Toronto

| Toronto | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City (single-tier) | |||||

| City of Toronto | |||||

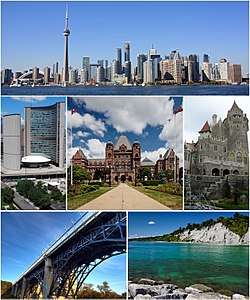

From top left: Downtown, City Hall, the Ontario Legislative Building, Casa Loma, Prince Edward Viaduct, and the Scarborough Bluffs | |||||

| |||||

| Etymology: From "Taronto", the name of a channel between Lakes Simcoe and Couchiching, See Name of Toronto | |||||

| Nickname(s): "Hogtown", "The Queen City", "The Big Smoke", "Toronto the Good"[1][1][2][3][4] | |||||

| Motto(s): Diversity Our Strength | |||||

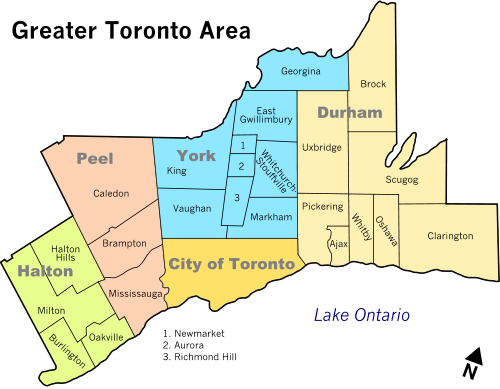

.svg.png) Location within the province of Ontario | |||||

Toronto Location within Canada  Toronto Location within Ontario  Toronto Location within North America | |||||

| Coordinates: 43°42′N 79°24′W / 43.700°N 79.400°WCoordinates: 43°42′N 79°24′W / 43.700°N 79.400°W | |||||

| Country | Canada | ||||

| Province | Ontario | ||||

| Districts | East York, Etobicoke, North York, Old Toronto, Scarborough, York | ||||

| Settled | 1750 (as Fort Rouillé)[5] | ||||

| Established | August 27, 1793 (as York) | ||||

| Incorporated | March 6, 1834 (as Toronto) | ||||

| Amalgamated into division | January 20, 1953 (as Metropolitan Toronto) | ||||

| Amalgamated | January 1, 1998 (as City of Toronto) | ||||

| Government | |||||

| • Type | Mayor–council | ||||

| • Mayor | John Tory | ||||

| • Deputy Mayor | Denzil Minnan-Wong | ||||

| • Council | Toronto City Council | ||||

| • MPs |

List of MPs

| ||||

| • MPPs |

List of MPPs

| ||||

| Area (2011)[6][7][8] | |||||

| • City (single-tier) | 630.21 km2 (243.33 sq mi) | ||||

| • Urban | 1,751.49 km2 (676.25 sq mi) | ||||

| • Metro | 5,905.71 km2 (2,280.21 sq mi) | ||||

| Elevation | 76 m (249 ft) | ||||

| Population (2016)[6][7][8] | |||||

| • City (single-tier) | 2,731,571 (1st) | ||||

| • Density | 4,334.4/km2 (11,226/sq mi) | ||||

| • Urban | 5,132,794 (1st) | ||||

| • Metro | 5,928,040 (1st) | ||||

| Demonym(s) | Torontonian | ||||

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) | ||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | ||||

| Postal code span | M | ||||

| Area code(s) | 416, 647, 437 | ||||

| NTS Map | 030M11 | ||||

| GNBC Code | FEUZB | ||||

| GDP | US$276.3 billion (2014)[9] | ||||

| GDP per capita | US$45,771 (2014)[9] | ||||

| Website |

toronto | ||||

Toronto (/təˈrɒntoʊ/ (![]()

People have travelled through and inhabited the Toronto area, situated on a broad sloping plateau interspersed with rivers, deep ravines, and urban forest, for more than 10,000 years.[13] After the broadly disputed Toronto Purchase, when the Mississauga surrendered the area to the British Crown,[14] the British established the town of York in 1793 and later designated it as the capital of Upper Canada.[15] During the War of 1812, the town was the site of the Battle of York and suffered heavy damage by United States troops.[16] York was renamed and incorporated in 1834 as the city of Toronto. It was designated as the capital of the province of Ontario in 1867 during Canadian Confederation.[17] The city proper has since expanded past its original borders through both annexation and amalgamation to its current area of 630.2 km2 (243.3 sq mi).

The diverse population of Toronto reflects its current and historical role as an important destination for immigrants to Canada.[18][19] More than 50 percent of residents belong to a visible minority population group,[20] and over 200 distinct ethnic origins are represented among its inhabitants.[21] While the majority of Torontonians speak English as their primary language, over 160 languages are spoken in the city.[22]

Toronto is a prominent centre for music,[23] theatre,[24] motion picture production,[25] and television production,[26] and is home to the headquarters of Canada's major national broadcast networks and media outlets.[27] Its varied cultural institutions,[28] which include numerous museums and galleries, festivals and public events, entertainment districts, national historic sites, and sports activities,[29] attract over 25 million tourists each year.[30][31] Toronto is known for its many skyscrapers and high-rise buildings,[32] in particular the tallest free-standing structure in the Western Hemisphere, the CN Tower.[33]

The city is home to the Toronto Stock Exchange, the headquarters of Canada's five largest banks,[34] and the headquarters of many large Canadian and multinational corporations.[35] Its economy is highly diversified with strengths in technology, design, financial services, life sciences, education, arts, fashion, business services, environmental innovation, food services, and tourism.[36][37][38]

History

Before 1800

When Europeans first arrived at the site of present-day Toronto, the vicinity was inhabited by the Iroquois,[39] who had displaced the Wyandot (Huron) people, occupants of the region for centuries before c. 1500.[40] The name Toronto is likely derived from the Iroquoian word tkaronto, meaning "place where trees stand in the water".[41] This refers to the northern end of what is now Lake Simcoe, where the Huron had planted tree saplings to corral fish. However, the word "Toronto", meaning "plenty" also appears in a 1632 French lexicon of the Huron language, which is also an Iroquoian language.[42] It also appears on French maps referring to various locations, including Georgian Bay, Lake Simcoe, and several rivers.[43] A portage route from Lake Ontario to Lake Huron running through this point, known as the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail, led to widespread use of the name.

In the 1660s, the Iroquois established two villages within what is today Toronto, Ganatsekwyagon on the banks of the Rouge River and Teiaiagon on the banks of the Humber River. By 1701, the Mississauga had displaced the Iroquois, who abandoned the Toronto area at the end of the Beaver Wars, with most returning to their base in present-day New York.[44]

French traders founded Fort Rouillé in 1750 (the current Exhibition grounds were later developed here), but abandoned it in 1759 due to the turbulence of the Seven Years' War.[45]

During the American Revolutionary War, an influx of British settlers came here as United Empire Loyalists fled for the British-controlled lands north of Lake Ontario. The Crown granted them land to compensate for their losses in the Thirteen Colonies. The new province of Upper Canada was being created and needed a capital. In 1787, the British Lord Dorchester arranged for the Toronto Purchase with the Mississauga of the New Credit First Nation, thereby securing more than a quarter of a million acres (1000 km2) of land in the Toronto area.[46] Dorchester intended the location to be named Toronto.[43]

In 1793, Governor John Graves Simcoe established the town of York on the Toronto Purchase lands, naming it after Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. Simcoe decided to move the Upper Canada capital from Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) to York,[47] believing that the new site would be less vulnerable to attack by the United States.[48] The York garrison was constructed at the entrance of the town's natural harbour, sheltered by a long sandbar peninsula. The town's settlement formed at the eastern end of the harbour behind the peninsula, near the present-day intersection of Parliament Street and Front Street (in the "Old Town" area).

1800–1899

In 1813, as part of the War of 1812, the Battle of York ended in the town's capture and plunder by United States forces.[49] The surrender of the town was negotiated by John Strachan. American soldiers destroyed much of the garrison and set fire to the parliament buildings during their five-day occupation. Because of the sacking of York, British troops retaliated later in the war with the Burning of Washington, DC.

York was incorporated as the City of Toronto on March 6, 1834, reverting to its original native name. Reformist politician William Lyon Mackenzie became the first Mayor of Toronto and led the unsuccessful Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837 against the British colonial government.

Toronto's population of 9,000 included African-American slaves, some of whom were brought by the Loyalists, including Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, and fewer Black Loyalists, whom the Crown had freed. (Most of the latter were resettled in Nova Scotia.) By 1834 refugee slaves from America's South were also immigrating to Toronto, settling in Canada to gain freedom.[50] Slavery was banned outright in Upper Canada (and throughout the British Empire) in 1834.[51] Torontonians integrated people of colour into their society. In the 1840s, an eating house at Frederick and King Streets, a place of mercantile prosperity in the early city, was operated by a man of colour named Bloxom.[52]

As a major destination for immigrants to Canada, the city grew rapidly through the remainder of the 19th century. The first significant wave of immigrants were Irish, fleeing the Great Irish Famine; most of them were Catholic. By 1851, the Irish-born population had become the largest single ethnic group in the city. Smaller numbers of Protestant Irish immigrants, some from what is now Northern Ireland, were welcomed by the existing Scottish and English population, giving the Orange Order significant and long-lasting influence over Toronto society.

For brief periods Toronto was twice the capital of the united Province of Canada: first from 1849 to 1852, following unrest in Montreal, and later 1856–1858. After this date, Quebec was designated as the capital until 1866 (one year before Canadian Confederation). Since then, the capital of Canada has remained Ottawa, Ontario.[53]

Toronto became the capital of the province of Ontario after its official creation in 1867. The seat of government of the Ontario Legislature is located at Queen's Park. Because of its provincial capital status, the city was also the location of Government House, the residence of the viceregal representative of the Crown in right of Ontario.

Long before the Royal Military College of Canada was established in 1876, supporters of the concept proposed military colleges in Canada. Staffed by British Regulars, adult male students underwent a three-month long military course at the School of Military Instruction in Toronto. Established by Militia General Order in 1864, the school enabled officers of militia or candidates for commission or promotion in the Militia to learn military duties, drill and discipline, to command a company at Battalion Drill, to drill a company at Company Drill, the internal economy of a company, and the duties of a company's officer.[54] The school was retained at Confederation, in 1867. In 1868, Schools of cavalry and artillery instruction were formed in Toronto.[55]

In the 19th century, the city built an extensive sewage system to improve sanitation, and streets were illuminated with gas lighting as a regular service. Long-distance railway lines were constructed, including a route completed in 1854 linking Toronto with the Upper Great Lakes. The Grand Trunk Railway and the Northern Railway of Canada joined in the building of the first Union Station in downtown. The advent of the railway dramatically increased the numbers of immigrants arriving, commerce and industry, as had the Lake Ontario steamers and schooners entering port before. These enabled Toronto to become a major gateway linking the world to the interior of the North American continent.

Toronto became the largest alcohol distillation (in particular, spirits) centre in North America. By the 1860s the Gooderham and Worts Distillery operations became the world's largest whiskey factory. A preserved section of this once dominant local industry remains in the Distillery District. The harbour allowed for sure access to grain and sugar imports used in processing. Expanding port and rail facilities brought in northern timber for export and imported Pennsylvania coal. Industry dominated the waterfront for the next 100 years.

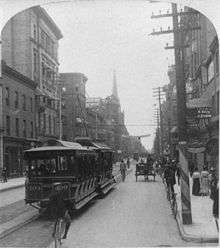

Horse-drawn streetcars gave way to electric streetcars in 1891, when the city granted the operation of the transit franchise to the Toronto Railway Company. The public transit system passed into public ownership in 1921 as the Toronto Transportation Commission, later renamed the Toronto Transit Commission. The system now has the third-highest ridership of any city public transportation system in North America.[56]

Since 1900

The Great Toronto Fire of 1904 destroyed a large section of downtown Toronto, but the city was quickly rebuilt. The fire caused more than $10 million in damage, and resulted in more stringent fire safety laws and expansion of the city's fire department.

The city received new European immigrant groups beginning in the late 19th century into the early 20th century, particularly Germans, French, Italians, and Jews from various parts of Eastern Europe. They were soon followed by Russians, Poles, and other Eastern European nations, in addition to Chinese entering from the West. As the Irish before them, many of these new migrants lived in overcrowded shanty-type slums, such as "the Ward" which was centred on Bay Street, now the heart of the country's Financial District. As new migrants began to prosper, they moved to better housing in other areas, in what is now understood to be succession waves of settlement. Despite its fast-paced growth, by the 1920s, Toronto's population and economic importance in Canada remained second to the much longer established Montreal, Quebec. However, by 1934, the Toronto Stock Exchange had become the largest in the country.

Following the Second World War, refugees from war-torn Europe and Chinese job-seekers arrived, as well as construction labourers, particularly from Italy and Portugal. Toronto's population grew to more than one million in 1951 when large-scale suburbanization began, and doubled to two million by 1971. Following the elimination of racially based immigration policies by the late 1960s, Toronto became a destination for immigrants from all parts of the world.

By the 1980s, Toronto had surpassed Montreal as Canada's most populous city and chief economic hub. During this time, in part owing to the political uncertainty raised by the resurgence of the Quebec sovereignty movement, many national and multinational corporations moved their head offices from Montreal to Toronto and Western Canadian cities.[57]

In 1954, the City of Toronto and 12 surrounding municipalities were federated into a regional government known as Metropolitan Toronto.[58] The postwar boom had resulted in rapid suburban development and it was believed that a coordinated land-use strategy and shared services would provide greater efficiency for the region. The metropolitan government began to manage services that crossed municipal boundaries, including highways, police services, water and public transit.

In that year, a half-century after the Great Fire of 1904, disaster struck the city again when Hurricane Hazel brought intense winds and flash flooding. In the Toronto area, 81 people were killed, nearly 1,900 families were left homeless, and the hurricane caused more than $25 million in damage.[59]

In 1967, the seven smallest municipalities of Metropolitan Toronto were merged with larger neighbours, resulting in a six-municipality configuration that included the former city of Toronto and the surrounding municipalities of East York, Etobicoke, North York, Scarborough, and York.[60]

In 1998, the Conservative provincial government led by Mike Harris dissolved the metropolitan government, despite vigorous opposition from the component municipalities and overwhelming rejection in a municipal plebiscite. All six municipalities were amalgamated into a single municipality, creating the current City of Toronto, the successor of the old City of Toronto. North York mayor Mel Lastman became the first "megacity" mayor and the 62nd Mayor of Toronto. John Tory is the current mayor.

The city attracted international attention in 2003 when it became the centre of a major SARS outbreak. Public health attempts to prevent the disease from spreading elsewhere temporarily dampened the local economy.[61]

On March 6, 2009, the city celebrated the 175th anniversary of its inception as the City of Toronto in 1834. Toronto hosted the 4th G20 summit during June 26–27, 2010. This included the largest security operation in Canadian history. Following large-scale protests and rioting, law enforcement conducted the largest mass arrest (more than a thousand people) in Canadian history.[62]

On July 8, 2013, severe flash flooding hit Toronto after an afternoon of slow moving, intense thunderstorms. Toronto Hydro estimated that 450,000 people were without power after the storm and Toronto Pearson International Airport reported that 126 mm (5 in) of rain had fallen over five hours, more than during Hurricane Hazel.[63] Within six months, on December 20, 2013, Toronto was brought to a halt by the worst ice storm in the city's history, rivaling the severity of the 1998 Ice Storm. Toronto hosted WorldPride in June 2014[64] and the Pan American Games in 2015.[65]

On April 23, 2018, a van attack by a lone perpetrator killed ten people in the North York City Centre within Toronto's northern district. On July 22 of the same year, there was a mass shooting in the Danforth neighbourhood that killed two people; police later shot the perpetrator dead.

Geography

Toronto covers an area of 630 square kilometres (243 sq mi),[66] with a maximum north-south distance of 21 kilometres (13 mi) and a maximum east-west distance of 43 km (27 mi). It has a 46-kilometre (29 mi) long waterfront shoreline, on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario. The Toronto Islands and Port Lands extend out into the lake, allowing for a somewhat sheltered Toronto Harbour south of the downtown core.[67] The city's borders are formed by Lake Ontario to the south, Etobicoke Creek and Highway 427 to the west, Steeles Avenue to the north and the Rouge River and the Toronto-Pickering Townline to the east.

Topography

The city is mostly flat or gentle hills and the land gently slopes upward away from the lake. The flat land is interrupted by numerous ravines cut by numerous creeks and the valleys of the three rivers in Toronto: the Humber River in the west end and the Don River east of downtown at opposite ends of Toronto Harbour, and the Rouge River at the city's eastern limits. Most of the ravines and valley lands in Toronto today are parklands, and recreational trails are laid out along the ravines and valleys. The original town was laid out in a grid plan on the flat plain north of the harbour, and this plan was extended outwards as the city grew. The width and depth of several of the ravines and valleys are such that several grid streets such as Finch Avenue, Leslie Street, Lawrence Avenue, and St. Clair Avenue, terminate on one side of a ravine or valley and continue on the other side. Toronto has many bridges spanning the ravines. Large bridges such as the Prince Edward Viaduct were built to span wide river valleys.

Despite its deep ravines, Toronto is not remarkably hilly, but its elevation does increase steadily away from the lake. Elevation differences range from 75 metres (246 ft) above sea level at the Lake Ontario shore to 209 m (686 ft) ASL near the York University grounds in the city's north end at the intersection of Keele Street and Steeles Avenue.[68] There are occasional hilly areas; in particular, midtown Toronto has a number of sharply sloping hills. Lake Ontario remains occasionally visible from the peaks of these ridges as far north as Eglinton Avenue, 7 to 8 kilometres (4.3 to 5.0 mi) inland.

.jpg)

The other major geographical feature of Toronto is its escarpments. During the last ice age, the lower part of Toronto was beneath Glacial Lake Iroquois. Today, a series of escarpments mark the lake's former boundary, known as the "Iroquois Shoreline". The escarpments are most prominent from Victoria Park Avenue to the mouth of Highland Creek where they form the Scarborough Bluffs. Other observable sections include the area near St. Clair Avenue West between Bathurst Street and the Don River, and north of Davenport Road from Caledonia to Spadina Road; the Casa Loma grounds sit above this escarpment.

The geography of the lake shore is greatly changed since the first settlement of Toronto. Much of the land on the north shore of the harbour is landfill, filled in during the late 19th century. Until then, the lakefront docks (then known as wharves) were set back farther inland than today. Much of the adjacent Port Lands on the east side of the harbour was a wetland filled in early in the 20th century. The shoreline from the harbour west to the Humber River has been extended into the lake. Further west, landfill has been used to create extensions of land such as Humber Bay Park.

The Toronto Islands were a natural peninsula until a storm in 1858 severed their connection to the mainland,[69] creating a channel to the harbour. The peninsula was formed by longshore drift taking the sediments deposited along the Scarborough Bluffs shore and transporting them to the Islands area. The other source of sediment for the Port Lands wetland and the peninsula was the deposition of the Don River, which carved a wide valley through the sedimentary land of Toronto and deposited it in the harbour, which is quite shallow. The harbour and the channel of the Don River have been dredged numerous times for shipping. The lower section of the Don River was straightened and channelled in the 19th century. The former mouth drained into a wetland; today the Don drains into the harbour through a concrete waterway, the Keating Channel.

Climate

The city of Toronto has a hot summer humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfa) bordering on a warm summer humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb), with warm, humid summers and cold winters.[70]

| Toronto | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The city experiences four distinct seasons, with considerable variance in length.[72] Some parts of the north and east of the city such as Scarborough and the suburbs, have a climate classified as humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb). As a result of the rapid passage of weather systems (such as high- and low-pressure systems), the weather is variable from day to day in all seasons.[72] Owing to urbanization and its proximity to water, Toronto has a fairly low diurnal temperature range. The denser urbanscape makes for warmer nights year around; the average nighttime temperature is about 3.0 °C (5.40 °F) warmer in the city than in rural areas in all months.[73] However, it can be noticeably cooler on many spring and early summer afternoons under the influence of a lake breeze since Lake Ontario is cool, relative to the air during these seasons.[73] These lake breezes mostly occur in summer, bringing relief on hot days.[73] Other low-scale maritime effects on the climate include lake-effect snow, fog, and delaying of spring- and fall-like conditions, known as seasonal lag.[73]

Winters are cold with frequent snow.[74] During the winter months, temperatures are usually below 0 °C (32 °F).[74] Toronto winters sometimes feature cold snaps when maximum temperatures remain below −10 °C (14 °F), often made to feel colder by wind chill. Occasionally, they can drop below −25 °C (−13 °F).[74] Snowstorms, sometimes mixed with ice and rain, can disrupt work and travel schedules, while accumulating snow can fall anytime from November until mid-April. However, mild stretches also occur in most winters, melting accumulated snow. The summer months are characterized by very warm temperatures.[74] Daytime temperatures are usually above 20 °C (68 °F), and often rise above 30 °C (86 °F).[74] However, they can occasionally surpass 35 °C (95 °F) accompanied by high humidity. Spring and autumn are transitional seasons with generally mild or cool temperatures with alternating dry and wet periods.[73] Daytime temperatures average around 10 to 12 °C (50 to 54 °F) during these seasons.[74]

Precipitation is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year, but summer is usually the wettest season, the bulk falling during thunderstorms. There can be periods of dry weather, but drought-like conditions are rare. The average yearly precipitation is about 831 mm (32.7 in), with an average annual snowfall of about 122 cm (48 in).[75] Toronto experiences an average of 2,066 sunshine hours, or 45% of daylight hours, varying between a low of 28% in December to 60% in July.[75]

According to the classification applied by Natural Resources Canada, Toronto is located in plant hardiness zones 5b to 7a.[76][77]

| Climate data for Toronto (The Annex), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1840–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61) |

19.1 (66.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

32.2 (90) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.7 (98.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

38.9 (102) |

37.8 (100) |

30.8 (87.4) |

23.9 (75) |

19.9 (67.8) |

40.6 (105.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.7 (25.3) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.4 (34.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.3 (72.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

17.2 (63) |

10.7 (51.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.7 (19.9) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.8 (−27) |

−31.7 (−25.1) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−15.0 (5) |

−3.9 (25) |

−2.2 (28) |

3.9 (39) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−2.2 (28) |

−8.9 (16) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−30.0 (−22) |

−32.8 (−27) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 61.5 (2.421) |

55.4 (2.181) |

53.7 (2.114) |

68.0 (2.677) |

82.0 (3.228) |

70.9 (2.791) |

63.9 (2.516) |

81.1 (3.193) |

84.7 (3.335) |

64.4 (2.535) |

84.1 (3.311) |

61.5 (2.421) |

831.1 (32.72) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 29.1 (1.146) |

29.7 (1.169) |

33.6 (1.323) |

61.1 (2.406) |

82.0 (3.228) |

70.9 (2.791) |

63.9 (2.516) |

81.1 (3.193) |

84.7 (3.335) |

64.3 (2.531) |

75.4 (2.969) |

38.2 (1.504) |

714.0 (28.11) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 37.2 (14.65) |

27.0 (10.63) |

19.8 (7.8) |

5.0 (1.97) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.1 (0.04) |

8.3 (3.27) |

24.1 (9.49) |

121.5 (47.83) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 15.4 | 11.6 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 11.0 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 13.0 | 13.2 | 145.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.4 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 11.0 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 10.9 | 7.0 | 114.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 12.0 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.08 | 3.1 | 8.4 | 40.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 85.9 | 111.3 | 161.0 | 180.0 | 227.7 | 259.6 | 279.6 | 245.6 | 194.4 | 154.3 | 88.9 | 78.1 | 2,066.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 29.7 | 37.7 | 43.6 | 44.8 | 50.0 | 56.3 | 59.8 | 56.7 | 51.7 | 45.1 | 30.5 | 28.0 | 44.5 |

| Source: Environment Canada [75][82][83] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture

.jpg)

Lawrence Richards, a member of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Toronto, has said: "Toronto is a new, brash, rag-tag place—a big mix of periods and styles."[84] Toronto's buildings vary in design and age with many structures dating back to the early-19th-century, while other prominent buildings were just newly built in the first decade of the 21st century. Bay-and-gable houses, mainly found in Old Toronto, are a distinct architectural feature of the city. Defining the Toronto skyline is the CN Tower, a telecommunications and tourism hub. Completed in 1976 at a height of 553.33 metres (1,815 ft 5 in), it was the world's tallest[85] freestanding structure until 2007 when it was surpassed by Burj Khalifa.[86]

Toronto is a city of high-rises, having 1,800 buildings over 30 metres (98 ft).[87]

Through the 1960s and 1970s, significant pieces of Toronto's architectural heritage were demolished to make way for redevelopment or parking. In contrast, since the 2000s, Toronto has experienced a period of architectural revival, with several buildings by world-renowned architects having opened during the late 2000s. Daniel Libeskind's Royal Ontario Museum addition, Frank Gehry's remake of the Art Gallery of Ontario, and Will Alsop's distinctive Ontario College of Art & Design expansion are among the city's new showpieces.[88] The historic Distillery District, located on the eastern edge of downtown has been redeveloped into a pedestrian-oriented arts, culture and entertainment neighbourhood.[89]

Neighbourhoods

Toronto encompasses a geographical area formerly administered by many separate municipalities. These municipalities have each developed a distinct history and identity over the years, and their names remain in common use among Torontonians. Former municipalities include East York, Etobicoke, Forest Hill, Mimico, North York, Parkdale, Scarborough, Swansea, Weston and York. Throughout the city there exist hundreds of small neighbourhoods and some larger neighbourhoods covering a few square kilometres.

The many residential communities of Toronto express a character distinct from that of the skyscrapers in the commercial core. Victorian and Edwardian-era residential buildings can be found in enclaves such as Rosedale, Cabbagetown, The Annex, and Yorkville. The Wychwood Park neighbourhood, historically significant for the architecture of its homes, and for being one of Toronto's earliest planned communities, was designated as an Ontario Heritage Conservation district in 1985.[90] The Casa Loma neighbourhood is named after "Casa Loma", a castle built in 1911 by Sir Henry Pellat, complete with gardens, turrets, stables, an elevator, secret passages, and a bowling alley.[91] Spadina House is a 19th-century manor that is now a museum.[92]

Old Toronto

The pre-amalgamation City of Toronto covers the area generally known as downtown, but also older neighbourhoods to the east, west, and north of downtown. It includes the core of Toronto and remains the most densely populated part of the city. The Financial District contains the First Canadian Place, Toronto–Dominion Centre, Scotia Plaza, Royal Bank Plaza, Commerce Court and Brookfield Place. This area includes, among others, the neighbourhoods of St. James Town, Garden District, St. Lawrence, Corktown, and Church and Wellesley. From that point, the Toronto skyline extends northward along Yonge Street.

Old Toronto is also home to many historically wealthy residential enclaves, such as Yorkville, Rosedale, The Annex, Forest Hill, Lawrence Park, Lytton Park, Deer Park, Moore Park, and Casa Loma, most stretching away from downtown to the north. East and west of downtown, neighbourhoods such as Kensington Market, Chinatown, Leslieville, Cabbagetown and Riverdale are home to bustling commercial and cultural areas as well as communities of artists with studio lofts, with many middle- and upper-class professionals. Other neighbourhoods in the central city retain an ethnic identity, including two smaller Chinatowns, the Greektown area, Little Italy, Portugal Village, and Little India, along with others.

Suburbs

The inner suburbs are contained within the former municipalities of York and East York. These are mature and traditionally working-class areas, consisting primarily of post–World War I small, single-family homes and small apartment blocks. Neighbourhoods such as Crescent Town, Thorncliffe Park, Weston, and Oakwood–Vaughan consist mainly of high-rise apartments, which are home to many new immigrant families. During the 2000s, many neighbourhoods have become ethnically diverse and have undergone gentrification as a result of increasing population, and a housing boom during the late 1990s and first two decades of the 21st century. The first neighbourhoods affected were Leaside and North Toronto, gradually progressing into the western neighbourhoods in York. Some of the area's housing is in the process of being replaced or remodelled.

.jpg)

The outer suburbs comprising the former municipalities of Etobicoke (west), Scarborough (east) and North York (north) largely retain the grid plan laid before post-war development. Sections were long established and quickly growing towns before the suburban housing boom began and the emergence of metropolitan government, existing towns or villages such as Mimico, Islington and New Toronto in Etobicoke; Willowdale, Newtonbrook and Downsview in North York; Agincourt, Wexford and West Hill in Scarborough where suburban development boomed around or between these and other towns beginning in the late 1940s. Upscale neighbourhoods were built such as the Bridle Path in North York, the area surrounding the Scarborough Bluffs in Guildwood, and most of central Etobicoke, such as Humber Valley Village, and The Kingsway. One of largest and earliest "planned communities" was Don Mills, parts of which were first built in the 1950s.[93] Phased development, mixing single-detached housing with higher-density apartment blocks, became more popular as a suburban model of development. Over the late 20th century and early 21st century, North York City Centre, Etobicoke City Centre and Scarborough City Centre have emerged as secondary business districts outside Downtown Toronto. High-rise development in these areas has given the former municipalities distinguishable skylines of their own with high-density transit corridors serving them.

Industrial

In the 1800s, a thriving industrial area developed around Toronto Harbour and lower Don River mouth, linked by rail and water to Canada and the United States. Examples included the Gooderham and Worts Distillery, Canadian Malting Company, the Toronto Rolling Mills, the Union Stockyards and the Davies pork processing facility (the inspiration for the "Hogtown" nickname). This industrial area expanded west along the harbour and rail lines and was supplemented by the infilling of the marshlands on the east side of the harbour to create the Port Lands. A garment industry developed along lower Spadina Avenue, the "Fashion District". Beginning in the late 19th century, industrial areas were set up on the outskirts, such as West Toronto/The Junction, where the Stockyards relocated in 1903.[94] The Great Fire of 1904 destroyed a large amount of industry in the downtown. Some of the companies moved west along King Street, some as far west as Dufferin Street; where the large Massey-Harris farm equipment manufacturing complex was located.[95] Over time, pockets of industrial land mostly followed rail lines and later highway corridors as the city grew outwards. This trend continues to this day, the largest factories and distribution warehouses are located in the suburban environs of Peel and York Regions; but also within the current city: Etobicoke (concentrated around Pearson Airport), North York, and Scarborough.

.jpg)

Many of Toronto's former industrial sites close to (or in) Downtown have been redeveloped including parts of the Toronto waterfront, the rail yards west of downtown, and Liberty Village, the Massey-Harris district and large-scale development is underway in the West Don Lands. The Gooderham & Worts Distillery produced spirits until 1990, and is preserved today as the "Distillery District," the largest and best-preserved collection of Victorian industrial architecture in North America.[96] Some industry remains in the area, including the Redpath Sugar Refinery. Similar areas that still retain their industrial character, but are now largely residential are the Fashion District, Corktown, and parts of South Riverdale and Leslieville. Toronto still has some active older industrial areas, such as Brockton Village, Mimico and New Toronto. In the west end of Old Toronto and York, the Weston/Mount Dennis and The Junction areas still contain factories, meat-packing facilities and rail yards close to medium-density residential, although the Junction's Union Stockyards moved out of Toronto in 1994.[94]

The "brownfield" industrial area of the Port Lands, on the east side of the harbour, is one area planned for redevelopment.[97] Formerly a marsh that was filled in to create industrial space, it was never intensely developed, its land unsuitable for large-scale development, because of flooding and unstable soil.[98] It still contains numerous industrial uses, such as the Portlands Energy Centre power plant, some port facilities, some movie and TV production studios, a concrete processing facility and various low-density industrial facilities. The Waterfront Toronto agency has developed plans for a naturalized mouth to the Don River and to create a flood barrier around the Don, making more of the land on the harbour suitable for higher-value residential and commercial development.[99] A former chemicals plant site along the Don River is slated to become a large commercial complex and transportation hub.[100]

Public spaces

Toronto has a diverse array of public spaces, from city squares to public parks overlooking ravines. Nathan Phillips Square is the city's main square in downtown, and forms the entrance to City Hall. Yonge-Dundas Square, near City Hall, has also gained attention in recent years as one of the busiest gathering spots in the city. Other squares include Harbourfront Square, on the Toronto waterfront, and the civic squares at the former city halls of the defunct Metropolitan Toronto, most notably Mel Lastman Square in North York. The Toronto Public Space Committee is an advocacy group concerned with the city's public spaces. In recent years, Nathan Phillips Square has been refurbished with new facilities, and the central waterfront along Queen's Quay West has been updated recently with a new street architecture and a new square next to Harbourfront Centre.

In the winter, Nathan Phillips Square, Harbourfront Centre, and Mel Lastman Square feature popular rinks for public ice-skating. Etobicoke's Colonel Sam Smith Trail opened in 2011 and is Toronto's first skating trail. Centennial Park and Earl Bales Park offer outdoor skiing and snowboarding slopes with a chairlift, rental facilities, and lessons. Several parks have marked cross-country skiing trails.

There are many large downtown parks, which include Allan Gardens, Christie Pits, Grange Park, Little Norway Park, Moss Park, Queen's Park, Riverdale Park and Trinity Bellwoods Park. An almost hidden park is the compact Cloud Gardens,[101] which has both open areas and a glassed-in greenhouse, near Queen and Yonge. South of downtown are two large parks on the waterfront: Tommy Thompson Park on the Leslie Street Spit, which has a nature preserve, is open on weekends; and the Toronto Islands, accessible from downtown by ferry.

Large parks in the outer areas managed by the city include High Park, Humber Bay Park, Centennial Park, Downsview Park, Guild Park and Gardens, and Morningside Park. Toronto also operates several public golf courses. Most ravine lands and river bank floodplains in Toronto are public parklands. After Hurricane Hazel in 1954, construction of buildings on floodplains was outlawed, and private lands were bought for conservation. In 1999, Downsview Park, a former military base in North York, initiated an international design competition to realize its vision of creating Canada's first urban park. The winner, "Tree City", was announced in May 2000. Approximately 8,000 hectares (20,000 acres), or 12.5 percent of Toronto's land base is maintained parkland.[102] Morningside Park is the largest park managed by the city, which is 241.46 hectares (596.7 acres) in size.[102]

In addition to public parks managed by the municipal government, parts of Rouge National Urban Park, the largest urban park in North America, is located in the eastern portion of Toronto. Managed by Parks Canada, the national park is centred around the Rouge River, and encompasses several municipalities in the Greater Toronto Area.[103]

Culture

Toronto theatre and performing arts scene has more than fifty ballet and dance companies, six opera companies, two symphony orchestras and a host of theatres. The city is home to the National Ballet of Canada, the Canadian Opera Company, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the Canadian Electronic Ensemble, and the Canadian Stage Company. Notable performance venues include the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, Roy Thomson Hall, the Princess of Wales Theatre, the Royal Alexandra Theatre, Massey Hall, the Toronto Centre for the Arts, the Elgin and Winter Garden Theatres and the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts (originally the "O'Keefe Centre" and formerly the "Hummingbird Centre").

Ontario Place features the world's first permanent IMAX movie theatre, the Cinesphere,[104] as well as the Budweiser Stage, an open-air venue for music concerts. In spring 2012, Ontario Place closed after a decline in attendance over the years. Although the Molson Amphitheatre and harbour still operate, the park and Cinesphere are no longer in use. There are ongoing plans to revitalise Ontario Place.[105]

Each summer, the Canadian Stage Company presents an outdoor Shakespeare production in Toronto's High Park called "Dream in High Park". Canada's Walk of Fame acknowledges the achievements of successful Canadians, with a series of stars on designated blocks of sidewalks along King Street and Simcoe Street.

The production of domestic and foreign film and television is a major local industry. Toronto as of 2011 ranks as the third largest production centre for film and television after Los Angeles and New York City,[106] sharing the nickname "Hollywood North" with Vancouver.[107][108][109] The Toronto International Film Festival is an annual event celebrating the international film industry. Another prestigious film festival is the Toronto Student Film Festival, that screens the works of students ages 12–18 from many different countries across the globe.

Toronto's Caribana (formerly known as Scotiabank Caribbean Carnival) takes place from mid-July to early August of every summer.[110] Primarily based on the Trinidad and Tobago Carnival, the first Caribana took place in 1967 when the city's Caribbean community celebrated Canada's Centennial. More than forty years later, it has grown to attract one million people to Toronto's Lake Shore Boulevard annually. Tourism for the festival is in the hundred thousands, and each year, the event generates over $400 million in revenue into Ontario's economy.[111]

One of the largest events in the city, Pride Week takes place in late June, and is one of the largest LGBT festivals in the world.

Media

Toronto is Canada's largest media market,[112] and has four conventional dailies, two alt-weeklies, and three free commuter papers in a greater metropolitan area of about 6 million inhabitants. The Toronto Star and the Toronto Sun are the prominent daily city newspapers, while national dailies The Globe and Mail and the National Post are also headquartered in the city. The Toronto Star, The Globe and Mail, and National Post are broadsheet newspapers. Metro and 24 Hours are distributed as free commuter newspapers. Several magazines and local newspapers cover Toronto, including Now and Toronto Life, while numerous magazines are produced in Toronto, such as Canadian Business, Chatelaine, Flare and Maclean's.

Toronto contains the headquarters of the major English-language Canadian television networks CBC, CTV, Citytv, Global, The Sports Network (TSN) and Sportsnet. Much (formerly MuchMusic), M3 (formerly MuchMore) and MTV Canada are the main music television channels based in the city, though they no longer primarily show music videos as a result of channel drift.

Tourism

The Royal Ontario Museum is a museum of world culture and natural history. The Toronto Zoo,[113][114] is home to over 5,000 animals representing over 460 distinct species. The Art Gallery of Ontario contains a large collection of Canadian, European, African and contemporary artwork, and also plays host to exhibits from museums and galleries all over the world. The Gardiner Museum of ceramic art is the only museum in Canada entirely devoted to ceramics, and the Museum's collection contains more than 2,900 ceramic works from Asia, the Americas, and Europe. The city also hosts the Ontario Science Centre, the Bata Shoe Museum, and Textile Museum of Canada.

Other prominent art galleries and museums include the Design Exchange, the Museum of Inuit Art, the TIFF Bell Lightbox, the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto Canada, the Institute for Contemporary Culture, the Toronto Sculpture Garden, the CBC Museum, the Redpath Sugar Museum, the University of Toronto Art Centre, Hart House, the TD Gallery of Inuit Art and the Aga Khan Museum. The city also runs its own museums, which include the Spadina House.

The Don Valley Brick Works is a former industrial site that opened in 1889, and was partly restored as a park and heritage site in 1996, with further restoration and reuse being completed in stages since then. The Canadian National Exhibition ("The Ex") is held annually at Exhibition Place, and it is the oldest annual fair in the world. The Ex has an average attendance of 1.25 million.[115]

City shopping areas include the Yorkville neighbourhood, Queen West, Harbourfront, the Entertainment District, the Financial District, and the St. Lawrence Market neighbourhood. The Eaton Centre is Toronto's most popular tourist attraction with over 52 million visitors annually.[116]

Greektown on the Danforth is home to the annual "Taste of the Danforth" festival which attracts over one million people in 2½ days.[117] Toronto is also home to Casa Loma, the former estate of Sir Henry Pellatt, a prominent Toronto financier, industrialist and military man. Other notable neighbourhoods and attractions include The Beaches, the Toronto Islands, Kensington Market, Fort York, and the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Sports

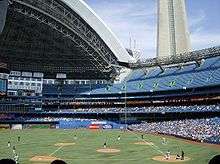

Toronto is represented in six major league sports, with teams in the National Hockey League, Major League Baseball, National Basketball Association, Canadian Football League, Major League Soccer and Canadian Women's Hockey League. It was formerly represented in a seventh, the USL W-League, until that announced on November 6, 2015 that it would cease operation ahead of 2016 season.[118][119] The city's major sports venues include the Scotiabank Arena, Rogers Centre (formerly SkyDome), Coca-Cola Coliseum, and BMO Field.

Professional sports

Toronto is home to the Toronto Maple Leafs, one of the National Hockey League's Original Six clubs, and has also served as home to the Hockey Hall of Fame since 1958. The city had a rich history of ice hockey championships. Along with the Maple Leafs' 13 Stanley Cup titles, the Toronto Marlboros and St. Michael's College School-based Ontario Hockey League teams, combined, have won a record 12 Memorial Cup titles. The Toronto Marlies of the American Hockey League also play in Toronto at Coca-Cola Coliseum and are the farm team for the Maple Leafs.

The city is home to the Toronto Blue Jays professional baseball team of Major League Baseball (MLB). The team has won two World Series titles (1992, 1993). The Blue Jays play their home games at the Rogers Centre, in the downtown core. Toronto has a long history of minor-league professional baseball dating back to the 1800s, culminating in the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team, whose owner first proposed an MLB team for Toronto.

The Toronto Raptors entered the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 1995, and have since earned seven playoff spots and three Atlantic Division titles in 20 seasons. The Raptors are the only NBA team with their own television channel, NBA TV Canada. They and the Maple Leafs play their home games at the Scotiabank Arena. In 2016, Toronto hosted the 65th NBA All-Star game, the first to be held outside the United States.[120]

The city is represented in the Canadian Football League by the Toronto Argonauts, who have won 17 Grey Cup titles.

Toronto is represented in Major League Soccer by the Toronto FC, who have won six Canadian Championship titles, as well as the MLS Cup in 2017. They share BMO Field with the Toronto Argonauts. Toronto has a high level of participation in soccer across the city at several smaller stadiums and fields. Toronto FC entered the league as an expansion team.

The Toronto Rock are the city's National Lacrosse League team. They won five National Lacrosse League Cup titles in seven years in the late 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century, appearing in an NLL record five straight championship games from 1999 to 2003, and are currently first all-time in the number of Champion's Cups won. The Rock share the Scotiabank Arena with the Maple Leafs and the Raptors.

Toronto has hosted several National Football League exhibition games at the Rogers Centre. Ted Rogers leased the Buffalo Bills from Ralph Wilson for the purposes of having the Bills play eight home games in the city between 2008 and 2013. Toronto was home to the International Bowl, an NCAA sanctioned post-season football game that pitted a Mid-American Conference team against a Big East Conference team. From 2007 to 2010, the game was played at Rogers Centre annually in January.

The Toronto Wolfpack became Canada's first professional rugby league team and the world's first transatlantic professional sports team when they began play in the Rugby Football League's League One competition in 2017.[121]

Toronto is home to the Toronto Rush, a semi-professional ultimate team that competes in the American Ultimate Disc League (AUDL).[122][123] Ultimate (disc), in Canada, has its beginning roots in Toronto, with 3300 players competing annually in the Toronto Ultimate Club (League).[124]

Events

Toronto, along with Montreal, hosts an annual tennis tournament called the Canadian Open (not to be confused with the identically named golf tournament) between the months of July and August. In odd-numbered years, the men's tournament is held in Montreal, while the women's tournament is held in Toronto, and vice versa in even-numbered years.

The city hosts the annual Honda Indy Toronto car race, part of the IndyCar Series schedule, held on a street circuit at Exhibition Place. It was known previously as the Champ Car's Molson Indy Toronto from 1986 to 2007. Both thoroughbred and standardbred horse racing events are conducted at Woodbine Racetrack in Rexdale.

Toronto hosted the 2015 Pan American Games in July 2015, and the 2015 Parapan American Games in August 2015. It beat the cities of Lima, Peru and Bogotá, Colombia, to win the rights to stage the games.[125] The games were the largest multi-sport event ever to be held in Canada (in terms of athletes competing), double the size of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, British Columbia.[126]

Toronto was a candidate city for the 1996 and 2008 Summer Olympics, which were awarded to Atlanta and Beijing respectively.[127]

Historic sports clubs of Toronto include the Granite Club (established in 1836), the Royal Canadian Yacht Club (established in 1852), the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club (established before 1827), the Argonaut Rowing Club (established in 1872), the Toronto Lawn Tennis Club (established in 1881), and the Badminton and Racquet Club (established in 1924).

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto Argonauts | CFL | Football | BMO Field | 1873 | 17 (Last in 2017) |

| Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | Ice hockey | Scotiabank Arena | 1917 | 13 (Last in 1967) |

| Toronto Blue Jays | MLB | Baseball | Rogers Centre | 1977 | 2 (Last in 1993) |

| Toronto Raptors | NBA | Basketball | Scotiabank Arena | 1995 | 0 |

| Toronto FC | MLS | Soccer | BMO Field | 2007 | 1 (Last in 2017) |

| Toronto Wolfpack | Championship | Rugby league | Lamport Stadium | 2017 | 1 (in 2017 League 1) |

| Toronto Maple Leafs | IBL | Baseball | Christie Pits | 1969 | 8 |

| Toronto Rock | NLL | Box lacrosse | Scotiabank Arena | 1998 | 6 (last in 2011) |

| Toronto Marlies | AHL | Ice hockey | Coca-Cola Coliseum | 2005 | 1 (last in 2018) |

| Toronto Furies | CWHL | Women's ice hockey | Mastercard Centre | 2007 | 1 |

| Toronto Lady Lynx | USL | Women's soccer | Centennial Park Stadium | 2005 | 0 |

| Toronto Eagles | AFLO | Australian Football | Humber College North | 1989 | 12 |

| Toronto Rush | AUDL | Ultimate | Varsity Stadium | 2013 | 1 |

Economy

Toronto is an international centre for business and finance. Generally considered the financial capital of Canada, Toronto has a high concentration of banks and brokerage firms on Bay Street, in the Financial District. The Toronto Stock Exchange is the world's seventh-largest stock exchange by market capitalization.[128] The five largest financial institutions of Canada, collectively known as the Big Five, have national offices in Toronto.[36]

The city is an important centre for the media, publishing, telecommunication, information technology and film production industries; it is home to Bell Media, Rogers Communications, and Torstar. Other prominent Canadian corporations in the Greater Toronto Area include Magna International, Celestica, Manulife, Sun Life Financial, the Hudson's Bay Company, and major hotel companies and operators, such as Four Seasons Hotels and Fairmont Hotels and Resorts.

Although much of the region's manufacturing activities take place outside the city limits, Toronto continues to be a wholesale and distribution point for the industrial sector. The city's strategic position along the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor and its road and rail connections help support the nearby production of motor vehicles, iron, steel, food, machinery, chemicals and paper. The completion of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959 gave ships access to the Great Lakes from the Atlantic Ocean.

Toronto's unemployment rate was 6.7% as of July 2016.[129] According to the website Numbeo, Toronto's cost of living plus rent index was second highest in Canada (of 31 cities).[130] The local purchasing power was the sixth lowest in Canada, mid-2017.[131] The average monthly social assistance caseload for January to October 2014 was 92,771. The number of seniors living in poverty increased from 10.5% in 2011 to 12.1% in 2014. Toronto's 2013 child poverty rate was 28.6%, the highest among large Canadian cities of 500,000 or more residents.[132]

Demographics

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

The city's population grew by 4% (96,073 residents) between 1996 and 2001, 1% (21,787 residents) between 2001 and 2006, 4.3% (111,779 residents) between 2006 and 2011, and 4.5% (116,511) between 2011 and 2016.[133] In 2016, persons aged 14 years and under made up 14.5% of the population, and those aged 65 years and over made up 15.6%.[133] The median age was 39.3 years.[133] The city's gender population is 48% male and 52% female.[133] Women outnumber men in all age groups 15 and older.[133]

In 2016, foreign-born persons made up 47.5% of the population,[20] compared to 49.9% in 2006.[134] According to the United Nations Development Programme, Toronto has the second-highest percentage of constant foreign-born population among world cities, after Miami, Florida. While Miami's foreign-born population has traditionally consisted primarily of Cubans and other Latin Americans, no single nationality or culture dominates Toronto's immigrant population, placing it among the most diverse cities in the world.[134] In 2010, it was estimated that over 100,000 immigrants arrive in the Greater Toronto Area annually.[135]

Ethnicity

In 2016, the three most commonly reported ethnic origins overall were Chinese (332,830 or 12.5%), English (331,890 or 12.3%) and Canadian (323,175 or 12.0%).[20] Common regions of ethnic origin were European (47.9%), Asian (including middle-Eastern – 40.1%), African (5.5%), Latin/Central/South American (4.2%), and North American aboriginal (1.2%).[20]

In 2016, 51.5% of the residents of the city proper belonged to a visible minority group, compared to 49.1% in 2011,[20][136] and 13.6% in 1981.[137] The largest visible minority groups were South Asian (338,960 or 12.6%), Chinese (332,830 or 12.5%), and Black (239,850 or 8.9%).[20] Visible minorities are projected to increase to 63% of the city's population by 2031.[138]

This diversity is reflected in Toronto's ethnic neighbourhoods, which include Chinatown, Corso Italia, Greektown, Kensington Market (alternative/counterculture), Koreatown, Little India, Little Italy, Little Jamaica, Little Portugal and Roncesvalles (Polish community).[139]

Religion

In 2011, the most commonly reported religion in Toronto was Christianity, adhered to by 54.1% of the population. A plurality, 28.2%, of the city's population was Catholic, followed by Protestants (11.9%), Christian Orthodox (4.3%), and members of other Christian denominations (9.7%).

Other religions significantly practised in the city are Islam (8.2%), Hinduism (5.6%), Judaism (3.8%), Buddhism (2.7%), and Sikhism (0.8%). Those with no religious affiliation made up 24.2% of Toronto's population.[136]

Language

While English is the predominant language spoken by Torontonians, many other languages have considerable numbers of local speakers.[140] The varieties of Chinese and Italian are the second and third most widely spoken languages at work.[141][142] Despite Canada's official bilingualism, while 9.7% of Ontario's Francophones live in Toronto, only 0.6% of the population reported French as a singular language spoken most often at home; meanwhile 64% reported speaking predominantly English only and 28.3% primarily used a non-official language; 7.1% reported commonly speaking multiple languages at home.[143][144] The city's 9-1-1 emergency services are equipped to respond in over 150 languages.[145]

Government

Toronto is a single-tier municipality governed by a mayor–council system. The structure of the municipal government is stipulated by the City of Toronto Act. The Mayor of Toronto is elected by direct popular vote to serve as the chief executive of the city. The Toronto City Council is a unicameral legislative body, comprising 44 councillors representing geographical wards throughout the city.[146] The mayor and members of the city council serve four-year terms without term limits. (Until the 2006 municipal election, the mayor and city councillors served three-year terms.) However, on November 18, 2013, council voted to modify the city's government by transferring many executive powers from the mayor to the deputy mayor, and itself.[147]

As of 2016, the city council has twelve standing committees, each consisting of a chairman, (some have a vice-chair), and a number of councillors.[148] The Mayor names the committee chairs and the remaining membership of the committees is appointed by City Council. An executive committee is formed by the chairs of each of standing committee, along with the mayor, the deputy mayor and four other councillors. Councillors are also appointed to oversee the Toronto Transit Commission and the Toronto Police Services Board.

The city has four community councils that consider local matters. City Council has delegated final decision-making authority on local, routine matters, while others—like planning and zoning issues—are recommended to the city council. Each city councillor serves as a member of a community council.[148]

There are about 40 subcommittees and advisory committees appointed by the city council. These bodies are made up of city councillors and private citizen volunteers. Examples include the Pedestrian Committee, Waste Diversion Task Force 2010, and the Task Force to Bring Back the Don.[149]

The City of Toronto had an approved operating budget of CA$10.5 billion in 2017 and a 10-year capital budget and plan of CA$26.5 billion.[150] The city's revenues include subsidies from the Government of Canada and the Government of Ontario, 33% from property tax, 6% from the land transfer tax and the rest from other tax revenues and user fees.[151] The City's largest operating expenditures are the Toronto Transit Commission at CA$1.955 billion (19%), and the Toronto Police Service, CA$1.131 billion (9%).[151]

Crime

The low crime rate in Toronto has resulted in the city having a reputation as one of the safest major cities in North America.[152][153][154] For instance, in 2007, the homicide rate for Toronto was 3.3 per 100,000 people, compared with Atlanta (19.7), Boston (10.3), Los Angeles (10.0), New York City (6.3), Vancouver (3.1), and Montreal (2.6). Toronto's robbery rate also ranks low, with 207.1 robberies per 100,000 people, compared with Los Angeles (348.5), Vancouver (266.2), New York City (265.9), and Montreal (235.3).[155][156][157][158][159][160] Toronto has a comparable rate of car theft to various U.S. cities, although it is not among the highest in Canada.[152]

Toronto recorded its largest number of homicides in 1991 with 89, a rate of 3.9 per 100,000.[161][162] In 2005, Toronto media coined the term "Year of the Gun", because of a record number of gun-related homicides, 52, out of 80 homicides in total.[154][163] The total number of homicides dropped to 70 in 2006; that year, nearly 2,000 people in Toronto were victims of a violent gun-related crime, about one-quarter of the national total.[164] 84 homicides were committed in 2007, roughly half of which involved guns. Gang-related incidents have also been on the rise; between the years of 1997 and 2005, over 300 gang-related homicides have occurred. As a result, the Ontario government developed an anti-gun strategy.[165] In 2011, Toronto's murder rate plummeted to 45 murders—nearly a 26% drop from the previous year. The 45 homicides were the lowest number the city has recorded since 1986.[166] While subsequent years did see a return to higher rates, the nearly flat line of 56 homicides in 2012 and 57 in both 2013 and 2014 continued to be a significant improvement over the previous decade; and the year of 2015 had 55 murders by year end. 2016 went to 73 for the first time in over 8 years. 2017 had a drop off of 12 murders to close the year at 61.[167]

Education

Toronto has a number of post-secondary academic institutions. The University of Toronto, established in 1827, is Canada's largest university and has two satellite campuses, one of which is located in the city's eastern district of Scarborough while the other is located in the neighbouring city of Mississauga. York University, Canada's third-largest university, founded in 1959, is located in the northwest part of the city. Toronto is also home to Ryerson University, OCAD University, and the University of Guelph-Humber.

There are four diploma- and degree-granting colleges in Toronto. These are Seneca College, Humber College, Centennial College and George Brown College. The city is also home to a satellite campus of the francophone Collège Boréal.

The Royal Conservatory of Music, which includes the Glenn Gould School, is a school of music located downtown. The Canadian Film Centre is a film, television and new media training institute founded by filmmaker Norman Jewison. Tyndale University College and Seminary is a Christian post-secondary institution and Canada's largest seminary.

The Toronto District School Board (TDSB) operates 588 public schools. Of these, 451 are elementary and 116 are secondary (high) schools.[168] Additionally, the Toronto Catholic District School Board manages the city's publicly funded Roman Catholic schools, while the Conseil scolaire Viamonde and the Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir manage public and Roman Catholic French-language schools, respectively. There are also numerous private university-preparatory schools including the University of Toronto Schools, the Upper Canada College and Havergal College.

The Toronto Public Library[169] consists of 100[170] branches with more than 11 million items in its collection.[171]

Infrastructure

Health and medicine

Toronto is home to 20 public hospitals, including: The Hospital for Sick Children, Mount Sinai Hospital, St. Michael's Hospital, North York General Hospital, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, St. Joseph's Health Centre, Scarborough General Hospital, Scarborough Grace Hospital, Centenary Hospital, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), and Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, many of which are affiliated with the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine.

In 2007, Toronto was reported as having some of the longer average ER wait times in Ontario. Toronto hospitals at the time employed a system of triage to ensure life-threatening injuries receive rapid treatment.[172] After initial screening, initial assessments by physicians were completed within the waiting rooms themselves for greater efficiency, within a median of 1.2 hours. Tests, consultations, and initial treatments were also provided within waiting rooms. 50% of patients waited 4 hours before being transferred from the emergency room to another room.[172] The least-urgent 10% of cases wait over 12 hours.[172] The extended waiting-room times experienced by some patients were attributed to an overall shortage of acute care beds.[172]

Toronto's Discovery District[173] is a centre of research in biomedicine. It is located on a 2.5-square-kilometre (620-acre) research park that is integrated into Toronto's downtown core. It is also home to the Medical and Related Sciences Centre (MaRS),[174] which was created in 2000 to capitalize on the research and innovation strength of the Province of Ontario. Another institute is the McLaughlin Centre for Molecular Medicine (MCMM).[175]

Toronto also has some specialized hospitals located outside of the downtown core. These hospitals include Baycrest for geriatric care and Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital for children with disabilities.

Toronto is also host to a wide variety of health-focused non-profit organizations that work to address specific illnesses for Toronto, Ontario and Canadian residents. Organizations include Crohn's and Colitis Canada, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Cancer Society, the Alzheimer Society of Canada, Alzheimer Society of Ontario and Alzheimer Society of Toronto, all situated in the same office at Yonge and Eglinton, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of Canada, the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation, the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research, Cystic Fibrosis Canada, the Canadian Mental Health Association, the ALS Society of Canada, and many others. These organizations work to help people within the GTA, Ontario or Canada who are affected by these illnesses. As well, most engage in fundraising to promote research, services, and public awareness.

Transportation

.jpg)

Toronto is a central transportation hub for road, rail and air networks in Southern Ontario. There are many forms of transport in the city of Toronto, including highways and public transit. Toronto also has an extensive network of bicycle lanes and multi-use trails and paths.

Public transportation

Toronto's main public transportation system is operated by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC).[56] The backbone of its public transport network is the Toronto subway system, which includes three heavy-rail rapid transit lines spanning the city, including the U-shaped Line 1 and east-west Line 2. A light metro line also exists, exclusively serving the eastern district of Scarborough, but a discussion is underway to replace it with a heavy-rail line.

_(14918534190).jpg)

The TTC also operates an extensive network of buses and streetcars, with the latter serving the downtown core, and buses providing service to many parts of the city not served by the sparse subway network. TTC buses and streetcars use the same fare system as the subway, and many subway stations offer a fare-paid area for transfers between rail and surface vehicles.

There have been numerous plans to extend the subway and implement light-rail lines, but many efforts have been thwarted by budgetary concerns. Since July 2011, the only subway-related work is the Spadina subway (line 1) extension north of Sheppard West station (formerly named Downsview) to Vaughan Metropolitan Centre. By November 2011, construction on Line 5 Eglinton began. Line 5 is scheduled to finish by 2021.[176][177] In 2015, the Ontario government promised to fund Line 6 Finch West (line 7) which is to be completed by 2021.[178]

Toronto's public transit network also connects to other municipal networks such as York Region Transit, Viva, Durham Region Transit, and MiWay.

The Government of Ontario also operates a commuter rail and bus transit system called GO Transit in the Greater Toronto Area. GO Transit carries over 250,000 passengers every weekday (2013) and 57 million annually, with a majority of them travelling to or from Union Station.[179][180] GO Transit is implementing RER (Regional Express Rail) into its system.[181]

Airports

Canada's busiest airport, Toronto Pearson International Airport (IATA: YYZ), straddles the city's western boundary with the suburban city of Mississauga. Limited commercial and passenger service to nearby destinations in Canada and the USA is also offered from the Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport (IATA: YTZ) on the Toronto Islands, southwest of downtown. Buttonville Municipal Airport (IATA: YKZ) in Markham provides general aviation facilities. Downsview Airport (IATA: YZD), near the city's north end, is owned by de Havilland Canada and serves the Bombardier Aerospace aircraft factory.

The Union Pearson Express is a train service that provides a direct link between Pearson International and Union Station. It began carrying passengers in June 2015.

Hamilton's John C. Munro International Airport (IATA: YHM) and Buffalo's Buffalo Niagara International Airport (IATA: BUF) also serve as alternate airports for the Toronto area in addition to serving their respective cities.

Intercity transportation

Toronto Union Station serves as the hub for VIA Rail's intercity services in Central Canada, and includes services to various parts of Ontario, Corridor services to Montreal and national capital Ottawa, and long distance services to Vancouver and New York City.

The Toronto Coach Terminal in downtown Toronto also serves as a hub for intercity bus services in Southern Ontario, served by multiple companies and providing a comprehensive network of services in Ontario and neighboring provinces and states. GO Transit provides intercity bus services from Union Station Bus Terminal and other bus terminals in the city to destinations within the GTA.

Road system

The grid of major city streets was laid out by a concession road system, in which major arterial roads are 6,600 ft (2.0 km) apart (with some exceptions, particularly in Scarborough and Etobicoke, as they were originally separate townships). Major east-west arterial roads are generally parallel with the Lake Ontario shoreline, and major north-south arterial roads are roughly perpendicular to the shoreline, though slightly angled north of Eglinton Avenue. This arrangement is sometimes broken by geographical accidents, most notably the Don River ravines.

Toronto's grid north is approximately 18.5° to the west of true north.

There are a number of municipal expressways and provincial highways that serve Toronto and the Greater Toronto Area. In particular, Highway 401 bisects the city from west to east, bypassing the downtown core. It is the busiest road in North America,[182] and one of the busiest highways in the world.[183][184] Other provincial highways include Highway 400 which connects the city with Northern Ontario and beyond and Highway 404, an extension of the Don Valley Parkway into the northern suburbs. The Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW), North America's first divided intercity highway, terminates at Toronto's western boundary and connects Toronto to Niagara Falls and Buffalo. The main municipal expressways in Toronto include the Gardiner Expressway, the Don Valley Parkway, and to some extent, Allen Road. Toronto's traffic congestion is one of the highest in North America, and is the second highest in Canada after Vancouver, British Columbia.[185]

Notable people

Sister cities

Partnership cities

Friendship cities

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Benson, Denise. "Putting T-Dot on the Map". Eye Weekly. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- ↑ "Why is Toronto called 'Hogtown?'". funtrivia.com.

- ↑ "City nicknames". got.net.

- ↑ Johnson, Jessica (August 4, 2007). "Quirky finds in the Big Smoke". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008.

- ↑ "The real story of how Toronto got its name | Earth Sciences". Geonames.nrcan.gc.ca. September 18, 2007. Archived from the original on December 9, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- 1 2 "(Code 3520005) Census Profile". 2016 census. Statistics Canada. 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- 1 2 "Population and dwelling counts, for population centres, 2011 and 2006 censuses". 2011 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. January 13, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- 1 2 "Population and dwelling counts, for census metropolitan areas, 2011 and 2006 censuses". 2011 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. January 13, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- 1 2 "Global city GDP 2014". brookings.edu. Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ Robert Vipond (April 24, 2017). Making a Global City: How One Toronto School Embraced Diversity. University of Toronto Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4426-2443-6.

- ↑ David P. Varady (February 2012). Desegregating the City: Ghettos, Enclaves, and Inequality. SUNY Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7914-8328-2.

- ↑ Ute Husken; Frank Neubert (November 7, 2011). Negotiating Rites. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-19-981230-1.

- ↑ "First Peoples, 9000 BCE to 1600 CE – The History of Toronto: An 11,000-Year Journey – Virtual Exhibits | City of Toronto". toronto.ca. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Johnson & Wilson 1989, p. 34.

- ↑ "The early history of York & Upper Canada". Dalzielbarn.com. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ "The Battle of York, 200 years ago, shaped Toronto and Canada: Editorial". thestar.com. April 21, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Timeline: 180 years of Toronto history". Toronto.

- ↑ Citizenship and Immigration Canada (September 2006). "Canada-Ontario-Toronto Memorandum of Understanding on Immigration and Settlement (electronic version)". Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ↑ Flew, Janine; Humphries, Lynn; Press, Limelight; McPhee, Margaret (2004). The Children's Visual World Atlas. Sydney, Australia: Fog City Press. p. 76. ISBN 1-74089-317-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census: Toronto, City (CSD) – Ontario: Immigration and Ethnocultural diversity". Statistics Canada. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ↑ "Diversity – Toronto Facts – Your City. City of Toronto". Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Social Development, Finance & Administration" (PDF). toronto.ca. City of Toronto. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Music – Key Industry Sectors – City of Toronto". Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Quality of Life – Arts and Culture". Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Film & Television – Key Industry Sectors – City of Toronto". Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Made here. Seen everywhere. – Film in Toronto – City of Toronto". Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Ontario's Enertainment and Creative Cluster" (PDF). Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Culture, The Creative City". Toronto Press Room. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Cultural Institutions in the Public Realm" (PDF). Eraarch.ca. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Arts and Culture – Living in Toronto". toronto.ca. City of Toronto. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Tourism". toronto.ca. City of Toronto. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015.

- ↑ Melanson, Trevor. "What Toronto's skyline will look like in 2020". Canadian Business.

- ↑ Torontoist. "The CN Tower is Dead. Long Live The CN Tower!". torontoist.com.

- ↑ Duffy 2004, p. 154.

- ↑ Dinnie 2011, p. 21.

- 1 2 City of Toronto (2007) – Toronto economic overview, Key industry clusters. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ↑ ICF Consulting (February 2000). "Toronto Competes". toronto.ca. Archived from the original on January 27, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Business Toronto – Key Business Sectors". Investtoronto.ca. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Myrvold & Fahey 1997, pp. 12–18.