1949 Florida hurricane

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Formed | August 23, 1949 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 31, 1949 |

| (Extratropical after August 29) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 954 mbar (hPa); 28.17 inHg |

| Fatalities | 2 direct |

| Damage | $52 million (1949 USD) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Turks and Caicos Islands, Cuba, Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 1949 Atlantic hurricane season | |

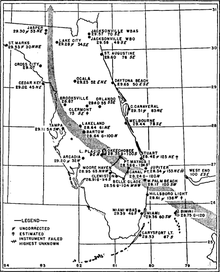

The 1949 Florida hurricane was the second recorded storm and the strongest and most intense tropical cyclone of the 1949 Atlantic hurricane season. It was the most intense tropical cyclone to affect the United States during the season, with a minimum central pressure of 954 mbar (28.18 inHg) at landfall.[1] The cyclone originated from an easterly wave near the Leeward Islands,[2] and it rapidly intensified to a hurricane near the Bahamas. It strengthened to a major hurricane northwest of Nassau, Bahamas, and it struck West Palm Beach, Florida as a Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds near 130 mph (210 km/h)[3] and peak gusts near 160 mph (260 km/h) above the surface.[4] It turned north over the Florida peninsula, and it transitioned to an extratropical low pressure area over New England. The tropical cyclone inflicted $52,000,000 (1949 USD) in damage, most of which was incurred in the state of Florida. It was the costliest storm of the season.[2]

Meteorological history

On August 23, a moderate tropical storm developed 200 miles (323 km) east of Sint Maarten.[3] Operationally, the system was treated as an easterly wave until it moved through the Bahamas.[2] It is believed that the system originated near the Cape Verde islands.[4] On August 24, the tropical storm passed north of the Leeward Islands and San Juan, Puerto Rico, and then strengthened to a minimal hurricane with 75 mph (120 km/h) winds on August 25. Subsequently, it strengthened rapidly, and the cyclone was noted as "well developed" when it passed near Nassau[2] with 115 mph (185 km/h) winds on the morning of August 26.[3] At the time, it was the equivalent of a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. The storm strengthened further over the Gulf Stream, and it moved ashore over the city of West Palm Beach as a strong Category 4 hurricane around 7:20 p.m. EDT.[2][3] The city's airport reported calm conditions from 7:20–7:40 p.m., and the minimum central pressure of 954 mbar (28.18 inHg) was measured at the site. Peak gusts were recorded at 125 mph (205 km/h) before the anemometer blew away.[4] A maximum sustained wind of 153 mph (246 km/h) was reported from the Jupiter Inlet Light station prior to the loss of the anemometer; although conditions were slightly more severe after the reading, reliable estimates are unavailable.[2] The Atlantic hurricane database lists the cyclone as a strong Category 4 hurricane at landfall.[3] The wind reading is the basis for the Category 4 designation in the Atlantic hurricane database, although a reduction from the anemometer's elevated location lends credence to the concept of a weaker system.[5] Originally, the system was designated as a Category 3 hurricane in the state of Florida, based on the minimum central pressure reading of 954 mbar (28.18 inHg); this pressure corresponds to the original classification of a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.[1][6] However, modern analysis applies Saffir-Simpson rankings based on maximum sustained wind speeds.[7] The 1949 Florida hurricane will be eventually reanalyzed by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project, which may find a weaker hurricane in Florida.[8] The central pressure of 954 mbar (28.18 inHg) is unusually high for a strong Category 4 hurricane; the reanalysis project has discovered that hurricanes erroneously featured stronger winds than the typical pressure/wind relationship in the 1940s–1960s, unlike subsequent hurricanes in the 1970s–1980s. The evidence suggests wind speeds may have been overestimated for hurricanes in the 1940s–1960s.[7]

Inland, the hurricane moved over the northern portion of Lake Okeechobee,[2] following a similar path as the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane.[4] On August 27, the hurricane recurved over the Florida peninsula, and then weakened to a Category 1 hurricane northeast of Tampa. The system diminished to a tropical storm near Cedar Key, and it entered southern Georgia during the morning of August 28.[3] The system passed over the Carolinas as a weak tropical storm,[3] and it was operationally noted as a "weak disturbance" at the time.[2] The cyclone passed through the Mid-Atlantic states and New England on August 29; it became extratropical over New Hampshire. On August 31, the extratropical low was last detected over the western North Atlantic Ocean.[3]

Preparations

On August 25, the northern Bahamas were advised to initiate hurricane precautions, and a hurricane warning was issued for the islands. South Floridians were encouraged to closely monitor the progress of the storm.[9] On August 26, hurricane warnings were released from Miami to Vero Beach; officials decided to cancel proposed evacuations of the Lake Okeechobee region, as the presence of the Herbert Hoover Dike was expected to prevent flooding.[10]

Impact

In the Bahamas, the cyclone produced 120 mph (195 km/h) wind gusts on Bimini.[2] Damages in the Bahamas are unknown.

The cyclone produced hurricane-force gusts in Florida from Miami Beach to Saint Augustine. The majority of the state experienced sustained winds of at least 50 mph (85 km/h).[4] The strongest winds were observed between northern Broward County and St. Lucie County, as well as around Lake Okeechobee. Many locations in this region of the state recorded sustained winds over 100 mph (160 km/h), while a few sites measured wind gusts of 140 mph (230 km/h) or higher. The strongest sustained wind speed at standard height was 127 mph (204 km/h) in Lake Worth,[11] while unofficial wind gusts reached 160 mph (260 km/h) at Stuart.[4] The minimum central pressure observed was 954 mbar (28.17 inHg) in West Palm Beach.[11] The cities of Jupiter, Palm Beach, Stuart, and West Palm Beach experienced the most severe damage from the storm in South Florida.[12] A damage assessment conducted in 22 counties indicated that approximately 18,000 homes suffered damage, while roughly 1,000 other structures were severely damaged or destroyed.[13] The cyclone inflicted heavy citrus losses, and one-third of the trees were uprooted in many groves. Agricultural damage reached $20 million, with about 14 million boxes of fruit lost.[14] Overall, the state suffered roughly $45 million in damage, which included $20 million in damage to crops, $18 million to property, $4 million electrical and communications, and $500,000 to road infrastructure.[11] Only two deaths occurred in Florida, which was attributed to advance warnings.[14]

In Miami, winds reached up to 54 mph (87 km/h). Impact in the city and Miami Beach was primarily limited to minor damage to signs, plants, and trees.[15] One death occurred in the city when a man drowned in Biscayne Bay while swimming to moor a small boat.[16] The strongest sustained winds speed in Fort Lauderdale was 80 mph (130 km/h), while gusts peaked at 100 mph (160 km/h).[17] Many signs, trees, and shrubbery were damaged, with a number of trees falling onto streets. A possible tornado downed several coconut palm trees onto U.S. Route 1. Several plate glass windows at downtown businesses were shattered.[18] Heavy rainfall flooded many intersections and streets in low-lying and poor drainage areas of the city.[19] The hurricane demolished three homes in Pompano Beach, while part of an apartment complex was severely damaged. Additionally, store and restaurant fronts and their roofs also suffered damage.[20] Winds toppled 15 electrical poles onto State Road 811.[17] Throughout Broward County, 150 homes were destroyed and 150 others suffered damage.[13] Communications were mostly disrupted in Boca Raton.[15] A number of homes experienced structural impacts in Delray Beach, with five homes being destroyed,[20] while many businesses received major damage. In Boynton Beach, extensive impact was incurred shrubbery, trees, and property. Several structures were deroofed. The bridge across the Intracoastal Waterway was left impassable.[15] The "negro section" of Boynton Beach suffered $10,000 in damage,[21] which included extensive damage to stores.[15]

Tides lashed the coast, with the worst impact between Lake Worth and Palm Beach. Much of the island of Palm Beach was covered with power lines, trees, broken glass, sand, and other debris. Between Joseph E. Widener's mansion in Palm Beach and the Lake Worth casino, several washouts were reported. Along State Road 704 (Royal Palm Way), many royal palm trees were toppled.[22][20] At the Society of the Four Arts, several trees were uprooted and the library garden was ruined. The radio antenna at the town hall collapsed, damaging the roof, police and firefighters barracks, the door to the fire station, and a car.[23] Palm Beach suffered approximately $2.6 million in damage.[21] In Lake Worth, a total of about 400 people stayed at six shelters in the area during the storm. Between 300 and 400 homes were impacted by the storm, with most of the effects limited to broken roofs, shattered windows, and water damage. One home was completely demolished. This does not include the number of homes deroofed in the "negro quarters". Additionally, a trailer was overturned and "rolled over and over like a rubber ball". Many plate-glass windows broke in the business district, while a filling station on State Road 802 was destroyed.[24] Three of the four radio towers in the city were toppled.[25]

In West Palm Beach, cars were overturned in the interior of a dealership as winds shattered windows.[4] At the Palm Beach International Airport, some hangars collapsed, causing 16 planes to be destroyed and 5 others to affected. Additionally, 15 C-46s suffered damage. Almost $1 million in damage occurred at the airport alone. Nearby, several warehouses which stored cars experienced roof cave-ins, crushing a number of vehicles. Several homes near the airport were deroofed.[26] A shelter was deroofed, forcing the Red Cross and National Guard to evacuate about 60 people. Another shelter suffered wind and water damage, resulting in about 200 people moving to a different part of the building.[27] A 196 ft (60 m) radio tower owned by WJNO fell into the Intracostal Water. Nearby, storm surge flooded a hotel lobby with 6 in (150 mm) of water, while winds damaged its glass dome.[15] Approximately 2,000 homes out of about 7,000 in the city were damaged. It was estimated that the hurricane caused more than $4 million in damage in West Palm Beach.[22]

Sustained winds at Belle Glade peaked at 100 mph (160 km/h) and wind gusts reached 140 mph (230 km/h) before the anemometer blew away.[11][15] A number of power lines and trees were downed, while the WSWN radio station tower fell. At the state prison, the roof of an implement shed collapsed, destroying about $50,000 worth of equipment.[15] Additionally, two barns were demolished and the dining hall, dormitories, and a parking garage were inflicted damage.[25] Damage in the city was estimated at more than $1 million.[20] Tides reached 12 ft (144 in) above normal at Belle Glade and Clewiston and the Lake Okeechobee area was lashed with winds of at least 122 mph (196 km/h) for about seven hours,[4][20] but the Herbert Hoover Dike remained intact, protecting the area from severe flooding. Minimal erosion occurred in some locales.[4] Significant damage was reported in Pahokee and communications were knocked out completely.[15] In Riviera Beach, two stores were destroyed, while about 50 businesses and 500 homes sustained damage.[25] Throughout Palm Beach County, the storm destroyed 65 homes and damaged 13,283 others.[13]

Water entered many homes in Palm Beach and Martin counties. Snakes and mosquitoes infested many residences. Precipitation totals of 8.18, 7.10, and 9.51 inches (242 mm) were measured at Belle Glade, Okeechobee, and St. Lucie Lock, respectively.[4]

About 40% of homes in Stuart and commercial structures were severely damaged, while 90% of structures required repairs. A church, baseball park, and ice company was destroyed in the area's black neighborhoods. Many flimsy buildings were destroyed in the neighborhoods.[12] Three portions of the Jensen causeway near Sewall's Point were ripped away. A hangar and beacon was destroyed at the local airport in Martin County.[28] About 500 people were homeless in Stuart.[29][30] A water mark of 8.5 ft (102 in) was recorded on the St. Lucie River near Stuart.[30] In Fort Pierce, winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) were reported.[15] Trees, electrical poles, and power lines littered the streets, with nearly the entire city losing electricity.[20] A hotel was deroofed and many businesses suffered substantial damage. Officials noted that every home suffered some degree of damage.[25] The Indian River overflowed, flooding the city with millions of gallons of water.[20] The hurricane destroyed 35 homes and damaged 3,300 others.[13] Vero Beach reported sustained winds of 97 mph (156 km/h) and peak gusts of 110 mph (177 km/h).[31] A man in was injured in Vero Beach while attempting to operate a pump in the midst of hurricane force winds; he succumbed to his injuries at a hospital in Palm Beach about two weeks later.[16]

Wind gusts of 75 mph (120 km/h) affected Clermont, and numerous central Florida communities reported severe damage from the winds.[4] The observation station at Archbold Biological Station reported peak wind gusts of 110 mph (175 km/h); the town of Sebring reported 125 mph (205 km/h) gusts, which caused damage to trees and severe structural damage to buildings. Estimations of property damage reached $100,000 in the town, and local citrus groves estimated losses near $2 million. Buildings received considerable damage in the Lake Placid area, and telegraph, telephone, rail, and bus services were disrupted.[32]

Flooding affected Georgia and the Carolinas, although the rains alleviated drought conditions in Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, and New England.[12] Charleston, South Carolina reported a wind gust of 80 mph (129 km/h), and power lines were damaged. In Maryland, damage was minimal, although trees were prostrated and electrical services were down.[33] Throughout the United States, the hurricane caused two deaths and about $52.35 million in damage.[11]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Atlantic hurricane research division (2008). "All U.S. Hurricanes (1851-2007)". NOAA. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Zoch, Richmond T (1949). "North Atlantic Hurricanes and Tropical Disturbances of 1949" (PDF). U.S. Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Atlantic hurricane research division (2008). "Atlantic hurricane best track (1851–2007)". NOAA. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Barnes, p. 183

- ↑ Norcross, Bryan (2007). Hurricane Almanac. St. Martin's Griffin.

- ↑ Jarrell, Jerry D.; et al. (1992). "Hurricane Experience Levels of Coastal County Populations from Texas to Maine" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- 1 2 Landsea, Christopher W.; et al. (2007). "A Reanalysis of the 1911–20 Atlantic Hurricane Database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. Bibcode:2008JCli...21.2138L. doi:10.1175/2007jcli1119.1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Atlantic Hurricane Research Division. "Re-Analysis Project". Archived from the original on 1 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ "South Florida Put on Alert for Hurricane". Moberly Monitor-Index. The Associated Press. August 25, 1949. Retrieved July 5, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hurricane Due to Hit Florida this Afternoon". Moberly Monitor-Index. Associated Press. August 26, 1949. Retrieved July 5, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Barnes, p. 184

- 1 2 3 4 "18,000 Homes Hit in 22-County Part Of State Raked By Storm". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. August 30, 1949. p. 1. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- 1 2 Barnes, p. 185

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Hurricane Roundup". Fort Lauderdale News. Associated Press. August 27, 1949. p. 5. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- 1 2 Grady Norton. "Florida – August 1949". Climatological Data – Florida. Miami, Florida: Weather Bureau. p. 128. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Clouds Lift As 'Big Blow' Moves Northward". Fort Lauderdale News. August 27, 1949. p. 1. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Hurricane". Fort Lauderdale News. August 27, 1949. p. 6. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ↑ Lawson E. Parker (August 27, 1949). "Wind-Driven Dirty Ocean Lashes Coast". Fort Lauderdale News. p. 1. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Towns Lashed by Hurricane Report Millions in Damage". The Palm Beach Post. August 28, 1949. p. 9. Retrieved February 28, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Fred Van Pelt (August 28, 1949). "All Agencies Aid Storm Victims". The Palm Beach Post. p. 10. Retrieved February 28, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Towns Lashed by Hurricane Report Millions in Damage". The Palm Beach Post. August 28, 1949. p. 1. Retrieved February 28, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Scattered Debris Marks Palm Beach". The Palm Beach Post. August 28, 1949. p. 10. Retrieved February 28, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Lake Worth Reports Damage is Less Than in 1947 Storm". The Palm Beach Post. August 28, 1949. p. 10. Retrieved February 28, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "Incomplete Reports Place State's Hurricane Devastation At Millions of Dollars". The Miami News. August 28, 1949. p. 2A. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Airport Damage Nears $1 Million". The Palm Beach Post. August 28, 1949. p. 10. Retrieved March 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hundreds Homeless In Wake of Blow; Destruction Heavy". Fort Lauderdale News. Associated Press. August 27, 1949. p. 1. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ↑ The Associated Press (1949). "Hurricane Batters Florida Coast". The Winona Republican-Herald. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- ↑ The Associated Press (1949). "Tropical Gale Cuts Wide Swath of Destruction Across Florida". Moberly Monitor-Index. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- 1 2 Bush et al., p. 204

- ↑ "Continued from Page One". Chester Times. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- ↑ Lohrer, Fred E. "Hurricanes at Archbold Biological Station, 1948 & 1949". Archbold Biological Station. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ The Associated Press (1949). "Big Hurricane Blows Itself Out". The Maryville Daily Forum. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

References

- Barnes, Jay (1998). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. ISBN 0-8078-2443-7.

- Bush, David M. et al. (2004). Living with Florida's Atlantic Beaches: Coastal Hazards from Amelia Island to Key West. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3251-5.