White people in Kenya

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 41,500 (0.1% of population) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nairobi Province, Rift Valley Province, Coast Province | |

| Languages | |

| English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity, Atheism |

White Kenyans are those born in or resident in Kenya who descend from Europeans and/or identify themselves as White. There is currently a minor but relatively prominent white community in Kenya, mainly descended from British, but also to a lesser extent Italian and Greek, migrants dating from the colonial period.

History

The Age of Discovery first led to European interaction with the region of present-day Kenya. The coastal regions were seen as a valuable foothold in eastern trade routes, and Mombasa became a key port for ivory. The Portuguese established a presence in the region for two hundred years between 1498–1698, before losing control of the coast to the Sultans of Oman.

European exploration of the interior commenced in 1844 when two German missionaries, Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann, ventured inland with the aim of spreading Christianity. The region soon sparked the imagination of other adventurers, and gradually their stories began to awaken their governments to the potential of the area.

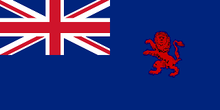

The rise of New Imperialism in the late 19th century, intensified European interest in the region. The initial driving force lay with pioneering businessmen, such as Carl Peters and William Mackinnon seeking to establish lucrative trade routes in the region. These businessmen would compel their respective governments to protect their trading interests, and in 1885 eastern Africa was carved-up between Britain, Germany and France. The British assumed control of the regions of Kenya and Uganda, and governed it through the Imperial British East Africa Company. In 1895, administration was transferred to the Foreign Office, and the East Africa Protectorate was established.

East Africa Protectorate

Having acquired Kenya and Uganda, the British sought to develop infrastructure and link the coast to Lake Victoria. The Uganda Railway serves as a lasting legacy of this ambition. The railway opened up much of the Kenyan interior to European settlement, and in 1899 British pioneers established Nairobi as a settler outpost. The period saw an influx of European settlers and farmers seeking to make a fortune, most notably the British peer Lord Delamere. Many of these settlers imagined an "empty" Africa where they hoped to recreate a society that mirrored their fantasy of manorial Europe, where they would rule as lords and Africans would serve as retainers.

In 1903 there were just fewer than 400 European settlers in British East Africa; by 1912 about 1000. The British government offered 99- and 999-year leases to encourage settlement, as well as land tax exemption into the 1930s. The state also subsidized white farmers' produce so that black smallholders could not compete in open markets. Although large stretches of Kenya at the time were sparsely populated, European colonists ended up settling in one of the most heavily occupied regions, alienating local farmers with the aid of the colonial state. From the beginning, European settlement dispossessed Africans, both through legal and extra-legal means, with a discourse arguing that WaKamba, Gikuyu, and Embu had no title to the land, as they had not improved it or were "nomadic tribes." Many were crowded onto "Native Reserves"; some populations came back to their original homes to be classified as "squatters" and often then served as labor on colonists' plantations. Europeans typically acquired plantation estates covering five hundred acres, most of which then fell fallow. The inexpensiveness of the land (as little as 1d./acre) led to many land purchases by speculators.

Kenya Colony

Life for Europeans in Kenya during this time would later be immortalised in Karen Blixen's memoir Out of Africa. The presence of herds of elephants and zebra, and other wild animals on these estates drew wealthy aristocracy from Europe and America, who came attracted by big game hunting. Nairobi was sharply segregated. More than 30,000 South Asian settlers came to Kenya from British India, but they were legally barred from purchasing real estate in the White Highlands.

Land alienation, forced labor, and African participation in higher education, bureaucratic institutions, and the First World War helped spark a substantive Kenyan nationalist movement in the 1920s. Leaders such as Jomo Kenyatta and Henry Thuku highlighted a view of an unjust political and social situation for the vast majority of Kenyans. Following World War II, some Kenyans began a violent anti-colonial campaign centered largely on the Kikuyu known as the Mau Mau Uprising. The deaths of dozens of European settlers and their African servants, triggered a war with the British government that resulted in twenty thousand Kenyan dead. British counter-insurgency tactics included forcibly relocating civilians into "villagisation" schemes, and detaining and torturing Mau Mau suspects in prison camps.

Independence

By the early 1960s, Britain's political willingness to maintain Kenya as a colony was in decline and in 1962 the Lancaster House agreement set a date for Kenya's independence. Realising that a unilateral declaration of independence course like Rhodesia's was not possible after the Mau-Mau uprising, the majority of the 60,000 white settlers considered emigration.[1] Along with Kenyan Asians, Europeans and their descendants were given the choice of retaining their British passports and suffering a diminution in rights, or acquiring new Kenyan passports. Few chose to acquire citizenship, and many white Kenyans departed the country. The World Bank led a willing-buyer-willing-seller scheme, known as the 'million acre' scheme that was largely financed by secret British subsidies. The scheme saw the redistribution of swathes of white-owned farmland to the newly prosperous Kikuyu elite.

There were an estimated 41,500 white people in Kenya as of 2009, of which 7,600 were Kenya citizens [2] . The proportion that are Kenya citizens has likely increased due to the implementation of dual nationality in 2010. There are also British citizens residing in Kenya who may be of any race; according to the BBC, they numbered at about 32,000 in 2006.[3]

Socioeconomics

Economically, virtually all Europeans in Kenya belong to the middle- and upper-middle-class. They formerly clustered in the country's highland region, the so-called 'White Highlands', where the Cholmondeley (Delamere) family, as one of the few remaining white landowners, still owns over 100,000 acres (400 km²) of farmland (mainly the vast Soysambu Estate) in the Rift Valley. Nowadays, only a small minority of them still are landowners (livestock and game ranchers, horticulturists and farmers), whereas the majority work in the tertiary sector: in finance, import, air transport, and hospitality.

Societal integration

Apart from isolated individuals such as anthropologist and conservationist Richard Leakey, F.R.S., who has retired, Kenyan white people have virtually completely retreated from Kenyan politics, and are no longer represented in public service and parastatals, from which the last remaining staff from colonial times retired in the 1970s.

The recent homicide case of the white Kenyan dairy and livestock farmer and game rancher, Hon. Thomas Cholmondeley, a descendant of British aristocrats, has brought into question the class bias of the judicial system of the Commonwealth country and the resentment of many Kenyans toward what is perceived as white privilege. The book and movie White Mischief told the tale slightly involving an earlier member of the Cholmondeley family, The 4th Baron Delamere (popularly known as Tom Delamere), who was married to Diana Broughton, whose lover was murdered in Nairobi in the 1940s. Her first husband was tried and acquitted. See also the Happy Valley set.[4]

Controversy associated with "the Happy Valley set"

The "Happy Valley set" was largely a group of hedonistic British and Anglo-Irish aristocrats and adventurers who settled in the Happy Valley region of the Wanjohi Valley near the Aberdare mountain range, in the colonies of Kenya and Uganda between the 1920s and the 1940s. From the 1930s the group became infamous for its decadent lifestyles and exploits following reports of drug use and sexual promiscuity.[5]

The area around Naivasha was one of the first to be settled in Kenya by white people and was one of the main hunting grounds of the 'set'. [6] The colonial town of Nyeri, Kenya, to the east of the Aberdare Range, was the centre of Happy Valley settlers. [7]

The white community in Kenya in the years before the Second World War was divided into two distinct factions: settlers, on the one side, and colonial officials and tradesmen, on the other. Both were dominated by upper-middle-class and upper-class British and Irish (chiefly Anglo-Irish) people, but the two groups often disagreed on important matters ranging from land allocation to how to deal with the natives. Typically, the officials and tradesmen looked on the Happy Valley set with embarrassment.

The height of the Happy Valley set's influence was in the late 1920s. The recession sparked by the 1929 Wall Street stock market crash greatly decreased the number of new arrivals to the Colony of Kenya and the influx of capital. Nevertheless, by 1939 Kenya had a white community of 21,000 people.

Some of the members (some described below) of the Happy Valley set were: The 3rd Baron Delamere and his son and heir The 4th Baron Delamere; The Hon. Denys Finch Hatton; The Hon. Berkeley Cole (an Anglo-Irish nobleman from Ulster); Sir Jock Delves Broughton, 11th Bt.; The 22nd Earl of Erroll; Lady Idina Sackville; Alice de Janzé (cousin of J. Ogden Armour); Frédéric de Janzé; Lady Diana Delves Broughton; Gilbert Colville; Hugh Dickenson; Jack Soames; Nina Soames; Lady June Carberry (stepmother of Juanita Carberry); Dickie Pembroke; and Julian Lezzard. Author Baroness Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen) had also been a friend of Lord Erroll.

In recent years, descendants of the Happy Valley set have been appearing in the news, particularly the legal troubles of The Hon. Tom Cholmondeley, the great-grandson of the famous Lord Delamere.

See also

References

- ↑ McGreal, Chris (26 October 2006). "A lost world". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ https://www.knbs.or.ke/ethnic-affiliation/

- ↑ "Brits Abroad: Country-by-country", BBC News, 11 December 2006, retrieved 2009-07-20

- ↑ "Eight months for Kenya aristocrat", BBC News, 14 May 2009, retrieved 2009-07-20

- ↑ Storm clouds over Happy Valley The Telegraph. 16 May 2009

- ↑ "Naivasha, Kenya" (tourist information), go2africa.com, 2006, webpage: Go2A.

- ↑ "Cultural Safari" (concerning Aberdare & Happy Valley settlers), MagicalKenya.com, webpage: MK.