Culture of Europe

The culture of Europe is rooted in the art, architecture, film, video games, different types of music, literature, and philosophy that originated from the continent of Europe.[1] European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".[2]

Definition

Because of the great number of perspectives which can be taken on the subject, it is impossible to form a single, all-embracing conception of European culture.[3] Nonetheless, there are core elements which are generally agreed upon as forming the cultural foundation of modern Europe.[4] One list of these elements given by K. Bochmann includes:[5]

- A common cultural and spiritual heritage derived from Greco-Roman antiquity, Christianity, Judaism, the Renaissance and its Humanism, the political thinking of the Enlightenment, and the French Revolution, and the developments of Modernity, including all types of socialism;[6][5]

- A rich and dynamic material culture that has been extended to the other continents as the result of industrialization and colonialism during the "Great Divergence";[6]

- A specific conception of the individual expressed by the existence of, and respect for, a legality that guarantees human rights and the liberty of the individual;[6]

- A plurality of states with different political orders, which are feeding each other with new ideas;[6]

- Respect for peoples, states and nations outside Europe.[6]

Berting says that these points fit with "Europe's most positive realisations".[7] The concept of European culture is generally linked to the classical definition of the Western world. In this definition, Western culture is the set of literary, scientific, political, artistic and philosophical principles which set it apart from other civilizations. Much of this set of traditions and knowledge is collected in the Western canon.[8] The term has come to apply to countries whose history has been strongly marked by European immigration or settlement during the 18th and 19th centuries, such as the Americas, and Australasia, and is not restricted to Europe..

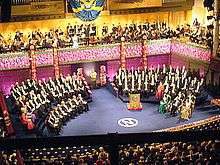

The Nobel Prize laureate in Literature Thomas Stearns Eliot in his 1948 book Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, credited the prominent Christian influence upon the European culture:[9] "It is in Christianity that our arts have developed; it is in Christianity that the laws of Europe have--until recently--been rooted."

Art

Prehistoric Art

Much surviving prehistoric art is small portable sculptures. It includes the oldest known representation of the human body, the Venus of Hohle Fel, dating from 40,000-35,000 BC, found in Schelklingen, Germany. It is part of a small group of female Venus figurines found in Central Europe. The Löwenmensch figurine, from about 30,000 BC, is the oldest undisputed piece of figurative art. The Swimming Reindeer of about 11,000 BCE is among the finest Magdalenian carvings in bone or antler of animals in the art of the Upper Paleolithic. At the beginning of the Mesolithic in Europe figurative sculpture greatly reduced, and remained a less common element in art than relief decoration of practical objects until the Roman period, despite some works such as the Gundestrup cauldron from the European Iron Age and the Bronze Age Trundholm sun chariot.

The oldest European cave art dates back 40,800, and can be found in the El Castillo Cave in Spain, but cave art exists across the continent. Rock painting was also performed on cliff faces, but fewer of those paintings have survived because of erosion. One well-known example is the rock paintings of Astuvansalmi in the Saimaa area of Finland.

The Rock art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin represents a very different style, with the human figure the main focus, often seen in large groups, with battles, dancing and hunting all represented, as well as other activities and details such as clothing. The figures are generally rather sketchily depicted in thin paint, with the relationships between the groups of humans and animals more carefully depicted than individual figures. The Iberian examples are believed to date from a long period perhaps covering the Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic and early Neolithic.

Prehistoric Celtic art comes from much of Iron Age Europe and survives mainly in the form of high-status metalwork skillfully decorated with complex, elegant and mostly abstract designs, often using curving and spiral forms. There are human heads and some fully represented animals, but full-length human figures of any size are so rare that their absence may represent a religious taboo. As the Romans conquered Celtic territories, it almost entirely vanishes, but the style continued in limited use in the British Isles, and with the coming of Christianity revived there in the Insular style of the Early Middle Ages.

Classical Art

Minoan art encompassed many media. Pottery was characterized by thin walled vessels, subtle, symmetrical shapes, elegant spouts, and decorations, and dynamic lines. Dark and light values were often contrasted in Minoan pottery. Early designs were spontaneous and fluid, with later ones becoming more stylized, and less naturalistic. The best known example of Minoan sculpture is the Snake Goddess figurine. The sculpture depicts a goddess or a high priestess holding a snake in both hands, dressed in traditional Minoan attire, cloth covering the whole body and leaving the breasts exposed. Exquisite metal work was also a characteristic of the Minoan art. Minoan metal masters worked with imported gold and copper and mastered techniques of wax casting, embossing, gilding, nielo, and granulation. Minoan painting was unique in that it used wet fresco techniques; it was characterized by small waists, fluidity, and vitality of the figures and was seasoned with elasticity, spontaneity, vitality, and high-contrasting colours.

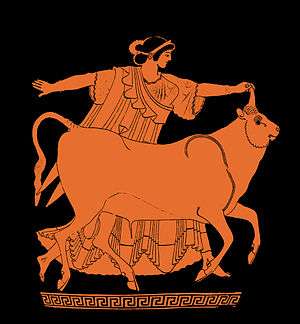

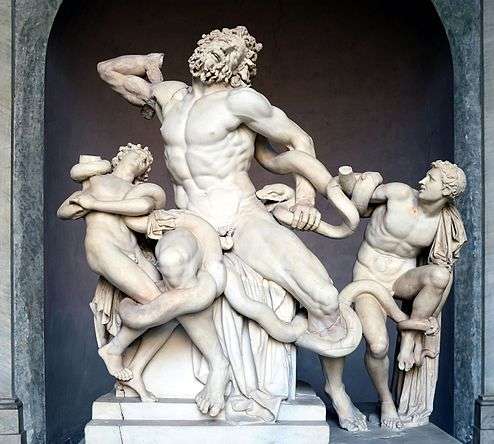

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery. Greek architecture, technically very simple, established a harmonious style with numerous detailed conventions that were largely adopted by Roman architecture and are still followed in some modern buildings. It used a vocabulary of ornament that was shared with pottery, metalwork and other media, and had an enormous influence on Eurasian art, especially after Buddhism carried it beyond the expanded Greek world created by Alexander the Great. The social context of Greek art included radical political developments and a great increase in prosperity; the equally impressive Greek achievements in philosophy, literature and other fields are well known.

Roman art was influenced by Greece and can in part be taken as a descendant of ancient Greek painting and sculpture, but was also strongly influenced by the more local Etruscan art of Italy. Sculpture was perhaps considered as the highest form of art by Romans, but figure painting was also very highly regarded. Roman sculpture is primarily portraiture derived from the upper classes of society as well as depictions of the gods. However, Roman painting does have important unique characteristics. Among surviving Roman paintings are wall paintings, many from villas in Campania, in Southern Italy, especially at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Such painting can be grouped into four main "styles" or periods and may contain the first examples of trompe-l'oeil, pseudo-perspective, and pure landscape.

Almost the only painted portraits surviving from the Ancient world are a large number of coffin-portraits of bust form found in the Late Antique cemetery of Al-Fayum. They give an idea of the quality that the finest ancient work must have had. A very small number of miniatures from Late Antique illustrated books also survive, and a rather larger number of copies of them from the Early Medieval period. Early Christian art grew out of Roman popular, and later Imperial, art and adapted its iconography from these sources.

Medieval Art

Byzantine art developed out of the art of the Roman Empire, which was itself profoundly influenced by ancient Greek art. Byzantine art never lost sight of this classical heritage. The Byzantine capital, Constantinople, was adorned with a large number of classical sculptures, although they eventually became an object of some puzzlement for its inhabitants. And indeed, the art produced during the Byzantine Empire, although marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, was above all marked by the development of a new, abstract, aesthetic, marked by anti-naturalism and a favour for symbolism.

The subject matter of monumental Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the two themes are often combined, as in the portraits of later Byzantine emperors that decorated the interior of the sixth-century church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. However, the Byzantines inherited the Early Christian distrust of monumental sculpture in religious art, and produced only reliefs, of which very few survivals are anything like life-size, in sharp contrast to the medieval art of the West, where monumental sculpture revived from Carolingian art onwards. Small ivories were also mostly in relief. The so-called "minor arts" were very important in Byzantine art and luxury items, including ivories carved in relief as formal presentation Consular diptychs or caskets such as the Veroli casket, hardstone carvings, enamels, glass, jewelry, metalwork, and figured silks were produced in large quantities throughout the Byzantine era.

Migration Period art includes the art of the Germanic tribes on the continent, as well the start of the Insular art or Hiberno-Saxon art of the Anglo-Saxonand Celtic fusion in the British Isles. It covers many different styles of art including the polychrome style and the animal style. After Christianization, Migration Period art developed into various schools of Early Medieval art in Western Europe which are normally classified by region, such as Anglo-Saxon art and Carolingian art, before the continent-wide styles of Romanesque art and finally Gothic art developed.

During the 2nd century the Goths of southern Russia discovered a newfound taste for gold figurines and objects inlaid with precious stones. This polychrome style was borrowed from Scythians and the Sarmatians, had some Greco-Roman influences, and was also popular with the Huns. Perhaps the most famous examples are found in the fourth-century Pietroasele treasure (Romania), which includes a great gold eagle brooch. The Animal Style first appeared in northwest Europe with the introduction of the chip carving technique applied to bronze and silver in the 5th century. It is characterized by animals whose bodies are divided into sections, and typically appear at the fringes of designs whose main emphasis is on abstract patterns. This was eventually supplanted by depictions of whole beasts, their bodies elongated into "ribbons" which intertwined into symmetrical shapes with no pretense of naturalism, rarely with legs, tending to be described as serpents—though heads often have characteristics of other animals.

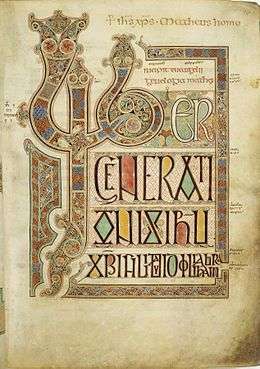

Insular art is the style of art produced in the post-Roman history of Ireland and Britain. The term derives from insula, the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style different from that of the rest of Europe. Surviving examples of Insular art are mainly illuminated manuscripts, metalwork and carvings in stone, especially stone crosses. Surfaces are highly decorated with intricate patterning, with no attempt to give an impression of depth, volume or recession. The best examples include the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels, Book of Durrow, brooches such as the Tara Brooch and the Ruthwell Cross. Carpet pages are a characteristic feature of Insular manuscripts, although historiated initials (an Insular invention), canon tables and figurative miniatures, especially Evangelist portraits, are also common.

Romanesque art is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic style in the 13th century, or later, depending on region. The term was invented by 19th-century art historians, especially for Romanesque architecture, which retained many basic features of Roman architectural style. The Romanesque style was the first style to spread across the whole of Catholic Europe, from Sicily to Scandinavia. Romanesque art was greatly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting, and by Insular art. From these elements was forged a highly innovative and coherent style. Art of the period was characterised by a very vigorous style in both sculpture and painting. The latter continued to follow essentially Byzantine iconographic models for the most common subjects in churches, which remained Christ in Majesty, the Last Judgement and scenes from the Life of Christ. In illuminated manuscripts, for which the most lavishly decorated manuscripts of the period were mostly bibles or psalters, more originality is seen, as new scenes needed to be depicted. The same applied to the capitals of columns, never more exciting than in this period, when they were often carved with complete scenes with several figures. The large wooden crucifix was a German innovation at the very start of the period, as were free-standing statues of the enthroned Madonna, but the high relief was above all the sculptural mode of the period.

Colours tended to be very striking, and mostly primary. Stained glass became widely used, although survivals are sadly few. Compositions usually had little depth, and needed to be flexible to be squeezed into the shapes of historiated initials, column capitals, and church tympanums; the tension between a tightly enclosing frame, from which the composition sometimes escapes, is a recurrent theme in Romanesque art. Figures often varied in size in relation to their importance, and landscape backgrounds, if attempted at all, were closer to abstract decorations than realism. Portraiture hardly existed.

Gothic art developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Southern and Central Europe, never quite effacing more classical styles in Italy. In the late 14th century, the sophisticated court style of International Gothic developed, which continued to evolve until the late 15th century. In many areas, especially Germany, Late Gothic art continued well into the 16th century, before being subsumed into Renaissance art. Primary media in the Gothic period included sculpture, panel painting, stained glass, fresco and illuminated manuscripts. The easily recognizable shifts in architecture from Romanesque to Gothic, and Gothic to Renaissance styles, are typically used to define the periods in art in all media, although in many ways figurative art developed at a different pace.

The earliest Gothic art was monumental sculpture, on the walls of Cathedrals and abbeys. Christian art was often typological in nature (see Medieval allegory), showing the stories of the New Testament and the Old Testament side by side. Saints' lives were often depicted. Images of the Virgin Mary changed from the Byzantine iconic form to a more human and affectionate mother, cuddling her infant, swaying from her hip, and showing the refined manners of a well-born aristocratic courtly lady.

Secular art came into its own during this period with the rise of cities, foundation of universities, increase in trade, the establishment of a money-based economy and the creation of a bourgeois class who could afford to patronize the arts and commission works resulting in a proliferation of paintings and illuminated manuscripts. Increased literacy and a growing body of secular vernacular literature encouraged the representation of secular themes in art. With the growth of cities, trade guilds were formed and artists were often required to be members of a painters' guild—as a result, because of better record keeping, more artists are known to us by name in this period than any previous; some artists were even so bold as to sign their names.

Renaissance Art

.jpg)

Renaissance art emerged as a distinct style in northern Italy from around 1420, in parallel with developments which occurred in philosophy, literature, music and science. It took as its foundation the art of Classical antiquity, but transformed that tradition by absorbing recent developments in the art of Northern Europe and by applying contemporary scientific knowledge. Renaissance artists painted a wide variety of themes. Religious altarpieces, fresco cycles, and small works for private devotion were very popular. For inspiration, painters in both Italy and northern Europe frequently turned to Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend (1260), a highly influential source book for the lives of saints that had already had a strong influence on Medieval artists. The rebirth of classical antiquity and Renaissance humanism also resulted in many Mythological and history paintings. Ovidian stories, for example, were very popular. Decorative ornament, often used in painted architectural elements, was especially influenced by classical Roman motifs.

Techniques characteristic of Renaissance art include the use of proportion and linear perspective; foreshortening, to create an illusion of depth; sfumato, a technique of softening of sharp outlines by subtle blending of tones to give the illusion of depth or three-dimensionality; and chiaroscuro, the effect of using a strong contrast between light and dark to give the illusion of depth or three-dimensionality.

Mannerism, Baroque and Rococo

Renaissance Classicism spawned two different movements—Mannerism and the Baroque. Mannerism, a reaction against the idealist perfection of Classicism, employed distortion of light and spatial frameworks in order to emphasize the emotional content of a painting and the emotions of the painter. Northern Mannerism took longer to develop, and was largely a movement of the last half of the 16th century. Where High Renaissance art emphasizes proportion, balance, and ideal beauty, Mannerism exaggerates such qualities, often resulting in compositions that are asymmetrical or unnaturally elegant. The style is notable for its intellectual sophistication as well as its artificial (as opposed to naturalistic) qualities. It favors compositional tension and instability rather than the balance and clarity of earlier Renaissance painting.

In contrast, Baroque art took the representationalism of the Renaissance to new heights, emphasizing detail, movement, lighting, and drama in their search for beauty. Perhaps the best known Baroque painters are Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, and Diego Velázquez. Baroque art is often seen as part of the Counter-Reformation—the artistic element of the revival of spiritual life in the Roman Catholic Church. Religious and political themes are widely explored within the Baroque artistic context, and both paintings and sculptures are characterised by a strong element of drama, emotion and theatricality. Baroque art was particularly ornate and elaborate in nature, often using rich, warm colours with dark undertones. Baroque art can be seen as a more elaborate and dramatic re-adaptation of late Renaissance art. Dutch Golden Age painting is a distinct subset of Baroque, leading to the development of secular genres such as still life, genre paintings of everyday scenes, and landscape painting.

By the 18th century, Baroque art was falling out of fashion as many deemed it too melodramatic and also gloomy, and it developed into the Rococo, which emerged in France. Rococo art was even more elaborate than the Baroque, but it was less serious and more playful. The artistic movement no longer placed an emphasis on politics and religion, focusing instead on lighter themes such as romance, celebration, and appreciation of nature. Furthermore, it sought inspiration from the artistic forms and ornamentation of Far Eastern Asia, resulting in the rise in favour of porcelain figurines and chinoiserie in general. Rococo soon fell out of favor, being seen by many as a gaudy and superficial movement emphasizing aesthetics over meaning. Neoclassicism in many ways developed as a counter movement of the Rococo, the impetus being a sense of disgust directed towards the latter's florid qualities.

Neoclassical, Romanticism, and Realism

Neoclassicism began in the 18th century as counter movement opposing the Rococo. It desired for a return to the simplicity, order and 'purism' of classical antiquity, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Neoclassicism was the artistic component of the intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment. Neoclassicism had become widespread in Europe throughout the 18th century, especially in the United Kingdom, which saw great works of Neoclassical architecture spring up during this period. In many ways, Neoclassicism can be seen as a political movement as well as an artistic and cultural one. Neoclassical art places an emphasis on order, symmetry and classical simplicity; common themes in Neoclassical art include courage and war, as were commonly explored in ancient Greek and Roman art. Ingres, Canova, and Jacques-Louis David are among the best-known neoclassicists.

Just as Mannerism rejected Classicism, Romanticism rejected the aesthetic of the Neoclassicists, specifically the highly objective and ordered nature of Neoclassicism, and opted for a more individual and emotional approach to the arts. Emphasis was placed on nature, especially when aiming to portray the power and beauty of the natural world, and emotions. Romantic art often used colours in order to express feelings and emotion. Similarly to Neoclassicism, Romantic art took much of its inspiration from ancient Greek and Roman art and mythology, yet, unlike Neoclassical, this inspiration was primarily used as a way to create symbolism and imagery. Romantic art also takes much of its aesthetic qualities from medievalism and Gothicism, as well as mythology and folklore. Among the greatest Romantic artists were Eugène Delacroix, Francisco Goya, J.M.W. Turner, John Constable, Caspar David Friedrich, Thomas Cole, and William Blake.

.jpg)

In response to these changes caused by Industrialisation, the movement of Realism emerged. Realism sought to accurately portray the conditions and hardships of the poor in the hopes of changing society. In contrast with Romanticism, which was essentially optimistic about mankind, Realism offered a stark vision of poverty and despair. Similarly, while Romanticism glorified nature, Realism portrayed life in the depths of an urban wasteland. Like Romanticism, Realism was a literary as well as an artistic movement. Other contemporary movements were more Historicist in nature, such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who attempted to return art to its state of "purity" prior to Raphael, and the Arts and Crafts Movement, which reacted against the impersonality of mass-produced goods and advocated a return to medieval craftsmanship.

Music

- Classical music: Important classical composers from Europe include: Hildegard von Bingen, J.S. Bach, Handel, Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, Wagner,

Richard Strauss, von Weber, Stockhausen, Mendelssohn, Pachelbel (Germany), Glinka, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninov, Scriabin, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, (Russia), Schubert, Haydn, Mozart, Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg, Strauss (Austria), Berlioz, Machaut, Pérotin, Couperin, Lully, Rameau, Offenbach, Saint-Saëns, Bizet, Debussy, Ravel, Satie (France), Palestrina, Monteverdi, Vivaldi, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Donizetti, Cavalli, Paganini, Bellini, Verdi, Puccini, Rossini (Italy), Tomás Luis de Victoria, Falla, Granados, Albéniz, Rodrigo (Spain), Smetana, Dvořák, Janáček, Martinů, Zelenka (Czechia), Dufay, des Prez, Lassus (Belgium), Sweelinck, Willem Pijper, Louis Andriessen (the Netherlands), Grieg (Norway), Liszt, Bartók (Hungary), Purcell, Elgar, Britten, Holst (UK), Nielsen (Denmark), Sibelius (Finland), Chopin, Penderecki (Poland), George Enescu, Sergiu Celibidache, Ciprian Porumbescu (Romania). Luciano Pavarotti was a contemporary popular opera singer.

Orchestras such as the Berliner Philharmoniker, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra and the London Symphony Orchestra are considered to be amongst the finest ensembles in the world. The Salzburg Festival, the Bayreuth Festival, the Edinburgh International Festival and the BBC Proms are major European classical music festivals, and International Chopin Piano Competition is the world's oldest monographic music competition.

- Folk music: Europe has a wide and diverse range of indigenous music, sharing common features in rural, travelling or maritime communities. Folk music is embedded in an unwritten, aural tradition, but was increasingly transcribed from the nineteenth century onwards. Many classical composers used folk melodies, and folk has influenced some popular music in Europe. See the list of European folk musics.

- Popular music: Europe has also imported many different genres of music, mainly from the United States, ranging from Blues, Jazz, Soul, Pop, Electronic, Hip-Hop, R'n'B or Dance and creating its own genres like Britpop, French hip-hop and others.

- United Kingdom: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Queen, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Elton John, David Bowie, Deep Purple, Sex Pistols, Eric Clapton, The Clash, Van Morrison, Dire Straits, The Police, Joy Division, Fleetwood Mac, Genesis, George Michael, Phil Collins, Rod Stewart, The Who, Rick Astley, Slick Rick, Eurythmics, Dusty Springfield, The Cure, Little Mix, Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, Judas Priest, Def Leppard, Duran Duran, Oasis, Radiohead, Coldplay, Mumford & Sons, Jax Jones, Rag'n'Bone Man, The Smiths, Stormzy, JP Cooper, Muse, Dizzee Rascal, Gorillaz, John Newman, Bonnie Tyler, Seal, Sigala, Elvis Costello, Calum Scott, James Arthur, Bee Gees, Spice Girls, Tinie Tempah, Depeche Mode, The Kinks, Jonas Blue, The Animals, Jess Glynne, Dua Lipa, Motörhead, UB40, Clean Bandit, Sam Smith, Texas, One Direction, Adele, Raye, Amy Winehouse, Charli XCX, Calvin Harris, Ellie Goulding, M.I.A., Anne Marie, Ed Sheeran, Skepta

- Ireland : U2, The Undertones, Paul Brady, Thin Lizzy, My Bloody Valentine, Niall Horan, Sinéad O'Connor, Primordial, Shane MacGowan, Danny O'Donoghue, The Cranberries

- France : Maurice Chevalier, Josephine Baker, Tino Rossi, Édith Piaf, Les Compagnons de la chanson, Yves Montand, Juliette Gréco, Barbara, Charles Aznavour, Georges Moustaki, Gilbert Bécaud, Guy Béart, Serge Gainsbourg, Léo Ferré, Charles Trenet, Georges Brassens, Jean Ferrat, Henri Salvador, Sacha Distel, Pierre Perret, Dalida, Claude François, Johnny Hallyday, Françoise Hardy, Jacques Dutronc, Mireille Mathieu, Claude Nougaro, Joe Dassin, Julien Clerc, Michel Sardou, Renaud, Francis Cabrel, Daniel Balavoine, Mylène Farmer, Vanessa Paradis, Willy William, Noir Désir, Daft Punk, David Guetta, Indila, Justice, Bob Sinclar, Martin Solveig, Étienne de Crécy, Fatal Bazooka, M83, C2C, Jean Michel Jarre, Gojira, Soprano, Black M, Maître Gims, Kendji Girac, Lartiste

- Portugal : Amália Rodrigues, The Legendary Tigerman, The Gift, Moonspell, Agir, Diego Miranda, Ana Free, David Carreira, Diogo Piçarra

- Denmark : Gasolin, DAD (Disneyland After Dark), Magtens Korridorer, Rasmus Seebach, The Raveonettes, Agnes Obel, WhoMadeWho, Lukas Graham, MØ

- Finland : HIM, The Rasmus, Nightwish, Korpiklaani, Ensiferum, Alma, Lordi

- Germany : Kraftwerk, Scorpions, Tangerine Dream, Neu!, Rammstein, Lena, Paul Kalkbrenner, Accept, ATB, Robin Schulz, Alle Farben, Nina Hagen, MoTrip, Michael Mind Project, Sarah Connor, Xavier Naidoo, Johannes Oerding, Max Giesinger, Yvonne Catterfeld, Anna Naklab, Wincent Weiss, Adel Tawil, Samy Deluxe, Modern Talking, Kool Savas, Azad, Marteria, Capital Bra, Gzuz, Namika, Alphaville, Powerwolf, Bonez MC, Paul van Dyk, Alice Merton, Nico Santos, RAF Camora, Eko Fresh, Bushido, Cascada, Mark Forster, Felix Jaehn, Lou Bega, Farid Bang, Sandra, Zedd, Scooter, Alex C, Kay One, Bausa

- Italy : Giorgio Moroder, Andrea Bocelli, Ennio Morricone, Benny Benassi, Mina, Laura Pausini, Zucchero Fornaciari, Eros Ramazzotti, Tiziano Ferro, Luciano Pavarotti, Enrico Caruso, Alessandro Bonci, Al Bano and Romina Power, Adriano Celentano, Raffaella Carrà, Toto Cutugno, Fabrizio De André, Francesco De Gregori, Lucio Battisti, Domenico Modugno, Patty Pravo, Umberto Tozzi, Milva, Jovanotti, Elisa, Giorgia, Chiara Galiazzo, Emma Marrone, Pino Daniele, Francesca Michielin, Marco Mengoni, Francesco Gabbani, Eiffel 65, Gabry Ponte, Robert Miles, Nek, J-Ax, Fedez, Alex Gaudino, Tacabro, Merk & Kremont, Gigi D'Agostino, Baby K, Ermal Meta, Fabrizio Moro, Sfera Ebbasta, Ghali, Il Volo, Area, PFM, Banco del Mutuo Soccorso, Le Orme, Goblin, Pooh, Fleshgod Apocalypse, Rhapsody of Fire, Lacuna Coil

.jpg)

- Poland : Doda, Cleo, Dawid Kwiatkowski, Tede, Donatan, Michał Szpak, Margaret, Popek, Peja, Sokół, Behemoth, Natalia Nykiel, Ewelina Lisowska, Monika Lewczuk, Gromee, C-BooL

- Romania : Alexandra Stan, Inna, Edward Maya, Akcent, Elena, Sarmalele Reci, Negură Bunget, Transsylvania Phoenix, Fly Project, G Girls, Tom Boxer, Sandu Ciorba, Morandi

- Ukraine : Ruslana, Jamala, Pianoboy, Alekseev, Monatik, TNMK, Seryoga, Yarmak

- Greece : Vangelis, Demis Roussos, Helena Paparizou, Nana Mouskouri

- Russia : Eduard Artemyev, Eduard Khil, Kino, Filatov & Karas, Gamora, Mumiy Troll, Leningrad, Zemfira, t.A.T.u., Oxxxymiron, Egor Kreed, Svoy, Serebro, Nyusha, Lesya Yaroslavskaya, Irina Dubtsova, Anna Semenovich, PPK, Dima Bilan, Aria, Vremya i Steklo, Aleksandr Revva, Timati, Ligalize, Jacques Anthony, Allj, L'One, Bogdan Titomir, ST1M, Gorky Park, Algie & Kravtsov, Sergey Lazarev, Detsl, Feduk

- Others : Julio Iglesias, Enrique Iglesias (Spain), Björk, Sigur RósLepa Brena, Sólstafir (Iceland), Sigrid (Norway), Helena Vondráčková (Czech Republic), Kati Wolf (Hungary), Basta (Russia), Edyta Gorniak (Poland), Bijelo Dugme (Yugoslavia), Gaitana (Ukraine), Sólstafir (Iceland), Eluveitie (Switzerland), a-ha (Norway), Mike Candys (Switzerland), Sak Noel (Spain), Jacques Brel, Stromae (France), Soulwax (Belgium), Týr (Faroe Islands), Rytmus (Slovakia), Erben der Schöpfung (Liechtenstein), Ektor (Czech Republic), VovaZIL’Vova (Ukraine), Metsatöll (Estonia), Irfan (Bulgaria), Dynoro (Lithuania), Mahmut Orhan (Turkey), Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike (Belgium), Alan Walker (Norway), Kygo (Norway), DJ Snake (France), Lost Frequencies (Belgium), Álvaro Soler (Spain), Era Istrefi (Kosovo)

- Other music: Anthem of Europe, Champions League Anthem, Nations League Anthem

- Main festivals includes: Sanremo Music Festival (Italy), Coca-Cola Summer Festival (Italy), Glastonbury (UK), Reading and Leeds Festivals, Isle of Wight Festival (UK), T in the Park (UK), Fête de la Musique, Rock en Seine (France), Eurockéennes, Vieilles Charrues Festival, Hellfest (France), Wacken (Germany), Festival Internacional de Benicàssim, Ultra Europe (Croatia), Primavera Sound (Spain), Exit Festival (Serbia), Open'er Festival (Poland), Sziget Festival (Hungary), Roskilde Festival (Denmark), Kilkim Žaibu (Baltic region) Rock Werchter, Rock am Ring and Rock im Park (Germany), Untold Festival (Romania), Tomorrowland (Belgium), Eurovision (whole Europe, music competition between European countries).

- Main music companies : Domino Recording Company, Bertelsmann Music Group, PolyGram, EMI (UK), Universal Music Group (Subsidiary of French company Vivendi) (whole Europe), Parlophone (UK), Ariola Records (Germany), Spinnin' Records (Netherlands), Kontor Records (Germany), Prosto (Poland), Roton (Romania), Sony Music Entertainment (whole Europe), Warner Music Group (whole Europe)

Architecture

Prehistoric Architecture

The Neolithic long house was a long, narrow timber dwelling built by the first farmers in Europe beginning at least as early as the period 5000 to 6000 BC. Knap of Howar and Skara Brae, the Orkney Islands, Scotland, are stone-built Neolithic settlement dating from 3,500 BC. Megaliths found in Europe and the Mediterranean were also erected in the Neolithic period. See Neolithic architecture.

Ancient Classical Architecture

- Ancient Greek architecture was produced by the Greek-speaking people whose culture flourished on the Greek mainland, the Peloponnese, the Aegean Islands, and in colonies in Anatolia and Italy for a period from about 900 BC until the 1st century AD. Ancient Greek architecture is distinguished by its highly formalised characteristics, both of structure and decoration. The formal vocabulary of ancient Greek architecture, in particular the division of architectural style into three defined orders: the Doric Order, the Ionic Order and the Corinthian Order, was to have profound effect on Western architecture of later periods.

- Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but differed from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and even more so under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well-engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the empire, sometimes complete and still in use.

Medieval Architecture

- Romanesque architecture combines features of ancient Roman and Byzantine buildings and other local traditions. It is known by its massive quality, thick walls, round arches, sturdy pillars, groin vaults, large towers and decorative arcading. Each building has clearly defined forms, frequently of very regular, symmetrical plan; the overall appearance is one of simplicity when compared with the Gothic buildings that were to follow. The style can be identified right across Europe, despite regional characteristics and different materials, and is most frequently seen in churches. Plenty of examples of this architecture are found alongside the Camino de Santiago.

Burgos Cathedral, built in the Gothic style.

Burgos Cathedral, built in the Gothic style. - Gothic architecture flourished in Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. Originating in 12th century France and lasting into the 16th century, Gothic architecture was known during the period as Opus Francigenum ("French work") with the term Gothic first appearing during the later part of the Renaissance. Its characteristics include the pointed arch, the ribbed vault (which evolved from the joint vaulting of Romanesque architecture) and the flying buttress. Gothic architecture is most familiar as the architecture of many of the great cathedrals, abbeys and churches of Europe.

Renaissance and Neoclassical Architecture

- Renaissance architecture began in the early 14th and lasted until the early 17th century. It demonstrates a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman architectural thought and material culture, particularly the symmetry, proportion, geometry and the regularity of parts of ancient buildings. Developed first in Florence, with Filippo Brunelleschi as one of its innovators, the Renaissance style quickly spread to other Italian cities. The style was carried to France, Germany, England, Russia and other parts of Europe at different dates and with varying degrees of impact

- Baroque architecture began in 16th-century Italy. It took the Roman vocabulary of Renaissance architecture and used it in a new rhetorical and theatrical fashion. It was, initially at least, directly linked to the Counter-Reformation, a movement within the Catholic Church to reform itself in response to the Protestant Reformation. Baroque was characterised by new explorations of form, light and shadow, and a freer treatment of classical elements. It reached its extreme form in the Rococo style.

- Palladian Architecture was derived from and inspired by the designs of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). Palladio's work was strongly based on the symmetry, perspective and values of the formal classical temple architecture of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. From the 17th century Palladio's interpretation of this classical architecture was adapted as the style known as Palladianism. It continued to develop until the end of the 18th century, and continued to be popular in Europe throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, where it was frequently employed in the design of public and municipal buildings.

19th Century Architecture

- Revivalism was a hallmark of nineteenth-century European architecture. Revivals of the Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque styles all took place, alongside revivals of the Classical styles. Regional styles, such as English Tudor were also revived, as well as non-European styles, such as Chinese (Chinoiserie) and Egyptian. These revivals often used elements of the original style in a freer way than original examples, sometimes borrowing from multiple styles at once. At Alnwick Castle, for example, Gothic revival elements were added to the exterior of the original medieval castle, while the interiors were designed in a Renaissance style.

- Art Nouveau architecture was a reaction against the eclectic styles which dominated European architecture in the second half of the 19th century. It was expressed through decoration. The buildings were covered with ornament in curving forms, based on flowers, plants or animals: butterflies, peacocks, swans, irises, cyclamens, orchids and water lilies. Façades were asymmetrical, and often decorated with polychrome ceramic tiles. The decoration usually suggested movement; there was no distinction between the structure and the ornament.

20th Century and Modern Architecture

- Art Deco architecture began in Brussels in 1903-4. Early buildings had clean lines, rectangular forms, and no decoration on the facades; they marked a clean break with the art nouveau style. After the First World War, art deco buildings of steel and reinforced concrete began to appear in large cities across Europe and the United States. Buildings became more decorated, and interiors were extremely colorful and dynamic, combining sculpture, murals, and ornate geometric design in marble, glass, ceramics and stainless steel.

- Modernist architecture is a term applied to a group of styles of architecture which emerged in the first half of the 20th century and became dominant after World War II. It was based upon new technologies of construction, particularly the use of glass, steeland reinforced concrete; and upon a rejection of the traditional neoclassical architecture and Beaux-Arts styles that were popular in the 19th century. Modernist architecture continued to be the dominant architectural style for institutional and corporate buildings into 1980s, when it was challenged by postmodernism.

- Expressionist architecture is a form of modern architecture that began during the first decades of the 20th century, in parallel with the expressionist visual and performing arts that especially developed and dominated in Germany. In the 1950s, a second movement of expressionist architecture developed, initiated by the Ronchamp Chapel Notre-Dame-du-Haut (1950–1955) by Le Corbusier. The style was individualistic, but tendencies include Distortion of form for an emotional effect, efforts at achieving the new, original, and visionary, and a conception of architecture as a work of art.

- Postmodern architecture emerged in the 1960s as a reaction against the austerity, formality, and lack of variety of modern architecture, particularly in the international style advocated by Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Embraced in the USA first, it spread to Europe. In contrast to Modernist buildings, Postmodern buildings have curved forms, decorative elements, asymmetry, bright colors, and features often borrowed from earlier periods. Colors and textures unrelated to the structure of function of the building. While rejecting the "puritanism" of modernism, it called for a return to ornament, and an accumulation of citations and collages borrowed from past styles. It borrowed freely from classical architecture, rococo, neoclassical architecture, the Viennese secession, the British arts and crafts movement, the German Jugendstil.

- Deconstructivist architecture is a movement of postmodern architecture which appeared in the 1980s, which gives the impression of the fragmentation of the constructed building. It is characterized by an absence of harmony, continuity, or symmetry. Its name comes from the idea of "Deconstruction", a form of semiotic analysis developed by the French philosopher Jacques Derrida. Besides fragmentation, Deconstructivism often manipulates the structure's surface skin and creates by non-rectilinear shapes which appear to distort and dislocate elements of architecture. The finished visual appearance is characterized by unpredictability and controlled chaos.

Literature

Europe has produced some of the most prominent or popular fiction and nonfiction writers of all time :

- Homer, Hesiod, Sappho, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Xenophon, Aristophanes, Menander, Polybius, Arrian, Plutarch, Longus (Ancient Greece)

- Plautus, Terence, Cicero, Sallust, Virgil, Livy, Ovid, Tacitus, Horace, Catullus, Pliny the Elder, Quintilian, Seneca the Younger, Pliny the Younger (Ancient Rome)

- Francis of Assisi, Guido Guinizelli, Guido Cavalcanti, Marco Polo, Francesco Petrarca, Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli, Ludovico Ariosto, Torquato Tasso, Luigi da Porto, Carlo Goldoni, Carlo Gozzi, Carlo Collodi, Giacomo Leopardi, Alessandro Manzoni, Giosuè Carducci, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Italo Svevo, Giovanni Verga, Primo Levi, Luigi Pirandello, Italo Calvino, Eugenio Montale, Salvatore Quasimodo, Andrea Camilleri, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Umberto Eco, Dario Fo (Italy)

- Chrétien de Troyes, Rabelais, Montaigne, Dumas, Pierre Corneille, Racine, Molière, Jean de La Fontaine, Marivaux, Voltaire, Beaumarchais, Verne, Balzac, Musset, Flaubert, Stendhal, Proust, Camus, Hugo, Baudelaire, Verlaine, Maupassant, Aragon, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Gautier, Anatole France, Saint-Exupéry, Apollinaire, de Beauvoir, Sartre, Rolland, Diderot, Foucault, Mauriac, Gide, Saint-John Perse, Simon, Gao Xingjian, Le Clézio, Modiano (France)

- Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Goncharov, Mikhail Bakunin, Mikhail Lermontov, Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Peter Kropotkin, Anton Chekhov, Maxim Gorky, Ivan Bunin, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Boris Pasternak, Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Bulgakov, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Sergei Yesenin, Vladimir Nabokov, Mikhail Sholokhov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Joseph Brodsky (Russia)

- Jorge Manrique, Garcilaso de la Vega, Miguel de Cervantes, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Lope de Vega, Francisco de Quevedo, Luis de Góngora, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, Leopoldo Alas, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Pío Baroja, José Echegaray, Miguel de Unamuno, Federico García Lorca, Vicente Aleixandre, Camilo José Cela, Mario Vargas Llosa (Spain)

- Luís de Camões, José Maria de Eça de Queiroz, Fernando Pessoa, José Saramago (Portugal)

- Salvador Espriu, Mercè Rodoreda, Joan Salvat-Papasseit, Josep Carner (Catalan language)

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Johann Gottfried Herder, Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Heinrich von Kleist, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, Heinrich Heine, Gerhart Hauptmann, Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Rudolf Christoph Eucken, Anne Frank, Hermann Hesse, Nelly Sachs, Günter Grass, Patrick Süskind (Germany)

- Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Zygmunt Krasiński, Joseph Conrad, Czesław Miłosz, Zbigniew Herbert, Witold Gombrowicz, Jan Kochanowski, Mikołaj Rej, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Wisława Szymborska, Stanisław Lem, Andrzej Sapkowski (Poland)

- William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, Bernart de Ventadorn, Arnaut Daniel, Comtessa de Dia, Frédéric Mistral (Occitan language)

- Lajos Kossuth, Imre Kertész (Hungary)

- Franz Kafka, Jaroslav Seifert, Milan Kundera (Czech Republic)

- William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Geoffrey Chaucer, Jane Austen, H. G. Wells, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, J. R. R. Tolkien, J. K. Rowling, Beatrix Potter, J. M. Barrie, Walter Scott, D. H. Lawrence, George Orwell, Virginia Woolf, C. S. Lewis, John Milton, Terry Pratchett, Mary Shelley, Roald Dahl, Lewis Carroll, Agatha Christie, Daniel Defoe, Alan Moore, Rudyard Kipling, Aldous Huxley, Harold Pinter (United Kingdom)

- Laurence Sterne, Maria Edgeworth, Bram Stoker, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett, John Millington Synge, W.B. Yeats, Frank O'Connor, Seán Ó Ríordáin, Sean O'Casey, Máire Mhac an tSaoi, Brian Friel, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Seamus Heaney (Ireland)

- Heinrich von Veldeke, Jacob Cats, Joost van den Vondel, Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft, Multatuli, Harry Mulisch, Willem Frederik Hermans, Cees Nooteboom (The Netherlands)

- Karl Adolph Gjellerup, Hans Christian Andersen, Johannes Vilhelm Jensen (Denmark)

- Georges Simenon, Emile Verhaeren, Maurice Maeterlinck, Willem Elsschot, Louis Paul Boon, Hugo Claus (Belgium)

- Sigrid Undset, Henrik Ibsen, Knut Hamsun, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (Norway)

- Ivan Vazov (Bulgaria)

- Ivo Andric (Serbia)

- Frans Eemil Sillanpää (Finland)

- Elfriede Jelinek (Austria)

- Halldór Laxness (Iceland)

- Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko (Ukraine)

- Eugène Ionesco, Mircea Eliade, Mihai Eminescu, Paul Celan, Emil Cioran, Herta Muller, Elie Wiesel (Romania)

- Verner von Heidenstam, Stieg Larsson, Pär Lagerkvist, August Strindberg, Emanuel Swedenborg, Eyvind Johnson (Sweden)

Film

Antoine Lumière realized, on 28 December 1895, the first projection, with the Cinematograph, in Paris.[13] In 1897, Georges Méliès established the first cinema studio on a rooftop property in Montreuil, near Paris. Some notable European film movements include German Expressionism, Italian neorealism, French New Wave, Polish Film School, New German Cinema, Portuguese Cinema Novo, Czechoslovak New Wave, Dogme 95, New French Extremity, and Romanian New Wave.

Cinecittà film studios

Cinecittà film studios

The cinema of Europe has its own awards, the European Film Awards. Main festivals : Cannes Film Festival (France), Berlin International Film Festival (Germany). The Venice Film Festival (Italy) or Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Cinematografica di Venezia, is the oldest film festival in the world. Philippe Binant realized, on 2 February 2000, the first digital cinema projection in Europe.[15]

European films

- Le fabuleux destin d'Amelie Poulain (fr).

- Train spotting (uk)

- La Strada (it)

- Glass (nl)

- The Lives of Others (de)

- Goodbye Lenin (de)

Video games

Science

- CERN (/sɜːrn/; French: [sɛʀn]) : The European Organization for Nuclear Research, is the birthplace of the World Wide Web and home of the world's largest machine : the Large Hadron Collider. It is the world's largest particle physics laboratory, situated in the northwest suburbs of Geneva on the Franco–Swiss border, established in 1954. In November 2010, the collisions obtained were able to generate the highest temperatures and densities ever produced in an experiment, creating a "mini-Big Bang" a million times hotter than the centre of the Sun.[16]

- ESA : The European Space Agency's space flight program includes human spaceflight,[17] mainly through the participation in the International Space Station program, the launch and operations of unmanned exploration missions to other planets and the Moon, Earth observations, science, telecommunication as well as maintaining a major spaceport, the Guiana Space Centre at Kourou, French Guiana and designing launch vehicles. The main European launch vehicle Ariane 5 is operated through Arianespace with ESA sharing in the costs of launching and further developing this launch vehicle. On 12 November 2014, ESA's Philae probe achieved the first-ever soft landing on a comet.

Europe has produced some of the most influential scientists and inventors in history.

- Germany: Karl Benz, Carl Bosch, Karl Ferdinand Braun, Wernher von Braun, Robert Bunsen, Gottlieb Daimler, Rudolf Diesel, Albert Einstein, Daniel Fahrenheit, Gottlob Frege, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Johannes Gutenberg, Ernst Haeckel, Otto Hahn, Werner Heisenberg, Heinrich Rudolf Hertz, Alexander von Humboldt, Johannes Kepler, Robert Koch, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Georg Ohm, Max Planck, Bernhard Riemann, Wilhelm Röntgen, Theodor Schwann, Max Weber, Alfred Wegener, Wilhelm Wundt, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, Konrad Zuse

- France: Pierre Abelard, Louis Pasteur, Antoine Lavoisier, Frantz Fanon, Mouloud Mammeri, Henri Becquerel, Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot, Pierre de Fermat, the Montgolfier brothers, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Léon Foucault, Auguste and Louis Lumière, Pierre Curie, Jacques Lacan, Luc Montagnier, Albert Jacquard

- The Netherlands: Willebrord Snel van Royen, Christiaan Huygens, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Jan Swammerdam, C. H. D. Buys Ballot, Hugo de Vries, Hendrik Lorentz, Jan Oort, Jacobus van 't Hoff, Johannes Diderik van der Waals, Pieter Zeeman, Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, Gerard Kuiper, Frits Zernike, Nikolaas Tinbergen, Jan Tinbergen, Martinus Veltman, Gerard 't Hooft

- United Kingdom: Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Michael Faraday, Alan Turing, James Joule, Edward Jenner, Robert Hooke, Charles K. Kao, George Stephenson, Florence Nightingale, George Cayley, Frank Whittle, Stephen Hawking, John Dalton, Tim Berners-Lee, James Watt, Alexander Fleming, Alexander Graham Bell, John Logie Baird, James Clerk Maxwell, Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes

- Russia: Sergey Korolyov, Sofia Kovalevskaya, Lev Landau, Nikolai Lobachevsky, Mikhail Lomonosov, Ilya Mechnikov, Dmitri Mendeleev, Ivan Pavlov, Grigori Perelman, Alexander Popov, Andrei Sakharov, Vladimir Shukhov, Igor Sikorsky, Nikolai Vavilov, Vladimir Zworykin

- Italy: Gerolamo Cardano, Fibonacci, Giovanni Domenico Cassini, Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, Giordano Bruno, Evangelista Torricelli, Amedeo Avogadro, Alessandro Volta, Guglielmo Marconi, Ettore Majorana, Enrico Fermi, Margherita Hack

- Poland: Sendivogius, Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Hevelius, Ignacy Łukasiewicz, Marie Curie, Rudolf Weigl

- Greece: Archimedes, Euclid, Ptolemy

- Hungary: Ottó Bláthy, Ányos Jedlik, John von Neumann, Leó Szilárd, Edward Teller

- Austria: Ludwig Boltzmann, Sigmund Freud, Kurt Gödel, Erwin Schrödinger

- Ireland: Lord Kelvin, Robert Boyle, William Rowan Hamilton

- Spain: Miguel Servet, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Isaac Peral, Leonardo Torres Quevedo, Severo Ochoa.

- Sweden: Carl Linnaeus, Alfred Nobel, Anders Celsius

- Finland: Artturi Ilmari Virtanen, Ragnar Granit, Johan Gadolin, Linus Torvalds, Elias Lönnrot

- Denmark: Tycho Brahe, Niels Bohr

- Serbia: Nikola Tesla, Mihajlo Pupin, Milutin Milanković, Miomir Vukobratović

- Switzerland; Jacob, Johann and Daniel Bernoulli, Leonhard Euler, Carl Jung, Paracelsus

- Bulgaria: John Vincent Atanasoff, Peter Petroff

- Croatia: Andrija Mohorovičić, Roger Joseph Boscovich

- Romania: Henri Coandă, Nicolae Paulescu

Philosophy

European philosophy is a predominant strand of philosophy globally, and is central to philosophical enquiry in America and most other parts of the world which have fallen under its influence.

The Greek schools of philosophy in antiquity provide the basis of philosophical discourse that extends to today. Christian thought had a huge influence on many fields of European philosophy (as European philosophy has been on Christian thought too), sometimes as a reaction. Many political ideologies were theorised in Europe such as capitalism, communism, fascism, socialism or anarchism.

Perhaps one of the most important single philosophical periods since the classical era were the Renaissance, the Age of Reason and the Age of Enlightenment. There are many disputes as to its value and even its timescale. What is indisputable is that the tenets of reason and rational discourse owe much to René Descartes, John Locke and others working at the time.

Other important European philosophical strands include: Analytic philosophy, Anarchism, Christian Democracy, Communism, Conservatism, Constructionism, Deconstructionism, Empiricism, Epicureanism, Existentialism, Fascism, Humanism, Idealism, Internationalism, Liberalism, Logical positivism, Marxism, Materialism, Monarchism, Nationalism, Perspectivism, Platonism, Positivism, Postmodernism, Protestantism, Rationalism, Relativism, Republicanism, Romanticism, Scepticism, Scholasticism, Social Democracy, Socialism, Stoicism, Structuralism, Thomism, Utilitarianism, Spenglerism.

- Ockham, More, Bacon, Hobbes, Locke, Smith, Bentham, Stuart Mill, Russel (England)

- Leibniz, Kant, Schopenhauer, Feuerbach, Benjamin, Engels, Hegel, Eucken, Jaspers, Spengler, Marcuse, Marx, Nietzsche, Dilthey, Fichte, Heidegger, Husserl, Habermas, Stirner, Meister Eckhart, Weishaupt (Germany)

- Montaigne, Descartes, Malebranche, Pascal, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau, Comte, Bergson, Bachelard, Lévinas, Merleau-Ponty, Ricœur, Lévi-Strauss, Camus, de Beauvoir, Sartre, Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze (France)

- Thomas à Kempis, Erasmus, Spinoza, Hugo Grotius (The Netherlands)

- Popper, Wittgenstein (Austria)

- Aquinas, Pico della Mirandola, Machiavelli, Vico, Beccaria (Italy)

- Kierkegaard (Denmark)

- Francisco de Vitoria, Francisco Suárez (Spain)

Religion

Indo-European religions were: Baltic mythology, Celtic polytheism, Germanic paganism, Ancient Greek religion, Etruscan religion, and Slavic mythology.

The Eurobarometer Poll 2005[18] found that, on average, 52% of the citizens of EU member states state that they "believe in God", 27% believe there is some sort of spirit or life force while 18% do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force. 3% declined to answer. According to new polls about Religiosity in the European Union in 2012 by Eurobarometer, Christianity is the largest religion in the European Union accounting 72% of EU citizens.[19] Non believer/Agnostic account 16%,[19] Atheist account's 7%,[19] and Muslim 2%.[19]

Christianity has been the dominant religion shaping European culture for at least the last 1700 years.[20][21][22][23][24] Modern philosophical thought has very much been influenced by Christian philosophers such as St Thomas Aquinas and Erasmus. And throughout most of its history, Europe has been nearly equivalent to Christian culture,[25] The Christian culture was the predominant force in western civilization, guiding the course of philosophy, art, and science.[26][27] The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom" many even attribute Christianity for being the link that created a unified European identity.[28]

The most popular religions of Europe are the following (by dominant religion):

- Christianity is the largest religion in Europe, with 76.2% of Europeans considering themselves Christian,[29]

- Catholicism: Countries with significant Catholic populations are Portugal,[30] Spain,[31] Poland,[19] > France,[32] Luxembourg,[33] Belgium,[19] Ireland,[34] Northern Ireland (UK),[35] Italy,[36] Malta,[37] Austria,[38] Hungary,[39] Slovenia,[40] Croatia,[41] Slovakia[42] and Lithuania.[43]

- There are significant Catholic minorities in the Netherlands,[44] southern Germany,[45] Switzerland, the Czech Republic,[46] western and central Belarus, western Ukraine,[47] Hungarian-speaking Romania, Albania, parts of Russia, the Latgale region of Latvia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, England (UK), Scotland (UK),[48] and Wales (UK),[49] and indeed small minorities in most of the other European countries.

- Eastern Orthodoxy: The countries with significant Orthodox populations are Albania,[50] Belarus,[51][52] Bosnia and Herzegovina,[53] Bulgaria,[54] Cyprus,[55] Georgia,[56] Greece,[57][58] Macedonia,[59] Moldova,[60] Montenegro,[61] Romania,[62] Russia,[63] Serbia[64] and Ukraine.[65]

- Protestantism: Countries with significant Protestant populations are Norway,[66] Iceland,[67] Sweden,[68] Finland,[69] Estonia,[70] Latvia,.[71] the United Kingdom,[72] Denmark,[73] Germany[74] and Switzerland.[75] There are significant minorities in France, Czech Republic, Slovakia, the Netherlands,[76] Austria, Hungary,[39] and indeed small minorities in most European countries.

- Islam: The countries with a majority Muslim population are Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The region of East Thrace (Turkey) and Serbian province of Kosovo and Metohija also have a majority Muslim population. As of 2010, about 5.2% of European citizens identified themselves as Muslims,[77] with many of them living in EU member states like France, Germany, the UK, Belgium, Austria, Bulgaria, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Outside of the EU also have significant Muslim minorities like Macedonia, Montenegro, Crimea, Serbia, parts of European Russia and Georgia.[78]

- Judaism

Popular culture

Cuisine

The cuisines of European countries are diverse by themselves, although there are common characteristics that distinguishes European cooking from cuisines of Asian countries and others. Compared with traditional cooking of Asian countries, for example, meat is more prominent and substantial in serving-size. Steak in particular is a common dish across Europe. European cuisines also put substantial emphasis on sauces as condiments, seasonings, or accompaniments (in part due to the difficulty of seasonings penetrating the often larger pieces of meat used in European cooking). Many dairy products are utilized in the cooking process, except in nouvelle cuisine. Wheat-flour bread has long been the most common sources of starch in this cuisine, along with pasta, dumplings and pastries, although the potato has become a major starch plant in the diet of Europeans and their diaspora since the European colonization of the Americas. The common way to eat a beef or pork chop is with a knife in the right hand and a fork in the left way. To begin a such meal by first chopping the meat up, and then just use a fork with the right hand, is generally considered to be bad manners, especially at restaurants.

Austrian Wiener Schnitzel

Austrian Wiener Schnitzel

- Italian pasta

Spanish paella

Spanish paella- Northern Europe Rollmops

- Greek moussaka

Clothing

The earliest definite examples of needles originate from the Solutrean culture, which existed in France and Spain from 19,000 BC to 15,000 BC. The earliest dyed flax fibers have been found in a cave the Republic of Georgia and date back to 36,000 BP. See Clothing in ancient Rome, 1100–1200 in fashion, 1200–1300 in fashion, 1300–1400 in fashion, 1400–1500 in fashion, 1500–1550 in fashion, 1550–1600 in fashion, 1600–1650 in fashion, 1650–1700 in fashion, Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution.

Main European clothing brands are:

Video games

Some of the most popular games of all time come from Europe: Grand Theft Auto, Tomb Raider, The Witcher, Cossacks: European Wars, Colin McRae: Dirt, Far Cry, Asphalt, The Settlers, The Patrician, Need For Speed, Angry Birds, Cut the Rope, Brain Challenge, Rayman, Beyond Good & Evil, Heavy Rain, Beyond: Two Souls, Watch Dogs, World Rally Championship, Batman: Arkham City, Banjo-Kazooie, LittleBigPlanet, Block Breaker Deluxe, Crysis, Tetris, Assassin's Creed, Vera Blanc, Europa Universalis, Kinect Sports, Hysteria Project and The Getaway.

Sport

Europe's influence on sport is enormous. European sports include:

- Association football, which has contested origins between United Kingdom and Italy (where Benito Mussolini insisted the game be called by the name Calcio). What is uncontestable is that the oldest association is The Football Association of England (1863) and the first international match was between Scotland and England (1872). It is now the world's most popular sport and is played throughout Europe.

- Cricket has its origins in south eastern Britain. It's popular throughout England and Wales, and parts of Netherlands. It is also popular in other areas in Northwest Europe. It is however very popular worldwide, especially in Africa, Australia, New Zealand and the Indian subcontinent.

- Cycling, which is immensely popular as a means of transport, has most of its sporting adherents in Europe. Tour de France is the world's most watched live annual sporting event. The bicycle itself is probably from France (see History of the bicycle).

- The discus throw, javelin throw and shot put have their origins in ancient Greece. The Olympics, both ancient and modern, have their origins too in Europe, and have a massive influence globally.

- Field Hockey as a modern game, began in 18th Century Britain with Ireland having the oldest federation. It is popular in the Western Europe, the Indian subcontinent, Australia and East Asia. Ice hockey, popular in Europe and North America may derive from this sport.

- Golf, one of the most popular sports in Europe, Asia and North America, has its origins in Scotland, with the oldest course being at Musselburgh.

- Handball, which is popular in Europe and elsewhere, has its origins in antiquity. The modern game is from Denmark and Germany with Germany having been involved in both the first women's and men's internationals.

- Rugby League and Rugby Union which both have similar origins to football. Rugby Union is the older of the two codes and has rules that date from 1845 (see articles: History of rugby league and History of rugby union). They acrimoniously split in the late 19th century over the treatment of injured players. Rugby league gradually changed its laws over the next century with the end result that today both sports have little in common, apart from the basics. They have both been carried abroad by colonization, particularly to many former British colonies. American Football and Canadian Football are derivatives of rugby.

- Tennis which originates from United Kingdom and related games such as Table Tennis derive from the game Real Tennis which is from France. It is popular throughout the world.

In addition, Europe has numerous national or regional sports which do not command a large international following outside of emigrant groups. These include:

- Alpine Wrestling in Switzerland.

- Bandy in Russia, Sweden and Finland

- Basque Pelota in parts of Spain and France, and which has been brought to the Americas by emigrants.

- Bullfighting in Spain, Portugal, and parts of southern France near the Spanish Border.

- Gaelic Football in Ireland, which influenced Australian rules football.

- Gaelic Handball (Ireland) which was taken to the United States in the form of American Handball.

- Hurling in Ireland.

- Korfbal in the Netherlands and Belgium.

- Pesäpallo (Boboll) in Finland

- Pétanque, Boules, Irish Road Bowling, Skittles, Bocce, and Bowls and others are variations of bowling games which are popular throughout Europe and have been spread around the world.

- Rounders from Britain[79][80] now popular in northwest Europe from which Baseball derives.

- Shinty in Scotland, United Kingdom, which influenced ice hockey in Canada (see also Shinny).

- Trotting in southern Europe.

Some sport competitions feature a European team gathering athletes from different European countries. These teams use the European flag as an emblem. The most famous of these competitions is the Ryder Cup in golf. Some sporting organisations hold European Championships like European Cricket Council, the European Games, the European Rugby Cup (Club/Regional competition), the European SC Championships, the FIRA - Association of European Rugby, the IIHF, the Mitropa Cup, the Rugby League European Federation - European Nations Cup, the Sport in the European Union and the UEFA.

Capitals of Culture

Each year since 1985 one or more cities across Europe are chosen as European Capital of Culture. Here are the past and future capitals:

- 1985: Athens

- 1986: Florence

- 1987: Amsterdam

- 1988: Berlin

- 1989: Paris

- 1990: Glasgow

- 1991: Dublin

- 1992: Madrid

- 1993: Antwerp

- 1994: Lisbon

- 1995: Luxembourg

- 1996: Copenhagen

- 1997: Thessaloniki

- 1998: Stockholm

- 1999: Weimar

- 2000: Avignon, Bergen, Bologna, Brussels, Helsinki, Kraków, Prague, Reykjavík, Santiago de Compostela

- 2001: Rotterdam, Porto

- 2002: Bruges, Salamanca

- 2003: Graz

- 2004: Genoa, Lille

- 2005: Cork

- 2006: Patras

- 2007: Sibiu, Luxembourg, Greater Region

- 2008: Liverpool, Stavanger

- 2009: Vilnius Linz

- 2010: Essen (representing the Ruhr), Istanbul, Pécs

- 2011: Turku, Tallinn

- 2012: Guimarães, Maribor

- 2013: Marseille, Košice

- 2014: Umeå, Riga

- 2015: Mons, Plzeň

- 2016: San Sebastián, Wrocław

- 2017: Aarhus, Paphos

- 2018: Malta, Netherlands

- 2019: Plovdiv, Bulgaria and Matera, Italy

- 2020: Galway, Ireland and Rijeka, Croatia

Housing

Symbols

See also

References

- ↑ Mason, D. (2015). A Concise History of Modern Europe: Liberty, Equality, Solidarity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 2.

- ↑ Cf. Berting (2006:51).

- ↑ Cederman (2001:2) remarks: "Given the absence of an explicit legal definition and the plethora of competing identities, it is indeed hard to avoid the conclusion that Europe is an essentially contested concept." Cf. also Davies (1996:15); Berting (2006:51).

- ↑ Cf. Jordan-Bychkov (2008:13), Davies (1996:15), Berting (2006:51-56).

- 1 2 K. Bochmann (1990) L'idée d'Europe jusqu'au XXè siècle, quoted in Berting (2006:52). Cf. Davies (1996:15): "No two lists of the main constituents of European civilization would ever coincide. But many items have always featured prominently: from the roots of the Christian world in Greece, Rome and Judaism to modern phenomena such as the Enlightenment, modernization, romanticism, nationalism, liberalism, imperialism, totalitarianism."

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berting 2006, p. 52

- ↑ Berting 2006, p. 51

- ↑ Duran (1995:81)

- ↑ "EliotPassages". www3.dbu.edu.

- ↑ 1960–1969, EMI Group Ltd, archived from the original on 28 May 2008, retrieved 31 May 2008

- ↑ Paul At Fifty: Paul McCartney Time Magazine'.' Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ 100 Greatest Artists Of All Time: The Beatles (No.1) Rolling Stone'.' Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Universalis, Encyclopædia. "PRÉSENTATION DU CINÉMATOGRAPHE LUMIÈRE". Encyclopædia Universalis.

- ↑ Avedon, Richard (14 April 2007). "The top 21 British directors of all time". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

Unquestionably the greatest filmmaker to emerge from these islands, Hitchcock did more than any director to shape modern cinema, which would be utterly different without him. His flair was for narrative, cruelly withholding crucial information (from his characters and from the audience) and engaging the emotions of the audience like no one else.

- ↑ Cahiers du cinéma, n°hors-série, Paris, April 2000, p. 32 (cf. also Histoire des communications, 2011, p. 10.).

- ↑ "Large Hadron Collider (LHC) generates a 'mini-Big Bang'". BBC News. 8 November 2010.

- ↑ . 23 February 2017 https://lannuaire.service-public.fr/institutions-europeennes/institution-europeenne_185293. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-24. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Discrimination in the EU in 2012" (PDF), Special Eurobarometer, 393, European Union: European Commission, p. 233, 2012, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012, retrieved 14 August 2013 The question asked was "Do you consider yourself to be...?" With a card showing: Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Other Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, and Non-believer/Agnostic. Space was given for Other (SPONTANEOUS) and DK. Jewish, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu did not reach the 1% threshold.

- ↑ Religions in Global Society - Page 146, Peter Beyer - 2006

- ↑ Cambridge University Historical Series, An Essay on Western Civilization in Its Economic Aspects, p.40: Hebraism, like Hellenism, has been an all-important factor in the development of Western Civilization; Judaism, as the precursor of Christianity, has indirectly had had much to do with shaping the ideals and morality of western nations since the Christian era.

- ↑ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p.2: That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization — the civilization of western Europe and of America— have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo - Graeco - Christianity, Catholic and Protestant.

- ↑ Horst Hutter, University of New York, Shaping the Future: Nietzsche's New Regime of the Soul And Its Ascetic Practices (2004), p.111:three mighty founders of Western culture, namely Socrates, Jesus, and Plato.

- ↑ Fred Reinhard Dallmayr, Dialogue Among Civilizations: Some Exemplary Voices (2004), p.22: Western civilization is also sometimes described as "Christian" or "Judaeo- Christian" civilization.

- ↑ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ↑ Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. Early Middle Ages: St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ↑ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ↑ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 108. ISBN 9780813216836.

- ↑ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population". 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Census - Final results : Portugal - 2011". Statistics Portugal. 20 November 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-21.

- ↑ Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (April 2014). "Barómetro Abril 2014" (PDF). p. 153. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ "Observatoire du patrimoine religieux". 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013.

94% des édifices sont catholiques (dont 50% églises paroissiales, 25% chapelles, 25% édifices appartenant au clergé régulier)

- ↑ "Les religions au Luxembourg".

- ↑ "Table 36: Persons, male and female, classified by religious denomination with actual percentage change, 2006 and 2011" (PDF). This is Ireland, Highlights from Census 2011, Part 1. Central Statistics Office. p. 104. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ "Census 2011: Religion: KS211NI (administrative geographies)". nisra.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Ipsos MORI, Views on globalisation and faith, 5 July 2011

- ↑ http://www.clerus.org/clerus/dati/2008-12/05-6/proportioncathos08.htm

- ↑ Kirchenaustritte gingen 2012 um elf Prozent zurück Archived October 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "2011 Hungary Census Report" (PDF).

- ↑ "6. Population by religion, municipalities, Slovenia, Census 2002". www.stat.si.

- ↑ "STANOVNIŠTVO PREMA VJERI, POPISI 2001. I 2011" [POPULATION BY RELIGION, 2001 AND 2011 CENSUSES] (in Croatian). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 17 December 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ↑ "Table 14 Population by religion" (PDF). Statistical Office of the SR. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-14. Retrieved Jun 8, 2012.

- ↑ Department of Statistics to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. "Ethnicity, mother tongue and religion". Archived from the original on 2014-10-08. . 2013-03-15.

- ↑ "Kerkelijke gezindte en kerkbezoek; vanaf 1849; 18 jaar of ouder". 15 October 2010.

- ↑ "Kirchenmitgliederzahlen am 31. Dezember 2010" (PDF). ekd.de. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Population by religious belief and by municipality size groups" (PDF). Czech Statistical Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ Piotr Eberhardt. Ethnic groups and population changes in twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: history, data, analysis. M.E. Sharpe, 2003. pp.92–93. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5

- ↑ "Scotland's Census 2011 – Table KS209SCb" (PDF). scotlandscensus.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "2011 Census: Key Statistics for Wales, March 2011". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ "Albania". International Religious Freedom Report 2009. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, United States Department of State. 26 October 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ↑ "Religion and denominations in the Republic of Belarus by the Commissioner on Religions and Nationalities of the Republic of Belarus from November 2011" (PDF).

- ↑ http://features.pewforum.org/grl/population-percentage.php%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ "International Religious Freedom Report 2008 – Bosnia and Herzegovina".

- ↑ 2011 census, p. 5.

- ↑ .

- ↑ 2002 Census Results. p. 132

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- ↑ The newest polls show about 20% Greek citizens being irreligious which is much more than 1%. Ultimately, the statistics are disputed until the results of the new census.

- ↑ "Religions". CIA World Factbook. 2002. Retrieved 2013-06-21.

- ↑ "Moldovans Rally To Protest Formal Recognition Of Islam". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ↑ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). Monstat. pp. 14, 15. Retrieved July 12, 2011. For the purpose of the chart, the categories 'Islam' and 'Muslims' were merged; 'Buddhist' (.02) and Other Religions were merged; 'Atheist' (1.24) and 'Agnostic' (.07) were merged; and 'Adventist' (.14), 'Christians' (.24), 'Jehovah Witness' (.02), and 'Protestants' (.02) were merged under 'Other Christian'.

- ↑ "Eastern Orthodoxy | Christianity". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ↑ http://www.pewforum.org/2011/12/19/global-christianity-exec/ Pew

- ↑ Book 3 Page 13 Archived April 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "What religious group do you belong to?". Sociology poll by Razumkov Centre about the religious situation in Ukraine (2006) Archived 2014-04-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Religious communities and life stance communities, 1 January 2013". Statistics Norway. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ "Populations by religious organizations 1998-2014". Reykjavík, Iceland: Statistics Iceland.

- ↑ Svenska kyrkan i siffror Svenska kyrkan

- ↑ Religious affiliation of the population, share of population, % 1950–2013 Statistics Finland

- ↑ "PC0454: AT LEAST 15-YEAR-OLD PERSONS BY RELIGION, SEX, AGE GROUP, ETHNIC NATIONALITY AND COUNTY, 31 DECEMBER 2011". Statistics Estonia. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ↑ "Tieslietu ministrijā iesniegtie reliģisko organizāciju pārskati par darbību 2011. gadā" (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 2012-11-26. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ↑ "2011 Census: KS209EW Religion, local authorities in England and Wales". ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Church membership 1990–2014 Archived February 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Kirkeministeriet (in Danish)

- ↑ . Zensus 2011 - Page 10.

- ↑ "Ständige Wohnbevölkerung ab 15 Jahren nach Religions- / Konfessionszugehörigkeit, 2012". bfs.admin.ch (Statistics) (in German, French, and Italian). Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2014. Archived from the original (XLS) on 2012-01-06. Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- ↑ Donk, W.B.H.J. van de; Jonkers, A.P.; Kronjee, G.J.; Plum, R.J.J.M. (2006). Geloven in het publieke domein, verkenningen van een dubbele transformatie, WRR, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam

- ↑ http://www.pewforum.org/uploadedfiles/Topics/Demographics/Muslimpopulation.pdf Islam in Europe states 3.2% Muslims in European Union, but non-European Union countries harbour even more Muslims so percents go to about 5.2%.

- ↑ "Table: Muslim Population by Country". PEW Research Centre.

- ↑ Alice Bertha Gomme, Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Volume 2, 1898

- ↑ NRA-rounders.co.uk Archived November 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. History of Rounders

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culture of Europe. |

- Eurolinguistix.com

- Europe.org.uk - online European culture magazine (EU London Office)

- TheEuropeanLibrary.org, The European Library, gateway to Europe's national libraries

- Europeana.eu European Digital Library

- Europa.eu, EU Culture Portal (archived)

- Cultural areas of Europe

.jpg)