St. Augustine, Florida

| St. Augustine San Agustín (Spanish) | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Saint Augustine | ||

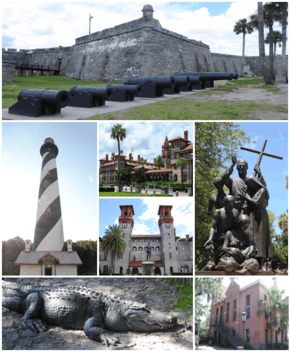

Top, left to right: Castillo de San Marcos, St. Augustine Light, Flagler College, Lightner Museum, statue near the Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine, St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, Old St. Johns County Jail | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Ancient City, Old City | ||

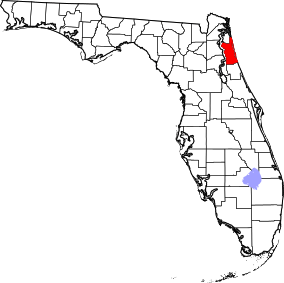

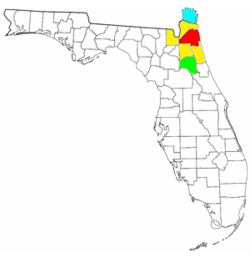

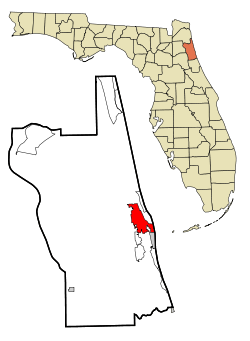

Location in St. Johns County and the U.S. state of Florida | ||

St. Augustine St. Augustine | ||

| Coordinates: 29°53′41″N 81°18′52″W / 29.89472°N 81.31444°WCoordinates: 29°53′41″N 81°18′52″W / 29.89472°N 81.31444°W[1] | ||

| Country |

| |

| State |

| |

| County |

| |

| Established |

September 8, 1565, 453 years ago | |

| Founded by | Pedro Menéndez de Avilés | |

| Named for | Saint Augustine of Hippo | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Commission–Manager | |

| • Mayor | Nancy Shaver (NP) | |

| Area[2] | ||

| • City | 12.76 sq mi (33.06 km2) | |

| • Land | 9.43 sq mi (24.43 km2) | |

| • Water | 3.33 sq mi (8.63 km2) | |

| Elevation[3] | 0 ft (0 m) | |

| Population (2016)[4] | ||

| • City | 14,280 | |

| • Estimate (2016)[5] | 14,280 | |

| • Density | 1,513.99/sq mi (584.55/km2) | |

| • Urban | 69,173 (US: 399th) | |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) | |

| ZIP code(s) | 32080, 32084, 32085, 32086, 32095, 32082, 32092 | |

| Area code(s) | 904 | |

| FIPS code | 12-62500[6] | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0308101[3] | |

| Website | City of St. Augustine | |

St. Augustine (Spanish: San Agustín) is a city in the Southeastern United States, on the Atlantic coast of northeastern Florida. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorers, it is the oldest continuously inhabited European-established settlement within the borders of the continental United States.[7]

The county seat of St. Johns County,[8] St. Augustine is part of Florida's First Coast region and the Jacksonville metropolitan area. According to the 2010 census, the city's population was 12,975. The United States Census Bureau's 2013 estimate of the city's population was 13,679, while the urban area had a population of 71,379 in 2012.[9]

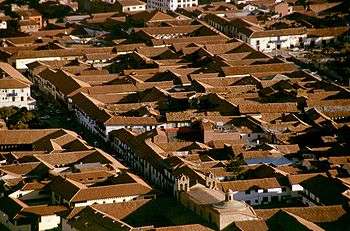

St. Augustine was founded on September 8, 1565, by Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Florida's first governor. He named the settlement "San Agustín", as his ships bearing settlers, troops, and supplies from Spain had first sighted land in Florida eleven days earlier on August 28, the feast day of St. Augustine.[10] The city served as the capital of Spanish Florida for over 200 years. It was designated as the capital of British East Florida when the colony was established in 1763 until it was ceded to Spain in 1783.

Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1819, and St. Augustine was designated the capital of the Florida Territory upon ratification of the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1821. The Florida National Guard made the city its headquarters that same year. The territorial government moved and made Tallahassee the capital in 1824. Since the late 19th century, St. Augustine's distinct historical character has made the city a major tourist attraction.

History

Founding by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Founded in 1565 by the Spanish conquistador Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, St. Augustine is the oldest continuously occupied settlement of European origin in the contiguous United States. In 1562, a group of Huguenots led by Jean Ribault arrived in Spanish Florida to establish a colony in the territory claimed by Spain. They explored the mouth of the St. Johns River, calling it la Rivière de Mai (the River May), then sailed northward and established a settlement called Charlesfort at Port Royal Sound in present-day South Carolina. Spain learned of this French expedition through its spies at ports on the Atlantic coast of France. The Huguenot nobleman René de Laudonnière, who had participated in the expedition, returned to Florida in 1564 with three ships and 300 Huguenot colonists. He arrived at the mouth of the River May on June 22, 1564, sailed up it a few miles, and founded Fort Caroline.

Desiring to protect its claimed territories in North America against such incursions, the Spanish Crown issued an asiento to Menéndez, signed by King Philip II on March 20, 1565, granting him expansive trade privileges, the power to distribute lands, and licenses to sell 500 slaves, as well as various titles, including that of adelantado of Florida.[11] This contract directed Menéndez to sail for La Florida, reconnoitre it from the Florida Keys to present-day Canada, and report on its coastal features, with a view to establishing a permanent settlement for the defense of the Spanish treasure fleet. He was ordered as well to drive away any intruders who were not subjects of the Spanish crown.[12]

On July 28, Menéndez set sail from Cádiz with a fleet led by his 600-ton flagship, the San Pelayo, accompanied by several smaller ships, and carrying over 1,000 sailors, soldiers, and settlers.[13] On the feast day of St. Augustine, August 28, the fleet sighted land and anchored off the north inlet of the tidal channel the French called the River of Dolphins.[14] Menéndez then sailed north and confronted Ribault's fleet outside the bar of the River May in a brief skirmish. On September 6, he returned to the site of his first landfall, naming it after the Catholic saint, disembarked his troops, and quickly constructed fortifications to protect his people and supplies.[15][16]

Menéndez then marched his soldiers overland for a surprise attack on Fort Caroline, where they killed almost everyone in the fort except for the women and children. Jean Ribault had already put out to sea with his ships for an assault on St. Augustine, but was surprised by a storm that wrecked his ships further south. Informed by his Indian allies that the survivors were walking northward on the coast, Menéndez began to search for the Frenchmen, who had made it as far as the banks of the Matanzas River's south entrance.[17] There they were confronted by the Spaniard and his men on the opposite side. After several parleys with the Spanish, Jean Ribault and the Frenchmen with him (between 150–350, sources differ) surrendered; almost all of them were executed in the dunes near the inlet, thereafter called Matanzas (Spanish for "slaughters").[18]

In May 1566, as relations with the neighboring Timucua Indians deteriorated, Menéndez moved the Spanish settlement to a more defensible position on the north end of the barrier island between the mainland and the sea, and built a wooden fort there. In 1572, the settlement was relocated to the mainland, in the area just south of the future town plaza. Confident that he had fulfilled the primary conditions of his contract with the King, including the building of forts along the coast of La Florida, Menéndez returned to Spain in 1567. After several more transatlantic crossings, Menéndez fell ill and died on September 17, 1574.[19]

Invasions by pirates and enemies of Spain

Succeeding governors of the province maintained a peaceful coexistence with the local Native Americans, allowing the isolated outpost of St. Augustine some stability for a few years. On May 28 and 29, 1586, soon after the Anglo-Spanish War began between England and Spain, the English privateer Sir Francis Drake sacked and burned St. Augustine.[20] The approach of his large fleet obliged Governor Pedro Menéndez Márquez and the townspeople to flee for their safety. When the English got ashore, they seized some artillery pieces and a royal strongbox containing gold ducats, the garrison payroll.[21] The killing of their sergeant major by the Spanish rearguard caused Drake to order the town burnt.[22][23]

In 1609 and 1611, expeditions were sent out from St. Augustine against the English colony at Jamestown, Virginia.[24] In the second half of the 17th century, unsettled groups of Indians, forced southward by the expanding English colony in Carolina, made raids into Florida and killed the Franciscan priests who served at the Catholic missions. Requests by successive governors of the province to strengthen the presidio’s garrison and fortifications were ignored by the Spanish Crown. The charter of 1663 for the new Province of Carolina, issued by King Charles II of England, was revised in 1665, claiming lands as far southward as 29 degrees north latitude, about 65 miles south of the existing settlement at St. Augustine.[25][26]

The English buccaneer Robert Searle then sacked St. Augustine in 1668, killing sixty people and pillaging government buildings, churches and houses,[27] after which his pirates ransomed off some of their hostages and sold others into slavery. This raid and the establishment of the English settlement at Charles Town spurred the Spanish monarchy to finally acknowledge the threat represented by the new English colonies to the north and strengthen the city's defenses. In 1669, Queen Regent Mariana ordered the Viceroy of New Spain to disburse funds for the construction of a permanent masonry fortress, which began in 1672.[28] Before the fortress was completed, buccaneers Michel de Grammont and Nicolas Brigaut planned an attack in 1686 which was foiled: their ships were run aground, Grammont and his crew were lost, and Brigaut was captured ashore by Spanish soldiers.[29] The Castillo de San Marcos was completed in 1695, not long before an attack by Governor Moore's forces from Carolina in November, 1702. Failing to take the fort after a siege of 58 days, the British troops burned St. Augustine to the ground as they retreated.[30] In 1740, the town was again besieged, this time by the governor of the British colony of Georgia, General James Oglethorpe, who was also unable to take the fort.[31]

Loyalist haven under British rule

The Treaty of Paris (1763), signed after Great Britain's victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years' War, ceded Florida to Great Britain and consequently St. Augustine became a Loyalist haven during the American Revolutionary War.[32] The second Treaty of Paris (1783), which recognized the independence of the former British colonies north of Florida, also ceded Florida back to Spain, and as a result many of the town's Spanish citizens returned to St Augustine. Refugees from Dr. Andrew Turnbull's troubled colony in New Smyrna had fled to St. Augustine in 1777, and made up the majority of the city's population during British rule. This group was, and still is, referred to locally as "Menorcans", even though it also included settlers from Italy, Corsica and the Greek islands as well.[33][34]

Second Spanish period

During the Second Spanish period (1784-1821) of Florida, Spain was dealing with invasions of the Iberian peninsula by Napoleon's armies in the Peninsular War, and struggled to maintain a tenuous hold on its territories in the western hemisphere as revolution swept South America. The royal administration of Florida was neglected, as the province had long been regarded as an unprofitable backwater by the Crown. The United States, however, considered Florida vital to its political and military interests as it expanded its territory in North America, and maneuvered by sometimes clandestine means to acquire it.[35] The Adams–Onís Treaty, negotiated in 1819 and ratified in 1821, ceded Florida and St. Augustine, still its capital at the time, to the United States.[36]

Territory of Florida

Florida remained an organized territory of the United States until 1845, when it was admitted into the Union as the State of Florida.[37] The Territorial Period (1821-1845) was marked by protracted wars with the Creek Indian groups who occupied the peninsula, collectively known as "Seminoles", during the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). The United States Army took command of the Castillo de San Marcos and renamed it Fort Marion after General Francis Marion, who fought in the American Revolutionary War. The capital of the territory was moved to Tallahassee in 1824.

Civil War

Florida joined the Confederacy after the Civil War began in 1861, and Confederate authorities remained in control of St. Augustine for fourteen months, although it was barely defended. The Union conducted a blockade of shipping. In 1862 Union troops gained control of St. Augustine and controlled it through the rest of the war. With the economy already suffering, many residents fled.[38][39]

Henry Flagler and the railroad

Henry Flagler, a co-founder with John D. Rockefeller of the Standard Oil Company, spent the winter of 1883 in St. Augustine and found the city charming, but considered its hotels and transportation systems inadequate.[40] He had the idea to make St. Augustine a winter resort for wealthy Americans from the north, and to bring them south he bought several short line railroads and combined these in 1885 to form the Florida East Coast Railway. He built a railroad bridge over the St. Johns River in 1888, opening up the Atlantic coast of Florida to development.[41][42]

Flagler began construction in 1887 on two large ornate hotels in the city, the 540-room Ponce de Leon Hotel and the 250-room Hotel Alcazar. The next year, he purchased the Casa Monica Hotel across the street from both the Alcazar and the Ponce de Leon. His chosen architectural firm, Carrère and Hastings, radically altered the appearance of St. Augustine with these hotels, giving it a skyline and beginning an architectural trend in the state characterized by the use of the Moorish Revival style. With the opening of the Ponce de Leon in 1888, St. Augustine became the winter resort of American high society for a few years.[43]

When Flagler's Florida East Coast Railroad was extended southward to Palm Beach and then Miami in the early 20th Century, the rich mostly abandoned St. Augustine. Wealthy vacationers began to customarily spend their winters in South Florida, where the climate was warmer and freezes were rare. St. Augustine nevertheless still attracted tourists, and eventually became a destination for families traveling in automobiles as new highways were built and Americans took to the road for annual summer vacations. The tourist industry soon became the dominant sector of the local economy.[44]

Civil Rights movement

In late 1963, nearly a decade after the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of schools was unconstitutional, African Americans were still trying to get St. Augustine to integrate the public schools in the city. They were also trying to integrate public accommodations, such as lunch counters,[45] and were met with arrests[46] and Ku Klux Klan violence.[47][48] Local college students held non-violent protests throughout the city, including sit-ins at the local Woolworth's, picket lines, and marches through the downtown. These protests were often met with police violence. Homes of African Americans were firebombed,[49] black leaders were assaulted and threatened with death, and others were fired from their jobs.

In the spring of 1964, St. Augustine civil rights leader Robert Hayling[50] asked the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and its leader Martin Luther King, Jr. for assistance.[51] From May until July 1964, King and Hayling, along with Andrew Young, organized marches, sit-ins, and other forms of peaceful protest in St. Augustine. Hundreds of black and white civil rights supporters were arrested,[52] and the jails were filled to capacity.[53] At the request of Hayling and King, white civil rights supporters from the North, including students, clergy, and well-known public figures, came to St. Augustine and were arrested together with Southern activists.[54][55][56]

St. Augustine was the only place in Florida where King was arrested; his arrest there occurred on June 11, 1964, on the steps of the Monson Motor Lodge's restaurant. The demonstrations came to a climax when a group of black and white protesters jumped into the hotel's segregated swimming pool. In response to the protest, James Brock, the manager of the hotel and the president of the Florida Hotel & Motel Association, poured what he claimed to be muriatic acid into the pool to burn the protesters. Photographs of this, and of a policeman jumping into the pool to arrest the protesters, were broadcast around the world.

The Ku Klux Klan responded to these protests with violent attacks that were widely reported in national and international media.[57] Popular revulsion against the Klan and police violence in St. Augustine generated national sympathy for the black protesters and became a key factor in Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[58] leading eventually to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[59] both of which provided federal enforcement of constitutional rights.

Modern St. Augustine

In 1965, St. Augustine celebrated the 400th anniversary of its founding,[60] and jointly with the State of Florida, inaugurated a program to restore part of the colonial city. The Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board was formed to reconstruct more than thirty-six buildings to their historical appearance, which was completed within a few years. When the State of Florida abolished the Board in 1997, the City of St. Augustine assumed control of the reconstructed buildings, as well as other historic properties including the Government House. In 2010, the city transferred control of the historic buildings to the University of Florida.

In 2015, St. Augustine celebrated the 450th anniversary of its founding with a four-day long festival and a visit from Felipe VI of Spain and Queen Letizia of Spain.[61]

On October 7, 2016 Hurricane Matthew caused widespread flooding in downtown St. Augustine.[62]

Geography and climate

St. Augustine is located at 29°53′41″N 81°18′52″W / 29.89472°N 81.31444°W (29.8946910, −81.3145170).[1] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.7 square miles (27.8 km2), 8.4 square miles (21.7 km2) of which is land and 2.4 square miles (6.1 km2) (21.99%) is water. Access to the Atlantic Ocean is via the St. Augustine Inlet of the Matanzas River.

St. Augustine has a humid subtropical climate or Cfa – typical of the Gulf and South Atlantic states. The low latitude and coastal location give the city a mostly warm and sunny climate. Like much of Florida, St. Augustine enjoys a high number of sunny days, averaging 2,900 hours annually. Unlike much of the contiguous United States, St. Augustine’s driest time of year is winter. The hot and wet season extends from May through October, while the cool and dry season extends November through April.

In the hot season, average daytime highs are in the upper 80s to low 90s °F (26° to 33 °C) and average night-time lows are in the low 70s °F (21 °C). The Bermuda High pumps in hot and unstable tropical air from the Bahamas and Gulf of Mexico, which help create the daily thundershowers that are typical in summer months. Intense but very brief downpours are common in mid-summer in the city. Fall and spring are warm and sunny with highs in the 75 to 80 F (21 to 24 °C) range and overnight lows in the 50s to low 60s (10 to 17 °C).

In the dry winter season, St. Augustine has generally mild and sunny weather typical of the Florida peninsula. The coolest months are from December through February, with average daytime highs that range from 65 to 70 °F (18 to 21 °C) and nighttime lows in the 46-49 F (8 to 10 °C) range. From November through April, St. Augustine often has long periods of rainless weather. Early spring (April) can see near drought conditions with brush fires and water restrictions in place. St. Augustine averages six frosts per year. Hurricanes occasionally impact the region; however, like most areas prone to such storms, St. Augustine rarely suffers a direct hit by a major hurricane. The last direct hit by a major hurricane to the city was Hurricane Dora in 1964. Extensive flooding occurred in the downtown area of St. Augustine when Hurricane Matthew passed east of the city in October 2016.[63]

| Climate data for St. Augustine | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 87 (31) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

100 (38) |

98 (37) |

92 (33) |

89 (32) |

104 (40) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

69 (21) |

73 (23) |

78 (26) |

84 (29) |

88 (31) |

90 (32) |

89 (32) |

86 (30) |

81 (27) |

74 (23) |

68 (20) |

79 (26) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 46 (8) |

49 (9) |

53 (12) |

58 (14) |

65 (18) |

71 (22) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

71 (22) |

65 (18) |

56 (13) |

49 (9) |

61 (16) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 10 (−12) |

18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

52 (11) |

58 (14) |

59 (15) |

51 (11) |

31 (−1) |

25 (−4) |

16 (−9) |

10 (−12) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.7 (69) |

3.1 (79) |

3.9 (99) |

2.6 (66) |

3.1 (79) |

5.6 (142) |

5.7 (145) |

6.5 (165) |

7.5 (191) |

4.6 (117) |

2.3 (58) |

2.4 (61) |

49.49 (1,257) |

| Source: [64] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 1,708 | — | |

| 1840 | 2,450 | 43.4% | |

| 1850 | 1,934 | −21.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,914 | −1.0% | |

| 1870 | 1,717 | −10.3% | |

| 1880 | 2,293 | 33.5% | |

| 1890 | 4,742 | 106.8% | |

| 1900 | 4,272 | −9.9% | |

| 1910 | 5,494 | 28.6% | |

| 1920 | 6,192 | 12.7% | |

| 1930 | 12,111 | 95.6% | |

| 1940 | 12,090 | −0.2% | |

| 1950 | 13,555 | 12.1% | |

| 1960 | 14,734 | 8.7% | |

| 1970 | 12,352 | −16.2% | |

| 1980 | 11,985 | −3.0% | |

| 1990 | 11,692 | −2.4% | |

| 2000 | 11,592 | −0.9% | |

| 2010 | 12,975 | 11.9% | |

| Est. 2016 | 14,280 | [5] | 10.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[65] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 12,975 people, 5,743 households, and 2,679 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,376.2 people per square mile (531/km²). There were 6,978 housing units at an average density of 549.4 per square mile (211.4/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 84.2% Caucasian, 11.6% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.8% from other races, and 1.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.1% of the population.

There were 5,743 households out of which 14.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.7% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 53.4% were non-families. 37.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.03 and the average family size was 2.67.

In the city, the population was spread out with 13.1% under the age of 18, 15.3% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 25.2% from 45 to 64, and 19% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $36,424, and the median income for a family was $56,055. Males had a median income of $32,409 versus $30,188 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,485. About 7.6% of families and 21.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.8% of those under age 18 and 24.4% of those age 65 or over.

Transportation

Highways

Buses

Bus service is operated by the Sunshine Bus Company. Buses operate mainly between shopping centers across town, but a few go to Hastings and Jacksonville, where one can connect to JTA for additional service across Jacksonville.

Airport

St. Augustine has one public airport 4 miles (6.4 km) north of the downtown. It has three runways and two seaplane lanes.[66] ViaAir provides seasonal service to Charlotte, and Elite Airways will soon provide service to Rochester, Minnesota.[67] Various private jets and tour helicopters also operate from the airport. Northrop Grumman runs a large manufacturing plant on the grounds, where the E-2 Hawkeye is produced. Jacksonville International Airport is 40 miles to the north along I-95.

Points of interest

First and second Spanish eras

- Avero House

- Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

- Fort Matanzas National Monument

- Fort Mose Historic State Park

- Nombre de Dios

- Gonzalez-Alvarez House

- Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park

- The Spanish Military Hospital Museum

- St. Francis Barracks

- Colonial Quarter

- Ximenez-Fatio House

- González-Jones House

- Llambias House

- Oldest Wooden Schoolhouse

- Tolomato Cemetery and Huguenot Cemetery

British era

Pre-Flagler era

- St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum

- Markland Mansion

Flagler era

- Ponce de Leon Hotel

- Casa Monica Hotel

- Hotel Alcazar

- Zorayda Castle

- Bridge of Lions

- Old St. Johns County Jail

- Ripley's Believe it or Not! Museum located in 1887 mansion of William Worden.

- St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park

Historic churches

Lincolnville National Historic District – Civil Rights era

Other points of interest

Sister cities

- Laayoune, Western Sahara

Education

Primary and secondary education in St. Augustine is overseen by the St. Johns County School District. There are no county high schools located within St. Augustine's current city limits, but St. Augustine High School, Pedro Menendez High School, and St. Johns Technical High School are located in the vicinity. The Florida School for the Deaf and Blind, a state-operated boarding school for deaf and blind students, was founded in the city in 1885.[68] The Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine operates the St. Joseph Academy, Florida's oldest Catholic high school, to the west of the city.[69]

There are several institutions of higher education in and around St. Augustine. Flagler College is a four-year liberal arts college founded in 1968. It is located in the former Ponce de Leon Hotel in downtown St. Augustine.[70] St. Johns River State College, a state college in the Florida College System, has its St. Augustine campus just west of the city. Also in the area are the University of North Florida, Jacksonville University, and Florida State College at Jacksonville in Jacksonville.[71]

The institution now known as Florida Memorial University was located in St. Augustine from 1918 to 1968, when it relocated to its present campus in Miami. Originally known as Florida Baptist Academy, then Florida Normal, and then Florida Memorial College, it was a historically black institution and had a wide impact on St. Augustine while it was located there. During World War II it was chosen as the site for training the first blacks in the U. S. Signal Corps. Among its faculty members was Zora Neale Hurston; a historic marker is placed at the house where she lived while teaching at Florida Memorial[72] (and where she wrote her autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road.)[73][74]

Notable people

- Jim Albrecht, poker tournament director and commentator

- Andrew Anderson, physician, St. Augustine mayor

- John Alexander Armstrong, political theorist and scholar

- Murray Armstrong, hockey coach

- Pete Banaszak, professional football player[75]

- Frances Bemis, public relations specialist

- Jorge Biassou, Haitian revolutionary and first black American general

- Richard Boone, actor

- James Branch Cabell, novelist

- Doug Carn, jazz musician

- Cris Carpenter, Major League baseball player

- Ray Charles, pianist, singer, composer

- George J. F. Clarke, Surveyor General of Spanish East Florida

- Nicholas de Concepcion, escaped slave who became a Spanish privateer and pirate captain

- Earl Cunningham, artist

- Alexander Darnes, born a slave, became a celebrated physician

- Edmund Jackson Davis, governor of Texas

- Frederick Delius, composer

- Henry Flagler, industrialist

- Willie Galimore, football player

- Michael Gannon, historian

- Laura Jane Grace, singer

- William H. Gray, U. S. congressman and president of the United Negro College Fund

- Robert Hayling, civil rights leader

- Hurley Haywood endurance race car driver[76]

- Martin Johnson Heade, artist

- Louise Homer, opera singer

- Sidney Homer, composer

- Jack D. Hunter, novelist, author of The Blue Max

- Zora Neale Hurston, novelist and folklorist

- Lindy Infante, professional football coach

- Willie Irvin, professional football player

- Brandon James, professional football player

- Stetson Kennedy, author and human rights activist

- Jack Temple Kirby, historian

- LaChanze, Tony Award & Emmy Award winning actor, singer, and dancer

- Scott Lagasse Jr., race car driver

- Charlie LaPradd, college football player, college president

- Jacob Lawrence, artist

- Sinclair Lewis, novelist

- John C. Lilly, neuroscientist, developer of the isolation tank

- William W. Loring, Confederate general

- Mary MacLane, author

- Albert Manucy, historian, author, Fulbright Scholar

- George McGovern, U.S. Senator, presidential candidate

- Howell W. Melton, United States district judge

- Howell W. Melton Jr., attorney, law firm managing partner

- Johnny Mize, Hall of Fame baseball player

- Prince Achille Murat, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte

- David Nolan, author and historian

- Ashley Ann Olsen, murder victim

- Osceola, Seminole War leader (held prisoner at Fort Marion, now Castillo de San Marcos)

- Tom Petty, rock musician

- Scott Player, professional football punter

- Verle A. Pope, state legislator

- Richard Henry Pratt, soldier and educator

- Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, novelist

- Marcus Roberts, musician

- Gamble Rogers, folksinger

- John M. Schofield, Union general

- Steven L. Sears, television writer-producer

- Sheamus, Irish professional wrestler

- Edmund Kirby Smith, Confederate general

- Steve Spurrier, college/pro (American) football coach

- Caleb Sturgis, NFL kicker

- Peter Taylor, novelist

- Travis Tomko, professional wrestler

- The Wobbly Toms, music group

- Felix Varela, Cuban national hero

- Augustin Verot, first Bishop of St. Augustine

- Patty Wagstaff, aerobatic pilot

- DeWitt Webb, physician, St. Augustine mayor, state representative

- David Levy Yulee, first Jewish U.S. Senator, Levy County and Yulee, Florida namesake

Gallery

.jpg) Bell tower on northeast bastion of the Castillo de San Marcos

Bell tower on northeast bastion of the Castillo de San Marcos.jpg) North bastions and wall of the Castillo, looking eastward toward Anastasia Island

North bastions and wall of the Castillo, looking eastward toward Anastasia Island.jpg) Seawall south of the Castillo

Seawall south of the Castillo The city gates of St. Augustine, built in 1808, part of the much older Cubo Line

The city gates of St. Augustine, built in 1808, part of the much older Cubo Line The Government House. East wing of the building dates to the 18th-century structure built on original site of the colonial governor's residence.[77]

The Government House. East wing of the building dates to the 18th-century structure built on original site of the colonial governor's residence.[77].jpg) Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Augustine

Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Augustine Shrine of Our Lady of La Leche at Mission Nombre de Dios

Shrine of Our Lady of La Leche at Mission Nombre de Dios-Juan_Ponce_de_Leon_monument.jpg) Statue of Ponce de León

Statue of Ponce de León

The former Hotel Alcazar now houses the Lightner Museum and City Hall

The former Hotel Alcazar now houses the Lightner Museum and City Hall Flagler College, formerly the Ponce de Leon Hotel

Flagler College, formerly the Ponce de Leon Hotel.jpg) Bridge of Lions, looking eastward to Anastasia Island

Bridge of Lions, looking eastward to Anastasia Island.jpg) Tolomato Cemetery

Tolomato Cemetery

See also

- Recent scholarship has revealed that the first recorded St. Patrick's Day celebration in what is now the United States was held at St. Augustine in March 1601; according to Michael Francis's 2017 research in the Spanish Archives of the Indies (Archivo General de Indias), the citizens of St. Augustine marched on that date in a procession to honor the feast day of St. Patrick (San Patricio), organized by the Spanish Colony's Irish vicar Ricardo Artur (Richard Arthur).[78]

- Gálveztown (brig sloop) – ship which played a role in the Gulf Coast campaign of the American Revolutionary War under Bernardo de Gálvez, and its replica built recently in Spain anticipating the 450th anniversary of St. Augustine's founding (1565–2015).

- St. Augustine movement

References

- 1 2 "GNIS Detail – Saint Augustine". Geographic Names Information System. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2017-08-24. Retrieved Jul 7, 2017.

- 1 2 "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "State & County QuickFacts". Census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. April 1, 2016. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Archived from the original on 2017-05-29. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Florida: St. Augustine Town Plan Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2015-04-30. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "2012 Urbanized Area Population Estimates" (PDF). DOT.State.Fl.US. Florida Department of Transportation. April 1, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

- ↑ Hennesey, James J. (10 December 1981). American Catholics: A History of the Roman Catholic Community in the United States: A History of the Roman Catholic Community in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-802036-3.

- ↑ John T. McGrath (2000). The French in Early Florida: In the Eye of the Hurricane. University Press of Florida. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8130-1784-6.

- ↑ Eugene Lyon (May 1983). The Enterprise of Florida: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and the Spanish Conquest of 1565-1568. University Press of Florida. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-8130-0777-9.

- ↑ Eugene Lyon (May 1983). The Enterprise of Florida: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and the Spanish Conquest of 1565-1568. University Press of Florida. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-8130-0777-9.

- ↑ Pickett, Margaret F.; Pickett, Dwayne W. (8 February 2011). The European Struggle to Settle North America: Colonizing Attempts by England, France and Spain, 1521–1608. McFarland. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7864-6221-6.

...Laudonnière decided to call it the River of Dolphins (today known as the Matanzas River, near St. Augustine).

- ↑ John W. Griffin; Patricia C. Griffin (1996). Fifty Years of Southeastern Archaeology: Selected Works of John W. Griffin. University Press of Florida. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8130-1420-3.

- ↑ John William Reps (1965). The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States. Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-691-00618-0.

- ↑ Charlton W. Tebeau (1 January 1971). A History of Florida. University of Miami Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-87024-149-9.

- ↑ David J. Weber (1992). The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-300-05917-5.

- ↑ Albert C. Manucy (1983). Menéndez: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Captain General of the Ocean Sea. Pineapple Press. p. 95.

- ↑ Spencer Tucker (21 November 2012). Almanac of American Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3.

- ↑ John Sugden (24 April 2012). Sir Francis Drake. Random House. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-4481-2950-8.

- ↑ Angus Konstam (20 December 2011). The Great Expedition: Sir Francis Drake on the Spanish Main 1585–86. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-78096-233-7.

- ↑ James W. Raab (5 November 2007). Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida, 1763-1783. McFarland. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7864-3213-4.

- ↑ Alan Gallay (11 June 2015). Colonial Wars of North America, 1512-1763 (Routledge Revivals): An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-317-48718-0.

- ↑ "Charter of Carolina - March 24, 1663". Avalon Law. Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. 2008. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ Walter B. Edgar (1998). South Carolina: A History. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4.

- ↑ Jon Latimer (1 June 2009). Buccaneers of the Caribbean: How Piracy Forged an Empire. Harvard University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-674-03403-7.

- ↑ James W. Raab (5 November 2007). Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida, 1763-1783. McFarland. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-7864-3213-4.

- ↑ Marley, David (2010). Pirates of the Americas. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842012. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ↑ Walter B. Edgar (1998). South Carolina: A History. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4.

- ↑ Rodney E. Baine (2000). "General James Oglethorpe and the Expedition Against St. Augustine". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Georgia Historical Society. 84 (2 Summer): 198. JSTOR 40584271.

- ↑ Patricia C. Griffin (1991). Mullet on the Beach: The Minorcans of Florida, 1768-1788. St. Augustine Historical Society. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8130-1074-8.

- ↑ Jane G. Landers (2000). Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida. University Press of Florida. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-8130-1772-3.

- ↑ Patricia C. Griffin (1991). Mullet on the Beach: The Menorcans of Florida, 1768-1788. St. Augustine Historical Society. pp. 14–21. ISBN 978-0-8130-1074-8.

- ↑ Writers' Program (Fla.) (1940). Seeing Fernandina: A Guide to the City and Its Industries. Fernandina News Publishing Company. p. 23. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ James A. Crutchfield; Candy Moutlon; Terry Del Bene (26 March 2015). The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-45461-8.

- ↑ Stephen W. Stathis (2 January 2014). Landmark Legislation 1774-2012: Major U.S. Acts and Treaties. SAGE Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4522-9229-8.

- ↑ Barbara E. Mattick (2003). "The Catholic Nuns of St. Augustine (1859–1869)". In Bruce Clayton, John A. Salmond. Lives Full of Struggle and Triumph: Southern Women, Their Institutions, and Their Communities. University Press of Florida. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8130-3117-0.

- ↑ Paul Taylor (2001). Discovering the Civil War in Florida: A Reader and Guide. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-56164-235-9.

- ↑ Sidney Walter Martin (1 February 2010). Florida's Flagler. University of Georgia Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8203-3488-2.

- ↑ Jim Cox (24 February 2016). Rails Across Dixie: A History of Passenger Trains in the American South. McFarland. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7864-6175-2.

- ↑ Walter W. Manley; E. Canter Brown; Eric W. Rise; Florida Supreme Court Historical Society (1997). The Supreme Court of Florida and Its Predecessor Courts, 1821-1917. University Press of Florida. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8130-1540-8.

- ↑ Sidney Walter Martin (1 February 2010). Florida's Flagler. University of Georgia Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0-8203-3488-2.

- ↑ Tourism USA: Guidelines for Tourism Development : Appraising Tourism Potential, Planning for Tourism, Assessing Product and Market, Marketing Tourism, Visitor Services, Sources of Assistance. The University of Missouri. 1991. p. 87.

- ↑ Charles S. Bullock III; Mark J. Rozell (15 March 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Southern Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-19-538194-8.

- ↑ The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc. (1963). The Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc. p. 412. ISSN 0011-1422.

- ↑ Ron Ramdin (2004). Martin Luther King, Jr. Haus Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-904341-82-6.

- ↑ Thomas F. Jackson (17 July 2013). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-8122-0000-4.

- ↑ "FBI Report of 1964-02-08". OCLC. Federal Bureau of Investigation. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008.

(redacted) St. Augustine, Florida, advised that what appeared to be a Molotov cocktail was thrown at the back of his house at the above address causing a serious fire.

- ↑ John Kirk (6 June 2014). Martin Luther King Jr. Routledge. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-317-87650-2.

- ↑ Clive Webb (15 August 2011). Rabble Rousers: The American Far Right in the Civil Rights Era. University of Georgia Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8203-4229-0.

- ↑ Dorothy M. Singleton (18 March 2014). Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement and Thereafter: Profiles of Lessons Learned. UPA. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7618-6319-9.

- ↑ Larry Goodwyn (January 1965). "Anarchy in St. Augustine". Harpers.org. Harper’s Magazine. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015.

Sheriff Davis was beginning to use harsh treatment against demonstrators who were in jail. He would herd both men and women into a barbed-wire pen in the yard in a 99-degree sun; he kept them there all day. Water was insufficient and there was no latrine. At night the prisoners were crowded in small cells without room to lie down.

- ↑ Albert Vorspan; David Saperstein (1998). Jewish Dimensions of Social Justice: Tough Moral Choices of Our Time. UAHC Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-8074-0650-2.

- ↑ Stephen Haynes (8 November 2012). The Last Segregated Hour: The Memphis Kneel-Ins and the Campaign for Southern Church Desegregation. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-539505-1.

- ↑ Taylor Branch (16 April 2007). Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–65. Simon and Schuster. p. 606. ISBN 978-1-4165-5870-5.

- ↑ Nancy C. Curtis (1 August 1998). Black Heritage Sites: The South. The New Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-56584-433-9.

- ↑ Merline Pitre; Bruce A. Glasrud (20 March 2013). Southern Black Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement. Texas A&M University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-60344-999-1.

- ↑ David Goldfield (7 December 2006). Encyclopedia of American Urban History. SAGE Publications. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4522-6553-7.

- ↑ History News. 20-21. American Association for State and Local History. 1965. p. 208.

- ↑ Gardner, Sheldon (July 16, 2015). "King and queen of Spain to visit St. Augustine in September". The St. Augustine Record. Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ Martin, Jake (8 October 2016). "Hurricane Matthew: Surveying damage in St. Augustine the morning after". The St. Augustine Record. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ Braun, Michael (8 October 2016). "Hurricane Matthew floods St. Augustine beach areas". (Fort Myers) News-Press. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ "National Weather Service Climate". Nws.noaa.gov. 2006-07-21. Archived from the original on 2013-01-17. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-05-12. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "SGJ – Northeast Florida Regional Airport – SkyVector". skyvector.com. Archived from the original on 2015-05-14. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ "Elite Airways Announces New Service in Rochester MN, St. Augustine FL, Phoenix AZ, and Laughlin NV". WISTV. WISTV. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ↑ "Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind". Archived from the original on 2007-04-03. Retrieved 2007-03-27.

- ↑ "School is Tradition". The Florida Times-Union/Shorelines. February 13, 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ↑ Reiss, Sarah W. (2009). Insiders' Guide to Jacksonville, 3rd Edition. Globe Pequot. p. 184. ISBN 0-7627-5032-4. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ Reiss, Sarah W. (2009). Insiders' Guide to Jacksonville, 3rd Edition. Globe Pequot. pp. 184–187. ISBN 0-7627-5032-4. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ↑ Margaretta Jolly (4 December 2013). Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Routledge. p. 450. ISBN 978-1-136-78744-7.

- ↑ Robert Wayne Croft (1 January 2002). A Zora Neale Hurston Companion. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-313-30707-2.

- ↑ Harold Bloom (1 January 2009). Zora Neale Hurston. Infobase Publishing. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-4381-1553-5.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-02-06. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ↑ Seraphin, Charlie (5 December 2014). "People: Hurley Haywood". Old City Life. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ↑ James D. Kornwolf (2002). Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8018-5986-1.

- ↑ Michael Francis (December 21, 2017). "Blog of the Dead: Uncovering the Secrets of Spanish Florida". www.pbs.org. THIRTEEN Productions LLC. Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

Further reading

| Library resources about St. Augustine, Florida |

- Abbad y Lasierra, Iñigo, "Relación del descubrimiento, conquista y población de las provincias y costas de la Florida" – "Relación de La Florida" (1785); edición de Juan José Nieto Callén y José María Sánchez Molledo.

- Colburn, David, Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877–1980 (1985), New York: Columbia University Press.

- Corbett, Theodore G. "Migration to a Spanish imperial frontier in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: St. Augustine." Hispanic American Historical Review (1974): 414-430 in JSTOR

- Deagan, Kathleen, Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom (1995), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Fairbanks, George R. (George Rainsford), History and antiquities of St. Augustine, Florida (1881), Jacksonville, Florida, H. Drew.

- Gannon, Michael V., The Cross in the Sand: The Early Catholic Church in Florida 1513–1870 (1965), Gainesville: University Presses of Florida.

- Goldstein, Holly Markovitz, "St. Augustine's "Slave Market": A Visual History," Southern Spaces, 28 September 2012.

- Gordon, Elsbeth, Florida's Colonial Architectural Heritage, University Press of Florida, 2002; Heart and Soul of Florida: Sacred Sites and Historic Architecture, University Press of Florida, 2013

- Graham, Thomas, The Awakening of St. Augustine, (1978), St. Augustine Historical Society

- Hanna, A. J., A Prince in Their Midst, (1946), Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Harvey, Karen, America's First City, (1992), Lake Buena Vista, Florida: Tailored Tours Publications.

- Harvey, Karen, St. Augustine Enters the Twenty-first Century, (2010), Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Company.

- Landers, Jane, Black Society in Spanish Florida (1999), Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Lardner, Ring, Gullible's Travels, (1925), New York: Scribner's.

- Lyon, Eugene, The Enterprise of Florida, (1976), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Manucy, Albert, Menendez, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

- Marley, David F. (2005), "United States: St. Augustine", Historic Cities of the Americas, 2, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, p. 627+, ISBN 1-57607-027-1

- McCarthy, Kevin (editor), The Book Lover's Guide to Florida, (1992), Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press.

- Nolan, David, Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida, (1984), New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Nolan, David, The Houses of St. Augustine, (1995), Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press.

- Porter, Kenneth W., The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People, (1996), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Reynolds, Charles B. (Charles Bingham), Old Saint Augustine, a story of three centuries, (1893), St. Augustine, Florida E. H. Reynolds.

- Torchia, Robert W., Lost Colony: The Artists of St. Augustine, 1930–1950, (2001), St. Augustine: The Lightner Museum.

- Turner, Glennette Tilley, Fort Mose, (2010), New York: Abrams Books.

- United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965. Law Enforcement: A Report on Equal Protection in the South. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Warren, Dan R., If It Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States' Rights in St. Augustine, 1964, (2008), Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Waterbury, Jean Parker (editor), The Oldest City, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

Images

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. Augustine, Florida. |

- Freedom Trail, information about the civil rights movement in St. Augustine and the Freedom Trail that marks its sites.

- St. Augustine Pics, Daily pictures of St. Augustine, Florida.

- Twine Collection, more than 100 images of people in the St. Augustine African-American neighborhood of Lincolnville between 1922 and 1927. From the State Library & Archives of Florida.

- Unearthing St. Augustine's Colonial Heritage, App featuring more than 25,000 images of maps, drawings, photographs and documents related to Spanish colonial St. Augustine (with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities). From the University of Florida, the St. Augustine City Archaeology Program, the St. Augustine Historical Society, the Government House Research Library, and UF Historic St. Augustine, Inc.

External links

Government resources

Local news media

- The St. Augustine Record/staugustine.com, the city's daily print and online newspaper

- Historic City News, daily online news journal

Historical

- Castillo de San Marcos official website, U.S. National Park Service

- St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum

- Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP), maritime archaeology in St. Augustine

- History page (augustine.com)

- "St. Augustine Movement" in online King Encyclopedia (Stanford University)

- "St. Augustine Movement 1963–1964", Civil Rights Movement Veterans website

Higher education