Typical antipsychotic

| Typical antipsychotic | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

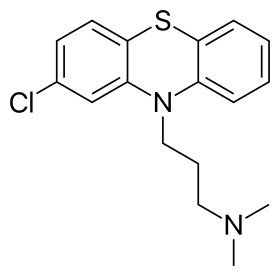

Skeletal formula of chlorpromazine, the first neuroleptic drug | |

| Synonyms | First generation antipsychotics, conventional antipsychotics, classical neuroleptics, traditional antipsychotics, major tranquilizers |

| In Wikidata | |

Typical antipsychotics are a class of antipsychotic drugs first developed in the 1950s and used to treat psychosis (in particular, schizophrenia). Typical antipsychotics may also be used for the treatment of acute mania, agitation, and other conditions. The first typical antipsychotics to come into medical use were the phenothiazines, namely chlorpromazine which was discovered serendipitously.[1] Another prominent grouping of antipsychotics are the butyrophenones, an example of which would be haloperidol. The newer, second-generation antipsychotics, also known as atypical antipsychotics, have replaced the typical antipsychotics due to the Parkinson-like side effects typicals have.

Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's dopamine pathways, but atypicals at the time of marketing were claimed to differ from typical antipsychotics in that they are less likely to cause extrapyramidal motor control disabilities in patients, which include unsteady Parkinson's disease-type movements, body rigidity and involuntary tremors.[2] More recent research has demonstrated the side effect profile of these drugs is similar to older drugs, causing the leading medical journal The Lancet to write in its editorial "the time has come to abandon the terms first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics, as they do not merit this distinction."[3] These abnormal body movements can become permanent even after medication is stopped. While typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause parkinsonism, atypicals are more likely to cause weight gain and type II diabetes.[4]

Adverse effects

Side effects vary among the various agents in this class of medications, but common side effects include: dry mouth, muscle stiffness, muscle cramping, tremors, EPS and weight gain. EPS refers to a cluster of symptoms consisting of akathisia, parkinsonism, and dystonia. Anticholinergics such as benztropine and diphenhydramine are commonly prescribed to treat the EPS. 4% of patients develop the Rabbit syndrome while on typical antipsychotics.[5]

There is a significant risk of the serious condition tardive dyskinesia developing as a side effect of typical antipsychotics. The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia after chronic typical antipsychotic usage varies on several factors, such as age and gender, as well as the specific antipsychotic used. The commonly reported incidence of TD among younger patients is about 5% per year. Among older patients incidence rates as high as 20% per year have been reported. The average prevalence is approximately 30%.[6] There are no treatments that have consistently been shown to be effective for the treatment of tardive dyskinesias, however branched chain amino acids, melatonin, and vitamin E have been suggested as possible treatments. The atypical antipsychotic clozapine has also been suggested as an alternative antipsychotic for patients experiencing tardive dyskinesia. Tardive dyskinesia may reverse upon discontinuation of the offending agent or it may be irreversible, withdrawal may also make tardive dyskinesia more severe.[7]

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, or NMS, is a rare, but potentially fatal side effect of antipsychotic treatment. NMS is characterized by fever, muscle rigidity, autonomic dysfunction, and altered mental status. Treatment includes discontinuation of the offending agent and supportive care.

The role of typical antipsychotics has come into question recently as studies have suggested that typical antipsychotics may increase the risk of death in elderly patients. A retrospective cohort study from the New England Journal of Medicine on Dec. 1, 2005 showed an increase in risk of death with the use of typical antipsychotics that was on par with the increase shown with atypical antipsychotics.[8] This has led some to question the common use of antipsychotics for the treatment of agitation in the elderly, particularly with the availability of alternatives such as mood stabilizing and antiepileptic drugs.

High-potency and low-potency

Traditional antipsychotics are classified as either high-potency or low-potency:

| Potency | Examples | Adverse effect profile |

| high-potency | fluphenazine and haloperidol | more extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) and less antihistaminic (e.g. sedation), alpha adrenergic (e.g. orthostatic hypotension) and anticholinergic effects (e.g. dry mouth) |

| low-potency | chlorpromazine | fewer EPS but more H1, α1, and muscarinic blocking effects |

Depot injections

Some of the high-potency antipsychotics have been formulated as the decanoate ester (e.g. fluphenazine decanoate) to allow for a slow release of the active drug when given as a deep, intramuscular injection. This has the advantage of providing reliable dosing for a person who doesn't want to take the medication. Depot injections can also be used for involuntary community treatment patients to ensure compliance with a community treatment order when the patient would refuse to take daily oral medication. Depot preparations were limited to high-potency antipsychotics so choice was limited.

The oldest depots available were haloperidol and fluphenazine, with flupentixol and zuclopenthixol as more recent additions. All have a similar, predominantly extrapyramidal, side effect profile though there are some variations between patients. More recently, long acting preparations of the atypical antipsychotic, risperidone, and its metabolite paliperidone, have become available thus offering new choices. However, Risperidone tends to have a higher incidence of extrapyramidal effects when compared to the tricyclic and tetracyclic atypical antipsychotics, such as quetiapine, clozapine, olanzapine, etc.

Typical medications

A measure of "chlorpromazine equivalence" is used to compare the relative effectiveness of antipsychotics.[9][10] The measure specifies the amount (mass) in milligrams of a given drug that must be administered in order to achieve desired effects equivalent to those of 100 milligrams of chlorpromazine. Agents with a chlorpromazine equivalence ranging from 5 to 10 milligrams would be considered "medium potency", and agents with 2 milligrams would be considered "high potency".[11][12]

Prochlorperazine (Compazine, Buccastem, Stemetil) and Pimozide (Orap) are less commonly used to treat psychotic states, and so are sometimes excluded from this classification.[13]

Low potency

- Chlorpromazine

- Chlorprothixene

- Levomepromazine

- Mesoridazine

- Periciazine

- Promazine

- Thioridazine† (withdrawn by brand-name manufacturer and most countries)

Medium potency

High potency

- Droperidol

- Flupentixol

- Fluphenazine

- Haloperidol

- Pimozide

- Prochlorperazine

- Thioproperazine

- Trifluoperazine

- Zuclopenthixol

Where: † indicates products that have since been discontinued.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Shen, W. W. (1999). "A history of antipsychotic drug development". Comprehensive psychiatry. 40 (6): 407–14. PMID 10579370.

- ↑ "A Roadmap to Key Pharmacologic Principles in Using Antipsychotics". The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (6): 444–54. 2007. doi:10.4088/PCC.v09n0607. PMC 2139919. PMID 18185824.

- ↑ Tyrer, Peter; Kendall, Tim (2009). "The spurious advance of antipsychotic drug therapy". The Lancet. 373 (9657): 4–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61765-1. PMID 19058841.

- ↑ "Not found". www.rcpsych.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ↑ Yassa, R; Lal, S (1986). "Prevalence of the rabbit syndrome". American Journal of Psychiatry. 143 (5): 656–7. doi:10.1176/ajp.143.5.656. PMID 2870650.

- ↑ Llorca, Pierre-Michel; Chereau, Isabelle; Bayle, Frank-Jean; Lancon, Christophe (2002). "Tardive dyskinesias and antipsychotics: A review". European Psychiatry. 17 (3): 129–38. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(02)00647-8. PMID 12052573.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- ↑ Wang, Philip S.; Schneeweiss, Sebastian; Avorn, Jerry; Fischer, Michael A.; Mogun, Helen; Solomon, Daniel H.; Brookhart, M. Alan (2005). "Risk of Death in Elderly Users of Conventional vs. Atypical Antipsychotic Medications". New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (22): 2335–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052827. PMID 16319382.

- ↑ Woods, Scott W. (2003). "Chlorpromazine Equivalent Doses for the Newer Atypical Antipsychotics". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (6): 663–7. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0607. PMID 12823080.

- ↑ Rijcken, Claudia A.W.; Monster, Taco B.M.; Brouwers, Jacobus R.B.J.; De Jong-Van Den Berg, Lolkje T.W. (2003). "Chlorpromazine Equivalents Versus Defined Daily Doses: How to Compare Antipsychotic Drug Doses?". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 23 (6): 657–9. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000096247.29231.3a. PMID 14624195.

- ↑ Diana Perkins; Jeffrey A. Liberman; Lieberman, Jeffrey A. (2006). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Schizophrenia. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 305. ISBN 1-58562-191-9.

- ↑ Venkatasubramanian, Ganesan; Danivas, Vijay (2013). "Current perspectives on chlorpromazine equivalents: Comparing apples and oranges!". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 55 (2): 207–8. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.111475. PMC 3696254. PMID 23825865.

- ↑ Gitlin, Michael J. (1996). The psychotherapist's guide to psychopharmacology. New York: Free Press. p. 392. ISBN 0-684-82737-9.

- ↑ Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.