Hurricane Michael

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Michael at peak intensity making landfall on the Florida Panhandle on October 10 | |

| Formed | October 7, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | Currently active |

| (Extratropical after October 12) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 155 mph (250 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 919 mbar (hPa); 27.14 inHg |

| Fatalities | 33 total |

| Damage | > $8.1 billion (2018 USD) |

| Areas affected | Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Southeastern United States (especially the Florida Panhandle), East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Michael was the third-most intense Atlantic hurricane to make landfall in the United States in terms of pressure, behind the 1935 Labor Day hurricane and Hurricane Camille of 1969. It was also the strongest in terms of maximum sustained wind speed to strike the United States since Andrew in 1992. In addition, it was the strongest on record in the Florida Panhandle, and was the fourth-strongest landfalling hurricane in the contiguous United States, in terms of wind speed.

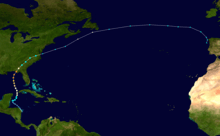

The thirteenth named storm, seventh hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season, Michael originated from a broad low-pressure area that formed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on October 2. The disturbance became a tropical depression on October 7, after nearly a week of slow development. By the next day, Michael had intensified into a hurricane near the western tip of Cuba as it moved northward. Strengthening continued in the Gulf of Mexico, first to a major hurricane on October 9, and further to a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale. Approaching the Florida Panhandle, Michael attained peak winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) as it made landfall near Mexico Beach, Florida, on October 10, becoming the first to do so in the region as a Category 4 hurricane, and making landfall as the strongest storm of the season. As it moved inland, the storm weakened and began to take a northeastward trajectory toward Chesapeake Bay, weakening to a tropical storm over Georgia, and transitioning into an extratropical cyclone off the coast of the Mid-Atlantic states on October 12.

By October 10, at least 33 deaths had been attributed to Michael and its precursor, including 18 in the United States and 15 in Central America. Insurance losses are estimated to be at least $8 billion (2018 USD).[1] The precursor to Michael caused extensive flooding in Central America in concert with a second disturbance over the eastern Pacific Ocean. In Cuba, the hurricane's winds left over 200,000 people without power as the storm passed to the island's west. Along the Florida panhandle, the cities of Mexico Beach and Panama City suffered the worst of Michael, with catastrophic damage reported due to the extreme winds and storm surge. Numerous homes were flattened and trees felled over a wide swath of the panhandle. A maximum wind gust of 129 mph (208 km/h) was measured at Tyndall Air Force Base near the point of landfall. As Michael tracked across the Southeastern United States, strong winds caused extensive power outages across the region.

Meteorological history

Early on October 2, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring a broad area of low pressure that had developed over the southwestern Caribbean Sea.[2] While strong upper-level winds initially inhibited development, the disturbance gradually became better organized as it drifted generally northward and then eastward toward the Yucatán Peninsula. By October 6, the disturbance had developed well-organized deep convection, although it still lacked a well-defined circulation. The storm was also posing an immediate land threat to the Yucatán Peninsula and Cuba. Thus, the NHC initiated advisories on Potential Tropical Cyclone Fourteen at 21:00 UTC that day.[3][4] By the morning of October 7, radar data from Belize found a closed center of circulation, while satellite estimates indicated a sufficiently organized convective pattern to classify the system as a tropical depression.[5] The newly-formed tropical cyclone then quickly strengthened into Tropical Storm Michael at 16:55 UTC that day.[6] The nascent system meandered before the center relocated closer to the center of deep convection, as reported by reconnaissance aircraft that was investigating the storm.[7] Despite moderate vertical wind shear, Michael proceeded to strengthen quickly, becoming a high-end tropical storm early on October 8, as the storm's cloud pattern became better organized.[8] Continued intensification occurred, and Michael attained hurricane status later on the same day.[9]

.jpg)

Shortly afterwards, rapid intensification began to ensue and very deep bursts of convection were noted within the eyewall of the growing hurricane, as it passed through the Yucatán Channel into the Gulf of Mexico late on October 8, clipping the western end of Cuba. Meanwhile, a 35 nmi (65 km) wide eye was noted to be forming.[10] The intensification process accelerated on October 9, with Michael becoming a major hurricane at 21:00 UTC that day.[11] In addition, the central pressure in the eye was noted to have dropped about 20 mb (0.59 inHg) in the span of 6 hours, into the first hours of October 10.[12] Rapid intensification continued throughout the day as a well-defined eye appeared, culminating with Michael achieving its peak intensity at 18:00 UTC that day as a high-end Category 4 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 919 mbar (27.14 inHg), just below Category 5 intensity, as it made landfall on the Gulf Coast of the United States near Mexico Beach, Florida, ranking by pressure as the third-most intense Atlantic hurricane to ever make landfall in the United States.[13]

Once inland, Michael began to rapidly weaken, as it moved over the inner Southeastern United States, with the eye dissipating from satellite view, weakening to a tropical storm roughly twelve hours after it made landfall.[14] Moving into the Carolinas early on October 11, the inner core collapsed as rainfall became prominent to the north of the center. Later that day, Michael began to show signs of becoming an extratropical cyclone, as it accelerated east-northeastward toward the Mid-Atlantic coastline, with cooler air beginning to wrap into the elongating circulation, due to an encroaching frontal zone.[15] Afterward, during the early hours of October 12, Michael began to restrengthen while moving off the coast, due to baroclinic forcing. Shortly afterward, Michael completed its extratropical transition around 09:00 UTC on the same day, as the storm became fully embedded within the frontal zone.[16]

Preparations

Cuba

About 300 people were evacuated in western Cuba due to the storm.[17]

United States

.jpg)

On October 7, Governor Rick Scott announced that he would be declaring a state of emergency for Florida if needed, advising residents to be prepared for the incoming storm.[18] That day, a state of emergency was declared for 26 counties, and then 9 additional counties were added on October 8. Governor Scott also requested that President Donald Trump issue an emergency disaster declaration for 35 counties, with Trump approving of the request on October 9.[19] Officials in Bay, Gulf, and Wakulla counties issued mandatory evacuation orders on October 8 for those living near the coast, in mobile homes, or in other weak dwellings.[20] Florida State University's main campus in Tallahassee and a satellite campus in Panama City, Florida, were closed from October 9 through October 12, with classes and business expected to resume on October 15. Florida A&M University and Tallahassee Community College are closing several campuses through October 14, while weekend classes and events were canceled at the former.[21] Public schools were closed in 26 counties, mainly in the Florida Panhandle.[19] On October 8, Hurricane and Tropical Storm Warnings and Watches were issued for the Gulf Coast.

Georgia Governor Nathan Deal declared a state of emergency for 92 counties in the southern and central portions of the state on October 9. Several colleges and universities in south Georgia were to close for a few days.[22]

375,000 people were asked to evacuate as the storm strengthened, with sustained winds of 150 mph and storm surge up to 14 feet expected.[23]

Impact

Central America

| Country | Deaths |

|---|---|

| United States | 18[24] |

| Honduras | 8 |

| Nicaragua | 4 |

| El Salvador | 3 |

| Total | 33 |

The combined effects of the precursor low to Michael and a disturbance over the Pacific Ocean caused significant flooding across Central America.[25] At least 15 fatalities occurred: 8 in Honduras,[26] 4 in Nicaragua, and 3 in El Salvador.[25][27] In Honduras, torrential rain caused at least seven rivers to overtop their banks; nine communities became isolated. More than 1,000 homes sustained damage, of which 9 were destroyed, affecting more than 15,000 people. Nationwide, 78 shelters housed displaced persons and relief agencies procured 36 tonnes of aid.[26] Nearly 2,000 homes in Nicaragua suffered damage, and 1,115 people were evacuated. A total of 253 homes were damaged in El Salvador.[25] Damage across the region exceeded $100 million.[28]

Cuba

About 70% of the offshore Isla de la Juventud lost power.[29] High winds left 200,651 people without power in the province of Pinar del Río.[17] Officials sent 500 power workers to the area to restore electricity.[17]

United States

Michael made landfall as a high-end Category 4 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h), at 12:15 CDT (17:15 UTC) on October 10, in Mexico Beach, Florida, and near Tyndall Air Force Base.[30] In Mexico Beach, many homes were flattened or completely swept away by storm surge and several roofs landed on U.S. Route 98. The National Guard rescued about 20 people, while it was estimated that as many as 285 residents of the small town may have stayed. Major damage occurred at Tyndall Air Force Base, with nearly every house at the base suffering roof damage. A wind gust of 129 mph (208 km/h) was recorded at the base. Debris on Interstate 10 resulted in the roadway being closed between Lake Seminole and Tallahassee, a distance of about 80 mi (130 km). In Tallahassee, a number of trees fell across the city and approximately 110,000 businesses and homes were left without electricity, while a sewer system failed. In Chattahoochee, the Florida State Hospital – the oldest and largest psychiatric hospital in the state – became isolated, forcing aid to be dropped by helicopter. Four deaths occurred in Gadsden County,[31] and another three deaths occurred in Marianna, Jackson County. A body was discovered by rescue crews in Mexico Beach on October 12.[24]

In Georgia, wind gusts peaked at 115 mph (185 km/h) in Donalsonville. Tropical storm force wind gusts were observed as far north as Athens and Atlanta. More than 400,000 electrical customers in Georgia were left without power. At least 127 roads throughout the state were blocked by fallen trees or debris.[32] In Albany, 24,270 electrical customers lost power. Several trees fell on homes and roads, blocking about 100 intersections. Winds also ripped siding off of homes and shattered windows at the convention center. A tornado in Crawford County damaged seven homes.[33] An 11-year old girl in Seminole County died after a carport hit her home.[32] Losses due to crop damage in Georgia were expected to exceed US$1 billion.[24]

As the storm passed through North Carolina, 490,000 Duke Energy customers were left without power late on October 11. 342,000 remained without power in the state 24 hours later.[34] A tree fell on a car in Statesville, killing the driver.[35] Two others died in Marion when they crashed into a tree that had fallen across a road.[24]

In Virginia, four people including a firefighter were washed away by floodwaters, and another firefighter was killed in a vehicle accident on Interstate 295.[36] A sixth fatality was discovered when the body of a woman was found on October 13.[37] An EF1 tornado caused US$1.8 million in damage in Norge. At least 1,200 roads were closed, and hundreds of trees were downed. Up to 600,000 people were left without power at the height of the storm.[24]

| Most intense landfalling tropical cyclones in the United States Intensity is measured solely by central pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | System | Season | Landfall pressure |

| 1 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 mbar (hPa) |

| 2 | Camille | 1969 | 900 mbar (hPa) |

| 3 | Michael | 2018 | 919 mbar (hPa) |

| 4 | Katrina | 2005 | 920 mbar (hPa) |

| Maria | 2017 | ||

| 6 | Andrew | 1992 | 922 mbar (hPa) |

| 7 | "Indianola" | 1886 | 925 mbar (hPa) |

| 8 | "Guam" | 1900 | 926 mbar (hPa) |

| 9 | "Florida Keys" | 1919 | 927 mbar (hPa) |

| 10 | "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 929 mbar (hPa) |

| Source: HURDAT,[38] Hurricane Research Division[39] | |||

Impact on radio and television broadcasts

Panama City's proximity to the eyewall and its associated strongest winds and storm surge resulted in the majority, if not all, of the city's television and radio stations being rendered inoperable during and after the height of landfall. NBC affiliate WJHG-TV (channel 7) and CBS affiliate WECP-LD (channel 18) – both owned by Gray Television – were the first broadcast outlets to be affected, as their studio/transmitter link tower (which also housed the main transmitter for ESPN Radio affiliate WGSX [104.3 FM]) collapsed around 12:00 p.m. CDT on October 10, and parts of the roof of WJHG/WECP's studio facility were torn off.[40]

ABC affiliate WMBB (channel 13) subsequently lost its main power and its backup generator around 12:15 p.m. CDT. (WMBB provided live coverage from its Nexstar Media Group-owned sister stations WFLA-TV in Tampa and WDHN in Dothan, Alabama (the latter of which, alongside Gray-owned CBS affiliate WTVY was also knocked off the air later that same day as Michael passed over the Wiregrass Region) on its website and cable feed afterward.) iHeartMedia's Panama City radio cluster – WDIZ (590 AM), WEBZ (99.3 FM), WFLF-FM (94.5), WFSY (98.5 FM) and WPAP (92.5 FM) – switched to programming from the company's Tallahassee cluster as Michael made landfall, before the STL tower at their facility was felled; station staff were reported trapped at the facility due to flooding that also crept into the building.[40]

The respective radio clusters owned by Powell Broadcasting (WASJ [105.1 FM], WKNK [103.5 FM], WPFM [107.9 FM] and WRBA [95.9 FM]) and Magic Broadcasting II (WILN [105.9 FM], WWLY [100.1 FM], WYOO [101.1 FM] and WYYX [97.7 FM]), and Gulf Coast Community College-owned WKGC-AM-FM (1480 and 90.7) were also knocked off the air due to tower collapses or lost power. (WPAP and WFSY returned to the air during the evening of October 10 with locally originated coverage, with WKGC following suit with programming originating from the Bay County Emergency Operations Center and using WMBB staff.)[40]

Aftermath

On October 9 – a day before Hurricane Michael made landfall – President Donald Trump signed an emergency declaration for Florida, which authorized the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to coordinate disaster efforts, with Thomas McCool serving as Federal Coordinating Officer in the state. The declaration also authorized funding for 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures and the removal of storm debris in 14 Florida counties. The federal government also provided for 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures in an additional 21 counties.[41] On October 11, President Trump declared a major disaster in five counties: Bay, Franklin, Gulf, Taylor, and Wakulla. Residents in the county were able to receive grants for house repairs, temporary shelter, loans for uninsured property losses, and business loans.[42]

Due to the storm damage in Georgia, President Trump also signed an emergency declaration for Georgia, where FEMA activity was coordinated by Manny J. Torro. The declaration authorized funding for 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures and the removal of storm debris in 31 Georgia counties, and 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures in an additional 77 counties.[43]

Records

With top sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a central pressure of 919 mbar (hPa; 27.14 inHg) at landfall, Michael is the most intense landfalling U.S. hurricane since Camille in 1969, which had a central pressure of 900 mbar (hPa; 26.58 inHg), and the strongest by wind speed since Andrew in 1992, which had 165 mph (270 km/h) winds.[30] Along with 2017's Hurricane Maria and a typhoon in 1900, Michael is tied for the sixth-strongest tropical cyclone by wind to impact the United States (including its overseas territories), and is the fourth strongest to impact the U.S. mainland.[44] Additionally, Michael is the second-most-intense hurricane by pressure to make landfall in Florida, behind the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, and the third strongest by wind, behind the 1935 hurricane and Andrew.[45]

Michael is the most intense recorded hurricane to have made landfall during the month of October in the North Atlantic basin (including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea),[46] and is one of only two Category 4 hurricanes to have made landfall in Florida in October – the other being Hurricane King in 1950.[47] Michael is also the first recorded Category 4 hurricane to strike the Florida Panhandle since reliable records began in 1851.[48]

As it moved inland into southwestern Georgia, Michael weakened to a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h),[49] becoming the first storm to impact the state as a major hurricane since 1898.[50]

See also

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Florida hurricanes

- Hurricane Eloise (1975) – Category 3 hurricane that impacted the Gulf Coast of Florida.

- Hurricane Frederic (1979) – Category 4 hurricane that impacted the Gulf Coast, particularly Alabama.

- Hurricane Opal (1995) – Impacted Mexico and Central America in its early stages, before striking the Florida Panhandle as a major hurricane.

- Hurricane Ivan (2004) – Impacted the Gulf Coast of Alabama and the western Florida Panhandle as a Category 3 hurricane.

- Hurricane Dennis (2005) – The last major hurricane to strike the Florida Panhandle before Michael.

References

- ↑ "Hurricane Michael Caused Estimated $8 Billion in Insured Losses". TIME. October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (October 2, 2018). "NHC Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Jack Beven (October 6, 2018). "Potential Tropical Cyclone Fourteen Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ John L. Beven (October 6, 2018). "Potential Tropical Cyclone Fourteen Discussion Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ Robbie Berg (October 7, 2018). "Tropical Depression Fourteen Discussion Number 3". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (October 7, 2018). "Tropical Storm Michael Tropical Cyclone Update". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (October 7, 2018). "Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 4". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Robbie Berg (October 8, 2018). "Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 6". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (October 8, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 8". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart (October 8, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 10". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (October 9, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 13". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart (October 9, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 14". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Intermediate Advisory 16A". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ↑ Jack Beven (October 10, 2018). "Tropical Storm Michael Tropical Cyclone Update". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (October 11, 2018). "Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 21". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ Robbie Berg (October 12, 2018). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Michael Discussion Number 23". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Huracán Michael deja daños significativos en Cuba" (in Spanish). Conexión Capital. October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ↑ Ron Brackett (October 7, 2018). "Florida Governor to Declare State of Emergency Ahead of Potential Hurricane Threat". Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 "Gov. Scott: Federal Pre-Landfall Emergency Declaration Signed by the President". Florida Division of Emergency Management. October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ↑ Amber Roberson (October 8, 2018). "Hurricane Michael: First Florida evacuations ordered in Gulf County, others in panhandle". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ↑ "FSU closing Tuesday-Friday due to Hurricane Michael". WPTV. October 8, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ↑ Eric Strigus (October 9, 2018). "South Georgia college campuses closing in preparation of Hurricane Michael". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Hurricane Michael - LIVE: Tropical cyclone on path for Florida hits Category 4 with 130mph winds". The Independent. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wright, Pam (October 13, 2018). "Michael Death Toll Climbs to 18; Search Continues for Missing". The Weather Channel. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Tres muertos y más de 1900 viviendas afectadas por lluvias". Confidencial (in Spanish). October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 "Sube a ocho el número de muertos por las lluvias en Honduras". El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Al menos 9 muertos y miles de afectados por un temporal en Centroamérica" (in Spanish). October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Steven Bown [@SteveBowenWx] (October 12, 2018). "Prior to officially developing into #Michael, the disorganized cluster of storms spawned torrential rains in Central America. At least 13 killed. Economic damage already listed in excess of $100M to property & infrastructure" (Tweet). Retrieved October 12, 2018 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Benjamín Morales (October 8, 2018). "Michael se aleja de Cuba tras dejar daños en el occidente" (in Spanish). El Nuevo Dia. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Michael devastates Mexico Beach, Florida, in historic Category 4 landfall". Sun-Sentinel. October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ↑ Ron Brackett (October 11, 2018). "6 Killed As Michael Treks Through Southeast Leaving Florida Beach Towns in Ruins, Flooding Parts of North Carolina, Virginia Towns". The Weather Channel. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- 1 2 Mitchell Northam; Becca J. G. Godwin; Raisa Habersham (October 11, 2018). "Hurricane Michael in Georgia: Damage by the numbers". The Atlanta Journal Constitution. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ Ben Brasch; Johnny Edwards; Christian Boone (October 11, 2018). "Hurricane Michael: Damage in Georgia is 'phenomenal'". The Atlanta Journal Constitution. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ Bruce henderson (October 12, 2018). "More than 400,000 in Carolinas still without power after Tropical Storm Michael". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ "1st death reported in NC from Michael". CBS 17 News. October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ Hedgpeth, Dana. "Five people are dead, 1,200 roads closed and half-a-million people are without power after Michael ravages Virginia". The Washington Post (October 12, 2018). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Death toll from TS Michael up to 6 in Virginia". WHSV-TV3. October 13, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ↑ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". Hurricane Research Division (Database). National Hurricane Center. May 1, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (May 2018). "Continental United States Hurricanes (Detailed Description)". AOML. Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Lance Venta (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Takes Panama City Off The Air". Radio Insight. RadioBB Networks. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ "President Donald J. Trump Signs Emergency Declaration for Florida". FEMA. October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ "President Donald J. Trump Approves Major Disaster Declaration for Florida". FEMA. October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ "President Donald J. Trump Signs Emergency Declaration for Georgia". FEMA. October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ↑ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (10 October 2018). "Table of 10 strongest continental US landfalling #hurricanes on record as ranked by maximum sustained wind. Michael ranks 4th with sustained winds of 135 knots (155 mph) at landfall" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 October 2018 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Klotzbach, Philip (October 11, 2018). "Michael made history as one of the top four strongest hurricanes to strike the United States". Washington Post. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Uhlhorn, Eric; Lorsolo, Sylvie (10 October 2018). "Why Hurricane Michael's Landfall Is Historic". Air-Worldwide. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ↑ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (10 October 2018). "Michael is the 2nd October Category 4 hurricane on record to make landfall in Florida - the other was Hurricane King in 1950" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 October 2018 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (10 October 2018). "Hurricane Michael has made landfall with max sustained winds of 155 mph - the first Category 4 hurricane to make landfall in the Florida Panhandle on record" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 October 2018 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Update Statement". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ↑ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (10 October 2018). "The last major (Category 3+) hurricane to track into Georgia was the Georgia Hurricane of 1898 (which made landfall in Camden County, GA). Since that time, no major hurricanes have made landfall in Georgia or have tracked into Georgia at major hurricane strength. Michael" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 October 2018 – via Twitter.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Michael (2018). |

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Michael

- EMSR322: Hurricane Michael over the coast of Florida, Alabama and Georgia (delineation maps) – Copernicus Emergency Management Service