Rococo

Rococo (/rəˈkoʊkoʊ/ or /roʊkəˈkoʊ/), less commonly roccoco, or "Late Baroque", was an exuberantly decorative 18th-century European style of art, architecture and interior decoration generally holding sway between about 1730 and 1780. In many respects, it is considered the final expression of the Baroque movement which had dominated the 17th century.[1] The Rococo style pushed to the extreme the principles of illusion and theatricality, an effect achieved by dense ornament, asymmetry, fluid curves, and the use of white and pastel colours combined with gilding, drawing the eye in all directions. The ornament dominated the architectural space.[1]

The Rococo style of architecture and decoration began in France in the first part of the 18th century in the reign of Louis XV as a reaction against the more formal and geometric Style Louis XIV. It was known as the style rocaille, or rocaille style [2] and quickly spread to other parts of Europe, particularly Bavaria, Austria, other parts of Germany, and Russia. It also came to influence the other arts, particularly painting, sculpture, literature, music, and theatre.[3] Rococo artists and architects used a more jocular, florid, and graceful approach to the Baroque including playful and witty themes. The interior decoration of Rococo rooms was designed as a total work of art with elegant and ornate furniture, small sculptures, ornamental mirrors, and tapestry complementing architecture, reliefs, and wall paintings. Rococo was also influenced by chinoiserie and sometimes it incorporated Chinese figures and pagodas.

In many parts of Europe, the Rococo influence on architecture is hard to discern as Baroque architecture already featured very elaborate exterior ornamentation. As a result, many buildings built in the mid-18th century are referred to as representing both styles, but there are cases where a simpler albeit more playful design was used that is called exclusively Rococo as opposed to Baroque. In painting, the difference between Baroque and Rococo is more noticeable and Rococo painting largely replaced Baroque painting in the first thirty years of the 18th century. As a result, many buildings across Europe are said to have Baroque architecture with Rococo interior decoration, including rococo frescos on their walls and ceilings.

Origin of the term

The word rococo was first used in 1835 in France, as a humorous variation of the word rocaille or a combination of rocaille and baroque.[4][5] Rocaille was originally a method of decoration, using pebbles, seashells and cement, which was often used to decorate grottoes and fountains since the Renaissance.[6][7] In the late 17th and early 18th century it became the term for a kind of decorative motif or ornament that appeared in the late Style Louis XIV, in the form of a seashell interlaced with acanthus leaves. In 1736 the designer and jeweler Jean Mondon published the Premier Livre de forme rocquaille et cartel, a collection of designs for ornaments of furniture and interior decoration. It was the first appearance in print of the term "rocaille" to designate the style.[8] The carved or molded seashell motif was combined with palm leaves or twisting vines to decorate doorways, furniture, wall panels and other architectural elements.[9]

In the 19th century, the term was used to describe architecture or music which was excessively ornamental.[10][11] Since the mid-19th century, the term has been accepted by art historians. While there is still some debate about the historical significance of the style, Rococo is now widely recognized as a major period in the development of European art.

Characteristics

Lavishly decorated architecture had appeared earlier in the Baroque period in the architecture of Francesco Borromini in Rome, Guarino Guarini in northern Italy, and in the extremely decorative churches of the Churrigueresque architects in Grenada and Seville in Spain; but many Rococo architects took a different approach. The exteriors of Rococo buildings are often simple, while the interiors are entirely dominated by their ornament. The style was highly theatrical, designed to impress and awe at first sight. Floor plans of churches were often complex, featuring interlocking ovals; In palaces, grand stairways became centrepieces, and offered different points of view of the decoration.[12]

French Rococo

The Rocaille style, or French Rococo, appeared in Paris during the reign Louis XV, and flourished between about 1723 and 1759.[13] The style was used particularly in salons, a new style of room designed to impress and entertain guests. The most prominent example was the salon of the Princess in Hôtel de Soubise in Paris, designed by Germain Boffrand and Charles-Joseph Natoire (1735–40). The characteristics of French Rococo included exceptional artistry, especially in the complex frames made for mirrors and paintings, which sculpted in plaster and often gilded; and the use of vegetal forms (vines, leaves, flowers) intertwined in complex designs.[14] The furniture also featured sinuous curves and vegetal designs. The leading furniture designers and craftsmen in the style included Juste-Aurele Meissonier, Charles Cressent, and Nicolas Pineau.[15][16]

The Rocaille style lasted in France until the mid-18th century, and while it became more curving and vegetal, it never achieved the extravagant exuberance of the Rococo in Bavaria, Austria and Italy. The discoveries of Roman antiquities beginning in 1738 at Herculanum and especially at Pompeii in 1748 turned French architecture in the direction of the more symmetrical and less flamboyant neo-classicism.

Salon of the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris (1735–40)

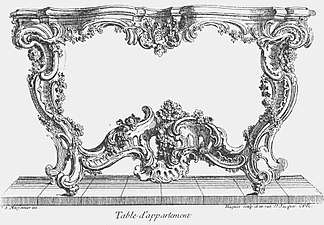

Salon of the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris (1735–40) Table design by Juste-Aurele Meissonier (1730)

Table design by Juste-Aurele Meissonier (1730)- Grand Chamber of the Prince, Hotel de Soubise (1735–40)

Woodwork in the Hôtel de Varengeville by Nicolas Pineau (1735)

Woodwork in the Hôtel de Varengeville by Nicolas Pineau (1735) Commode by Charles Cressent (1730), Waddleston Manor

Commode by Charles Cressent (1730), Waddleston Manor

Italy

Artists in Italy, particularly Venice, also produced an exuberant rococo style. Venetian commodes imitated the curving lines and carved ornament of the French rocaille, but with a particular Venetian variation; the pieces were painted, often with landscapes or flowers or scenes from Guardi or other painters, or Chinoiserie, against a blue or green background, matching the colours of the Venetian school of painters whose work decorated the salons. Notable decorative painters included Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who painted ceilings and murals of both churches and palazzos, and Giovanni Battista Crosato who painted the ballroom ceiling of the Ca Rezzonico in the quadraturo manner, giving the illusion of three dimensions. Tiepelo travelled to Germany with his son in 1752-54, decorating the ceilings of the Würzburg Residence, one of the major landmarks of the Bavarian rococo. An earlier celebrated Venetian painter was Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, who painted several notable church ceilings. [17]

The Venetian Rococo also featured exceptional glassware, particularly Murano glass, often engraved and coloured, which was exported across Europe. Works included multicolour chandeliers and mirrors with extremely ornate frames. [17]

_-_The_Glory_of_St._Dominic_by_Piazzetta.jpg) Ceiling of church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, by Piazzetta (1727)

Ceiling of church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, by Piazzetta (1727) Juno and Luna by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1735–45)

Juno and Luna by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1735–45) Murano glass chandelier at the Ca Rezzonico (1758)

Murano glass chandelier at the Ca Rezzonico (1758)_-_Ceiling_of_the_Ballroom.jpeg) Ballroom ceiling of the Ca Rezzonico with ceiling by Giovanni Battista Crosato (1753)

Ballroom ceiling of the Ca Rezzonico with ceiling by Giovanni Battista Crosato (1753)

Southern Germany and Austria

Between 1680 and 1750 a large number of important palaces and chateaux were constructed in Germany and Austria, as well as abbeys, built by religious orders, which were intended as pilgrimage destinations and were sumptuously decorated.[18] These became the grand showcases of the Baroque movement. They were frequently built by Italian craftsmen, or those who had been trained in Italy. One of the early creators of the rococo style was Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, whose major works included the Schoenbrun Palace, and Karlskirche in Vienna (1716-1729) which combined the grandeur and art of Versailles with that of the Italian Baroque. The Karlskirche featured an oval dome, lavishly painted, over the nave. Like many later rococo churches, it combined rococo in a framework of classical columns and pediments. [19]

While Vienna and Prague were major centres of late Baroque and Rococo, impressive palaces and churches were constructed in the regions of Swabia, Bavaria, Franconia; Dresden and Potsdam also became centres of Rococo.[20] Balthasar Neumann (1687–1753) took the rococo to a new level of lavishness Neumann was the author of the Würzburg Residence (1737) which Neumann called "a theater of light". A stairway with three ramps wound upwards toward a ceiling painted by Tiepolo.[21] A stairway was also the central element in a residence he built at the Augustusburg Palace in Brühl (1743–1748). There the stairway was the central feature, taking visitors up through a stucco fantasy of paintings, sculpture, ironwork and decoration, with surprising views at every turn.(1741–1744),[22]

Interior of the elliptical dome of the Karlskirche in Vienna, by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach (1716–29)

Interior of the elliptical dome of the Karlskirche in Vienna, by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach (1716–29)- Interior of the Basilica of the Fourteen Holy Helpers by Balthasar Neumann (1743–1772)

The Kaisersaal in the Würzburg Residence by Balthasar Neumann (1737)

The Kaisersaal in the Würzburg Residence by Balthasar Neumann (1737) Looking up the central stairway at Augustusburg Palace in Brühl by Balthasar Neumann (1741–44)

Looking up the central stairway at Augustusburg Palace in Brühl by Balthasar Neumann (1741–44)

Other important figures in the German rococo or late baroque include Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann and Balthasar Permoser, who designed the Zwinger Pavilion in Dresden (1709–1728) a space designed for ceremonies and celebration, is highly theatrical, with an overflow of decoration on the facade and a grand stairway in the interior. The building was destroyed during the Second World War, but has been reconstructed.

Johann Michael Fischer was the architect of Ottobeuren Abbey (1748–1766), the most celebrated Bavarian rococo landmark. The church features, like much of the rococo architecture in Germany, a remarkable contrast between the regularity of the facade and the overabundance of decoration in the interior.[21]

Another major rococo landmark in Bavaria is the Hunting Pavilion of Amalienburg, in Munich, by François de Cuvilliés.

Britain

In Great Britain, rococo was called the "French taste" and had less influence on design and the decorative arts than in continental Europe. although its influence was felt in such areas as silverwork, porcelain, and silks. William Hogarth helped develop a theoretical foundation for Rococo beauty. Though not mentioning rococo by name, he argued in his Analysis of Beauty (1753) that the undulating lines and S-curves prominent in Rococo were the basis for grace and beauty in art or nature (unlike the straight line or the circle in Classicism).[23]

Rococo was slow in arriving in England. Before entering the Rococo, British furniture for a time followed the neoclassical Palladian model under designer William Kent, who designed for Lord Burlington and other important patrons of the arts. Kent travelled to Italy with Lord Burlington between 1712 and 1720, and brought back many models and ideas from Palladio. He designed the furniture for Hampton Court Palace (1732), Lord Burlington's Chiswick House (1729), London, Thomas Coke's Holkham Hall, Norfolk, Robert Walpole's pile at Houghton, for Devonshire House in London, and at Rousham. .[24]

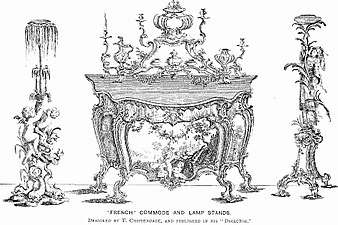

Mahogany made its appearance in England in about 1720, and immediately became popular for furniture, along with walnut wood. The Rococo began to make an appearance in England between 1740 and 1750. The furniture of Thomas Chippendale was the closest to the Rococo style, In 1754 he published "Gentleman's and Cabinet-makers' directory", a catalog of designs for rococo, chinoiserie and even Gothic furniture, which achieved wide popularity, going through three editions. Unlike French designers, Chippendale did not employ marquetry or inlays in his furniture. The predominant designer of inlaid furniture were Vile and Cob, the cabinet-makers for King George III. Another important figure in British furniture was Thomas Johnson, who in 1761, very late in the period, published a catalog of Roroco furniture designs. These include furnishings based on rather fantastic Chinese and Indian motifs, including a canopy bed crowned by a Chinese pagoda (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum).[17]

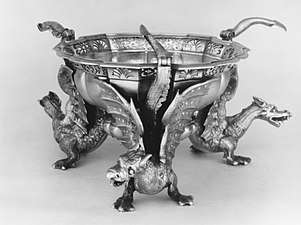

Other notable figures in the British Rococo included the silversmith Charles Friedrich Kandler.

Design for a State Bed by Thomas Chippendale (1753–54)

Design for a State Bed by Thomas Chippendale (1753–54) Proposed Chinese sofa by Thomas Chippendale (1753–54)

Proposed Chinese sofa by Thomas Chippendale (1753–54) Design for Commode and lamp stands by Thomas Chippendale (1753–54)

Design for Commode and lamp stands by Thomas Chippendale (1753–54) Side chair by Thomas Chippendale (1755–60)

Side chair by Thomas Chippendale (1755–60)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Design for candlesticks in the "Chinese Taste" by Thomas Johnson (1756)

Design for candlesticks in the "Chinese Taste" by Thomas Johnson (1756) Chippendale chair (1772), Metropolitan Museum

Chippendale chair (1772), Metropolitan Museum Brazier by silversmith Charles Friedrich Kander, (1735) Metropolitan Museum

Brazier by silversmith Charles Friedrich Kander, (1735) Metropolitan Museum

Decline and end

The art of Boucher and other painters of the period, with its emphasis on decorative mythology and gallantry, soon inspired a reaction, and a demand for more "noble" themes. While the rococo continued in Germany and Austria, the French Academy in Rome began to teach the classic style. This was confirmed by the nomination of Le Troy as director of the Academy in 1738, and then in 1751 by Charles-Joseph Natoire.

Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV contributed to the decline of the rococo style. In 1750 she sent her nephew, Abel-François Poisson de Vandières, on a two-year mission to study artistic and archeological developments in Italy. He was accompanied by several artists, including the engraver Nicolas Cochin and the architect Soufflot. They returned to Paris with a passion for classical art. Vandiéres became the Marquis of Marigny, and was named director general of the King's Buildings. He turned official French architecture toward the neoclassical. Cochin became an important art critic; he denounced the petit style of Boucher, and called for a grand style with a new emphasis on antiquity and nobility in the academies of painting and architecture.[25]

The beginning of the end for Rococo came in the early 1760s as figures like Voltaire and Jacques-François Blondel began to voice their criticism of the superficiality and degeneracy of the art. Blondel decried the "ridiculous jumble of shells, dragons, reeds, palm-trees and plants" in contemporary interiors.[26] By 1785, Rococo had passed out of fashion in France, replaced by the order and seriousness of Neoclassical artists like Jacques-Louis David. In Germany, late 18th-century Rococo was ridiculed as Zopf und Perücke ("pigtail and periwig"), and this phase is sometimes referred to as Zopfstil. Rococo remained popular in the provinces and in Italy, until the second phase of neoclassicism, "Empire style", arrived with Napoleonic governments and swept Rococo away.

Furniture and Decoration

The ornamental style called rocaille emerged in France between 1710 and 1750, mostly during the regency and reign of Louis XV; the style was also called Louis Quinze. Its principal characteristics were picturesque detail, curves and counter-curves, asymmetry, and a theatrical exuberance. On the walls of new Paris salons, the twisting and winding designs, usually made of gilded or painted stucco, wound around the doorways and mirrors like vines. One of the earliest examples was the Hôtel Soubise in Paris (1704–05), with its famous oval salon decorated with paintings by Boucher, and Charles-Joseph Natoire.[27]

The best known French furniture designer of the period was Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695–1750), who was also a sculptor, painter. and goldsmith for the royal household. He held the title of official designer to the Chamber and Cabinet of Louis XV. His work is well known today because of the enormous number of engravings made of his work which popularized the style throughout Europe. He designed works for the royal families of Poland and Portugal.

Italy was another place where the Rococo flourished, both in its early and later phases. Craftsmen in Rome, Milan and Venice all produced lavishly decorated furniture and decorative items.

- Candlelabra by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1735–40)

Chariot of Apollo design for a ceiling of Count Bielinski by Meissonier, Warsaw, Poland (1734)

Chariot of Apollo design for a ceiling of Count Bielinski by Meissonier, Warsaw, Poland (1734) Canapé designed by Meissonnier for Count Bielinski, Warsaw, Poland (1735)

Canapé designed by Meissonnier for Count Bielinski, Warsaw, Poland (1735)- Console table, Rome, Italy (circa 1710)

The sculpted decoration included fleurettes, palmettes, seashells, and foliage, carved in wood. The most extravagant rocaille forms were found in the consoles, tables designed to stand against walls. The Commodes, or chests, which had first appeared under Louis XIV, were richly decorated with rocaille ornament made of gilded bronze. They were made by master craftsmen including Jean-Pierre Latz and also featured marquetry of different-coloured woods, sometimes placed in checkerboard cubic patterns, made with light and dark woods. The period also saw the arrival of Chinoiserie, often in the form of lacquered and gilded commodes, called falcon de Chine of Vernis Martin, after the ebenist who introduced the technique to France. Ormolu, or gilded bronze, was used by master craftsmen including Jean-Pierre Latz. Latz made a particularly ornate clock mounted atop a cartonnier for Frederick the Great for his palace in Potsdam. Pieces of imported Chinese porcelain were often mounted in ormolu (gilded bronze) rococo settings for display on tables or consoles in salons. Other craftsmen imitated the Japanese art of lacquered furniture, and produced commodes with Japanese motifs. [28]

- Desk for the Münchner Residenz by Bernard II van Risamburgh (1737)

Clock-chest for Frederick the Great (1742)

Clock-chest for Frederick the Great (1742) A Chinese porcelain bowl and two fish mounted in gilded bronze, France (1745–49))

A Chinese porcelain bowl and two fish mounted in gilded bronze, France (1745–49)) An encoignure by royal cabinetmaker Jean-Pierre Latz (circa 1750)

An encoignure by royal cabinetmaker Jean-Pierre Latz (circa 1750) Lacquered Commode in Chinoiserie style, by Bernard II van Risamburgh, Victoria and Albert Museum (1750–1760)

Lacquered Commode in Chinoiserie style, by Bernard II van Risamburgh, Victoria and Albert Museum (1750–1760)

British Rococo tended to be more restrained. Thomas Chippendale's furniture designs kept the curves and feel, but stopped short of the French heights of whimsy. The most successful exponent of British Rococo was probably Thomas Johnson, a gifted carver and furniture designer working in London in the mid-18th century.

Interior design

.jpg)

Solitude Palace in Stuttgart, Chinese Palace in Oranienbaum, the Bavarian church of Wies, and Sanssouci in Potsdam are examples Rococo in European architecture. Sportive, fantastic, and sculptured forms are expressed with abstract ornament using flaming, leafy or shell-like textures in asymmetrical sweeps and flourishes and broken curves; intimate Rococo interiors suppress architectonic divisions of architrave, frieze, and cornice for the picturesque, the curious, and the whimsical, expressed in plastic materials like carved wood and above all stucco (as in the work of the Wessobrunner School). Walls, ceiling, furniture, and works of metal and porcelain present a unified ensemble. The Rococo palette is softer and paler than the rich primary colours and dark tonalities favored in Baroque tastes.

A few anti-architectural hints rapidly evolved into full-blown Rococo at the end of the 1720s and began to affect interiors and decorative arts throughout Europe. The richest forms of German Rococo are in Catholic Germany. Inaugurated in some rooms in Versailles, its magnificence unfolds in several Parisian buildings (especially the Hôtel Soubise). In Germany, Belgian and German artists (Cuvilliés, Neumann, Knobelsdorff, etc.) effected the dignified equipment of the Amalienburg near Munich, and the castles of Würzburg, Potsdam, Charlottenburg, Brühl, Bruchsal, Solitude (Stuttgart), and Schönbrunn.

In Great Britain, Hogarth's set of paintings forming a melodramatic morality tale titled Marriage à la Mode, engraved in 1745, shows the parade rooms of a stylish London house, in which the only rococo is in plasterwork of the salon's ceiling. Palladian architecture is in control. Here, on the Kentian mantel, the crowd of Chinese vases and mandarins are satirically rendered as hideous little monstrosities, and the Rococo wall clock is a jumble of leafy branches. Rococo plasterwork by immigrant Italian-Swiss artists like Bagutti and Artari is a feature of houses by James Gibbs, and the Lafranchini brothers working in Ireland equalled anything that was attempted in Great Britain.

Painting

Elements of the Rocaille style appeared in the work of some French artists, including a taste for the picturesque in details; curves and counter-curves; and dissymmetry which replaced the movement of the baroque with exuberance, though the French rocaille never reached the extravagance of the Germanic rococo.[29] The leading proponent was Antoine Watteau, particularly in Pilgrimage on the Isle of Cythera (1717), Louvre, in a genre called Fête Galante depicting scenes of young nobles gathered together to celebrate in a pastoral setting. Watteau died in 1721 at the age of thirty-seven, but his work continued to have influence through the rest of the century. The Pilgrimage to Cythera painting was purchased by Frederick the Great of Prussia in 1752 or 1765 to decorate his palace of Charlottenberg in Berlin.[29]

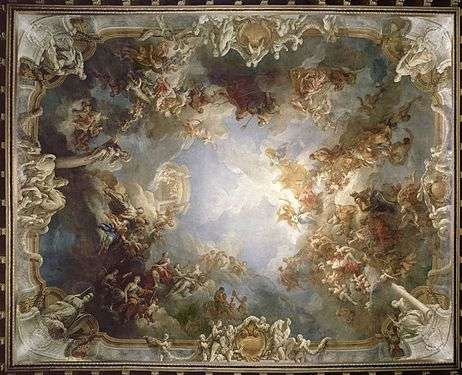

The successor of Watteau and the Féte Galante in decorative painting was François Boucher (1703–1770), the favorite painter of Madame de Pompadour. His work included the sensual Toilette de Venus (1746), which became one of the best known examples of the style. Boucher participated in all of the genres of the time, designing tapestries, models for porcelain sculpture, set decorations for the Paris opera and opera-comique, and decor for the Fair of Saint-Laurent. [30] Other important painters of the Fête Galante style included Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Baptiste Pater. The style particularly influenced François Lemoyne, who painted the lavish decoration of the ceiling of the Salon of Hercules at the Palace of Versailles, completed in 1735.[29] Paintings with fétes gallant and mythological themes by Boucher, Pierre-Charles Trémolières and Charles-Joseph Natoire decorated the famous salon of the Hôtel Soubise in Paris (1735–40).[30] Other Rococo painters include: Jean François de Troy (1679–1752), Jean-Baptiste van Loo (1685–1745), his two sons Louis-Michel van Loo (1707–1771) and Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo (1719–1795), his younger brother Charles-André van Loo (1705–1765), and Nicolas Lancret (1690–1743).

"Luncheon with Ham" by Nicolas Lancret (1735)

"Luncheon with Ham" by Nicolas Lancret (1735) Ceiling of the Salon of Hercules by François Lemoyne (1735)

Ceiling of the Salon of Hercules by François Lemoyne (1735) The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher (1746)

The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher (1746)

In Austria and Southern Germany, Italian painting had the largest effect on the Rococo style. The Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, assisted by his son, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, was invited to paint frescoes for the Würzburg Residence (1720–1744). The most prominent painter of Bavarian rococo churches was Johann Baptist Zimmermann, who painted the ceiling of the Wieskirche (1745–54)

Ceiling fresco in the Würzburg Residence (1720–1744) by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

Ceiling fresco in the Würzburg Residence (1720–1744) by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo Ceiling of the Wieskirche by Johann Baptist Zimmermann (1745–54)

Ceiling of the Wieskirche by Johann Baptist Zimmermann (1745–54)

Sculpture and Porcelain

.jpg)

Religious sculpture followed the Italian baroque style, as exemplified in the theatrical altarpiece of the Karlskirche in Vienna. However, much of Rococo sculpture was lighter and offered more movement than the classical style of Louis XIV. It was encouraged in particular by Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV, who commissioned many works for her chateaux and gardens. The sculptor Edmé Bouchardon represented Cupid engaged in carving his darts of love from the club of Hercules Rococo style—the demigod is transformed into the soft child, the bone-shattering club becomes the heart-scathing arrows, just as marble is so freely replaced by stucco. Étienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) was another leading French sculptor during the period. The French sculptors, Jean-Louis Lemoyne, Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, Louis-Simon Boizot, Michel Clodion, and Pigalle were also active. In Italy, Antonio Corradini was among the leading sculptors of the Rococo style. A Venetian, he travelled around Europe, working for Peter the Great in St. Petersburg, for the imperial courts in Austria and Naples. He preferred sentimental themes and made several skilled works of women with faces covered by veils, one of which is now in the Louvre.

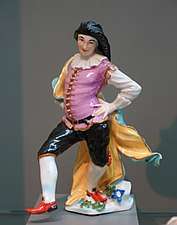

A new form of small-scale sculpture appeared, the porcelain figure, or small group of figures, initially replacing sugar sculptures on grand dining room tables, but soon popular for placing on mantelpieces and furniture. The number of European factories grew steadily through the century, and some made porcelain that the expanding middle classes could afford. The amount of colourful overglaze decoration used on them also increased. They were usually modelled by artists who had trained in sculpture. Common subjects included figures from the commedia dell'arte, city street vendors, lovers and figures in fashionable clothes, and pairs of birds.

Johann Joachim Kändler was the most important modeller of Meissen porcelain, the earliest European factory, which remained the most important until about 1760. The Swiss-born German sculptor Franz Anton Bustelli produced a wide variety of colourful figures for the Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory in Bavaria, which were sold throughout Europe. The French sculptor Étienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) followed this example. While also making large-scale works, he became director of the Sevres Porcelain manufactory and produced small-scale works, usually about love and gaiety, for production in series.

High altar of the Karlskirche in Vienna (1737)

High altar of the Karlskirche in Vienna (1737) Vertumnus and Pomone by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1760)

Vertumnus and Pomone by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1760)-black_bg.jpg) Pygmalion et Galatee by Étienne-Maurice Falconet (1763)

Pygmalion et Galatee by Étienne-Maurice Falconet (1763) The "Veiled Dame (Puritas) by Antonio Corradini (1722)

The "Veiled Dame (Puritas) by Antonio Corradini (1722)

.jpg)

Pair of lovers group of Nymphenburg porcelain, c. 1760, modelled by Franz Anton Bustelli

Pair of lovers group of Nymphenburg porcelain, c. 1760, modelled by Franz Anton Bustelli Figure of a cheese seller by Bustelli, Nymphenburg porcelain (1755)

Figure of a cheese seller by Bustelli, Nymphenburg porcelain (1755)

Music

A Rococo period existed in music history, although it is not as well known as the earlier Baroque and later Classical forms. The Rococo music style itself developed out of baroque music both in France, where the new style was referred to as style galante ("gallant" or "elegant" style), and in Germany, where it was referred to as empfindsamer Stil ("sensitive style"). It can be characterized as light, intimate music with extremely elaborate and refined forms of ornamentation. Exemplars include Jean Philippe Rameau, Louis-Claude Daquin and François Couperin in France; in Germany, the style's main proponents were C. P. E. Bach and Johann Christian Bach, two sons of the renowned J.S. Bach.

In the second half of the 18th century, a reaction against the Rococo style occurred, primarily against its perceived overuse of ornamentation and decoration. Led by C.P.E. Bach (an accomplished Rococo composer in his own right), Domenico Scarlatti, and Christoph Willibald Gluck, this reaction ushered in the Classical era. By the early 19th century, Catholic opinion had turned against the suitability of the style for ecclesiastical contexts because it was "in no way conducive to sentiments of devotion".[31]

Rococo Fashion

Rococo fashion was based on extravagance, elegance, refinement and decoration. Women’s fashion of the seventeenth-century was contrasted by the fashion of the eighteenth-century, which was ornate and sophisticated, the true style of Rococo.[32] These fashions spread beyond the royal court into the salons and cafés of the ascendant bourgeoisie.[33] The exuberant, playful, elegant style of decoration and design that we now know to be ‘Rococo’ was then known as ‘le style rocaille’, ‘le style moderne’, ‘le gout’.[34]

A style that appeared in the early eighteenth-century was the 'robe volante',[32] a flowing gown, that became popular towards the end of King Louis XIV’s reign. This gown had the features of a bodice with large pleats flowing down the back to the ground over a rounded petticoat. The colour palate was rich, dark fabrics accompanied by elaborate, heavy design features. After the death of Louis XIV the clothing styles began to change. The fashion took a turn to a lighter, more frivolous style, transitioning from the baroque period to the well-known style of Rococo.[35] The later period was known for their pastel colours, more revealing frocks, and the plethora of frills, ruffles, bows, and lace as trims. Shortly after the typical women’s Rococo gown was introduced, robe à la Françoise, [32] a gown with a tight bodice that had a low cut neckline, usually with a large ribbon bows down the centre front, wide panniers, and was lavishly trimmed in large amounts of lace, ribbon, and flowers.

The Watteau pleats [32] also became more popular, named after the painter Jean-Antoine Watteau, who painted the details of the gowns down to the stiches of lace and other trimmings with immense accuracy. Later, the 'pannier' and 'mantua' became fashionable around 1718, they were wide hoops under the dress to extend the hips out sideways and they soon became a staple in formal wear. This gave the Rococo period the iconic dress of wide hips combined with the large amount of decoration on the garments. Wide panniers were worn for special occasions, and could reach up to 16 feet (4.8 metres) in diameter,[36] and smaller hoops were worn for the everyday settings. These features originally came from seventeenth-century Spanish fashion, known as 'guardainfante', initially designed to hide the pregnant stomach, then reimagined later as the pannier.[36] 1745 became the Golden Age of the Rococo with the introduction of a more exotic, oriental culture in France called ‘a la turque’.[32] This was made popular by Louis XV’s mistress, Madame Pompadour, who commissioned the artist, Charles Andre Van Loo, to paint her as a Turkish sultana. In the 1760s, a style of less formal dresses emerged and one of these was the 'polonaise', with inspiration taken from Poland. It was shorter than the French dress, allowing the underskirt and ankles to be seen, which made it easier to move around in. Another dress that came into fashion was the ‘robe a l’anglais’, which included elements inspired by the males’ fashion; a short jacket, broad lapels and long sleeves.[35] It also had a snug bodice, a full skirt without panniers but still a little long in the back to form a small train, and often some type of lace kerchief worn around the neck. Another piece was the 'redingote', halfway between a cape and an overcoat.

Accessories were also important to all women during this time, as they added to the opulence and the decor of the body to match their gowns. At any official ceremony ladies were required to cover their hands and arms with gloves if their clothes were sleeveless.[35]

Gallery

Architecture

- Church of Saint Francis of Assisi (Ouro Preto) in São João del Rei, 1749–1774, by the Brazilian master Aleijadinho

Zwinger in Dresden

Zwinger in Dresden_2.jpg)

The Rococo Branicki Palace in Białystok, sometimes referred to as the "Polish Versailles"

The Rococo Branicki Palace in Białystok, sometimes referred to as the "Polish Versailles"- Electoral Palace of Trier

Basilica and Convent of Santo Domingo in Lima, Peru, completed in 1766

Basilica and Convent of Santo Domingo in Lima, Peru, completed in 1766

Engravings

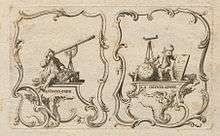

Unknown artist. Allegories of astronomy and geography. France (?), ca. 1750s

Unknown artist. Allegories of astronomy and geography. France (?), ca. 1750s A. Avelin after Mondon le Fils. L′Heureux moment. 1736

A. Avelin after Mondon le Fils. L′Heureux moment. 1736 A. Avelin after Mondon le Fils. Chinese God. An engraving from the ouvrage «Quatrieme livre des formes, orneė des rocailles, carteles, figures oyseaux et dragon» 1736

A. Avelin after Mondon le Fils. Chinese God. An engraving from the ouvrage «Quatrieme livre des formes, orneė des rocailles, carteles, figures oyseaux et dragon» 1736

Painting

Antoine Watteau, Pierrot, 1718–1719

Antoine Watteau, Pierrot, 1718–1719 Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to Cythera , 1718–1721

Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to Cythera , 1718–1721 Jean-Baptiste van Loo, The Triumph of Galatea, 1720

Jean-Baptiste van Loo, The Triumph of Galatea, 1720 Jean François de Troy, A Reading of Molière, 1728

Jean François de Troy, A Reading of Molière, 1728 Francis Hayman, Dancing Milkmaids, 1735

Francis Hayman, Dancing Milkmaids, 1735- Charles-André van Loo, Halt to the Hunt, 1737

Gustaf Lundberg, Portrait of François Boucher, 1741

Gustaf Lundberg, Portrait of François Boucher, 1741 François Boucher, Diana Leaving the Bath, 1742

François Boucher, Diana Leaving the Bath, 1742 Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, The Death of Hyacinth, 1752

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, The Death of Hyacinth, 1752.jpg)

Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Full-length portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1748–1755

Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Full-length portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1748–1755 François Boucher Portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1756

François Boucher Portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1756 Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767 Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Inspiration, 1769

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Inspiration, 1769

Jean-Honoré Fragonard The Meeting (Part of the Progress of Love series), 1771

Jean-Honoré Fragonard The Meeting (Part of the Progress of Love series), 1771 Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Marie Antoinette à la Rose, 1783

Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Marie Antoinette à la Rose, 1783

Rococo era painting

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Glass Flask and Fruit, c. 1750

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Glass Flask and Fruit, c. 1750

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Spoiled Child, c. 1765

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Spoiled Child, c. 1765 Joshua Reynolds, Robert Clive and his family with an Indian maid, 1765

Joshua Reynolds, Robert Clive and his family with an Indian maid, 1765 Angelica Kauffman, Portrait of David Garrick, c. 1765

Angelica Kauffman, Portrait of David Garrick, c. 1765 Louis-Michel van Loo, Portrait of Denis Diderot, 1767

Louis-Michel van Loo, Portrait of Denis Diderot, 1767

See also

- Rocaille

- Italian Rococo art

- Rococo in Portugal

- Rococo in Spain

- Cultural movement

- Gilded woodcarving

- History of painting

- Timeline of Italian artists to 1800

- Illusionistic ceiling painting

- Louis XV style

- Louis XV furniture

Notes and citations

- 1 2 Owens 2014, p. 92.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, p. 136.

- ↑ "Rococo style (design) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary On-Line

- ↑ Monique Wagner, From Gaul to De Gaulle: An Outline of French Civilization. Peter Lang, 2005, pp. 139. ISBN 0-8204-2277-0

- ↑ Larousse dictionary on-line

- ↑ Marilyn Stokstad, ed. Art History. 4th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2005. Print.

- ↑ De Morant, Henry, Histoire des arts décoratifs, p. 355

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier(2006) p. 66

- ↑ Ancien Regime Rococo. Bc.edu. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ↑ Rococo – Rococo Art. Huntfor.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-29.

- ↑ Hopkins 2014, p. 92.

- ↑ Lovreglio, Aurélia and Anne, Dictionnaire des Mobiliers et des Objets d'art, Le Robert, Paris, 2006, p. 369

- ↑ Hopkins, 2014 & pp. 92-93.

- ↑ De Morant 1970, p. 382.

- ↑ Kleiner, Fred (2010). Gardner's art through the ages: the western perspective. Cengage Learning. pp. 583–584. ISBN 978-0-495-57355-5. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 de Morant 1970, p. 383.

- ↑ Cabanne, 1988 & pp. 89-94.

- ↑ Cabanne 1988, pp. 89-91.

- ↑ Prina and Demartini (2006) pp. 220–223

- 1 2 Prina and Demartini (2006) pp. 222–223

- ↑ Prina and Demartini (2006) pp. 222-223

- ↑ "The Rococo Influence in British Art - dummies". dummies. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ↑ de Morant 1970, p. 382.

- ↑ Cabanne, 1988 & p. 106.

- ↑

- ↑ Cabanne 1988, p. 102.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 Cabanne 1988, p. 98.

- 1 2 Cabanne 1988, p. 104.

- ↑ Rococo Style – Catholic Encyclopedia. Newadvent.org (1912-02-01). Retrieved on 2014-02-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fukui, A., & Suoh, T. (2012). Fashion: A history from the 18th to the 20th century.

- ↑ "Posts about Baroque/Rococo 1650-1800 on History of Costume".

- ↑ Coffin, S. (2008). Rococo: The continuing curve, 1730-2008. New York.

- 1 2 3 "Marie Antoinette's Style Revolution". National Geographic. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- 1 2 Glasscock, J. "Eighteenth-Century Silhouette and Support". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

Bibliography

- De Morant, Henry (1970). Histoire des arts décoratifs. Librarie Hacahette.

- Droguet, Anne (2004). Les Styles Transition et Louis XVI. Les Editions de l'Amateur. ISBN 2-85917-406-0.

- Cabanne, Perre (1988), L'Art Classique et le Baroque, Paris: Larousse, ISBN 978-2-03-583324-2

- Ducher, Robert (1988), Caractéristique des Styles, Paris: Flammarion, ISBN 2-08-011539-1

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221--07862-4.

- Prina, Francesca; Demartini, Elena (2006). Petite encylopédie de l'architecture. Paris: Solar. ISBN 2-263-04096-X.

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Les styles en architecture. Dunod. ISBN 978-2-10-070689-1.

- Renault, Christophe (2006), Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, Paris: Gisserot, ISBN 978-2-877-4746-58

- Texier, Simon (2012), Paris- Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours, Paris: Parigramme, ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8

- Dictionnaire Historique de Paris. Le Livre de Poche. 2013. ISBN 978-2-253-13140-3.

- Vila, Marie Christine (2006). Paris Musique- Huit Siècles d'histoire. Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-419-3.

- Marilyn Stokstad, ed. Art History. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2005. Print.

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2014). The Spiritual Rococo: Décor and Divinity from the Salons of Paris to the Missions of Patagonia. Farnham: Ashgate.

Further reading

- Kimball, Fiske (1980). The Creation of the Rococo Decorative Syle. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23989-6.

- Arno Schönberger and Halldor Soehner, 1960. The Age of Rococo. Published in the US as The Rococo Age: Art and Civilization of the 18th Century (Originally published in German, 1959).

- Levey, Michael (1980). Painting in Eighteenth-Century Venice. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1331-1.

- Kelemen, Pál (1967). Baroque and Rococo in Latin America. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21698-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rococo architecture. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rococo art. |

| Look up rococo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- All-art.org: Rococo in the "History of Art"

- "Rococo Style Guide". British Galleries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- Bergerfoundation.ch: Rococo style examples

- Barock- und Rococo- Architektur, Volume 1, Part 1, 1892(in German) Kenneth Franzheim II Rare Books Room, William R. Jenkins Architecture and Art Library, University of Houston Digital Library.