Sardinian people

| Sardos / Sardus (Sardinian) Sardi (Italian) Sards / Sardos (Catalan) | |

|---|---|

Sardinian people and their traditional regional attires in 1880s | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

|

1,661,521 (Inhabitants of Sardinia, regardless of ethnicity rather than ethnic Sards)[1] | |

| Languages | |

|

Italian (as a result of language shift) • Sardinian • Other languages • Historically Spanish and Catalan | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Christian (Roman Catholicism[2]) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Italians, Spaniards (Basques)[3] and French (Corsicans)[4][5] |

The Sardinians,[6] or also the Sards[7] (Sardinian: Sardos or Sardus; Italian and Sassarese: Sardi; Catalan: Sards or Sardos; Gallurese: Saldi; Ligurian: Sordi), are the native people and Romance[8] ethnic group[9][10][11] from which Sardinia, a western Mediterranean island and autonomous region of Italy, derives its name.[12][13]

Etymology

The ethnonym "S(a)rd" belongs to the Pre-Indo-European linguistic substratum. The oldest written attestation of the ethnonym is on the Nora stone, where the word Šrdn bears witness to its original existence by the time the Phoenician merchants first arrived to the Sardinian shores.[14] According to Timaeus, one of Plato's dialogues, Sardinia and its people as well, the "Sardonioi" or "Sardianoi" (Σαρδονιοί or Σαρδιανοί), might have been named after "Sardò" (Σαρδώ), a legendary woman from Sardis (Σάρδεις), capital of the ancient Kingdom of Lydia in Anatolia.[15][16] Pausanias and Sallust reported instead that Sardinians traced their descent back to a mythical ancestor, a Libyan son of Hercules or Melqart revered as Sardus Pater Babai ("Sardinian Father"), who gave the island its name.[17] It has also been claimed that the ancient Nuragic Sards were associated with the Sherden (šrdn in Egyptian), one of the Sea Peoples.[18][19][20][21] The ethnonym was then romanised, with regard for the singular masculine and feminine form, as sardus and sarda.

History

Prehistory

Sardinia was first colonized in a stable manner during the Upper Paleolithic and the Mesolithic by people from the Iberian and the Italian peninsula. During the Neolithic period and the Early Eneolithic, people from Italy, Spain and the Aegean area settled in Sardinia. In the Late Eneolithic-Early Bronze age the "Beaker folk" from Southern France, Northeastern Spain and then from Central Europe[22] settled on the island, bringing new metallurgical techniques and ceramic styles and probably some kind of Indo-European speech.[23]

Nuragic civilization

The Nuragic civilization arose in the Middle Bronze Age, during the Late Bonnanaro culture, which showed connections with the previous Beaker culture and the Polada culture of northern Italy. At that time, the grand tribal identities of Nuragic Sardinia were said to be three (roughly from the South to the North): the Iolei/Ilienses, inhabiting the area from the southernmost plains to the mountainous zone of eastern Sardinia (later part of what would be called by the Romans Barbaria); the Balares, living in the North-West corner; and finally the Corsi stationed in Gallura (and Corsica, to which they gave the name).[24] Nuragic Sardinians have been connected by some scholars to the Sherden, a tribe of the so-called Sea Peoples, whose presence is registered several times in ancient Egyptian records.[25]

The language (or languages) spoken in Sardinia during the Bronze Age is unknown, since there are no written records of such period. According to Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, the Proto-Sardinian language was akin to Proto-Basque and the ancient Iberian, while others believe it was related to Etruscan. Other scholars theorize that there were actually various linguistic areas (two or more) in Nuragic Sardinia, possibly Pre-Indoeuropeans and Indoeuropeans.[26]

Antiquity

In the 9th century BC, the Phoenicians founded cities and ports along the south-west coast, such as Karalis, Bithia, Sulki and Tharros.

The south and west part of Sardinia was annexed by the Carthaginians in the late 6th century BC and later the whole island was conquered by the Romans in the 3rd century BC, after the First Punic War. Sardinia and Corsica were then made into a single province.

Sardinia, with the exception of the innerlands and especially the central mountainous area called Barbagia (Barbaria in Latin), was heavily Latinized during the Roman period, and the modern Sardinian language is considered one of the most conservative Romance languages.[27][28][29] Besides, during the Roman rule there was a considerable immigration flow from the Italian peninsula into the island; ancient sources mention several populations of likely Italic origin settling down in Sardinia, like the Patulcenses Campani (from Campania), the Falisci (from southern Etruria), the Buduntini (from Apulia) and the Siculenses (from Sicily). Roman colonies were also established in Porto Torres (Turris Libisonis) and Usellus.[30] Strabo gave a brief summary about the Mountaineer tribes, living in what would be called civitates Barbariae, who refused assimilation during Roman rule, Geographica V ch.2:

There are four nations of mountaineers, the Parati, Sossinati, Balari, and the Aconites. These people dwell in caverns. Although they have some arable land, they neglect its cultivation, preferring rather to plunder what they find cultivated by others, whether on the island or on the continent, where they make descents, especially upon the Pisatæ. The prefects sent [into Sardinia] sometimes resist them, but at other times leave them alone, since it would cost too dear to maintain an army always on foot in an unhealthy place.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Sardinia was ruled in rapid succession by the Vandals, the Byzantines, the Ostrogoths[31] and again by the Byzantines.

During the Middle Ages, the island was divided into four independent Kingdoms (known individually in Sardinian as Judicadu, Giudicau or simply Logu, that is "place"; in Italian: Giudicato); all of them, with the exception of that of Arborea, fell under the influence of the Genoese and Pisan maritime republics, as well as some noble families of the two cities, like the Doria and the Della Gherardesca. The Doria founded the cities of Alghero and Castelgenovese (today Castelsardo), while the Pisans founded Castel di Castro (today Cagliari) and Terranova (today Olbia); the famous count Ugolino della Gherardesca, quoted by Dante Alighieri in his Divine Comedy, favored the birth of the mining town of Villa di Chiesa (today Iglesias), which became an Italian medieval commune along with Sassari and Castel di Castro.

Following the Aragonese conquest of the Sardinian territories belonging to Pisa, which took place between 1323 and 1326, and then the long conflict between the Aragonese Kingdom and the Giudicato of Arborea (1353–1420), the newborn Kingdom of Sardinia became one of the states of the Crown of Aragon. The Aragonese repopulated the cities of Castel di Castro and Alghero with Iberian colonists, mainly Catalans.[32][33] A local dialect of Catalan is still spoken by a minority of people in the city of Alghero.

Modern and contemporary history

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the main Sardinian cities of Cagliari (the capital of the Kingdom), Alghero and Sassari appear well placed in the trades of the time. The cosmopolitan composition of its people provides evidence of it: the population was not only indigenous, but also hailing from Spain, Liguria, France and the island of Corsica in particular.[34][35][36] Especially in Sassari and across the strip of territory that goes from Anglona to Gallura, the Corsicans became the majority of the population at least since the 15th century.[36] This migration from the neighboring island, which is likely to have led to the birth of the Tuscan-sounding Sassarese and Gallurese dialects,[36] went on continuously until the 19th century.

The Spanish era ended in 1713, when the whole island was ceded to the Austrian House of Habsburg, followed with another cession in 1718 to the Dukes of Savoy, who assumed the title of "Kings of Sardinia". During this period, Ligurian colonists, escaped from Tabarka, settled on the little islands of San Pietro and Sant'Antioco (at Carloforte and Calasetta), in the south-west area of Sardinia, bringing with them a Gallo-Italic dialect called "Tabarchino", still widely spoken there. Then, the Piedmontese Kingdom of Sardinia annexed the whole Italian peninsula and Sicily in 1861 after the Risorgimento, becoming the Kingdom of Italy.

Since 1850, with the reorganization of the Sardinian mines, there had been a considerable migration flow from the Italian peninsula towards the Sardinian mining areas; these mainland miners came mostly from Lombardy, Piedmont, Tuscany and Romagna.[37][38] According to an 1882 census realised by the French engineer Leon Goüine, in the south-western Sardinian mines worked 10.000 miners, one third of which coming from the Italian mainland;[39] most of them settled in Iglesias and frazioni .

At the end of the 19th century, communities of fishermen from Sicily, Torre del Greco (Campania) and Ponza (Lazio) migrated on the east coasts of the island, in the towns of Arbatax/Tortolì, Siniscola and La Maddalena.

In the 20th century, a large immigration flow from the Italian peninsula during the Fascist period occurred, as a result of a government policy: a number of people hailing from Veneto but also from Marche, Abruzzo and Sicily came to Sardinia to populate the island, especially the new mining town of Carbonia and the villages of Mussolinia di Sardegna (now Arborea) and Fertilia; besides, after World War II, Istrian Italian refugees were relocated in the Nurra region, along the north-west coastline. Today Istriot, Venetian and Friulan are spoken by the elderly in Fertilia, Tanca Marchese and Arborea.[40] In the same period, few Italian Tunisian families settled in the sparsely populated area of Castiadas, east of Cagliari.[41]

Following the Italian economic miracle, a historic migratory movement from the inland to the coastal and urban areas of Cagliari, Sassari-Alghero-Porto Torres and Olbia, which today collect most of the people, took place.

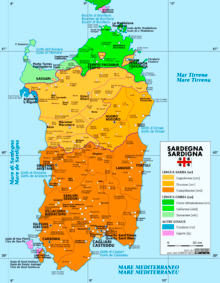

Demographics

With a population density of 69/km2, slightly more than a third of the national average, Sardinia is the fourth least populated region in Italy. The population distribution is anomalous compared to that of other Italian regions lying on the sea. In fact, contrary to the general trend, urban settlement has not taken place primarily along the coast but towards the centre of the island. Historical reasons for this include repeated Moorish raids during the Middle Ages (making the coast unsafe), widespread pastoral activities inland, and the swampy nature of the coastal plains (reclaimed only in the 20th century). The situation has been reversed with the expansion of seaside tourism; today all Sardinia's major urban centres are located near the coasts, while the island's interior is very sparsely populated.

It is the region of Italy with the lowest total fertility rate[42][43] (1.087 births per woman), and the region with the second-lowest birth rate;[44] The Sardinian fertility rate is actually the lowest in the world.[45] However, the population in Sardinia has increased in recent years because of massive immigration, mainly from the Italian mainland, but also from Eastern Europe (esp. Romania), Africa and China.

As of 2013, there were 42.159 foreign (that is, any people who have not applied for Italian citizenship) national residents, forming 2.5% of the total population.[46]

Age expectancy and Longevity

Average life expectancy is slightly over 82 years (85 for women and 79.7 for men[47]).

Sardinia is the first discovered Blue Zone, a demographic and/or geographic area of the world where people live measurably longer lives.[48] Sardinians share with the Ryukyuans from Okinawa[49][50] (Japan) the highest rate of centenarians in the world (22 centenarians/100,000 inhabitants). The key factors of such a high concentration of centenarians are identified in the genetics of the Sardinians,[51][52][53] lifestyle such as diet and nutrition, and the social structure.[54]

Demographic indicators

- Birth Rate: 8.3 (per 1,000 inhabitants – 2005) [55]

- Fertility Rate: 1.07 (births per woman – 2005) [56]

- Mortality rate: 8.7 (per 1,000 inhabitants – 2005) [55]

- Infant mortality rate males: 4.6 (per 1,000 births- 2000) [57]

- Infant mortality rate females: 3.0 (per 1,000 births – 2000) [57]

- Marriage rate: 2.9 (per 1,000 inhabitants – 2014) [58]

- Suicide rate: 22.65 (per 100,000 inhabitants)[59]

- Total literacy rate: 98.2%[60][61]

- Literacy rate under 65 years old: 99.5%[60][61]

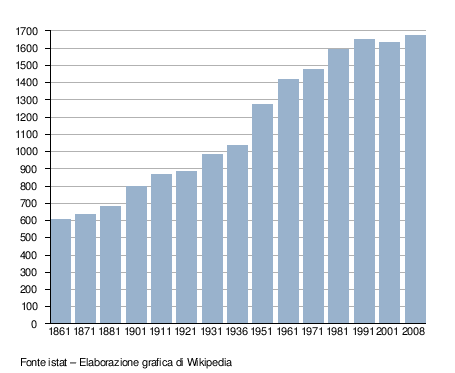

Historical population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1485 | 157,578 | — |

| 1603 | 266,676 | +69.2% |

| 1678 | 299,356 | +12.3% |

| 1688 | 229,532 | −23.3% |

| 1698 | 259,157 | +12.9% |

| 1728 | 311,902 | +20.4% |

| 1751 | 360,805 | +15.7% |

| 1771 | 360,785 | −0.0% |

| 1776 | 422,647 | +17.1% |

| 1781 | 431,897 | +2.2% |

| 1821 | 461,931 | +7.0% |

| 1824 | 469,831 | +1.7% |

| 1838 | 525,485 | +11.8% |

| 1844 | 544,253 | +3.6% |

| 1848 | 554,717 | +1.9% |

| 1857 | 573,243 | +3.3% |

| 1861 | 609,000 | +6.2% |

| 1871 | 636,000 | +4.4% |

| 1881 | 680,000 | +6.9% |

| 1901 | 796,000 | +17.1% |

| 1911 | 868,000 | +9.0% |

| 1921 | 885,000 | +2.0% |

| 1931 | 984,000 | +11.2% |

| 1936 | 1,034,000 | +5.1% |

| 1951 | 1,276,000 | +23.4% |

| 1961 | 1,419,000 | +11.2% |

| 1971 | 1,474,000 | +3.9% |

| 1981 | 1,594,000 | +8.1% |

| 1991 | 1,648,000 | +3.4% |

| 2001 | 1,632,000 | −1.0% |

| 2011 | 1,639,362 | +0.5% |

| Source: ISTAT 2011, – D.Angioni-S.Loi-G.Puggioni, La popolazione dei comuni sardi dal 1688 al 1991, CUEC, Cagliari, 1997 – F. Corridore, Storia documentata della popolazione di Sardegna, Carlo Clausen, Torino, 1902 | ||

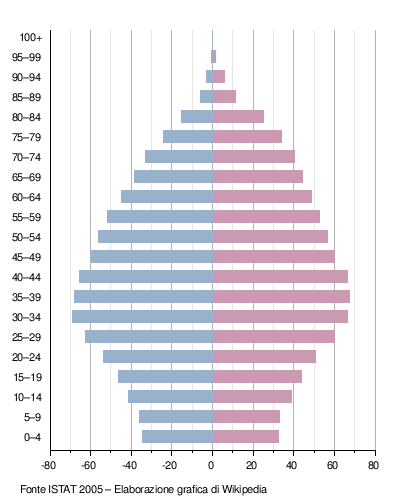

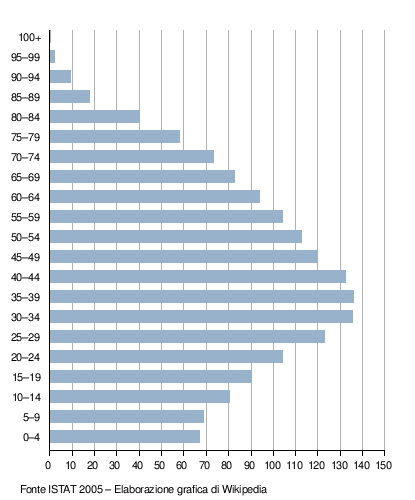

Division by gender and age

Total population by age

Geographical distribution

Most Sardinians are native to the island but a sizable number of people have settled outside Sardinia: it had been estimated that, between 1955 and 1971, 308,000 Sardinians have emigrated to the Italian mainland.[62] Sizable Sardinian communities are located in Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy, Tuscany and Latium.

Sardinians and their descendants are also numerous in Germany, France, Belgium, Switzerland. Almost all the Sardinians migrating to the Americas settled down in the Southern part of the continent, especially in Argentina (between 1900 and 1913 about 12,000 Sardinians lived in Buenos Aires and neighbourhoods)[63] and Uruguay (in Montevideo in the 1870s lived 12,500 Sardinians). Between 1876 and 1903, 92% of the Sardinians that moved towards the Americas settled in Brazil.[64] Between 1876 and 1925 34,190 Sardinians migrated to Africa, in particular towards the then French Algeria and Tunisia.[64] Small communities with Sardinians ancestors, about 5000 people, are also found in Brazil (mostly in the cities of Belo Horizonte, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo),[65] the UK and Australia.

The Region of Sardinia keeps a register of overseas Sardinians that managed to set up, in the Italian mainland and the rest of the world, a number of cultural associations: these are meant to provide the people of Sardinian descent, or those with an interest on Sardinian culture, an opportunity to enjoy a wide range of activities. As of 2012, there are 145 clubs registered on it.[66]

| Sardinians residing in European countries 2008[67] | |

| Germany | 27,184 |

| France | 23,110 |

| Belgium | 12,126 |

| Switzerland | 7,274 |

| Netherlands | 6,040 |

| Others | 17,763 |

| Total | 93,497 |

Unlike the rest of Italian emigration, where migrants were mainly males, between 1953–1974 an equal number of females and males emigrated from Sardinia to the Italian mainland.

Surnames and given names

The most common Sardinian surnames, like Sanna (fang), Piras (pears), Pinna (feather, pen) and Melis (honey),[68][69] derive from the Sardinian language and developed in the Middle Ages as a result of being registered in documents like the condaghes for administrative purposes; most of them derive either from Sardinian place names (e.g. Fonnesu "from Fonni",[70] Busincu "from Bosa" etc.), from animal names (e.g. Porcu "pig", Piga "magpie", Cadeddu "puppy" etc.) or from a person's occupation, nickname (e.g. Pittau "Sebastian"[71]), distinctive trait (e.g. Mannu "big"), and filiation (last names ending in -eddu which could stand for "son of", e.g. Corbeddu "son/daughter of Corbu"[71]). Some local surnames also derive from terms of the Paleo-Sardinian substrate.[70] The largest percentage of last names originating from outside the island is Corsican,[72] followed by Italian and Spanish (especially Catalan) surnames.

| Most common surnames | |

| 1 | Sanna |

| 2 | Piras |

| 3 | Pinna |

| 4 | Serra |

| 5 | Melis |

| 6 | Carta |

| 7 | Manca |

| 8 | Meloni |

| 9 | Mura |

| 10 | Lai |

| 11 | Murgia |

| 12 | Porcu |

| 13 | Cossu |

| 14 | Usai |

| 15 | Loi |

| 16 | Marras |

| 17 | Floris |

| 18 | Deiana |

| 19 | Cocco |

| 20 | Fadda |

As to what pertains to given names, the most widespread on the island are now the Italian ones. Nevertheless, a number of Sardinian-specific personal names is historically attested and they were prevalent among the islanders up until the contemporary era.

Culture

Languages

Alongside Italian (Italiano) that, once first introduced in the island by law in July 1760,[73][74] became the official language of the Piedmontese Kingdom at the expense of Spanish and Catalan, Sardinian (su sardu)[6][75] is the other most widely spoken language of the island and has also been the historical language of indigenous Sards,[76][77] ever since Latin supplanted the old Paleo-Sardinian. However, because of a rather rigid model of Italian education system that strongly discouraged the Sardinian youth from learning and speaking their language,[78] the numbers of people retaining Sardinian have gradually become a minority in their own island, giving way to a regional variety of Italian instead. As a result of that, Sardinian is currently facing challenges analogue to other minority languages across Europe,[79] and both the Logudorese and Campidanese dialects (the main varieties of Sardinian) have been designated as definitely endangered by UNESCO.[80] The other languages spoken on Sardinia, all also endangered but with much fewer speakers than Sardinian, are not indigenous to the island but developed after the settlement of certain ethnic communities, namely Corsicans, Catalans and Genoese, in different regions of the island over recent centuries; these include Sassarese (Sassaresu),[81] Gallurese (Gadduresu),[82] Algherese Catalan (Alguerés),[83] and Ligurian Tabarchino (Tabarchin).[84]

Flag

The so-called flag of the Four Moors is the historical and official flag of Sardinia. The flag is composed of the St George's Cross and four Moor's heads wearing a white bandana in each quarter. Its origins are basically shrouded in mystery, but it is presumed it originated in Aragon to symbolize the defeat of the Saracen invaders in the battle of Alcoraz.[85]

Sardinia's Day

Sardinia's Say (Sa die de sa Sardigna in Sardinian) is a holiday celebrated each 28 April to commemorate the revolt occurring from 1794 to 1796 against the feudal privileges, and the execution or expulsion of the Savoyard officials (including the Piedmontese viceroy, Balbiano) from Sardinia on 28 April 1794. The rebellion was spurred by the King's refusal to grant the island the autonomy the locals demanded in exchange for defeating the French.[86][87][88] The holiday has been formally recognised by the Sardinian Council since 14 September 1993.[89] Some public events are annually held to commemorate the episode, while the schools are closed.

Religion

The vast majority of the Sardinians are baptized as Roman Catholic, however church attendance is one of the lowest in Italy (21.9%).[90] Our Lady of Bonaria is the Patroness Saint of Sardinia.

Traditional clothes

Colourful and of various and original forms, the Sardinian traditional clothes are a clear symbol of belonging to specific collective identities. Although the basic model is homogeneous and common throughout the island, each town or village has its own traditional clothing which differentiates it from the others.

In the past, the clothes diversified themselves even within the communities, performing a specific function of communication as it made it immediately clear the marital status and the role of each member in the social area. Until the mid-20th century the traditional costume represented the everyday clothing in most of Sardinia, but even today in various parts of the island it is possible to meet elderly people dressed in costume.

The materials used for their packaging are among the most varied, ranging from the typical Sardinian woollen fabric (orbace) to silk and from linen to leather. The various components of the feminine apparel are: the headgear (mucadore), the shirt (camisa), the bodice (palas, cossu), the jacket (coritu, gipone), the skirt (unnedda, sauciu), the apron (farda, antalena, defentale). Those of the male are: the headdress (berritta), the shirt (bentone or camisa), the jacket (gipone), the trousers (cartzones or bragas), the skirt (ragas or bragotis), the overcoat (gabbanu, colletu) and the mastruca, a sort of sheep or lamb leather jacket without sleeves ("mastrucati latrones" or "thieves with rough wool cloaks" was the name by which Cicero denigrated the Sardinians who rebelled against the Roman power).

Genetics

Sardinians, while being part of the European gene pool, are outliers in the European genetic landscape[91] (together with the Basques, the Sami and the Icelanders[92]) in part because of particular phenomena that are often found in isolated populations, such as the founder effect and the genetic drift. The data seem to suggest that the current population is derived in large part from the Stone age settlers,[51] with some other minor contributions in the Chalcolithic and the early Bronze age; the contribution, in terms of gene flow, of the historical colonizers appears in fact to be very scarce.[93][94] The researchers found the Basques to be the genetically closest population to the Sardinians, and that such similarity is not mediated by the influence of other Spaniards in modern times.[3]

Recent comparisons between the Sardinians' genome and that of some individuals from the Neolithic and the early Chalcolithic, who lived in the Alpine (Oetzi), German, and Hungarian regions, showed considerable similarities between the two populations, while at the same time consistent differences between the prehistoric samples and the present inhabitants of the same geographical areas were noted.[95] From this it can be deduced that, while central and northern Europe have undergone significant demographic changes due to post-Neolithic migrations, presumably from the eastern periphery of Europe (Pontic-Caspian steppe) and possibly from Scandinavia,[96] Southern Europe and Sardinia in particular were affected less; Sardinians appear to be the population that has best preserved the Neolithic legacy of Western Europe.[97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][95][105] A 2015 study estimated that roughly 84% of the Sardinian ancestry derives from the Neolithic Europeans (a hybrid population of Mesolithic Europeans and Anatolian farmers), while the remaining 16% derives from Late Neolithic/Bronze age Central Europeans (Neolithic Europeans mixed with steppe pastoralists).[103]:119

However, Sardinians as a whole are not a homogeneous population genetically: some studies have found some differences among the various villages of the island;[106] in this regard, the mountainous area of Ogliastra (part of the wider region of Barbagia) is more distant from the rest of Europe and the Mediterranean than other Sardinian sub-regions located in the plains and in the coastal areas,[107] in part because these more accessible areas show, like the rest of much of Europe, a moderate genetic influx from the Yamna culture pastoralists, thought to be the carriers of Indo-European languages into Europe, while Ogliastra has retained unaltered Mesolithic/Neolithic roots.[108]

According to a study released in 2014, the genetic diversity among some Sardinian individuals from different regions of the island is between 7 and 30 times higher than the one found among other European ethnicities living thousands kilometers away from each other, like Spaniards and Romanians.[109] A similar phenomenon is common to some other isolated populations, like the Ladin groups living in Veneto and the Alpine area,[110][111] where the regional orography negatively affected the amount of interactions among each other.

However, while a very high degree of interindividual genetic differentiation has been detected on multiple occasions, other studies have also stated that such variability does not occur among the main macro-regions of the island: a Sardinian region like the Barbagia has been proven not to be significantly different from the regions on the coast, like the area of Cagliari and Oristano.[94] Another study, based on the multinomial logistic regression model, suggested again a high degree of homogeneity within the Sardinian population.[112]

The SardiNIA study in 2015 showed, by using the FST differentiation statistic, a clear genetic differentiation between Sardinians (whole genome sequence of 2120 individuals from across the island and especially the Lanusei valley) and mainland Italian populations (1000 genomes), and reported an even greater difference between Sardinians from the Lanusei valley and other European populations. This pattern of differentiation is also evident in the lengths for haplotypes surrounding rare variants loci, with a similar haplotype length for Sardinian populations and shorter length for populations with low grade of common ancestry.[113]

Notable Sardinians

Gallery

- Sardinian traditional clothes and masks

Children from Ovodda

Children from Ovodda.jpg) Urthos mask of Fonni

Urthos mask of Fonni Robes from Maracalagonis

Robes from Maracalagonis Woman from Ollolai

Woman from Ollolai Robes from Cagliari

Robes from Cagliari Robes from Busachi

Robes from Busachi- Robes from Olbia

Robe from Sennori

Robe from Sennori Robe from Oristano

Robe from Oristano Daily traditional clothe from Dorgali

Daily traditional clothe from Dorgali Folk robes from Quartu Sant'Elena

Folk robes from Quartu Sant'Elena Robes from Selargius

Robes from Selargius- Robes from Assemini

- Child from Aritzo

Women dressed in traditional Sardinian clothing (Selargius)

Women dressed in traditional Sardinian clothing (Selargius) Robes from Settimo San Pietro

Robes from Settimo San Pietro Robe from Dolianova

Robe from Dolianova Robe from Nuragus

Robe from Nuragus Knights from Teulada

Knights from Teulada Traditional robe from Laconi

Traditional robe from Laconi Robe from Tonara

Robe from Tonara.jpg) Robes from Fonni

Robes from Fonni A Mamuthone and an Issohadore, traditional carnival garments from Mamoiada

A Mamuthone and an Issohadore, traditional carnival garments from Mamoiada Sardinian knights on Sa Sartiglia day (Oristano).

Sardinian knights on Sa Sartiglia day (Oristano)..jpg) People in traditional dress (Busachi)

People in traditional dress (Busachi) Robe from Orgosolo

Robe from Orgosolo Robe from Florinas

Robe from Florinas People from Cagliari

People from Cagliari Sardinian men and children in traditional dress at the Sagra del Redentore (Nuoro)

Sardinian men and children in traditional dress at the Sagra del Redentore (Nuoro)- Children from Ovodda in traditional dress

An Issohadore, typical mask of the Sardinian carnival (Mamoiada)

An Issohadore, typical mask of the Sardinian carnival (Mamoiada) A Mamuthone, another typical mask of the Sardinian carnival (Mamoiada)

A Mamuthone, another typical mask of the Sardinian carnival (Mamoiada) Boe and Merdule (Ottana)

Boe and Merdule (Ottana) Mask of Sartiglia

Mask of Sartiglia Sardinians in traditional dress (Orgosolo)

Sardinians in traditional dress (Orgosolo) Robe from Atzara

Robe from Atzara Robe from Oliena

Robe from Oliena- Robe from Orune

- Man from Austis

Robe from Ittiri

Robe from Ittiri Robe from Sassari

Robe from Sassari Sardinian man in traditional dress playing the Launeddas

Sardinian man in traditional dress playing the Launeddas Robe from Cossoine

Robe from Cossoine Robe from Isili

Robe from Isili

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Sardinia. |

References

- Historia de la isla de Cerdeña, por el caballero G. de Gregory, traducida al castellano por una sociedad literaria (1840). Barcelona: Imprenta de Guardia Nacional.

- Gonen, Amiram (1996). Diccionario de los pueblos del mundo. Anaya&Mario Muchnik.

- Casula, Francesco Cesare (1994). La Storia di Sardegna. Sassari: Carlo Delfino Editore.

- Brigaglia, Manlio; Giuseppina Fois; Laura Galoppini; Attilio Mastino; Antonello Mattone; Guido Melis; Piero Sanna; Giuseppe Tanda (1995). Storia della Sardegna. Sassari: Soter Editore.

- Perra, Mario (1997). ΣΑΡΔΩ, Sardinia, Sardegna (3 Volumes). Oristano: S'Alvure.

- Ugas, Giovanni (2006). L'Alba dei Nuraghi. Cagliari: Fabula Editore. ISBN 978-88-89661-00-0.

- Cole, Jeffrey (2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe: an Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-302-6.

- Danver, Steven Laurence. Native peoples of the world: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures, and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. ISBN 0765682222. .

- Contu, Ercole (2014). I sardi sono diversi. Carlo Delfino Editore.

- Onnis, Omar (2015). La Sardegna e i sardi nel tempo. Arkadia Editore.

Notes

- ↑ Statistiche demografiche ISTAT

- ↑ Sardinia, Lonely Planet, Damien Simonis

- 1 2 Genomic history of the Sardinian population, Nature

- ↑ G. Vona, P. Moral, M. Memmì, M.E. Ghiani and L. Varesi, Genetic structure and affinities of the Corsican population (France): Classical genetic markers analysis, American Journal of Human Biology; Volume 15, Issue 2, pages 151–163, March/April 2003

- ↑ Grimaldi MC, Crouau-Roy B, Amoros JP, Cambon-Thomsen A, Carcassi C, Orru S, Viader C, Contu L. - West Mediterranean islands (Corsica, Balearic islands, Sardinia) and the Basque population: contribution of HLA class I molecular markers to their evolutionary history.

- 1 2 Sardinians – World Directory of Minorities

- ↑ Sard. Oxford Dictionary.

- ↑ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 776. ISBN 0313309841.

Romance (Latin) nations...

- ↑ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 588. ISBN 0313309841.

The Sards are a Romance people, the descendants of early Latins and later admixtures of the island's many conquerors.

- ↑ Danver, Steven L. Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues, pp.370-371

- ↑ Lang, Peter; Petricioli, Marta. L’Europe Méditerranéenne, pp.201-254,

- ↑ Edelsward, Lisa-Marlene; Salzman, Philip (1996). Sardinians - Encyclopedia of World Cultures

- ↑ Cole, Jeffrey. Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, pp.321-325

- ↑ La stele di Nora contiene la lingua sarda delle origini, Salvatore Dedola

- ↑ Platonis dialogi, scholia in Timaeum (edit. C. F. Hermann, Lipsia 1877), 25 B, pag. 368

- ↑ M. Pittau, La Lingua dei Sardi Nuragici e degli Etruschi, Sassari 1981, pag. 57

- ↑ Personaggi: Sardo

- ↑ Sardi in Dizionario di Storia (2011), Treccani

- ↑ Sardi in Enciclopedia Italiana (1936), Giacomo Devoto, Treccani

- ↑ Nuovo studio dell’archeologo Ugas: “È certo, i nuragici erano gli Shardana”

- ↑ Shardana, sardi nuragici: erano lo stesso popolo?, Interview with Giovanni Ugas (in Italian)

- ↑ Manlio Brigaglia – Storia della Sardegna, pg. 48-49-50

- ↑ Giovanni Ugas – L'alba dei Nuraghi , pg.22-23-24

- ↑ Giovanni Ugas – L'alba dei Nuraghi, p. 241

- ↑ SardiniaPoint.it – Interview with Giovanni Ugas, archaeologist and professor of the University of Cagliari (in Italian)

- ↑ Giovanni Ugas - L'Alba dei Nuraghi pg.241,254 - Cagliari, 2005

- ↑ Contini & Tuttle, 1982: 171; Blasco Ferrer, 1989: 14.

- ↑ Story of Language, Mario Pei, 1949

- ↑ Romance Languages: A Historical Introduction, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ A. Mastino, Storia della Sardegna antica, p.173

- ↑ Francesco Cesare Casula – La Storia di Sardegna, pg.141

- ↑ Manlio Brigaglia – Storia della Sardegna , pg.158

- ↑ Minority Rights Group International – Sardinians

- ↑ Stranieri nella Cagliari del XVI e XVII secolo da "Los Otros: genti, culture e religioni diverse nella Sardegna spagnola”, Cagliari, 23 aprile 2004.

- ↑ Antonio Budruni, Da vila a ciutat: aspetti di vita sociale in Alghero, nei secoli XVI e XVII

- 1 2 3 Carlo Maxia, Studi Sardo-Corsi, Dialettologia e storia della lingua fra le due isole

- ↑ Stefano Musso, Tra fabbrica e società: mondi operai nell'Italia del Novecento, Volume 33, p.316

- ↑ Quando i bergamaschi occuparono le case Archived 12 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Il progresso sociale della Sardegna e lo sfruttamento industriale delle miniere – Sardegnaminiere.it

- ↑ Veneti nel Mondo (Venetians in the World) – Anno III – numero 1 – Gennaio 1999 (in Italian)

- ↑ E al ritorno conquistarono le terre abbandonate – La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ ISTAT Numero medio di figli per donna per regione 2002–2005

- ↑ Solo 1,1 figli per madre, la Sardegna ultima in Italia - La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ ISTAT Tassi generici di natalità, mortalità e nuzialità per regione 2002–2005

- ↑ Fertilità, Sardegna ultima al mondo - Sardinian socio-economic Observatory

- ↑ Rapporto Istat – La popolazione straniera residente in Italia al 31º dicembre 2013

- ↑ ISTAT - INDICATORI DEMOGRAFICI anno 2015- page 6

- ↑ Sardinia, Italy – Blue Zones

- ↑ Okinawa Exploration Backgrounds – Blue Zones

- ↑ Does Sardinia hold the secret of long life - mystery, The Guardian

- 1 2 Francesco Cucca: “Caratteri immutati da diecimila anni, ecco perché la Sardegna è speciale” (di Elena Dusi) - Sardegna Soprattutto

- ↑ Sardinia Exploration Backgrounds – Blue Zones

- ↑ Polidori MC, Mariani E, Baggio G, et al. (Jul 2007). "Different antioxidant profiles in Italian centenarians: the Sardinian peculiarity". Eur J Clin Nutr. 61 (7): 922–4. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602596. PMID 17228351.

- ↑ Susan Pinker: why face-to-face contact matters in our digital age – The Guardian

- 1 2 ISTAT Tassi generici di natalità, mortalità e nuzialità per regione 2002–2005

- ↑ ISTAT Numero medio di figli per donna per regione 2002–2005

- 1 2 Ministero della Salute Speranza di vita e mortalità Archived 20 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Matrimoni, Il processo di secolarizzazione in Sardegna - Sardinian Socio-Economic Observatory

- ↑ Isola prima in Italia per suicidi, Ansa.it

- 1 2 Analfabetismo Italia – Censimento 2001

- 1 2 Sardegna Statistiche: Analfabeti

- ↑ Giuseppe Sanna – L'emigrazione della Sardegna (Emigration of Sardinia) (in Italian)

- ↑ L'emigrazione sarda tra la fine dell' 800 e i primi del 900

- 1 2 http://lipari.istat.it/digibib/Annuari/TO00176482Annuario_statistico_emigrazione_italiana_1876_1925.pdf Commissariato generale dell'emigrazione (a cura di), Annuario statistico della emigrazione italiana dal 1876 al 1925

- ↑ Il messagero sardo – Una piccola ma attiva colonia di sardi vive nello stato di Bahia (in Italian)

- ↑

- ↑ Museo Nazionale Emigrazione Italiana – 25-03-2012

- ↑ I Sanna battono i Piras: è loro il cognome più diffuso in Sardegna. Ecco la classifica - La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ Cognomi | I più diffusi in Sardegna per territorio - Sardinian Socio-Economic Observatory

- 1 2 Rivista italiana di onomastica, Mauro Maxia, Cognomi sardi medioevali formati da toponimi

- 1 2 Pittau, Massimo, 2014. I cognomi della Sardegna: Significato e origine di 8.000 cognomi indigeni e forestieri, Ipazia Books

- ↑ Le origini dei cognomi sardi, dai colori agli animali, La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ Roberto Bolognesi, The phonology of Campidanian Sardinian : a unitary account of a self-organizing structure, The Hague : Holland Academic Graphics

- ↑ Amos Cardia, S'italianu in Sardìnnia, Iskra

- ↑ Sardinian is generally considered to be the most conservative Romance language, and was also the first language to split off genetically from the rest of the others, possibly as early as the 1st century BC. Sardinian is traditionally subdivided into two groups: the first one would be Logudorese (su sardu logudoresu) and the second one would be Campidanese (su sardu campidanesu).

- ↑ Danver, Steven. Native peoples of the world - An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures, and Contemporary Issues

- ↑ Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, ed. 2010. Paleosardo: Le radici linguistiche della Sardegna neolitica (Paleosardo: The Linguistic Roots of Neolithic Sardinian). De Gruyter Mouton

- ↑ Manuale di linguistica sarda (Manual of Sardinian linguistics), 2017, Ed. by Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, Peter Koch, Daniela Marzo. Manuals of Romance Linguistics, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.208

- ↑ Sardinia, Lonely Planet, Damien Simonis, pg. 44

- ↑ UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger

- ↑ It's a language born as a lingua franca of Tuscan-Corsican origin, with minor Ligurian, Catalan and Spanish influences and major Logudorese Sardinian influence.

- ↑ It's a Corsican dialect with Logudorese Sardinian influence.

- ↑ It's a Catalan dialect spoken in Alghero by the time Catalan invaders repopulated the town and expelled the indigenous population.

- ↑ It's a Ligurian dialect spoken in Carloforte and Calasetta.

- ↑ B. Fois, The crest of the four Moors, brief history of the Sardinian emblem, Carlo Delfino, Sassari 1990

- ↑ Alberto Loni e Giuliano Carta. Sa die de sa Sardigna - Storia di una giornata gloriosa. Sassari, Isola editrice, 2003.

- ↑ Massimo Pistis, Rivoluzionari in sottana. Ales sotto il vescovado di mons. Michele Aymerich, Roma, Albatros Il Filo, 2009.

- ↑ Adriano Bomboi, L'indipendentismo sardo. Le ragioni, la storia, i protagonisti, Cagliari, Condaghes, 2014.

- ↑ Sa die de sa Sardigna, Sardegna Cultura

- ↑ ISTAT

- ↑ Olivieri, A; Sidore, C; Achilli, A; Angius, A; Posth, C; Furtwängler, A; Brandini, S; Capodiferro, MR; Gandini, F; Zoledziewska, M; Pitzalis, M; Maschio, A; Busonero, F; Lai, L; Skeates, R; Gradoli, MG; Beckett, J; Marongiu, M; Mazzarello, V; Marongiu, P; Rubino, S; Rito, T; Macaulay, V; Semino, O; Pala, M; Abecasis, GR; Schlessinger, D; Conde-Sousa, E; Soares, P; Richards, MB; Cucca, F; Torroni, A (2017). "Mitogenome Diversity in Sardinians: A Genetic Window onto an Island's Past". Mol Biol Evol. 34: 1230–1239. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx082. PMC 5400395. PMID 28177087.

- ↑ Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, Alberto Piazza - The History and Geography of Human Genes, 1994, Princeton University Press, pp.272

- ↑ Franco Germanà, L'uomo in Sardegna dal paleolitico all'età nuragica p.202-206

- 1 2 Genetica, malattie e caratteri dei sardi, Francesco Cucca - Sardegna Ricerche

- 1 2 Genome flux and stasis in a five millennium transect of European prehistory

- ↑ Lazaridis et al., Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans p.10

- ↑ Keller at al 2011, Nature

- ↑ Mathieson et al 2015, Nature

- ↑ supp. info (p.16)

- ↑ A Common Genetic Origin for Early Farmers from Mediterranean Cardial and Central European LBK Cultures, Olalde et al 2015, Molecular Biology and Evolution

- ↑ Gamba et al 2014, Genome flux and stasis in a five millennium transect of European prehistory, Nature

- ↑ Omrak et al 2016, Genomic Evidence Establishes Anatolia as the Source of the European Neolithic Gene Pool, Current Biology, Volume 26, Issue 2, p270–275, 25 January 2016

- 1 2 Haak et al 2015, Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe

- ↑ supp. info (p.120)

- ↑ Reference Populations Genographic Project. National Geographic

- ↑ High Differentiation among Eight Villages in a Secluded Area of Sardinia Revealed by Genome-Wide High Density SNPs Analysis

- ↑ Genome-wide scan with nearly 700 000 SNPs in two Sardinian sub-populations suggests some regions as candidate targets for positive selection

- ↑ Chiang et al., Using whole-genome sequencing to shed insight on the complex prehistory of Sardinia

- ↑ Il Dna sardo è il più vario d'Europa Ricerca sugli abitanti di Benetutti – Unione Sarda

- ↑ Italiani, i più ricchi in Europa … di diversità genetica – Uniroma

- ↑ Gli italiani sono il popolo con la varietà genetica più ricca d'Europa – La Repubblica

- ↑ Di Gaetano, C; Fiorito, G; Ortu, MF; Rosa, F; Guarrera, S; Pardini, B; Cusi, D; Frau, F; Barlassina, C; Troffa, C; Argiolas, G; Zaninello, R; Fresu, G; Glorioso, N; Piazza, A; Matullo, G (2014). "Sardinians genetic background explained by runs of homozygosity and genomic regions under positive selection". PLoS One. 9: e91237. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091237. PMC 3961211. PMID 24651212.

- ↑ Sidore, C., y colaboradores (2015). "Genome sequencing elucidates Sardinian genetic architecture and augments association analyses for lipid and blood inflammatory markers". Nature Genetics. 47: 1272–1281. doi:10.1038/ng.3368. PMC 4627508. PMID 26366554.