Baclofen

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lioresal, Liofen, Gablofen, others |

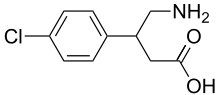

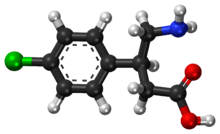

| Synonyms | β-(4-chlorophenyl)-γ-aminobutyric acid (β-(4-chlorophenyl)-GABA) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intrathecal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Well-absorbed |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | 85% excreted in urine/faeces unchanged. 15% metabolised by deamination |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5 to 4 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (70–80%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.013.170 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H12ClNO2 |

| Molar mass | 213.661 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Baclofen, sold under the brand name Lioresal among others, is a medication used to treat spasticity. It is used as a central nervous system depressant and skeletal muscle relaxant. It is also used in topical creams to help with pain.[1]

Chemically it is a derivative of the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). It is believed to work by activating (or agonizing) GABA receptors, specifically the GABAB receptors.[2] Its beneficial effects in spasticity result from its actions in the brain and spinal cord.[3]

As of 2015 the cost for a typical course of treatment in the United States is less than 25 USD.[4]

Medical uses

Spasticity

Baclofen is primarily used for the treatment of spastic movement disorders, especially in instances of spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy, and multiple sclerosis.[5] Its use in people with stroke or Parkinson's disease is not recommended.[5]

Alcoholism

Baclofen is being studied for the treatment of alcoholism.[6] While evidence is promising that it may help with alcohol withdrawal syndrome, as of 2017 it is not strong enough to recommend its use for this purpose.[6][7]

In 2014, the French drug agency ANSM issued a 3-year temporary recommendation allowing the use of baclofen in alcoholism.[8]

Others

It is being studied along with naltrexone and sorbitol for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT), a hereditary disease that causes peripheral neuropathy.[9] It is also being studied for cocaine addiction.[10] Baclofen and other muscle relaxants are being studied for potential use for persistent hiccups.[11][12]

Side effects

Briefly, adverse effects may include drowsiness, dizziness, weakness, fatigue, headache, trouble sleeping, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or constipation. A complete list of reported adverse effects can be found on the product insert.[13]

Withdrawal syndrome

Discontinuation of baclofen can be associated with a withdrawal syndrome which resembles benzodiazepine withdrawal and alcohol withdrawal. Withdrawal symptoms are more likely if baclofen is used for long periods of time (more than a couple of months) and can occur from low or high doses. The severity of baclofen withdrawal depends on the rate at which it is discontinued. Thus to minimise withdrawal symptoms, the dose should be tapered down slowly when discontinuing baclofen therapy. Abrupt withdrawal is more likely to result in severe withdrawal symptoms. Acute withdrawal symptoms can be stopped by recommencing baclofen.[14]

Withdrawal symptoms may include auditory hallucinations, visual hallucinations, tactile hallucinations, delusions, confusion, agitation, delirium, disorientation, fluctuation of consciousness, insomnia, dizziness (feeling faint), nausea, inattention, memory impairments, perceptual disturbances, pruritus/itching, anxiety, depersonalization, hypertonia, hyperthermia, formal thought disorder, psychosis, mania, mood disturbances, restlessness, and behavioral disturbances, tachycardia, seizures, tremors, autonomic dysfunction, hyperpyrexia (fever), extreme muscle rigidity resembling neuroleptic malignant syndrome and rebound spasticity.[14][15]

Abuse potential

Baclofen, at standard dosing, does not produce euphoria or other pleasant effects, does not possess addictive properties, and has not been associated with any degree of drug craving.[6][16] There are very few cases of abuse of baclofen for reasons other than attempted suicide.[6] In contrast to baclofen, another GABAB receptor agonist, γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), has been associated with euphoria, abuse, and addiction.[17] These effects are likely mediated not by activation of the GABAB receptor, but rather by activation of the GHB receptor.[17] Although baclofen does not produce euphoria or other reinforcing effects, which is unlike alcohol and benzodiazepines (as well as GHB), it does similarly possess sedative and antianxiety properties.[16]

Overdose

Reports of overdose indicate that baclofen may cause symptoms including vomiting, weakness, sedation, somnolence, respiratory depression, seizures, unusual pupil size, dizziness,[18] headaches,[18] itching, hypothermia, bradycardia, hypertension, hyporeflexia, coma, and death.[19]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Baclofen produces its effects by activating the GABAB receptor, similar to the drug phenibut which also activates this receptor and shares some of its effects. Baclofen is postulated to block mono-and-polysynaptic reflexes by acting as an inhibitory neurotransmitter, blocking the release of excitatory transmitters. However, baclofen does not have significant affinity for the GHB receptor, and has no known abuse potential.[20] The modulation of the GABAB receptor is what produces baclofen's range of therapeutic properties.

Similarly to phenibut (β-phenyl-GABA), as well as pregabalin (β-isobutyl-GABA), which are close analogues of baclofen, baclofen (β-(4-chlorophenyl)-GABA) has been found to block α2δ subunit-containing voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs).[21] However, it is weaker relative to phenibut in this action (Ki = 23 and 39 μM for R- and S-phenibut and 156 μM for baclofen).[21] Moreover, baclofen is in the range of 100-fold more potent by weight as an agonist of the GABAB receptor in comparison to phenibut, and in accordance, is used at far lower relative dosages. As such, the actions of baclofen on α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs are likely not clinically-relevant.[21]

Pharmacokinetics

The drug is rapidly absorbed after oral administration and is widely distributed throughout the body. Biotransformation is low and the drug is predominantly excreted unchanged by the kidneys.[22] The half life of baclofen is roughly 2–4 hours and it therefore needs to be administered frequently throughout the day to control spasticity appropriately.

Chemistry

Baclofen is a white (or off-white) mostly odorless crystalline powder, with a molecular weight of 213.66 g/mol. It is slightly soluble in water, very slightly soluble in methanol, and insoluble in chloroform.

History

Historically, baclofen was designed as a drug for treating epilepsy. It was first made at Ciba-Geigy, by the Swiss chemist Heinrich Keberle, in 1962.[23][24] Its effect on epilepsy was disappointing, but it was found that in certain people, spasticity decreased.

Currently, baclofen continues to be given by mouth, with variable effects. In severely affected children, the oral dose is so high that side-effects appear, and the treatment loses its benefit. How and when baclofen came to be used in the spinal sac (intrathecally) remains unclear, but as of 2012, this has become an established method of treating spasticity in many conditions.

In his 2008 book, Le Dernier Verre (translated literally as The Last Glass or The End of my Addiction), French-American cardiologist Olivier Ameisen described how he treated his alcoholism with baclofen. Inspired by this book, an anonymous donor gave $750,000 to the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands to initiate a clinical trial of high-dose baclofen, which Ameisen had called for since 2004.[25]

Society and culture

Routes of administration

Baclofen can be administered transdermally as part of a pain-relieving and muscle-relaxing topical cream mix at a compounding pharmacy, orally[26] or intrathecally[27] (directly into the cerebral spinal fluid) using a pump implanted under the skin.

Intrathecal pumps offer much lower doses of baclofen because they are designed to deliver the medication directly to the spinal fluid rather than going through the digestive and blood system first. They are often preferred in spasticity patients such as those with spastic diplegia, as very little of the oral dose actually reaches the spinal fluid. Besides those with spasticity, intrathecal administration is also used in patients with multiple sclerosis who have severe painful spasms which are not controllable by oral baclofen. With pump administration, a test dose is first injected into the spinal fluid to assess the effect, and if successful in relieving spasticity, a chronic intrathecal catheter is inserted from the spine through the abdomen and attached to the pump which is implanted under the abdomen's skin, usually by the ribcage. The pump is computer-controlled for automatic dosage and the reservoir in the pump can be replenished by percutaneous injection. The pump also has to be replaced about every 5 years due to the battery life and other wear.

Other names

Synonyms include chlorophenibut. Brand names include Beklo, Baclodol, Flexibac, Gablofen, Kemstro, Liofen, Lioresal, Lyflex, Clofen, Muslofen, Bacloren, Baklofen, Sclerofen, and others.

References

- ↑ Cherny, Nathan; Fallon, Marie; Kaasa, Stein; Portenoy, Russell K.; Currow, David C. (2015). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 585. ISBN 9780191509483.

- ↑ "Product Information Clofen". TGA eBusiness Services. Millers Point, Australia: Alphapharm Pty Limited. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Brayfield, A, ed. (9 January 2017). "Baclofen: Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference". MedicinesComplete. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 1. ISBN 9781284057560.

- 1 2 "Baclofen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Leggio, L.; Garbutt, J. C.; Addolorato, G. (Mar 2010). "Effectiveness and safety of baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependent patients". CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 9 (1): 33–44. doi:10.2174/187152710790966614. PMID 20201813.

- ↑ Liu, J.; Wang, L. N. (20 August 2017). "Baclofen for alcohol withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD008502. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008502.pub5. PMID 28822350.

- ↑ "Une recommandation temporaire d’utilisation (RTU) est accordée pour le baclofène – Point d'information", ANSM, 14 March 2014.

- ↑ Attarian, Shahram; Vallat, Jean-Michel; Magy, Laurent; Funalot, Benoît; Gonnaud, Pierre-Marie; Lacour, Arnaud; Péréon, Yann; Dubourg, Odile; Pouget, Jean; Micallef, Joëlle; Franques, Jérôme; Lefebvre, Marie-Noëlle; Ghorab, Karima; Al-Moussawi, Mahmoud; Tiffreau, Vincent; Preudhomme, Marguerite; Magot, Armelle; Leclair-Visonneau, Laurène; Stojkovic, Tanya; Bossi, Laura; Lehert, Philippe; Gilbert, Walter; Bertrand, Viviane; Mandel, Jonas; Milet, Aude; Hajj, Rodolphe; Boudiaf, Lamia; Scart-Grès, Catherine; Nabirotchkin, Serguei; Guedj, Mickael; Chumakov, Ilya; Cohen, Daniel (2014). "An exploratory randomised double-blind and placebo-controlled phase 2 study of a combination of baclofen, naltrexone and sorbitol (PXT3003) in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 9 (1): 199. doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0199-0.

- ↑ Kampman, KM (2005). "New medications for the treatment of cocaine dependence". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2 (12): 44–48. PMC 2994240. PMID 21120115.

- ↑ "What Is the Latest on Treatment for Hiccups?". Medscape. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ↑ Walker, Paul; Watanabe, Sharon; Bruera, Eduardo (1998). "Baclofen, A Treatment for Chronic Hiccup". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 16 (2): 125–132. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00039-6.

- ↑ https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022462s000lbl.pdf

- 1 2 Leo, R. J.; Baer, D. (Nov–Dec 2005). "Delirium Associated With Baclofen Withdrawal: A Review of Common Presentations and Management Strategies". Psychosomatics. 46 (6): 503–07. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.6.503. PMID 16288128. Archived from the original on 2006-02-09.

- ↑ Grenier, B.; Mesli, A.; Cales, J.; Castel, J. P.; Maurette, P. (1996). "[Severe hyperthermia caused by sudden withdrawal of continuous intrathecal administration of baclofen]". Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 15 (5): 659–62. doi:10.1016/0750-7658(96)82130-7. PMID 9033759.

- 1 2 Agabio, Roberta; Preti, Antonio; Gessa, Gian Luigi (2013). "Efficacy and Tolerability of Baclofen in Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review". European Addiction Research. 19 (6): 325–45. doi:10.1159/000347055. ISSN 1421-9891. PMID 23775042.

- 1 2 van Nieuwenhuijzen, P.S.; McGregor, I.S.; Hunt, G.E. (2009). "The distribution of γ-hydroxybutyrate-induced Fos expression in rat brain: Comparison with baclofen". Neuroscience. 158 (2): 441–55. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.011. ISSN 0306-4522. PMID 18996447.

- 1 2 "Gablofen (Baclofen) FDA Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ "Baclofen Overdose: Drug Experimentation in a Group of Adolescents". Pediatrics. 101 (6): 1045–48. 1998. doi:10.1542/peds.101.6.1045. ISSN 0031-4005.

- ↑ Carter, L. P.; Koek, W.; France, C. P. (October 2008). "Behavioral analyses of GHB: Receptor mechanisms". Pharmacol. Ther. 121 (1): 100–14. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.003. PMC 2631377. PMID 19010351.

- 1 2 3 Zvejniece L, Vavers E, Svalbe B, Veinberg G, Rizhanova K, Liepins V, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M (2015). "R-phenibut binds to the α2-δ subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels and exerts gabapentin-like anti-nociceptive effects". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 137: 23–29. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2015.07.014. PMID 26234470.

- ↑ Wuis, E. W.; Dirks, M. J. M.; Termond, E. F. S.; Vree, T. B.; Kleijn, E. (1989). "Plasma and urinary excretion kinetics of oral baclofen in healthy subjects". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 37 (2): 181–84. doi:10.1007/BF00558228. PMID 2792173.

- ↑ Froestl, Wolfgang (2010). "Chemistry and Pharmacology of GABAb Receptor Ligands". In Blackburn, Thomas P. GABAb Receptor Pharmacology – A Tribute to Norman Bowery. Advances in Pharmacology. 58. pp. 19–62. doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(10)58002-5. ISBN 978-0-12-378647-0.

- ↑ Yogeeswari, P.; Ragavendran, J. V.; Sriram, D. (2006). "An update on GABA analogs for CNS drug discovery" (PDF). Recent patents on CNS drug discovery. 1 (1): 113–18. doi:10.2174/157488906775245291. PMID 18221197. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-16.

- ↑ Enserink, M. (2011). "Anonymous Alcoholic Bankrolls Trial of Controversial Therapy". Science. 332 (6030): 653. doi:10.1126/science.332.6030.653. PMID 21551041. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ CID 3738, Tablet

- ↑ CID 2284

External links