Lake Okeechobee

| Lake Okeechobee | |

|---|---|

from space, September 1988 | |

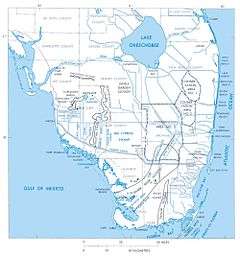

Shown in blue on map of South Florida | |

| Location | Florida |

| Coordinates | 26°56′N 80°48′W / 26.933°N 80.800°WCoordinates: 26°56′N 80°48′W / 26.933°N 80.800°W |

| Primary inflows | Kissimmee River, Fisheating Creek, Taylor Creek |

| Primary outflows | Everglades, Caloosahatchee River, St. Lucie River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 36 mi (57.5 km) |

| Max. width | 29 mi (46.6 km) |

| Surface area | 734 sq mi (1,900 km2) |

| Average depth | 8 ft 10 in (2.7 m) |

| Max. depth | 12 ft (3.7 m) |

| Water volume | 1 cu mi (5.2 km3) (estimated) |

| Surface elevation | 12 to 18 ft (3.74 to 5.49 m) |

| Islands | Kreamer, Torry, Ritta, Grass, Observation, Bird, Horse, Hog, Eagle Bay |

Lake Okeechobee (US: /oʊkiˈtʃoʊbi/),[1] also known as Florida's Inland Sea,[2] is the largest freshwater lake in the state of Florida.[3] It is the ninth largest natural freshwater lake in the United States and the second largest natural freshwater lake (the largest being Lake Michigan) contained entirely within the contiguous United States.[4] Okeechobee covers 730 square miles (1,900 km2), approximately half the size of the state of Rhode Island, and is exceptionally shallow for a lake of its size, with an average depth of only 9 feet (2.7 metres). The lake is divided between Glades, Okeechobee, Martin, Palm Beach, and Hendry counties. All five counties meet at one point near the center of the lake.[5]

History

The name Okeechobee comes from the Hitchiti words oki (water) and chubi (big). Mayaimi, meaning "big water," is the oldest known name, as reported in the 16th century, by Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda.[6] Slightly later in the 16th century René Goulaine de Laudonnière reported hearing about a large freshwater lake in southern Florida called Serrope.[7] By the 18th century the largely mythical lake was known to British mapmakers and chroniclers by the Spanish name Laguna de Espiritu Santo.[8] In the early 19th century it was known as Mayacco Lake or Lake Mayaca after the Mayaca people, originally from the upper reaches of the St. Johns River, who moved near the lake in the early 18th century.[9] The modern Port Mayaca on the east side of the lake preserves that name.[10]

On the southern rim of Lake Okeechobee, three islands—Kreamer, Ritta, and Torey—were once settled by early pioneers. These settlements had a general store, post office, school, and town elections. Farming was the main vocation. The fertile land was challenging to farm because of the muddy muck. Over the first half of the twentieth century, farmers used agricultural tools—including tractors—to farm in the muck. By the 1960s, all of these settlements were abandoned.[11]

Hurricanes

In 1926 the Great Miami Hurricane hit the Lake Okeechobee area, killing approximately 300 people. Two years later in 1928, the Okeechobee Hurricane crossed over the lake, killing thousands. The Red Cross reported 1,836 deaths which the National Weather Service initially accepted, but in 2003, the number was revised to "at least 2,500".[12] In both cases the catastrophe was caused by flooding from a storm surge when strong winds drove water over the 6.6-foot (2-meter) mud dike that circled the lake at the time.

After the two hurricanes, the Florida State Legislature created the "Okeechobee Flood Control District". The organization was authorized to cooperate with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in actions to prevent similar disasters. U.S. President Herbert Hoover visited the area personally, and afterward the Corps designed a plan incorporating the construction of channels, gates, and levees. The Okeechobee Waterway was officially opened on 23 March 1937 by a procession of boats which left Fort Myers, Florida on 22 March and arrived at Stuart, Florida the following day. The dike was then named the "Herbert Hoover Dike" in honor of the president.

The 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane sent an even larger storm surge to the crest of the new dike, causing it to be expanded again in the 1960s.

Four recent hurricanes - Frances, Jeanne, Wilma, and Irma – had no major adverse effects on communities surrounding Lake Okeechobee, even though the lake rose 18 inches (46 cm) after Hurricane Wilma in 2005. Tropical Storm Ernesto increased water levels by 1 foot (30 cm) in 2006, the last time it exceeded 13 feet (4.0 m).[13] However, the lake's level began dropping soon after and by July 2007, it had dropped more than 4 feet (1.2 m) to its all-time low of 8.82 feet (2.69 m). In August 2008, Tropical Storm Fay increased water levels to 2 feet (0.65 m) above sea level, the first time it exceeded 12 feet (3.66 m) since January 2007. Over a seven-day period (including some storms that preceded Fay), about 8 inches (20 cm) of rain fell directly onto the lake.[13]

Rim Canal

During construction of the dike, earth was excavated along the inside perimeter, resulting in a deep channel which runs along the perimeter of the lake.[4] In most places the canal is part of the lake, but in others it is separated from the open lake by low grassy islands such as Kreamer Island. During the drought of 2007–2008 this canal remained navigable while much of surrounding areas were too shallow or even above the water line. Even when the waters are higher, navigating the open lake can be tricky, whereas the rim canal is simple, so to reach a specific location in the lake it is often easiest to go around the rim canal to get close then take one of the many channels into the lake.

Environmental concerns

In 2007, during a drought, state water and wildlife managers removed thousands of truckloads of toxic mud from the lake's floor, in an effort to restore the lake's natural sandy base and create clearer water and better habitat for wildlife. The mud contained elevated levels of arsenic and other pesticides. According to tests from the South Florida Water Management District, arsenic levels on the northern part of the lake bed were as much as four times the limit for residential land. Independent tests found the mud too polluted for use on agricultural or commercial lands, and therefore difficult to dispose of on land.[14]

Through early 2008, the lake remained well below normal levels, with large portions of the lake bed exposed above the water line. During this time, portions of the lake bed, covered in organic matter, dried out and caught fire.[15] In late August 2008, Tropical Storm Fay inundated Florida with record amounts of rain. Lake Okeechobee received almost a 4 feet (1.2 m) increase in water level, including local run-off from the tributaries.

In 2013 heavy rains in central Florida resulted in high runoff into the lake; rising lake levels forced the CoE (Army Corps of Engineers) to release large volumes of polluted water from the lake through the St. Lucie River estuary to the east and the Caloosahatchee River estuary to the west. Thus the normal mix of fresh and salt water in those estuaries was replaced by a flood of polluted fresh water resulting in ecological damage.[16]

Since 2013, the CoE has been forced to pump billions of gallons (billions of cubic meters) of water out of the lake to avoid jeopardizing the integrity of the Hoover dike holding back the water from inundating the surrounding populated area. Some claim that sugar plantations have been pumping polluted water from their flooded fields into the lake, but U.S. Sugar claims back pumping is only to avoid flooding of communities, never to protect farm land. In March 2015, the rate was 1 billion US gallons (3,785,412 m3) daily. This results in pollution problems for the Treasure Coast, St. Lucie estuary, and the Indian River Lagoon.[17][18]

In May 2016, 33 square miles (85 km2) of the southern portion of the lake were affected by an algal bloom.[19] The outbreak was possibly due in part to nutrient-laden waters reaching the lake from farms and other sources.[19][20] Microcystin was found among the other species involved in the outbreak.[19]

In July 2016, the Federal Government denied Governor Rick Scott's request for Federal Disaster Aid to the Treasure Coast as a result of the toxic algal bloom in the St. Lucie Estuary which was responsible for millions of dollars of lost income for local businesses: this reaffirmed the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) finding that the lake's water quality was a State issue. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection and Martin County had carried out toxicity testing on the algae, but had not funded any work to clean up the water, and a FEMA spokesman said that "The state has robust capability to respond to emergencies and disasters."[21]

On June 23, 2017, the South Florida Water Management District was granted emergency permission to back pump clean water into Lake Okeechobee to save animals and plants in bloated water conservation areas."[22]

Geology

Lake Okeechobee sits in a shallow geological trough that also underlies the Kissimmee River Valley and the Everglades. The trough is underlain by clay deposits that compacted more than the limestone and sand deposits did along both coasts of peninsular Florida. Until about 6,000 years ago, the trough was dry land. As the sea level rose, the water table in Florida also rose and rainfall increased. From 6,000 to 4,000 years ago, wetlands formed building up peat deposits. Eventually the water flow into the area created a lake, drowning the wetlands. Along what is now the southern edge of the lake, the wetlands built up the layers of peat rapidly enough (reaching 13-to-14-foot or 4-to-4.3-metre thick) to form a dam, until the lake overflowed into the Everglades.[23] At its capacity, the lake holds 1 trillion US gallons (3.8×109 m3) of water[13] and is the headwaters of the Everglades.[24]

The floor of the lake is a limestone basin, with a maximum depth of 13 feet (4 m). Its water is somewhat murky from runoff from surrounding farmlands. The Army Corps of Engineers targets keeping the surface of the lake between 12.5 and 15.5 feet (4 and 5 m) above sea level.[25] The lake is enclosed by a 40 feet (12 m) high Herbert Hoover Dike built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after a hurricane in 1928 breached the old dike, flooding surrounding communities and claiming at least 2,500 lives.[26] Water flows into Lake Okeechobee from several sources, including the Kissimmee River, Fisheating Creek, Lake Istokpoga, Taylor Creek, and smaller sources such as Nubbin Slough and Nicodemus Slough.[27][28] The Kissimmee River is the largest source, providing more than 60% of the water flowing into Lake Okeechobee.[29][30] Fisheating Creek is the second largest source for the lake, with about 9% of the total inflow.[28] Prior to the 20th century, Lake Istokpoga was connected to the Kissimee River by Istokpoga Creek, but during the rainy season Lake Istokpoga overflowed, with the water flowing in a 40 km wide sheet across the Indian Prairie into Lake Okeechobee.[31] Today Lake Istokpoga drains into Lake Okeechobee through several canals that drain the Indian Prairie, and into the Kissimmee River through a canal that has replaced Istokpoga Creek.[32] Historically, outflow from the lake was by sheet flow over the Everglades, but most of the outflow has been diverted to dredged canals connecting to coastal rivers, such as the Miami Canal to the Miami River, the New River on the east, and the Caloosahatchee River (via the Caloosahatchee Canal and Lake Hicpochee) on the southwest.

Uses

Congressionally authorized uses for Lake Okeechobee

According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,[33] the Congressionally authorized uses for Lake Okeechobee include the following:

- Flood and storm risk management

- Navigation

- Water supply for the following:

- Salinity control in estuaries

- Regional groundwater control

- Agricultural irrigation

- Municipalities and industry

- Enhancement of fish and wildlife

- Recreation

National Scenic Trail

The 30-metre (100 ft) wide dike surrounding Lake Okeechobee is the basis for the Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail (LOST), a part of the Florida National Scenic Trail, a 1,300-mile-long (2,100 km) trail that is a National Scenic Trail. There is a well-maintained paved pathway along the majority of the perimeter, although with significant breaks.[34] It is used by hikers and bicyclists, and is wide enough to accommodate vehicles.

Fishing

The most common fish in this lake are largemouth bass, crappie, and bluegill. Pickerel have been less commonly caught.

In popular culture

Lake Okeechobee and the Everglades are featured as a backdrop for the 1951 Gary Cooper film, Distant Drums.

Lake Okeechobee is the setting of a climactic scene in Carl Hiaasen's 2002 novel Basket Case (Ch. 28).

Used in the John Anderson song "Seminole Wind" Lyric: "And blow, blow from the Okeechobee, All the way up to Micanopy".

Lake Okeechobee is the setting of a significant part of Zora Neale Hurston's novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, and the movie of the same name. Janie and Tea Cake go there to work "on the muck." Hurston refers to the lake as "Big Lake Okechobee, big beans, big cane, big weeds, big everything". The description speaks to the migrant African American laborers working in this area during the agricultural season in the 1920s.[35]

Lake Okeechobee and the Everglades are settings in Patrick D. Smith's novel A Land Remembered, chronicling the effects of modernization upon the lake and the Seminole tribe.

Lake Okeechobee is famously mentioned in Hank Williams Jr.'s number one Billboard country hit song "Dixie on My Mind", in 1981. When comparing country life to big city life: "I've always heard lots about the big apple / So I thought I'd come up here and see. / But all I've seen so far is one big hassle / wish I was camped out on the Okeechobee'".

Lake Okeechobee is featured in the first episode of American Horror Story: Freak Show.

PBS Video

In 2007, PBS's Earth Edition produced a 27-minute video titled Lake Okeechobee: Big Water, Big Trouble. Earth Edition's description of the video follows: During the past 125 years, a series of well-intentioned decisions, actions and policies have turned what should have been one of Florida's greatest natural treasures into an environmental villain. Six thousand years later after it was formed, residents and agencies across the state are now raising the questions: Is it too late for Lake O?[36]

Star Trek: Enterprise

Charles "Trip" Tucker III, (short for "Triple", since he is the third generation of his family to be named Charles Tucker), played by Connor Trinneer, is a fictional character in the television series Star Trek: Enterprise. According to Star Trek lore, "Trip" had a sister who was killed by the Xindi along with 7 million other Humans in the year 2153. The CGI depiction of the attack on Earth in The Expanse (Star Trek: Enterprise episode) shows that the beam hits on the west side of Lake Okeechobee in Glades County and cuts a swath directly south, through Hendry County and Cuba, until reaching South America.

Notes

- ↑ "Okeechobee". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Lake Okeechobee Area, Visit Florida

- ↑ "Welcome to the Lake Okeechobee".

- 1 2 Heather S. Henkel (2010-04-15). "SOFIA Virtual Tour - Lake Okeechobee". Sofia.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ↑ Counties of Florida map from U.S. Census Bureau.

- ↑ Hahn:11

- ↑ Hann:148

- ↑ Hanna:32

- ↑ Hann:99

- ↑ "Mosquito County, Florida, 1830 (map)". University of South Florida. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ↑ Wills, Lawrence E. (1977). A Cracker History of Okeechobee. West Palm Beach, Florida: Palm Beach County Historical Society.

- ↑ "National Hurricane Center: The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996". Nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- 1 2 3 Kleinberg, Eliot (2008-08-21). "Lake Okeechobee surpasses 12 feet for first time since January '07". Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ↑ "Polluted Muck Taken from Florida's Lake Okeechobee Prompts Fears on Land", Environmental News Network

- ↑ Lake Okeechobee Brush Fire, WINK News "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ Lizette Alvarez (September 8, 2013). "In South Florida, a Polluted Bubble Ready to Burst". The New York Times. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ↑ Hiaasen, Carl (March 13, 2016). "Where's Rick Scott in Lake O pollution crisis?". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 23A. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ↑ LaPeter Anton, Leonora; Pittman, Craig (March 19, 2016). "Lake Okeechobee flood control creates environmental disaster". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Water quality concerns grow as toxic bacteria found in Lake O". ABC 7 WZVN. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ Andy Reid (17 May 2016). "Lake Okeechobee algae bloom threatens to worsen water woes". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Florida can pay for algae recovery on its own, FEMA says". TCPalm. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ "Emergency Lake Okeechobee back-pumping granted to save wildlife". 23 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ Lodge:110

- ↑ South Florida Water Management District: Okeechobee Watershed Overview

- ↑ Reid, Andy (April 21, 2011). "Declining Lake Okeechobee water levels threaten South Florida environment, water supplies". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Brochu, Nicole Sterghos (2003). "Florida's Forgotten Storm: the Hurricane of 1928". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ↑ Lodge:105, 109

- 1 2 Fisheating Creek Sub-Watershed Feasibility Study:11

- ↑ Lodge:106

- ↑ Boning:212

- ↑ Lodge:107, 109

- ↑ Lodge:109

- ↑ "LAKE OKEECHOBEE / Water Management > Jacksonville District > Fact Sheet Article View". Jacksonville District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 2012-10-09. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "Lake Okeechobee and Florida National Scenic Trails CURRENT CLOSURES" (PDF). US Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ↑ Hurston, Zora Neale (1998). Their Eyes Were Watching God. New York: Perennial Classics. p. 129. ISBN 0-06-093141-8.

- ↑ "PBS Earth Edition- Lake Okeechobee: Big Water, Big Trouble".

References

- Boning, Charles R. (2007). Florida's Rivers. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. ISBN 978-1-56164-400-1.

- Fisheating Creek Sub-Watershed Feasibility Study - accessed 18 April 2011

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.

- Hanna, Alfred Jackson; Kathryn Abbey Hanna (1948). Lake Okeechobee. Bobbs-Merrill. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Lodge, Thomas E. (2005). The Everglades Handbook: Understanding the Ecosystem. Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 1-56670-614-9

External links

![]()