New Brunswick

| New Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick (French) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

Motto(s): Latin: Spem reduxit[1] ("Hope restored") | |||

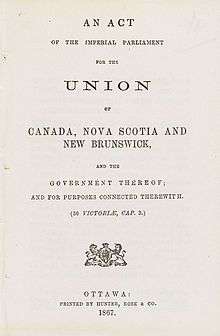

| Confederation | July 1, 1867 (1st, with Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia) | ||

| Capital | Fredericton | ||

| Largest city | Moncton | ||

| Largest metro | Greater Moncton | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Constitutional monarchy | ||

| • Lieutenant Governor | Jocelyne Roy-Vienneau | ||

| • Premier | Brian Gallant (Liberal) | ||

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick | ||

| Federal representation | (in Canadian Parliament) | ||

| House seats | 10 of 338 (3%) | ||

| Senate seats | 10 of 105 (9.5%) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 72,907 km2 (28,150 sq mi) | ||

| • Land | 71,450 km2 (27,590 sq mi) | ||

| • Water | 1,458 km2 (563 sq mi) 2% | ||

| Area rank | Ranked 11th | ||

| 0.7% of Canada | |||

| Population (2016) | |||

| • Total | 747,101 [2] | ||

| • Estimate (2018 Q3) | 770,633 [3] | ||

| • Rank | Ranked 8th | ||

| • Density | 10.46/km2 (27.1/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) |

New Brunswicker FR: Néo-Brunswickois(e) | ||

| Official languages | [4] | ||

| GDP | |||

| • Rank | 9th | ||

| • Total (2011) | C$32.180 billion[5] | ||

| • Per capita | C$42,606 (11th) | ||

| Time zone | Atlantic: UTC−4/−3 | ||

| Postal abbr. | NB | ||

| Postal code prefix | E | ||

| ISO 3166 code | CA-NB | ||

| Flower | Purple violet | ||

| Tree | Balsam fir | ||

| Bird | Black-capped chickadee | ||

| Website |

www | ||

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |||

New Brunswick (French: Nouveau-Brunswick; Canadian French pronunciation: [nuvobʁɔnzwɪk] (![]()

The indigenous inhabitants of the land at the time of European colonization were the Mi'kmaq, the Maliseet, and the Passamaquoddy peoples, aligned politically within the Wabanaki Confederacy, many of whom still reside in the area.

Being relatively close to Europe, New Brunswick was among the first places in North America to be explored and settled, starting with the French in the early 1600s, who eventually colonized most of the Maritimes and some of Maine as the colony of Acadia. The area was caught up in the global conflict between the British and French empires, including the 1722–25 Dummer's War against New England. In 1755 what is now New Brunswick was claimed by the British as part of Nova Scotia, to be partitioned off in 1784 following an influx of refugees from the American Revolutionary War. Large groups of English, Scottish, and French people had settled and become the majority population by this time. However, as the Catholic French and indigenous peoples had intermarried heavily, they were essentially a Métis.

In 1785, Saint John became the first incorporated city in what is now Canada.[6] The same year, the University of New Brunswick became one of the first universities in North America. The province prospered in the early 1800s due to logging, shipbuilding, and related activities. The population grew rapidly in part due to waves of Irish immigration to Saint John and Miramichi regions, reaching about a quarter of a million by mid-century. In 1867 New Brunswick was one of four founding provinces of Canada, along with Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario.

After Confederation, wooden shipbuilding and lumbering declined, while protectionist policy disrupted traditional economic patterns with New England. The mid-1900s found New Brunswick to be one of the poorest regions of Canada, but that has been mitigated somewhat by federal transfer payments and improved support for rural areas.

As of 2002, provincial gross domestic product was derived as follows: services (about half being government services and public administration) 43%; construction, manufacturing, and utilities 24%; real estate rental 12%; wholesale and retail 11%; agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, mining, oil and gas extraction 5%; transportation and warehousing 5%.[7]

According to the Constitution of Canada New Brunswick is the only bilingual province. About two thirds of the population declare themselves anglophones and a third francophones. One third of the overall population describe themselves as bilingual. Atypically for Canada, only about half of the population lives in urban areas, mostly in Greater Moncton, Greater Saint John and the capital Fredericton.

Unlike the other Maritime provinces, New Brunswick's terrain is mostly forested uplands, with much of the land further from the coast, giving it a harsher climate. New Brunswick is 83% forested, and less densely-populated than the rest of the Maritimes.

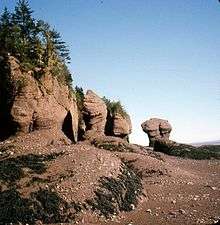

Tourism accounts for about 9% of the labour force directly or indirectly. Popular destinations include Fundy National Park and the Hopewell Rocks, Kouchibouguac National Park, and Roosevelt Campobello International Park. In 2013, 64 cruise ships called at Port of Saint John carrying on average 2600 passengers each.[8]

History

Pre-history

Indigenous peoples have been present in the area since about 7000 BC. At the time of European contact, inhabitants were the Mi'kmaq, the Maliseet, and the Passamaquoddy. Although these tribes did not leave a written record, their language is present in many placenames, such as Aroostook, Bouctouche, Petitcodiac, Quispamsis, and Shediac.

New Brunswick may have been part of Vinland, the area explored by Norwegian Vikings, and the Bay of Fundy may have been visited in the early 1500s by Basque, Breton, and Norman fishermen.[9]

French colony

The first documented European visits were by Jacques Cartier in 1534. A party led by Pierre du Gua de Monts and Samuel de Champlain visited the mouth of the Saint John River on the eponymous Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day in 1604. Now Saint John, this was later the site of the first permanent European settlement in New Brunswick.[9] French settlement extended up the river to the site of present-day Fredericton.

Other settlements in the southeast extended from Beaubassin, near the present-day border with Nova Scotia, and extending to Baie Verte, and up the Petitcodiac, Memramcook, and Shepody Rivers.[10]

By the early 1700s the area that is now New Brunswick was part of the French colony of Acadia, which was in turn part of New France. Acadia comprised most of what is now the Maritimes, as well as parts of Québec and Maine. The peace and prosperity of the colony was ended by rivalry between Britain and France for control of territory in Europe and North America starting in the early 1700s. With the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, the part of Acadia today known as peninsular Nova Scotia became another British colony on the eastern seaboard. Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Île-Royale (Cape Breton Island) remained French. The ownership of New Brunswick was disputed, with an informal border on the Isthmus of Chignecto.

To defend the area, especially in the 1722–25 Dummer's War against New England, the French built Fort Nashwaak, Fort Boishebert, Fort Menagoueche in Bay of Fundy, and in the southeast Fort Gaspareaux and Fort Beauséjour. The latter was captured by British and New England troops in 1755, followed soon after by the Expulsion of the Acadians.

British colony

Present-day New Brunswick became part of the colony of Nova Scotia. Hostilities ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, and Acadians returning from exile discovered several thousand immigrants, mostly from New England, on their former lands. Some settled around Memramcook and along the Saint John River.[11]

Settlement was initially slow. Pennsylvanian immigrants founded Moncton in 1766. An American settlement also developed at Saint John, and English settlers from Yorkshire arrived in the Sackville area.

After the American Revolution, about 10,000 loyalist refugees settled along the north shore of the Bay of Fundy,[12] commemorated in the province's motto, Spem reduxit ("hope restored"). In 1784 New Brunswick was partitioned from Nova Scotia, and that year saw its first elected assembly.[13] The colony was named New Brunswick in honour of George III, King of Great Britain, King of Ireland, and Prince-elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg in what is now Germany.[14] In 1785 Saint John became Canada's first incorporated city.[15]

Although New Brunswick has limited arable land, the 1800s saw an age of prosperity based on wood export and shipbuilding,[15] bolstered by The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 and demand from the American Civil War. St. Martins became the third most productive shipbuilding town in the Maritimes, producing over 500 vessels.[16]

The first half of the 1800s saw large-scale immigration from Ireland and Scotland, with the population reaching 252,047 by 1861.

In 1848, responsible home government was granted[13] and the 1850s saw the emergence of political parties largely organised along religious and ethnic lines.[15]

Confederation

The notion of unifying the separate colonies of British North America was discussed increasingly in the 1860s. Many felt that the American Civil war was the result of weak central government, and wished to avoid such violence and chaos.[17] The 1864 Charlottetown Conference had been intended to discuss a Maritime Union, but concerns over possible conquest by the Americans coupled with a belief that Britain was unwilling to defend its colonies against American attack led to a request from the Province of Canada (now Ontario and Quebec) to expand the scope of the meeting. In 1866 the US cancelled the Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty leading to loss of trade with New England and prompting a desire to build trade within British North America,[18] while Fenian raids increased support for union.[19]

On 1 July 1867 New Brunswick entered the Canadian Confederation along with Nova Scotia, Quebec and Ontario.

Modern New Brunswick

Confederation brought into existence the Intercolonial Railway in 1872, a consolidation of the existing Nova Scotia Railway, European and North American Railway, and Grand Trunk Railway. In 1879 John A. Macdonald's Conservatives enacted the National Policy which called for high tariffs and opposed free trade, disrupting the trading relationship between the Maritimes and New England. The economic situation was worsened by the decline of the wooden ship building industry. The railways and tariffs did foster the growth of new industries in the province such as textile manufacturing, iron mills, and sugar refineries,[11] many of which eventually failed to compete with better capitalized industry in central Canada.

In 1937 New Brunswick had the highest infant mortality and illiteracy rates in Canada.[20] At the end of the Great Depression the New Brunswick standard of living was much below the Canadian average. In 1940 the Rowell–Sirois Commission reported that federal government attempts to manage the depression illustrated grave flaws in the Canadian constitution. While the federal government had most of the revenue gathering powers, the provinces had many expenditure responsibilities such as healthcare, education, and welfare, which were becoming increasingly expensive. The Commission recommended the creation of equalization payments, implemented in 1957.

The Acadians in northern New Brunswick had long been geographically and linguistically isolated from the more numerous English speakers to the south. The population of French origin grew dramatically after Confederation, from about 16 per cent in 1871 to 34 per cent in 1931.[21] Government services were often not available in French, and the infrastructure in Francophone areas was less developed than elsewhere. In 1960 Premier Louis Robichaud embarked on the New Brunswick Equal Opportunity program, in which education, rural road maintenance, and healthcare fell under the sole jurisdiction of a provincial government that insisted on equal coverage throughout the province, rather than the former county-based system.

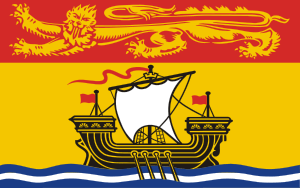

The flag of New Brunswick, based on the coat of arms, was adopted in 1965. The conventional heraldic representations of a lion and a ship represent colonial ties with Europe, and the importance of shipping at the time the coat of arms was assigned.[22]

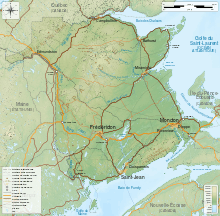

Geography

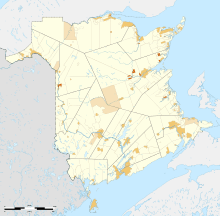

Roughly square, New Brunswick is bordered on the north by Quebec, on the east by the Atlantic Ocean, on the south by the Bay of Fundy, and on the west by the US state of Maine. The southeast corner of the province is connected to Nova Scotia at the isthmus of Chignecto.

Glaciation has left much of New Brunswick's uplands with only shallow, acidic soils which have discouraged settlement, but are home to enormous forests.[23]

Topography

New Brunswick is within the Appalachian Mountains and is divided into:[24]

- The Chaleur Uplands, extending from Maine to the north of the province and drained by the Saint John and Restigouche rivers.

- The Notre Dame Mountains in the northwest corner, where elevation varies from 150 to 610m, there are many small lakes and steep slopes.

- The New Brunswick Highlands, which includes the Caledonia, St. Croix, and Miramichi Highlands.

- The Lowlands in the central and eastern parts. This low-lying area is mostly under 100m above sea level, and altitudes rarely exceed 180m.

All of the rivers of New Brunswick drain either into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the east, or into the Bay of Fundy to the south. These watersheds include lands in Quebec and Maine.[24]

During the glacial period New Brunswick was covered by thick layers of ice. It cut U-shaped valleys in the Saint John and Nepisiguit River valleys, and pushed granite boulders from the Miramichi highlands south and east, leaving them as erratics when the ice receded at the end of the Wisconsin glaciation, along with deposits such as the eskers between Woodstock and St George, today sources of sand and gravel.

Flora and fauna

Most of New Brunswick[24] is forested with secondary forest or tertiary forest. At the start of European settlement, the Maritimes were covered from coast to coast by a forest of mature trees, giants by today's standards. Today less than one per cent of old-growth Acadian forest remains,[25] and the World Wide Fund for Nature lists the Acadian Forest as endangered.[26] Following the frequent large scale disturbances caused by settlement and timber harvesting, the Acadian forest is not growing back as it was, but is subject to borealization. This means that exposure-resistant species that are well adapted to the frequent large scale disturbances common in the boreal forest are increasingly abundant. These include jack pine, balsam fir, black spruce, white birch, and poplar.[26]

Forest ecosystems support large carnivores such as the bobcat, Canada lynx, and black bear, and the large herbivores moose and white-tailed deer.

Fiddlehead greens are harvested from the Ostrich fern which grows on riverbanks.

Furbish's lousewort a perennial herb endemic to the shores of the upper Saint John River, is an endangered species threatened by habitat destruction, riverside development, forestry, littering and recreational use of the riverbank.[27] Many wetlands are being disrupted by the highly invasive Introduced species purple loosestrife.[28]

Climate

New Brunswick's climate is more severe than that of the other Maritime provinces, which are lower and have more shoreline along the moderating sea. New Brunswick has a humid continental climate, with slightly milder winters on the Gulf of St. Lawrence coastline. Elevated parts of the far north of the province have a subarctic climate.

Fredericton 1981–2010

Below is data for Fredericton from 1981 to 2010. The climate is similar across the province, although places near the coast are slightly cooler in July (Saint John's maximum 22 °C to Fredericton's 25 °C) and milder in January (Saint John's maximum −2 °C to Fredericton's −4 °C).

On average Fredericton gets 130 frost-free days from 18 May to 24 September.[29]

| Climate data for Fredericton 1981 to 2010 Canadian Climate Normals station data | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.8 (25.2) |

−2 (28) |

3.0 (37.4) |

10.0 (50) |

17.6 (63.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.0 (68) |

13.2 (55.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

11.4 (52.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −9.4 (15.1) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

11.1 (52) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

5.6 (42) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −15 (5) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

−7.8 (18) |

−1 (30) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−3 (27) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 95.3 (3.752) |

73.1 (2.878) |

93.2 (3.669) |

85.9 (3.382) |

96.2 (3.787) |

82.4 (3.244) |

88.3 (3.476) |

85.6 (3.37) |

87.5 (3.445) |

89.1 (3.508) |

106.3 (4.185) |

94.9 (3.736) |

1,077.8 (42.432) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 69.9 (27.52) |

47.5 (18.7) |

49.4 (19.45) |

18.6 (7.32) |

1.4 (0.55) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.8 (0.31) |

14.3 (5.63) |

50.5 (19.88) |

252.4 (99.36) |

| Source: Environment and Natural Resources Canada | |||||||||||||

Climate change

Evidence of climate change in New Brunswick includes: more intense precipitation events, more frequent winter thaws, and one quarter to half the amount of snowpack.[30]

Today the sea level is about 30 cm higher than it was 100 years ago, and is expected to rise twice that much again by the year 2100.[30]

Geology

Bedrock types range from 1 billion to 200 million years old.[31] Much of the bedrock in the west and north derives from ocean deposits in the Ordovician, which were then subject to folding and igneous intrusion, and were eventually covered with lava during the Paleozoic, peaking during the Acadian orogeny.[11]

During the Carboniferous era, about 340 million years ago, New Brunswick was in the Maritimes Basin, a sedimentary basin near the equator. Sediments, brought by rivers from surrounding highlands, accumulated there and after being compressed, producing the Albert oil shales of southern New Brunswick. Eventually sea water from the Panthalassic Ocean invaded the basin, forming the Windsor Sea. Once this receded, conglomerates, sandstones, and shales accumulated. The rust colour of these was caused by the oxidation of iron in the beds between wet and dry periods.[32] Such late carboniferous rock formed the Hopewell Rocks, which have been shaped by the extreme tidal range of the Bay of Fundy.

In the early Triassic, as Pangea drifted north it was rent apart, forming the rift valley that is the Bay of Fundy. Magma pushed up through the cracks, forming basalt columns on Grand Manan.[33]

People

The four Atlantic Provinces are Canada's least populated, with New Brunswick is the third least populous at 747,101 in 2016. The Atlantic provinces also have higher rural populations. New Brunswick was largely rural until 1951 since when the rural urban split has been roughly even.[34] Population density in the Maritimes is above average among Canadian provinces, which reflects their small size and the fact that they do not possess large unpopulated hinterlands, as do the other seven provinces and three territories.

New Brunswick's 107 municipalities[35] cover 8.6% of the province's land mass but are home to 65.3% of its population. The three major urban areas are in the south of the province and are:

- Greater Moncton, population 126,424. New Brunswick's largest city. Moncton's economy is based on the transportation, distribution, retail and commercial sectors, with strengths in insurance, healthcare and education. The Université de Moncton is the provincial francophone university.

- Greater Saint John, population 122,389. One of the busiest shipping ports in Canada in terms of gross tonnage. It is the home of Canada's biggest oil refinery, a liquefied natural gas terminal, a dry-dock, Moosehead, Canada's oldest independent brewery, and the headquarters of Irving Oil.

- Greater Fredericton (the provincial capital) population 85,688. The economy of Fredericton is tied to the governmental, military, and university sectors.

Ethnicity and language

In the 2001 census, the most commonly reported ethnicities were British and Irish 60%, French Canadian or Acadian 31%, other European 7%, First Nations 3%, Asian Canadian 2%. Each person could choose more than one ethnicity.[36]

According to the Canadian Constitution, both English and French are the official languages of New Brunswick,[37] making it the only officially bilingual province. Anglophone New Brunswickers make up roughly two-thirds of the population, with about one-third being Francophone. Recently there has been growth in the numbers of people reporting themselves as bilingual, with 34% reporting that they speak both English and French. This reflects a trend across Canada.[38]

Religion

In the 2011 census, 84% of provincial residents reported themselves as Christian:[11] 52% were Roman Catholic, 8% Baptist, 8% United Church of Canada, and 7% Anglican. Fifteen percent of residents reported no religion.

Economy

As of October 2017 seasonally-adjusted employment is 73,400 for the goods-producing sector, and 280,900 for the services-producing sector.[39]

Those in the goods producing industries are mostly employed in manufacturing or construction, while those in services work in social assistance, trades, and health care.

The US is the province's largest export market, accounting for 92% of a foreign trade valued in 2014 at almost $13 billion, with refined petroleum making up 63% of that, followed by seafood products, pulp, paper and sawmill products and non-metallic minerals (chiefly potash).

Agriculture

More than 13,000 New Brunswickers work in agriculture, shipping products worth over $1 billion, half of which is from crops, and half of that from potatoes, mostly in the Saint John River valley. McCain Foods is one of the world's largest manufacturers of frozen potato products. Other products include apples, cranberries, and maple syrup.[40] New Brunswick was in 2015 the biggest producer of wild blueberries in Canada.[41]

The value of the livestock sector is about a quarter of a billion dollars, nearly half of which is dairy. Other sectors include poultry, fur, and goats, sheep, and pigs.

Fisheries

The value of exports, mostly to the United States, was $1.6 billion in 2016. About half of that came from lobster. Other products include salmon, crab, and herring.[42]

Forestry

About 83% of New Brunswick is forested. Historically important, it accounted for more than 80% of exports in the mid 1800s. By the end of the 1800s the industry, and shipbuilding, were declining due to external economic factors. The 1920s saw the development of a pulp and paper industry. In the mid-1960s, forestry practices changed from the controlled harvests of a commodity to the cultivation of the forests.[21]

The industry employs nearly 12,000, generating revenues around $437 million.[11]

Mining

Mining was historically unimportant in the province, but since the 1950s has grown and in 2012 was an estimated $1.1 billion. Mines in New Brunswick produce lead, zinc, copper, and potash.

Tourism

In 2015, spending on non-resident tourism in New Brunswick was $441 million, which provided $87 million in tax revenue.[43]

Infrastructure

The Department of Transportation and Infrastructure maintains government facilities and the province's highway network and ferries. The Trans-Canada Highway is not under federal jurisdiction, and traverses the province from Edmundston following the Saint John River Valley, through Fredericton, Moncton, and on to Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Rail

Via Rail's Ocean service, which connects Montreal to Halifax, is currently the oldest continuously operated passenger route in North America, with stops from west to east at Campbellton, Charlo, Jacquet River, Petit Rocher, Bathurst, Miramichi, Rogersville, Moncton, and Sackville.

Canadian National Railway operates freight services along the same route, as well as a subdivision from Moncton to Sain John.

The New Brunswick Southern Railway, a division of J. D. Irving Limited, together with its sister company Eastern Maine Railway form a continuous 305 km (190 mi) main line connecting Saint John and Brownville Junction, Maine.

Energy

Energy Capacity by source in NB

Publicly-owned NB Power operates 13 of New Brunswick's generating stations, deriving power from fuel oil and diesel (1497 MW), hydro (889 MW), nuclear (660 MW), and coal (467 MW). There were 30 active natural gas production sites in 2012.[11]

Government

Under Canadian federalism, power is divided between federal and provincial governments. Among areas under federal jurisdiction are citizenship, foreign affairs, national defence, fisheries, criminal law, Indian policies, and many others. Provincial jurisdiction covers public lands, health, education, and local government, among other things. Jurisdiction is shared for immigration, pensions, agriculture, and welfare.[44]

The parliamentary system of government is modelled on the British Westminster system. Forty-nine representatives, nearly always members of political parties, are elected to the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick. The head of government is the Premier of New Brunswick, normally the leader of the party or coalition with the most seats in the legislative assembly. Governance is handled by the executive council (cabinet), with about 32 ministries.[45]

Ceremonial duties of the Monarchy in New Brunswick are mostly carried out by the Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick.

Under amendments to the province's Legislative Assembly Act in 2007, a provincial election is held every four years. The two largest political parties are the New Brunswick Liberal Association and the Progressive Conservative Party of New Brunswick. Since the 2018 election, minor parties are the Green Party of New Brunswick and the People's Alliance of New Brunswick.

Judiciary

The Court of Appeal of New Brunswick is the highest provincial court. It hears appeals from:

- The Court of Queen's Bench of New Brunswick: has jurisdiction over family law and major criminal and civil cases, and is divided accordingly into two divisions: Family and Trial. It also hears administrative tribunals.[46]

- The Probate Court of New Brunswick: has jurisdiction over estates of deceased persons.

- The Provincial Court of New Brunswick: nearly all cases involving the criminal code start here.

The system consists of eight Judicial Districts, loosely based on the counties.[47] The Chief Justice of New Brunswick serves at the apex of this court structure.

Administrative divisions

Ninety-two per cent of the land in the province, inhabited by about 35% of the population, is under provincial administration and has no local, elected representation. The 51% of the province that is Crown land is administered by the Department of Energy and Resource Development.

Most of the province is administrated as a local service district (LSD), an unincorporated unit of local governance. As of 2017 there are 237 LSDs. Services, paid for by property taxes, include a variety of services such as fire protection, solid waste management, street lighting, and dog regulation. LSDs may elect advisory committees[48] and work with the Department of Local Government to recommend how to spend locally collected taxes.

In 2006 there were three rural communities. This is a relatively new entity, and to be created requires a population of 3,000 and a tax base of $200 million.[49]

In 2006 there were 101 municipalities.

Regional Service Commissions, which number 12, were introduced in 2013 to regulate regional planning and solid waste disposal, and provide a forum for discussion on a regional level of police and emergency services, climate change adaptation planning, and regional sport, recreational and cultural facilities. The commissions' administrative councils are populated by the mayors of each municipality or rural community within a region.[50]

Historically the province was divided into counties with elected governance, but this was abolished in 1966. These were subdivided into 152 parishes which also lost their political significance in 1966, but are still used as census subdivisions by Statistics Canada.

Provincial finances

New Brunswick has the most poorly-performing economy of any Canadian province, with a per capita income of $28,000.[51] The government has historically run at a large deficit. With about half of the population being rural, it is expensive for the government to provide education and health services, which account for 60 per cent of government expenditure. Thirty-six per cent of the provincial budget is covered by federal cash transfers.[52]

The government has frequently attempted to create employment through subsidies, which has often failed to generate long-term economic prosperity and resulted in bad debt,[52] examples of which include Bricklin, Atcon,[53] and the Marriott call centre in Fredericton.[54]

According to a 2014 study by the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies the large public debt is a very serious problem. Government revenues are shrinking because of a decline in federal transfer payments. Though expenditures are down (through government pension reform and a reduction in the number of public employees), they have increased relative to GDP,[55] necessitating further measures to reduce debt in the future.

In the 2014–15 fiscal year, provincial debt reached $12.2 billion or 37.7 per cent of nominal GDP, an increase over the $10.1 billion recorded in 2011–12.[55] The debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to reach 41.9% in 2017–18, compared to a ratio of 25% in 2007–08.[56]

Culture

Education

Public education in the province is administered by the NB Department of Education. New Brunswick has a parallel system of Anglophone and Francophone public schools. There are also secular and religious private schools in the province, such as the Moncton Flight College.

The New Brunswick Community College system has campuses in all regions of the province.

The two comprehensive provincial universities are the University of New Brunswick (Fredericton and Saint John) and the Université de Moncton (Moncton, Shippegan and Edmundston). These have extensive postgraduate programs and Law schools. Medical education programs have also been established at both the Université de Moncton and at UNBSJ in Saint John (affiliated with Université de Sherbrooke and Dalhousie University respectively). Other public funded universities include Mount Allison University in Sackville and Saint Thomas University in Fredericton. Mount Allison University is a highly regarded undergraduate university with over 50 Rhodes Scholars to its credit. There are several private universities in the province as well, the largest being Crandall University in Moncton.

Literature

Julia Catherine Beckwith born in Fredericton, was Canada's first published novelist. Charles G. D. Roberts was one of the first Canadians to achieve international fame. Antonine Maillet was the first non-European winner of France’s Prix Goncourt. Other modern writers include Alfred Bailey, Alden Nowlan, John Thompson, Douglas Lochhead, K. V. Johansen, David Adams Richards, Raymond Fraser, and France Daigle. A recent New Brunswick Lieutenant-Governor, Herménégilde Chiasson, is a poet and playwright.

The Fiddlehead, established in 1945 at UNB, is Canada’s oldest literary magazine.

Visual arts

Mount Allison University in Sackville began offering classes in 1854. The program came into its own under John A. Hammond, from 1893 to 1916. Alex Colville and Lawren Harris later studied and taught art there and both Christopher Pratt and Mary Pratt were trained at Mount Allison. The University’s art gallery – which opened in 1895 and is named for its patron, John Owens of Saint John – is Canada's oldest. Modern New Brunswick artists include landscape painter Jack Humphrey, sculptor Claude Roussel, and Miller Brittain.

Music

Music of New Brunswick includes artists such as Henry Burr, Roch Voisine, Lenny Breau, and Édith Butler. Symphony New Brunswick, based in Saint John, tours extensively in the province.

Performing arts, events, and festivals

Symphony New Brunswick based in Saint John and the Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada (based in Moncton), tours nationally and internationally. Theatre New Brunswick (based in Fredericton), tours plays around the province. Canadian playwright Norm Foster saw his early works premiere at TNB. Other live theatre troops include the Théatre populaire d'Acadie in Caraquet, and Live Bait Theatre in Sackville. The refurbished Imperial and Capitol Theatres are found in Saint John and Moncton, respectively; the more modern Playhouse is located in Fredericton.

Media

New Brunswick has four daily newspapers: the Times & Transcript, serving eastern New Brunswick, the Telegraph-Journal, based in Saint John and distributed province-wide, The Daily Gleaner, based in Fredericton, and L'Acadie Nouvelle, based in Caraquet. The three English-language dailies and the majority of the weeklies are owned and operated by Brunswick News, privately owned by J. K. Irving.

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation has Anglophone television and radio operations in Fredericton. Télévision de Radio-Canada is based in Moncton.

Historic sites

There are about 61 historic places in New Brunswick, including Fort Beauséjour, Kings Landing Historical Settlement and the Village Historique Acadien, and many New Brunswick museums.

See also

References

- ↑ Ann Gorman Condon. "Winslow Papers >> Ann Gorman Condon >> The New Province: Spem Reduxit". University of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2011 and 2006 censuses". Statcan.gc.ca. February 8, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Population by year of Canada of Canada and territories". Statistics Canada. September 26, 2014. Archived from the original on June 19, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ "The Legal Context of Canada's Official Languages". University of Ottawa. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory (2011)". Statistics Canada. November 19, 2013. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ↑ Elizabeth W. McGahan. "Saint John". Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Provincial Gross Domestic Product by Industry" (PDF). Statistics Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ↑ "New Brunswick Tourism Indicators Summary Report" (PDF). Government of New Brunswick. September 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- 1 2 "Local history". Archived from the original on June 18, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ↑ Arsenault, Bona; Alain, Pascal (January 1, 2004). Histoire des Acadiens (in French). Les Editions Fides. ISBN 9782762126136. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "New Brunswick". Historica Canada. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ Bell, David (2015). American Loyalists to New Brunswick: The ship passenger lists. Formac Publishing Company. p. 7. ISBN 9781459503991. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016.

- 1 2 "Responsible Government". Historica Canada. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "New Brunswick's provincial symbols". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "New Brunswick". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Living History". Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Confederation". Historica Canada. Archived from the original on November 26, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Reciprocity". Historica Canada. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "New Brunswick and Confederation". Historica Canada. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "New Brunswick". Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- 1 2 Forbes, Ernest R. "New Brunswick". Archived from the original on June 22, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Symbols". Service New Brunswick. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Landforms and Climate". Ecological Framework of Canada. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Burrel, Brian C; Anderson, James E (1991). "REGIONAL HYDROLOGY OF NEW BRUNSWICK". Adian Water Resources Journal /. 16 (4): 317. doi:10.4296/cwrj1604317. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ Noseworthy, Josh. "A WALK IN THE WOODS: ACADIAN OLD-GROWTH FOREST". Nature Conservancy Canada. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- 1 2 Simpson, Jamie. "Restoring the Acadian Forest" (PDF). Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ "Furbish's Lousewort". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Purple loosestrife". New Brunswick Alliance of Lake Associations. Archived from the original on November 30, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010 Station Data". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- 1 2 "How is Climate Change Affecting New Brunswick?". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Bedrock Mapping". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ↑ Atlantic Geoscience Society (2001). Williams, Graham; Fensome, Robert, eds. The last billion years : a geological history of the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Halifax, NS: Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1-55109-351-0.

- ↑ "Geology". Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Population, urban and rural, by province and territory (New Brunswick)". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Association of Municipal Administrators of New Brunswick". The Association of Municipal Administrators of New Brunswick. 2015. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Ethnic Origin (232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) (2001 Census)". 2.statcan.ca. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Official Languages Act". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ "New Brunswick bilingualism rate rises to 34%". CBC. Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Employment by major industry group, seasonally adjusted, by province (monthly) (New Brunswick)". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Crops". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ acadienouvelle.com: "La production de bleuets sauvages prend de l’expansion au Nouveau Brunswick" Archived December 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., 21 Apr 2016

- ↑ "New Brunswick agrifood and seafood export highlights 2016" (PDF). Government of New Brunswick. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Tourism contributes to economy". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Canada's Legal System – Sharing of Legislative Powers in Canada". University of Ottawa. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Members of the Executive Council". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ "New Brunswick Courts". Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ "COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH OF NEW BRUNSWICK". Archived from the original on July 13, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Local Service Districts (LSDs)". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ Beckley, Thomas M. "New Brunswick". State of Rural Canada. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ Canada, Government of New Brunswick,. "Structure of the new Regional Service Commissions". www2.gnb.ca. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017.

- ↑ "New Brunswick's 'struggling' economy ranks near bottom of report". CBC. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- 1 2 Patriquin, Martin. "Can anything save New Brunswick?". Maclean's. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Atcon was so badly managed, taxpayers' $63M was never going to save it, AG finds". CBC. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Fredericton call centre closure will cost 265 jobs". CBC. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- 1 2 Murrell, David; Fantauzzo, Shawn (2014). "New Brunswick's Debt and Deficit" (PDF). Atlantic Institute for Market Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Canadian Federal and Provincial Fiscal Tables" (PDF). Economic Reports. Royal Bank of Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Brunswick. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for New Brunswick. |

| Look up new brunswick in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

.jpg)