Baguio

| Baguio Bag-iw | ||

|---|---|---|

| Highly Urbanized City | ||

| City of Baguio | ||

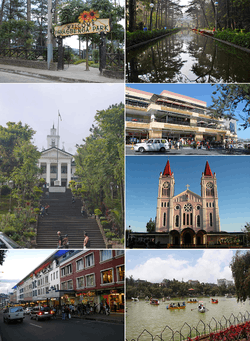

(From top, left to right): Panagbenga Park; Wright Park; Baguio City Hall; SM City Baguio; Baguio Cathedral; Session Road; Burnham Park Lake | ||

| ||

|

Nickname(s): Summer Capital of the Philippines City of Pines | ||

Map of Benguet with Baguio highlighted | ||

.svg.png) Baguio Location within the Philippines | ||

| Coordinates: 16°25′N 120°36′E / 16.42°N 120.6°ECoordinates: 16°25′N 120°36′E / 16.42°N 120.6°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Region | Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) | |

| Province | Benguet (geographically only) | |

| Districts | Lone district of Baguio City | |

| Founded | 1900 | |

| Incorporated | September 1, 1909 (city) | |

| Highly Urbanized City | December 22, 1979 | |

| Barangays | 129 | |

| Government | ||

| • Congressman | Marquez Go (LP) | |

| • Mayor | Mauricio Domogan (UNA) | |

| • Vice Mayor | Edison Bilog (LP) | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Highly Urbanized City | 57.51 km2 (22.20 sq mi) | |

| • Metro (BLISTT) | 1,094.79 km2 (422.70 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 1,540 m (5,050 ft) | |

| Population (2015 census)[2] | ||

| • Highly Urbanized City | 345,366 | |

| • Density | 6,000/km2 (16,000/sq mi) | |

| • Metro (BLISTT) | 551,764 | |

| • Metro density | 500/km2 (1,300/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) | Cordillerans | |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) | |

| ZIP code | 2600 | |

| PSGC | 141102000 | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)74 | |

| Climate | Cwb | |

| Income class | 1st city income class | |

| Revenue (₱) | 1,496,499,373.37 (2016) | |

| Languages | ||

| Highway routes |

| |

| Website |

www | |

Baguio, officially the City of Baguio (Ibaloi: Ciudad ne Bag-iw; Ilokano: Siudad ti Baguio; Filipino: Lungsod ng Baguio) and popularly referred to as Baguio City, is a mountain resort city located in Northern Luzon, Philippines. It is known as the Summer Capital of the Philippines, owing to its cool climate since the city is located approximately 4810 feet above mean sea level (1466 m) <maplogs.com> often cited as 1,540 meters (5,050 feet) in the Luzon tropical pine forests ecoregion, which also makes it conducive for the growth of mossy plants and orchids.[3]

Baguio is classified as a Highly Urbanized City (HUC). It is geographically located within Benguet, serving as the provincial capital from 1901 to 1916,[4] but has since been administered independently from the province following its conversion into a chartered city. The city is a highly urbanized area, a major center of business, commerce, and education in northern Luzon, as well as the location of the Cordillera Administrative Region.[5] According to the 2015 census, Baguio has a population of 345,366.[2]

Baguio was established as a hill station by the Americans in 1900 at the site of an Ibaloi village known as Kafagway. It was the United States' only hill station in Asia.[6] The name of the city is derived from bag-iw, the Ibaloi word for "moss".

History

Pre-colonial period

Baguio used to be a vast mountain zone with lush highland forests, teeming with various wildlife such as the indigenous deer, cloud rats, Philippine eagles, Philippine warty pigs, and numerous species of flora. The area was a hunting ground of the indigenous peoples, notably the Ibalois and other Igorot ethnic groups. During the 14th and 15th centuries, it was under the control of the Kingdom of Tondo until it returned to an indigenous plutocracy by the 16th century. When the Spanish arrived in the Philippines, the area was never fully subjugated by Spain due to the intensive defense tactics of the indigenous Igorots of the Cordilleras.

Spanish colonial period

During the period of Spanish rule in 1846, the Spaniards established a comandancia in the nearby town of La Trinidad, and organized Benguet into 31 rancherías, one of which was Kafagway, a wide grassy area where the present Burnham Park is situated. Kafagway was then a minor rancheria consisting of only about 20 houses. Most of the lands in Kafagway were owned by Mateo Cariño, who served as its chieftain.[7] The Spanish presidencia, which was located at Bag-iw at the vicinity of Guisad Valley was later moved to Cariño's house where the current city hall stands. Bag-iw, a local term for "moss" once abundant in the area was spelled by the Spaniards as Baguio, which served as the name of the rancheria.[4][8]

During the Philippine Revolution in July 1899, Filipino revolutionary forces under Pedro Paterno liberated La Trinidad from the Spaniards and took over the government, proclaiming Benguet as a province of the new Philippine Republic. Baguio was converted into a "town", with Mateo Cariño being the presidente (mayor).[4][8]

American colonial period

When the United States occupied the Philippines after the Spanish–American War, Baguio was selected to become the summer capital of the Philippine Islands. Governor-General William Taft, on his first visit in 1901, noted the "air as bracing as Adirondacks or Murray Bay... temperature this hottest month in the Philippines on my cottage porch at three in the afternoon sixty-eight."[9]:317–319

In 1903, Filipinos, Japanese and Chinese workers were hired to build Kennon Road, the first road directly connecting Baguio with the lowlands of Pangasinan. Before this, the only road to Benguet was Naguilian Road, and it was largely a horse trail at higher elevations. Camp John Hay was established on October 25, 1903 after President Theodore Roosevelt signed an executive order setting aside land in Benguet for a military reservation for the United States Army. It was named after Roosevelt's Secretary of State, John Milton Hay.

The Mansion, built in 1908, served as the official residence of the American Governor-General during the summer to escape Manila's heat. The Mansion was designed by architect William E. Parsons based on preliminary plans by architect Daniel Burnham.[10]

Burnham, one of the earliest successful modern city planners, designed the mountain retreat following the tenets of the City Beautiful movement.[11] In 1904, the rest of the city was planned out by Burnham. On 1 September 1909, Baguio was declared as a chartered city and nicknamed the "Summer Capital of the Philippines".[12]

The period after saw further development of Baguio with the construction of Wright Park in honor of Governor-General Luke Edward Wright, Burnham Park in honor of Burnham, Governor Pack Road, and Session Road.[13]

World War II

Prior to World War II, Baguio was the summer capital of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, and the home of the Philippine Military Academy.[14]

Following the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army used Camp John Hay, an American installation in Baguio, as a military base.[15] The nearby Philippine Constabulary base, Camp Holmes, was used as an internment camp for about 500 civilian enemy aliens, mostly Americans, between April 1942 and December 1944.[16]

By late March 1945, Baguio was within range of the American and Filipino military artillery. President José P. Laurel of the Second Philippine Republic, a puppet state established in 1943, departed the city on 22 March and reached Taiwan eight days later, on 30 March.[17] The remainder of the Second Republic government, along with Japanese civilians, were ordered to evacuate Baguio on March 30. General Tomoyuki Yamashita and his staff then relocated to Bambang, Nueva Vizcaya.[18]

A major offensive to capture Baguio did not occur until mid-April, when the United States Army's 37th Infantry Division, minus the 145th Infantry Regiment, was released from garrisoning Manila to launch a two-division assault into Baguio from the west and south.

On 26 April 1945, Filipino troops of the 1st, 2nd, 12th, 13th, 15th and 16th Infantry Division of the Philippine Commonwealth Army, 1st Constabulary Regiment of the Philippine Constabulary and the USAFIP-NL 66th Infantry Regiment and the American troops of the 33rd and 37th Infantry Division of the United States Army entered Baguio and fought against Japanese Imperial Army forces led by General Yamashita, which started the Battle of Baguio.

Baguio is the site of the formal surrender of General Yamashita and Vice Admiral Okochi at Camp John Hay's American Residence in the presence of lieutenant generals Arthur Percival and Jonathan Wainwright.[19]

1990 earthquake

The 1990 Luzon earthquake (Ms = 7.7) destroyed some parts of Baguio and the surrounding province of Benguet on the afternoon of July 16, 1990.[20] A significant number of buildings and infrastructure were damaged, including the Hyatt Terraces Plaza, Nevada Hotel, Baguio Park Hotel, FRB Hotel and Baguio Hilltop Hotel; major highways were temporarily blocked due to landslides and pavement breakup; and a number of houses were leveled or severely shaken with shocking losses of life, according to a Wiki-editor with ties to Baguio since May 1975, and [21] Some of the fallen buildings were built on or near fault lines; local architects later admitted structural building codes should have been followed more religiously, particularly regarding concrete and rebar standards, and "soft stories." Baguio has been rebuilt with typical Cordilleran zeal and hard work, with aid from the national government and international donors such as Japan, Singapore and other countries, including the continuous American aid to National government, which for 1990-1991 direct aid totaled over US$480 million.

Geography

Baguio is located some 1,540 meters (5,050 feet) above sea level, nestled within the Cordillera Central mountain range in northern Luzon. The city is enclosed by the province of Benguet. It covers a small area of 57.5 square kilometres (22.2 sq mi). Most of the developed part of the city is built on uneven, hilly terrain of the northern section. When Daniel Burnham drew plans for the city, he made the City Hall a reference point where the city limits extend 8.2 kilometres (5.1 mi) from east to west and 7.2 kilometres (4.5 mi) from north to south.

Barangays

Baguio is politically subdivided into 129 barangays.[22]

- A. Bonifacio-Caguioa-Rimando (ABCR)

- Abanao-Zandueta-Kayong-Chugum-Otek (AZKCO)

- Alfonso Tabora

- Ambiong

- Andres Bonifacio (Lower Bokawkan)

- Apugan-Loakan

- Asin Road

- Atok Trail

- Aurora Hill Proper (Malvar-Sgt. Floresca)

- Aurora Hill, North Central

- Aurora Hill, South Central

- Bagong Lipunan (Market Area)

- Bakakeng Central

- Bakakeng North

- Bal-Marcoville (Marcoville)

- Balsigan

- Bayan Park East

- Bayan Park Village

- Bayan Park West (Bayan Park, Leonila Hill)

- BGH Compound

- Brookside

- Brookspoint

- Cabinet Hill-Teacher's Camp

- Camdas Subdivision

- Camp 7

- Camp 8

- Camp Allen

- Campo Filipino

- City Camp Central

- City Camp Proper

- Country Club Village

- Cresencia Village

- Dagsian, Lower

- Dagsian, Upper

- Dizon Subdivision

- Dominican Hill-Mirador

- Dontogan

- DPS Compound

- Engineers' Hill

- Fairview Village

- Ferdinand (Happy Homes-Campo Sioco)

- Fort del Pilar

- Gabriela Silang

- General Emilio F. Aguinaldo (Quirino‑Magsaysay, Lower)

- General Luna, Upper

- General Luna, Lower

- Gibraltar

- Greenwater Village

- Guisad Central

- Guisad Sorong

- Happy Hollow

- Happy Homes (Happy Homes-Lucban)

- Harrison-Claudio Carantes

- Hillside

- Holy Ghost Extension

- Holy Ghost Proper

- Honeymoon (Honeymoon-Holy Ghost)

- Imelda R. Marcos (La Salle)

- Imelda Village

- Irisan

- Kabayanihan

- Kagitingan

- Kayang Extension

- Kayang-Hilltop

- Kias

- Legarda-Burnham-Kisad

- Liwanag-Loakan

- Loakan Proper

- Lopez Jaena

- Lourdes Subdivision Extension

- Lourdes Subdivision, Lower

- Lourdes Subdivision, Proper

- Lualhati

- Lucnab

- Magsaysay Private Road

- Magsaysay, Lower

- Magsaysay, Upper

- Malcolm Square-Perfecto (Jose Abad Santos)

- Manuel A. Roxas

- Market Subdivision, Upper

- Middle Quezon Hill Subdivision (Quezon Hill Middle)

- Military Cut-off

- Mines View Park

- Modern Site, East

- Modern Site, West

- MRR-Queen of Peace

- New Lucban

- Outlook Drive

- Pacdal

- Padre Burgos

- Padre Zamora

- Palma-Urbano (Cariño-Palma)

- Phil-Am

- Pinget

- Pinsao Pilot Project

- Pinsao Proper

- Poliwes

- Pucsusan

- Quezon Hill Proper

- Quezon Hill, Upper

- Quirino Hill, East

- Quirino Hill, Lower

- Quirino Hill, Middle

- Quirino Hill, West

- Quirino-Magsaysay, Upper (Upper QM)

- Rizal Monument Area

- Rock Quarry, Lower

- Rock Quarry, Middle

- Rock Quarry, Upper

- Saint Joseph Village

- Salud Mitra

- San Antonio Village

- San Luis Village

- San Roque Village

- San Vicente

- Sanitary Camp, North

- Sanitary Camp, South

- Santa Escolastica

- Santo Rosario

- Santo Tomas Proper

- Santo Tomas School Area

- Scout Barrio

- Session Road Area

- Slaughter House Area (Santo Niño Slaughter)

- SLU-SVP Housing Village

- South Drive

- Teodora Alonzo

- Trancoville

- Victoria Village

Proposed merger of barangays

A proposed merging of the city's 128 barangays had not been implemented since its inception in 2000. Several local officials stressed that many of the city's barangays did not comply with the minimum requirements in the Local Government Code of the Philippines that a highly urbanized city must have a certified population of least 5,000 inhabitants. According to Mayor Mauricio Domogan, in the past, benefits granted to local governments were based on the number of existing barangays. This led former local officials to create as many barangays as possible in the city in order to acquire additional benefits from the national government. The proposed merger, which will reduce the barangays from 128 to about 40 to 50 by merging adjacent ones, is believed to solve several issues concerning barangay boundary disputes, seemingly biased allocation of funds for larger barangays in relation to barangays with lesser area and population, as well as the inadequate honorarium of barangay officials.[23][24][25]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Baguio features a subtropical highland climate (Cwb)[26] that closely borders a tropical monsoon climate (Am). The city is known for its mild climate owing to its high elevation. The temperature in the city is usually about 7 to 8 °C (12.6 to 14.4 °F) cooler than the temperature in the lowland area.[27] Average temperature ranges from 15 to 23 °C (59 to 73 °F) with the lowest temperatures between November and February. The lowest recorded temperature was 6.3 °C (43.3 °F) on January 18, 1961 and in contrast, the all-time high of 30.4 °C (86.7 °F) was recorded on March 15, 1988 during the 1988 El Niño season.[28] The temperature seldom exceeds 26 °C (78.8 °F) even during the warmest part of the year.

Precipitation

Like many other cities with a subtropical highland climate, Baguio receives noticeably less precipitation during its dry season. However, the city has an extraordinary amount of precipitation during the rainy season with the months of July and August having, on average, more than 700 mm (28 in) of rain. The city averages over 3,100 mm (122 in) of precipitation annually.

| Climate data for Baguio (1981–2010, extremes 1909–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.7 (85.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.0 (86) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.0 (77) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.9 (75) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

15.1 (59.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.3 (43.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.0 (50) |

7.7 (45.9) |

N/A | 12.5 (54.5) |

12.8 (55) |

12.6 (54.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 15.2 (0.598) |

23.4 (0.921) |

46.0 (1.811) |

104.1 (4.098) |

341.1 (13.429) |

475.8 (18.732) |

781.9 (30.783) |

905.0 (35.63) |

570.9 (22.476) |

454.3 (17.886) |

97.4 (3.835) |

26.2 (1.031) |

3,841.4 (151.236) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 3 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 20 | 22 | 26 | 27 | 24 | 17 | 8 | 4 | 168 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85 | 84 | 83 | 84 | 88 | 89 | 92 | 93 | 91 | 89 | 86 | 84 | 87 |

| Source: PAGASA[29][30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Population census of Baguio | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1918 | 5,464 | — |

| 1939 | 24,117 | +7.33% |

| 1948 | 29,262 | +2.17% |

| 1960 | 50,436 | +4.64% |

| 1970 | 84,538 | +5.29% |

| 1975 | 97,449 | +2.89% |

| 1980 | 119,009 | +4.08% |

| 1990 | 183,142 | +4.41% |

| 1995 | 226,883 | +4.09% |

| 2000 | 252,386 | +2.31% |

| 2007 | 301,926 | +2.50% |

| 2010 | 318,676 | +1.98% |

| 2015 | 345,366 | +1.54% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[2] [31] [32] [33] | ||

The city’s population as of May 2000 was placed at 250,000 persons. The city has a very young age structure as 65.5 percent of its total population is below thirty years old. Females comprise 51.3 percent of the population as against 48.7 percent for males. The household population comprises 98 percent of the total population or 245000 persons. With an average of 4.6 members per household, a total of 53,261 household are gleaned. During the peak of the annual tourist influx, particularly during the Lenten period, transients triple the population.[12]

Religion

The majority of Baguio's population are Roman Catholics. Other Christian denominations and sects in the city include the Pentecostal Missionary Church of Christ (4th Watch), Episcopal Church, Iglesia ni Cristo, Iglesia Filipina Independiente, Jehovah's Witnesses, United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), Jesus Is Lord Church (JIL), Jesus Miracle Crusade (JMC), the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), the United Methodist Church, Assemblies of God (AG), and Baptist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Members Church of God International (MCGI), Bible Fundamental, and other Evangelical churches.

There is also a significant number of Muslims in the cities, consisting of Filipino Muslims of different ethnicities and Muslims of other nationalities. The largest mosque in the area is Masjid Al-Maarif, which is a known centre of Islamic studies in the Philippines. The city also has smaller numbers of Buddhists and atheists, along with members of other faiths.

Economy

(2018-02-25).jpg)

Baguio is the melting pot of different peoples and cultures in the Cordillera Administrative Region. Because of this, numerous investments and business opportunities are lured to the city.[12] Baguio has a large retail industry, with shoppers coming to the city to take advantage of the diversity of competitively priced commercial products on sale.[34] The city is also popular with bargain hunters—some of the most popular bargaining areas include Baguio Market and Maharlika Livelihood Center. Despite the city's relatively small size, it is home to numerous shopping centers and malls catering to increasing commercial and tourist activity in Baguio: these include SM City Baguio, Baguio Center Mall, Cooyeesan Hotel Plaza, Abanao Square, The Maharlika Livelihood Center, Porta Vaga Mall and Centerpoint Plaza.

Various food and retail businesses run by local residents proliferate, forming a key part of Baguio's cultural landscape. Several retail outlets and dining outlets are situated along Bonifacio Street, Session Road, near Teacher's Camp, and Baguio Fastfood Center near the market.

The areas of Session Road, Harrison Road, Magsaysay Avenue and Abanao Street comprise the trade center of the city, where commercial and business structures such as cinemas, hotels, restaurants, department stores, and shopping centers are concentrated. The City Market offers a wide array of locally sourced goods and products, usually from Benguet province,[35][36] which includes colorful woven fabrics and hand-strung beads to primitive wood carvings, cut flowers,[35] strawberries and "Baguio" vegetables, the latter often denoting vegetable types that do well in the cooler growing climate. (Strawberries and string beans—referred to as Baguio beans across the Philippines—are shipped to major urban markets across the archipelago.)

Another key source of income for Baguio is its position as the commercial hub for the province of Benguet. Many agricultural and mining goods produced in Benguet pass through Baguio for processing, sale or further distribution to the "lowlands".

Industrial

Baguio is one of the country's most profitable and best investment areas.[37][38]

A Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA)-accredited business and industrial park called the Baguio City Economic Zone (BCEZ) is located in the southern part of the city between Camp John Hay Country Club and Philippine Military Academy in Barangay Loakan. Firms located in the BCEZ mostly produce and export knitted clothing, transistors, small components for vehicles, electronics and computer parts. Notable firms include Texas Instruments Philippines, which is the second largest exporter in the country.[39] Other companies headquartered inside the economic zone are Moog Philippines, Inc., Linde Philippines, Inc., LTX Philippines Corporation, Baguio-Ayalaland Technohub, and Sitel Philippines, Baguio.

Outsourcing

Outsourcing also contributes to the city's economy and employment. There are many call centers present in the city. Teleperformance Baguio is headquartered in front of Sunshine Park.

Other call centers in downtown are Optimum Transsource, Sterling Global and Global Translogic. While others like Convergys and IHG (InterContinental Hotels Group) have call centers in Camp John Hay away from the city proper. Tech-Synergy operates a large transcription and backoffice operation near Wright park. SitelThoughtFocus Technologies, a leading US provider of Software and KPO services decided to set up its KPO operation center in Baguio.

Culture

The languages commonly spoken in Baguio are Ibaloi, Kankana-ey and Ifugao, as well as Ilocano, Pangasinan and Kapampangan. Tagalog and English are also understood by many inhabitants within and around the city.

The Panagbenga Festival, the annual Flower Festival, is celebrated each February to showcase Baguio's rich cultural heritage, its appreciation of the environment, and inclination towards the arts. The indigenous people were initially wary with government-led tourism due to a perceived threat that the government would interfere with or change their communities' rituals.[40]

The city became a haven for many Filipino artists in the 1970s–1990s. Drawn by the cool climate and low cost of living, artists such as Ben Cabrera (now a National Artist) and filmmaker Butch Perez relocated to the city. At the same time, locals such as mixed-media artist Santiago Bose and filmmaker Kidlat Tahimik were also establishing work in the city. Even today, artists like painters and sculptors from all over the country are drawn to the Baguio Arts Festival which is held annually.[27]

Baguio has been included in UNESCO's Creative Cities Network due to craft and folk art traditions of the city.[41] The city is the first city to be part of the inter-city network which aims to promote the creative industries as well as integrate culture in sustainable urban development.[42]

Tourism

Tourism is one of Baguio's main industries due to its cool climate and history. The city is one of the country's top tourist destinations. During the year end holidays some people from the lowlands prefer spending their vacation in Baguio, to experience cold temperatures they rarely have in their home provinces. Also, during summer, especially during Holy Week, tourists from all over the country flock to the city. During this time, the total number of people in the city doubles.[43] To accommodate all these people there are more than 80 hotels and inns available.[44] Local festivities such as the Panagbenga Festival also attracts both local and foreign tourists.

Baguio is the lone Philippine destination in the 2011 TripAdvisor Traveller's Choice Destinations Awards (Asia category) with the city being among the top 25 destinations in Asia.[45] The Burnham Park, Mines View Park, Teacher's Camp, and Baguio Cathedral are among the top tourist sites in Baguio.

Local government

(2018-02-25).jpg)

Like most Philippine cities, Baguio is governed by a mayor, vice mayor, and 12 councilors. However, as a highly urbanized city with its own charter, it is not subject to the jurisdiction of Benguet province, of which it was formerly a part. The current mayor of Baguio is Mauricio Domogan, and the lone congressional district is currently represented by Congressman Mark Go. They were elected in May 2016.

Sports

The Baguio Athletic Bowl within the grounds of Burnham Park is one of Baguio's primary sporting venues. Baguio has also hosted the 1978 World Chess Championship match between Anatoly Karpov and Viktor Korchnoi.

Transportation

Air

Loakan Airport is the lone airport serving the general area of Baguio. The airport is classified as a trunkline airport, or a major commercial domestic airport, by the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines but there are currently no regular commercial services in the airport. It is located south of the city center. Due to the limited length of the runway which is 1,802 meters or 5,912 feet, it is restricted to commuter size aircraft. The airport is used primarily by helicopters, turbo-prop and piston engine aircraft, although on rare occasion light business jets (LBJ) have flown into the airport.

Land

The three main access roads leading to Baguio from the lowlands are Kennon Road (formerly known as the Benguet Road),[46] Aspiras–Palispis Highway (previously known as Marcos Highway)[47] and Naguilian Road, also known as Quirino Highway. Kennon Road starts at Rosario, La Union and winds upwards through a narrow, steep valley. This is often the fastest route to Baguio but it is particularly perilous,[46] with landslides during the rainy season and sharp dropoffs, some without guardrails.

The Aspiras Highway, which starts in Agoo, La Union and connects to Palispis Highway, at the boundary of Benguet and La Union provinces, and Naguilian Road, which starts in Bauang, La Union, are both longer routes but are much safer than Kennon Road especially during rainy season, and are the preferred routes for coaches, buses and trucks.

The Benguet-Nueva Vizcaya Road, which links Baguio to Aritao in Nueva Vizcaya province, traverses the towns of Itogon, Bokod, and Kayapa.[48]

Another road, Halsema Highway, (also known as the Baguio-Bontoc Road or the Mountain Trail) leads north through the mountainous portion of the provinces of Benguet and Mountain Province.[49] It starts at the northern border of Baguio with La Trinidad.

There are several bus lines linking Baguio with Manila and Central Luzon, and provinces such as Pangasinan, Nueva Ecija, Aurora, Cavite, La Union, and those in the Ilocos regions. Taxis and jeepneys are common forms of transportation in the city.

Education

Baguio is a university town with 141,088 students out of the 301,926 population count done in the year 2007. It is the center of education in the entire North Luzon. There are eight major institutions of higher education in Baguio: the Saint Louis University, University of the Philippines Baguio, Philippine Military Academy, University of Baguio, University of the Cordilleras, Baguio Central University, Pines City Colleges, and Easter College.[50]

Notable people

Sister cities

Local

- Angeles, Pampanga[51]

- Alaminos, Pangasinan[51]

- Bacolod, Negros Occidental[51]

- Calbayog, Samar[51]

- Candon[52]

- Daet, Camarines Norte[51]

- Davao City[51]

- Dipaculao, Aurora[51]

- Lopez, Quezon[51]

- Lucena, Quezon[51]

- Makati, Metro Manila[51]

- Mandaue, Cebu[51]

- Marawi[51]

- Muñoz, Nueva Ecija[51]

- Ormoc, Leyte[51]

- Pavia, Iloilo[51]

- San Carlos, Negros Occidental[51]

- Zamboanga City[51]

International

See also

References

- ↑ "Province: Benguet". PSG0C Interactive. Makati City, Philippines: National Statistical Coordination Board. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 Census of Population (2015). "Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ "Southeastern Asia: Island of Luzon in the Philippines". WWF. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Sanidad, Pablito. "Which Baguio Centennial?" (99th Baguio Charter Day Anniversary Issue). Baguio Midland Courier. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.baguio.gov.ph/?q=content/business-0

- ↑ Estoque, Ronald C.; Yuji Murayama (February 2013). "City Profile: Baguio". Cities. 30: 240–51. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2011.05.002.

- ↑ Boquiren, Rowena Reyes (23 Aug 2015). "Baguio's history and cultural heritage". Northern Dispatch Weekly. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- 1 2 "Baguio City; History and Government". Department of the Interior and Local Government - Cordillera Administrative Region. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Kane, S.E., 1933, Life and Death in Luzon or Thirty Years with the Philippine Head-Hunters, New York: Grosset & Dunlap

- ↑ Cody, Jeffrey W. (2003). "Exporting American Architecture, 1870–2000", pg. 23. Alexandrine Press, Oxford; ISBN 0-203-98658-X.

- ↑ Galang, Willie (23 January 2010). "Mansion House (NHI Marker)". Flickr.com; retrieved 21 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 "About Baguio City". City Government of Baguio. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Americans in Baguio". Go Baguio:Your Complete Guide to Baguio City, Philippines. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ Sakakida, Richard; Kiyosaki, Wayne S. (3 July 1995). A Spy in Their Midst: The World War II Struggle of a Japanese-American Hero. Madison Books. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4616-6286-0.

- ↑ "Flowers, new song for 72nd year of Baguio war bombings". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ Forbidden Diary: A Record of Wartime Internment, 1941–1945 by Natalie Crouter (Burt Franlin & Co. 1980)

- ↑ Jose, Ricardo T. "Government in Exile" (PDF). Scalabrini Migration Center. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Zeiler, Thomas W. (2004). Unconditional Defeat: Japan, America, and the End of World War II. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8420-2991-9.

- ↑ General Staff of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (1966). "Chapter XIV: Japan's Surrender". Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaign of MacArthur in the Pacific, Volume I. United States Army. p. 464. ISBN 978-1-78266-035-4. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

"The American Residence in Baguio". Embassy of the United States, Manila, Philippines. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

Farrell, Brian; Hunter, Sandy (15 December 2009). A Great Betrayal: The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. p. 163. ISBN 9789814435468.

Tucker, Spencer (21 November 2012). Almanac of American Military History, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 1727. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3. - ↑ Punongbayan, Raymundo S.; Rimando, Rolly E.; Daligdig, Jessie A.; Besana, Glenda M.; Daag, Arturo S.; Nakata, Takashi; Tsutsumi, Hiroyuki. "The July 16 Earthquake; A Technical Monograph". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology; Hiroshima University. Archived from the original on 7 Oct 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ Gwen de la Cruz (16 July 2014). "Remembering the 1990 Luzon Earthquake". rappler.com. Rappler. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ↑ "Baguio City}". Department of the Interior and Local Government, Cordillera Administrative Region. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ See, Dexter A. "Merger of city's 128 barangays pressed". Official website of the City Government of Baguio. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ "Special body formed for barangay merger". Sun.Star Philippines. 8 Mar 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ Cruz, Maria Aprila W. "More dialogues on merger of barangay pressed". Baguio Midland Courier. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ "Climate: Baguio – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- 1 2 "Baguio City Travel Information, Philippines". Asia Travel. Retrieved 2013-02-26.

- ↑ Basilan, Jacquelyn; Khristine Love Vicente (17 December 2008). "Baguio wakes up to coldest morn in 2008". Breaking News / Regions. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ "Baguio City, Benguet Climatological Normal Values". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ "Baguio City, Benguet Climatological Extremes". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ↑ Censuses of Population (1903–2007). "Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)". Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Province/Highly Urbanized City: 1903 to 2007. NSO.

- ↑ "Province of Benguet". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "How small malls compete with big malls". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- 1 2 Sinumlag, Alma B. (28 November 2010). "LT folk clarifies Baguio cut flowers origin". Northern Dispatch Weekly. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

The spokesperson of this town’s Municipal Agricultural and Fishery Council (MAPC) and chairperson of the Barangay Agricultural and Fishery Council (BAPC) in Lubas, La Trinidad clarified that cut flowers do not really originate in Baguio. Christina Tiongan in an interview on 24 November lamented that tourists always associate Baguio with cut flowers and other products like temperate vegetables that do not really originate in the city. “We are the ones producing those products but there had been no efforts from the city to correct tourists' perception”, she said.

- ↑ Lapniten, Karl (24 February 2016). "Strawberries hit bottom prices in Baguio". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

The capital town of Benguet, La Trinidad supplies most of the strawberries sold at the Baguio Public Market. Much of the produce also comes from small strawberry farms in the outskirts of Baguio and in nearby municipalities of Benguet.

- ↑ "Baguio offers investors new profit opportunities". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "Business booms in Baguio City as 18th Ad Congress draws near". Philsatr Business. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ Cahiles-Magkilat, Bernie (13 February 2007). "Baguio export zone to get P6.7 B in new investments". Manila Bulletin Publishing Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Cabreza, Vincent (26 January 2008). "Cordillera tribes realize why they should not fear tourism". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ↑ "Baguio is Philippines' first UNESCO 'creative city'". cnn. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ↑ "Baguio hailed as a UNESCO 'creative city'". ABS-CBN News. 1 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ "--- Statistics: Tourism Special Tables ---". nscb.gov.ph.

- ↑ "Complete list of Baguio Hotels". philippines-travel-guide.com.

- ↑ "Best Destinations in Asia - Travelers' Choice Awards - TripAdvisor". tripadvisor.com.

- 1 2 Cabreza, Vincent (16 May 2012). "Fighting for century-old Kennon Road". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Inquirer Northern Luzon. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

The colonial government decided then that constructing the Benguet Road (Kennon Road’s original name) would provide the Americans a short route up the Benguet mountains. ... When Baguio was devastated by the July 16, 1990 earthquake, then Public Works Secretary Gregorio Vigilar decided to permanently close the damaged Kennon Road, said Cosalan. The government discovered 471 “disaster spots” along the route, which the Mines and Geosciences Bureau attributed to the fragility of the rock base, the abandoned mining operations near the road and the natural ground fractures that were undetectable in the 1900s.

- ↑ "Republic Act No. 8971; An Act Naming the Agoo-Tubao-Pugo Section of the Agoo-Baguio Road, the Jose D. Aspiras Highway, and the Benguet-Baguio City Section of the Same Road, the Ben Palispis Highway". Chan Robles Virtual Law Library. 31 October 2000. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ Lagasca, Charlie (14 March 2006). "Vizcaya-Benguet road completed this year". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

BAYOMBONG, Nueva Vizcaya - Novo Vizcayanos can now look forward to reaching the country's summer capital in a few hours as the shortest route linking this landlocked province to the mountain city is expected to be completed by the end of this year. ... The new route will traverse the mountain highway from Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya to Baguio via the vegetable-rich upland town of Kayapa and the majestic Ambuklao Dam in Bokod, Benguet.

- ↑ Caluza, Desiree (26 May 2014). "Mountain Trail leads to culture, nature hubs". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Inquirer Northern Luzon. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

BAGUIO CITY, Philippines—Travelers who often frequent the 165-kilometer Mountain Trail may have gotten so used to the view along the scenic route that they often doze off all throughout the trip along this highway linking the provinces of Benguet, Mountain Province and Ifugao in the Cordillera. ... While the road length stretches to only a little more than 100 kilometres (62 miles) from La Trinidad town in Benguet to the Mountain Province capital of Bontoc, those raring for adventure and new sights should be prepared to spend six hours on the road.

- ↑ Basoyang, Marianne K. "History of Easter College". Easter College. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Dacuag, Pearl A. (6 Sep 2009). "20 sister cities pledge to fortify ties with Baguio". Baguio Midland Courier. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ "Marvil: Baguio and Candon City Sign Sisterhood MOU".

- ↑ "Honolulu Data: Sister Cities" (official website). Honolulu: City and County of Honolulu. 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ↑ See, Dexter A. (2014-10-24). "Twinning ties for Baguio and Nazareth". The Standard. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Vallejo's Sister Cities". Vallejo Sister Cities Association. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baguio. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baguio. |

(2018-02-25).jpg)