Starkville, Mississippi

| Starkville, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| City | |

Cotton District | |

| Nickname(s): StarkVegas,[1] Boardtown[2] | |

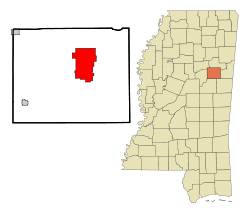

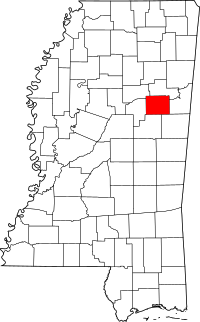

Location of Starkville, Mississippi | |

Starkville, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°27′45″N 88°49′12″W / 33.46250°N 88.82000°W | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| County | Oktibbeha |

| City | 1835 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council government |

| • Mayor | Lynn Spruill (D)[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25.8 sq mi (66.9 km2) |

| • Land | 25.7 sq mi (66.5 km2) |

| • Water | 0.2 sq mi (0.4 km2) |

| Elevation | 335 ft (102 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 23,888 |

| • Estimate (2017)[4] | 25,352 |

| • Density | 930/sq mi (360/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 39759-39760 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-70240 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0678227 |

| Website | City of Starkville |

Starkville is a city in, and the county seat of, Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, United States.[5] Mississippi State University, the state's land-grant institution and a public flagship university, is located partially in Starkville and partially in an adjacent unincorporated area. The population was 25,352 in 2017.[6] Starkville is the most populous city of the Golden Triangle region of Mississippi. The Starkville micropolitan statistical area includes all of Oktibbeha County.

The growth and development of Mississippi State in recent decades has made Starkville a marquee American college town. College students and faculty have created a ready audience for several annual art and entertainment events such as the Cotton District Arts Festival, Super Bulldog Weekend, and Bulldog Bash. The Cotton District, North America's oldest new urbanist community,[7] is an active student quarter and entertainment district located halfway between Downtown Starkville and the Mississippi State University campus.

History

The Starkville area has been inhabited for over 2100 years. Artifacts in the form of clay pot fragments and artwork dating from that time period have been found east of Starkville at the Herman Mound and Village site, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The village site can be accessed from the Indian Mound Campground. The earthwork mounds were made by early Native Americans of moundbuilder cultures as part of their religious and political cosmology.

Shortly before the American Revolutionary War period, the area was inhabited by the Choccuma (or Chakchiuma) tribe. They were annihilated about that time by a rare alliance between the Choctaw and Chickasaw peoples.[8]

The modern European-American settlement of the Starkville area was started after the Choctaw inhabitants of Oktibbeha County surrendered their claims to land in the area in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830. Most of the Native Americans of the Southeast were forced west of the Mississippi River during the 1830s and Indian Removal.

White settlers were drawn to the Starkville area because of two large springs, which Native Americans had used for thousands of years. A mill on the Big Black River southwest of town produced clapboards, giving the town its original name, Boardtown. In 1835, when Boardtown was established as the county seat of Oktibbeha County, it was renamed as Starkville in honor of Revolutionary War hero General John Stark.[9]

On May 5, 1879, two black men who had been accused of burning a barn, Nevlin Porter and Johnson Spencer, were taken from the jail by a mob of men and hung from crossties of the Mobile and Ohio railroad.[10][11]

20th century to present

In 1922, Starkville was the site of a large rally of the Ku Klux Klan.[12]

On March 21, 2006, Starkville became the first city in Mississippi to adopt a smoking ban for indoor public places, including restaurants and bars. This ordinance went into effect on May 20, 2006.[13]

Geography

Starkville is located at 33°27′45″N 88°49′12″W / 33.46250°N 88.82000°W (33.462471, −88.819990).[14]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 25.8 square miles (66.9 km²), of which 25.7 square miles (66.5 km²) is land and 0.2 square miles (0.4 km²) (0.58%) is water.

US Highway 82 and Mississippi Highways 12 and 25 are major roads through Starkville. The nearest airport with scheduled service is Golden Triangle Regional Airport (GTR). George M. Bryan Field (KSTF) serves as Starkville's general aviation airport. There are multiple privately owned airstrips in the area.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 475 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,500 | 215.8% | |

| 1890 | 1,725 | 15.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,986 | 15.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,698 | 35.9% | |

| 1920 | 2,596 | −3.8% | |

| 1930 | 3,612 | 39.1% | |

| 1940 | 4,900 | 35.7% | |

| 1950 | 7,107 | 45.0% | |

| 1960 | 9,041 | 27.2% | |

| 1970 | 11,369 | 25.7% | |

| 1980 | 16,139 | 42.0% | |

| 1990 | 18,458 | 14.4% | |

| 2000 | 21,869 | 18.5% | |

| 2010 | 23,888 | 9.2% | |

| Est. 2017 | 25,352 | [4] | 6.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] | |||

As of the census[16] of 2010, there were 23,888 people, 9,845 households, and 4,800 families residing in the city. The population density was 936.4 people per square mile (328.7/km²). There were 11,767 housing units at an average density of 396.7/sq mi (153.2/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 58.5% White, 34.06% African American, 0.2% Native American, 3.75% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.64% from other races, and 1.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 1.8% of the population.

There were 9,845 households out of which 24.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.1% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 50.1% were non-families. 32.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the city, the population was spread out with 18.8% under the age of 18, 29.7% from 18 to 24, 26.6% from 25 to 44, 15.2% from 45 to 64, and 9.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 25 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 101.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,357, and the median income for a family was $40,557. Males had a median income of $35,782 versus $23,711 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,787. About 19.1% of families and 33.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.3% of those under age 18 and 17.8% of those age 65 or over.

Religion

Starkville has more than 80 places of worship, which serve most religious traditions. Faculty, staff and students at Mississippi State University, including those from other nations, have greatly increased the city's diversity.[17] As of October 2007, approximately half (49.74%) of the residents of Starkville claim a religious affiliation; most are Christian. Of those claiming affiliation, 41.59% self-identify as Protestant, including 25% Baptist and 11% Methodist. Lower percentages identify as Catholic, Mormon, Hindu and Muslim.[18][19]

Arts and culture

Cotton District

The Cotton District is a community located in Starkville. It was the first new urbanism development in the world.[20] It was founded in 2000 by Dan Camp, who is the developer, owner and property manager of much of the area.[21] The architecture of the Cotton District has historical elements and scale, with Greek Revival mixed with Classical or Victorian. It is a compact, walkable neighborhood that contains many restaurants and bars, in addition to thousands of unique residential units.

Government and politics

Executive and legislative authority in the city of Starkville are respectively vested in a mayor and seven-member board of aldermen concurrently elected to four-year terms.[22] Since 2017 the mayor has been Lynn A. Spruill, a Democrat and the first female mayor elected in Starkville's history. Starkville has a strong-mayor government with the mayor having the power to appoint city officials and veto decisions by the board of aldermen.

Starkville is split between Mississippi House districts 38 and 43,[23] currently represented by Democrat Cheikh Taylor and Republican Rob Roberson. The city is similarly split between Mississippi Senate districts 15 and 16 represented by Republican Gary Jackson and Democrat Angela Turner-Ford. Starkville and Oktibbeha County are in the northern districts of the Mississippi Transportation Commission and Public Service Commission, represented by Republican Mike Tagert and Democrat Brandon Presley.

Starkville is in Mississippi's 3rd Congressional District represented by Congressman Gregg Harper.

Education

Public schools

In 1927, the city and the Rosenwald Foundation opened a pair of schools, the Rosenwald School and the Oktibbeha County Training School, later known as Henderson High School, for its African American residents. In 1970, integration caused the merger of these schools with the white schools.[24] Henderson was repurposed as a junior high school, and the Rosenwald School was burned to the ground.[25]

Until 2015, the City of Starkville was served by the Starkville School District (SSD) while Oktibbeha County was served by Oktibbeha County School District (OCSD). The two districts were realigned following integration in 1970 in a way that placed Starkville and majority-White, relatively affluent areas immediately outside of the city limits into SSD while the remaining portions of Oktibbeha County, which are over 90% Black, were placed into OCSD.[26] As a result of this disparity in the racial demographics of the two districts, Oktibbeha County was placed under a Federal desegregation order.[27] Previous attempts to consolidate the two districts during the 1990s and in 2010 had been unsuccessful, but following an act of the Mississippi Legislature the two were consolidated in 2015.[28] Contrary to predictions, the public schools experienced an inflow of students from private schools when the predominantly white Starkville School district merged with the predominantly black Oktibbeha schools.[29]

The schools continue to operate under a Federal desegregation order.[30]

The following schools of the Starkville Oktibbeha Consolidated School District are located in Starkville:[31]

- Sudduth Elementary (grades K-1)

- Henderson Ward Stewart Elementary (grades 2-4)

- Overstreet Elementary (grade 5)

- Armstrong Middle School (grades 6-8)

- Starkville High School (grades 9-12)

- Emerson Preschool

- Millsaps Career & Technology Center

In 2015 it was announced that SOCSD and Mississippi State University would cooperate in establishing a partnership school. The school will be for all grade 6 and 7 students in Oktibbeha County and will be located on the Mississippi State University campus. The school will serve as an instructional site for students and faculty of Mississippi State University's College of Education, and as a one-of-a-kind rural education research center.[32] Construction on the partnership school began in spring 2017 and the school is expected to open in the fall of 2019.[33]

Prior to integration, African-American students in Starkville attended the historic Henderson High School. The school was later re-purposed as Starkville School District's junior high school and is now an elementary school.[34]

Private schools

Private schools in Starkville include:

- Starkville Academy, founded 1969

- Starkville Christian School, founded 1996

Starkville Academy has been described as a segregation academy.[35] Despite fears that the consolidation of the Starkville and Oktibbeha County school districts in 2015 would lead to additional White flight to private schools, district consolidation actually resulted in decreased enrollment at area private schools as more White parents living in Oktibbeha County opted to enroll their children in the consolidated district.[36]

Libraries

The Starkville-Oktibbeha County Public Library System is headquartered at its main branch in Downtown Starkville. In addition to the local public library, the Mississippi State University Library has the largest collection in Mississippi.[37] The Mississippi State Mitchell Memorial Library also hosts the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library and the Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana.

Media

Newspapers

- The Starkville Daily News

- The Reflector (MSU Student Newspaper)

- The Starkville Dispatch (a localized edition of The Commercial Dispatch)

Radio

- WMSV (Mississippi State Radio Station)

- WMAB (Public Radio)

- WMSU

- WQJB

- WMXU

- WJZB

- WSMS

- WSSO (WSSO was Starkville's first radio station, first broadcasting in 1949 at 250W on 1230 AM)

Television

Magazines

- Town and Gown Magazine

Notable people

- Luqman Ali, musician[38]

- Dee Barton, composer[39][40]

- Cool Papa Bell, African-American baseball player; member of Baseball Hall of Fame

- Fred Bell, baseball player in the Negro Leagues; brother of Cool Papa Bell[41]

- Josh Booty, professional baseball and football player[42]

- Julio Borbon, professional baseball player

- Marquez Branson, professional football player[43]

- Harry Burgess, governor of the Panama Canal Zone, 1928–1932[44]

- Cyril Edward Cain, preacher, professor, historian; lived in Starkville[45]

- John Wilson Carpenter III, distinguished U.S. Air Force pilot and commander[46]

- Jemmye Carroll, appeared on MTV's The Real World and The Challenge

- Joe Carter, professional football player

- Hughie Critz, professional baseball player

- Sylvester Croom, first black football coach in the Southeastern Conference[47]

- Mohammad "Mo" Dakhlalla, convicted of offenses related to his attempts to join ISIS in Syria[48]

- Willie Daniel, professional football player and businessman[49]

- Kermit Davis, basketball player and coach[50]

- Al Denson, musician and Christian radio and television show host[51]

- Antuan Edwards, professional football player

- Drew Eubanks, basketball player[52]

- Rockey Felker, football player and coach[53]

- William L. Giles, former president of Mississippi State University; lived in Starkville[54]

- Scott Tracy Griffin, author, actor, and pop culture historian

- Horace Harned, politician[55]

- Helen Young Hayes, investment manager

- Kim Hill, Christian singer

- Shauntay Hinton, Miss District of Columbia USA 2002, Miss USA 2002

- Richard E. Holmes, medical doctor and one of the five young black Mississippians who pioneered the effort to desegregate the major universities of Mississippi; graduate of Henderson High School

- Bailey Howell, college and professional basketball player; lives in Starkville[56]

- Gary Jackson, served in Mississippi Senate[57]

- Paul Jackson, artist; spent childhood in Starkville[58]

- Hayes Jones, gold medalist in 110-meter hurdles at Tokyo 1964 Olympics

- Martin F. Jue, amateur radio inventor, entrepreneur; founder of MFJ Enterprises[59]

- Mark E. Keenum, president of Mississippi State University[60]

- Harlan D. Logan, Rhodes Scholar, tennis coach, magazine editor, and politician

- Ray Mabus, former Mississippi governor

- Ben McGee, professional football player[61]

- Jim McIngvale, businessman in Houston, Texas

- Shane McRae, actor

- William M. Miley, U.S. Army major general; professor of military science; lived in Starkville[62][63][64]

- Freddie Milons, college and professional football player

- Monroe Mitchell, professional baseball player

- William Bell Montgomery, agricultural publisher

- Jess Mowry, author of juvenile books

- Jasmine Murray, singer

- Travis Outlaw, professional basketball player

- Archie Pate, baseball player in the Negro leagues[65]

- Ron Polk, Olympic and college Baseball Coach.[66]

- Del Rendon, musician; lived in Starkville

- Jerry Rice, professional football player; member of NFL Hall of Fame and College Football Hall of Fame

- Dero A. Saunders, journalist and author

- Roy Vernon Scott, professor emeritus at Mississippi State University

- Jimmy G. Shoalmire, historian; lived in Starkville

- Bill Stacy, football player, mayor of Starkville[67]

- Rick Stansbury, Basketball coach[68]

- John Marshall Stone, longest-serving governor of Mississippi; second president of Mississippi State University; namesake of Stone County, Mississippi[69]

- April Sykes, professional basketball player in the Women's National Basketball Association[70]

- Amy Tuck, former Mississippi Lieutenant Governor; lives in Starkville[71][72][73]

- Latavious Williams, professional basketball player[74][75]

- Jaelyn Young, terrorist[76]

In popular culture

Pilot Charles Lindbergh, the first to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean, made a successful landing on the outskirts of Starkville in 1927 during his Guggenheim Tour.[77] He stayed overnight at a boarding house in the Maben community. Lindbergh later wrote about that landing in his autobiographical account of his barnstorming days, titled WE.

Starkville is one of several places in the United States that claims to have created Tee Ball.[78] Tee Ball was popularized in Starkville in 1961 by W.W. Littlejohn and Dr. Clyde Muse, members of the Starkville Rotarians.[79] Dr. Muse was also an educator, having been principal of Starkville High School for many years. He was a renowned baseball and basketball coach (one of his early teams won a state championship).

The town itself is called by fans the Baseball Capital of the South, having been the birthplace of National Baseball Hall of Famer Cool Papa Bell and Mississippi State University, whose Diamond Dogs have made nine trips to the NCAA Baseball College World Series in Omaha, Nebraska.

Johnny Cash was arrested for public drunkenness (though he described it as being picked up for picking flowers) in Starkville and held overnight at the city jail on May 11, 1965. This inspired his song "Starkville City Jail":

They're bound to get you,

Cause they got a curfew,

And you go to the Starkville city jail.

The song appears on the album At San Quentin.

From November 2 to 4, 2007, the Johnny Cash Flower Pickin' Festival was held in Starkville. At the festival, Cash was offered a symbolic posthumous pardon by the city. They honored Cash's life and music, and the festival was expected to become an annual event.[80] The festival was started by Robbie Ward, who said: "Johnny Cash was arrested in seven places, but he only wrote a song about one of those places."[81]

A song entitled "Starkville" appears on the Indigo Girls' 2002 album Become You.

Starkville is shown on a map of Mississippi in the film Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2007).

The Mississippi Horse Park in Starkville is a National Top 40 Rodeo Facility and is considered one of the top tourist attractions in North Mississippi.

The Magnolia Independent Film Festival is held annually in Starkville in February. It is the oldest festival in the state for independent films.

The annual Cotton District Arts Festival, held in the Cotton District on the third weekend of April, is considered to be one of the top arts festivals in the state, drawing a record crowd of nearly 25,000 in 2008. On hand for the festivities were Y'all Magazine, Southern Living, Peavey Electronics, over 100 of the state's top artisans, and 25 live bands.

Starkville is home of Bulldog Bash, Mississippi's largest open-air free concert.

Located on the MSU campus, the Cullis and Gladys Wade Clock Museum has an extensive collection of mostly American clocks and watches dating to the early 18th century. The collection of over 400 clocks is the only one of its size in the region.

Starkville is mentioned in the NBC drama series, The West Wing, which aired from 1999 to 2006. Toby discusses an appropriations bill, noting that it includes 1.7 million dollars for manure handling in Starkville, Mississippi.[82]

References

- ↑ Low, Chris (August 15, 2008). "Welcome to Stark-Vegas". ESPN College Football. ESPN. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "What's in a name?" (PDF). Msucares.com. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Starkville, MS - Official Website". Cityofstarkville.org. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Community Facts". factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "The Town Paper: New Towns -- Cotton District, Mississippi". www.tndtownpaper.com. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ Galloway, Patricia. "Chakchiuma". In Sturtevant, William C. Handbook of North American Indians, V. 14, Southeast. The Smithsonian Institution. pp. 496–498. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- ↑ "Starkville's History". Archived from the original on May 24, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ↑ "Negroes Lynched". The Pascagoula Democrat-Star. May 16, 1879. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Barn Burners Lynched". Daily Globe. May 6, 1879. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ "The Parade of the Ku Klux". December 1, 1922. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Ordinance Number 2006-02" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 22, 2006. Retrieved September 5, 2006.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Community Involvement". Cityofstarkville.org. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Starkville, Mississippi (MS) religion resources - Sperling's BestPlaces". Bestplaces.net. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Starkville, Mississippi (MS) religion resources - Sperling's BestPlaces". Bestplaces.net. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ Miller (January 2002). "New Towns -- Cotton District, Mississippi". The Town Paper. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ↑ "'Community Visionary' Continues Shaking Up Starkville". Mississippi Business Journal. July 31, 2000.

- ↑ "City Government | Starkville, MS - Official Website". www.cityofstarkville.org. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Overview of State House District 38, Mississippi (State House District) - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ Bolton, Charles C. (2005). The Hardest Deal of All: The Battle Over School Integration in Mississippi, 1870-1980. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 212. ISBN 9781934110744.

- ↑ "Segregated Education". Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ "What happens when two separate and unequal school districts merge? - The Hechinger Report". The Hechinger Report. October 3, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Segregation Now". ProPublica. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ School District Consolidation in Mississippi. Mississippi Professional Educators. December 2016.

- ↑ Grant, Richard (July 19, 2016). "Starkville school merger: What went right?". Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ↑ Larson, Jeff; Hannah-Jones, Nikole (May 1, 2014). "School Segregation After Brown". Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ "The Schools of the Starkville Oktibbeha School District". www.starkvillesd.com. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ Team, ITS Web Development (May 17, 2017). "MSU, SOSD move education forward with Partnership School groundbreaking". Mississippi State University. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Work officially begins on Partnership School | Starkville Daily News". starkvilledailynews.com. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Segregated Education | A Shaky Truce : Starkville Civil Rights, 1960-1980". starkvillecivilrights.msstate.edu. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Segregated Education". Mississippi State University library project on Starkville civil rights. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ "Starkville school merger: What went right? | Mississippi Today". mississippitoday.org. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Library Overview » Mississippi State University Libraries". lib.msstate.edu. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Luqman Ali". Discogs. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Dee Barton, Mississippi jazz musician and composer from Houston and Starkville". Mswritersandmusicians.com. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Dee Barton - Biography & History - AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Fred Bell". Baseball Reference. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ Inc., Baseball Almanac,. "Josh Booty Baseball Stats by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Marquez Branson". NFL Enterprises. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Harry Burgress". Panama Canal Authority. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ Lloyd, James B. (ed). 1981. Lives of Mississippi Authors, 1817-1967. The University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi.

- ↑ "Lieutenant General John W. Carpenter III". Lanbob. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Stuart Davis Construction". Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ↑ Green, Emma (May 1, 2017). "How Two Mississippi College Students Fell in Love and Decided to Join a Terrorist Group". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Willie Daniel". Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ↑ Pogue, Greg (March 1, 2015). "Pogue: Hoops is family affair for Davis family". Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ↑ Powell, Mark Allan (2002). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Christian Music. Hendrickson Publishers.

- ↑ Moran, Danny (2 December 2016). "https://www.oregonlive.com/beavers/index.ssf/2016/12/oregon_state_kicks_off_last_no.html". Oregon Live. Retrieved 10 September 2018. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "Rockey & Susan Felker: It's All Been Good". Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ↑ Team, ITS Web Development. "W.L. Giles Biography - The W.L. Giles Distinguished Professors - Mississippi State University". Giles.msstate.edu. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ http://oktibbehaheritagemuseum.com/wordpress/2015/06/horace-harned-jr-and-the-famed-flying-tigers/

- ↑ "Bailey Howell's Mom Absolutely Knew Best". Southeastern Conference. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Gary Jackson's Biography". Votesmart. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Paul Jackson Show Opens". Boone County Museum and Galleries. June 19, 2013. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Nine named BCoE Distinguished Alumni Fellows". Mississippi State University. March 31, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ↑ Walker Geuder, Meridith (Fall 2008). "Back Home Again" (PDF). Mississippi State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Ben McGee". databaseSports.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "SB2888 (As Sent to Governor) - 1998 Regular Session". Billstatus.ls.state.ms.us. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "William "Bud" Miley". 17th-airborne.eu. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Hagerman, Bart (January 1, 1999). "Seventeenth Airborne Division". Turner Publishing Company. Retrieved March 20, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Archie Pate". Negro Leagues Database. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Times Daily - Google News Archive Search". Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Billy McGovern Stacy". Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame & Museum. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ↑ "Mississippi State's Rick Stansbury on retirement: 'I'm ready to become a better father'". Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 9, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- ↑ "April Sykes Looks to Help USA Defend Pan American Games Gold". Rutgers University. September 27, 2011. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Friends of Mississippi Veterans". Starkvilledailynews.com. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "GSDP to nominate new board members". Cdispatch.com. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Williams Ponders Next Move". Starkville Daily News. July 25, 2012. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Amy Tuck in Starkville, MS - (662) 320-8504, 6623208504 - 411". Starkvilledailynews.com. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Fausset, Richard (August 14, 2015). "Young Mississippi Couple Linked to ISIS, Perplexing All". Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Guggenheim Tour". Charleslindbergh.com. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Tee Ball". Warsaw Youth Sports. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Club History". Starkville Rotary Club. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Mississippi town to honor the 'Man in Black' - US and Canada - MSNBC.com". Msnbc.msn.com. September 6, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times "Facts Mix With Legend on the Road to Redemption." Barry, Dan. Oct.20, 2008.

- ↑ "Search or Browse The West Wing Transcripts -- View or Search transcripts and summaries". Westwingtranscripts.com. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Starkville, Mississippi. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Starkville. |

.svg.png)