Promethazine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Many[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682284 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral, rectal, IV, IM, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 88% absorbed but after first-pass metabolism reduced to 25% absolute bioavailability[2] |

| Protein binding | 93% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic glucuronidation and sulfoxidation |

| Elimination half-life | 16–19 hours[2][3] |

| Excretion | Renal and biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.000.445 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

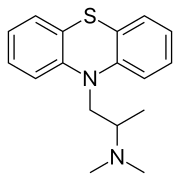

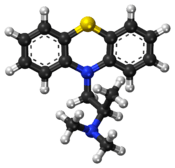

| Formula | C17H20N2S |

| Molar mass | 284.42 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Promethazine is a first-generation antihistamine of the phenothiazine family. The drug has strong sedative and weak antipsychotic effects. It also reduces motion sickness and has antiemetic (Histamine H1 receptors but it does not block the production of histamine) and anticholinergic properties. In some countries it is prescribed for insomnia when benzodiazepines are contraindicated. It is available in many countries under many brand names.[1][4] Promethazine was developed in the mid 1940s when a team of scientists from Rhône-Poulenc laboratories were able to synthesize it from phenothiazine.[5]

Medical uses

Promethazine has a variety of medical uses, including:

- As a sedative[6]

- For preoperative sedation and to counteract postnarcotic nausea[6]

- To reduce nervousness, restlessness and agitation caused by psychiatric conditions (used for this purpose mainly in Europe)

- As antiallergic medication to combat hay fever (allergic rhinitis), etc., or to treat allergic reactions, alone or in combination with oral decongestants such as pseudoephedrine[6]

- As an adjunct treatment for anaphylactoid conditions (IM/IV route preferred)[6]

- Together with codeine or dextromethorphan against cough

- As a motion sickness or seasickness remedy when used with ephedrine or pseudoephedrine[6]

- To combat moderate to severe morning sickness and hyperemesis gravidarum: In the UK, promethazine is drug of first choice, being preferred as an older drug with which there is a greater experience of use in pregnancy (second in line being metoclopramide or prochlorperazine).[7]

- Previously, it was used as an antipsychotic,[8] although it is generally not administered for this purpose now; promethazine has only approximately 1/10 of the antipsychotic strength of chlorpromazine.

- Treatment for migraines; however, other similar medications, like Compazine, have been shown to have a more favorable treatment profile,[9] and are used almost exclusively over promethazine.

Side effects

Some documented side effects include:

- Tardive dyskinesia (effects due to dopamine D2 receptor antagonism)

- Confusion in the elderly

- Drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, more rarely vertigo

- Dry mouth

- Respiratory depression in patients under age of two and in those with severely compromised pulmonary function

- Constipation

- Chest discomfort/pressure (typically in cases when patient is already taking medication for high blood pressure)

- Akathisia [10]

- Paresthesia

- Short temper/irritability

Extremely rare side effects include:

- Seizures

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- Euphoria (very rare, except with high IV doses and/or coadministration with opioids/CNS depressants)

Because of potential for more severe side effects, this drug is on the list to avoid in the elderly.[11] In many countries (including the US and UK), promethazine is contraindicated in children less than two years of age, and strongly cautioned against in children between two and six, due to problems with respiratory depression and sleep apnea.[12]

Promethazine is listed as one of the drugs of highest anticholinergic activity in a study of anticholinergenic burden, including long-term cognitive impairment.[13]

Pharmacology

Promethazine, a phenothiazine derivative, is structurally different from the neuroleptic phenothiazines, with similar but different effects.[2] It acts primarily as a strong antagonist of the H1 receptor (antihistamine) and a moderate mACh receptor antagonist (anticholinergic),[2] and also has weak to moderate affinity for the 5-HT2A,[14] 5-HT2C,[14] D2,[15][16] and α1-adrenergic receptors,[17] where it acts as an antagonist at all sites, as well.

Another notable use of promethazine is as a local anesthetic, by blockade of sodium channels.[17]

Chemistry

Solid promethazine hydrochloride is a white to faint-yellow, practically odorless, crystalline powder. Slow oxidation may occur upon prolonged exposure to air, usually causing blue discoloration. Its hydrochloride salt is freely soluble in water and somewhat soluble in alcohol. Promethazine is a chiral compound, occurring as a mixture of enantiomers.[18]

History

Promethazine was first synthesized by a group at Rhone-Poulenc (which later became part of Sanofi) led by Paul Charpentier in the early 1940s.[19] The team was seeking to improve on diphenhydramine; the same line on medical chemistry led to the creation of chlorpromazine.[20]

Society and culture

As of July 2017 it was marketed under many brand names worldwide: Allersoothe, Antiallersin, Anvomin, Atosil, Avomine, Closin N, Codopalm, Diphergan, Farganesse, Fenazil, Fenergan, Fenezal, Frinova, Hiberna, Histabil, Histaloc, Histantil, Histazin, Histazine, Histerzin, Lenazine, Lergigan, Nufapreg, Otosil, Pamergan, Pharmaniaga, Phenadoz, Phenerex, Phenergan, Phénergan, Pipolphen, Polfergan, Proazamine, Progene, Prohist, Promet, Prometal, Prometazin, Prometazina, Promethazin, Prométhazine, Promethazinum, Promethegan, Promezin, Proneurin, Prothazin, Prothiazine, Prozin, Pyrethia, Quitazine, Reactifargan, Receptozine, Romergan, Sominex, Sylomet, Xepagan, Zinmet, and Zoralix.[1]

It is also marketed in many combination drug formulations:

- with carbocisteine as Actithiol Antihistaminico, Mucoease, Mucoprom, Mucotal Prometazine, and Rhinathiol;

- with paracetamol as Algotropyl, Calmkid, Fevril, Phen Plus, and Velpro-P;

- with paracetamol and dextromethorphan as Choligrip na noc, Coldrex Nočná Liečba, Fedril Night Cold and Flu, Night Nurse, and Tachinotte;

- with paracetamol, phenylephrine, and salicylamide as Flukit;

- with dextromethorphan as Axcel Dextrozine and Hosedyl DM;

- with dextromethorphan and ephedrine as Methorsedyl;

- with dextromethorphan and pseudoephedrine as Sedilix-DM;

- with dextromethorphan and phenylephedrine as Sedilix-RX;

- with pholcodine as Codo-Q Junior and Tixylix;

- with pholcodine and ephedrine as Phensedyl Dry Cough Linctus;

- with pholcodine and phenylephedrine as Russedyl Compound Linctus;

- with pholcodine and phenylpropanolamine as Triple 'P';

- with codeine as Kefei and Procodin;

- with codeine and ephedrine as Dhasedyl, Fendyl, and P.E.C. ;

- with ephedrine and dextromethorphan as Dhasedyl DM;

- with glutamic acid as Psico-Soma, and Psicosoma;

- with noscapine as Tussisedal; and

- with chlorpromazine as Vegetamin.[1]

Product liability lawsuit

In 2009, the US Supreme Court ruled on a product liability case involving promethazine. Diana Levine, a woman suffering from a migraine, was administered Wyeth's Phenergan via IV push. The drug was injected improperly, resulting in gangrene and subsequent amputation of her right forearm below the elbow. A state jury awarded her $6 million in punitive damages.

The case was appealed to the Supreme Court on grounds of federal preemption and substantive due process.[21] The Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' rulings, stating that "Wyeth could have unilaterally added a stronger warning about IV-push administration" without acting in opposition to federal law.[22] In effect, this means drug manufacturers can be held liable for injuries if warnings of potential adverse effects, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), are deemed insufficient by state courts.

On September 9, 2009, the FDA required a boxed warning be put on promethazine for injection, stating the contraindication for subcutaneous administration. The preferred administrative route is intramuscular, which reduces risk of surrounding muscle and tissue damage.[23]

See also

- Purple drank (a recreational drug concoction containing promethazine)

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Promethazine international brands". Drugs.com. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Strenkoski-Nix LC, Ermer J, DeCleene S, Cevallos W, Mayer PR (August 2000). "Pharmacokinetics of promethazine hydrochloride after administration of rectal suppositories and oral syrup to healthy subjects". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 57 (16): 1499–505. PMID 10965395.

- ↑ Paton DM, Webster DR (1985). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of H1-receptor antagonists (the antihistamines)". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 10 (6): 477–97. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510060-00002. PMID 2866055.

- ↑ RxList: Promethazine

- ↑ Li, Jie Jack (2006). Laughing Gas, Viagra, and Lipitor: The Human Stories behind the Drugs We Use. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780199885282. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 RxList Indications for Promethazine

- ↑ British National Formulary (March 2001). "4.6 Drugs used in nausea and Vertigo - Vomiting of pregnancy". BNF (45 ed.). .

- ↑ (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20110718172715/http://www.cja-jca.org/cgi/reprint/6/4/375.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2008. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Callan JE, Kostic MA, Bachrach EA, Rieg TS (Oct 2008). "Prochlorperazine vs. promethazine for headache treatment in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial". J Emerg Med. 35 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.047. PMID 18534808.

- ↑ Cordingley Neurology

- ↑ NCQA’s HEDIS Measure: Use of High Risk Medications in the Elderly Archived 2010-02-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Starke P, Weaver J, Chowdhury B (2005). "Boxed warning added to promethazine labeling for pediatric use". N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (5): 2653. doi:10.1056/nejm200506233522522.

- ↑ Salahudeen MJ; Duffull SB; Nishtala PS; et al. (2015-03-25). "Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: a systematic review". BMC Geriatrics. 15 (31): 31. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0029-9. PMC 4377853. PMID 25879993.

- 1 2 Fiorella D, Rabin RA, Winter JC (October 1995). "The role of the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in the stimulus effects of hallucinogenic drugs. I: Antagonist correlation analysis". Psychopharmacology. 121 (3): 347–56. doi:10.1007/bf02246074. PMID 8584617.

- ↑ Seeman P, Watanabe M, Grigoriadis D, et al. (November 1985). "Dopamine D2 receptor binding sites for agonists. A tetrahedral model". Molecular Pharmacology. 28 (5): 391–9. PMID 2932631.

- ↑ Burt DR, Creese I, Snyder SH (April 1977). "Antischizophrenic drugs: chronic treatment elevates dopamine receptor binding in brain". Science. 196 (4287): 326–8. doi:10.1126/science.847477. PMID 847477.

- 1 2 Jagadish Prasad, P. (2010). Conceptual Pharmacology. Universities Press. pp. 295, 303, 598. ISBN 978-81-7371-679-9. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ "RxList: Promethazine Description". 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Ban, TA (2006). "The role of serendipity in drug discovery". Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 8 (3): 335–44. PMC 3181823. PMID 17117615.

- ↑ "Paul Charpentier, Henri-Marie Laborit, Simone Courvoisier, Jean Delay, and Pierre Deniker". Science History Institute. August 6, 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ Liptak, Adam (2001-09-18). "Drug Label, Maimed Patient and Crucial Test for Justices". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Stout, David (2009-03-04). "Drug Approval Is Not a Shield From Lawsuits, Justices Rule". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Intravenous Promethazine and Severe Tissue Injury, Including Gangrene". 2013-08-15.

External links

- "Promethazine". U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health.