W. Ian Lipkin

W. Ian Lipkin (born 1952) is the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a professor of Neurology and Pathology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. Lipkin is also director of the Center for Infection and Immunity, an academic laboratory for microbe hunting in acute and chronic diseases.

W. Ian Lipkin | |

|---|---|

.jpg) W. Ian Lipkin | |

| Born | 1952 (age 67–68) |

| Education | University of Chicago Laboratory School |

| Alma mater | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Website | www.mailman.columbia.edu |

Education

Lipkin was born in Chicago, Illinois, where he attended the University of Chicago Laboratory School and was president of the student board in 1969. He relocated to New York and earned his BA from Sarah Lawrence College in 1974. At Sarah Lawrence, he "felt that if I went straight into cultural anthropology after college I’d be a parasite. I’d go someplace, take information about myths and ritual, and have nothing to offer. So I decided to become a medical anthropologist and try to bring back traditional medicines. Suddenly I found myself in medical school."[1] Returning to his hometown Chicago, Lipkin earned his MD from Rush Medical College, in 1978. He then became a clinical clerk at the UCL Institute of Neurology in Queen Square, London, on a fellowship, and an intern in Medicine at University of Pittsburgh (1978–1979). He completed a residency in Medicine at University of Washington (1979–1981), and completed a residency in Neurology at University of California, San Francisco (1981–1984). He conducted postdoctoral research in microbiology and neuroscience at The Scripps Research Institute, from 1984 to 1990, under the mentorship of Michael Oldstone and Floyd Bloom. In his six years at Scripps, Lipkin became a senior research associate upon completing his postdoctoral work, and was president of the Scripps' Society of Fellows in 1987.

Career

Lipkin has earned the reputation of a "master virus hunter" for to his speed and innovative methods of identifying new viruses, and has been lauded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony S. Fauci. As director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at the Mailman School of Public Health; Lipkin, from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, has led CII researchers collaborating with researchers at Sun Yat-sen University in China. Dr. Lipkin had also advised the Chinese government and the World Health Organization (WHO) during the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak.[2][3] Dr. Lipkin described his own infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, beginning mid-March 2020, which resulted in a case of COVID-19 and necessitated his recovering from the illness at home, on the podcast This Week in Virology.[4]

Lipkin was the Louise Turner Arnold Chair in the Neurosciences[5] at the University of California, Irvine from 1990-2001 and was recruited shortly thereafter by Columbia University. He began his current tenure at Columbia as the founding director of the Jerome L. and Dawn Greene Infectious Disease Laboratory from 2002–2007, which transitioned to the John Snow Professorship he holds at present.

A physician-scientist, Lipkin is internationally recognized for his work with West Nile virus and SARS, as well as advancing pathogen discovery techniques by developing a staged strategy using techniques pioneered in his lab. These molecular biological methods, including MassTag-PCR, the GreeneChip diagnostic, and High Throughput Sequencing, are a major step towards identifying and studying new viral pathogens that emerge locally throughout the globe. A major node in a global network of investigators working to address the challenges of pathogen surveillance and discovery, Dr. Lipkin has trained over 30 internationally based scientists in these state-of-the art diagnostic techniques.

Lipkin is the director for the Center for Research in Diagnostics and Discovery (CRDD), under the NIH Centers of Excellence for Translational Research program.[6] The CRDD brings together leading investigators in microbial and human genetics, engineering, microbial ecology and public health to develop insights into mechanisms of disease and methods for detecting infectious agents, characterizing microflora and identifying biomarkers that can be used to guide clinical management. Lipkin was previously the Director of the Northeast Biodefense Center,[7] the Regional Center of Excellence in Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases which comprised 28 private and public academic and public health institutions in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Within this consortium, his research focused on pathogen discovery, using unexplained hemorrhagic fever, febrile illness, encephalitis, and meningoencephalitis as targets. He is the Principal Investigator of the Autism Birth Cohort, a unique international program that investigates the epidemiology and basis of neurodevelopmental disorders through analyses of a prospective birth cohort of 100,000 children and their parents. The ABC is examining gene-environment-timing interactions, biomarkers and the trajectory of normal development and disease. Lipkin also directs the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Diagnostics in Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, the only academic center, and one of two in the US (the other is CDC), that participates in outbreak investigation for the WHO.

Lipkin was co-chair of CDC Steering Committee of the National Biosurveillance Advisory Subcommittee (NBAS).[8] The NBAS was established in response to Homeland Security Presidential Directive 21 (HSPD-21),[9] "Public Health and Medical Preparedness."

He is Honorary Director of the Beijing Infectious Disease Center, Chair of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Institut Pasteur de Shanghai and serves on boards of the Australian Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre for Emerging Infectious Disease, the Guangzhou Institute for Biomedicine and Health, the EcoHealth Alliance,[10] Tetragenetics, and 454 Life Sciences Corporation.

Lipkin served as a science consultant for the film Contagion.[11] The film has been praised for its scientific accuracy.

Early career

While not quite a medical anthropologist, Lipkin specializes in infectious diseases and their neurological impact. His first professional publication came in 1979 during the time of his fellowship in London as a letter to the Editor at the Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine), where he poses a potential correlation between eosinopenia and bacteremia in diagnostic evaluations for a bacteremic patient.[12] While at UCL, he worked with John Newsom-Davis, who was utilizing plasmapheresis to better understand myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disease.[13]

In 1981, Lipkin began his neurology residency and worked in a local San Francisco clinic, which was about the time AIDS began to affect the local city population. Because of the social view of homosexual people at the time, very few clinicians would see patients with these symptoms. He "was watching many patients fall ill with AIDS. It took years for scientists to discover the virus responsible for the disease... 'I saw all of this, and I said, 'We have to find new and better ways to do this.'"[14] It was during this epidemic that Lipkin took the approach of looking for a virus’ genes instead of looking for antibodies in infected people as a way to speed up the diagnosis process. By the mid-1980s, Lipkin had published two papers specifically about AIDS research[15][16] and transitioned into utilizing a more pathological approach to virus identification. He identified AIDS-associated immunological abnormalities and inflammatory neuropathy, which he showed could be treated with plasmapheresis and demonstrated early life exposure to viral infections affects neurotransmitter function.

Bornavirus

In 1989, Lipkin was the first to identify a microbe using purely molecular tools.[17][18] During his time as Chair at UC Irvine, Lipkin published several papers throughout the decade dissecting and interpreting bornavirus.[19] Once it was apparent the viral infections could selectively alter behavior and steady state brain levels of neurotransmitter mRNAs, the next step was to look for infectious agents which could be used as probes to map anatomic and functional domains in the central nervous system (CNS).[20]

By the mid-1990s, it was asserted that "Borna disease is a neurotropic negative-strand RNA virus that infects a wide range of vertebrate hosts," causing "an immune-mediated syndrome resulting in disturbances in movement and behavior."[21] This led to several groups across the globe working to determine if there was a link between Borna disease virus (BDV) or a related agent and human neuropsychiatric disease.[22] The group was formally called Microbiology and Immunology of Neuropsychiatric Disorders (MIND) and the multicenter, multi-national group focused on using standardized methods for clinical diagnosis and blinded laboratory assessment of BDV infection.[23] After nearly two decades of inquiry, the first blinded case-controlled study of the link between BDV and psychiatric illness[24] was completed by the researchers at Columbia University's Center for Infection and Immunity in a joint effort that concluded there is no association between the two. Lipkin noted that "it was concern over the potential role of BDV in mental illness and the inability to identify it using classical techniques that led us to develop molecular methods for pathogen discovery. Ultimately these new techniques enabled us to refute a role for BDV in human disease. But the fact remains that we gained strategies for the discovery of hundreds of other pathogens that have important implications for medicine, agriculture, and environmental health."[25]

West Nile Virus

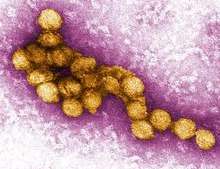

In 1999, West Nile virus was reported in two patients in Flushing Hospital Medical Center in Queens, New York. Lipkin led the team identifying West Nile virus in brain tissue of encephalitis victims in New York State[14] It was determined potential routes for the spread of West Nile virus throughout New York (and the Eastern United States) originated from predominantly mosquitoes, but also possible from infected birds or human beings. There is a high likelihood the two international airports nearby the initial reported cases were also the initial points of entry into the United States.[26] During the five years after the first reported case, Lipkin worked on a study with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Wadsworth Center at the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) to determine how a vaccine could be developed. While they had some success with the immunization of mice with prME-LPs,[27] as of 2018, there is still no human vaccine for WNV.[28]

SARS-CoV

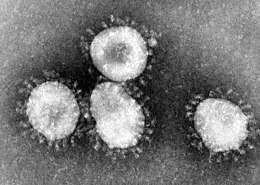

Chinese scientists first discovered the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus in February 2003, but due to initial misinterpretation of the data, the information of the correct agent associated with SARS was suppressed and the outbreak investigation had a delayed start. Advanced hospital facilities were at the greatest risk as they were most susceptible to virus transmission, so it was the "classical gumshoe epidemiology" of "contact tracing and isolation" that brought swift action against the epidemic.[29] Lipkin was requested to assist with the investigation by Chen Zhou, vice president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Xu Guanhua, minister of the Ministry of Science and Technology in China to "assess the state of the epidemic, identify the gaps in science, and develop a strategy for containing the virus and reducing morbidity and mortality."[30] This brought the development of Real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) technology, which essentially allowed for the detection of infection at earlier time points as the process, in this instance, targets the N gene sequence and amplify the analysis in a closed system. This markedly reduces the risk of contamination during processing.[31] Test kits were developed with this PCR-based assay analysis[32] and 10,000 were hand-delivered to Beijing during the height of the outbreak by Lipkin, whereupon he trained local clinical microbiologists on the proper usage. He became ill upon his return to the U.S. and was quarantined.[33]

Lipkin was asked to join the Defense Science Board Task Force on SARS Quarantine Guidance during the height of the SARS outbreak between 2003–04, to advise the U.S. Department of Defense on steps to domestically manage the epidemic. As part of the EcoHealth Alliance, Lipkin's center worked in conjunction with an NIH/NIAID grant[34] assessing bats as the reservoir for the SARS virus. 47 publications resulted from this grant, which also included assessment on Nipah, Hendra, Ebola, and Marburg viruses. This proved to be significant research on the overall study of viral reservoirs as it was determined that bats carry coronaviruses and either directly infect humans with an exchange of bodily fluid (such as a bite) or indirectly by infecting an intermediate host, such as swine.[35] Lipkin addressed a health forum in Guangzhou in January 2004 where China Daily reported him as saying: "SARS virus is probably rooted and spread by rats."[36]

In January 2020, the Chinese government awarded a medal to Lipkin, its highest honor, for his work during the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak.[3]

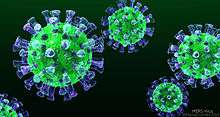

MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) was first reported in Saudi Arabia during June 2012 when a local man was initially diagnosed with acute pneumonia and later died of kidney failure. The early reports of the disease were similar to SARS as the symptoms are similar, but it was quickly determined these cases were caused by a new strain called MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Given Lipkin's expertise with the SARS outbreak in China nearly ten years prior, the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health granted Lipkin and his lab local access to animal samples related to the initial reported cases.[37] With the rare opportunity, Lipkin's team created a mobile lab able to fit in six pieces of personal luggage and was transported from New York to Saudi Arabia via commercial flight to complete the analysis of samples.[38]

It seemed unlikely that bats were directly infecting humans, as the direct physical interaction between the two is limited at best.[37] A study was completed in more local proximity, examining the diverse bat populations in southeastern Mexico and determining how diverse the viruses they carry could be.[39] However, it became apparent that dromedary camels were the intermediary in the transmission between bats and humans, since camel milk and meat are dietary staples in the Saudi Arabian region.[40] The instances of human-to-human transmission appeared to be isolated to case-patients and anyone in close direct contact with them, as opposed to a broad open-air transmission.[41] By 2017, it was determined that bats are most likely the evolutionary original source for MERS-CoV along with several other coronaviruses, though not all of those types of zoonotic viruses are direct threats to humans like MERS-CoV[42] and "[c]ollectively, these examples demonstrate that the MERS-related coronaviruses are high associated with bats and are geographically widespread."[43]

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a chronic condition characterized by extreme fatigue after exertion that is not relieved by rest and includes other symptoms, such as muscle and joint pain and cognitive dysfunction. In September 2017, the NIH awarded a $9.6 million grant to Columbia University for the "CfS for ME/CFS" intended for the pursuit of basic research and the development of tools to help both physicians and patients effectively monitor the course of the illness.[44] This collaboration effort led by Lipkin includes other institutions, such as the Bateman Horne Center (Lucinda Bateman), Harvard University (Anthony L. Komaroff), Stanford University (Kegan Moneghetti), Sierra Internal Medicine (Daniel Peterson), University of California, Davis (Oliver Fiehn), and Albert Einstein College of Medicine (John Greally), along with private clinicians in New York City.[45]

The team of researchers and clinicians initially collaborated to de-link xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus (XMRV) to ME/CFS after the NIH requested research into the conflicting reports between XMRV and ME/CFS. The group "consolidated its vision with support from the Hutchins Family Foundation Chronic Fatigue Initiative (CFI) and a crowd-funding organization, The Microbe Discovery Project, to explore the role of infection and immunity in disease and identify biomarkers for diagnosis through functional genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic discovery."[46] The project will collect a large clinical database and sample repository representing oral, fecal, and blood samples from well-characterized ME/CFS subjects and frequency-matched controls collected nationwide over a period of several years. Additionally, researchers are working with ME/CFS community and advocacy groups as the project progresses.[47]

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM)

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is a serious condition of the spinal cord with symptoms including rapid onset of arm or leg weakness, decreased reflexes, difficulty moving the eyes, speaking, or swallowing may also occur. Occasionally numbness or pain may be present and complications can include trouble breathing. In August 2019, Lipkin and Dr. Nischay Mishra published a collaborative study with the CDC in analyzing serological data for serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples of AFM patients.[48] The Lipkin team utilized high-density peptide arrays (also known as Serochips) to identify antibodies to EV-D68 in those samples. The technology was featured on the Dr. Oz Show in mid-September, illustrating how the enterovirus affects the CSF and the actual Serochip used to do the analysis.[49][50] In October, the University of California, San Francisco published a separate collaborative study with the CDC that confirmed the presence of antibodies to enterovirus in AFM patient CSF samples using phage display (VirScan).[51] "It's always good to see reproducibility. It gives more confidence in the findings for sure," commented Lipkin in an October 2019 CNN article. "This gives us more support of what we found."[52][53][54]

SARS-CoV-2

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Lipkin contributed to scientific research,[55] and led 50 to 60 CII researchers collaborating with colleagues and researchers at Sun Yat-sen University, China, to develop a "rapid and reliable" COVID-19 diagnostic test.[2] On March 24, 2020,[56] Lipkin announced that he had tested positive for coronavirus.[4] In the same episode (at 33:30 timestamp), he admitted to conspiring with fellow epidemiologists Arnold Monto and Allison Aiello to withhold publishing data from a WHO investigation which demonstrated a 60%-70% reduction in community spread of coronaviruses, and expanded that their motivation was to protect mask supplies for healthcare workers.

Fact-finding mission to China

On January 29, 2020, Lipkin flew into Guangzhou, China to learn about the outbreak of SARS-nCoV-2.[57] Lipkin worked with China CDC to access blood samples from across the country for further study into the origin and spread of the virus.[58]

Media circuit upon return to US

Lipkin returned to the US around Feb 4, whereupon "I started going onto the news media and sharing as much as I could.” [59] As an expert in virology who had recently been to China, his opinion was highly valued. He noted: “You can push with CNN and NBC - but that’s not really where you need to push - you need to go onto Oz and talk to people who reach the entire country.” [60] To this end, he said, "I never turn down Fox - it’s an opportunity to preach in the wilderness."[61]

On the day of his return, the Columbia University website quoted Lipkin as saying: "So far, there is no evidence that the Wuhan virus will spread to the same extent as SARS, which reached 33 countries."[62] Though he cautioned that this was not the time to be complacent.

On the Feb 10 he told NBC that SARS-nCoV-2 is "not nearly as challenging for us as influenza."[63] while also predicting a "dramatic reduction" in cases by late Feb as weather warmed.[64] Making an appearance on the Doctor Oz show on March 12 before a studio audience, Lipkin, to allay people's concerns about the need for masks, said: "One of the things I try to emphasize whenever I talk about this virus is … we will almost certainly have additional fatalities ... but it is not as dangerous as some people may suggest - so if for example we look at this like seasonal flu - it’s gonna be much less than say 1% of people - that’s not to say that we won’t lose lives and it’s not important."[65]

Later, on March 28, when the virus had begun to explode in New York, Lipkin recalled: "When I came back from China ... and I tried to convey my concerns - you know people didn’t take it as seriously as they should have done."[66]

Chinese government transparency

With regard to China’s handling of the crisis, Lipkin said in an interview with TWIV: "They were transparent in sharing that this was a serious threat globally."[67] Lipkin added, "There’s going to be some stuff that’s going to come out that’s going to show more insight into the origins of the outbreak. Some people are going to say this is evidence that they (Chinese Communist Party officials) withheld information - I’m gonna push back and say 'No, that’s not the case.'[68] During his visit to China in late January, 2020, Lipkin offered his services to President Xi Jin-ping, "who I found very impressive."[69]

Chinese media reported that Lipkin "lauded China's transparent and professional approach". His visit was promoted as evidence that China was willing to cooperate with foreign scientists,[70] despite accusations by Wuhan doctors of a cover up.[71]

Lipkin infected with SARS-CoV-2

Starting around March 13–14, Lipkin said he had "a mild upper respiratory tract infection for about a week".[72] On Mar 20, his symptoms worsened, specifically, "a very painful headache that literally woke me from sleep... I had it for two, three days thereafter and some night sweats. That’s when ...I went in and had myself tested by one of our faculty members."

This time-frame indicates that the consultant for Contagion, was himself contagious around the time of his media appearances in a high community-contact environment. Lipkin noted from his investigative tour of China: "Anybody who has any sort of suspicious respiratory tract infection, they’re gonna be all over it with diagnostic tests ... and the ability to isolate and contain - which we don’t do."[73]

Instead, Lipkin continued travelling across New York conducting media interviews to spread his messaging. On March 18 he made his last pre-quarantined appearance on Dr. Oz, where he warned: "(This virus) will percolate below the surface - then suddenly it hits a community or an individual who’s very susceptible - and then it takes off like wildfire."[74]

Later whilst recovering, he remarked: "The irony is I went to China and everybody wears masks ... no problems. I come back ... I come out of confinement - I’m doing media - I’m travelling around the city - most of the time I’m very cautious - but when you start doing media it's very difficult - because you’ve got people ... doing make-up, doing hair, they’re putting microphones in front of you - there’s a lot of community contact."[75]

Treatment

Initially, Lipkin wanted to try plasma therapy: "My close friend, the Foreign Minister of Health of China ... Chen Zhu, was going to send me plasma from China - so i could get infused."[76] Plasma therapy involves transfusing the liquid portion of the blood from a recovered patient into an infected one.[77] According to Lipkin, Zhu said, "'Look, I'll send you some plasma!' I’m A+, he’s A positive ... he was also gonna send me some antibodies against (inaudible - timestamp 4:49 )."[78]

Lipkin said he was "very eager" to do it, but as it was an experimental treatment reserved for severe cases due to scarce supplies, "I was unable to get anybody to agree to allow me to be infused with this unknown plasma from China - it was just too difficult."[79]

The "Columbia IV people" also counseled Lipkin against it, saying, "we’ll just do the hydroxychloroquine".[80] A few days later Lipkin began to rally and "hiked about a mile and a half". However coming back home on a slight uphill gradient, Lipkin experienced "shortness of breath".[81]

As to whether hydroxychloroquine had aided his recovery, Lipkin said he had "no idea", but reported "800 mg certainly makes you feel light-headed."[82]

Proximal Origins paper

On March 17, 2020, a paper Lipkin co-authored, titled The proximal origins of SARS-CoV-2, was published in Nature Medicine.[83] The premise of the paper was that SARS-CoV-2 arose through a process of natural evolution and therefore had not leaked from a laboratory.

Wet market/pangolin theory

The paper proposed that horseshoe bats, possibly from Yunan, infected Malayan pangolin, which were smuggled into Guangdong, then transported to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, where they were slaughtered for sale. In the process, the bat virus mutated in pangolin until it became infectious to humans. Countering the notion that the virus may have leaked from a research facility, the authors write: "...pangolins...provide a much stronger and more parsimonious explanation" of how the virus originated through natural selection.[84]

This Wuhan wet market narrative, concurred with the initial explanation of Chinese authorities,[85][86] although a paper published on Jan 26 by Chinese researchers reported that 13 of the first 41 cases had no epidemiological link with the market, including the first known case.[87]

Regarding the mutations in pangolin, the Proximal Origin authors remarked: "For a precursor virus to acquire both the polybasic cleavage site and mutations in the spike protein suitable for binding to human ACE2, an animal host would probably have to have a high population density (to allow natural selection to proceed efficiently)."[88] (authors' brackets)

Although Wikipedia describes pangolin as "solitary animals, meeting only to mate", Proximal Origins inferred that the 'high-population density' threshold may have been met during transportation or at the market. A Nature article noted, "pangolins were not listed on an inventory of items sold at the market", but didn't dismiss the idea that they may have been sold there illegally.[89] As of June 2020, no evidence had emerged that pangolin were sold at the market.

On May 26, Chinese media reported that Gao Fu (George F. Gao), director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, had announced that, "no viruses were detected in the animal samples" collected from the Wuhan market in early January.[90] Lipkin referred to Gao Fu as a "close friend" who he consulted with on his investigative trip to China from Jan 29-Feb 4.

Natural origins

The Proximal Origins paper stated: "Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus" and presents "strong evidence" that SARS-nCoV-2 was the result of natural selection.[83] In an interview with India Today, Lipkin re-emphasized this point: "There is no evidence whatsoever that there was an effort to create anything of this sort. There is no evidence that there are animals in which it was passaged to create this problem."[91]

However, a 2008 paper published in Journal of Virology, titled Difference in Receptor Usage between SARS and SARS-Like Coronavirus of Bat Origin did detail a purposeful manipulation of an earlier bat virus (SL-CoV S) sample they'd collected. A 'gain-of-function' experiment was performed to make the virus more infectious to humans. They wrote: "A series of S chimeras was constructed by inserting different sequences of the SARS-CoV S into the SL-CoV S backbone." In terms of Ace2-binding, or enhancing the ability of the virus to infect human cells, the experiment was successful: "ACE2-binding activity of SL-CoVs was easily acquired by the replacement of a relatively small sequence segment of the S protein from the SARS-CoV S sequence." The paper concluded: "It remains to be seen whether a recombinant SL-CoV containing a CS protein (e.g., CS14-608) will be capable of infecting experimental animals and causing disease."[92] Four of the co-authors of this paper were researchers from Wuhan Institute of Virology, two were from CSRIO, Australia. An additional paper from WIV scientists and Peter Daszak in 2016 detailed "the construction of WIV1 (a bat virus) mutants."[93] According to a co-author of Proximal origins, Edward C. Holmes, the closest known virus was RaTG13 (96.2% identical) which was held at WIV.[94]

Lipkin maintained that the types of changes observed in SARS-CoV-2 that differentiate it from RaTG13 (held at WIV) "would not have occurred... unless it was being passed somehow either in animals or in people" and that "if it had been modified in the Wuhan Institute of Virology, they would have used a different sequence for that purpose because this was not obvious." As such, Lipkin lamented that “rumors have their own life - I don’t know how they’re sustained but they seem to be sustained - there doesn’t seem to be any good way to choke them."[95]

Reaction

Lipkin’s paper was widely cited by media outlets as evidence debunking growing "conspiracy theories" that the virus may have accidentally escaped from an Wuhan lab.[96][97][98] In China, the Global Times said, "US scientists, such as the world's leading "virus hunter" W. Ian Lipkin, have been sticking to the facts and insisting on scientific integrity when it comes to research and cooperation with China."[99] The China Daily praised Lipkin as an "intellectual giant" who had "shared profound insights and lessons".[100] A spokesperson for the Chinese Consulate General in Sydney referenced Proximal Origins and WHO experts, saying "the novel coronavirus originated through natural processes and was not manipulated or produced in a laboratory." It noted: "The scientific community has ...reported that the virus is possibly related to bats and pangolins."[101]

Other international experts also agreed with Lipkin's analysis. Maureen Miller, an epidemiologist who had cooperated with WIV researchers, said the idea the virus may have escaped from a lab was an “absolute conspiracy theory”,[102] while disease ecologist Peter Daszak, who had also collaborated with WIV, branded any accidental escape scenario as "pure baloney".[103] WHO emergencies chief Michael J. Ryan said WHO had "listened again and again to numerous scientists" and "(w)e are assured that this virus is natural in origin."[104] Researchers from Duke University, which operates a joint research institute with Wuhan University,[105] also agreed with the Proximal Origins' pangolin premise, stating that "SARS-CoV-2 appears to be a hybrid between bat and pangolin viruses."[106]

In addition, a petition, with links to Proximal Origins was circulated through the scientific community. It stated: “The rapid, open, and transparent sharing of data (by China) on this outbreak is now being threatened by rumours and misinformation around its origins. We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin. We support the call from the Director-General of WHO to promote scientific evidence and unity over misinformation and conjecture.”[107]

There was some dissent, however. Professor Richard Ebright of Rutgers University’s Waksman Institute of Microbiology, said the paper provided "no basis to rule out a lab accident" and was itself just conjecture. Ebright pointed out that bat viruses collected by WIV researchers were also studied at the less secure Wuhan Center for Disease Control, a BSL-2 facility, "which provides only minimal protections against infection of lab workers". He cautioned that “Virus collection, culture, isolation, or animal infection at BSL-2 with a virus having the transmission characteristics of the outbreak virus, would pose substantial risk of infection of a lab worker, and from the lab worker, the public.”[108]

Gain-of-function research

Gain-of-function (GoF) experiments aim to increase the virulence and/or transmissibility of viruses.[109] This includes targeted genetic modification (to create hybrid viruses), the serial passaging of a virus through a host animal (to generate adaptive mutations), and targeted mutagenesis (to introduce mutations).[110] Lipkin is a listed “supporter” of GoF advocate group, Scientists for Science,[111] which was co-founded by Columbia colleague Vincent Racaniello.[112] Lipkin is also a board member of EcoHealth Alliance, headed by Peter Dszak, with whom Lipkin co-wrote papers on MERS and techniques for preventing pandemics.[113][114][115][116][117] EcoHealth scientists, including Daszak, also collaborated with those from Wuhan Institute of Virology where GoF experiments on bat viruses are performed,[118][119][120] until funding was withdrawn in May 2020.[121] Shi Zheng-li from WIV, was part of the team in 2008 that inserted a SARS sequence into a non-infectious bat virus backbone (SL-CoVs) to make it infectious. They wrote such research was “invaluable in formulating control strategies for potential future outbreaks.”[122] In December, 2015, Lipkin visited WIV where he shared insights on "the evolution of techniques and tactics on pathogen discovery and demonstrated the current progress of molecular biotechnologies."[120] GoF research was banned in the US under the Obama administration in October 2014.[123]

Lipkin’s views

Lipkin, while not endorsing every GoF experiment, said: “There clearly are going to be instances where gain-of-function research is necessary and appropriate.” He gave the example of Ebola, which is incapable of airborne transfer, but “researchers could make a case for the need to determine how the virus could evolve in nature by engineering a more dangerous version in the lab."[124]

Regarding the security level of labs in which work on dangerous pathogens can be performed, Lipkin noted, "(w)ork is more expensive and less efficient when pursued at biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) than at BSL-3 or... BSL-3-Ag (agriculture).” Whereas BSL-4 requires facilities to be inspected daily, personnel to be monitored for symptoms of disease, and virus samples, equipment, and personnel to be logged in and out, Lipkin noted: "These measures are not required at BSL-3".[125] He said BSL-3 labs (such as the ones at Columbia and Sun Yat-sen University,[126] with which Lipkin and Columbia collaborate[127]), should be allowed to conduct GoP work on globally active viruses in order to expedite research for a vaccine, though he added "there should be some sort of guidelines”.[128]

To illustrate his stance, Lipkin referenced Contagion, where the maverick scientist (played by Elliot Gould), conflicts with health authorities, a story which was “loosely based on my experiences during the West Nile Virus outbreak in 1999.” In the movie, the researcher is told to “cook his samples” and that all research is to be moved to the BSL-4 lab due to security concerns, but he “ultimately find(s) a way to grow the virus and make a vaccine” and save the world. In real life, Lipkin recounted: “Although our team identified the causative agent (WNV), political wrangling delayed permitting and shipment of the virus to our laboratory. To expedite diagnostics and drug development, I decided to recover the virus by transfecting genomic viral RNA.”[128] Unlike the movie, no effective vaccine for humans was found for West Nile Virus,[129] or SARS or any coronaviruses, as a result of GoF research.[130]

Criticism of GoF

Ian Mackay (University of Queensland, Australia), said: “One cannot legislate for every accident or human error; all manner of things can go wrong, and if an outbreak spreads to the community the consequences could be horrendous.”[123] Marc Lipsitch (Harvard University, MA, USA) argued that GoF research is dangerous and unnecessary, saying that deliberate mutations of viruses have not produced novel insights.“There is nothing for the purposes of surveillance that we did not already know. Enhancing potential pandemic pathogens in this manner is simply not worth the risk.”[123] According to a Lancet article, the moratorium on GoP was prompted by a slew of accidents in the US at BSL facilities in 2014: "The news that dozens of workers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) might have been exposed to anthrax, that vials of smallpox virus had been left lying around in an NIH storeroom, and that the CDC had unwittingly sent out samples of ordinary influenza virus contaminated with H5N1, shook faith in the country's biosafety procedures."[123] Funding for GoP research in the US resumed in 2017.[131]

Selected awards and honors

| Year(s) | Award/Honor | Institution/Organization |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | PRC 70th Anniversary Medal[132] | Chinese Central Government, Central Military Commission, and State Council |

| 2016 | China International Science and Technology Cooperation Award[133] | People's Republic of China |

| 2015 | Fellow[134] | Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) |

| 2010 | Member[135] | Association of American Physicians (AAP) |

| 2008 | John Snow Professor of Epidemiology[134] | Columbia University |

| 2006 | Fellow[135] | American Society for Microbiology (ASM) |

| 2004 | Fellow[135] | New York Academy of Sciences |

| 2003 | Special Advisor to the Ministry of Science and Technology[136] | People's Republic of China |

| 1986-87 | President, Society of Fellows[137] | Scripps Research Institute |

References

- "Ian Lipkin The Virus Hunter" (PDF). Discover. April 2012.

- Zimmer, Carl (November 22, 2010). "A Man From Whom Viruses Can't Hide". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- Kim, Elizabeth (February 3, 2020). "NYC Team Led By Scientist Who Advised On "Contagion" Is Racing To Unlock The Coronavirus. Here's What They Told Us". Gothamist. New York Public Radio. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- This Week in Virology (TWiV) podcast.28 March 2020 http://www.microbe.tv/twiv/twiv-special-lipkin/

- Gewertz, Catherine (March 31, 1993). "Realtor to Give $1.62 Million for UCI Chair". Los Angeles Times.

- "Centers of Excellence for Translational Research". nih.gov.

- "Region II NIH Regional Center of Excellence in Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases".

- "Dr. W. Ian Lipkin Named Co-Chair of CDC Subcommittee". 15 July 2010.

- "Homeland Security Presidential Directive". archives.gov. 18 October 2007.

- "Home - EcoHealth Alliance". ecohealthalliance.org.

- "Five Questions for Ian Lipkin, the Scientist Who Designed Contagion's Virus". 9 September 2011.

- Lipkin, W. I (April 1979). "Eosinophil Counts in Bacteremia" (PDF). Archives of Internal Medicine. 139 (4): 490–1. doi:10.1001/archinte.1979.03630410094035. PMID 435009.

- Hamblin, Terry (1998). "Plasmapheresis". Encyclopedia of Immunology. pp. 1969–1971. doi:10.1006/rwei.1999.0495. ISBN 9780122267659.

- Zimmer, Carl (November 22, 2010). "A Man From Whom Viruses Can't Hide". New York Times.

- Landay, A; Poon, M. C; Abo, T; Stagno, S; Lurie, A; Cooper, M. D (1983). "Immunologic studies in asymptomatic hemophilia patients. Relationship to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 71 (5): 1500–4. doi:10.1172/JCI110904. PMC 437015. PMID 6222070.

- Lipkin, W. I; Parry, G; Kiprov, D; Abrams, D (1985). "Inflammatory neuropathy in homosexual men with lymphadenopathy" (PDF). Neurology. 35 (10): 1479–83. doi:10.1212/WNL.35.10.1479. PMID 2993951.

- Lipkin, W. I; Travis, G. H; Carbone, K. M; Wilson, M. C (1990). "Isolation and characterization of Borna disease agent cDNA clones". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (11): 4184–8. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4184L. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.11.4184. JSTOR 2354914. PMC 54072. PMID 1693432.

- Lipkin, W. I (2010). "Microbe hunting". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 74 (3): 363–77. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00007-10. PMC 2937520. PMID 20805403.

- "Columbia University Center for Infection and Immunity Publications, 1990-99".

- Lipkin, W. I; Carbone, K. M; Wilson, M. C; Duchala, C. S; Narayan, O; Oldstone, M. B (1988). "Neurotransmitter abnormalities in Borna disease". Brain Research. 475 (2): 366–70. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(88)90627-0. PMID 2905625.

- Briese, T; Schneemann, A; Lewis, A. J; Park, Y. S; Kim, S; Ludwig, H; Lipkin, W. I (1994). "Genomic organization of Borna disease virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (10): 4362–6. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.4362B. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.10.4362. PMC 43785. PMID 8183914.

- Bode, L; Ludwig, H (2003). "Borna Disease Virus Infection, a Human Mental-Health Risk". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (3): 534–545. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.3.534-545.2003. PMC 164222. PMID 12857781.

- Lipkin, W. I; Hornig, M; Briese, T (2001). "Borna disease virus and neuropsychiatric disease--a reappraisal". Trends in Microbiology. 9 (7): 295–8. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02071-6. PMID 11435078.

- Hornig, M; Briese, T; Licinio, J; Khabbaz, R. F; Altshuler, L. L; Potkin, S. G; Schwemmle, M; Siemetzki, U; Mintz, J; Honkavuori, K; Kraemer, H. C; Egan, M. F; Whybrow, P. C; Bunney, W. E; Lipkin, W. I (2012). "Absence of evidence for bornavirus infection in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 17 (5): 486–93. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.179. PMC 3622588. PMID 22290118.

- "Does Borna Disease Virus Cause Mental Health? Stephanie Berger. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. January 31, 2012".

- Briese, T; Jia, X. Y; Huang, C; Grady, L. J; Lipkin, W. I (1999). "Identification of a Kunjin/West Nile-like flavivirus in brains of patients with New York encephalitis". Lancet. 354 (9186): 1261–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04576-6. PMID 10520637.

- Qiao, M; Ashok, M; Bernard, K. A; Palacios, G; Zhou, Z. H; Lipkin, W. I; Liang, T. J (2004). "Induction of sterilizing immunity against West Nile Virus (WNV), by immunization with WNV-like particles produced in insect cells". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 190 (12): 2104–8. doi:10.1086/425933. PMID 15551208.

- "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: West Nile Virus". 3 June 2020.

- Lipkin, W. Ian (2009). "SARS: How a global epidemic was stopped". Global Public Health. 4 (5): 500–501. doi:10.1080/17441690903061389.

- "Ian Lipkin Receives Top Science Honor in China, Columbia University, January 8, 2016".

- Zhai, J; Briese, T; Dai, E; Wang, X; Pang, X; Du, Z; Liu, H; Wang, J; Wang, H; Guo, Z; Chen, Z; Jiang, L; Zhou, D; Han, Y; Jabado, O; Palacios, G; Lipkin, W. I; Tang, R (2004). "Real-time polymerase chain reaction for detecting SARS coronavirus, Beijing, 2003". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (2): 300–3. doi:10.3201/eid1002.030799. PMC 3322935. PMID 15030701.

- "Columbia University Technology Ventures, submission date April 15, 2003".

- "W. Ian Lipkin, MD, Bio, Center for Infection and Immunity".

- "Grant: Risk of Viral Emergence from Bats, funding period 2008-13".

- Quan, P. L; Firth, C; Street, C; Henriquez, J. A; Petrosov, A; Tashmukhamedova, A; Hutchison, S. K; Egholm, M; Osinubi, M. O; Niezgoda, M; Ogunkoya, A. B; Briese, T; Rupprecht, C. E; Lipkin, W. I (2010). "Identification of a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in a leaf-nosed bat in Nigeria". mBio. 1 (4). doi:10.1128/mBio.00208-10. PMC 2975989. PMID 21063474.

- "Back on SARS standby". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2020-06-12. Check date values in:

|archive-date=(help) - "Bat Out of Hell? Egyptian Tomb Bat May Harbor MERS Virus". 22 August 2013.

- "Meet the World's Top Virus Hunter".

- Anthony, S. J; Ojeda-Flores, R; Rico-Chávez, O; Navarrete-Macias, I; Zambrana-Torrelio, C. M; Rostal, M. K; Epstein, J. H; Tipps, T; Liang, E; Sanchez-Leon, M; Sotomayor-Bonilla, J; Aguirre, A. A; Ávila-Flores, R; Medellín, R. A; Goldstein, T; Suzán, G; Daszak, P; Lipkin, W. I (2013). "Coronaviruses in bats from Mexico". The Journal of General Virology. 94 (Pt 5): 1028–1038. doi:10.1099/vir.0.049759-0. PMC 3709589. PMID 23364191.

- "Will MERS become a global threat?".

- Memish, Z. A; Mishra, N; Olival, K. J; Fagbo, S. F; Kapoor, V; Epstein, J. H; Alhakeem, R; Durosinloun, A; Al Asmari, M; Islam, A; Kapoor, A; Briese, T; Daszak, P; Al Rabeeah, A. A; Lipkin, W. I (2013). "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bats, Saudi Arabia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 19 (11): 1819–23. doi:10.3201/eid1911.131172. PMC 3837665. PMID 24206838.

- Anthony, S. J; Gilardi, K; Menachery, V. D; Goldstein, T; Ssebide, B; Mbabazi, R; Navarrete-Macias, I; Liang, E; Wells, H; Hicks, A; Petrosov, A; Byarugaba, D. K; Debbink, K; Dinnon, K. H; Scobey, T; Randell, S. H; Yount, B. L; Cranfield, M; Johnson, C. K; Baric, R. S; Lipkin, W. I; Mazet, J. A (2017). "Further Evidence for Bats as the Evolutionary Source of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus". mBio. 8 (2). doi:10.1128/mBio.00373-17. PMC 5380844. PMID 28377531.

- "MERS-like coronavirus identified in Ugandan bat".

- "NIH Awards $9.6 Million Grant to Columbia for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Collaborative Research Center".

- "CfS for ME/CFS: Who We Are".

- "NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools, Project Information".

- "NIH announces center for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome research".

- Mishra, N; Ng, TFF; Marine, RL; Jain, K; Ng, J; Thakkar, R; Caciula, A; Price, A; Garcia, JA; Burns, JC; Thakur, KT; Hetzler, KL; Routh, JA; Konopka-Anstadt, JL; Nix, WA; Tokarz, R; Briese, T; Oberste, MS; Lipkin, WI (13 August 2019). "Antibodies to Enteroviruses in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Acute Flaccid Myelitis". mBio. 10 (4): e01903-19. doi:10.1128/mBio.01903-19. PMC 6692520. PMID 31409689.

- "Hear Firsthand From the Doctor Who is Getting Closer to Finding a Cure for AFM". The Dr. Oz Show. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "How Researchers Figured Out What Causes AFM". The Dr. Oz Show. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Schubert, RD; Hawes, IA; Ramachandran, PS; Ramesh, A; Crawford, ED; Pak, JE; Wu, W; Cheung, CK; O'Donovan, BD; Tato, CM; Lyden, A; Tan, M; Sit, R; Sowa, GA; Sample, HA; Zorn, KC; Banerji, D; Khan, LM; Bove, R; Hauser, SL; Gelfand, AA; Johnson-Kerner, BL; Nash, K; Krishnamoorthy, KS; Chitnis, T; Ding, JZ; McMillan, HJ; Chiu, CY; Briggs, B; Glaser, CA; Yen, C; Chu, V; Wadford, DA; Dominguez, SR; Ng, TFF; Marine, RL; Lopez, AS; Nix, WA; Soldatos, A; Gorman, MP; Benson, L; Messacar, K; Konopka-Anstadt, JL; Oberste, MS; DeRisi, JL; Wilson, MR (21 October 2019). "Pan-viral serology implicates enteroviruses in acute flaccid myelitis". Nature Medicine. 25 (11): 1748–1752. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0613-1. PMC 6858576. PMID 31636453.

- "Virus could be the cause of mysterious polio-like illness AFM, study says". CNN Health. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "What Causes a Mysterious Paralysis in Children? Researchers Find Viral Clues". The New York Times. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Evidence links poliolike disease in children to a common type of virus". Science Magazine. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Andersen, Kristian G.; Rambaut, Andrew; Lipkin, W. Ian (March 17, 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature.com. Springer Nature Limited. PMID 32284615. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "An Update on Ian Lipkin". Mailman School of Public Health. Columbia University. March 25, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- Weintraub, Karen (12 February 2020). "Epidemiologist Veteran of SARS and MERS Shares Coronavirus Insights after China Trip". Scientific American. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Manson, Katrina; Yu, Sun (27 April 2020). "US and Chinese researchers team up for hunt into Covid origins". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Microbe TV, This Week in Virology, Lipkin podcast interview, timestamp 19:30, Mar 28, 2020/

- Microbe TV, This Week in Virology, Lipkin podcast interview, timestamp 19:35, Mar 28, 2020/

- New Yorker, A local guide to the coronavirus, Mar 9, 2020

- Coumbia, Public Health, Our experts respond to coronavirus outbreak, Feb 4, 2020

- CNBC: Ian Lipkin, scientists worry that coronavirus could become worse than the flu, Feb 10, 2020

- "Coronavirus spread may 'dramatically slow' disease expert hopes". Evening Standard. 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Doctor Oz Show: Interview with Ian Lipkin, timestamp 4:00, Mar 12, 2020

- "TWiV Special: Conversation with a COVID-19 patient, Ian Lipkin | This Week in Virology, timestamp 13:07". Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Doctor Oz Show: Interview with Ian Lipkin, timestamp 19:05, Mar 12, 2020

- Microbe TV, This Week in Virology, Lipkin podcast interview, timestamp 28:30, Mar 28, 2020/

- timestamp 41:46 "Dr Ian Lipkin dismisses China lab theory, says virus came from bats not lab" Check

|url=value (help). India Today. Retrieved 2020-06-11. - Global Times: Renowned epidemiologist Walter Lipkin lauds China's transparent and professional approach against coronavirus outbreak, Feb 3, 2020

- Washington Post, Early missteps and state secrecy in China probably allowed the coronavirus to spread farther and faster, Feb 2, 2020

- Microbe TV, This Week in Virology, Lipkin podcast interview, timestamp 02:00, Mar 28, 2020/

- Microbe TV, This Week in Virology, Lipkin podcast interview, timestamp 23:00, Mar 28, 2020/

- Dr. Oz: Interview with Ian Lipkin: The critical guide to recognizing the first symptoms of coronavirus

- Microbe TV, This Week in Virology, Lipkin podcast interview, timestamp 07:21, Mar 28, 2020/

- "Dr Ian Lipkin dismisses China lab theory, says virus came from bats not lab, time stamp 10.58". India Today. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- "Convalescent plasma therapy - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- "TWiV Special: Conversation with a COVID-19 patient, Ian Lipkin | This Week in Virology, timestamp 4.30". Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- "Dr Ian Lipkin dismisses China lab theory, says virus came from bats not lab, timestamp 10:58". India Today. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "TWiV Special: Conversation with a COVID-19 patient, Ian Lipkin | This Week in Virology, timestamp 4.30". Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "TWiV Special: Conversation with a COVID-19 patient, Ian Lipkin | This Week in Virology, timestamp 8:00". Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "TWiV Special: Conversation with a COVID-19 patient, Ian Lipkin | This Week in Virology, timestamp 04:40". Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Andersen, Kristian G.; Rambaut, Andrew; Lipkin, W. Ian; Holmes, Edward C.; Garry, Robert F. (April 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. ISSN 1546-170X. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- Andersen, Kristian G.; Rambaut, Andrew; Lipkin, W. Ian; Holmes, Edward C.; Garry, Robert F. (April 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. ISSN 1546-170X.

- "Columbia News, What you need to know about a new virus outbreak, Jan 24,2020".

- Gan, Nectar. "The Wuhan lab at the center of the US-China blame game: What we know and what we don't". CNN. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Cohen, Jon (2020-01-26). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Andersen, Kristian G.; Rambaut, Andrew; Lipkin, W. Ian; Holmes, Edward C.; Garry, Robert F. (Mar 17). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. ISSN 1546-170X. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Cyranoski, David (2020-02-07). "Did pangolins spread the China coronavirus to people?". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00364-2.

- "Wuhan's Huanan seafood market a victim of COVID-19: CDC director - Global Times". www.globaltimes.cn. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Dr Ian Lipkin dismisses China lab theory, says virus came from bats not lab, timestamp 30:30". India Today. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Ren, Wuze; Qu, Xiuxia; Li, Wendong; Han, Zhenggang; Yu, Meng; Zhou, Peng; Zhang, Shu-Yi; Wang, Lin-Fa; Deng, Hongkui; Shi, Zhengli (2008-02-15). "Difference in Receptor Usage between Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Coronavirus and SARS-Like Coronavirus of Bat Origin". Journal of Virology. 82 (4): 1899–1907. doi:10.1128/JVI.01085-07. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 2258702. PMID 18077725.

- Zeng, Lei-Ping; Gao, Yu-Tao; Ge, Xing-Yi; Zhang, Qian; Peng, Cheng; Yang, Xing-Lou; Tan, Bing; Chen, Jing; Chmura, Aleksei A.; Daszak, Peter; Shi, Zheng-Li (2016-07-15). "Bat Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Like Coronavirus WIV1 Encodes an Extra Accessory Protein, ORFX, Involved in Modulation of the Host Immune Response". Journal of Virology. 90 (14): 6573–6582. doi:10.1128/JVI.03079-15. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 4936131. PMID 27170748.

- Weinland, Don; Manson, Katrina (2020-05-05). "How a Wuhan lab became embroiled in a global coronavirus blame game | Free to read". www.ft.com. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- "TWiV Special: Conversation with a COVID-19 patient, Ian Lipkin | This Week in Virology, timestamp 27:00". Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Spinney, Laura (2020-03-28). "Is factory farming to blame for coronavirus?". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Mannix, Liam (2020-04-24). "Scientists dispel theory COVID-19 escaped from lab". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "No, the coronavirus wasn't made in a lab. A genetic analysis shows it's from nature". Science News. 2020-03-26. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Scientific spirit needed amid major crisis - Global Times". www.globaltimes.cn. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- 董志成. "Three themes to meditate on during the pause of pandemic - Chinadaily.com.cn". epaper.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Spokesperson of the Chinese Consulate General in Sydney Responding to a Question about the so-called "Wuhan Lab--Coronavirus Leak Theory"". sydney.chineseconsulate.org. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- "Where did Covid-19 come from? What we know about its origins". the Guardian. 2020-05-01. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- "Spokesperson of the Chinese Consulate General in Sydney Responding to a Question about the so-called "Wuhan Lab--Coronavirus Leak Theory"". sydney.chineseconsulate.org. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- "WHO says virus 'natural in origin'". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- "Overview | Duke Kunshan University". dukekunshan.edu.cn. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- "Evolution of pandemic coronavirus outlines path from animals to humans: The virus's ability to change makes it likely that new human coronaviruses will arise". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- Calisher, Charles; Carroll, Dennis; Colwell, Rita; Corley, Ronald B.; Daszak, Peter; Drosten, Christian; Enjuanes, Luis; Farrar, Jeremy; Field, Hume; Golding, Josie; Gorbalenya, Alexander (2020-03-07). "Statement in support of the scientists, public health professionals, and medical professionals of China combatting COVID-19". The Lancet. 395 (10226): e42–e43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30418-9. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159294. PMID 32087122.

- "Experts know the new coronavirus is not a bioweapon. They disagree on whether it could have leaked from a research lab". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Selgelid, Michael J. (2016). "Gain-of-Function Research: Ethical Analysis". Science and Engineering Ethics. 22 (4): 923–964. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9810-1. ISSN 1353-3452. PMC 4996883. PMID 27502512.

- "Gryphon Report, Final Draft, Analysis of Gain-of-Function Research, Dec, 2015, p43-45" (PDF).

- "Scientists for Science". www.scientistsforscience.org. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- Jul 30, Robert Roos | News Editor | CIDRAP News |; 2014. "Scientists voice support for research on dangerous pathogens". CIDRAP. Retrieved 2020-06-10.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Alagaili, Abdulaziz N.; Briese, Thomas; Mishra, Nischay; Kapoor, Vishal; Sameroff, Stephen C.; Wit, Emmie de; Munster, Vincent J.; Hensley, Lisa E.; Zalmout, Iyad S.; Kapoor, Amit; Epstein, Jonathan H. (2014-05-01). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection in Dromedary Camels in Saudi Arabia". mBio. 5 (2). doi:10.1128/mBio.00884-14. ISSN 2150-7511. PMID 24570370.

- Briese, Thomas; Mishra, Nischay; Jain, Komal; Zalmout, Iyad S.; Jabado, Omar J.; Karesh, William B.; Daszak, Peter; Mohammed, Osama B.; Alagaili, Abdulaziz N.; Lipkin, W. Ian (2014-07-01). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Quasispecies That Include Homologues of Human Isolates Revealed through Whole-Genome Analysis and Virus Cultured from Dromedary Camels in Saudi Arabia". mBio. 5 (3). doi:10.1128/mBio.01146-14. ISSN 2150-7511. PMID 24781747.

- Morse, Stephen S.; Mazet, Jonna AK; Woolhouse, Mark; Parrish, Colin R.; Carroll, Dennis; Karesh, William B.; Zambrana-Torrelio, Carlos; Lipkin, W. Ian; Daszak, Peter (2012-12-01). "Prediction and prevention of the next pandemic zoonosis". The Lancet. 380 (9857): 1956–1965. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61684-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 3712877. PMID 23200504.

- Alagaili, Abdulaziz N.; Briese, Thomas; Karesh, William B.; Daszak, Peter; Lipkin, W. Ian (2014-08-29). "Reply to "Concerns About Misinterpretation of Recent Scientific Data Implicating Dromedary Camels in Epidemiology of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)"". mBio. 5 (4). doi:10.1128/mBio.01482-14. ISSN 2150-7511. PMID 25006235.

- Daszak, Peter; Lipkin, W Ian (December 2011). "The search for meaning in virus discovery". Current Opinion in Virology. 1 (6): 620–623. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.010. ISSN 1879-6257. PMC 4310690. PMID 22440920.

- Zeng, Lei-Ping; Gao, Yu-Tao; Ge, Xing-Yi; Zhang, Qian; Peng, Cheng; Yang, Xing-Lou; Tan, Bing; Chen, Jing; Chmura, Aleksei A.; Daszak, Peter; Shi, Zheng-Li (2016-06-24). "Bat Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Like Coronavirus WIV1 Encodes an Extra Accessory Protein, ORFX, Involved in Modulation of the Host Immune Response". Journal of Virology. 90 (14): 6573–6582. doi:10.1128/JVI.03079-15. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 4936131. PMID 27170748.

- "New Sars-like Coronavirus Discovered in Chinese Horseshoe Bats". EcoHealth Alliance. 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- "Professor Walter Ian Lipkin was invited by "Master Ge Hong Colloquium" of WIV to give a report----Wuhan Institute of Virology". english.whiov.cas.cn. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- Brewster, Jack. "U.S. Group That Works With Chinese On Infectious Disease Research Had Federal Grant Revoked". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Ren, Wuze; Qu, Xiuxia; Li, Wendong; Han, Zhenggang; Yu, Meng; Zhou, Peng; Zhang, Shu-Yi; Wang, Lin-Fa; Deng, Hongkui; Shi, Zhengli (2008-02-15). "Difference in Receptor Usage between Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Coronavirus and SARS-Like Coronavirus of Bat Origin". Journal of Virology. 82 (4): 1899–1907. doi:10.1128/JVI.01085-07. ISSN 0022-538X. PMID 18077725.

- Burki, Talha (2018-02-01). "Ban on gain-of-function studies ends". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 18 (2): 148–149. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30006-9. ISSN 1473-3099. PMC 7128689. PMID 29412966.

- magazine, Sara Reardon,Nature. "U.S. Suspends Risky Disease Research". Scientific American. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- "Dr. Ian Lipkin Addresses Concerns About H5N1 Research | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- "Sun Yat-sen University -- Zhongshan School of Medicine中山医学院". www.at0086.com. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- "China Honors Ian Lipkin | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- Lipkin, W. Ian (2012-11-01). "Biocontainment in Gain-of-Function Infectious Disease Research". mBio. 3 (5). doi:10.1128/mBio.00290-12. ISSN 2150-7511. PMID 23047747.

- "West Nile virus". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- "Why we might not get a coronavirus vaccine". the Guardian. 2020-05-22. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- "NIH Lifts Funding Pause on Gain-of-Function Research". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2017-12-18. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, China honors Lipkin, Jan 7, 2020

- Columbia Mailman School of Public Health: Ian Lipkin receives top science honor in China, Jan 8, 2016

- "W. Ian Lipkin Faculty Profile, Columbia University, MSPH".

- National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering; Affairs, Policy Global; Committee On Science, Technology; Management, Committee on Dual Use Research of Concern: Options for Future (2017-09-01). Dual Use Research of Concern in the Life Sciences: Current Issues and Controversies. p. 87. ISBN 9780309458917.

- "mBio Professional Profile: Board of Editors, W. Ian Lipkin, MD".

- "Science History Institute, Center for Oral History: W. Ian Lipkin, MD".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to W. Ian Lipkin. |