COVIDSafe

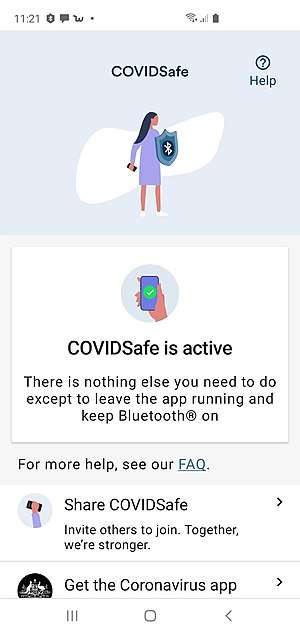

COVIDSafe[10][11] is a digital contact tracing app announced by the Australian Government on 14 April 2020 to help combat the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[12] The app is based on the BlueTrace protocol developed by the Singaporean Government,[13][14] and was first released on 26 April 2020.[15][16] The app augments traditional contact tracing by automatically tracking encounters between users, and later allowing a state or territory health authority to warn a user they have come within 1.5 metres with an infected patient for 15 minutes or more.[17] The functionality is not part of the previously published Coronavirus Australia app.[18][19][20]

| |

Screenshot  | |

| Developer(s) |

|

|---|---|

| Initial release | 26 April 2020 |

| Stable release | IOS 1.5 Build 31; Android 1.0.21

/ 5 June 2020 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | |

| Operating system | Android, iOS |

| Platform | Amazon Web Services[6] |

| Size |

|

| Standard(s) | |

| Available in | English |

| Type | Digital contact tracing |

| Licence | Proprietary, source code released[9] |

| Website | www |

History

COVIDSafe first began development shortly after the Morrison Government showed interest in Singapore's TraceTogether app in late March.[21] It was announced that an app was in development on 14 April 2020,[12] with plans to release it for Android and iOS within a fortnight.[22] The app had a budget of over A$2 million, A$700,000 of which went to AWS for hosting, development, and support.[23] The announcement was immediately met with concerns about the privacy of the app, and there was confusion over whether the app would be a feature of the existing Coronavirus Australia app or completely separate.[24][25] Adding to the confusion, many news reports used images of Coronavirus Australia,[26][27] and upon launch the COVIDSafe website temporarily linked to the Coronavirus Australia apps.[28]

The app launched on 26 April 2020. However, there were early reports that some users had problems with the sign-up. For example, those with non-Australian phone numbers did not receive a registration pin to the phone number they provided.

Within 24 hours of COVIDSafe's release more than a million people had downloaded it,[29] and within 48 hours more than two million.[30] By the second week more than four million users had registered.[31] Despite this state and territory health authorities were not yet able to access data collected through the app, although the Department of Health expected the app to be fully operational sometime during the first weeks of May.[32]

Accompanying the release, Peter Dutton, the Minister for Home Affairs, announced new legislation that would make it illegal to force anyone to hand over data from the app, even if they had registered and tested positive.[33][34] A determination, titled Biosecurity Determination 2020,[35] was put in place, with the Privacy Amendment (Public Health Contact Information) Bill 2020 being later introduced on 6 May 2020 to codify it.[36][37][38] The legislation governs how data collected by the app will be stored, submitted and processed.[35]

On 6 May 2020 the Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 held a public hearing on the COVIDSafe app, with particular focus towards its effectiveness and privacy implications.[39][1][2]

On 8 May 2020, the source code for the app was released publicly.[40][41]

On 13 May 2020, the Australian Chief Medical Officer announced that the app was fully functional.[42] The next day it was reported that the app had reached 5.7 million downloads, approximately 23% of Australia's total population.[43][44]

On 20 May 2020, the first patient data was accessed,[45][46] following an outbreak at Kyabram Health in Victoria.[47]

By mid June, over a month since the launch of the app, the app had yet to identify any contacts not already discovered through traditional contact tracing techniques,[48][49][50] further strengthening growing concerns over the effectiveness of the app.[51][52] Adding to this, some estimates put the likelihood of the app registering a random encounter at ~4%.[53][54][55] At the same time, the Google/Apple exposure notification framework began rolling out to users,[56] with the Italian Immuni being the first app to make use of it.[57][58]

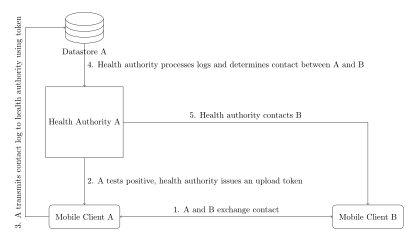

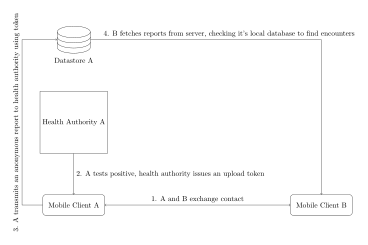

Contact tracing

The app is built on the BlueTrace protocol originally developed by the Singaporean Government.[59] A major focus of the design was the preservation of privacy for all users.[60][61] In order to achieve this personal information is collected only once at point of registration and used only to contact potentially infected patients.[62] Additionally, users are able to opt out at any time, clearing all personal information. Contact tracing is done entirely locally on a user's device using Bluetooth, storing all encounters in a contact history log chronicling contact for the past 21 days.[63] Users in contact logs are identified using anonymous time-shifting "temporary IDs" issued by the Department of Health (DoH). This means a user's identity cannot be ascertained by anyone except the DoH. Additionally, since temporary IDs change on a regular basis, malicious third parties cannot track users by observing log entries over time.[2]:02:51:10

Once a user tests positive for infection, the DoH requests the contact log. If the user chooses to share their log, it is sent to the health authority where they match the temporary ID with contact information. Health authorities are not able to access log entries about foreign users, so those entries are sent to the appropriate health authority to be processed there. Once a log has been processed, the DoH or appropriate health authority contacts the users contained within.[64]

Although commonly claimed that the app only logs encounters longer than 15 minutes and closer than 1.5 metres,[65][66] the app actually indiscriminately logs most encounters, and it is only once the health authority receives a contact log that it is filtered to encounters within 1.5 metres and longer than 15 minutes.[2]:02:51:15, 02:52:40[67]

Reporting centralisation

One of the largest privacy concerns raised about the BlueTrace protocol currently used by the app is the centralised report processing architecture.[68][69][70][71][72][73] In a centralised report processing protocol a user must upload their entire contact log to a health authority administered server, where the health authority is then responsible for matching the log entries to contact details, ascertaining potential contact, and ultimately warning users of potential contact.[64] Alternatively, the Exposure Notification framework and other decentralised reporting protocols, while still having a central reporting server, delegate the responsibility to process logs to clients on the network. Instead of a client uploading it's contact history, it uploads a number from which encounter tokens can be derived by individual devices.[74] Clients then check these tokens against their local contact logs to determine if they have come in contact with an infected patient.[75] Inherent in the fact the protocol never allows the government access to contact logs, this approach has major privacy benefits. However, this method also presents some issues, primarily the lack of human in the loop reporting, leading to a higher occurrence of false positives;[76][64] and potential scale issues, as some devices might become overwhelmed with a large number of reports. Decentralised reporting protocols are also less mature than their centralised counterparts.[59][77][78]

Protocol change

During the 6 May 2020 Senate Select Committee public hearing on COVID-19 and the COVIDSafe app,[39] it was revealed the DTA was looking into transitioning the protocol from BlueTrace to the Google and Apple developed Exposure Notification framework (ENF).[79] The change was proposed to resolve the outstanding issues related to performance of third-party protocols on iOS devices.[8][2][79][80] Unlike BlueTrace, the Exposure Notification frameworks runs at the operating system level with special privileges not available to any third-party frameworks.[81][82] The adoption of the framework is endorsed by multiple technology experts.[83][84][85]

Transitioning from BlueTrace to ENF presented several issues, most notably that, as the app cannot run both protocols simultaneously,[86] any protocol change would be a hard cut between versions. This would result in the app no longer functioning for any users who had not yet updated to the ENF version of the app. Additionally, the two protocols are almost completely incompatible,[87][88] meaning the vast majority - all but the UI - of the COVIDSafe app would have to be redeveloped. Similarly, because of the change from a centralised reporting mechanism to a decentralised one, very little of the existing server software would be usable.[89] The role of state and territory health authorities in the process would also change significantly, as they would no longer be responsible for determining and contacting encounters.[89] This change would involve retraining health officials and penning new agreements with states and territories.

Up until at least 18 June 2020, the DTA was experimenting with ENF,[90] however in an interview with The Project held on 28 June 2020, Deputy Chief Medical Officer Dr Nick Coatsworth stated COVIDSafe would "absolutely not" transition to ENF.[91] He reasoned the government would never transition to any contact tracing solution without human-in-the-loop reporting,[92][93] something that no decentralised protocol can support.

Issues

Issues on iOS

Versions 1.0 and 1.1 of COVIDSafe did not scan for other devices when the application was placed in the background on iOS, resulting in much fewer contacts being recorded than was possible. This was later corrected in version 1.2 with improved behaviour.[94] Additionally, until the 18 June 2020 update, a bug existed where locked iOS devices did not fetch new temporary IDs.[95] This meant that a device's temporary ID pool could easily be exhausted unless the phone was unlocked when the app tried to refresh the pool.

However, all digital contact tracing protocols, with exception to the first party developed Google/Apple protocol, experience degraded performance on iOS devices.[96][64] These issues occur when the device is locked or the app is not in the foreground.[97][98] This is a limitation of the operating system, stemming from how iOS manages its battery life and resource priority.[99]:01:19:30 The Android app does not experience these issues because it can request the operating system to disable battery optimisation, and because Android is more permissive with background services.[100][99]:01:22:00

Country calling code restrictions

COVIDSafe requires an Australia mobile number to register, meaning foreigners in Australia need a local sim card.[101] Initially, residents of Norfolk Island, an external territory of Australia, were unable to register with the app as they used a different country code to mainland Australia, +672 instead of +61.[102][103][104] The Australian government released an update resolving the issue on 18 June 2020.[95][105]

Privacy concerns

Upon announcement, the app was immediately met with wide criticism over the potential privacy implications of tracking users.[106][107] While some criticism can be attributed to poor communication,[108][109] fears were further stoked when Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Deputy Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly refused to rule out the possibility of making the app compulsory, with Prime Minister Morrison stating the next day it would not be mandatory to download the app.[110][111][112] Additionally, several privacy watchdogs raised concerns over the data collected by the app, and the potential for the centralised reporting server to become a target for hackers.[113][114][115] In order to address concerns, the Attorney General launched an investigation into the app to ensure it had proper privacy controls and was sufficiently secure.[116] The Minister for Home Affairs, Peter Dutton, also announced special legislation to protect data collected through the app.[33] The app was supposed to be open sourced to allow it to be audited and analysed by the public,[117] however this was delayed[118] until a review by the Australian Signals Directorate had been completed.[119] On 8 May 2020 the source code was released.[40]

Issue was also taken with the fact the backend of the app runs on the Amazon Web Services (AWS) platform,[120] meaning the US Government could potentially seize the data of Australian citizens.[6] Data is currently stored within Australia[121] in the AWS Sydney region data centre.[122] In a public hearing on COVIDSafe, Randall Brugeaud, CEO of the Digital Transformation Agency, explained that the decision to use AWS over purely Australian owned cloud providers was done on the basis of familiarity, scalability, and resource availability within AWS.[2]:01:49:00 - 02:10:00; 02:52:01 - 03:05:00 The AWS contract was also drawn from a whole of government arrangement.[2]:02:59:30

Following the global rollout of the Google and Apple developed Exposure Notification Framework (ENF) in late June 2020,[123] public concerns were raised that the government or the companies were tracking users without their knowledge or consent.[124][125][126][127] These claims are false, as COVIDSafe and ENF are completely incompatible, and ENF is disabled until a compatible app is installed and explicit user consent is given.[128] Even if a third party were to obtain the encounter log of a user, no persons could be identified without also holding the logs of other users the client has encountered.[129]

Attorney General privacy impact assessment

On 25 April 2020 the Attorney General report and subsequent response by the Department of Health was released,[119] the following recommendations were made:

- Release the Privacy Impact Assessment and the app source code

- Major changes should be reviewed for privacy impact

- A legislative framework put in place to protect the user

- Certain screens be rearranged to better communicate information

- Make clear what a user should do if they are pressured to reveal their contact logs, or are pressured into installing the app

- Generalised collection of age

- Gather consent from users both at registration, and at submission of contact logs

- Create a specific privacy policy for the app

- Make it easier to rectify personal information

- Raise public awareness about the app and how it works

- Development of training and scripts for health officials

- Put in place contracts with state and territory health authorities

- Allow users to register under a pseudonym

- Seek independent review over security of the app

- Review the contract with AWS

- Ensure ICT contracts are properly documented

- Investigate ways to reduce the number of digital handshakes

- A special consent process for underage users

In the Department of Health's response, they agreed to all suggestions with exception to "rectification of personal information". Rather than building a process to do so, a user can simply uninstall and reinstall the app to change their personal information.[119]:p. 7 A process to formally correct information is to be introduced later.

Independent analysis

On 29 April 2020, a group of independent security researchers including Troy Hunt, Kate Carruthers, Matthew Robbins, and Geoffrey Huntley released an informal report raising a selection of issues discovered in the decompiled app.[130][99][131] Their primary concerns were two flaws in the implementation of the protocol that could potentially allow malicious third parties to ascertain static identifiers for individual clients.[132] Importantly, all issues raised in the report were related to incidental leaking of static identifiers during the encounter handshake.[130] To date, no code has been found that intentionally tracks the user beyond the scope of contact tracing, nor code that transmits a user's encounter history to third parties without the explicit consent of the user.[99][133][134] Additionally, despite the flaws discovered through their analysis, many prominent security researchers publicly endorse the app.[135][136][137][138]

The first issue was located in BLEAdvertiser.kt, the class responsible for advertising to other BlueTrace clients. The bug occurred with a supposedly random, regularly changing three-byte string included in that was, in fact, static for the entire lifetime of an app instance.[139][130]:Issue #2[140]:line 85-86 This string was included with all handshakes performed by the client. In OpenTrace this issue did not occur, as value changes every 180 seconds.[141] While likely not enough entropy to identify individual clients, especially in a densely populated area, when used in combination with other static identifiers (such as the phone's model) it could have been used by malicious actors to determine the identity of users.[130][131] This issue was addressed in the 13 May 2020 update.[142]

The second issue was located in GattServer.kt, the class responsible for managing BLE peripheral mode, where the cached read payload is incorrectly cleared. Although it functioned normally when a handshake succeeded, a remote client who broke the handshake would have received the same TempID for all future handshakes until one succeeded, regardless of time.[130]:Issue #1 This meant a malicious actor could always intentionally break the handshake and, for the lifetime of the app instance, the same TempID would always be returned to them. This issue was resolved in OpenTrace,[143] yet was unfixed in COVIDSafe[132][144] until the 13 May 2020 update.[142]

Other issues more inherent to the protocol include the transmission of device model as part of the encounter payload, and issues where static device identifiers could be returned when running in GATT mode.[130] Many of these are unfixable without redesigning the protocol, however they, like the other issues, pose no major privacy or security concerns to users.[131]

Legislation

The Biosecurity Determination 2020, made with the authority of the Biosecurity Act 2015,[145][146] governs how data collected by the COVIDSafe app is stored, submitted, and processed. Later a separate bill was introduced to codify this determination, the Privacy Amendment (Public Health Contact Information) Bill 2020.[37][38] The determination and bill makes it illegal for anyone to access COVIDSafe app data without both the consent of the device owner[35]:§7.1 and being an employee or contractor of a state or territory health authority.[35]:§6.2 Collected data may be used only for the purpose of contact tracing or anonymous statistical analysis,[35]:§6.2.a.ii & §6.2.e[147] and data also cannot be stored on servers residing outside Australia, nor can it be disclosed to persons outside Australia.[35]:§7.3[148] Additionally, all data must be destroyed once the pandemic has concluded, overriding any other legislation requiring data to be retained for a certain period of time.[35]:§7.5 The bill also ensures no entity may compel someone to install the app.[35]:§9[149] Despite this there have been reports of multiple businesses attempting to require employees to use the app.[150][151]

See also

References

- "THE SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON COVID-19 PUBLIC HEARING Committee Room 2S1 Parliament House, Canberra". Parliament of Australia. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "COVID-19 - 06/05/2020 12:50:00 – Parliament of Australia". parlview.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Atlassian and the CovidSafe team". InnovationAus. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Bitbucket". bitbucket.org. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "What you should know about CovidSafe app and the claim "Your identity is safeguarded."". moworks.com.au. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Besser, Linton; Welch, Dylan (24 April 2020). "Australians' data from COVID-19 tracing app to be held by US cloud giant Amazon". ABC News. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe: Australia's data-inspired path to containing the spread of COVID-19". Corrs Chambers Westgarth. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Australian government admits its COVIDSafe app doesn't work on iOS". iMore. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Taylor, Josh (29 April 2020). "Covidsafe app: how to download Australia's coronavirus contact tracing app and how it works". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- jasoncartwright (26 April 2020). "The Government's COVID-19 tracking app is called CovidSafe and is launching today!". techAU. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe - Apps on Google Play". play.google.com. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Editor, Political; Probyn, rew (14 April 2020). "The Government wants to track us via our phones. And if enough of us agree, coronavirus restrictions could ease". ABC News. Retrieved 17 April 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bogle, Ariel (17 April 2020). "Five questions we need answered about the government's coronavirus contact tracing app". ABC News. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Farr, Malcolm; Hurst, Daniel (14 April 2020). "Australian government plans to bring in mobile phone app to track people with coronavirus". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Privacy concerns as Australia's controversial coronavirus tracing app nears launch". SBS News. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "The coronavirus tracing app has been released. Here's what it looks like and what it wants to do". ABC News. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe: New app to slow the spread of coronavirus | Prime Minister of Australia". www.pm.gov.au. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Australia launches COVIDSafe contact tracing app". iTnews. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Controversial virus app now live". NewsComAu. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- xssfox (17 April 2020). "Tweet from xssfox". @xssfox. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Govt eyes Singapore COVID-19 tracking app". InnovationAus. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Government to release new contact tracing app within the next fortnight". www.msn.com. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Big bucks on open source COVIDsafe app". InnovationAus. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Brookes, Joseph (15 April 2020). "Contact Tracing: Australia's incoming technology solution for tracking COVID-19". Which-50. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus Australia - Apps on Google Play". play.google.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Government's COVID-19 tracing app to be launched today". 7NEWS.com.au. 25 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Remeikis, Amy (26 April 2020). "Australia's coronavirus tracing app set to launch today despite lingering privacy concerns". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe". 26 April 2020. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe app reaches five-day download goal within five hours". ABC News. 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "More than two million Australians download COVIDSafe contact tracing app". SBS News. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Bourke, Sarah Keoghan, Mary Ward, Latika (4 May 2020). "Coronavirus updates LIVE: Australians download COVIDSafe app more than 4.5 million times, global COVID-19 cases climb past 3.5 million as nation's death toll stands at 96". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus app tracing capability not yet operational, despite 4 million downloads - ABC News". www.abc.net.au. 2 May 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus app comes with privacy guarantee: Dutton". www.theaustralian.com.au. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus Australia live updates". news.com.au — Australia's #1 news site. 25 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Biosecurity (Human Biosecurity Emergency) (Human Coronavirus with Pandemic Potential) (Emergency Requirements—Public Health Contact Information) Determination 2020". Determination of 25 April 2020. Parliament of Australia.

- "Govt unveils COVIDSafe contact tracing app bill". iTnews. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Department, Attorney-General's. "COVIDSafe draft legislation". www.ag.gov.au. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Privacy Amendment (Public Health Contact Information) Bill 2020". Bill of 2020 (PDF). Parliament of Australia.

- corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra. "Public Hearings". www.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- AU-COVIDSafe, COVIDSafe, 8 May 2020, retrieved 8 May 2020

- Agency, Digital Transformation (8 May 2020). "DTA publicly releases COVIDSafe application source code". www.dta.gov.au. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus Australia live news: Paul Kelly says COVIID Safe app 'fully functional' with all states, territories signed up - ABC News". www.abc.net.au. 12 May 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Barbaschow, Asha. "Australian government justifies decision to go with AWS for COVIDSafe". ZDNet. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Taylor, Josh (19 May 2020). "NSW is unable to use Covidsafe app's data for contact tracing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "'One close contact' traced in first app test". www.weeklytimesnow.com.au. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Victorian health officials access coronavirus patient's COVIDSafe app data for first time | ABC News, retrieved 21 May 2020

- Coronavirus: COVIDSafe app tracks first infection in Victoria | Nine News Australia, retrieved 21 May 2020

- "COVIDSafe has not been much help at all, and authorities say that's a good thing". www.abc.net.au. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "No contacts through COVIDSafe app yet". InnovationAus. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Long, Trevor (25 June 2020). "CovidSafe app: 9News reports Not a single contact obtained via the app - is it working? » EFTM". EFTM. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Even 100% COVIDSafe Uptake Won't Make it Effective, Researcher Says". Gizmodo Australia. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "COVIDSafe 'extremely limited': New research". InnovationAus. 8 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Knox, James (29 May 2020). "COVIDSafe and safety first". Medical Forum. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Why should you install the COVIDSafe App? Part 2". Crush The Curve Today. 2 May 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- MP, Tim Watts (13 May 2020). "SPEECH: COVIDSafe Contact Tracing App". Medium. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "What it really means when "COVID-19 exposure notifications" is in your phone settings – Australian Associated Press". AustralianAssociatedPress. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Italy launches Immuni contact-tracing app: Here's what you need to know". www.thelocal.it. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Potuck, Michael (1 June 2020). "Italy launches one of the first Apple Exposure Notification API-based apps with 'Immuni'". 9to5Mac. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "TraceTogether - behind the scenes look at its development process". www.tech.gov.sg. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "COVID-19 contact tracing: Getting it done — and making it work - Loki Foundation". Loki Foundation. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "BlueTrace Manifesto". Team TraceTogether. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "PM: Change for schools, new app, exercise rules coming". www.dailytelegraph.com.au. 24 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Barbaschow, Asha. "Australia looks to 'go harder' with use of COVID-19 contact tracing app". ZDNet. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Jason Bay, Joel Kek, Alvin Tan, Chai Sheng Hau, Lai Yongquan, Janice Tan, Tang Anh Quy. "BlueTrace: A privacy-preserving protocol for community-driven contact tracing across borders" (PDF). Government Technology Agency. Retrieved 12 April 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "How COVIDsafe app tracks people 1.5m from you". Chronicle. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe Explained: Everything You Need To Know About the Australian Government's Coronavirus App". PC World. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Bitbucket". bitbucket.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Surman, Mark. "Privacy Norms and the Pandemic". The Mozilla Blog. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Das gefährliche Chaos um die Corona-App". www.tagesspiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "ZEIT ONLINE | Lesen Sie zeit.de mit Werbung oder imPUR-Abo. Sie haben die Wahl". www.zeit.de. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- SPIEGEL, DER. "Projekt Pepp-PT: Den Tracing-App-Entwicklern laufen die Partner weg - DER SPIEGEL - Netzwelt". www.spiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Zeitung, Süddeutsche. "Corona-App: Streit um Pepp-PT entbrannt". Süddeutsche.de (in German). Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- editor, Alex Hern Technology (20 April 2020). "Digital contact tracing will fail unless privacy is respected, experts warn". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 April 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "PEPP-PT vs DP-3T: The coronavirus contact tracing privacy debate kicks up another gear". NS Tech. 20 April 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "DP-3T whitepaper" (PDF). GitHub. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- hermesauto (15 June 2020). "Apple-Google contact tracing system not effective for Singapore: Vivian Balakrishnan". The Straits Times. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Initial commit · TCNCoalition/TCN@1b68b92". GitHub. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "DP-3T whitepaper" (PDF). GitHub. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Taylor, Josh (6 May 2020). "Covidsafe app is not working properly on iPhones, authorities admit". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Department for Health and Wellbeing (South Australia). "COVIDSafe app". www.sahealth.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Apple and Google update joint coronavirus tracing tech to improve user privacy and developer flexibility". TechCrunch. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Farr, Christina (28 April 2020). "How a handful of Apple and Google employees came together to help health officials trace coronavirus". CNBC. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Govt urged to ditch COVIDSafe for GApple". InnovationAus. 22 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Should Australia ditch the COVIDSafe app for the Apple and Google alternative?". SmartCompany. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Should Australia ditch the COVIDSafe app for the Apple and Google alternative?". The Mandarin. 28 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Exposure Notifications API | Google APIs for Exposure Notification". Google Developers. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Sheel, Meru; Lazar, Seth. "Contact tracing apps are vital tools in the fight against coronavirus. But who decides how they work?". The Conversation. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Jim Mussared, Eleanor McMurtry (24 May 2020). "The COVIDSafe App - 4 week update" (PDF). Melbourne School of Engineering - University of Melbourne. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Exposure Notifications: Helping fight COVID-19 - Google". Exposure Notifications: Helping fight COVID-19 - Google. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Australia's Covidsafe coronavirus tracing app works as few as one in four times for some devices". the Guardian. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "'No way' govt will switch to GApple app". InnovationAus. 29 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "The Project interview". Twitter. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Grubb, Ben (28 June 2020). "'There's no way we're shifting': Australia rules out Apple-Google coronavirus tracing method". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Nelson, Richard. "The Unbroken iOS COVIDSafe application".

- "Government releases sixth update for COVIDSafe app". www.technologydecisions.com.au. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "DTA admits COVIDSafe performance "highly variable" on iOS". iTnews. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Jones, Tegan (1 May 2020). "Why COVIDSafe Has Issues On iOS, As Explained By Devs". Gizmodo Australia. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Grubb, Ben (7 May 2020). "Half-baked: The COVIDSafe app is not fit for purpose on iPhones". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- COVIDSafe App Teardown & Panel Discussion, retrieved 7 May 2020

- Huntley, Geoffrey (7 May 2020), ghuntley/COVIDSafe_1.0.11.apk, retrieved 7 May 2020

- Elder, Glenn. "EMNI - MEDIA RELEASE" (PDF). Norfolk Island Regional Council. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Crellin, Zac (7 May 2020). "We Asked Every MP And Senator Whether They Downloaded COVIDSafe And Here's What They Said". Pedestrian.TV. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Dialing Code From Australia to Norfolk Island". www.dialingcode.com. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Agency, Digital Transformation. "Telephone country and area codes". telephone-country-and-area-codes. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Agency, Digital Transformation (19 June 2020). "More people in Australia can now download and use COVIDSafe". www.dta.gov.au. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Privacy recommendations for Australia's use of contact tracing mobile apps like TraceTogether". australiancybersecuritymagazine.com.au. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "COVID-19 contact tracing app: 'I get it, but I don't like it'". Australian Financial Review. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "What price privacy? Contact tracing apps to combat Covid". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "The GPS tracking app the government wants YOU to download so COVID lockdown can be lifted". 7NEWS.com.au. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Deputy CMO doesn't rule out forcing Australians to download contact tracing app". ABC News. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Morrison refuses to 'be drawn' on making contact tracing app compulsory". iTnews. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Scott Morrison says COVID-19 tracker app not mandatory". The New Daily. 18 April 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Meade, Amanda (18 April 2020). "Australian coronavirus contact tracing app voluntary and with 'no hidden agenda', minister says". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Jackson, Carl (6 April 2020). "TraceTogether, Singaporean COVID-19 contact tracing and Australian recommendations". Melbourne School of Engineering. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Greater transparency needed around Federal Government's new COVID 19 phone app". Human Rights Law Centre. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Taylor, Josh (18 April 2020). "Australia's coronavirus contact tracing app: what we know so far". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Scott Morrison Is Now Saying Australia's Coronvirus Tracing App Won't Be Mandatory". Gizmodo Australia. 18 April 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Health minister now unsure if source code for COVID contact tracing app is safe to release". iTnews. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Department of Health (25 April 2020). "COVIDSafe Privacy Impact Assessment – Agency Response" (PDF). Department of Health. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Government services minister insists COVID tracing app data safe on AWS". iTnews. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe Privacy Policy". health.gov.au. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Taylor, Josh (27 April 2020). "Covidsafe app: how to download Australia's coronavirus contact tracing app and how it works". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Apple and Google's Exposure Notification API has launched". clicklancashire.com. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Huynh, Terence (21 June 2020). "No, Apple and Google didn't secretly install a COVID-19 tracker on your phone". TechGeek. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Imgur. "COVIDSafe misinformation". Imgur. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Adjoa, Andoh (19 June 2020). "Viral twitter post about ENF update". Twitter. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Common ENF misinformation copypasta". Twitter. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Google's Coronavirus Contact Tracing Setting Isn't Tracking You". Gizmodo Australia. 22 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Apple, Inc (April 2020). "Exposure Notification - Cryptography Specification" (PDF). Apple. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "COVIDSafe Android App - BLE Privacy Issues". Google Docs. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Dissection of COVIDSafe (Android)". Google Docs. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- huntley, geoffrey (6 May 2020). "Issue 1 (which is a privacy breach) in @jim_mussared's research was confirmed by the Singapore team. It was fixed same day. It has not been fixed in the Australian app. Nb. I also disclosed see above tweets about being ignored.pic.twitter.com/wtGsy8Ki5R". @GeoffreyHuntley. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Robbins, Matthew (26 April 2020). "The #covidsafe app is now available in Australia. However, it's a shame that they have decided not to release the source code for full transparency. Luckily, I'm a curious chap and also a professional mobile developer". @matthewrdev. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Not sure whether to install the government's COVIDSafe app? Here's everything we know". The Feed. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Endorsing individuals". Endorse COVIDSafe. 1 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Experts Explain Why They're Not Worried About COVIDSafe". Gizmodo Australia. 30 April 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Wilson, Stephen (3 May 2020). "I'm a privacy expert - and I've downloaded COVIDSafe". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Stone, Gavin (15 May 2020). "Privacy expert backs government's 'good job' on COVIDSafe app". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- micolous. "AU generation algorithm is really subtlely different ..." Discord. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Bitbucket au/gov/health/covidsafe/bluetooth/BLEAdvertiser.java". bitbucket.org. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "opentrace-community/opentrace-android/blob/master/app/src/main/java/io/bluetrace/opentrace/bluetooth/BLEAdvertiser.kt". GitHub. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "COVIDSafe code from version 1.0.17 (#1) · AU-COVIDSafe/mobile-android@696e4ed". GitHub. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "fixed a bug where the cached read payload was not cleared properly · opentrace-community/opentrace-android@0c7f7f6". GitHub. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Bitbucket au/gov/health/covidsafe/bluetooth/gatt/GattServer.java". bitbucket.org. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "COVIDSafe legislation". Attorney General's Department. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Health. "Biosecurity (Human Biosecurity Emergency) (Human Coronavirus with Pandemic Potential) (Emergency Requirements—Public Health Contact Information) Determination 2020: Enabled by". www.legislation.gov.au. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "COVIDSafe App – Part Two: Legislation passed to address privacy concerns - What it means for you - Coronavirus (COVID-19) - Australia". www.mondaq.com. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "COVIDSafe privacy protections now locked in law". iTnews. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Barbaschow, Asha. "COVIDSafe legislation enters Parliament with a few added privacy safeguards". ZDNet. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Employers want power over COVIDSafe app". www.theaustralian.com.au. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Health Department investigating Strathfield Council for unlawfully forcing employees to download COVIDSafe". www.dailytelegraph.com.au. Retrieved 6 May 2020.