Donalsonville, Georgia

| Donalsonville, Georgia | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Donalsonville City Hall | |

| Motto(s): The Gateway to Lake Seminole[1] | |

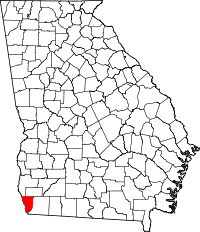

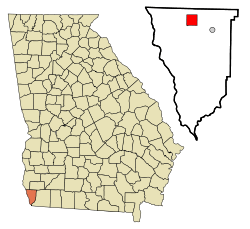

Location in Seminole County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 31°2′27″N 84°52′42″W / 31.04083°N 84.87833°WCoordinates: 31°2′27″N 84°52′42″W / 31.04083°N 84.87833°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Seminole |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Dan Ponder, Jr. (R) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4 sq mi (10.3 km2) |

| • Land | 4 sq mi (10.3 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) |

| Elevation | 148 ft (45 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 2,650 |

| • Estimate (2016)[2] | 2,637 |

| • Density | 703/sq mi (271.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 39845 |

| Area code(s) | 229 |

| FIPS code | 13-23368[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0331568[4] |

| Website | Official website |

Donalsonville is a city in Seminole County, Georgia, United States. The population was 2,796 at the 2000 census. The city is the county seat of Seminole County.[5]

History

Donalsonville was originally part of Decatur County. It is named after John Ernest Donalson (1846–1920), also known as Jonathan or John E. Donalson, a prominent businessman of the area. Donalson built the first lumber mill in Donalsonville, Donalson Lumber Company. He also built homes and a commissary for the workers of the mill. The lumber company paved the way for the town's growth.

Donalsonville was first chartered as a town in Georgia on December 8, 1897.[6] When Seminole County was formed in January 1920, Donalsonville was named as its county seat. By August 1922, the Town of Donalsonville became known as the City of Donalsonville, with the charter passing on August 19, 1922.

The Seminole County Courthouse was erected in 1922 and is still standing today. The Courthouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. (Wolfe)

Geography

Donalsonville is located at 31°2′27″N 84°52′42″W / 31.04083°N 84.87833°W.[7]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.0 square miles (10 km2), of which 4.0 square miles (10 km2) is land and 0.25% is water. The city is located 20 minutes north of Lake Seminole, 62 miles (100 km) south of Albany, 36 miles (58 km) east of Dothan, Alabama and 107 miles (172 km) west of Valdosta.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 519 | — | |

| 1910 | 747 | 43.9% | |

| 1920 | 1,031 | 38.0% | |

| 1930 | 1,183 | 14.7% | |

| 1940 | 1,718 | 45.2% | |

| 1950 | 2,569 | 49.5% | |

| 1960 | 2,621 | 2.0% | |

| 1970 | 2,907 | 10.9% | |

| 1980 | 3,320 | 14.2% | |

| 1990 | 2,761 | −16.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,796 | 1.3% | |

| 2010 | 2,650 | −5.2% | |

| Est. 2016 | 2,637 | [2] | −0.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 2,650 people residing in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 61.4% Black, 34.1% White, 0.0% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.3% from some other race and 1.2% from two or more races. 2.1% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

At the 2000 census,[3] there were 2,796 people, 1,008 households, and 697 families residing in the city. The population density was 702.8 people per square mile (271.2/km²). There were 1,116 housing units at an average density of 280.5 per square mile (108.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 37.23% White, 58.73% African American, 0.07% Native American, 0.46% Asian, 2.75% from other races, and 0.75% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.90% of the population.

There were 1,008 households of which 32.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.6% were married couples living together, 27.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.8% were non-families. 28.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.62 and the average family size was 3.23.

The age distribution was 29.3% under the age of 18, 9.4% from 18 to 24, 25.3% from 25 to 44, 18.0% from 45 to 64, and 18.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.4 males.

The median household income was $20,687, and the median family income was $25,679. Males had a median income of $24,464 versus $16,451 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,095. About 25.4% of families and 32.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 45.6% of those under age 18 and 27.6% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

According to the 2000 Census of the U.S. Census Bureau, there is a total of 2,796 people living in Donalsonville, with 45.3% males and 54.7% females. There is 58.7% African American, 37.2% Caucasians, 3.9% Hispanic, and 4.1% other races living in Donalsonville. Donalsonville has about a 63% high school graduate rate with about 52% in the work force. The biggest industries are education, health, and social services. (Georgia.gov) The average median income for households according to the U.S. Census report in 2000 was $20,687 and median family income was $25,679, with the average household size around 2 and family size around 3 people.

Employment

According to 2012 data from the Donalsonville Chamber of Commerce,[9] the top five employers in the city are as follows:

| Employer | Employees |

|---|---|

| Donalsonville Hospital, Inc. | 350 |

| Ponder Enterprises Inc. | 250 |

| Lewis M. Carter, Inc. | 150 |

| American Peanut Growers Group, LLC | 80 |

| JH Harvey Company | 30 |

Culture

Agriculture, art and music reflect the tone of the city. The Olive Theatre is in an old building downtown which has been renovated and periodically hosts local talent in addition to several plays, concerts, talent contests and other artistic events. Hand-painted murals are present on a few of the downtown buildings and depict the main industry in the county, agriculture.

The former "Harvest Festival", now "Georgia's Big Fish Festival", is a part of Donalsonville’s culture as well. This festival is held each October to educate visitors, support and promote the many sporting and recreational opportunities available at nearby Lake Seminole.

There are many other attractions that are held in and around the City as well including the Christmas Tour of Homes, the PRCA Rodeo, mug track racing, occasional street dances, outdoor concerts, movie nights, indoor concerts, karaoke, parades, book signings, and more.

Education

The Seminole County School District holds pre-school to grade twelve, and consists of one elementary school and one middle-high school.[10] The district has 120 full-time teachers and over 1,754 students.[11]

- Seminole County Elementary School

- Seminole County Middle/High School

Public Library

Donalsonville is home to the Seminole County Public Library.[12] The library serves the citizens of Donalsonville and Seminole County with a collection of print and audiovisual materials. The library is located at 103 W. 4th Street in Donalsonville.

The Alday Murders

Donalsonville was the site of the second largest mass murder in Georgia history (the largest being the Woolfolk murders in 1887). On May 14, 1973, Carl Isaacs, his half brother Wayne Coleman, and fellow prisoner George Dungee escaped from the Maryland State Prison. They were later joined by Carl's younger brother, 15-year-old Billy Isaacs.[13] While en route to Florida the men came upon the Alday farm in Donalsonville. They stopped at a mobile home owned by Jerry Alday and his wife Mary, to look for gas as there was a gas pump on the property.[14]

Alday and his father Ned Alday arrived as the trailer was being ransacked and were ordered inside, then shot to death in separate bedrooms. Jerry's brother Jimmy arrived at the trailer on a tractor and he too was led inside and forced to lay on a couch, then shot. Later, Jerry's 25-year-old wife Mary arrived at the trailer as the men attempted to hide the tractor. She was restrained, while Jerry's brother Chester and uncle Aubrey arrived in a pickup truck. The criminals accosted the pair still in their truck and forced them inside the trailer where they were also shot to death. Mary Alday was raped on her kitchen table before being taken out to a wooded area miles away where she was raped again and then finally murdered.[15]

Billy Isaacs cooperated with prosecutors and received a twenty-year sentence for armed robbery.[16] Carl Isaacs, Coleman, and Dungee were tried by jury in Seminole County in 1973, convicted, and sentenced to death. All three convictions and sentences were overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit in 1985, on the grounds that the pool of local jurors had been tainted by excess pretrial publicity.[17] All three defendants were re-tried in 1988 and were again convicted; however, only Carl Isaacs was sentenced to death, Coleman and Dungee receiving life sentences.

Carl Isaacs was executed on May 6, 2003, at Georgia Diagnostic and Classification State Prison in Jackson, by lethal injection.[18] At the time of his execution, aged 49, he was the longest-serving death row inmate anywhere in the USA, having spent 30 years on death row prior to execution.[19][20]

Billy Isaacs was released from prison in 1993,[21] but died in Florida on May 4, 2009. George Dungee died in prison on April 4, 2006. Only Wayne Coleman remains incarcerated (as of 2016).

Janice Daugharty published a fictionalized account of the murders, Going to Jackson (2010, ). The crimes were also portrayed in the 1988 film Murder One starring Henry Thomas.[22]

Religion

By the 1900s, the need for churches arose. The first church was erected in Donalsonville in 1850, the Friendship United Methodist Church. In the beginning the Methodist Church served as a meeting place for all Protestant denominations. Later, the First Presbyterian Church of Donalsonville was established in January 1898 with 25 members. On August 4, 1902, 18 people helped to create the First Baptist Church of Donalsonville. The Church of The Nazarene, originally called “The Holiness Church,” was established in October 1902. The meetings of the Church of the Nazarene were actually held in a member’s house until 1903, when a building was erected. The first black church in Donalsonville was created in 1895, the Live Oak African Methodist Episcopal Church. The people of Donalsonville saw the need to create churches to worship and with this vision came a number of churches, eventually totaling thirteen. (City-Data.com)

Notable people

- John and Clarence Anglin - brothers who escaped from Alcatraz prison in 1962 and were never seen again.

- Bacarri Rambo - Miami Dolphins safety

- Phillip Daniels - Director of Player Development

- Jaromy Henry - Author of The Bastard Boys of Montezuma and The Blood Maker and the Witch's Curse www.jaromyhenry.com

References

- ↑ ""Gateway to Lake Seminole" - Donalsonville, GA - Welcome Signs on Waymarking.com". Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 63. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Donalsonville Chamber of Commerce". Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ↑ Georgia Board of Education, Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ School Stats, Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Homepage". Southwest Georgia Regional Library System. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ Patterson, Catherine (14 July 2015). "42 years after Alday murders, no closure". DONALSONVILLE, GA: Raycom Media. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "Attorney General Baker Announces Execution of Carl Isaacs, Georgia's Longest Serving Death Row Inmate | Office of Attorney General Chris Carr". law.georgia.gov. Department of Law | State of Georgia. 6 May 2003. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ Stillman, Jack (20 May 1973). "An Ordinary Day Became a Night of Mass Murder". Associated Press (Vol. 66, No. 218). Donalsonville, GA: The Ledger. p. 16. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "'Laughed' at mercy plea | Youth accuses brother of slaughtering family". UPI. Donalsonville, GA.: Chicago Tribune. 3 January 1974.

- ↑ Schwartz, Jerry (26 January 1988). "Man Convicted Again in Killing of Georgia Family". Special To The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "Carl Junior Isaacs #852". Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "Aldays see killer executed | chronicle.augusta.com". chronicle.augusta.com. ATHENS, Ga. Morris News Service. 10 March 2003. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "Carl Isaacs Executed". todayingeorgiahistory.org/. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ Apperson, Jay (21 October 1993). "After 20 years, freedom nears Judge orders parole for Isaacs, 36, who took part in deadly '73 rampage". tribunedigital-baltimoresun. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "The movie Murder One, based on the 1973..." tribunedigital-orlandosentinel. Orlando Sentinel. 16 October 1988. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

Seminole County. Historical Society Cornerstone of Georgia Seminole County. Georgia: WH Wolfe. 1991.

U.S. Census Bureau. 13 Nov. 2007

Broome, Brenda. Phone Interview. 14 Nov. 2007

Georgia.gov. 13 Nov. 2007

City-Data.com. 14 Nov. 2007

External links

- Official Website of Donalsonville-Seminole County Chamber of Commerce Includes Donalsonville and Iron City

- Seminole County School System includes Donalsonville, Iron City and Seminole County

- Seminole County Public Library