COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic spread to the United Kingdom in late January 2020. As of 21 June 2020 there have been 304,331 confirmed cases[nb 4] and 42,632 deaths of confirmed cases,[nb 2] the world's second-highest death rate per capita among major countries.[3][4] There were 53,664 deaths where the death certificate mentioned COVID-19 by 12 June (see Statistics).[5] More than 90% of those dying had underlying illnesses or were over 60 years old. The infection rate is higher in care homes than in the community. There is large regional variation in the outbreak's severity. In March, London had the highest number of infections[6] while North East England has the highest infection rate.[7] England is the country of the UK with the highest recorded death rate per capita, while Northern Ireland has the lowest. Healthcare in the UK is devolved to each country.

| COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

Confirmed cases per 100,000 residents[nb 1]

| |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | United Kingdom |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, China |

| Index case | York |

| Arrival date | 31 January 2020 (4 months, 3 weeks and 6 days ago)[1] |

| Confirmed cases | 304,331 [2] |

Deaths | 42,632 [nb 2][2] |

| Government website | |

| UK Government information and advice[nb 3] Scottish Government information and advice Welsh Government information and advice | |

The Department of Health and Social Care launched a public health information campaign to help slow the virus's spread, and began posting daily updates in early February. In February, the Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, introduced the Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020 for England, and hospitals set up drive-through screening. The Chief Medical Officer for England, Chris Whitty, outlined a four-pronged strategy to tackle the outbreak: contain, delay, research and mitigate.

In March, the UK government imposed a lockdown, banning all "non-essential" travel and contact with people outside one's home (including family and partners), and shutting almost all schools, business, venues, facilities, amenities and places of worship. Those with symptoms, and their household, were told to self-isolate, while the most vulnerable (the over 70s and those with certain illnesses) were told to shield themselves. People were made to keep apart in public. Police were empowered to enforce the lockdown, and the Coronavirus Act 2020 gave the government emergency powers[8] not used since the Second World War.[9][10] Panic buying was reported.

It was forecast that a lengthy lockdown would severely damage the UK economy,[11] lead to millions of job losses,[12] worsen mental health and suicide rates,[13] and cause "collateral" deaths due to isolation, delays and falling living standards. Researchers suggested the lockdown could be lifted by shielding the most vulnerable and using contact tracing.

All four national health services (NHS Wales, Northern Ireland, England and Scotland) worked to raise hospital capacity and set up temporary critical care hospitals. By mid-April NHS Providers, the membership organisation for NHS trusts in England, predicted it could now cope with a peak in cases,[14] and it was reported that social distancing had "flattened the curve" of the epidemic.[15] In late April, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that the UK had passed the peak of its outbreak.[16]

Background

On 12 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that a novel coronavirus was the cause of a respiratory illness in a cluster of people in Wuhan City, Hubei, China, which was reported to the WHO on 31 December 2019.[17][18] The case fatality ratio for COVID-19 has been much lower than SARS of 2003,[19][20] but the transmission has been significantly greater, with a significant total death toll.[21][19]

Mathematical modelling

Reports from the Medical Research Council's Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College, London have been providing mathematically calculated estimates of cases and case fatality rates.[22][23] In February, the team at Imperial, led by epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, estimated about two-thirds of cases in travellers from China were not detected and that some of these may have begun "chains of transmission within the countries they entered".[24][25][26] They forecast that the new coronavirus could infect up to 60% of the UK's population, in the worst-case scenario.[27]

In a paper on 16 March, the Imperial team provided detailed forecasts of the potential impacts of the epidemic in the UK and US.[28][29] It detailed the potential outcomes of an array of 'non-pharmaceutical interventions'. Two potential overall strategies outlined were: mitigation, in which the aim is to reduce the health impact of the epidemic but not to stop transmission completely; and suppression, where the aim is to reduce transmission rates to a point where case numbers fall. Until this point, government actions had been based on a strategy of mitigation, but the modelling predicted that while this would reduce deaths by approximately 2/3, it would still lead to approximately 250,000 deaths from the disease and the health systems becoming overwhelmed.[28] On 16 March, the Prime Minister announced changes to government advice, extending self-isolation to whole households, advising social distancing particularly for vulnerable groups, and indicating that further measures were likely to be required in the future.[30][29] A paper on 30 March by Imperial estimated that the lockdown would reduce the number of dead from 510,000 to less than 20,000.[31]

In April, biostatistician Professor Sheila Bird said delay in the reporting of deaths from the virus meant there was a risk of underestimating the steepness of the rising epidemic trend.[32]

Timeline

Late 2019: suspected cases

In May 2020, the BBC reported that several members of a choir in Yorkshire had suffered COVID-19-like symptoms shortly after the partner of one of the choir members returned from a business trip to Wuhan, China, on 17 or 18 December.[36]

January 2020: first confirmed cases

On 22 January, following a confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States the previous day, in a man returning to Washington from Wuhan, China, where there were 440 confirmed cases at the time, the DHSC and PHE raised the risk level from "very low" to "low". As a result, Heathrow Airport received additional clinical support and tightened surveillance of the three direct flights from Wuhan every week; each was to be met by a Port Health team with Mandarin and Cantonese language support. In addition, all airports in the UK were to make written guidance available for unwell travellers.[37][38] Simultaneously, efforts to trace 2,000 people who had flown into the UK from Wuhan over the previous 14 days were made.[39][40]

On 31 January, the first UK cases were confirmed in York.[41][42] On the same day, British nationals were evacuated from Wuhan to quarantine at Arrowe Park Hospital.[43] However, due to confusion over eligibility, some people missed the flight.[43]

February 2020: early spread

On 6 February, a third confirmed case was reported in Brighton - a man who returned from Singapore and France to the UK on 28 January.[44][45][46] Following confirmation of his result, the UK's CMOs expanded the number of countries where a history of previous travel associated with flu-like symptoms—such as fever, cough, and difficulty breathing—in the previous 14 days would require self-isolation and calling NHS 111. These countries included China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Malaysia, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand.[47]

On 23 February, the DHSC confirmed four new cases from the Diamond Princess cruise ship.[48]

On 26/27 February, a Nike conference in Edinburgh led to at least 25 cases including 8 residents of Scotland. Health Protection Scotland established an incident management team at the time and traced contacts from delegates.[49] On 27 and 28 February, first cases were confirmed in Wales and Northern Ireland.[50][51]

March 2020: closures and restrictions

Early to mid-March: closures and cancellations

On 1 March, a further 13 cases were reported including new cases in Greater Manchester and Scotland; bringing the total to 36, three of which were believed to be contacts of the case in Surrey who had no history of travel abroad.[52][53]

On 3 March the UK Government unveiled their Coronavirus Action Plan, which outlined what the UK had done and what it planned to do next.[54] Paul Cosford, a medical director at Public Health England, said widespread transmission of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom was "highly likely".[55]

On 5 March, the first death from COVID-19, a woman in her 70s, was reported in Reading,[56] and the second, a man in his 80s in Milton Keynes, was reported to have died later that day.[57][58]

On 12 March, the total of cases in the UK was reported to be 590.[54] On the same day, the UK CMOs raised the risk to the UK from moderate to high.[59] The government advised that anyone with a new continuous cough or a fever should self-isolate for seven days. Schools were asked to cancel trips abroad, and people over 70 and those with pre-existing medical conditions were advised to avoid cruises.[60][61]

The 2020 United Kingdom local elections were postponed for a year.[62]

On 16 March, Prime Minister Boris Johnson advised everyone in the UK against "non-essential" travel and contact with others, as well as suggesting people should avoid pubs, clubs and theatres, and work from home if possible. Pregnant women, people over 70 and those with certain health conditions were urged to consider the advice "particularly important", and would be asked to self-isolate within days.[30] On the same day, a second MP, Kate Osborne, tested positive after a period of self-isolation.[63][64][65][66]

On 17 March, NHS England announced that all non-urgent operations in England would be postponed from 15 April to free up 30,000 beds.[67] General practice moved rapidly to remote working. In March 2020 the proportion of telephone appointments increased by over 600%.[68]

On 17 March, the government provided a £3.2million emergency support package to help rough sleepers into accommodation.[69][70] With complex physical and mental health needs, in general, homeless people are at a significant risk of catching the virus.[69]

Late March: restrictions begin

Having previously "advised" the public to avoid pubs and restaurants, on 23 March, Boris Johnson announced in a television broadcast that measures to mitigate the virus were to be tightened further to protect the NHS, with wide-ranging restrictions made on freedom of movement, enforceable in law,[8] for a "stay at home" period which would last for at least three weeks.[71] The government directed people to stay at home throughout this period except for essential purchases, essential work travel (if remote work was not possible), medical needs, one exercise per day (alone or with household members), and providing care for others.[72] Many other non-essential activities, including all public gatherings and social events except funerals, were prohibited, with many categories of retail businesses ordered to be closed.[8][73] Despite the announcement, the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020, which made the sweeping restrictions legally enforceable, did not take effect until three days later on 26 March.[74]

The UK, Scottish and Welsh Parliaments scaled back their activities.[75]

On 26 March, the number of UK coronavirus deaths increased by more than 100 in a day for the first time, rising to 578, while a total of 11,568 had tested positive for the virus.[76] At 8:00 pm that day, people from across the UK took part in national applause in appreciation of health workers.[77] This applause was repeated the following week.[78]

On 27 March, Boris Johnson and Matt Hancock announced that they had tested positive for the virus.[79][80] On the same day, Labour Party MP Angela Rayner, the Shadow Secretary of State for Education, confirmed she had been suffering symptoms and was self-isolating.[81] Chief Medical Adviser Chris Whitty also reported suffering from symptoms and would be self-isolating, while continuing to advise the UK government.[82] That day also saw the largest increase in the number of deaths, with the figure rising by 181 from the previous day, bringing the total to 759, while 14,579 cases had been confirmed.[83]

On 29 March, it was reported that the government would send a letter to 30 million households warning things would "get worse before they get better" and that tighter restrictions could be implemented if necessary. The letter would also be accompanied by a leaflet setting out the government's lockdown rules along with health information.[84] Dr Jenny Harries, England's deputy chief medical officer, suggested it could be six months before life could return to "normal", because social distancing measures would have to be reduced "gradually".[85] The first NHS nurse died of COVID-19.[86]

On 30 March the Prime Minister's senior adviser Dominic Cummings was reported to be self-isolating after experiencing coronavirus symptoms. He had been at Downing Street on 27 March and was stated to have developed symptoms over 28 and 29 March[87]

At the end of March, transmission within the community was thought to be decreasing, and hospital admission data suggested cases were increasing at a slower rate.[88] The Foreign and Commonwealth Office repatriated tens of thousands of British nationals who had been stranded abroad by the coronavirus outbreak.[89]

April 2020

On 1 April, the government confirmed that a total of 2,000 NHS staff had been tested for coronavirus since the outbreak began, but Cabinet Office Minister Michael Gove said a shortage of chemical reagents needed for COVID-19 testing meant it was not possible to screen the NHS's 1.2 million workforces.[90] Gove's statement was contradicted by the Chemical Industries Association, which said there was not a shortage of the relevant chemicals and that at a meeting with a business minister the week before the government had not tried to find out about potential supply problems.[91] On 1 April the number of deaths was confirmed to have increased by 563 to 2,362, while a total of 29,474 cases had been diagnosed, 4,324 over the previous 24 hours.[90]

On 2 April, Health Secretary Matt Hancock, after his seven-day period of isolation, announced a "five pillar" plan for testing people for the virus, with the aim of conducting 100,000 tests a day by the end of April.[92] At 8:00 pm on 2 April the UK gave another national round of applause for NHS staff and other key workers.[93]

With the warm weather forecast for some areas during the upcoming weekend, on 3 April Hancock warned people to stay at home, telling them this was an instruction "not a request".[94] On 4 April it was announced that a five-year-old had died from the virus, believed to be the youngest victim to date.[95] The death total was reported as 4,313, having risen by 708 from the previous day's figure.

That day, Boris Johnson was admitted to hospital as a "precautionary measure" after suffering from symptoms for more than a week with no improvement.[96] Catherine Calderwood, the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland, resigned from her post after it emerged she had been spoken to by police for visiting her second home during lockdown.[97] On 6 April, Johnson was moved to the intensive care unit at St Thomas' Hospital in London as his symptoms worsened. First Secretary of State Dominic Raab assumed Johnson's duties.[98]

On 7 April the number of reported deaths increased by 786, taking the total to 6,159. The figure compared with 439 deaths for the previous day. Patrick Vallance, the government's chief scientific adviser, said the figures were not accelerating as had been predicted but it was too early to tell whether the outbreak was peaking.[99][100]

On 8 April, Mark Drakeford, the First Minister of Wales, confirmed the Welsh Government would extend the lockdown beyond the initial three-week period for Wales.[101] On that day a further 938 deaths were reported in the UK, taking the total to 7,097.[102]

On 9 April the number of daily recorded deaths increased by 881, taking the total to 7,978. Dominic Raab said the UK was "starting to see the impact" of the restrictions but it was "too early" to lift them, and urged people to stay indoors over the Easter weekend.[103] With warm weather forecast again for Easter, this message was echoed by police and tourist destinations.[104] Johnson was moved out of intensive care, but remained in hospital.[105] At 8:00 pm on 9 April the nation staged a third round of applause for NHS staff and other key workers.[106]

On 10 April the UK recorded another 980 deaths taking the total to 8,958. Jonathan Van-Tam, England's deputy chief medical officer, told the UK Government's daily briefing the lockdown was "beginning to pay off" but the UK was still in a "dangerous situation", and although cases in London had started to drop they were still rising in Yorkshire and the North East.[107] Matt Hancock told the briefing a "Herculean effort" was being made to ensure daily deliveries of personal protective equipment (PPE) to frontline workers, including the establishment of domestic manufacturing industry to produce the equipment. Fifteen drive-through testing centres had also been opened around the UK to test frontline workers.[108]

On 11 April the number of reported deaths increased by 917, taking the total to 9,875. After some NHS workers said they still did not have the correct personal protective equipment to treat patients, Home Secretary Priti Patel told that day's Downing Street briefing she was "sorry if people feel there have been failings" in providing kit.[109]

Boris Johnson left hospital on Sunday 12 April.[110] On that day a further 737 coronavirus-related deaths were reported, taking the total past 10,000 to 10,612. Matt Hancock described it as a "sombre day".[111] On 13 April the number of reported deaths increased by 717 to 11,329. Dominic Raab told the Downing Street briefing the government did not expect to make any immediate changes to the lockdown restrictions and that the UK's plan "is working [but] we are still not past the peak of this virus".[112]

On 14 April the number of reported deaths increased by 778 to 12,107.[113] On that day figures released by the Office of National Statistics indicated that coronavirus had been linked to one in five deaths during the week ending 3 April. More than 16,000 deaths in the UK were recorded for that week, 6,000 higher than would be the average for that time of year.[114] Several UK charities, including Age UK and the Alzheimer's Society, expressed their concern that older people were being "airbrushed" out of official figures because they focus on hospital deaths while not including those in care homes or a person's own home. Responding to these concerns, Therese Coffey, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, said hospital figures were being used because "it's accurate and quick".[115]

Matt Hancock announced new guidelines that would allow close family members to see dying relatives to say goodbye to them. Hancock also launched a new network to provide personal protective equipment to care home staff.[116] On that day, NHS England and the Care Quality Commission began rolling out tests for care home staff and residents as it was reported the number of care home deaths was rising but that official figures, which rely on death certificates, were not reflecting the full extent of the problem. Helen Whately, the Minister for Social Care, said the government were aware the figures were being understated.[117] Also on 15 April, Arlene Foster, the First Minister of Northern Ireland, extended the period of lockdown in Northern Ireland to 9 May.[118]

On 16 April Dominic Raab briefed that lockdown restrictions would continue for "at least" another three weeks, and to relax them too early would "risk wasting all the sacrifices and all the progress that has been made". He set out five conditions for any easing of the lockdown .[119] On that day the number of recorded deaths increased by 861 to 13,729, while the number of cases of the virus passed 100,000, reaching 103,093.[120] Also on 16 April, the NHS Nightingale Hospital Birmingham was officially opened by Prince William,[121] and the nation staged a fourth round of applause for NHS staff and key workers at 8 pm.[122]

On 17 April the number of recorded deaths rose by 847 taking the total to 14,576. Matt Hancock confirmed coronavirus tests would be rolled out to cover more public service staff such as police officers, firefighters and prison staff.[123]

On 18 April, Imran Ahmad-Khan, the MP for Wakefield, secured a shipment of 110,000 reusable face masks through his connections with charity Solidarités international and the Vietnamese Government for Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust to help tackle the shortage of PPE.[124] Unions representing doctors and nurses expressed concern at a change in government guidelines advising medics to reuse gowns or wear other kits if stocks run low.[125] Speaking at the Downing Street daily briefing later that day, Robert Jenrick, the Secretary of State for Local Government said a further 400,000 gowns would be arriving from Turkey the following day.[126] The number of recorded deaths rose by 888 to 15,464.[127] Care England, the UK's largest care homes representative body, estimated that as many as 7,500 care home residents may have died because of coronavirus, compared to the official figure of 1,400 released a few days earlier.[125] Jenrick announced a further £1.6bn of support for local authorities, on top of £1.6bn that was given to them at the beginning of the outbreak.[128] Jenrick also said parks and cemeteries must remain open.[128]

On 19 April the number of recorded deaths increased by 596 to 16,060. Dr. Jenny Harries said the lower number of deaths was "very good news" but cautioned against drawing conclusions from the figures. The Department for Education announced a focus on home learning for children.[129] Also on 19 April, the flight from Turkey carrying a shipment of 84 tonnes of PPE scheduled to land in the UK that day was delayed.[130]

On 28 April Kawasaki Syndrome was reported in children.[131][132]

On 29 April, the number of people who have died with coronavirus in the UK passed 26,000, as official figures include deaths in the community, such as in care homes, for the first time.[133] On 30 April, Boris Johnson said the country was "past the peak of this disease".[134]

May 2020

_003.jpg)

On 5 May, the UK death toll became the highest in Europe and second highest in the world.[135]

On 7 May, the lockdown in Wales was extended by the Welsh Government, with some slight relaxations.[136][137]

On 10 May, Prime Minister Johnson asked those who could not work from home to go to work, avoiding public transport if possible; and encouraged the taking of "unlimited amounts" of outdoor exercise, and allowing driving to outdoor destinations within England. In his statement he changed the 'Stay at Home' slogan to 'Stay Alert'.[138] The devolved administrations in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales did not adopt the new slogan as there had been no agreement with the UK government to change it, and because the announcement sent a mixed message to the public.[139]

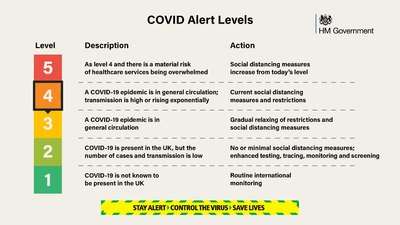

On 11 May, Johnson published a 60-page document called "Our Plan to rebuild: the UK Government's COVID-19 recovery strategy", with details of the COVID-19 recovery strategy for the UK. In the report a new COVID-19 alert level system was announced.[140] At the same time the Cabinet Office published guidance on "staying safe outside your home", comprising eleven principles which "all of us" should adopt "wherever possible".[141]

In May a COVID-19 alert system was announced, to be run by a new joint biosecurity centre. When first announced, Johnson stated that the UK was on level 4, moving towards level 3.[142][140][143]

The Health and Safety Executive stated that from 9 March to 7 May they were contacted 4,813 times. Around 8% of the complaints related to Scotland. The executive managed to resolve 60% of them while another 40% needed further investigation, with some workplaces suspended whilst safety measures were put in place. As of 17 May the executive had not issued any enforcement notices in relation to COVID-19.[144]

On 25 May the prime minister's adviser Dominic Cummings was criticised over his alleged breaches of the lockdown rules.[145][146] Cummings rejected the allegations, denying that he had acted illegally.[147] On 28 May 2020, Durham police said that no offence had been committed when Cummings had travelled from London to Durham and that a minor breach might have occurred at Barnard Castle, but as there had been no apparent breach of social distancing rules, no further action would be taken.[148]

On 28 May Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced an easing of the lockdown in Scotland from the following day, with people able to meet friends and family outside in groups of no more than eight but keeping two metres apart.[149]

June 2020

On 6 June, Parliament Square in London was packed with thousands of people for the Black Lives Matter protest against racism and police violence in the UK. On 7 June, UK Health Minister Matt Hancock stated that although he supports the argument of the protests, there is "undoubtedly" a risk of a potential rise in the number of COVID-19 cases and the spread of the virus.[150]

Government response

Overview

The first published government statement on the coronavirus situation in Wuhan was released on 22 January by the Department of Health and Social Care and Public Health England.[152] Guidance has progressed in line with the number of cases detected and changes in where affected people have contracted the virus, as well as with what has been happening in other countries.[45] In February, Chief Medical Officer (CMO) to the UK Government, Chris Whitty said "we basically have a strategy which depends upon four tactical aims: the first one is to contain; the second of these is to delay; the third of these is to do the science and the research; and the fourth is to mitigate so we can brace the NHS."[153] These aims equate to four phases; specific actions involved in each of these phases are:

- Contain: detect early cases, follow up close contacts, and prevent the disease from taking hold in this country for as long as is reasonably possible

- Delay: slow the spread within the UK, and (if it does take hold) lower the peak impact and push it away from the winter season

- Research: better understand the virus and the actions that will lessen its effect on the UK population; innovate responses including diagnostics, drugs, and vaccines; use the evidence to inform the development of the most effective models of care

- Mitigate: provide the best care possible for people who become ill, support hospitals to maintain essential services and ensure ongoing support for people ill in the community, to minimise the overall impact of the disease on society, public services and on the economy.[154]

The four UK CMOs raised the UK risk level from low to moderate on 30 January 2020, upon the WHO's announcement of the disease as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[54][155] As soon as cases appeared in the UK on 31 January 2020, a public health information campaign, similar to the previous "Catch it, Bin it, Kill it" campaign, was launched in the UK, to advise people how to lessen the risk of spreading the virus.[155] Travellers from Hubei province in China, including the capital Wuhan were advised to self-isolate, "stay at home, not go to work, school or public places, not use public transport or taxis, ask friends, family members or delivery services to do errands",[156] and call NHS 111 if they had arrived in the UK in previous 14 days, regardless of whether they were unwell or not.[155] Further cases in early February prompted the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Matt Hancock, to announce the Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020.[54] Daily updates have been published by the DHSC.[54] NHS Digital in the meanwhile, have been collecting data.[157]

On 25 February 2020, the UK's CMOs advice for all travellers (unwell or not) who had returned to the UK from Hubei province in the previous 14 days, Iran, specific areas designated by the Italian government as quarantine areas in northern Italy and special care zones in South Korea since 19 February, to self-isolate and call NHS 111.[47] This advice was also advocated for any person who has flu-like symptoms with a history of travelling from Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and areas in Italy north of Pisa, Florence and Rimini, returning to the UK since 19 February. Later, self-isolation was recommended for anyone returning from any part of Italy from 9 March.[54][47]

Initially, Prime Minister Boris Johnson largely kept Britain open, resisting the kind of lockdowns seen elsewhere in Europe. In a speech on 3 February, Johnson's main concern was that the "coronavirus will trigger a panic and a desire for market segregation that go beyond what is medically rational to the point of doing real and unnecessary economic damage."[158] On 11 February, a "senior member of the government" told the ITV journalist Robert Peston that "If there is a pandemic, the peak will be March, April, May" and, further, that "the risk is 60% of the population getting it. With a mortality rate of perhaps just over 1%, we are looking at not far off 500,000 deaths."[159]

On 13 March, UK Government Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance told BBC Radio 4 one of "the key things we need to do" is to "build up some kind of herd immunity so more people are immune to this disease and we reduce the transmission".[160] This involves enough people getting infected, upon which they develop immunity to the disease.[161][162] Vallance said 60% of the UK's population will need to become infected for herd immunity to be achieved.[163][162] This stance was criticised by experts who said it would lead to hundreds of thousands deaths and overwhelm the NHS. More than 200 scientists urged the government to rethink the approach in an open letter.[164] Subsequently, Health Secretary Matt Hancock said that herd immunity was not a plan for the UK, and the Department of Health and Social Care said that "herd immunity is a natural byproduct of an epidemic".[165] On 4 April, The Times reported that Graham Medley, a member of the UK government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), was still advocating a "herd immunity" strategy.[166] There was a letter published in The Lancet on 17 March calling on the government to openly share its data and models as a matter of urgency.[167]

On 2 March, Johnson said in an interview with BBC News: "The most important thing now is that we prepare against a possible very significant expansion of coronavirus in the UK population". This came after the 39th case in the UK was confirmed and over a month after the first confirmed case in the UK.[168] The same day, a BBC One programme Coronavirus: Everything You Need to Know addressed questions from the public on the outbreak.[169] The following day, the Coronavirus Action Plan was unveiled.[54] The next day, as the total number of cases in the UK stood at 51, the government declared the coronavirus pandemic as a "level 4 incident",[170] permitting NHS England to take command of all NHS resources.[170][171] Planning has been made for behaviour changing publicity including good hygiene and respiratory hygiene ("catch it, bin it, kill it"),[172] a measure designed to delay the peak of the infection and allow time for the testing of drugs and initial development of vaccines.[154] Primary care has been issued guidance.[173]

Public Health England has also been involved with efforts to support the British Overseas Territories against the outbreak.[174][175]

On 27 March, Johnson said he had contracted coronavirus and was self-isolating, and that he would continue to lead the Government's response to coronavirus through video conference.[79] On the evening of 5 April the Prime Minister was admitted to hospital for tests.[176] The next day he was moved to the intensive care unit at St Thomas' Hospital, and First Secretary of State Dominic Raab deputised for him.[177]

Progression between phases

On 12 March, the government announced it was moving out of the contain phase and into the delay phase of the response to the coronavirus outbreak. The announcement said that in the following weeks, the government would introduce further social distancing measures for older and vulnerable people, and asking them to self-isolate regardless of symptoms. It announcement sidd that if the next stage were introduced too early, the measures would not protect at the time of greatest risk but they could have a huge social impact. The government said that its decisions were based on careful modelling and that government measures would only be introduced that were supported by clinical and scientific evidence,[178]

Classification of the disease

From 19 March, Public Health England, consistent with the opinion of the Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens, no longer classified COVID-19 as a "High consequence infectious disease" (HCID). This reversed an interim recommendation made in January 2020, due to more information about the disease confirming low overall mortality rates, greater clinical awareness, and a specific and sensitive laboratory test, the availability of which continues to increase. The statement said "the need to have a national, coordinated response remains" and added, "this is being met by the government's COVID-19 response". This meant cases of COVID-19 are no longer managed by HCID treatment centres only.[20]

Communications

On 16 March, the UK government started holding daily press briefings. The briefings were to be held by the Prime Minister or government ministers and advisers. The government had been accused of a lack of transparency over their plans to tackle the virus.[179] Daily briefings were also held by the administrations of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.[180] The speakers at the daily press briefings were accompanied by sign language interpreters. British sign language is a recognised language in Scotland and Wales, with interpreters standing 2 metres behind Ministers. Northern Ireland's briefings had both British and Irish Sign Language interpreters who were shown on a small screen in the press conference room. The UK briefing did not have an interpreter in the room or on a screen leading to a twitter campaign about the issue. The UK government reached an agreement to have the press conferences signed on the BBC News Channel and on iPlayer in response to the campaign.[181] In response to this a petition was created by Sylvia Simmonds that required the UK government to use sign language interpreters for emergency announcements.[182] Legal firm, Fry Law looked to commence court proceedings as they said the government had broken the Equality Act 2010, but also said that the government was doing the bare minimum and were crowdfunding to cover the government's legal costs if they lost.[181]

On 24 March, all major mobile telephony providers, acting upon a government request, sent out an SMS message to each of their customers, with advice on staying isolated.[183] This was the first ever use of the facility.[183] Although the government in 2013 endorsed the use of Cell Broadcast to send official emergency messages to all mobile phones, and has tested such a system, it has never actually been implemented. Backer Toby Harris said the government had not yet agreed upon who would fund and govern such a system.[184][185]

Prior pandemic planning

The UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy was published in 2011 and updated in 2014,[186] alongside a review of the available medical and social countermeasures .[187] Pandemic flu guidance was published in 2013 and updated in 2017 covering guidance for local planners, business sectors, and an ethical framework for the government response. The guidance stated:[188]

There are important differences between 'ordinary' seasonal flu and pandemic flu. These differences explain why we regard pandemic flu as such a serious threat. Pandemic influenza is one of the most severe natural challenges likely to affect the UK.

In June 2020 the Permanent Secretary at the Treasury Tom Scholar and the Cabinet Office Permanent Secretary Alex Chisholm told the Public Accounts Committee that in 2016 the government simulated an international flu outbreak, but the civil service did not subsequently create a plan for dealing with the pandemic's effects on the economy.[189]

Regulations and legislation

The government published the Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020 on 10 February 2020, a statutory instrument covering the legal framework behind the government's initial containment and isolation strategies and its organisation of the national reaction to the virus for England.[190] Other published regulations include changes to Statutory sick pay (into force on 13 March),[191] and changes to Employment and Support Allowance and Universal Credit (also 13 March).[192]

On 19 March, the government introduced the Coronavirus Act 2020, which grants the government discretionary emergency powers in the areas of the NHS, social care, schools, police, the Border Force, local councils, funerals and courts.[193] The act received royal assent on 25 March 2020.[194]

Closures to pubs, restaurants and indoor sports and leisure facilities were imposed via the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Business Closure) (England) Regulations 2020.[195]

The restrictions on movements, except for allowed purposes, are:

- Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020[196] (and subsequent amendments)

- Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Restrictions) (Scotland) Regulations 2020[197]

- Health Protection (Coronavirus Restrictions) (Wales) Regulations 2020[198]

- The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020[199]

In England from 15 June 2020, the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Wearing of Face Coverings on Public Transport) (England) Regulations 2020 require travellers on public transport to wear a face covering.[200]

Criticism of the UK Government's response

There has been criticism of the UK Government's response. In late March Dr. Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet told BBC's Question Time that "we knew in the last week of January that this was coming. The message from China was absolutely clear that a new virus with pandemic potential was hitting cities. ... We knew that 11 weeks ago and then we wasted February when we could have acted."[201] Dr. Anthony Costello, a former WHO director, made a similar point in April, saying: "We should have introduced the lockdown two or three weeks earlier. ... It is a total mess and we have been wrong every stage of the way." He also said that "they keep talking about flattening the curve which implies they are seeking herd immunity."[202] And David King, the former Chief Scientific Advisor, said: "We didn't manage this until too late and every day's delay has resulted in further deaths."[203]

In May, Sir Lawrence Freedman, writing for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, accused the government of following public opinion instead of leading it when taking the lockdown decision; and of missing the threat to care homes.[204] At Prime Minister's Questions on 13 May, Labour Party leader Keir Starmer accused Boris Johnson of misleading the Commons in relation to care homes.[205][206]

Criticisms from within the Government have been largely anonymous. On 20 April, a No. 10 adviser was quoted by The Times saying: "Almost every plan we had was not activated in February. ... It was a massive spider's web of failing." The same article said Boris Johnson did not attend any of the five coronavirus COBR meetings held in January and February.[207] On The Andrew Marr Show, Minister for the Cabinet Office Michael Gove said it was normal for prime ministers to be absent as they are normally chaired by the relevant department head, who then reports to the PM. The Guardian said the meetings are normally chaired by the PM during a time of crisis and later reported that Johnson did attend one meeting "very briefly".[208]

According to an April survey carried out by YouGov, three million adults went hungry in the first three weeks of lockdown, with 1.5 million going all day without eating.[209][210] Tim Lang, professor of food policy at City University, London, said that "borders are closing, lorries are being slowed down and checked. We only produce 53% of our own food in the UK. It's a failure of the government to plan."[211]

When Johnson announced plans on 10 May to end the lockdown, some experts were even more critical. Anthony Costello warned that Johnson's "plans will lead to the epidemic returning early [and] further preventable deaths,"[212] while Devi Sridhar, chair of global public health at the University of Edinburgh, said that lifting the lockdown "will allow Covid-19 to spread through the population unchecked. The result could be a Darwinian culling of the elderly and vulnerable."[213]

Martin Wolf, chief commentator at the Financial Times wrote that "the UK has made blunder after blunder, with fatal results".[214] Lord Skidelsky, a former Conservative, said that government policy was still to encourage "herd immunity" while pursuing "this goal silently, under a cloud of obfuscation".[215] The Sunday Times said: "No other large European country allowed infections to sky-rocket to such a high level before finally deciding to go into lockdown. Those 20 days of government delay are the single most important reason why the UK has the second highest number of deaths from the coronavirus in the world."[216]

Scottish Government

On 28 April the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, advised the voluntary use of non-medical grade cloth face masks in Scotland to be used in enclosed spaces such as shops and public transport, but not generally in public (excluding those who are under two years old or who have respiratory illnesses such as asthma). Sturgeon noted their limitation and said co-operation with the face mask guidance was voluntary.[217] This is in contrast to advice given by Boris Johnson and the UK government.[218]

Lifting lockdown

In mid-April a member of the Cabinet told The Telegraph that there was no exit plan yet.[219] Several members of the UK government stated that it was not possible to draw up a definitive plan on how to exit lockdown as it is based on scientific advice.[220]

In early May, research was published which concluded that if the most vulnerable (the elderly and those with certain underlying illnesses) were completely shielded, the lockdown could mostly be lifted, avoiding "a huge economic, social and health cost", without significantly increasing severe infections and deaths.[221] It also recommended regular testing and contact tracing.[222][223]

On 8 May the Welsh Government relaxed restrictions on exercise and allowed some garden centres and recycling facilities would reopen.[224] Nicola Sturgeon stated that she wanted all nations to make changes together as it would give the public a clear and consistent message.[225] Boris Johnson acknowledged different areas move at slightly different speeds with actions based on the science for each area.[226] Scotland announced a similar measure in terms on exercise as Wales, to go live on the same day.[227]

Johnson made a second televised address on 10 May, changing the slogan from 'Stay at Home' to 'Stay Alert'. He also outlined how restrictions might end and introduced a COVID-19 warning system.[138] Additionally measures were announced stating that the public could exercise more than once a day in outdoor spaces such as parks, could interact with others whilst maintaining social distance and drive to other destinations from 13 May in England.[228] This was leaked to the press[229][230] and criticised by leaders and ministers of the four nations, who said it would cause confusion.[231] The leaders of Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales said they would not adopt the new slogan.[232][233] The Welsh Health Minister Vaughan Gething said that the four nations had not agreed to it and the Scottish Health Secretary Jeane Freeman said that they were not consulted on the change.[139][234] Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said that the new message "lacked clarity".[235] The Guardian were told that neither Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer for England, or Sir Patrick Vallance, government's chief scientific adviser, had given the go ahead for the new slogan. Witty later said at a Downing Street press conference that "Neither Sir Patrick nor I consider ourselves to be comms experts, so we’re not going to get involved in actual details of comms strategies, but we are involved in the overall strategic things and we have been at every stage." The slogan was criticised by members of SAGE.[236] Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said: "We mustn't squander progress by easing up too soon or sending mixed messages. People will die unnecessarily."[237]

The next day the government published a 60-page roadmap of what exiting lockdown could look like.[140] A document was additionally published outlining nine points which applied to England, with an update of measures from 13 May.[238] As the rules between England and Wales were different in terms of exercise, many officials warned against the public driving to destinations in Wales for exercise.[239] The Counsel General for Wales, Jeremy Miles, said visitors could be fined if they drove into Wales for leisure.[139] Sturgeon gave a similar warning about driving into Scotland.[240] She additionally said that politicians and the media must be clear about what they are saying for different parts of the UK after Johnson's address did not state which measures only applied to England.[228][241][242] On 17 May, Labour leader Keir Starmer called for a 'four-nation' unified approach.[243] Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham said that there was a risk of national unity in ignoring the different demands of regions in England.[244][245] Boris Johnson acknowledged the frustrations in some of the rules and said that "complicated messages were needed during the next phase of the response and as restrictions changed."[246]

The Northern Ireland Executive published a five-stage plan for exiting lockdown on 12 May, but unlike the plans announced in England the plans did not include any dates of when steps may be taken.[247][248][232] An announcement was made on 14 May that garden centres and recycling centres would reopen on Monday in the first steps taken to end the lockdown in Northern Ireland.[249][247][248][232] An announcement was made on 14 May that garden centres and recycling centres would reopen on Monday in the first steps taken to end the lockdown in Northern Ireland.[249]

On 15 May, Mark Drakeford announced a traffic light plan to remove the lockdown restrictions in Wales, which would start no earlier than 29 May.[250][251]

National health services response

Healthcare in the UK is a devolved matter, with England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales each having their own systems of publicly funded healthcare, funded by and accountable to separate governments and parliaments. As a result of each country having different policies, laws and priorities, a variety of differences now exist between these systems.[252][253]

Equipment

On 16 March, Boris Johnson held a conference call with business leaders and set them the target of delivering 30,000 ventilators in a fortnight; the government also declined to join an emergency European Union scheme to procure ventilators and other emergency equipment like personal protective equipment (PPE) for hospital staff, saying the UK was no longer part of the EU and that this was area in which it was making its own efforts.[254] Existing ventilator stocks stood at 5,900 at the beginning of the outbreak.[255]

On 16 March, primary care magazine Pulse reported doctors were receiving out-of-date PPE that had had its 2016 use-by date covered with a sticker saying "2021".[256] In response, the government offered reassurance that this was safe.[257] Earlier in the month, in response to a survey of Pulse's readership, two of five GPs reported they still did not have PPE to protect them from coronavirus.[256] Some of these concerns were raised with Johnson during Prime Minister's Questions, to which the Prime Minister replied the UK had "stockpiles" of PPE.[258] The same day, the Doctors' Association reported NHS staff felt they were being put at risk due to lack of PPE.[259]

On 22 March, in a letter with 3,963 signatures published in The Times, NHS staff asked Johnson to "protect the lives of the life-savers" and resolve the what they saw as the "unacceptable" shortage of protective equipment.[260][261] On 23 March, in an effort to meet demand and due to concerns about the rising number of medics becoming ill after exposure to the virus, the NHS asked DIY stores to donate PPE for use by NHS staff.[262] Hancock said there were "challenges" with supplying PPE to NHS staff and said a million masks had been bought that weekend.[263] The following day, the government said there was enough PPE for everyone in the NHS who needed it; this was contradicted by the Royal College of Nursing,[264] and the British Medical Association (BMA), which warned that without enough PPE, doctors would die.[265]

.jpg)

On 31 March, 10,000 health workers wrote to the prime minister demanding better safeguards, including the right PPE.[266] On 1 April, the government said 390 million pieces of PPE had been distributed to the health service in the past fortnight. The Royal College of Midwives (RCM)[267] and the BMA said the supplies had yet to reach medical staff.[268] The RCM, in a joint statement with unions, including Unite, Unison and the GMB, said the lack of PPE was now 'a crisis within a crisis'.[267]

On 29 March, the government issued a specification for the "minimally clinically acceptable" manufacture and use of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) machines.[269]

On 10 April the UK Government sent out a document to PPE suppliers informing them that suppliers of certain medical equipment, including protective masks, gloves and aprons, must be registered with the Care Quality Commission, which regulates all health and social care services in England only. There was not a similar agreement in place between suppliers and Care Inspectorate Wales or the Care Inspectorate of Scotland.[270][271] The Welsh Government advised care home providers that they should order through their local council, while Plaid Cymru leader Adam Price lodged a formal complaint with the European Union over the issue.[271] The manager of two care homes in Gwynedd, Wales was told by two suppliers that they would only sell to care homes in England.[272] The chief executive of the care home umbrella group Scottish Care said that the UK's four largest PPE suppliers had said they were not distributing to Scotland because their priority was going to be "England, the English NHS and then English social care providers".[273] The UK government reported that it had not instructed any company to prioritise PPE for any nation.[273] Healthcare supplier Gompels' website said at the time that "These restrictions are not something we have decided, they are a criteria given to us by Public Health England".[274]

A BBC Panorama episode, Has the government failed the NHS?, broadcast on 27 April, said the government had been counting PPE items in a way that artificially inflated the total. Gloves were counted individually, rather than as pairs, for instance, and non-PPE items, such as paper towels and detergent, were included in the figure.[275] The programme also said the government was changing the guidance on what PPE was appropriate for medical staff to wear when treating COVID-19 patients, not according to best protective procedure, but according to the stock available.[276] The programme also said that, in the years before the pandemic, the government had ignored expert advice and failed to stockpile essential items.[276] Due to lack of stock, in May an NHS trust prioritised anti-bacterial ventilator filters for coronavirus patients over others. .[277]

Staffing

On 1 March, Hancock said retired NHS staff might be asked to return to work to help with the crisis.[278] The request was issued on 19 March and included final year medical students.[279] On 29 March, Boris Johnson announced that more than 20,000 former NHS staff were returning to work in response to the pandemic.[280]

On 21 March, the NHS had agreed to use, at cost price, almost the entire private health system, bringing 20,000 medical staff into the national effort.[281]

On 24 March, Matt Hancock launched a scheme to recruit 250,000 volunteers to support the NHS through the pandemic.[282] The volunteers would carry out jobs like collecting and deliver shopping, medication or "other essential supplies" for people in isolation; transporting equipment and medication between NHS services; transporting medically fit patients and providing telephone support to people at risk of loneliness because of self-isolation.[283] The target was surpassed in 24 hours and was raised to 750,000.[284] The scheme was paused on 29 March after the new target was reached.[283]

Temporary critical care hospitals

In Northern Ireland capacity was upgraded at Belfast City Hospital, while in Scotland, NHS Louisa Jordan was established in Glasgow by NHS Scotland.

NHS England established temporary "Nightingale" hospitals in London, Birmingham, Manchester and Harrogate. Dragon's Heart Hospital was set up at the Principality Stadium in Cardiff, Wales.

Testing and monitoring

Shortly after confirming that the cause of the cluster of pneumonia in Wuhan was a new coronavirus, Chinese authorities had shared its genetic sequence for international developments of diagnostic kits.[37] By 10 January,[285] the UK had developed a prototype specific laboratory test for the new disease, performed on a sample from the nose, throat, and respiratory tract and tested at PHE's public health laboratory at Colindale in London.[22] Testing of patients began within days,[286] and by 3 February 326 tests had been performed in the UK.[155] Over the following few weeks, PHE made the test available to 12 other laboratories in the UK, making it possible to test 1,000 people a day.[22][287]

As of 12/13 March 2020, 29,764 tests had been conducted in the UK, corresponding to 450.8 tests per million people.[288] On 24 March, Matt Hancock said the government had bought 3.5m kits that would test if a person has already had COVID-19; no date was given for their arrival. These tests would allow people to know if they were immune and therefore able to "go back to work".[289] It was later found when the kits, which had cost at least £16 million, were tested, they did not meet the required specifications.[290] Hancock announced on 28 March that 10,000 tests a day were now being processed; the actual figure was 5,000.[291][292] As of 31 March 143,186 people had been tested.[54]

The UK government and Public Health England were criticised for what some saw as a failure to organise mass testing. On 28 March the editor-in-chief of The Lancet published a condemnation of what he saw as government inaction and ignoring of WHO advice.[293] On 31 March former WHO director Anthony Costello, following WHO advice that countries should "test, test, test", said the key to the UK's transitioning out of lockdown was mass testing, and that the UK had the capacity to reach the level of testing being carried out by Germany (70,000 tests a day, compared to the UK's 5,000) but the government and Public Health England (PHE) had been too slow and controlling to organise.[294] The day after, Conservative MP Jeremy Hunt, chair of the Health and Social Care Select Committee and former Health Secretary, said it was "very worrying" that the government had not introduced mass testing because doing so had been "internationally proven as the most effective way of breaking the chain of transmission".[295] On 2 April, The Telegraph reported that one of the Government's science advisers, Graham Medley, said "mass public testing has never been our strategy for any pandemic." Medley also said the Government "didn't want to invest millions of pounds into something that is about preparedness".[296]

The government launched a booking portal for people to be tested for COVID-19. The governments of Scotland and Northern Ireland governments signed up to use the portal that England were using. The Welsh Government went on to partner with Amazon to create a portal. Later this was scrapped with the Welsh Government citing issues around collecting of data having been resolved with the UK government's portal and now wanted to use it, having only released their version across south east Wales.[297]

In May, the Department of Health and Social Care and Public Health England confirmed that two samples taken from single subjects, such as in the common saliva and nasal swab test, are processed as two separate tests. This, along with other repeated tests such as checking a negative result, led to the daily diagnostic test numbers being over 20% higher than the number of people being tested.[298]

On 18 May testing was extended to anyone over the age of five after the governments of all four nations agreed to the change.[299]

England

Following 300 staff being asked to work from home on 26 February in London, while a person was awaiting a test result for the virus, PHE expanded testing around the UK to include people with flu-like symptoms at 100 GP surgeries and eight hospitals: the Royal Brompton and Harefield, Guy's and St Thomas' and Addenbrookes Hospital, as well as hospitals at Brighton and Sussex, Nottingham, South Manchester, Sheffield, Leicester.[300][301]

Drive-through screening centres were set up by Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust at Parsons Green Health Centre on 24 February 2020,[302] A further drive-through testing station was set up by the Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust at a site just off the A57 Sheffield Parkway dual-carriageway on 10 March; in this case, patients ringing NHS 111 with coronavirus-like symptoms in the Sheffield area will be told to drive, if possible, to the testing centre at an allotted time.[303]

On 11 March, NHS England announced that testing in NHS laboratories would increase from testing 1,500 to 10,000 per day.[304] The test consists of taking a sample from the nose, throat, deeper lung samples, blood or stool, and transporting the packed samples to the listed PHE regional laboratory designated for the referring laboratory region.[305][306] On 14 May PHE approved an antibody test by Swiss company Roche.[307] Abbott Laboratories said that they also had an antibody test approved by the public health boards of England, Scotland and Wales.[308]

Scotland

On 29 February drive-through testing was set-up by NHS Lothian at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh.[309] On 1 March 2020 it was reported that surveillance was shortly to be extended to some hospitals and GP surgeries in Scotland.[310]

Scotland were developing their own contact tracing system, with contact tracing being done by telephone rather than an app.[311][312]

Wales

On 21 March, Welsh Government Health Minister Vaughan Gething said that the target was 9,000 tests by the end of April. Public Health Wales Chief Executive Tracey Cooper confirmed on 7 May that Wales was to receive an extra 5,000 COVID-19 test kits per day, before the UK Government stepped in and stopped them. The Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche Diagnostics and the Welsh Government had a gentleman's agreement, verbally and through emails. Dr Cooper blamed the UK government "for gazumping Wales's Covid-19 testing deal" with Roche; this left Wales only able to carry out 800 tests a day. Public Health England said that it had not interfered with any contract but said "The UK Government recently asked us to establish a partnership with Roche to support increased diagnostic testing in the UK for Covid-19."[313][314]

On 21 May 2020 the Welsh Government announced that one of the new antibody blood tests for the SARS-CoV-2 virus is being produced by Ortho Clinical Diagnostics (OCD) at Pencoed, Wales, in partnership with Public Health Wales. The test will be rolled out, prioritised and managed and will also be available in care homes. According to Health Minister Vaughan Gething, this test is an important part of the "Test, Trace, Protect" strategy which will help Wales come out of lockdown.[315]

Mobile phone app

On 4 May, a test version of the NHS's contact tracing app was released.[316][317] The app is being trialled on the Isle of Wight.[316][317]

Matthew Gould, CEO of NHSX, the government department responsible for the app, said the data would be accessible to other organisations for legitimate public health reasons, but could not list which.[318] Faculty, a company linked to Cambridge Analytica and Palantir, also linked to Cambridge Analytica,[319] worked on the app.[320] The data collected would be handled according to the data access regulations and would be held in a centralised repository.[321][319][322] Over 150 of the UK's security and privacy experts warned the app's data could be used by 'a bad actor (state, private sector, or hacker)' to spy on citizens.[323][324] Fears were discussed by the House of Commons' Human Rights Select Committee about plans for the app to record user location data.[316] Parliament's Joint Committee on Human Rights said the app should not be released without proper privacy protections.[325]

The Scottish government said they would not recommend the app until they could be confident it would work and would be secure.[326] The functionality of the app was also questioned as the software's use of Bluetooth required the app to be constantly running, meaning users could not use other apps or lock their device if the app was to function efficiently.[317]

Digital inclusion advocates told the Culture, Media and Sport Committee in May that there was a digital divide with the app, with many people missing out due to not having access to the Internet or having poor IT skills. The advocates said that 64% of the population who had not used the Internet were over the age of 65, and that 63% of the population who did not know how to open an app were under the age of 65.[327] It was reported by the Financial Times that a second app was in development using technology from Apple and Google.[328][329] The digital skills advocacy group FutureDotNow is running a campaign to provide connectivity to excluded households.[330]

On 18 June, Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced development would switch to the Apple/Google system after admitting that Apple's restrictions on usage of Bluetooth prevented the app from working effectively.[331]

Research and innovation

Sociological research

In March 2020, UK Research and Innovation announced[332] the launch of a website to explain the scientific evidence and the facts about the virus, the disease, the epidemic, and its control, in a bid to dispel misinformation. The editorial team come from University of Oxford, European Bioinformatics Institute, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Imperial College London, University of Glasgow and King's College London.[333]

Research carried out by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford concluded that of 225 examples false or misleading claims about coronavirus 88% of the claims had appeared on social media platforms, with 9% of the claims on television and 8% in news outlets.[334][335] One such claim about 5G mobile phone masts which began on social media, ended up with arson attacks on masts.[336] A YouGov survey for the Institute concluded that 54% of the people polled thought that the UK government was doing a good job of responding to the pandemic. A quarter of those surveyed felt that the pandemic had been exaggerated by the media indicating that criticism could be eroding trust.[337][338][339] An earlier Sky News survey also concluded that people surveyed thought that the media were being overly critical of the government.[339][340] The Sky News survey simply asked the public about trust in journalists. Polls by YouGov, the Reuters Institute, Survation, Ipsos MORI and research by Ofcom, concluded that broadcasters and newspapers were widely considered to be the most trusted sources of information on pandemic.[339] According to research from Ofcom, the BBC was the most trusted broadcaster on the pandemic, followed by ITV, Sky, Channel 4 and Channel 5.[341][339] The newspapers The Guardian, Financial Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Times were ranked with trust levels similar to that of the television broadcasters during the pandemic.[339][342] A survey by YouGov for the Reuters Institute concluded that the BBC's output dominated online news coverage in the UK with 36% of the population saying that they had been on the corporation's website to consume news. Around 16% polled said that they had visited The Guardian's website, with Sky News and MailOnline in joint third place with 9% of those polled saying that they had visited their sites.[342] A few weeks after the start of the pandemic Reuters Institute and Ofcom both said that people were actively trying to avoid the news coverage about it.[342][339]

A study by a team of researchers from the University of Sheffield and Ulster University concluded that young men were more likely to break lockdown rules than women. The study concluded that those suffering from depression were more likely to break the rules. Around half of the participants said that they felt anxious during the restrictions. The team called on the government to issue better target messages for young people.[343] According to data from the National Police Chiefs' Council, two-thirds of the people who were issued fines for breaking lockdown rules in England and Wales, between 27 March and 27 April, were between the ages of 18 and 34. Approximately eight out of 10 of those who were issued fines were men.[344]

Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies concluded that children from wealthy homes were spending more time studying at home when compared to those from the poorest households.[345]

Biological research

UK Research and Innovation also announced £20 million to develop a COVID-19 vaccine and to test the viability of existing drugs to treat the virus.[346] The COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium will deliver large-scale, rapid whole genome sequencing of the virus that causes the disease and £260 million to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations to support vaccine development.[347][348] In April, the UK Government launched a task force to help develop and roll out a coronavirus vaccine.[349][350] A University of Edinburgh led study in to whether specific genes cause a predisposition into the effects that COVID-19 had on people began in May.[351][352] The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, studied whether sniffer dogs could detect coronavirus in humans.[353] Following research by King's College London of symptoms from 1.5 million suspected cases, "loss of taste or smell" was added to the NHS symptoms list.[354]

Design and innovation

In March 2020 the government asked manufacturers in the UK to help in the production of respiratory devices to help fight COVID-19.[355] Innovate UK announced £20 million funding for innovative businesses.[356] The Formula One teams and manufacturers based in the UK linked up to form "Project Pitlane."[357]

A group of engineers from Mercedes and University College London, along with staff from University College Hospital, designed and made a product known as UCL-Ventura breathing aid, which is a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approved the second model of the device. The UK Government put an order in for 10,000 devices. Mercedes made the drawings for the device available for free to help other countries fight COVID-19.[358][359] On 16 April the MHRA approved the Penlon Prima ESO2, design which was part of the stream known as VentilatorChallengeUK. The UK government ordered 15,000 of these devices.[360][361] A consortium of aerospace companies including Airbus, Meggitt, and GKN worked on scaling up production of an existing design.[362][363] In April this design was approved by the MHRA and an order for 15,000 units was placed.[364] Other designs by JCB, Dyson and BlueSky were not taken forward.[365] Eight other designs had their support ended by the UK government.[365][366][367][359]

A CPAP device, known as a Covid emergency ventilator, designed by Dr Rhys Thomas, a consultant anaesthetist at Glangwili General Hospital in Carmarthen, was given the go-ahead by the Welsh Government.[368] The machine, designed in a few days was used on a patient in mid-March, and subsequently funded by the Welsh Government. In early April, it was approved by the MHRA. Production is by CR Clarke & Co in Betws, Carmarthenshire.[369][370]

Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) produced a reusable visor with the first deliveries just before Easter, and shared the designs to allow wider manufacture.[371][372] The Royal Mint manufactured medical visors for medical staff working during the pandemic.[373][374]

Economic impact

The pandemic was widely disruptive to the economy of the United Kingdom, with most sectors and workforces adversely affected. Some temporary shutdowns became permanent; some people who were furloughed were later made redundant.

Social impact

Arts and entertainment

Music

On 13 March, BBC Radio 1 cancelled its Big Weekend music festival, scheduled to take place at the end of May.[375] Other music events to be cancelled included the C2C: Country to Country festival,[376][377] the Glastonbury Festival,[378] the Isle of Wight and Download music festivals,[379] the Cambridge Folk Festival,[380] and the Love Supreme Jazz Festival.[381] The organisers of the Download festival subsequently announced plans to hold a virtual festival to be held on the dates it would have happened, and featuring streamed performances and interviews.[382] Big Weekend organisers decided to run an alternative event called Big Weekend UK 2020. Stars appeared on one of 5 virtual stages and performed from their homes, with the event also featuring past performances from previous Big Weekend events.[383]

Among the artists and bands to postpone or cancel UK gigs or tours were Avril Lavigne and The Who.[377][384] Other, including Chris Martin of Coldplay, and Yungblud responded to the situation by live-streaming gigs through social media.[385] Various musicians announced free gigs for NHS staff.[386][387]

Visual arts

A number of artists began painting portraits of NHS workers, as a way of organising their work and thanking the for it.[388] An exhibition is planned, once the pandemic subsides.[388]

Theatre and cinema

On 15 March, London's Old Vic became the first West End theatre to cancel a performance when it ended its run of Samuel Beckett's Endgame two weeks early.[389] On 16 March, other theatres in London, as well as elsewhere around the UK, closed following Boris Johnson's advice that people should avoid such venues.[390] On 17 March, cinema chains Odeon, Cineworld, Vue and Picturehouse announced they would be closing all their UK outlets.[391] On 1 April, the 2020 Edinburgh festivals, planned for August, were cancelled.[392]

On 26 March the National Theatre launched National Theatre at Home, a two-month programme whereby a different production from its archives would be streamed for free each week. The project began with Richard Bean's comedy One Man, Two Guvnors, featuring James Corden.[393]

Television and radio

Television programmes to be affected included forthcoming series of Peaky Blinders and Line of Duty, which had their filming schedules delayed.[394] On 13 March, ITV announced that the 2020 series finale of Ant & Dec's Saturday Night Takeaway, scheduled to be broadcast from Walt Disney World in Florida would no longer go ahead after the resort announced its intention to close as a precautionary measure.[395] On 16 March, ITV announced that the filming schedule for its two soaps, Coronation Street and Emmerdale had not been affected by the pandemic,[394] but filming ceased on 23 March.[396] On 18 March ITV announced the semi-final of the ninth series of The Voice UK, scheduled for 28 March, would be postponed until later in the year.[397]

On 16 March, the BBC delayed implementation of its planned changes to TV licences for those aged over 75 from June to August.[398] On 25 March the BBC also announced that it would delay its plans to cut 450 news jobs due to the pressure of covering the pandemic.[399]

On 17 March, the BBC announced major changes to the schedule across the network. While some programmes were suspended, others such as Newsnight and The Andrew Marr Show continued with a smaller number of production staff. Some podcasts were also suspended.[400] On 18 March it was announced that filming of soap operas and regular dramas would be suspended.[401] The BBC also said it would show more educational programmes to cater for children not attending school,[402] and more programmes focused on health, fitness, education, religion and food recipes.[397] On 23 March, ITV ceased the live broadcasting of two programmes.[396]

On radio, some BBC World Service programmes were suspended. Summaries on Radio 2, Radio 3, Radio 4 and 5 Live were merged into a single output, with BBC 6 using the same script. The BBC Asian Network and Newsbeat worked together to maintain production of stories.[400] On 18 March, the BBC announced that its local radio stations in England would broadcast a virtual church service, led initially by the Archbishop of Canterbury, but with plans to expand religious services to cover other faiths.[397] On the same day Radio News Hub, a radio news bulletin provider based in Leeds, announced that it would produce a daily ten-minute programme giving a round-up of information about the pandemic, and that would be made available free of charge to radio stations.[403] On 28 March, BBC Local Radio announced that it had teamed up with manufacturers, retailers and the social isolation charity WaveLength to give away free DAB radios to people over 70.[404]

Defence

The coronavirus pandemic affected British military deployments at home and abroad. Training exercises, including those in Canada and Kenya, had to be cancelled to free up personnel for the COVID Support Force.[405] The British training mission in Iraq, part of Operation Shader, had to be down-scaled.[406] An air base supporting this military operation also confirmed nine cases of coronavirus.[407] The British Army paused face-to-face recruitment and basic training operations, instead conducting them virtually.[408] Training locations, such as Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and HMS Raleigh, had to adapt their passing out parades. Cadets involved were made to stand 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) apart in combat dress and there were no spectators in the grandstands.[409][410] Ceremonial duties[411][412] and displays were stopped.[413][414] The British Army deployed two experts to NATO to help counter disinformation around the pandemic.[415] The Government's defence and security review, named the Integrated Review, was delayed.[416]

In March 2020, following requests for military aid to the civil authorities, the Ministry of Defence announced the formation of the COVID Support Force under the Standing Joint Commander (UK), Lieutenant General Tyrone Urch at Aldershot to support public services and civil authorities in tackling the pandemic. Unlike the police and some other civil agencies, members of the armed forces (during peacetime) have no powers over and above those of ordinary citizens.[417][418] The support force initially consisted of 20,000 personnel but later grew to amount to 23,000.[419] Two military operations; Operation Rescript, based in the UK, and Operation Broadshare, focused on overseas defence activities, were launched.[420] Chief of the Defence Staff Nick Carter ordered the military to prepare for a "six month" operation and to be on an "operational footing" by mid-April.[421] The COVID Support Force was initially tasked with driving oxygen tankers for the NHS, as well as delivering medical supplies, including PPE, to hospitals.[417][422] Prior to the announcement of the COVID Support Force, the armed forces had assisted the British government in repatriating British citizens from affected areas, including China and Japan.[423] The Royal Air Force also repatriated British and EU citizens from Cuba.[424] The armed forces additionally assisted in the transportation of coronavirus patients around the UK, including Shetland and the Isles of Scilly.[425][426] On 23 March 2020, Joint Helicopter Command began assisting the coronavirus relief effort by transporting people and supplies. Helicopters were based at RAF Leeming to cover Northern England and Scotland, whilst helicopters based at RAF Benson, RAF Odiham and RNAS Yeovilton supported the Midlands and Southern England.[427]