Workplace hazard controls for COVID-19

Hazard controls for COVID-19 in US workplaces are the application of occupational safety and health methodologies for hazard controls to the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The proper hazard controls in the workplace depend on the worksite and job task, based on a risk assessment of sources of exposure, disease severity in the community, and risk factors of individual workers who may be vulnerable to contracting COVID-19.

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

International response |

|

Medical response |

|

|

|

According to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), lower exposure risk jobs have minimal occupational contact with the public and other coworkers, for which basic infection prevention measures are recommended, including hand washing, encouraging workers to stay home if they are sick, respiratory etiquette, and maintaining routine cleaning and disinfecting of the work environment.

Medium exposure risk jobs include those that require frequent or close contact with people who are not known or suspected with COVID-19, but may be infected due to ongoing community transmission or international travel. This includes workers who have contact with the general public such as in schools, high-population-density work environments, and some high-volume retail settings. Hazard controls for this group, in addition to basic infection prevention measures, include ventilation using high-efficiency air filters, sneeze guards, and having personal protective equipment available in case a person with COVID-19 is encountered.

OSHA considers healthcare and mortuary workers exposed to known or suspected person with COVID-19 to be at high exposure risk, which increases to very high exposure risk if workers perform aerosol-generating procedures on, or collect or handle specimens from, known or suspected person with COVID-19. Hazard controls appropriate for these workers include engineering controls such as negative pressure ventilation rooms, and personal protective equipment appropriate to the job task.

Planning and risk assessment

COVID-19 outbreaks can have several effects within the workplace. Workers may be absent from work due to becoming sick, needing to care for others, or from fear of possible exposure. Patterns of commerce may change, both in terms of what goods are demanded, and the means of acquiring these goods (such as shopping at off-peak hours or through delivery or drive-through services). Lastly, shipments of items from geographic areas severely affected by COVID-19 may be interrupted.[1]:6

An infectious disease preparedness and response plan can be used to guide protective actions. Such plans address the levels of risk associated with various worksites and job tasks, including sources of exposure, risk factors arising from home and community settings, and risk factors of individual workers such as old age or chronic medical conditions. They also outline controls necessary to address those risks, and contingency plans for situations that may arise as a result of outbreaks. Infectious disease preparedness and response plans may be subject to national or subnational recommendations.[1]:7–8 Objectives for response to an outbreak include reducing transmission among staff, protecting people who are at higher risk for adverse health complications, maintaining business operations, and minimizing adverse effects on other entities in their supply chains. The disease severity in the community where the business is located affects the responses taken.[2]

Hazard controls

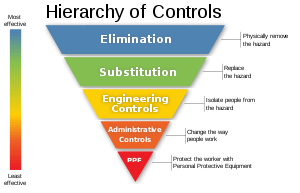

The hierarchy of hazard controls is a framework widely used in occupational safety and health to group hazard controls by effectiveness. Where COVID-19 hazards cannot be eliminated, the most effective controls are engineering controls, followed by administrative controls, and lastly personal protective equipment. Engineering controls involve isolating employees from work-related hazards without relying on worker behavior, and can be the most cost-effective solution to implement. Administrative controls are changes in work policy or procedures that require action by the worker or employer. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is considered less effective than engineering and administrative controls, but can help prevent some exposures. All types of PPE must be selected based upon the hazard to the worker, properly fitted as applicable (e.g., respirators), consistently and properly worn, regularly inspected, maintained, and replaced, as necessary, and properly removed, cleaned, and stored or disposed of to avoid contamination.[1]:12–16 Randomized controlled trials and simulation studies are needed to determine the most effective types of PPE for preventing the transmission of infectious diseases to healthcare workers. There is low quality evidence that supports making improvements or modifications to personal protective equipment in order to help decrease contamination. Examples of modifications include adding tabs to masks or gloves to ease removal and designing protective gowns so that gloves are removed at the same time. In addition, there is weak evidence that the following PPE approaches or techniques may lead to reduced contamination and improved compliance with PPE protocols: Wearing double gloves, following specific doffing (removal) procedures such as those from the CDC, and providing people with spoken instructions while removing PPE.[4]

All workplaces

Often workplaces are settings where groups share many hours of the day indoors. These are conditions that can facilitate the transmission of disease,[5] but also control it through workplace practices and policies.[6] Identifying industries or particular jobs that have the highest potential exposure to a specific risk can help in the development of interventions to control or prevent the spread of diseases such as COVID-19.[7][8][9]

According to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), lower exposure risk jobs have minimal occupational contact with the public and other coworkers.[1]:18–20 Basic infection prevention measures recommended for all workplaces include frequent and thorough hand washing, encouraging workers to stay home if they are sick, respiratory etiquette including covering coughs and sneezes, providing tissues and trash receptacles, preparing for telecommuting or staggered shifts if needed, discouraging workers from using others' tools and equipment, and maintaining routine cleaning and disinfecting of the work environment. Prompt identification and isolation of potentially infectious individuals is a critical step in protecting workers, customers, visitors, and others at a worksite.[1]:8–9 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that employees who have symptoms of acute respiratory illness are to stay home until they are free of fever, signs of a fever, and any other symptoms for at least 24 hours without the use of fever-reducing or other symptom-altering medicines, and that sick leave policies are flexible, permit employees to stay home to care for a sick family member, and that employees are aware of these policies.[2]

There are also psychosocial hazards arising from anxiety or stress from worries about contracting COVID-19, the illness or death of a relative or friend, changes in work patterns, and financial or interpersonal difficulties arising from the pandemic. Social distancing measures may prevent typical coping mechanisms such as personal space or sharing problems with others. Controls for these hazards include managers checking on workers to ask how they are, facilitating worker interactions, and formal services for employee assistance, coaching, or occupational health.[10]

Medium-risk workplaces

According to OSHA, medium exposure risk jobs include those that require frequent or close contact within six feet (1.8 m) of people who are not known or suspected COVID-19 patients, but may be infected with SARS-CoV-2 due to ongoing community transmission around the business location, or because the individual has recent international travel to a location with widespread COVID-19 transmission. These include workers who have contact with the general public such as in schools, high-population-density work environments, and some high-volume retail settings.[1]:18–20

Engineering controls for this and higher risk groups include installing high-efficiency air filters, increasing ventilation rates, installing physical barriers such as clear plastic sneeze guards, and installing a drive-through window for customer service.[1]:12–13

Administrative controls for this and higher risk groups include encouraging sick workers to stay at home, replacing face-to-face meetings with virtual communications, establishing staggered shifts, discontinuing nonessential travel to locations with ongoing COVID-19 outbreaks, developing emergency communications plans including a forum for answering workers’ concerns, providing workers with up-to-date education and training on COVID-19 risk factors and protective behaviors, training workers who need to use protecting clothing and equipment how to use it, providing resources and a work environment that promotes personal hygiene, requiring regular hand washing, limiting customers' and the public's access to the worksite, and posting signage about hand washing and other COVID-19 protective measures.[1]:13–14, 21–22

Depending on the work task, workers with at least medium exposure risk may need to wear personal protective equipment including some combination of gloves, a gown, a face shield or face mask, or goggles. Workers in this risk group rarely require use of respirators.[1]:22

Food service and processing

For retail workers in food and grocery businesses, CDC and OSHA recommend specific COVID-19 hazard controls above the general workplace practices. For employees, these include encouraging touchless payment options and minimizing handling of cash and credit cards, placing cash on the counter rather than passing it directly by hand, and routinely disinfecting frequently touched surfaces such as workstations, cash registers, payment terminals, door handles, tables, and countertops. Employers may place sneeze guards with a pass-through opening at the bottom of the barrier in checkout and customer service locations, use every other check-out lane, move the electronic payment terminal farther from the cashier, place visual cues such as floor decals to indicate where customers should stand during check out, provide remote shopping alternatives, and limit the maximum customer capacity at the door.[11]

.png)

Meat and poultry processing facilities are considered critical infrastructure workers, and CDC advises that they may be permitted to continue work following potential exposure to COVID-19, provided they remain asymptomatic and additional precautions are implemented to protect them and the community. However, their work environments may contribute substantially to their potential exposures, as they often work close to one another on processing lines during prolonged work shifts. For engineering controls, CDC and OSHA recommend configuring communal work environments so that workers are spaced at least six feet apart including along processing lines, using physical barriers such as strip curtains or plexiglass to separate workers from each other, and ensuring adequate ventilation that minimizes air from fans blowing from one worker directly at another worker. For administrative controls, they recommend staggering workers' arrival, break, and departure times, cohorting workers so they are always assigned to the same shifts with the same coworkers, encouraging single-file movement through the facility, avoiding carpooling to and from work, and considering a program of screening workers before entry into the workplace and setting criteria for return to work of recovered workers and for exclusion of sick workers. For personal protective equipment, they recommend face shields and considering allowing voluntary use of filtering facepiece respirators such as N95 masks. They also recommend wearing cloth face masks that should be replaced if they become wet, soiled, or otherwise visibly contaminated during the work shift, although cloth face masks are not considered to be personal protective equipment.[12]

Transportation

If a person becomes sick on an airplane, proper controls to protect workers and other passengers include separating the sick person from others by a distance of 6 feet, designating one crew member to serve the sick person, and offering a face mask to the sick person or asking the sick person to cover their mouth and nose with tissues when coughing or sneezing. Cabin crew should wear disposable medical gloves when tending to a sick traveler or touching body fluids or potentially contaminated surfaces, and possibly additional personal protective equipment if the sick traveler has fever, persistent cough, or difficulty breathing. Gloves and other disposable items should be disposed of in a biohazard bag, and contaminated surfaces should be cleaned and disinfected afterwards.[13]

For commercial shipping, including cruise ships and other passenger vessels, hazard controls include postponing travel when sick, and self-isolating and informing the onboard medical center immediately if one develops a fever or other symptoms while on board. Ideally, medical follow-up should occur in the isolated person's cabin.[14]

Other sectors

For schools and childcare facilities, CDC recommends short-term closure to clean or disinfect if an infected person has been in a school building regardless of community spread. When there is minimal to moderate community transmission, social distancing strategies can be implemented such as canceling field trips, assemblies, and other large gatherings such as physical education or choir classes or meals in a cafeteria, increasing the space between desks, staggering arrival and dismissal times, limiting nonessential visitors, and using a separate health office location for children with flu-like symptoms. When there is substantial transmission in the local community, in addition to social distancing strategies, extended school dismissals may be considered.[15]

For law enforcement personnel performing daily routine activities, the immediate health risk is considered low by CDC. Law enforcement officials who must make contact with individuals confirmed or suspected to have COVID-19 are recommended to follow the same guidelines as emergency medical technicians, including proper personal protective equipment. If close contact occurs during apprehension, workers should clean and disinfect their duty belt and gear prior to reuse using a household cleaning spray or wipe, and follow standard operating procedures for the containment and disposal of used PPE and for containing and laundering clothes.[16]

High-risk healthcare and mortuary workplaces

OSHA considers certain healthcare and mortuary workers to be at high or very high categories of exposure risk. High exposure risk jobs include healthcare delivery, support, laboratory, and medical transport workers who are exposed to known or suspected COVID-19 patients. These become very high exposure risk if workers perform aerosol-generating procedures on, or collect or handle specimens from, known or suspected COVID-19 patients. Aerosol-generating procedures include intubation, cough induction procedures, bronchoscopies, some dental procedures and exams, or invasive specimen collection. High exposure risk mortuary jobs include workers involved in preparing the bodies of people who had known or suspected cases of COVID-19 at the time of their death; these become very high exposure risk if they perform an autopsy.[1]:18–20

Additional engineering controls for these risk groups include isolation rooms for patients with known or suspected COVID-19, including when aerosol-generating procedures are performed. Specialized negative pressure ventilation may be appropriate in some healthcare and mortuary settings. Specimens should be handled with Biosafety Level 3 precautions.[1]:13, 23–24 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that incoming patients be separated into distinct waiting areas depending on whether they are a suspected COVID-19 case.[17]

In addition to other PPE, OSHA recommends respirators for those who work within 6 feet of patients known to be, or suspected of being, infected with SARS-CoV-2, and those performing aerosol-generating procedures. In the United States, NIOSH-approved N95 filtering facepiece respirators or better must be used in the context of a comprehensive, written respiratory protection program that includes fit-testing, training, and medical exams. Other types of respirators can provide greater protection and improve worker comfort.[1]:14–16, 25

The WHO does not recommend coveralls, as COVID-19 is a respiratory disease rather than being transmitted through bodily fluids.[17][18] WHO recommends only a surgical mask for point-of-entry screening personnel. For those who are collecting respiratory specimens from, caring for, or transporting COVID-19 patients without any aerosol-generating procedures, WHO recommends a surgical mask, goggles, or face shield, gown, and gloves. If an aerosol-generating procedure is performed, the surgical mask is replaced with an N95 or FFP2 respirator.[17] Given that the global supply of PPE is insufficient, WHO recommends minimizing the need for PPE through telemedicine, physical barriers such as clear windows, allowing only those involved in direct care to enter a room with a COVID-19 patient, using only the PPE necessary for the specific task, continuing use of the same respirator without removing it while caring for multiple patients with the same diagnosis, monitoring and coordinating the PPE supply chain, and discouraging the use of masks for asymptomatic individuals.[18]

Return to work

As business reopen across the world, measures are being developed to re-integrate workers in a manner that minimizes risks of transmission of COVID-19. Tools and publications with approaches to be taken to help with a safe and healthy return to work have been published by several health agencies and professional organizations. Examples include tool kits with fact sheets for workers and employers, infographics, and checklists for readiness to return to work.

Workers' rights

In the United States, Section 11(c) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 prohibits employers from retaliating against workers for raising concerns about safety and health conditions. OSHA encourages workers who suffer such retaliation to submit a complaint to OSHA's Whistleblower Protection Program within the legal time limits.[12][19]

References

![]()

![]()

- "Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19" (PDF). U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. March 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - Interim Guidance for Businesses and Employers". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- "Hierarchy of Controls". U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- Jh, Verbeek; B, Rajamaki; S, Ijaz; R, Sauni; E, Toomey; B, Blackwood; C, Tikka; Jh, Ruotsalainen; Fs, Kilinc Balci (2020-04-15). "Personal Protective Equipment for Preventing Highly Infectious Diseases Due to Exposure to Contaminated Body Fluids in Healthcare Staff". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011621. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub4. PMC 7158881. PMID 32293717.

- Danovaro-Holliday MC, LeBaron CW, Allensworth C, Raymond R, Borden TG, Murray AB, et al. (December 2000). "A large rubella outbreak with spread from the workplace to the community". JAMA. 284 (21): 2733–9. doi:10.1001/jama.284.21.2733. PMID 11105178.

- Edwards CH, Tomba GS, de Blasio BF (June 2016). "Influenza in workplaces: transmission, workers' adherence to sick leave advice and European sick leave recommendations". European Journal of Public Health. 26 (3): 478–85. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckw031. PMC 4884332. PMID 27060594.

- Baker MG, Peckham TK, Seixas NS (2020-04-28). Nelson CC (ed.). "Estimating the burden of United States workers exposed to infection or disease: A key factor in containing risk of COVID-19 infection". PLOS ONE. 15 (4): e0232452. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232452. PMC 7188235. PMID 32343747.

- Wise J (May 2020). "Covid-19: Low skilled men have highest death rate of working age adults". BMJ. 369: m1906. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1906. PMID 32398229. S2CID 218619587.

- Lan FY, Wei CF, Hsu YT, Christiani DC, Kales SN (2020-05-19). Shaman J (ed.). "Work-related COVID-19 transmission in six Asian countries/areas: A follow-up study". PLOS ONE. 15 (5): e0233588. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233588. PMC 7237000. PMID 32428031.

- "COVID-19: Back to the workplace - Adapting workplaces and protecting workers". OSHwiki. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- "What Grocery and Food Retail Workers Need to Know about COVID-19". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-04-13. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Meat and Poultry Processing Workers and Employers". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-04-26. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Updated Interim Guidance for Airlines and Airline Crew: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- "Interim Guidance for Ships on Managing Suspected Coronavirus Disease 2019". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - Interim Guidance for Administrators of US Childcare Programs and K-12 Schools". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- "What Law Enforcement Personnel Need to Know about Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-03-14. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- "The COVID-19 Risk Communication Package For Healthcare Facilities" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- "Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- "The Whistleblower Protection Program". U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

External links

- 24th Collegium Ramazzini statement. Prevention of work-related infection in the COVID-19 pandemic May 2020.

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Healthy workplaces. Stop the pandemic campaign materials

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, COVID-19: guidance for the workplace

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Back to the workplace: Adapting workplaces and protecting workers

- Office for National Statistics, UK, Which occupations have the highest potential exposure to the coronavirus (COVID-19)?

- U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health website on COVID-19

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Resuming Business Toolkit.

- Fact Sheet for Food and grocery pick-up and delivery drivers, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Fact Sheet for nail salon employers and employees on measures to protect against COVID-19 while at work.

- Fact Sheet for Firefighters and EMS Providers, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Fact Sheet for Grocery and food retail workers, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Fact Sheet for Mail and Parcel delivery drivers, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Fact Sheet for Rideshare and ride-for-hire drivers, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Resources related to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mining, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Guidance for Healthcare settings, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration website on COVID-19

- American Industrial Hygiene Association website on COVID-19

- The Synergist, American Industrial Hygiene Association, COVID-19 and the Industrial Hygienist

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work website on COVID-19

- UK Health Executive COVID-19 guidance for employees, employers, and businesses

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Safety and Health COVID-19 fact sheet