Toronto Maple Leafs

| Toronto Maple Leafs | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| |

| Conference | Eastern |

| Division | Atlantic |

| Founded | 1917 |

| History |

Toronto Arenas 1917–1919 Toronto St. Patricks 1919–1927 Toronto Maple Leafs 1927–present |

| Home arena | Scotiabank Arena |

| City | Toronto, Ontario |

|

| |

| Colours | |

| Media |

Leafs Nation Network Sportsnet Ontario TSN4 Sportsnet 590 The Fan TSN Radio 1050 |

| Owner(s) |

Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment Ltd. (Larry Tanenbaum, chairman) |

| General manager | Kyle Dubas |

| Head coach | Mike Babcock |

| Captain | Vacant |

| Minor league affiliates |

Toronto Marlies (AHL) Newfoundland Growlers (ECHL) |

| Stanley Cups | 13 (1917–18, 1921–22, 1931–32, 1941–42, 1944–45, 1946–47, 1947–48, 1948–49, 1950–51, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64, 1966–67) |

| Conference championships | 0 |

| Presidents' Trophy | 0[note 1] |

| Division championships | 5 (1932–33, 1933–34, 1934–35, 1937–38, 1999–2000) |

| Official website |

www |

The Toronto Maple Leafs (officially the Toronto Maple Leaf Hockey Club and often simply referred to as the Leafs) are a professional ice hockey team based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. They are members of the Atlantic Division of the Eastern Conference of the National Hockey League (NHL). The club is owned by Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment, Ltd. and are represented by Chairman Larry Tanenbaum. With an estimated value of US $1.4 billion in 2017 according to Forbes, the Maple Leafs are the second most valuable franchise in the NHL, after the New York Rangers.[3] The Maple Leafs' broadcasting rights are split between BCE Inc. and Rogers Communications.[4] For their first 14 seasons, the club played their home games at the Mutual Street Arena, before moving to Maple Leaf Gardens in 1931. The Maple Leafs moved to their present home, Scotiabank Arena (originally named the Air Canada Centre) in February 1999.

The club was founded in 1917, operating simply as Toronto and known then as the Toronto Arenas. Under new ownership, the club was renamed the Toronto St. Patricks in 1919. In 1927 the club was purchased by Conn Smythe and renamed the Maple Leafs. A member of the "Original Six", the club was one of six NHL teams to have endured through the period of League retrenchment during the Great Depression. The club has won thirteen Stanley Cup championships, second only to the 24 championships of the Montreal Canadiens. The Maple Leafs history includes two recognized dynasties, from 1947 to 1951; and from 1962 to 1967.[5][6] Winning their last championship in 1967, the Maple Leafs' 50-season drought between championships is the longest current drought in the NHL. The Maple Leafs have developed rivalries with three NHL franchises, the Detroit Red Wings, the Montreal Canadiens, and the Ottawa Senators.

The Maple Leafs have retired the use of thirteen numbers in honour of nineteen players. In addition, a number of individuals who hold an association with the club have been inducted in the Hockey Hall of Fame. The Maple Leafs are presently affiliated with two minor league teams, the Toronto Marlies of the American Hockey League, and the Newfoundland Growlers of the ECHL.

Team history

Early years (1917–1927)

The National Hockey League was formed in 1917 in Montreal by teams formerly belonging to the National Hockey Association (NHA) that had a dispute with Eddie Livingstone, owner of the Toronto Blueshirts. The owners of the other four clubs — the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Quebec Bulldogs and the Ottawa Senators — wanted to replace Livingstone, but discovered that the NHA constitution did not allow them to simply vote him out of the league.[7] Instead, they opted to create a new league, the NHL, and did not invite Livingstone to join them. They also remained voting members of the NHA, and thus had enough votes to suspend the other league's operations, effectively leaving Livingstone's league with one team.[8]

| Part of the series on | ||||||||||

| Evolution of the Toronto Maple Leafs | ||||||||||

| Teams | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Ice hockey portal · |

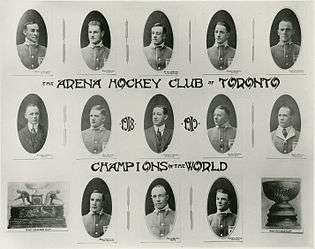

The NHL had decided that it would operate a four-team circuit, made up of the Canadiens, Maroons, Ottawa, and one more club in either Quebec or Toronto. Toronto's inclusion in the NHL's inaugural season was formally announced on November 26, 1917, with concerns over the Bulldog's financial stability surfacing.[9] The League granted temporary franchise rights to the Arena Company, owners of the Arena Gardens.[10] The NHL granted the Arena responsibility of the Toronto franchise for only the inaugural season, with specific instructions to resolve the dispute with Livingstone, or transfer ownership of the Toronto franchise back to the League at the end of the season.[11] The franchise did not have an official name, but was informally called "the Blueshirts" or "the Torontos" by the fans and press.[12] Although the inaugural roster was made up of players leased from the NHA's Toronto Blueshirts, including Harry Cameron and Reg Noble, the Blueshirts are viewed as a separate franchise.[13] During the inaugural season the club performed the first trade in NHL history, sending Sammy Hebert to the Senators, in return for cash.[14] Under manager Charlie Querrie, and head coach Dick Carroll, the team won the Stanley Cup in the inaugural 1917–18 season.[15]

For the next season, rather than return the Blueshirts' players to Livingstone as originally promised, on October 19, 1918, the Arena Company applied to become permanent franchise, the Toronto Arena Hockey Club, which was readily granted by the NHL.[16] The Arena Company also decided that year that only NHL teams were allowed to play at the Arena Gardens—a move which effectively killed the NHA.[17] Livingstone sued to get his players back. Mounting legal bills from the dispute forced the Arenas to sell some of their stars, resulting in a horrendous five-win season in 1918–19. With the company facing increasing financial difficulties, and the Arenas officially eliminated from the playoffs, the NHL agreed to let the team forfeit their last two games.[14][18] Operations halted on February 20, 1919, with the NHL ending its season and starting the playoffs. The Arenas' .278 winning percentage that season remains the worst in franchise history. However, the 1919 Stanley Cup Finals ended without a winner due to the worldwide flu epidemic.[14]

The legal dispute forced the Arena Company into bankruptcy, and it was forced to sell the team. On December 9, 1919, Querrie brokered the team's purchase by the owners of the St. Patricks Hockey Club, allowing him to maintain an ownership stake in the team.[19] The new owners renamed the team the Toronto St. Patricks (or St. Pats for short), which they used until 1927.[20] Changing the colours of the team from blue to green, the club won their second Stanley Cup championship in 1922.[18] Babe Dye scored four times in the 5–1 Stanley Cup-clinching victory against the Vancouver Millionaires.[21] In 1924 Jack Bickell invested C$25,000 in the St. Pats as a favour to his friend Querrie, who needed to financially reorganize his hockey team.[22]

Conn Smythe era (1927–1961)

After a number of financially difficult seasons, the St. Patricks' ownership group seriously considered selling the team to C. C. Pyle for C$200,000 (equivalent to $2,866,000 in 2017). Pyle sought to move the team to Philadelphia.[18][23] However, Toronto Varsity Blues coach Conn Smythe put together a group of his own and made a $160,000 (equivalent to $2,293,000 in 2017) offer. With the support of St. Pats shareholder J. P. Bickell, Smythe persuaded Querrie to accept their bid, arguing that civic pride was more important than money.[23]

After taking control on February 14, 1927, Smythe immediately renamed the team the Maple Leafs, after the national symbol of Canada.[24] He attributed his choice of a maple leaf for the logo to his experiences as a Canadian Army officer and prisoner of war during World War I. Viewing the maple leaf as a "badge of courage", and a reminder of home, Smythe decided to give the same name to his hockey team, in honour of the many Canadian soldiers who wore it.[18][25][26] However, the team was not the first to use the name. A Toronto minor-league baseball team had used the name "Maple Leafs" since 1895.[27]

Initial reports were that the team's colours were to be red and white,[28] but the Leafs wore white sweaters with a green maple leaf for their first game on February 17, 1927.[29] On September 27, 1927, it was announced that the Leafs had changed their colour scheme to blue and white.[30] Although Smythe later stated he chose blue because it represents the Canadian skies and white to represent snow, these colours were also used on his gravel and sand business' trucks.[30] The colour blue was also a colour historically associated with the City of Toronto. The use of blue by Toronto-based sports clubs began with the Argonaut Rowing Club in the 19th century, later adopted by their football team, the Toronto Argonauts, in 1873.[31]

Opening of Maple Leaf Gardens (1930s)

By 1930 Smythe saw the need to construct a new arena, viewing the Arena Gardens as a facility lacking modern amenities and seating.[32] Finding an adequate number of financiers, he purchased land from the Eaton family, and construction of the arena was completed in five months.[33][34]

The Maple Leafs debuted at their new arena, Maple Leaf Gardens, with a 2–1 loss to the Chicago Black Hawks on November 12, 1931.[34] The opening ceremonies for Maple Leaf Gardens included a performance from the 48th Highlanders of Canada Pipe and Drums.[35] The military band has continued to perform in every subsequent season home opening game, as well as other ceremonies conducted by the hockey club.[36][37] The debut also featured Foster Hewitt in his newly constructed press box above the ice surface, where he began his famous Hockey Night in Canada radio broadcasts that eventually came to be a Saturday-night tradition.[34] The press box was often called 'the gondola', a name that emerged during the Gardens' inaugural season, when a General Motors advertising executive remarked how it resembled the gondola of an airship.[38]

By the 1931–32 NHL season, the Maple Leafs were led by the "Kid Line" consisting of Busher Jackson, Joe Primeau and Charlie Conacher and coached by Dick Irvin. The team captured their third Stanley Cup that season, vanquishing the Chicago Black Hawks in the first round, the Montreal Maroons in the semifinals, and the New York Rangers in the finals.[39] Smythe took particular pleasure in defeating the Rangers that year. He had been tapped as the Rangers' first general manager and coach for their inaugural season (1926–27), but had been fired in a dispute with Madison Square Garden management before the season had begun.[40]

Maple Leafs' star forward Ace Bailey was nearly killed in 1933 when Boston Bruins defenceman Eddie Shore checked him from behind at full speed into the boards.[41] Leafs defenceman Red Horner knocked Shore out with a punch, but Bailey, writhing on the ice, had his career ended.[34] The Leafs held the Ace Bailey Benefit Game, the NHL's first All-Star Game, to collect medical funds to help Bailey. His jersey was retired later the same night.[42] The Leafs reached the finals five times in the next seven years, but bowed out to the now-defunct Maroons in 1935, the Detroit Red Wings in 1936, Chicago in 1938, Boston in 1939 and the Rangers in 1940.[34] After the end of the 1939–40 season, Smythe allowed Irvin to leave the team as head coach, replacing him with former Leafs captain Hap Day.[34]

The first dynasty (1940s)

In the 1942 Stanley Cup Finals, the Maple Leafs were down three games to none in the best-of-seven series against Detroit. Fourth-line forward Don Metz then galvanized the team, to score a hat-trick in game four and the game-winner in game five.[43] Goalie Turk Broda shut out the Wings in game six, and Sweeney Schriner scored two goals in the third period to win the seventh game 3–1, completing the reverse-sweep.[44] The Leafs remain the only team to have successfully performed a reverse-sweep in the Stanley Cup finals.[45] Captain Syl Apps won the Lady Byng Memorial Trophy that season, not taking one penalty, and finished his ten-season career with an average of 5 minutes, 36 seconds in penalties a season.[46]

Smythe, who reenlisted in the Canadian Army at the outbreak of World War II, was given leave from military duty to view the final game of the 1942 finals. He arrived at the game in full military regalia.[44] Earlier, at the outbreak of war, Smythe arranged for many of his Maple Leafs players and staff to take army training with the Toronto Scottish Regiment. Most notably, the Leafs announced a large portion of their roster had enlisted, including Apps, and Broda,[47] who did not play on the team for several seasons due to their obligations with the Canadian Forces.[48] During this period, the Leafs turned to lesser-known players such as rookie goaltender Frank McCool and defenceman Babe Pratt.[48][49]

The Maple Leafs beat the Red Wings in the 1945 Finals. They won the first three games, with goaltender McCool recording consecutive shutouts. However, in a reverse of the 1942 finals, the Red Wings won the next three games.[48] The Leafs were able to win the series, winning the seventh game by the score of 2–1 to prevent a complete reversal of the series played three years ago.[48]

After the end of the war, players who had enlisted were beginning to return to their teams.[48] With Apps and Broda regaining their form, the Maple Leafs beat the first-place Canadiens in the 1947 finals.[48] In an effort to bolster their centre depth, the Leafs acquired Cy Thomas and Max Bentley in the following the off-season. With these key additions, the Leafs were able to win a second consecutive Stanley Cup, sweeping the Red Wings in the 1948 finals.[48] With their victory in 1948, the Leafs moved ahead of Montreal as the team having won the most Stanley Cups in League history. Apps announced his retirement following the 1948 finals, with Ted Kennedy replacing him as the team's captain.[50] Under a new captaincy, the Leafs managed to make it to the 1949 finals, facing the Red Wings, who had finished the season with the best overall record. However, the Leafs went on to win their third consecutive Cup, sweeping the Red Wings in four games. This brought the total of Detroit's play off game losses against the Leafs to eleven.[48] The Red Wings were able to end this losing streak in the following post-season, eliminating Toronto in the 1950 NHL playoffs.[48]

The Barilko Curse (1950s)

The Maple Leafs and Canadiens met again in the 1951 finals, with five consecutive overtime games played in the series.[51] Defenceman Bill Barilko managed to score the series-winning goal in overtime, leaving his defensive position (in spite of coach Joe Primeau's instructions not to) to pick up an errant pass and score.[51] Barilko helped the club secure its fourth Stanley Cup in five years. His glory was short-lived, as he disappeared in a plane crash near Timmins, Ontario, four months later.[51][52] The crash site was not found until a helicopter pilot discovered the plane's wreckage plane about 80 kilometres (50 mi) north of Cochrane, Ontario eleven years later.[53] The Leafs did not win another Cup during the 1950s, with rumours swirling that the team was "cursed", and would not win a cup until Barilko's body was found.[54] The "curse" came to an end after the Leafs' 1962 Stanley Cup victory, which came six weeks before to the discovery of the wreckage of Barilko's plane.[54]

Their 1951 victory was followed by lacklustre performances in the following seasons. The team finished third in the 1951–52 season, and were eventually swept by the Red Wings in the semi-finals.[51] With the conclusion of the 1952–53 regular season, the Leafs failed to make it to the post-season for the first time since the 1945–46 playoffs.[51] The Leafs' poor performance may be attributed partly to a decline in their sponsored junior system (including the Toronto St. Michael's Majors and the Toronto Marlboros).[51] The junior system was managed by Frank J. Selke until his departure to the Canadiens in 1946. In his absence, the quality of players it produced declined. Many who were called up to the Leafs in the early 1950s were found to be seriously lacking in ability. It was only later in the decade that the Leafs' feeder clubs produced prospects that helped them become competitive again.[51]

After a two-year drought from the playoffs, the Maple Leafs clinched a berth after the 1958–59 season. Under Punch Imlach, their new general manager and coach, the Leafs made it to the 1959 Finals, losing to the Canadiens in five games.[51] Building on a successful playoff run, the Leafs followed up with a second-place finish in the 1959–60 regular season. Although they advanced to their second straight Cup Finals, the Leafs were again defeated by the Canadiens in four games.[51]

New owners and a new dynasty (1961–1971)

Beginning in the 1960s, the Leafs became a stronger team, with Johnny Bower as goaltender, and Bob Baun, Carl Brewer, Tim Horton and Allan Stanley serving as the Maple Leafs' defencemen.[55] In an effort to bolster their forward group during the 1960 off-season, Imlach traded Marc Reaume to the Red Wings for Red Kelly. Originally a defenceman, Kelly was asked to make the transition to the role of centre, where he remained for the rest of his career.[55] Kelly helped reinforce a forward group made up of Frank Mahovlich, and team captain George Armstrong. The beginning of the 1960–61 season also saw the debut of rookies Bob Nevin, and Dave Keon. Keon previously played for the St. Michael's Majors (the Maple Leafs junior affiliate), but had impressed Imlach during the Leafs' training camp, and joined the team for the season.[55] Despite these new additions, the Leafs' 1961 playoff run ended in the semifinals against the Red Wings, with Armstrong, Bower, Kelly and others, suffering from injuries.[55]

In November 1961, Smythe sold nearly all of his shares in the club's parent company, Maple Leaf Gardens Limited (MLGL), to a partnership composed of his son Stafford Smythe, and his partners, newspaper baron John Bassett and Toronto Marlboros President Harold Ballard. The sale price was $2.3 million (equivalent to $19,103,000 in 2017), a handsome return on Smythe's original investment 34 years earlier.[56] Initially, Conn Smythe claimed that he knew nothing about his son's partners and was furious with the arrangement. However, he did not stop the deal because of it.[57] Conn Smythe was given a retiring salary of $15,000 per year for life, an office, secretary, a car with a driver, and seats to home games.[58] Smythe sold his remaining shares in the company, and resigned from the board of directors in March 1966, after a Muhammad Ali boxing match was scheduled for the Gardens. Smythe found Ali's refusal to serve in the United States Army offensive, noting that the Gardens was "no place for those who want to evade conscription in their own country".[59] He had also said that because the Gardens' owners agreed to host the fight they had "put cash ahead of class".[60]

Under the new ownership, Toronto won another three straight Stanley Cups. The team won the 1962 Stanley Cup Finals beating the defending champion Chicago Black Hawks on a goal from Dick Duff in Game 6.[61] During the 1962–63 season, the Leafs finished first in the league for the first time since the 1947–48 season. In the following playoffs, the team won their second Stanley Cup of the decade.[55] The 1963–64 season saw certain members of the team traded. With Imlach seeking to reinvigorate the slumping Leafs, he made a mid-season trade that sent Duff, and Nevin to the Rangers for Andy Bathgate and Don McKenney. The Leafs managed to make the post-season as well as the Cup finals. In game six of the 1964 Cup finals, Baun suffered a fractured ankle and required a stretcher to be taken off the ice. He returned to play with his ankle frozen, and eventually scored the game-winning goal in overtime against the Red Wings.[62][55] The Leafs won their third consecutive Stanley Cup in a 4-0 game 7 victory; Bathgate scored two goals.[55]

The two seasons after the Maple Leafs' Stanley Cup victories, the team saw several player departures, including Bathgate, and Brewer, as well as several new additions, including Marcel Pronovost, and Terry Sawchuk.[55] During the 1966–67, the team had lost 10 games in a row, sending Imlach to the hospital with a stress-related illness. However, from the time King Clancy took over as the head coach, to Imlach's return, the club was on a 10-game undefeated streak, building momentum before the playoffs.[55] The Leafs made their last Cup finals in 1967. Playing against Montreal, the heavy favourite for the year, the Leafs managed to win, with Bob Pulford scoring the double-overtime winner in game three; Jim Pappin scored the series winner in Game 6.[63] Keon was named the playoff's most valuable player, and was awarded the Conn Smythe Trophy.[64]

From 1968 to 1970, the Maple Leafs made it to the playoffs only once. They lost several players to the 1967 expansion drafts, and the team was racked with dissension because of Imlach’s authoritative manner, and his attempts to prevent the players from joining the newly formed Players' Association.[55] Imlach's management of the team was also brought into question due to some of his decisions. It was apparent that he was too loyal to aging players who had been with him since 1958.[55] In 1967–68 season, Mahovlich was traded to Detroit in a deal that saw the Leafs acquire Paul Henderson, and Norm Ullman.[65] The Leafs managed to return to the playoffs after the 1968–69 season, only to be swept by the Bruins. Immediately after, Stafford Smythe confronted Imlach and fired him.[66] This act was not without controversy, with some older players, including Horton, declaring that, "if this team doesn't want Imlach, I guess it doesn't want me".[67]

The Maple Leafs completed the 1969–70 season out of the playoffs. With their low finish, the Leafs were able to draft Darryl Sittler at the 1970 NHL Amateur Draft.[68] The Leafs returned to the playoffs after the 1970–71 season with the addition of Sittler, as well as Bernie Parent and Jacques Plante, who were both acquired through trades during the season.[69] They were eliminated in the first round against the Rangers.[70]

The Ballard years (1971–1990)

A series of events in 1971 made Harold Ballard the primary owner of the Maple Leafs. After a series of disputes between Bassett, Ballard and Stafford Smythe, Bassett sold his stake in the company to them.[71] Shortly afterwards, Smythe died in October 1971. Under the terms of Stafford's will, of which Ballard was an executor, each partner was allowed to buy the other's shares upon their death.[71] Stafford's brother and son tried to keep the shares in the family,[72] but in February 1972 Ballard bought all of Stafford's shares for $7.5 million, valuing the company at $22 million (equivalent to $130,995,000 in 2017).[73][74][75] Six months later, Ballard was convicted of charges including fraud, and theft of money and goods, and spent a year at Milhaven Penitentiary.[69][71]

By the end of 1971, the World Hockey Association (WHA) began operations as a direct competitor to the NHL. Believing the WHA would not be able to compete against the NHL, Ballard's attitude caused the Maple Leafs to lose key players, including Parent to the upstart league.[69] Undermanned and demoralized, the Leafs finished with the fourth-worst record for the 1972–73 season. They got the fourth overall pick in the 1973 NHL Amateur Draft,[69] and drafted Lanny McDonald. General Manager Jim Gregory also acquired the 10th overall pick from the Philadelphia Flyers, and the 15th overall pick from the Bruins, using them to acquire Bob Neely and Ian Turnbull.[69] In addition to these first round picks, the Leafs also acquired Börje Salming during the 1973 off-season.[76]

Despite acquiring Tiger Williams in the 1974 draft, and Roger Neilson as head coach in the 1977–78 season, the Maple Leafs found themselves eliminated in the playoffs by stronger Flyers or Canadiens teams from 1975 to 1979.[69] Although Neilson was a popular coach with fans and his players, he found himself at odds with Ballard, who fired him late in the 1977–78 season. Nielson was later reinstated after appeals from the players and public.[77] He continued as Leafs' head coach until after the 1979 playoffs, when he was fired again, alongside Gregory.[69] Gregory was replaced by Imlach as General Manager.[69]

In the first year of his second stint as general manager, Imlach became embroiled in a dispute with Leafs' captain Darryl Sittler over his attempt to take part in the Showdown series for Hockey Night in Canada.[69][78] In a move to undermine Sittler's influence on the team, Imlach traded McDonald, who was Sittler's friend.[79] By the end of the 1979–80 season, Imlach had traded away nearly half of the roster he had at the beginning of his tenure as general manager.[80] With the situation between Ballard and Sittler worsening, Sittler asked to be traded.[81] Forcing the Leafs' hand, the club's new general manager, Gerry McNamara, traded Sittler to the Flyers on January 20, 1982.[82] Rick Vaive was named the team's captain shortly after Sittler's departure.[80]

The Maple Leafs' management continued in disarray throughout most of the decade, with an inexperienced McNamara named as Imlach's replacement in September 1981.[80] He was followed by Gord Stellick on April 28, 1988, who was replaced by Floyd Smith on August 15, 1989.[80] Coaching was similarly shuffled often after Nielson's departure. Imlach’s first choice for coach was his former player Smith, although he did not finish the 1979–80 season after being hospitalized by a car accident on March 14, 1980.[83] Joe Crozier was named the new head coach until January 10, 1981, when he was succeeded by Mike Nykoluk. Nykoluk was head coach until April 2, 1984.[80] Dan Maloney returned as head coach from 1984 to 1986, with John Brophy named head coach from 1986 to 1988. Both coaches had little success during their tenures.[80][84] Doug Carpenter was named the new head coach to begin the 1989–90 season, when the Leafs posted their first season above .500 in the decade.[80]

The team did not have much success during the decade, missing the playoffs entirely in 1982, 1984 and 1985.[80] On at least two occasions, they made the playoffs with the worst winning percentages on record for a playoff team. However, in those days, the top four teams in each division made the playoffs, regardless of record. In 1985–86, for instance, they finished with a .356 winning percentage, fourth-worst in the league. However, due to playing in a Norris Division where no team cracked the 90-point mark, the Leafs still made the playoffs. In 1987-88, they finished with the second-worst record in the league, and only one point ahead of the Minnesota North Stars for the worst record. However, the Red Wings were the only team in the division with a winning record, meaning that the Leafs and Stars were both in playoff contention on the season's final day. The Leafs upset the Red Wings in their final game, while the Stars lost to the Flames hours later to hand the Leafs the final spot from the Norris.

However, the low finishes allowed the team to draft Wendel Clark first overall at the 1985 NHL Entry Draft.[80] Clark managed to lead the Leafs to the playoffs from 1986 to 1988, as well as the 1990 playoffs, although they were always eliminated in the first round.[80] Ballard died on April 11, 1990.[85]

Resurgence (1990–2004)

Don Crump, Don Giffin, and Steve Stavro were named executors of Ballard's estate.[86] Stavro succeeded Ballard as chairman of Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. and governor of the Maple Leafs.[87] Cliff Fletcher was hired by Giffin to be the new general manager, although this was opposed by Stavro, who told Fletcher that he wanted to appoint his own general manager.[88] In 1992, Fletcher set about building a competitive club, hiring Pat Burns as the new coach, and by making a series of trades and free agent acquisitions, such as acquiring Doug Gilmour and Dave Andreychuk, which turned the Leafs into a contender.[89] Assisted by stellar goaltending from minor league call-up Felix Potvin, the team posted a then-franchise-record 99 points.[90]

Toronto dispatched the Detroit Red Wings in seven games in the first round, then defeated the St. Louis Blues in another seven games in the Division Finals.[89] Hoping to meet long-time rival Montreal (who was playing in the Wales Conference finals against the New York Islanders) in the Cup finals, the Leafs faced the Los Angeles Kings in the Campbell Conference finals.[89] They led the series 3–2, but dropped game six in Los Angeles. The game was not without controversy, as Wayne Gretzky clipped Gilmour in the face with his stick, but referee Kerry Fraser did not call a penalty, and Gretzky scored the winning goal moments later.[91] The Leafs eventually lost in game seven 5–4.[89]

The Leafs had another strong season in 1993–94, starting the season on a 10-game winning streak, and finishing it with 98 points.[89] The team made it to the conference finals again, only to be eliminated by the Vancouver Canucks in five games.[89] At the 1994 NHL Entry Draft, the Leafs packaged Wendel Clark in a multi-player trade with the Quebec Nordiques that landed them Mats Sundin.[89] Missing two consecutive playoffs in 1997 and 1998, the Leafs relieved Fletcher as general manager.[89]

New home and a new millennium (1998–2004)

On February 12, 1998, MLGL purchased the Toronto Raptors, a National Basketball Association franchise, and the arena the Raptors were building, from Allan Slaight and Scotiabank.[92][93][94] With the acquisition, MLGL was renamed to Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment (MLSE), acting as the parent company of the two teams.[94] Larry Tanenbaum was a driving force in the acquisition, having bought a bought a 12.5 percent stake in Maple Leaf Gardens Limited (MLGL) in 1996.[95][96]

Curtis Joseph was acquired as the team's starting goalie, while Pat Quinn was hired as the head coach before the 1998–99 season.[89] Realigning the NHL's conferences in 1998, the Leafs were moved from the Western to the Eastern Conference.[93] On February 13, 1999, the Leafs played their final game at the Gardens before moving to their new home at the then-Air Canada Centre.[97] In the 1999 playoffs, the team advanced to the Conference Finals, but lost in five games to the Buffalo Sabres.[89]

In the 1999–2000 season, the Leafs hosted the 50th NHL All-Star Game.[98] By the end of the season, they recorded their first 100-point season and won their first division title in 37 years.[99] In both the 2000 and 2001 playoffs, the Leafs defeated the Ottawa Senators in the first round, and lost to the New Jersey Devils in the second round.[99][100] In 2002 playoffs, the Leafs dispatched the Islanders and the Senators, in the first two rounds, only to lose to the Cinderella-story Carolina Hurricanes in the Conference Finals.[101] The 2002 season was particularly impressive in that injuries sidelined many of the Leafs' better players, but the efforts of depth players, including Alyn McCauley, Gary Roberts and Darcy Tucker, led them to the Conference Finals.[102]

As Joseph opted to become a free agent during the 2002 off-season, the Leafs signed Ed Belfour as the new starting goaltender.[103] Belfour played well during the 2002–03 season and was a finalist for the Vezina Trophy.[104] The Leafs lost to Philadelphia in seven games during the first round of the 2003 playoffs.[105] In 2003, an ownership change occurred in MLSE. Stavro sold his controlling interest in MLSE to the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTPP) and resigned his position as chairman in favour of Tanenbaum.[106] Quinn remained as head coach, but was replaced as general manager by John Ferguson Jr..[107]

Before the 2003–04 season, the team held their training camp in Sweden and played in the NHL Challenge against teams from Sweden and Finland.[108] The Leafs went on to enjoy a very successful regular season, leading the NHL at the time of the All-Star Game (with Quinn named head coach of the East's All-Star Team). They finished the season with a then-franchise-record 103 points.[109] They finished with the fourth-best record in the League, and their highest overall finish in 41 years, achieving a .628 win percentage, their best in 43 years, and third-best in franchise history. In the 2004 playoffs, the Leafs defeated the Senators in the first round of the post-season for the fourth time in five years, with Belfour posting three shutouts in seven games, but lost to the Flyers in six games during the second round.[109]

After the lockout (2005–2014)

Following the 2004–05 NHL lockout, the Maple Leafs experienced their longest playoff drought in the club's history. They struggled in the 2005–06 season; despite a late-season surge (9–1–2 in their final 12 games), led by goaltender Jean-Sebastien Aubin, Toronto was out of playoff contention for the first time since 1998.[110] This marked the first time the team had missed the postseason under Quinn, who was later relieved as head coach.[111] Quinn's dismissal was controversial since many of the young players who were key contributors to the Leafs' late-season run had been drafted by him before Ferguson's arrival, while Ferguson's signings (Jason Allison, Belfour, Alexander Khavanov, and Eric Lindros) had suffered season-ending injuries.[111][112]

Paul Maurice, who had previously coached the inaugural season of the Maple Leafs' Toronto Marlies farm team, was named as Quinn's replacement.[113] On June 30, 2006, the Leafs bought out fan-favourite Tie Domi's contract. The team also decided against picking up the option year on goaltender Ed Belfour's contract; he became a free agent.[114] However, despite the coaching change, as well as a shuffle in the roster, the team did not make the playoffs in 2006–07. During the 2007–08 season, John Ferguson, Jr. was fired in January 2008, and replaced by former Leafs' general manager Cliff Fletcher on an interim basis.[115] The Leafs did not qualify for the post-season, marking the first time since 1928 the team had failed to make the playoffs for three consecutive seasons.[116] It was also Sundin's last year with the Leafs, as his contract was due to expire at the end of the season. However, he refused Leafs management's request to waive his no-trade clause in order for the team to rebuild by acquiring prospects and/or draft picks.[117] On May 7, 2008, after the 2007–08 season, the Leafs fired Maurice, as well as assistant coach Randy Ladouceur, naming Ron Wilson as the new head coach, and Tim Hunter and Rob Zettler as assistant coaches.[118]

On November 29, 2008, the Maple Leafs hired Brian Burke as their 13th non-interim, and the first American, general manager in team history. The acquisition ended the second Cliff Fletcher era and settled persistent rumours that Burke was coming to Toronto.[119] On June 26, 2009, Burke made his first appearance as the Leafs GM at the 2009 NHL Entry Draft, selecting London Knights forward Nazem Kadri with the seventh overall pick.[120] On September 18, 2009, Burke traded Toronto's first- and second-round 2010, as well as its 2011 first-round picks, to the Boston Bruins in exchange for forward Phil Kessel.[121] On January 31, 2010, the Leafs made another high-profile trade, this time with the Calgary Flames in a seven-player deal that brought defenceman Dion Phaneuf to Toronto.[122] On June 14, during the off-season, the Leafs named Phaneuf captain after two seasons without one following Sundin's departure.[123] On February 18, 2011, the team traded long-time Maple Leafs defenceman Tomas Kaberle to the Bruins in exchange for prospect Joe Colborne, Boston's first-round pick in 2011, and a conditional second-round draft choice.[124]

On March 2, 2012, Burke fired Wilson and named Randy Carlyle the new head coach. However, the termination proved to be controversial as Wilson had received a contract extension just two months prior to being let go.[125] Changes at the ownership level also occurred in August 2012, when the OTPP completed the sale of their shares in MLSE to BCE Inc. and Rogers Communications.[126] On January 9, 2013, Burke was fired as general manager, replaced by Dave Nonis.[127] In their first full season under the leadership of Carlyle, Toronto managed to secure a playoff berth in the 2012–13 season (which was shortened again due to another lock-out) for the first time in eight years. However, the Leafs lost in seven games to eventual 2013 Stanley Cup finalist Boston in the first round.[128] Despite the season's success, it was not repeated during the 2013–14 season, as the Leafs failed to make the playoffs.[129]

Brendan Shanahan era (2014–present)

Shortly after the end of the 2013–14 regular season, Brendan Shanahan was named as the president and an alternate governor of the Maple Leafs.[130] On January 6, 2015, the Leafs fired Randy Carlyle as head coach, and assistant coach Peter Horachek took over on an interim basis immediately.[131] While the Leafs had a winning record before Carlyle's firing, the team eventually collapsed. On February 6, 2015, the Leafs set a new franchise record of 11 consecutive games without a win. At the beginning of February, Shanahan gained the approval of MLSE's Board of Directors to begin a "scorched earth" rebuild of the club.[132] Both Dave Nonis and Horachek were relieved of their duties on April 12, just one day after the season concluded. In addition, the Leafs also fired a number of assistant coaches, including Steve Spott, Rick St. Croix; as well as individuals from the Leafs' player scouting department.[133][134]

On May 20, 2015, Mike Babcock was named as the new head coach, and on June 23, Lou Lamoriello was named the 16th general manager in team history.[135][136] On July 1, 2015, the Leafs packaged Kessel in a multi-player deal to the Pittsburgh Penguins in return for three skaters, including Kasperi Kapanen, a conditional first round pick, and a third round pick. Toronto also retained $1.2 million of Kessel's salary for the remaining seven seasons of his contract.[137] During the following season, on February 9, 2016, the Leafs packaged Phaneuf in another multi-player deal, acquiring four players, as well as a 2017 2nd-round pick from the Ottawa Senators.[138] The team finished last in the NHL for the first time since the 1984–85 season. They subsequently won the draft lottery and used the first overall pick to draft Auston Matthews.[139]

In their second season under Babcock, Toronto secured the final Eastern Conference wildcard spot for the 2017 playoffs. On April 23, 2017, the Maple Leafs were eliminated from the playoffs by the top-seeded Washington Capitals four games to two in the best-of-seven series.[140]

Toronto finished the 2017–18 season with 105 points by beating Montreal 4–2 in their final game of the regular season, a franchise-record, beating the previous record of 103 points set in 2004.[141] They faced the Boston Bruins in the First Round and lost in seven games.[142] Following the playoffs, Lamoriello was not renewed as general manager.[143] Kyle Dubas was subsequently named the team's 17th general manager in May 2018.[144]. During the 2018 off-season, the Maple Leafs signed John Tavares to a seven-year, $77-million dollar contract.[145] Tavares was subsequently named an alternate captain for the Leafs, alongside Morgan Rielly, and Patrick Marleau.[146]

Team culture

Fan base

The price of a Maple Leafs home game ticket is the highest amongst any team in the NHL.[147][148][149] The Scotiabank Arena holds 18,900 seats for Leafs games, with 15,500 reserved for season ticket holders.[150] Because of the demand for season tickets, their sale is limited to the 10,000 people on the waiting list. As of March 2016, Leafs' season tickets saw a renewal rate of 99.5 percent, a rate that would require more than 250 years to clear the existing waiting list.[150] In a 2014 survey by ESPN The Magazine, the Leafs were ranked last out of the 122 professional teams in the Big Four leagues. Teams were graded by stadium experience, ownership, player quality, ticket affordability, championships won and "bang for the buck"; in particular, the Leafs came last in ticket affordability.[151]

Leafs fans have been noted for their loyalty to the team, in spite of their performance.[152][153] In a study conducted by Fanatics in March 2017, the Leafs and the Minnesota Wild were the only two NHL teams to average arena sellouts, with average win percentages below the league's average.[154] Conversely, fans of other teams harbour an equally passionate dislike of the team. In November 2002, the Leafs were named by Sports Illustrated hockey writer Michael Farber as the "Most Hated Team in Hockey".[155]

Despite their loyalty, there have been several instances where the fanbase voiced their displeasure with the club. During the 2011–12 season, fans attending the games chanted for the dismissal of head coach Ron Wilson, and later general manager Brian Burke.[156][157] Wilson was let go shortly after the fans' outburst, even though he had been given a contract extension months earlier. Burke alluded to the chants noting "it would be cruel and unusual punishment to let Ron coach another game in the Air Canada Centre".[156] In the 2014–15 season fans threw Leafs jerseys onto the ice to show their disapproval of the team's poor performances in the past few decades.[158] Similarly, during the later portion of the 2015–16 season, which overlaps with the start of Major League Baseball's regular season of play, fans were heard sarcastically chanting "Let's go Blue Jays!" as a sign of their shift in priority from an under-performing team to the 2016 Blue Jays season.[159][160][161]

Many Leafs fans live outside the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), and throughout Ontario, including the Ottawa Valley, the Niagara Region, and Southwestern Ontario.[162][163][164] As a result, Leafs’ road games at the Canadian Tire Centre in Ottawa, KeyBank Center in Buffalo, and at the Little Caesars Arena in Detroit host a more neutral attendance. This is due in part to the Leafs fans in those areas, those cities' proximity to the GTA, and the relative ease in getting tickets to those teams' games.[165][166][167]

The Leafs are also a popular team in Atlantic Canada. In November 2016, a survey was conducted that found 20 percent of respondents from Atlantic Canada viewed the Leafs as their favourite team; second only to the Montreal Canadiens at 26 percent.[168] The Leafs were found to be the most favoured team in Prince Edward Island, with 24 percent of respondents favouring the Leafs; and the second favourite team in Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador (19 and 24 percent respectively, both trailing respondents who favoured the Canadiens by one percent).[168]

Rivalries

During the 25 years of the Original Six-era (1942–67), teams played each other 14 times during the regular season, and with only four teams continuing into the playoffs, rivalries were intense. As one of this era's most successful teams, the Maple Leafs established historic rivalries with the two other most successful teams at the time, the Montreal Canadiens and the Detroit Red Wings.[170] In addition to the Canadiens and Red Wings, the Maple Leafs have also developed a rivalry with the Ottawa Senators.[171]

Detroit Red Wings

The Detroit Red Wings and the Maple Leafs are both Original Six teams, playing their first game together in 1927. From 1929 to 1993, the teams met each other in the 16 playoff series, as well as seven Stanley Cup Finals. Meeting one another for a combined 23 times in the postseason, they have played each other in more postseason series than any other two teams in NHL history with the exception of the Bruins and Canadiens who have played a total of 34 postseason series.[172] Overlapping fanbases, particularly in markets such as Windsor, Ontario, have added to the rivalry.[163]

The rivalry between the Detroit Red Wings and the Maple Leafs was at its height during the Original Six-era.[169] The Leafs and Red Wings met in the postseason six times during the 1940s, including four Stanley Cup finals. The Leafs beat the Red Wings in five of their six meetings.[173] In the 1950s, the Leafs and Red Wings met one another in six Stanley Cup semifinals; the Red Wings beat the Leafs in five of their six meetings.[174] From 1961 to 1967, the two teams met one another in three playoff series, including two Stanley Cup finals.[175] Within those 25 years, the Leafs and Red Wings played a total of 15 postseason series including six Cup Finals; the Maple Leafs beat the Red Wings in all six Cup Finals.[176]

The teams have only met three times in the postseason since the Original Six-era, with their last meeting in 1993.[177] After the Leafs moved to the Eastern Conference in 1998, they faced each other less often, and the rivalry began to stagnate. The rivalry became intradivisional once again in 2013, when Detroit was moved to the Atlantic division of the Eastern Conference as part of a realignment.[178]

Montreal Canadiens

The rivalry between the Montreal Canadiens and the Maple Leafs is the oldest in the NHL, featuring two clubs that were active since the inaugural NHL season in 1917.[179] In the early 20th century, the rivalry was an embodiment of a larger culture war between English Canada and French Canada.[180] The Canadiens have won 24 Stanley Cups, while the Maple Leafs have won 13, ranking them first and second for most Cup wins.[179]

The height of the rivalry was during the 1960s, when the Canadiens and Leafs combined to win all but one Cup. The two clubs had 15 postseason meetings. However, failing to meet each other in the playoffs since 1979, the rivalry has waned.[179] It also suffered when Montreal and Toronto were placed in opposite conferences in 1981, with the Leafs in the Clarence Campbell/Western Conference and the Canadiens in the Prince of Wales/Eastern Conference. In 1998, the Leafs were moved into the Eastern Conference's Northeast Division.[181]

The rivalry's cultural imprint may be seen in literature and art. The rivalry from the perspective of the Canadiens fan is perhaps most famously captured in the popular Canadian short story "The Hockey Sweater" by Roch Carrier. Originally published in French as "Une abominable feuille d'érable sur la glace" ("An abominable maple leaf on the ice"), it referred to the Maple Leafs sweater a mother forced her son to wear.[180] The son is presumably based on Carrier himself when he was young.[182] This rivalry is also evident in Toronto's College subway station, which displays murals depicting the two teams, one on each platform.[183]

Ottawa Senators

The modern Ottawa Senators entered the NHL in 1992, but the rivalry between the two teams did not begin to emerge until the late 1990s. From 1992 to 1998, Ottawa and Toronto played in different conferences (Eastern and Western respectively), which meant they rarely played each other. However, before the 1998–99 season, the conferences and divisions were realigned, with Toronto moved to the Eastern Conference's Northeast Division with Ottawa.[181] From 2000 to 2004, the teams played four post-season series; the Leafs won all four playoff series.[171] Due in part to the number Leafs fans living in the Ottawa Valley, and in part to Ottawa's proximity to Toronto, Leafs–Senators games at the Canadian Tire Centre in Ottawa hold a more neutral audience.[184][165][185]

Team information

Broadcasters

As a result of both Bell Canada and Rogers Communications having an ownership stake in MLSE, Maple Leafs broadcasts are split between the two media companies; with regional TV broadcasts split between Rogers' Sportsnet Ontario and Bell's TSN4.[4][186] Colour commentary for Bell's television broadcasts is performed by Jamie McLennan and Ray Ferraro, while play-by-play is provided by Chris Cuthbert and Gord Miller. Colour commentary for Rogers' television broadcasts is performed by Greg Millen, while play-by-play is provided by Paul Romanuk.[187][188] MLSE also operates a regional specialty channel, the Leafs Nation Network.[189] The Leafs Nation Network broadcasts programming related to the Maple Leafs, as well as games for the Toronto Marlies, the Maple Leafs' American Hockey League affiliate.[190]

Like the Maple Leafs television broadcasts, radio broadcasts are split evenly between Rogers' CJCL (Sportsnet 590, The Fan) and Bell's CHUM (TSN Radio 1050).[4] Both Bell and Rogers' radio broadcasts have their colour commentary provided by Jim Ralph, with play-by-play provided by Joe Bowen. Foster Hewitt was the Leafs' first play-by-play broadcaster, providing radio play-by-play from 1927 to 1978. In addition, he provided play-by-play for television from 1952 to 1958, and colour commentary from 1958 to 1961.[191] Originally aired over CFCA, Hewitt's broadcast was picked up by the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (the CRBC) in 1933, moving to CBC Radio (the CRBC's successor) three years later.[192] As the show was aired on Canadian national radio, Hewitt became famous for the phrase "He shoots, he scores!" as well as his sign-on at the beginning of each broadcast, "Hello, Canada, and hockey fans in the United States and Newfoundland."[note 2][193]

Home arenas and practice facilities

| Home arenas | |

| Arena | Tenure |

|---|---|

| Arena Gardens | 1917–1931 |

| Maple Leaf Gardens | 1931–1999 |

| Scotiabank Arena | 1999–present |

The team's first home was the Arena Gardens, later known as the Mutual Street Arena. From 1912 until 1931, the Arena was ice hockey's premier site in Toronto.[194] The Arena Gardens was the third arena in Canada to feature a mechanically-frozen, or artificial, ice surface, and for 11 years was the only such facility in Eastern Canada.[195] The Arena was demolished in 1989, with most of the site converted to residential developments.[196] In 2011, parts of the site were made into a city park, known as Arena Gardens.[197]

In 1931, over a six-month period, Conn Smythe built Maple Leaf Gardens on the northwest corner of Carlton Street and Church Street, at a cost of C$1.5 million (C$23.9 million in 2018).[198] The arena soon acquired nicknames including the "Carlton Street Cashbox", and the "Maple Leaf Mint", since the team's games were constantly sold out.[199] The Maple Leafs won 11 Stanley Cups while playing at the Gardens. The first annual NHL All-Star Game was also held at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1947.[200] The Gardens opened on November 12, 1931, with the Maple Leafs losing 2–1 to the Chicago Blackhawks.[34] On February 13, 1999, the Maple Leafs played their last game at the Gardens, suffering a 6–2 loss to the Blackhawks.[97] The building is presently used as a multi-purpose facility, with a Loblaws grocery store occupying retail space on the lower floors, and an athletics arena for Ryerson University, occupying another level.[201][202]

The Maple Leafs presently use two facilities in the City of Toronto. The club moved from the Gardens on February 20, 1999, to their current home arena, the Scotiabank Arena, a multi-purpose indoor entertainment arena on Bay Street in Downtown Toronto.[203] The arena is owned by the Maple Leafs' parent company MLSE, and is shared with the NBA's Toronto Raptors (another MLSE subsidiary), as well as the National Lacrosse League's Toronto Rock.[204] In addition to the main arena, the Maple Leafs also operate a practice facility at the MasterCard Centre for Hockey Excellence. Opened in 2009 by the Lakeshore Lions Club, the arena adopted the name of the Lions' old arena, the Lakeshore Lions Arena. Facing financial difficulties, in September 2011, the City of Toronto took over ownership of the arena from the Lions' Club. It is now a City of Toronto controlled Corporation.[205][206] Renamed the Mastercard Centre, the facility has three NHL rinks and one Olympic-sized rink.[206]

Logo and uniform

The team is represented through a number of images and symbols, including the maple leaf logo found on the club's uniform, and their mascot. The Maple Leafs' jersey has a long history and is one of the best-selling NHL jerseys among fans.[207] The club's uniforms have been altered several times. The club's first uniforms were blue and featured the letter T.[208] The first major alteration came in 1919, when the club was renamed the St. Patricks. The uniforms were green with "Toronto St. Pats" on the logo, lettered in green either on a white "pill" shape or stripes.[18][209]

When the club was renamed the Maple Leafs in the 1927–28 season, the logo was changed, and the team reverted to blue uniforms.[30] The logo was a 48-point maple leaf with the words lettered in white. The home jersey was blue with alternating thin-thick stripes on the arms, legs and shoulders. The road uniform was white with three stripes on the chest and back, waist and legs.[210] For 1933–34, the alternating thin-thick stripes were replaced with stripes of equal thickness. This remained the basic design for the next 40 years.[210] In 1937, veins were added to the leaf and "Toronto" curved downwards at the ends instead of upwards.[211] In 1942, the 35-point leaf was introduced. In 1946, the logo added trimming to the leaf with a white or blue border, while "C" for captain and "A" for alternate captain first appeared on the sweaters. In 1947, the "Toronto Maple Leafs" lettering was in red for a short time. In 1958, a six-eyelet lace and tie was added to the neck and a blue shoulder yoke was added. In 1961, player numbers were added on the sleeves.[212]

The fourth major change came in the 1966–67 season, when the logo was changed to an 11-point leaf, similar to the leaf on the then-new flag of Canada to commemorate the Canadian Centennial.[212] The simpler leaf logo featured the Futura Display typeface, replacing the previous block letters. The stripes on the sleeves and waistline were also changed, adding a wider stripe in between the two thinner stripes (similar to the stripe patterns on the socks and on the early Leafs sweaters). Before the 1970–71 season, the Leafs adopted a new 11-point leaf logo, with a Kabel bold-font "Toronto" going straight across, running parallel to the other words. Other changes to the sweater included the replacement of the arm strips with an elongated yoke that extended to the ends of the sleeves, a solid single stripe on the waist replacing the three waistline stripes, two stripes on the stockings, and a smaller, textless Leaf crest on the shoulders.[213] In 1973, the jersey's neck was a lace tie-down design, before the V-neck returned in 1976. In 1977, the NHL rules were changed to require names on the backs of the uniforms, but Harold Ballard resisted the change. Under Ballard's direction, the team briefly "complied" with the rule by placing blue letters on the blue road jersey for a game on February 26, 1978. With the NHL threatening hefty fines for failing to comply with the spirit of the rule (namely, having the names be legible for the fans and broadcasters in attendance), Ballard reached a compromise with the league, allowing the Leafs to finish the 1977–78 season with contrasting white letters on the road sweaters, and coming into full compliance with the new rule in the 1978–79 season by adding names in blue to the white home sweaters.[213]

With the NHL's 75th anniversary season (1991–92 season), the Leafs wore "Original Six" style uniforms similar to the designs used in the 1940s.[213] Because of the fan reaction to the previous season's classic uniforms, the first changes to the Maple Leafs uniform in over twenty years were made. The revised uniforms for 1992–93 featured two stripes on the sleeves and waistline like the classic uniform, but with the 1970 11-point leaf with Kabel text on the front. A vintage-style veined leaf crest was placed on the shoulders.[213] The uniforms would undergo a few modifications over the years.

.jpg)

In 1997, Nike acquired the rights to manufacture Maple Leafs uniforms. Construction changes to the uniform included a wishbone collar and pothole mesh underarms, while the player name and number font was changed to Kabel to match the logo. CCM returned to manufacturing the Leafs uniforms in 1999 when Nike withdrew from the hockey jersey market, and kept most of the changes, although in 2000 the Kabel numbers were replaced with block numbers outlined in silver, and a silver-outlined interlocked TML monogram replaced the vintage leaf on the shoulders. Also during this time, the Leafs began wearing a white 1960s-style throwback third jersey featuring the outlined 35-point leaf, blue shoulders, and lace-up collar.

With Reebok taking over the NHL jersey contract following the 2004-05 lockout, changes were expected when the Edge uniform system was set to debut in 2007. As part of the Edge overhaul, the TML monograms were removed from the shoulders, the silver outlines on the numbers were replaced with blue or white outlines (e.g. the blue home jersey featured white numbers with blue and white outlines, rather than blue and silver), and the waistline stripes were removed. In 2010, the two waistline stripes were restored, the vintage leaf returned to the shoulders, and the player names and numbers were changed again, reverting to a simpler single-color block font. Finally, lace-up collars were brought back to the primary uniforms.[207][214] The Leafs also brought back the 1967-70 blue uniform, replacing the white 1960s jersey as their third uniform. For the 2014 NHL Winter Classic the Leafs wore a sweater inspired by their earlier uniforms in the 1930s.[214]

On February 2, 2016, the team unveiled a new logo for the 2016–17 season in honour of its centennial, dropping the use of the Kabel-style font lettering used from 1970; it returns the logo to a form inspired by the earlier designs, with 31 points to allude to the 1931 opening of Maple Leaf Gardens, and 17 veins a reference to its establishment in 1917. 13 of the veins are positioned along the top part in honour of its 13 Stanley Cup victories. The logo was subsequently accompanied by a new uniform design that was unveiled during the 2016 NHL Entry Draft on June 24, 2016.[215][216][217] In addition to the new logo, the new uniforms feature a custom block typeface for the player names and numbers. Two stripes remain on the sleeves, with a single stripe at the waistline. The updated design carried over to the Adidas Adizero uniform system in 2017.

The Maple Leafs have in recent years occasionally worn a St. Pats throwback uniform for select games in 2003 and 2017, the latter as part of the franchise's centennial celebration. For the 2018 season, the Leafs also wore a Toronto Arenas-inspired throwback design. In addition, the Leafs participated in two outdoor games as part of the NHL's own centennial celebration. In the NHL Centennial Classic against the Red Wings, the Leafs wore blue sweaters with bold white stripes across the chest and arms. For the 2018 NHL Stadium Series, the Leafs wore white uniforms with two blue stripes across the chest and arms, and in an unusual move, paired this uniform with white pants.

Mascot

The Maple Leafs' mascot is Carlton the Bear, an anthropomorphic polar bear whose name and number (#60) comes from the location of Maple Leaf Gardens at 60 Carlton Street, where the Leafs played throughout much of their history.[218] Carlton made his first public appearance on July 29, 1995. He later made his regular season appearance on October 10, 1995.[219]

Minor league affiliates

The Maple Leafs are presently affiliated with two minor league teams, the Toronto Marlies of the American Hockey League, and the Newfoundland Growlers of the ECHL. The Marlies play from Coca-Cola Coliseum in Toronto. Prior to its move to Coca-Cola Coliseum in 2005, the team was located in St. John's, Newfoundland and was known as the St. John's Maple Leafs.[220] The Marlies originated from the New Brunswick Hawks, who later moved to St. Catherines, Newmarket, and St. John's, before finally moving to Toronto.[221][222] The Marlies was named after the Toronto Marlboros, a junior hockey team named after the Duke of Marlborough.[220] Founded in 1903, the Marlboros were sponsored by the Leafs from 1927 to 1989.[220][223] The Marlboros constituted one of two junior hockey teams the Leafs formerly sponsored, the other being the Toronto St. Michael's Majors.[51]

The Growlers are an ECHL team based in St. John's Newfoundland. The Growlers became affiliated with the Maple Leafs and the Marlies in June 2018, and are presently their only NHL and AHL affiliates.[224] Unlike the Marlies, the Growlers are not owned by the Leafs' parent company, but are instead owned by a local ownership group in St. John's called Deacon Investments Limited.

Ownership

The Maple Leafs is one of six professional sports teams owned by Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment (MLSE). Initially ownership of the club was held by the Arena Gardens of Toronto, Limited; an ownership group fronted by Henry Pellatt, that owned and managed Arena Gardens.[225] The club was named a permanent franchise in the League following its inaugural season, with team manager Charles Querrie, and the Arena Gardens treasurer Hubert Vearncombe as its owners.[226] The Arena Company owned the club until 1919, when litigations from Eddie Livingstone forced the company to declare bankruptcy. Querrie brokered the sale of the Arena Garden's share to the owners of the amateur St. Patricks Hockey Club.[227][228] Maintaining his shares in the club, Querrie fronted the new ownership group until 1927, when the club was put up for sale. Toronto Varsity Blues coach Conn Smythe put together an ownership group and purchased the franchise for $160,000.[23] In 1929, Smythe decided, in the midst of the Great Depression, that the Maple Leafs needed a new arena.[33][34] To finance it, Smythe launched Maple Leaf Gardens Limited (MLGL), a publicly traded management company to own both the Maple Leafs and the new arena, which was named Maple Leaf Gardens. Smythe traded his stake in the Leafs for shares in MLGL, and sold shares in the holding company to the public to help fund construction of the arena.[229]

Although Smythe was the face of MLGL from its founding, he did not gain controlling interest in the company until 1947.[230][231][232] Smythe remained principal until 1961, when he sold 90 percent of his shares to an ownership group consisting of Harold Ballard, John Bassett, and Stafford Smythe. Ballard became majority owner in February 1972, shortly following the death of Stafford Smythe.[75] Ballard was the principal owner of MLGL until his death in 1990. The company remained a publicly traded company until 1998, when an ownership group fronted by Steve Stavro privatized the company by acquiring more than the 90 percent of stock necessary to force objecting shareholders out.[233][234]

While initially primarily a hockey company, with ownership stakes in a number of junior hockey clubs including the Toronto Marlboros of the Ontario Hockey Association, the company later branched out to own the Hamilton Tiger-Cats of the Canadian Football League from the late 1970s to late 1980s.[235] On February 12, 1998, MLGL purchased the Toronto Raptors of the National Basketball Association, who were constructing the then-Air Canada Centre. After the Raptors purchase, MLGL changed names to MLSE.[94] The company's portfolio has since expanded to include the Toronto FC of Major League Soccer, the Toronto Marlies of the AHL, the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League and a 37.5 percent stake in Maple Leaf Square.[236]

The present ownership structure emerged in 2012, after the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (the company's former principal owner) announced the sale of its 75 percent stake in MLSE to a partnership between Bell Canada and Rogers Communications, in a deal valued at $1.32 billion.[237] As part of the sale, two numbered companies were created to jointly hold stock. This ownership structure ensures that, at the shareholder level, Rogers and Bell vote their overall 75 percent interest in the company together and thus decisions on the management of the company must be made by consensus between the two.[238] The remaining 25 percent is owned by Larry Tanenbaum, who is also the chairman of MLSE.[237] Bell's pension fund owns a portion of Bell's share of MLSE, in order to retain its existing 18 percent interest in the Montreal Canadiens; as NHL rules prevent any shareholder that owns more than 30 percent of a team from holding an ownership position in another.[239]

| Ownership structure of Maple Leafs Sports & Entertainment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Season-by-season record

This is a partial list of the last five seasons completed by the Maple Leafs. For the full season-by-season history, see List of Toronto Maple Leafs seasons

Note: GP = Games played, W = Wins, L = Losses, T = Ties, OTL = Overtime Losses, Pts = Points, GF = Goals for, GA = Goals against

| Season | GP | W | L | OTL | Pts | GF | GA | Finish | Playoffs |

| 2013–14 | 82 | 38 | 36 | 8 | 84 | 231 | 256 | 6th, Atlantic | Did not qualify |

| 2014–15 | 82 | 30 | 44 | 8 | 68 | 211 | 262 | 7th, Atlantic | Did not qualify |

| 2015–16 | 82 | 29 | 42 | 11 | 69 | 198 | 246 | 8th, Atlantic | Did not qualify |

| 2016–17 | 82 | 40 | 27 | 15 | 95 | 251 | 242 | 4th, Atlantic | Lost in First Round, 2–4 (Capitals) |

| 2017–18 | 82 | 49 | 26 | 7 | 105 | 277 | 232 | 3rd, Atlantic | Lost in First Round, 3–4 (Bruins) |

Players and personnel

Current roster

Updated October 8, 2018[240][241]

Team captains

There have been twenty-one team captains throughout the team's history.[242] Ken Randall served as the team's first captain in the inaugural 1917–18 NHL season.[242] The first captain to have served the position for multiple seasons was Reg Noble, serving as captain from 1920 to 1924.[242] John Ross Roach was the first goaltender to be named captain in the NHL, and the only goaltender to serve as the Leafs' captain.[243][242] He was one of only six goalies in NHL history to have been officially recognized as the team captain. George Armstrong, captain from 1958 through 1969, was the longest serving captain in the team's history.[244] In 1997, Mats Sundin became the first non-Canadian to captain the Maple Leafs. His tenure as captain holds the distinction as the longest captaincy for a non-North American born player in NHL history.[245] The last player named to the position was Dion Phaneuf on June 14, 2010. No replacement has been named since he was traded on February 9, 2016.[123][138]

Three captains of the Maple Leafs have held the position at different points in their career. Syl Apps' first tenure as the captain began from 1940 to 1943, before he stepped down and left the club to enlist in the Canadian Army. Bob Davidson served as the Maple Leafs captain until Apps' return from the Army in 1945, when he resumed his captaincy until 1948.[246] Ted Kennedy's first tenure as captain was from 1948 to 1955. He announced his retirement from the sport at the end of the 1954–55 season, with Sid Smith succeeding him as captain.[242] Although Kennedy missed the entire 1955–56 season, he came out of retirement to play the second half of the 1956–57 season. During that half season, Kennedy served his second tenure as the Maple Leafs' captain.[247] Darryl Sittler was the third player to have been named the team's captain twice. As a result of a dispute between Sittler and the Maple Leafs' general manager Punch Imlach, Sittler relinquished the captaincy on December 29, 1979. The dispute was resolved in the following off-season, after a heart attack hospitalized Imlach. Sittler arranged talks with Ballard to resolve the issue, eventually resuming his captaincy on September 24, 1980.[248] No replacement captain was named during the interim period.[249]

|

|

|

|

Head coaches

The Maple Leafs have had 39 head coaches (including four interim coaches).[242] The franchise's first head coach was Dick Carroll, who coached the team for two seasons.[242] A number of coaches have served as the Leafs head coach on multiple occasions. King Clancy was named the head coach on three separate occasions while Charles Querrie and Punch Imlach served the position on two occasions.[242] Mike Babcock is the current head coach. He was named as coach on May 20, 2015, signing an eight-year $50-million contract, becoming the highest paid NHL coach in history.[250] Earning 105 points during the 2017–18 season, Babcock recorded the most points of any Maple Leafs' coach in a single season.[141]

Punch Imlach coached the most regular season games of any Leafs' head coach with 770 games, and has the most all-time points with the Maple Leafs, with 865.[242] He is followed by Pat Quinn, who coached 574 games, with 678 points all-time with the Maple Leafs.[242] Both Mike Rodden and Dick Duff, have the fewest points with the Maple Leafs, with 0. Both were interim coaches who coached only two games each in 1927 and 1980 respectively, losing both games.[242] Five Maple Leafs' coaches have been inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as players, while four others were inducted as builders. Pat Burns is the only Leafs' head coach to win a Jack Adams Award with the team.[251]

Draft picks

In the 1963 NHL Amateur Draft, the NHL's inaugural draft, the Maple Leafs selected Walt McKechnie, a centre from the London Nationals with their first pick, sixth overall.[252] Two Maple Leafs captains were obtained through the draft, Darryl Sittler in the 1970 draft; as well as Wendel Clark in the 1985 NHL Entry Draft.[253] The Maple Leafs have drafted two players with a first overall draft pick; Clark in the 1985 draft, and Auston Matthews in the 2016 draft.[254] Rasmus Sandin was the most recent player selected by the Maple Leafs in the first round, using the twenty-ninth overall pick at the 2018 draft.[255]

Team and league honours

| No. | Player | Position | Tenure | Date of honour[256] | Date of retirement[257] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Turk Broda | G | 1935–1943 1946–1951[note 3] | March 11, 1995 | October 15, 2016 |

| 1 | Johnny Bower | G | 1958–1969 | March 11, 1995 | October 15, 2016 |

| 4 | Hap Day | D | 1924–1937 | October 4, 2006 | October 15, 2016 |

| 4 | Red Kelly | C | 1960–1967 | October 4, 2006 | October 15, 2016 |

| 5 | Bill Barilko | D | 1945–1951[note 3] | Not honoured | October 17, 1992[258] |

| 6 | Ace Bailey | RW | 1926–1933[note 3] | Not honoured | February 14, 1934 |

| 7 | King Clancy | D | 1930–1937 | November 21, 1995 | October 15, 2016 |

| 7 | Tim Horton | D | 1949–1970 | November 21, 1995 | October 15, 2016 |

| 9 | Charlie Conacher | RW | 1929–1938 | February 28, 1998 | October 15, 2016 |

| 9 | Ted Kennedy | C | 1942–1955 1956–1957[note 3] | October 3, 1993 | October 15, 2016 |

| 10 | Syl Apps | C | 1936–1943 1945–1948[note 3] | October 3, 1993 | October 15, 2016 |

| 10 | George Armstrong | RW | 1949–1971[note 3] | February 28, 1998 | October 15, 2016 |

| 13 | Mats Sundin | C | 1994–2008 | February 11, 2012 | October 15, 2016 |

| 14 | Dave Keon | C | 1960–1975 | Not honoured | October 15, 2016 |

| 17 | Wendel Clark | LW | 1985–1994 1996–1998 2000 | November 22, 2008 | October 15, 2016 |

| 21 | Borje Salming | D | 1973–1989 | October 4, 2006 | October 15, 2016 |

| 27 | Frank Mahovlich | LW | 1956–1968 | October 3, 2001 | October 15, 2016 |

| 27 | Darryl Sittler | C | 1970–1982 | February 8, 2003 | October 15, 2016 |

| 93 | Doug Gilmour | C | 1992–1997 | January 31, 2009 | October 15, 2016 |

| Player elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame |

| Number retired for multiple players |

| Number was not honoured before being retired |

Retired numbers

The Maple Leafs have retired the numbers of 19 players (as some players used the same number, only 13 numbers have been retired).[257] Between October 17, 1992, and October 15, 2016, the Maple Leafs took a unique approach to retired numbers. Whereas players who suffered a career ending injury had their numbers retired, "great" players had their number "honoured".[258] Honoured numbers remained in general circulation for players, however, during Brian Burke's tenure as the Maple Leafs' general manager, use of honoured numbers required his approval.[259]

During this period, only two players met the criteria, the first being number 6, worn by Ace Bailey and retired on February 14, 1934; and Bill Barilko's number 5, retired on October 17, 1992.[258] The retirement of Bailey's number holds the distinction of being the first of its kind in professional sports.[260][261] It was briefly taken out of retirement before to the 1968–69 season, after he asked that Ron Ellis be allowed to wear his number.[262] Bailey's number returned to retirement after Ellis's final game on January 14, 1981.[263]

The first players to have their numbers honoured were Syl Apps and Ted Kennedy, on October 3, 1993.[258] Mats Sundin was the last player to have his number honoured on February 11, 2012.[264] On October 15, 2016, before the home opening game of the team's centenary season, the Maple Leafs announced they had changed their philosophy on retiring numbers, and that the numbers of those 16 honoured players would now be retired, in addition to the retirement of Dave Keon's number.[257]

As well as honouring and retiring the numbers, the club also commissioned statues of former Maple Leafs. The group of statues, known as Legends Row, is a 9.2 metres (30 ft) granite hockey bench with statues of former club players. Unveiled in September 2014, it is located outside Gate 5 of Scotiabank Arena, at Maple Leaf Square.[265] As of October 2017, statues have been made of 14 players with retired numbers.[266]

In addition to the thirteen numbers retired by the Maple Leafs, the number 99 is also retired from use in the organization. At the 2000 NHL All-Star Game hosted in Toronto, the NHL announced the League-wide retirement of Wayne Gretzky's number 99, retiring it from use throughout all its member teams, including the Maple Leafs.[267]

Hall of Famers

The Toronto Maple Leafs acknowledges an affiliation with 75 inductees of the Hockey Hall of Fame.[268][269] The 75 inductees include 62 former players as well as 13 builders of the sport. The Maple Leafs have the greatest number of players inducted in the Hockey Hall of Fame of any NHL team.[270] The 13 individuals recognized as builders of the sport include former Maple Leafs broadcasters, executives, head coaches, and other personnel relating to the club's operations. Inducted in 2017, Dave Andreychuk was the latest Maple Leafs player to be inducted in the Hockey Hall of Fame.[271]

In addition to players and builders, four broadcasters for the Maple Leafs were also awarded the Foster Hewitt Memorial Award from the Hockey Hall of Fame.[272] In 1984, Foster Hewitt, a radio broadcaster, was awarded the Hall of Fame's inaugural Foster Hewitt Memorial Award, an award named after Hewitt. Hewitt was already inducted as a builder in the Hall of Fame prior to the award's inception.[192] Other Maple Leafs broadcasters that received the award include Wes McKnight in 1986, Bob Cole in 2007, and Bill Hewitt in 2007.[272]

Franchise career leaders

These are the top franchise leaders in regular season points, goals, assists, points per game, games played, and goaltending wins as of the end of the 2015–16 season.[273]

- * – current Maple Leafs player

| Player | Seasons | GP | TOI | W | L | T | OT | GA | GAA | SA | SV% | SO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turk Broda | 1935–1943 1946–1951 | 629 | 38,167 | 302 | 224 | 101 | — | 1,609 | 2.53 | — | — | 62 |

| Johnny Bower | 1945–1969 | 475 | 27,396 | 219 | 160 | 79 | — | 1,139 | 2.49 | 14,607[note 4] | .922[note 4] | 32 |

| Felix Potvin | 1991–1999 | 369 | 21,641 | 160 | 149 | 49 | — | 1,026 | 2.87 | 11,133 | .908 | 12 |

| Curtis Joseph | 1998–2002 | 270 | 15,808 | 138 | 97 | 28 | — | 656 | 2.49 | 7,257 | .910 | 17 |

| Mike Palmateer | 1976–1984 | 296 | 16,868 | 129 | 112 | 41 | — | 964 | 3.43 | 8,886 | .849 | 15 |

| Harry Lumley | 1952–1956 | 267 | 16,007 | 103 | 106 | 58 | — | 586 | 2.20 | 1,696[note 4] | .907[note 4] | 34 |

| Lorne Chabot | 1928–1933 | 215 | 13,126 | 103 | 79 | 31 | — | 475 | 2.17 | — | — | 31 |

| John Ross Roach | 1921–1928 | 222 | 13,674 | 98 | 107 | 17 | — | 639 | 2.80 | — | — | 13 |

| Ed Belfour | 2002–2006 | 170 | 10,079 | 93 | 61 | 11 | 4 | 422 | 2.51 | 4,775 | .912 | 17 |

| James Reimer | 2010–2016 | 207 | 11,176 | 85 | 76 | — | 23 | 528 | 2.83 | 6,118 | .914 | 11 |

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ The Presidents' Trophy was not introduced until 1985. Had the trophy existed since league inception, the Maple Leafs franchise would have won six Presidents' Trophies. The winning seasons would have included 1917–18, 1920–21, 1933–1934, 1934–35, 1947–48, and 1962–63

- ↑ The Dominion of Newfoundland did not join Canadian Confederation until March 31, 1949. Newfoundland was a separate Dominion of the British Empire from 1907 to 1949.