Empire (1037–1194), the fleeing Oghuz during the Mongol destruction of the Khwarazmian dynasty (see Kara Koyunlu and Ag Qoyunlu), and the largest migration, during the Ottoman Empire (1535–1919). With the conquest of Iraq by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1534, followed by Sultan Murad IV's capture of Baghdad in 1638, a large influx of Turks—predominately from Anatolia—settled down in Iraq. Thus, most of today's Iraqi Turkmen are the descendants of the Ottoman soldiers, traders and civil servants who were brought into Iraq during the rule of the Ottoman Empire.[11][12][3][17]

Migration under Arab rule

The presence of Turkic peoples in what is today Iraq first began in the 7th century when approximately 2,000[18]–5,000[19][20] Oghuz Turks were recruited in the Muslim armies of Ubayd-Allah ibn Ziyad.[18] They arrived in 674 with the Umayyud conquest of Basra.[21] More Turkic troops settled during the 8th century, from Bukhara to Basra and also Baghdad.[21] During the subsequent Abbassid era, thousands more Turkmen warriors were brought into Iraq; however, the number of Turkmen who had settled in Iraq were not significant, as a result, the first wave of Turkmen became assimilated into the local Arab population.[18]

Seljuk migration

The second wave of Turkmen to descend on Iraq were the Turks of the Great Seljuq Empire.[11] Large scale migration of the Turkmen in Iraq occurred in 1055 with the invasion of Sultan Tuğrul Bey, the second ruler of the Seljuk dynasty, who intended to repair the holy road to Mecca. For the next 150 years, the Seljuk Turks placed large Turkmen communities along the most valuable routes of northern Iraq, especially Tel Afar, Erbil, Kirkuk, and Mandali, which is now identified by the modern community as Turkmeneli.[22] Many of these settlers assumed positions of military and administrative responsibilities in the Seljuk Empire.

Ottoman migration

The third, and largest, wave of Turkmen migration to Iraq arose during the four centuries of Ottoman rule (1535–1919).[11][23] By the first half of the sixteenth century the Ottomans had begun their expansion into Iraq, waging wars against their arch rival, the Persian Safavids.[24] In 1534, under the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, Mosul was sufficiently secure within the Ottoman Empire and became the chief province (eyalet) responsible for all other administrative districts in the region.[25] The Ottomans encouraged migration from Anatolia and the settlement of immigrant Turkmen along northern Iraq, religious scholars were also brought in to preach Hanafi (Sunni) Islam.[25] With loyal Turkmen inhabiting the area, the Ottomans were able to maintain a safe route through to the southern provinces of Mesopotamia.[11] Following the conquest, Kirkuk came firmly under Turkish control and was referred to as "Gökyurt",[26] it is this period in history whereby modern Iraqi Turkmen claim association with Anatolia and the Turkish state.[26]

.svg.png)

With the conquest of Iraq by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1534, followed by Sultan Murad IV's capture of Baghdad in 1638, a large influx of Turks settled down in the region.[20][12] After defeating the Safavids on December 31, 1534, Suleiman entered Baghdad and set about reconstructing the physical infrastructure in the province and ordered the construction of a dam in Karbala and major water projects in and around the city's countryside.[27] Once the new governor was appointed, the town was to be composed of 1,000 foot soldiers and another 1,000 cavalry.[28] However, war broke out after 89 years of peace and the city was besieged and finally conquered by Abbas the Great in 1624. The Persians ruled the city until 1638 when a massive Ottoman force, led by Sultan Murad IV, recaptured the city.[25] In 1639, the Treaty of Zuhab was signed that gave the Ottomans control over Iraq and ended the military conflict between the two empires.[29] Thus, more Turks arrived with the army of Sultan Murad IV in 1638 following the capture of Baghdad whilst others came even later with other notable Ottoman figures.[26][30]

Post-Ottoman era

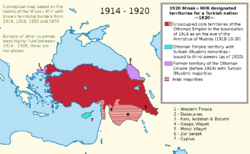

Following the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the Iraqi Turkmen wanted Turkey to annex the Mosul Vilayet and for them to become part of an expanded state;[31] this is because, under the Ottoman monarchy, the Iraqi Turkmen enjoyed a relatively trouble-free existence as the administrative and business classes.[31] However, due to the demise of the Ottoman monarchy, the Iraqi Turkmen participated in elections for the Constituent Assembly; the purpose of these elections was to formalise the 1922 treaty with Britain and obtain support for the drafting of a constitution and the passing of the 1923 Electoral law.[32] The Iraqi Turkmen made their participation in the electoral process conditional that the preservation of the Turkish character in Kirkuk's administration and the recognition of Turkish as the liwa's official language.[32] Although they were recognized as a constitutive entity of Iraq, alongside the Arabs and Kurds, in the constitution of 1925, the Iraqi Turkmen were later denied this status.[31]

Since the demise of the Ottoman Empire, the Iraqi Turkmens have found themselves increasingly discriminated against from the policies of successive regimes, such as the Kirkuk Massacre of 1923, 1947, 1959 and in 1979 when the Ba'th Party discriminated against the community.[31] Although they were recognized as a constitutive entity of Iraq (alongside the Arabs and Kurds) in the constitution of 1925, the Iraqi Turkmen were later denied this status.[31]

Culture

The Iraqi Turkmen are mostly Muslims and have close cultural and linguistic ties with the Anatolian region of Turkey.[15]

Language

The Iraqi Turkmen speak their own dialect of Turkish[33] and have particularly close linguistic ties with the Anatolian region of Turkey.[15] Under Article 4 of the Iraqi Constitution, the Iraqi Turkmen dialect is an official language in "the administrative units in which they constitute density of population". Article 4 (1) terms the language as "Turkmen" whilst Article 4 (4) terms it as "Turkoman".[34] Currently, the Iraqi Turkmen use the modern Turkish alphabet as the formal written language, in accordance with the 1997 Declaration of Principles adopted by the Iraqi Turkoman Congress, Article Three of which states the following:

| “ | The official written language of the Turkomans is Istanbul Turkish, and its alphabet is the new Latin alphabet.[35][36] | ” |

Due to the existence of different Turkish migration waves to Iraq for over 1,200 years, the Iraqi Turkmen dialect is by no means homogeneous.[37] Moreover, it has been influenced by several prestige languages in the region, Ottoman Turkish from 1534 onwards, and then Persian after the Capture of Baghdad (1624). Once the Ottomans took back Iraq in 1640, the Turkish varieties of Iraq continued to be influenced by Ottoman Turkish, as well as other languages in the region, such as Arabic and Kurdish.[37]

According to some linguists, the dialect spoken by Iraqi Turkmen is similar to the South Azeri dialect used by the Turkish Yörük tribes in the Balkans and Anatolia,[38][39] or intermediate between that and Istanbul Turkish (i.e., standard Turkish).[37] The dialect is particularly close to the Turkish dialects of Diyarbakır and Urfa in south-eastern Turkey.[40] Istanbul Turkish has long been the prestige dialect among Iraqi Turkmen and has exerted a profound historical influence on their dialect. Thus, the Iraqi Turkmen grammar differs sharply from Irano-Turkic varieties, such as South Azeri and Afshar types.[40]

Under the 1925 Iraqi Constitution, the use of Istanbul Turkish in schools, government offices and the media was allowed. Modern Turkish influence remained strong until the Arabic language became the new official language in the 1930s, and a degree of Turkmen–Turkish diglossia is still observable.[40] Restrictions on the Turkish language began in 1972 and intensified under Saddam Hussein's regime.[41][42]

Turkish speakers in Iraq are often bilingual or trilingual; Arabic is acquired through the mass media and through education at school whilst Kurdish is acquired in their neighbourhoods and through marriage.[37]

Education in Turkish

In 2005 Iraqi Turkmen community leaders decided that the Turkish language would replace the use of traditional Turkmeni in Iraqi schools;[43] Turkmeni had used the Arabic script whereas Turkish uses the Latin script (see Turkish alphabet).[43] Kelsey Shanks has argued that "the move to Turkish can be seen as a means to strengthen the collective "we" identity by continuing to distinguish it from the other ethnic groups... The use of Turkish was presented as a natural progression from the Turkmen; any suggestion that the oral languages were different was immediately rejected."[44]

Parental literacy rates in Turkish are low, as most are more familiar with the Arabic script (due to the Ba'athist regime). Therefore, the Turkmen Directorate of Education in Kirkuk has started Turkish language lessons for the wider society. Furthermore, the Ministry of Education Turkmen officer in Ninewa has requested to the "United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq" for the instigation of Turkish language classes for parents.[45]

Media in Turkish

The current prevalence of satellite television and media exposure from Turkey may have led to the standardisation of Turkmeni towards Turkish, and the preferable language for adolescents associating with the Turkish culture.[46]

In 2004 the Türkmeneli TV channel was launched in Kirkuk, Iraq. It broadcasts programmes in the Turkish and Arabic languages.[47] As of 2012, Türkmeneli TV has studios in Kirkuk and Baghdad in Iraq, and in the Çankaya neighbourhood in Ankara, Turkey.[47] Türkmeneli TV has signed agreements with several Turkish channels, such as TRT, TGRT and ATV, as well as with the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus's main broadcaster BRT, to share programmes and documentaries.[47]

Religion

The Iraqi Turkmen are predominately Muslims. The Sunni Turkmen form the majority (about 60%-70%) but there is also a significant number of Turkmen practicing the Shia branch of Islam (about 30% to 40%).[48][49] Nonetheless, the Turkmen are mainly secular, having internalized the secularist interpretation of state–religion affairs practiced in the Republic of Turkey since its foundation in 1923.[48] Moreover, the fact that the Turkmen mainly live in urban areas, where they deal with trade and commerce, and their tendency to acquire higher education, the power of religious and tribal factors inherent in Iraq’s political culture does not significantly affect the Turkmen.[50]

Demographics

Population

Official statistics

The Iraqi Turkmen are the third largest ethnic group in Iraq.[51][52] According to 2013 data from the Iraqi Ministry of Planning the Iraqi Turkmen have a population of about 3 million out of the total population of about 34.7 million (approximately 9% of the country's population).[2]

Past censuses and controversies

The 1957 Iraqi census (which is recognized as the last reliable census, as later censuses were reflections of the Arabization policies of the Ba'ath regime[53]) recorded 567,000 Turks out of a total population of 6.3 million, forming 9% of the total Iraqi population.[4][6][7][54] This put them third, behind Arabs and Kurds.[55] However, due to the undemocratic environment, their number has always been underestimated and has long been a point of controversy. For example, in the 1957 census, the Iraqi government first claimed that there was 136,800 Turks in Iraq. However, the revised figure of 567,000 was issued after the 1958 revolution when the Iraqi government admitted that the Iraqi Turkmen population was actually more than 400% from the previous year's total.[56] Scott Taylor has described the political nature of the results thusly:

| “ | According to the 1957 census conducted by King Faisal II — a monarch supported by the British — there were only 136,800 Turkmen in all of Iraq. Bearing in mind that since the British had wrested control of Mesopotamia from the Turks after the First World War, a deliberate campaign had been undertaken to eradicate or diminish all remnants of Ottoman influence. Therefore it should not be surprising that after Abdul Karim Kassem launched his successful revolution in 1958 – killing 23-year-old King Faisal II, expelling the British and declaring Iraq a republic – that a different set of numbers was published. According to the second census of 1958, the Turkmen registry stood at 567,000 – an increase of more than 400 per cent from the previous year's total.[5] | ” |

Subsequent censuses, in 1967, 1977, 1987 and 1997, are all considered highly unreliable, due to suspicions of regime manipulation.[57] The 1997 census states that there was 600,000[3][58] Iraqi Turkmen out of a total population of 22,017,983,[59] forming 2.72% of the total Iraqi population; however, this census only allowed its citizens to indicate belonging to one of two ethnicities, Arab or Kurd, this meant that many Iraqi Turkmen identified themselves as Arabs (the Kurds not being a desirable ethnic group in Saddam Hussein's Iraq), thereby skewing the true number of Iraqi Turkmen.[57]

Other estimates

In 2004 Scott Taylor suggested that the Iraqi Turkmen population accounted for 2,080,000 of Iraq's 25 million inhabitants (forming 8.32% of the population)[5] whilst Patrick Clawson has stated that the Iraqi Turkmen make up about 9% of the total population.[52] Furthermore, international organizations such as the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization has stated that the Iraqi Turkmen community is 3 million or 9–13% of the Iraqi population.[60][61] Iraqi Turkmen claim that their total population is over 3 million.[62][63][64] On the other hand, some Kurdish groups claim that the Iraqi Turkmen make up 2–3% of the Iraqi population, or approximately 500,000–800,000.[65]

Areas of settlement

The Iraqi Turkmen primarily inhabit northern Iraq, particularly in a region they refer to as "Turkmeneli" – which stretches from the northwest to the east at the middle of Iraq. Iraqi Turkmen consider their capital city to be Kirkuk.[51][62] Liam Anderson and Gareth Stansfield describe the Turkmeneli region as follows:

| “ | ...what Turkmens refer to as Turkmeneli – a vast swath of territory running from Iraq's border with Turkey and Syria and diagonally down the country to the border with Iran. Turkmen sources note that Turcomania – an anglicized version of "Turkmeneli" – appears on a map of the region published by William Guthrie in 1785, but there is no clear reference to Turkmeneli until the end of the twentieth century.[66] | ” |

The Iraqi Turkmen generally consider several major cities, and small districts associated with these cities, as part of Turkmeneli.[48] The major cities claimed to be a part of their homeland include: Altun Kupri, Badra, Bakuba, Diala, Erbil, Khanaqin, Kifri, Kirkuk, Kizilribat, Mendeli, Mosul, Salahaldeen, Sancar, Tal Afar, and Tuz Khurmatu.[48] Thus, the Turkmeneli region lies between the Arab areas of settlement to the south and Kurdish areas to the north.[48]

According to the 1957 census the Iraqi Turkmen formed the majority of inhabitants in the city of Kirkuk, with 40% declaring their mother toungue as "Turkish".[62][67] The second-largest Iraqi Turkmen city is Tel Afar where they make up 95% of the inhabitants.[68] The once mainly Turkoman cities of the Diyala Province and Kifri have been heavily Kurdified and Arabified.[61]

Some Iraqi Turkmen also live outside the Turkmeneli region. For example, there is a significant community living in Iraq's capital city of Baghdad.[48]

Diaspora

Most Iraqi Turkmen migrate to Turkey followed by Germany, Denmark, and Sweden.[69] Smaller communities have been formed in Canada, the United States, Australia,[69] Greece,[70] and the United Kingdom.[71]

Social issues

The position of the Iraqi Turkmen has changed from being administrative and business classes of the Ottoman Empire to an increasingly discriminated against minority.[31] Since the demise of the Ottoman Empire, the Iraqi Turkmen have been victims of several massacres, such as the Kirkuk Massacre of 1959. Furthermore, under the Ba'th party, discrimination against the Iraqi Turkmen increased, with several leaders being executed in 1979[31] as well as the Iraqi Turkmen community being victims of Arabization policies by the state, and Kurdification by Kurds seeking to push them forcibly out of their homeland.[72] Thus, they have suffered from various degrees of suppression and assimilation that ranged from political persecution and exile to terror and ethnic cleansing. Despite being recognized in the 1925 constitution as a constitutive entity, the Iraqi Turkmen were later denied this status; hence, cultural rights were gradually taken away and activists were sent to exile.[31]

Massacres

Massacre of 4 May 1924

In 1924, the Iraqi Turkmen were seen as a disloyal remnant of the Ottoman Empire, with a neutral tie to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's new Turkish nationalist ideology emerging in the Republic of Turkey.[73] Therefore, the Iraqi Turkmen living in the region of Kirkuk posed a threat to the stability of Iraq, particularly as they did not support the ascendancy of King Faisal I to the throne.[73] The Iraqi Turkmen were targeted by the British in collaboration with other Iraqi elements, of these, the most willing to subjugate the Iraqi Turkmen were the Iraq Levies—troops recruited from the Assyrian community that had sought refuge in Iraq from the Hakkari region of Turkey.[73] The spark for the conflict had been a dispute between a Levi soldier and an Iraqi Turkmen shopkeeper, which was enough for the British to allow the Levies to attack the Iraqi Turkmen, resulting in the massacre of some 200 people.[73]

Kirkuk massacre of 1959

The Kirkuk massacre of 1959 came about due to the Iraqi government allowing the Iraqi Communist Party, which in Kirkuk was largely Kurdish, to target the Iraqi Turkmen.[31][74] With the appointment of Maarouf Barzinji, a Kurd, as the mayor of Kirkuk in July 1959, tensions rose following the 14 July revolution celebrations, with animosity in the city polarizing rapidly between the Kurds and Iraqi Turkmen. On 14 July 1959, fights broke out between the Iraqi Turkmen and Kurds, leaving some 20 Iraqi Turkmen dead.[75] Furthermore, on 15 July 1959, Kurdish soldiers of the Fourth Brigade of the Iraqi army mortared Iraqi Turkmen residential areas, destroying 120 houses.[75][76] Order was restored on 17 July by military units from Baghdad. The Iraqi government referred to the incident as a "massacre"[77] and stated that between 31 and 79 Iraqi Turkmen were killed and some 130 injured.[75]

Arabization

In 1980, Saddam Hussein's government adopted a policy of assimilation of its minorities. Due to government relocation programs, thousands of Iraqi Turkmen were relocated from their traditional homelands in northern Iraq and replaced by Arabs, in an effort to Arabize the region.[78] Furthermore, Iraqi Turkmen villages and towns were destroyed to make way for Arab migrants, who were promised free land and financial incentives. For example, the Ba'th regime recognised that the city of Kirkuk was historically an Iraqi Arab city and remained firmly in its cultural orientation.[74] Thus, the first wave of Arabization saw Arab families move from the centre and south of Iraq into Kirkuk to work in the expanding oil industry. Although the Iraqi Turkmen were not actively forced out, new Arab quarters were established in the city and the overall demographic balance of the city changed as the Arab migrations continued.[74]

Several presidential decrees and directives from state security and intelligence organizations indicate that the Iraqi Turkmen were a particular focus of attention during the assimilation process during the Ba'th regime. For example, the Iraqi Military Intelligence issued directive 1559 on 6 May 1980 ordering the deportation of Iraqi Turkmen officials from Kirkuk, issuing the following instructions: "identify the places where Turkmen officials are working in governmental offices [in order] to deport them to other governorates in order to disperse them and prevent them from concentrating in this governorate [Kirkuk]".[79] In addition, on 30 October 1981, the Revolution's Command Council issued decree 1391, which authorized the deportation of Iraqi Turkmen from Kiruk with paragraph 13 noting that "this directive is specially aimed at Turkmen and Kurdish officials and workers who are living in Kirkuk".[79]

As primary victims of these Arabization policies, the Iraqi Turkmen suffered from land expropriation and job discrimination, and therefore would register themselves as "Arabs" in order to avoid discrimination.[80] Thus, ethnic cleansing was an element of the Ba'thist policy aimed at reducing the influence of the Iraqi Turkmen in northern Iraq's Kirkuk.[81] Those Iraqi Turkmen who remained in cities such as Kirkuk were subject to continued assimilation policies;[81] school names, neighbourhoods, villages, streets, markets and even mosques with names of Turkic origin were changed to names that emanated from the Ba'th Party or from Arab heroes.[81] Moreover, many Iraqi Turkmen villages and neighbourhoods in Kirkuk were simply demolished, particularly in the 1990s.[81]

Turkmen–Kurd tension

The Kurds claimed de facto sovereignty over land that Iraqi Turkmen regards as theirs. For the Iraqi Turkmen, their identity is deeply inculcated as the rightful inheritors of the region as a legacy of the Ottoman Empire.[82] Thus, it is claimed that the Kurdistan Region and Iraqi government has constituted a threat to the survival of the Iraqi Turkmen through strategies aimed at eradicating or assimilating them.[82] The largest concentration of Iraqi Turkmen tended to be in Tal Afar

According to Anderson and Stansfield, in the 1990s, tension between the Kurds and Iraqi Turkmen inflamed as the KDP and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) were institutionalized as the political hegemons of the region and, from the perspective of the Iraqi Turkmen, sought to marginalize them from the positions of authority and to subsume their culture with an all-pervading Kurdistani identity. With the support of Ankara, a new political front of Turkmen parties, the Iraqi Turkmen Front (ITF), was formed on 24 April 1995.[83] The relationship between the Iraqi Turkmen Front and the KDP was tense and deteriorated as the decade went on. Iraqi Turkmen associated with the Iraqi Turkmen Front complained about harassment by Kurdish security forces.[83] In March 2000, the Human Rights Watch reported that the KDP's security attacked the offices of the ITF in Erbil, killing two guards, following a lengthy period of disputes between the two parties.[83] In 2002, the KDP created an Iraqi Turkmen political organization, the Turkmen National Association, that supported the further institutionalization of the Kurdistan Region. This was viewed by pro-ITF Iraqi Turkmen as a deliberate attempt to "buy off" Iraqi Turkmen opposition and break their bonds with Ankara.[84] Promoted by the KDP as the "true voice" of the Iraqi Turkmen, the Turkmen National Association has a pro-Kurdistani stance and has effectively weakened the ITF as the sole representative voice of the Iraqi Turkmen.[84] Beginning in 2003, there were riots between Kurds and Turkmen in Kirkuk, a city that Turkmen views as historically theirs.[85]

Politics

Between ten and twelve Turkmen individuals were elected to the transitional National Assembly of Iraq in January 2005, including five on the United Iraqi Alliance list, three from the Iraqi Turkmen Front (ITF), and either two or four from the Democratic Patriotic Alliance of Kurdistan.[86][87]

In the December 2005 elections, between five and seven Turkmen candidates were elected to the Council of Representatives. This included one candidate from the ITF (its leader Saadeddin Arkej), two or four from the United Iraqi Alliance, one from the Iraqi Accord Front and one from the Kurdistani Alliance.[87][88]

Iraqi Turkmen have also emerged as a key political force in the controversy over the future status of northern Iraq and the Kurdish Autonomous Region. The government of Turkey has helped fund such political organizations as the Iraqi Turkmen Front, which opposes Iraqi federalism and in particular the proposed annexation of Kirkuk to the Kurdistan Regional Government.[89]

Tensions between the two groups over Kirkuk, however, have slowly died out and on January 30, 2006, the President of Iraq, Jalal Talabani, said that the "Kurds are working on a plan to give Iraqi Turkmen autonomy in areas where they are a majority in the new constitution they're drafting for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq."[90] However, it never happened and the policies of Kurdification by KDP and PUK after 2003 (with non-Kurds being pressed to move) have prompted serious inter-ethnic problems.[91]

Notable people

- Arshad al-Salihi, politician

- Farah Zeynep Abdullah, Turkish actress[92]

- Jafar al-Askari, former Prime Minister of Iraq (1923–24 and 1926–27)[93]

- Abbas al-Bayati, politician[94]

- Yasin al-Hashimi, former Prime Minister of Iraq (1924–25 and 1935–36)[93]

- Abd al-Muhsin as-Sa'dun, former Prime Minister of Iraq (1922–23, 1925–26, 1928–29 and 1929)[93]

- Nuri al-Said, former Prime Minister of Iraq (1930–32, 1938–40, 1941–44, 1946–47, 1949, 1950–52, 1954–57 and 1958)[93]

- Selim Bayraktar, Turkish actor[95]

- Hijri Dede, poet

- İhsan Doğramacı, founder of Bilkent University and Hacettepe University[96]

- Sinan Erbil singer

- Saadeddin Arkej, politician

- Amine Gülşe, Winner of Miss Turkey (2014) and actress[97]

- İsmet Hürmüzlü, Turkish actor[98]

- Jasim Mohammed Jaafar, Minister for Youth & Sports[94]

- Gökhan Kırdar, Turkish musician[99]

- Lütfi Kırdar, Turkish politician[100]

- Nemir Kirdar, businessman[101]

- Rena Kirdar, author and socialite

- Üner Kırdar, Turkish diplomat and senior United Nations official[100]

- Younis Mahmoud, football player[102]

- Reha Muhtar, Turkish television personality[103]

- Talib Mushtaq, poet and diplomat[104]

- Salih Neftçi, Turkish economist[105]

- Rashad Mandan Omar, Minister of Science and Technology (2003)[106]

- Fahmi Said, army officer[107]

- Hikmat Sulayman, former Prime Minister of Iraq (1936–37)[108]

- Mehmet Türkmehmet, football player

- Ali Saip Ursavaş, Turkish politician

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Triana, María (2017), Managing Diversity in Organizations: A Global Perspective, Taylor & Francis, p. 168, ISBN 1-317-42368-2,

Turkmen, Iraqi citizens of Turkish origin, are the third largest ethnic group in Iraq after Arabs and Kurds, and they are said to number about 3 million of Iraq's 34.7 million citizens according to the Iraqi Ministry of Planning.

- 1 2 3 Bassem, Wassim (2016). "Iraq's Turkmens call for independent province". Al-Monitor.

Iraqi Turkmens, who are citizens of Iraq with Turkish origins, have been calling for their own independent province in the Tal Afar district west of Mosul, located in the center of the Ninevah province...Turkmens are a mix of Sunnis and Shiites and are the third-largest ethnicity in Iraq after Arabs and Kurds, numbering around 3 million out of the total population of about 34.7 million, according to 2013 data from the Iraqi Ministry of Planning.

- 1 2 3 4 International Crisis Group (2008), Turkey and the Iraqi Kurds: Conflict or Cooperation?, Middle East Report N°81 –13 November 2008: International Crisis Group, archived from the original on 12 January 2011,

Turkomans are descendents of Ottoman Empire-era soldiers, traders and civil servants... The 1957 census, Iraq’s last reliable count before the overthrow of the monarchy in 1958, put the country’s population at 6,300,000 and the Turkoman population at 567,000, about 9 per cent...Subsequent censuses, in 1967, 1977, 1987 and 1997, are all considered highly problematic, due to suspicions of regime manipulation.

- 1 2 Knights, Michael (2004), Operation Iraqi Freedom And The New Iraq: Insights And Forecasts, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, p. 262, ISBN 0-944029-93-0,

The 1957 Iraqi census — the last in which the Turkmens were permitted to register — counted 567,000 Turkmens

. - 1 2 3 4 Taylor, Scott (2004), Among the Others: Encounters with the Forgotten Turkmen of Iraq, Esprit de Corps Books, p. 28, ISBN 1-895896-26-6

- 1 2 Güçlü, Yücel (2007), Who Owns Kirkuk? The Turkoman Case (PDF), Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2007, p. 79,

The last reliable census in Iraqi – and the only one in which participants could declare their mother tongue – was in 1957. It found that Turkomans were the third largest ethnicity in Iraq, after Arabs and Kurds. The Turkomans numbered 567,000 out of a total population of 6,300,000.

- 1 2 Betts, Robert Brenton (2013), The Sunni-Shi'a Divide: Islam's Internal Divisions and Their Global Consequences, Potomac books, University of Nebraska Press, p. 86

- ↑ Al-Shawi, Ibrahim (2006), A Glimpse of Iraq, Lulu, ISBN 1-4116-9518-6

- ↑ Kocak, Ali (8 May 2007). "The Reality of the Turkmen Population in Iraq". Turkish Weekly. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- ↑ Al-Hirmizi, Ershad (2003), The Turkmen And Iraqi Homeland (PDF), Kerkuk Vakfi, p. 124

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Taylor, Scott (2004), Among the Others: Encounters with the Forgotten Turkmen of Iraq, Esprit de Corps, p. 31, ISBN 1-895896-26-6,

The largest number of Turkmen immigrants followed the army of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent when he conquered all of Iraq in 1535. Throughout their reign, the Ottomans encouraged the settlement of immigrant Turkmen along the loosely formed boundary that divided Arab and Kurdish settlements in northern Iraq.

- 1 2 3 4 Jawhar, Raber Tal'at (2010), "The Iraqi Turkmen Front", in Catusse, Myriam; Karam, Karam (eds.), Returning to Political Parties?, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, pp. 313–328, ISBN 1-886604-75-4,

There’s a strong conflict of opinions regarding the origins of Iraqi Turkmen, however, it is certain that they settled down during the Ottoman rule in the northwest of Mosul, whence they spread to eastern Baghdad. Once there, they became high ranked officers, experts, traders, and executives in residential agglomerations lined up along the vast, fertile plains, and mingled with Kurds, Assyrians, Arabs, and other confessions. With the creation of the new Iraqi state in 1921, Iraqi Turkmen managed to maintain their socioeconomic status.

- ↑ Sadik, Giray (2009), American Image in Turkey: U.S. Foreign Policy Dimensions, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 13, ISBN 0-7391-3380-2,

the Turkmen are Iraq's third-largest ethnic group after the Arabs and Kurds

- ↑ Barker, Geoff (2012), Iraq, Britannica, p. 23, ISBN 1-61535-637-1,

The Turkish-speaking Turkmen are the third-largest ethnic group in Iraq after the Arabs and the Kurds.

- 1 2 3 BBC (June 18, 2004). "Who's who in Iraq: Turkmen". Retrieved 2011-11-23.

The predominantly Muslim Turkmen are an ethnic group with close cultural and linguistic ties to Anatolia in Turkey.

- 1 2 Peyrouse, Sebastien (2015), Turkmenistan: Strategies of Power, Dilemmas of Development, Routledge, p. 62, ISBN 0-230-11552-7

- ↑ Library of Congress, Iraq: Other Minorities, Library of Congress, retrieved 2011-11-24,

The Turkomans, who speak a Turkish dialect, have preserved their language but are no longer tribally organized. Most are Sunnis who were brought in by the Ottomans to repel tribal raids.

- 1 2 3 Taylor 2004, 30.

- ↑ Anderson, Liam D.; Stansfield, Gareth R. V. (2009), Crisis in Kirkuk: The Ethnopolitics of Conflict and Compromise, University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 15

- 1 2 3 Stansfield, Gareth R. V. (2007), Iraq: People, History, Politics, Polity, p. 70

- 1 2 Barry Rubin (17 March 2015). The Middle East: A Guide to Politics, Economics, Society and Culture. Routledge. pp. 528–529. ISBN 978-1-317-45578-3.

- ↑ Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 16.

- ↑ Stansfield 2007, 70.

- ↑ Fattah, Hala; Caso, Frank (2009), "Turkish Tribal Migrations and the Early Ottoman State", A Brief History of Iraq, Infobase Publishing, p. 115

- 1 2 3 Fattah & Caso 2009, 116.

- 1 2 3 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 17.

- ↑ Fattah & Caso 2009, 117.

- ↑ Fattah & Caso 2009, 118.

- ↑ Fattah & Caso 2009, 120.

- ↑ Talabany, Nouri (2007), Who Owns Kirkuk? The Kurdish Case, Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2007, p. 75

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Stansfield 2007, 72.

- 1 2 Lukitz, Liora (1995), Iraq: The Search for National Identity, Routledge, p. 41

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency. "The World Factbook: Iraq". Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ↑ The Republic of Iraq Ministry of Interior, Iraqi Constitution (PDF), pp. 2–3, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2016, retrieved 18 October 2016

- ↑ Türkmeneli İşbirliği ve Kültür Vakfı. "Declaration of Principles of the (Iraqi?) Turkman Congress". Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ Nissman, David (5 March 1999), "The Iraqi Turkomans: Who They Are and What They Want", Iraq Report, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2 (9)

- 1 2 3 4 Bulut, Christiane (2000), "Optative constructions in Iraqi Turkmen", in Göksel, Aslı; Kerslake, Celia (eds.), Studies on Turkish and Turkic Languages, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-04293-1

- ↑ Boeschoten, Hendrik (1998), "Speakers of Turkic Languages", in Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Ágnes, The Turkic Languages, Routledge, p. 5,

There is a Turkish – or rather Azerbaijanian-speaking part of the population of northern Iraq which is sometimes called "Turkmen", similar to the Yuruk tribes in the Balkans and in Anatolia.

- ↑ Bayatlı, Hidayet Kemal (1996), İrak Türkmen Türkçesi, Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu, p. 329, ISBN 9789751608338,

Türkmenlerinin konuştukları ağız, Türkçenin Azeri ağzı (Doğu Oğuzca) sahası içine girmektedir. Azeri sahası dil coğrafyası bakımından: Doğu Anadolu, Güney Kafkasya, Kafkas Azerbaycan'ı, İran Azerbaycan'ı, Kerkük (lrak) ve Suriye Türkleri bölgelerini kapsar.

- 1 2 3 Johanson, Lars (2001), Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map (PDF), Stockholm: Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul, pp. 15–16,

The modern Turkish influence was strong until Arabic became the new offıcial language in the 1930s. A certain diglossia Turkish vs. Iraqi Turkic is still observable. Turkish as a prestige language has exerted profound influence on Iraqi Turkic. Thus, the syntax differs sharply from neighboring Irano-Turkic varieties.

- ↑ Al-Shawi, Ibrahim (2006), A Glimpse of Iraq, Lulu, p. 47

- ↑ Abdul Hameed, Bakier (March 18, 2008). "Iraqi Turkmen Announce Formation of New Jihadi Group". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- 1 2 Shanks, Kelsey (2016), Education and Ethno-Politics: Defending Identity in Iraq, Routledge, p. 57, ISBN 1-317-52043-2

- ↑ Shanks 2016, 60.

- ↑ Shanks 2016, 59.

- ↑ Shanks 2016, 58.

- 1 2 3 "Türkmeneli Tv-Radyo Genel Yayın Yönetmeni Yalman Hacaroğlu ile Söyleşi". ORSAM. 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oğuzlu, Tarik H. (2004), "Endangered community:The Turkoman identity in Iraq", Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Routledge, 24 (2): 313

- ↑ Jawhar, Raber Tal'at (2010), "The Iraqi Turkmen Front", in Catusse, Myriam; Karam, Karam (eds.), Returning to Political Parties?, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, pp. 313–328, ISBN 1-886604-75-4,

In short, Iraqi Turkmen are a unique ethnic group; they are predominantly Muslim and divided into two main sects: Shiites (40%) Sunnites (60%), and have strong cultural ties with Turkey

- ↑ Oğuzlu 2004, 314.

- 1 2 Al-Hurmezi, Ahmed (9 December 2010), The Human Rights Situation of the Turkmen Community in Iraq, Middle East Online, retrieved 2011-10-31

- 1 2 Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. "Iraqi Turkmen: The Human Rights Situation and Crisis in Kerkuk" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 43

- ↑ Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 58

- ↑ Gunter, Michael M. (2004), "The Kurds in Iraq" (PDF), Middle East Policy, 11 (1): 131

- ↑ Taylor 2004, 79.

- 1 2 International Crisis Group 2008, 16.

- ↑ Phillips, David L. (2006), Losing Iraq: Inside the Postwar Reconstruction Fiasco, Basic Books, p. 304, ISBN 0-465-05681-4,

Behind the Arabs and the Kurds, Turkmen are the third-largest ethnic group in Iraq. The ITF claim Turkmen represent 12 percent of Iraq's population. In response, the Kurds point to the 1997 census which showed that there were only 600,000 Turkmen.

- ↑ Graham-Brown, Sarah (1999), Sanctioning Saddam: The Politics of Intervention in Iraq, I.B.Tauris, p. 161

- ↑ Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. "Iraqi Turkmen". Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- 1 2 Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. "The Turkmen of Iraq: Underestimated, Marginalized and exposed to assimilation Terminology". Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- 1 2 3 Park, Bill (2005), Turkey's policy towards northern Iraq: problems and perspectives, Taylor & Francis, p. 32

- ↑ Kibaroğlu, Mustafa; Kibaroğlu, Ayșegül; Halman, Talât Sait (2009), Global security watch Turkey: A reference handbook, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 165

- ↑ Iraqi Turkmen: Push for Self-Determination Gains Momentum

- ↑ Jenkins, Gareth (2008), Turkey and Northern Iraq: An Overview (PDF), The Jamestown Foundation, p. 6

- ↑ Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 56.

- ↑ O'Leary, Brendan (2009), How to get out of Iraq with integrity, University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 152

- ↑ Hashim, Ahmed (2005), Insurgency and counter-insurgency in Iraq, Cornell University Press, p. 370

- 1 2 Sirkeci, Ibrahim (2005), Turkmen in Iraq and International Migration of Turkmen (PDF), University of Bristol, p. 2-

- ↑ Wanche, Sophia I. (2004), An Assessment of the Iraqi Communityin Greece (PDF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, p. 3

- ↑ International Organization for Migration (2007), Iraq Mapping Exercise (PDF), International Organization for Migration, p. 5, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16

- ↑ Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 62.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 63.

- 1 2 3 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 64.

- 1 2 3 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 34.

- ↑ Ghanim, David (2011), Iraq's Dysfunctional Democracy, ABC-CLIO, p. 380

- ↑ Entessar, Nader (2010), Kurdish Politics in the Middle East, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 79

- ↑ Jenkins 2008, 15.

- 1 2 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 65.

- ↑ International Crisis Group 2006, 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 66.

- 1 2 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 67.

- 1 2 3 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 68.

- 1 2 Anderson & Stansfield 2009, 69.

- ↑ The Legacy of Iraq by Benjamin Isakhan Edinburgh University Press.

- ↑ Interesting Outcomes in Iraqi Election Archived 2005-11-03 at the Wayback Machine., Zaman Daily Newspaper

- 1 2 The New Iraq, The Middle East and Turkey: A Turkish View Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine., Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, 2006-04-01, accessed on 2007-09-06

- ↑ Turkmen Win Only One Seat in Kerkuk Archived 2008-06-19 at the Wayback Machine., Iraqi Turkmen Front

- ↑ Kurds Accused Of Rigging Kirkuk Vote Archived 2006-08-21 at the Wayback Machine., Al Jazeera

- ↑ Cevik, Ilnur (2006-01-30). "Talabani: Autonomy for Turkmen in Kurdistan". Kurdistan Weekly. Retrieved 2006-05-20.

- ↑ Stansfield 2007, 71.

- ↑ Milliyet (August 16, 2013). "Engin Akyürek'in yeni sinema filmi, "Bir Eylül Meselesi"". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

Farah Zeynep Abdullah,Iraklı Türkmen kökenli baba ve bir Türk annenin kızıdır

- 1 2 3 4 Nakash, Yitzhak (2011), Reaching for Power: The Shi'a in the Modern Arab World, Princeton University Press, p. 87

- 1 2 Today's Zaman (August 16, 2010). "Davutoğlu meets Iraq's Turkmen politicians, urges unity". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Batuman, Elift (Feb 17, 2014). "Letter From Istanbul: Ottomania A his TV show reimagines Turkey's imperial past". The New Yorker. Missing or empty

|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Bilkent News, Elift (Feb 26, 2010). "Bilkent Mourns the Loss of its founder, Prof. Ihsan Dogramaci" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Hurriyet (17 October 2016). "Kerküklü Türkmen oyuncu Amine Gülşe Arapçayı biraz biliyorum".

- ↑ Sabah (January 20, 2013). "İsmet Hürmüzlü'yü kaybettik". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Milliyet (February 22, 2012). ""Yerine Sevemem" ölümsüz aşk hikayeleri projesi!". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- 1 2 Kirdar 2012, 4.

- ↑ Kirdar 2012, 3.

- ↑ Greenwell, Megan (July 30, 2007). "Jubilant Iraqis Savor Their Soccer Triumph". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Milliyet. "Türkmenler, Irak'ta eğitim düzeyleriyle öne çıkıyor..." Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Wien, Peter (2014), Iraqi Arab Nationalism: Authoritarian, Totalitarian and Pro-Fascist Inclinations, 1932–1941, Routledge, p. 30

- ↑ Milliyet. "Salih Neftçi". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ BBC (2004). "Interim Iraqi government". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Al-Marashisa, Ibrahim; Salama, Sammy (2008), Iraq's Armed Forces: An Analytical History, Routledge, p. 52, ISBN 1-134-14564-0,

Fahmi Said was from Sulaymaniyya, his father an Arab from the Anbak tribe situated near the Tigris and his mother was of Turkish origin.

- ↑ Wien 2014, 10.

Bibliography

- Al-Hirmizi, Ershad (2003), The Turkmen And Iraqi Homeland (PDF), Kerkuk Vakfi

- Al-Shawi, Ibrahim (2006), A Glimpse of Iraq, Lulu, ISBN 1-4116-9518-6

- Anderson, Liam D.; Stansfield, Gareth R. V. (2009), Crisis in Kirkuk: The Ethnopolitics of Conflict and Compromise, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-4176-2

- Barker, Geoff (2012), Iraq, Britannica, ISBN 1-61535-637-1

- Bayatlı, Hidayet Kemal (1996), İrak Türkmen Türkçesi, Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu, p. 329, ISBN 9789751608338

- Betts, Robert Brenton (2013), The Sunni-Shi'a Divide: Islam's Internal Divisions and Their Global Consequences, Potomac books, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 1-61234-522-0

- Boeschoten, Hendrik (1998), "Speakers of Turkic Languages", in Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Ágnes, The Turkic Languages, Routledge

- Bulut, Christiane (2000), "Optative constructions in Iraqi Turkmen", in Göksel, Aslı; Kerslake, Celia (eds.), Studies on Turkish and Turkic Languages, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-04293-1

- Entessar, Nader (2010), Kurdish Politics in the Middle East, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7391-4039-6

- Fattah, Hala; Caso, Frank (2009), "Turkish Tribal Migrations and the Early Ottoman State", A Brief History of Iraq, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 0-8160-5767-2

- Ghanim, David (2011), Iraq's Dysfunctional Democracy, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 0-313-39801-1

- Gunter, Michael M. (2004), "The Kurds in Iraq" (PDF), Middle East Policy, 11 (1): 106–131, doi:10.1111/j.1061-1924.2004.00145.x

- Graham-Brown, Sarah (1999), Sanctioning Saddam: The Politics of Intervention in Iraq, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-86064-473-2

- Güçlü, Yücel (2007), Who Owns Kirkuk? The Turkoman Case (PDF), Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2007

- Hashim, Ahmed (2005), Insurgency and counter-insurgency in Iraq, Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-4452-7

- International Crisis Group (2006), Iraq and the Kurds: The Brewing Battle Over Kirkuk (PDF), Middle East Report N°56 – 18 July 2006: International Crisis Group

- International Crisis Group (2008), Turkey and the Iraqi Kurds: Conflict or Cooperation?, Middle East Report N°81 –13 November 2008: International Crisis Group, archived from the original on 12 January 2011

- Jawhar, Raber Tal'at (2010), "The Iraqi Turkmen Front", in Catusse, Myriam; Karam, Karam (eds.), Returning to Political Parties?, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies

- Jenkins, Gareth (2008), Turkey and Northern Iraq: An Overview (PDF), The Jamestown Foundation

- Johanson, Lars (2001), Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map (PDF), Stockholm: Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul

- Johanson, Lars (2009), "Turkmen", in Brown, Keith; Sarah, Ogilvie (eds.), Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Elsevier, ISBN 0-08-087774-5 .

- Kibaroğlu, Mustafa; Kibaroğlu, Ayșegül; Halman, Talât Sait (2009), Global security watch Turkey: A reference handbook, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-34560-0

- Kirdar, Nemir (2012), In Pursuit of Fulfilment: Principle Passion Resolve, Hachette, ISBN 0-297-86951-5

- Knights, Michael (2004), Operation Iraqi Freedom And The New Iraq: Insights And Forecasts, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, ISBN 0-944029-93-0

- Lukitz, Liora (1995), Iraq: The Search for National Identity, Routledge, ISBN 0-7146-4550-8

- Lukitz, Liora (2006), A quest in the Middle East: Gertrude Bell and the making of modern Iraq, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-415-8

- Nakash, Yitzhak (2011), Reaching for Power: The Shi'a in the Modern Arab World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 1-4008-4146-1

- Oğuzlu, Tarik H. (2004), "Endangered community:The Turkoman identity in Iraq", Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Routledge, 24 (2)

- O'Leary, Brendan (2009), How to get out of Iraq with integrity, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-4201-7

- Park, Bill (2005), Turkey's policy towards northern Iraq: problems and perspectives, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-38297-1

- Phillips, David L. (2006), Losing Iraq: Inside the Postwar Reconstruction Fiasco, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-05681-4

- Rubin, Barry (17 March 2015), The Middle East: A Guide to Politics, Economics, Society and Culture, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-45578-3

- Ryan, J. Atticus; Mullen, Christopher A. (1998), Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: Yearbook 1997, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, ISBN 90-411-1022-4

- Sadik, Giray (2009), American Image in Turkey: U.S. Foreign Policy Dimensions, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7391-3380-2

- Shanks, Kelsey (2016), Education and Ethno-Politics: Defending Identity in Iraq, Routledge, ISBN 1-317-52043-2

- Sirkeci, Ibrahim (2005), Turkmen in Iraq and International Migration of Turkmen (PDF), University of Bristol

- Stansfield, Gareth R. V. (2007), Iraq: People, History, Politics, Polity, ISBN 0-7456-3227-0

- Talabany, Nouri (2007), Who Owns Kirkuk? The Kurdish Case, Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2007

- Taylor, Scott (2004), Among the Others: Encounters with the Forgotten Turkmen of Iraq, Esprit de Corps Books, ISBN 1-895896-26-6

- Triana, María (2017), Managing Diversity in Organizations: A Global Perspective, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 1-317-42368-2

- Wien, Peter (2014), Iraqi Arab Nationalism: Authoritarian, Totalitarian and Pro-Fascist Inclinations, 1932–1941, Routledge, ISBN 1-134-20479-5 .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iraqi Turkmen. |