Regional Municipality of Waterloo

| Waterloo Region | ||

|---|---|---|

| Upper-tier regional municipality | ||

| Regional Municipality of Waterloo | ||

| ||

| Motto(s): "Peace, Prosperity!" | ||

Location of Waterloo Region in Ontario | ||

| Coordinates: 43°28′N 80°30′W / 43.467°N 80.500°WCoordinates: 43°28′N 80°30′W / 43.467°N 80.500°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| Province |

| |

| Government | ||

| • Regional Chair | Ken Seiling | |

| • Governing Body | Waterloo Regional Council | |

| • MPs |

List of MPs

| |

| • MPPs |

List of MPPs

| |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Land | 1,368.92 km2 (528.54 sq mi) | |

| Population (2016)[2] | ||

| • Total | 535,154 | |

| • Density | 390.9/km2 (1,012/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | |

| Area code(s) | (519) and (226) | |

| Website |

region | |

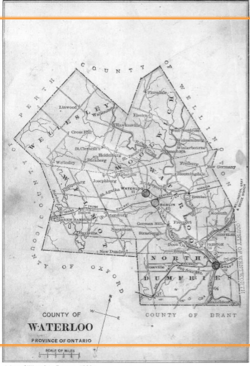

The Regional Municipality of Waterloo is a regional municipality located in Southern Ontario, Canada. It consists of the cities of Kitchener, Waterloo and Cambridge, (collectively called the Tri-Cities), and the townships of Wellesley, Woolwich, Wilmot, and North Dumfries. It is often referred to as the Region of Waterloo or Waterloo Region. The region is 1,369 square kilometres in size and its regional seat of government is in Kitchener.

The region's population was 535,154 at the 2016 census.[2] In 2016, the Kitchener, Waterloo, Cambridge area was the third best place in Canada to find full-time employment based on data from StatsCan.[3]

The region was preceded by Waterloo County, Ontario, created in 1853 and dissolved in 1973. That entity consisted of five townships: Woolwich, Wellesley, Wilmot, Waterloo, and North Dumfries, including the cities and towns in each area.

History

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the area was inhabited by the Iroquoian speaking Attawandaron nation.

Historical accounts differ on exactly how the Attawandaron tribe was wiped out, but it is generally agreed that the Seneca and the Mohawk tribes of the Six Nations destroyed or forced out the smaller Attawandaron tribe while severely crippling the Huron around 1680-85. After the invasion of the Six Nations into the Grand River Valley, the Neutral tribe ceased to have any political existence. Any dispersed survivors were taken captive or escaped to other tribes such as the Mississaugas and were assimilated into that culture. There are no distinct Attawandarons today.

In 1784, the British government granted the Grand River Valley to the Iroquois, who had supported the Loyalists in the American War of Independence, to compensate them for the loss of their land in New York.[4] The Iroquois settled in the lower Grand River Valley (now The County of Brant), and sold parts of the land which was part of Waterloo Township to Colonel Richard Beasley, a United Empire Loyalist. Another developer was William Dickson who, in 1816, came into sole possession of 90,000 acres (360 km2) of land along the Grand River that was later to make up North and South Dumfries Townships.

North and South Dumfries Townships area

William Dickson of Niagara purchased land in the township of North Dumfries and South Dumfries which would become much of what is now Cambridge, Ontario. It was Dickson's intention to divide the land into smaller lots that would be sold primarily to the Scottish settlers that he hoped to attract to Canada.[4] In the company of Absalom Shade, Dickson immediately toured his new lands with the intention of developing a town site that would serve as the focal point for his attempts to populate the countryside. They chose the site where Mill Creek flows into the Grand River and in 1816 the settlement of Shade's Mills was born. The new settlement grew slowly but by 1825, though still very small, was the largest settlement in the area and was important enough to obtain a post office.

Dickson decided that a new name was needed for the Post Office and consequently the settlement and he chose Galt in honour of the Scottish novelist and Commissioner of the Canada Company, John Galt. The settlers resisted the introduction of the new name preferring the more familiar Shade's Mills. However, after Galt visited Dickson in the settlement in 1827 the name Galt received more widespread acceptance. In its early days Galt was an agricultural community serving the needs of the farmers in the surrounding countryside. By the late 1830s, however, the settlement began to develop an industrial capacity and reputation for quality products that in later years earned the town the nickname "The Manchester of Canada". Galt was the largest and most important town in the area until the beginning of the 20th century when it was finally overtaken by Kitchener.[5]

Kitchener-Waterloo area

Settlement of the what became the Township of Waterloo and later, Waterloo County, Ontario, started in the early 1800s.

1800 to 1820

Among the first settlers, Joseph Schoerg and Samuel Betzner, Jr. (brothers-in-law), Mennonites, arrived from Franklin County, Pennsylvania. Other settlers followed mostly from Pennsylvania typically by Conestoga wagons. The early group purchased land from Richard Beasley who had acquired it from the Six Nations. The first school was begun in 1802 near the village of Blair.

Many of the pioneers immigrating from Pennsylvania after November 1803 bought land in a 60,000-acre section of Block Two from the German Company established by a group of Mennonites from Lancaster County Pennsylvania. The tract included most of Block 2 of the previous Grand River Indian Lands. Many of the first farms were least 400 acres in size.[6][7][8] The majority of the settlers before about 1830 were Mennonites from Pennsylvania, who had roots in Germany or Switzerland. They were often called Pennsylvania Dutch although they were actually Deutsch, German.[9]

Later declared the founder of the City of Waterloo, Abraham Erb, from Franklin County, Pennsylvania, bought 900 acres (360 ha) of bush land in 1806 from the German Company (later to be part of Waterloo Township). He built a sawmill in 1808 and a gristmill in 1816; the latter operated continuously for 111 years.[10] Other early settlers of what would become Waterloo included Samuel and Elia Schneider who arrived in 1816. Until about 1820, settlements such as this were quite small.[6]

In 1807, 45,195 acres (182.9 km²) of Block 3 (Woolwich) was purchased by Pennsylvanians John Erb, Jacob Erb and others.

Later named the founder of Kitchener, Benjamin Eby (made Mennonite preacher 1809, and bishop in 1812) was also from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. He arrived in 1806 and purchased a very large tract of land consisting of much of what would become the village of Berlin (named about 1830). The settlement was initially called Ebytown and was at the south-east side of what would later become Queen Street. (Eby was also responsible for the growth of the Mennonite church in Waterloo County; he built the first church in 1813.) Abram Weber settled on the corner of what would become King and Wilmot Streets and David Weber in the area of the much later Grand Trunk Railway station.[6][10] Benjamin Eby encouraged manufacturers to move to the village. Jacob Hoffman came in 1829 or 1830 and started the first furniture factory.

Almost as important as Benjamin Eby in the history of Kitchener, Joseph Schneider of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (son of immigrants from southern Germany) bought lot 17 of the German Company Tract of block 2 in 1806. While farming, he helped to build what became "Schneider's Road" and by 1816 built a sawmill. Years later, Schneider and Phineas Varnum would help form the commercial centre of Ebytown.[11]

The War of 1812 interrupted settlement. The Mennonite settlers refused to carry arms so were employed in camps and hospital and as teamsters in transport service during the war.

1820 to 1852

John Eby, druggist and chemist, arrived from Pennsylvania in about 1820 and opened a shop to the west of what would later be Eby Street. At the time, it was common for settlers to form a building "bee" to help newcomers erect a long home.[6] Immigration from Lancaster county continued heavily in the 1820s because of a severe agricultural depression in Lancaster County.[9] Joseph Schneider, from that area, built a frame house in 1820 on the south side of the future Queen Street after clearing a farm and creating a rough road; a small settlement formed around "Schneider's Road" which became the nucleus of Berlin. The home was renovated over a century later and still stands.[10]

The village centre of what would become Berlin (Kitchener) was established in 1830 by Phineas Varnum who leased land from Joseph Schneider and opened a blacksmith shop on the site where a hotel would be built many years later, the Walper House. A tavern was also established here at the same time and a store was opened.[6] At the time, the settlement of Berlin was still considered to be a hamlet.[7]

By 1830 the village of Preston was a thriving business centre with Jacob Hespeler, a native of Württemberg and a prominent citizen. He would later move to the village of New Hope that was renamed Hespeler in 1857 in recognition of his public service and the industries he started there. Jacob Beck from the Grand Duchy of Baden founded the village of Baden in Wilmot Township and started a foundry and machine shop. Jacob Beck was the father of Sir Adam Beck.

.jpg)

Many of the Mennonite places of worship (meeting houses) were basic frame buildings and this type is still common among Old Order Mennonite groups in the rural areas of Waterloo Region.[12]

By 1835, many immigrants to Waterloo County were not from Pennsylvania. Many settler came from German, and also from England, Ireland and Scotland. The immigrants from Germany settled in areas such as New Germany in the Lower Block of Block Two. In 1835, approximately 70% of the population was Mennonite but by 1851, only 26% of the much larger population were of this religion.[9]

The first newspaper of the county (first issue dated August 27, 1835) was the Canada Museum und Allgemeine Zeitung, printed mostly in German and partly in English. It was published for only five years.[13]

By the 1840s, the presence of the German-speaking Mennonites made the area a popular choice for German settlers from Europe.[14] These Germans founded their own communities in the south of the area settled by the Mennonites, the largest being the town of Berlin (changed to Kitchener, named for Lord Kitchener, due to anti-German sentiments during World War I).

The Smith's Canadian Gazetteer of 1846 states that the Township of Waterloo (smaller than Waterloo County) consisted primarily of Pennsylvanian Mennonites and immigrants directly from Germany who had brought money with them. At the time, many did not speak English. There were eight grist and twenty saw mills in the township. In 1841, the population count was 4424. In 1846 the village of Waterloo had a population of 200, "mostly Germans". There was a grist mill and a sawmill and some tradesmen.[15] Berlin (Kitchener) had a population of about 400, also "mostly German", and more tradesmen than the village of Waterloo."[16]

After 1852

Previously part of the United County of Waterloo, Wellington and Grey, Waterloo became a separate entity in 1853, with its five townships. There had been some contentious debate between Galt and Berlin (later, Kitchener) as to where the county seat would be located; one of the requirements for founding was the construction of a courthouse and jail. When local merchant Joseph Gaukel donated a small parcel of land he owned (at the current Queen and Weber streets), this sealed the deal for Berlin which was still a small community. The courthouse at the corner of the later Queen Street North and Weber Street and the gaol were built within a few months. The first County council meeting was held in the new facility on 24 January 1853, as the county officially began operations.[17][18] Both are on Canadian Register of Historic Places.[19][20]

The new County Council included 12 members from the five townships and two villages; Dr. John Scott was appointed as the first warden (reeve). In the following years, various county institutions and facilities would be created, including roads and bridges, schools, a House of Industry and Refuge, agricultural societies and local markets.[21]

The railway (Grand Trunk) reached Berlin in 1856 and that accelerated the growth of industry. In the next decade factories and the homes of labourers and wealthy owners replaced the early settlers log houses.[7]

House of Industry and Refuge

In 1869, the county built a very large so-called Poorhouse with an attached farm, the House of Industry and Refuge that accommodated some 3,200 people before being closed down in 1951; the building was subsequently demolished. It was located on Frederick St. in Kitchener, behind the now Frederick Street Mall and was intended to minimize the number of people begging, living on the streets or being incarcerated at a time before social welfare programmes became available. A 2009 report by the Toronto Star explains that "pauperism was considered a moral failing that could be erased through order and hard work".[22]

Electric streetcar

A new streetcar system, the Galt, Preston and Hespeler electric railway (later called the Grand River Railway) began to operate in 1894 connecting Preston and Galt. In 1911, the line reached Hespeler, Kitchener (then called Berlin) and Waterloo; by 1916 it had been extended to Brantford/Port Dover.[23][24] The electric rail system ended passenger services in April, 1955.

Germanic heritage

Some sources estimate that roughly 50,000 Germans directly from Europe settled in and around Waterloo County, between the 1830s and 1850s.[25] Unlike the predominantly Mennonite German-speaking settlers from Pennsylvania – most of whom had arrived earlier – the majority of those from Germany (including Austria and other parts of Germany which are now a part of other countries, such as Poland, France or Russia) were of other denominations. The first groups were predominantly Roman Catholic and the majority of those who arrived later were primarily Lutheran.[26]

In 1862, German-speaking groups held the Sängerfest, or "Singer Festival" concert event that attracted an estimated 10,000 people and continued for several years.[27]

Eleven years later, the more than 2000 Germans in Berlin, Ontario, started a new event, Friedenfest, commemorating the German victory in the Franco-Prussian war. This annual celebration continued until the start of World War I.[28]

By 1871, nearly 55 percent of the population had German origins, including the Pennsylvania Mennonites and European Germans. This group greatly outnumbered the Scots (18 per cent), the English (12.6 per cent) and the Irish (8 per cent).[26] Berlin, Ontario was a bilingual town, with German being the dominant language spoken. More than one visitor commented on the necessity of speaking German in Berlin.

In 1897, the Canadians with origins in Germany raised funds to erect a large monument, with a bronze bust of Kaiser Wilhelm I, in Victoria Park. The monument would be destroyed by townspeople just after the start of World War I.[29]

By the early 1900s, northern Waterloo County – the Kitchener, Waterloo, Elmira area – exhibited a strong German culture and those of German origin made up a third of the population in 1911. Lutherans were the primary religious group. There were nearly three times as many Lutherans as Mennonites at that time. The latter primarily resided in the rural areas and small communities.[30]

Before and during World War I, there was some anti-German sentiment in Canada and some cultural sanctions on the community, particularly in Berlin, Ontario. However, by 1919 most of the population of what would become Kitchener-Waterloo and Elmira were Canadian by birth; over 95 percent had been born in Ontario.[31] Those of the Mennonite religion were pacifist, so they could not enlist, while others who were not born in Canada refused to fight against the country of their birth.[32][33] The anti-German sentiment was the primary reason for the Berlin to Kitchener name change in 1916.[34]

The Waterloo Pioneer Memorial Tower built in 1926 commemorates the settlement by the Pennsylvania Dutch (Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch or Pennsylvania German) of the Grand River area in what later became Waterloo County.[35]

The region is still home to the largest population of Old Order Mennonites in Canada, particularly in the areas around St Jacobs and Elmira.[36]

The Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest event, with beer halls and German entertainment, and a large parade, is a remembrance of its German heritage, attracting an average of 700,000 people to the county. During the 2016 Oktoberfest parade, an estimated 150,000 people lined the streets along the route.[37][37]

Restructuring

The Waterloo region remained predominantly German-speaking until the early 20th century, and its German heritage is reflected in the region's large Lutheran community and the annual Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest.

There are still traditional Mennonite communities located north of Kitchener-Waterloo. While the best known is St. Jacobs, with its very popular thrice-weekly outdoor market, the community of Linwood has attracted increased tourist volume in recent years due to its highly authentic Mennonite lifestyle.

In 1973, the regional municipality style of government was imposed on the county. The cities of Galt, Kitchener, and Waterloo were previously independent single tier municipalities prior to joining the newly formed regional municipality. In that major reorganization, the fifteen towns and townships of the county were reduced to just seven in the new Region of Waterloo. The new city of Cambridge was created through the amalgamation of the City of Galt, the towns of Preston and Hespeler, the Village of Blair, and various parcels of township land. One township vanished when the former Waterloo Township was divided among Woolwich Township and the three cities of Kitchener, Waterloo, and Cambridge. The settlement of Bridgeport was annexed to the city of Kitchener. The settlement of Erbsville was annexed to the city of Waterloo. The former county government was given broader powers as a regional municipality.

Further municipal amalgamation began discussions in the 1990s, with little progress. In late 2005, Kitchener's city council voted to visit the subject again, with the possibility of reducing the seven constituent municipalities into one or more cities. A new proposal in 2010 would study only the merger of Kitchener and Waterloo, with a public referendum on whether the idea should be looked into. Kitchener residents voted 2-1 in favour of studying the merger while Waterloo residents voted 2-1 against. Waterloo city council voted against the study.[38]

Regardless of the resistance, the amalgamation proceeded and became effective 1 January 1973, creating the Region of Waterloo, with Jack A. Young as the first chairman. The region took over many services, including police, waste management, recreation, planning, roads and social services.[39]

Government

The region's governing body is the 16 member Waterloo Regional Council. The council consists of the Regional Chair, the mayors of the seven cities and townships, and eight additional councillors – four from Kitchener and two each from Cambridge and Waterloo.

Prior to 1997, the Regional Chair was appointed by the councillors, who were elected by the citizens of Waterloo Region. Since the 1997 election, the citizens of Waterloo Region have directly elected the Chair. Of the nine regional municipalities in Ontario, Waterloo Region and the Regional Municipality of Halton are the only ones that allow for direct election of the chair.

Ken Seiling has held the position of Regional Chair since 1985.[40]

Communities

| Census Subdivision | Population (2016 census)[41] |

|---|---|

| City of Kitchener | 233,222 |

| City of Cambridge | 129,920 |

| City of Waterloo | 104,986 |

| Township of Woolwich | 25,006 |

| Township of Wilmot | 20,545 |

| Township of Wellesley | 11,260 |

| Township of North Dumfries | 10,215 |

Within the townships are many communities. Some were once independent and had their own reeves and councils but lost this status in amalgamation. These communities include: Ayr, Baden, Bloomingdale, Breslau, Conestogo, Doon, Elmira, Freeport, Heidelberg, Mannheim, Maryhill, New Dundee, New Hamburg, Petersberg, Roseville, St. Agatha, St. Clements, St. Jacobs, Wellesley, West Montrose, and Winterbourne.

The Kitchener-Waterloo area, including New Hamburg and other small towns, is among the best places to retire in Ontario, according to Comfort Life, a publication for seniors.[42]

Demographics

| Canada census – Regional Municipality of Waterloo community profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2006 | ||

| Population: | 507,096 (6.1% from 2006) | 478,121 (9.0% from 2001) | |

| Land area: | 1,368.94 km2 (528.55 sq mi) | 1,368.64 km2 (528.43 sq mi) | |

| Population density: | 370.4/km2 (959/sq mi) | 349.3/km2 (905/sq mi) | |

| Median age: | 36.4 (M: 35.5, F: 37.4) | ||

| Total private dwellings: | 202,121 | 187,088 | |

| Median household income: | |||

| References: 2011[43] 2006[44] earlier[45] | |||

Historic populations:[45]

- Population in 2001: 438,515

- Population in 1996: 405,435

Waterloo is one of the fastest growing regions in Southwestern Ontario; by 2031, the region's population is expected to grow to 729,000,[46] This, among other factors, has made new residential construction rates very high; concerns about urban sprawl, with all its effects, continue to be raised.

The population is increasingly diverse owing to its proximity to the Greater Toronto Area as well as its status as a technology hub. Immigrants accounted for 22.3% of the region's total population according to the 2006 census.[47] According to the 2011 National Household Survey, visible minorities accounted for 15.4% of the region's total population.

Education

Waterloo Region is home to the University of Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University, and Conestoga College. For a list of all elementary and secondary schools in the area, see the List of Waterloo Region, Ontario schools.

Crime rate

The national average for the crime severity index was 70.96 per 100,000 people in 2016, according to a study published by Macleans while the rate was much lower for Waterloo Region: 61 per 100,000 people. By comparison, the rate for nearby Guelph (population 132, 350)[48] was 55 per 100,000 people. By comparison, "Canada's most dangerous place", North Battleford, Saskatchewan, had an index of 353.[49]

Business

Waterloo Region is also experiencing significant commercial growth. The presence of two universities, the University of Waterloo and Wilfrid Laurier University, acts as a catalyst for high-tech growth and innovation. The region is known for its high concentration of tech companies, such as BlackBerry (formerly Research In Motion), OpenText, Kik, and Maplesoft. As such, it has often been referred to as "Canada's Silicon Valley".[50][51]

According to economist Mike Moffatt, an assistant professor at Western's Ivey Business School, "the Kitchener-Waterloo economy is one of the fastest growing in the province".[52]

Major employers in the region

- Waterloo Region District School Board (5,000 employees)[53]

- Toyota Motor Manufacturing Canada (6,500 employees)

- Manulife Financial (3,800 employees)

- University of Waterloo (3,500 employees)

- Sun Life Financial (3,300 employees)

- BlackBerry Ltd (3,000 employees[54])

- Grand River Hospital (2,200 employees)

- ATS Automation Tooling Systems (1,800 employees)

- City of Kitchener (1,700 employees)

Services

Over time, many services have come to be delegated to the jurisdiction of the municipal government. These include police, emergency medical services, waste management, licensing enforcement, recycling, and the public transit system. The main administration of these services is run from Kitchener, however many service offices may be found in different parts of the Region. For example, from a geographically central location in north Cambridge, maintenance operations and the police headquarters are able to manage operations and provide services to the entire service area.

Transportation

Public transportation is provided by Grand River Transit, which is an amalgamation of the former Cambridge Transit and Kitchener Transit systems.

In June 2011, regional council approved the plan for a light rail transit (LRT) line from Conestoga Mall in north Waterloo to Fairview Park Mall in south Kitchener, with rapid buses through to Cambridge.[55] In Stage 1, to start operating in 2018, the Ion rapid transit system will run between Waterloo and Kitchener, passing through the downtown/uptown areas. Most of the rails had been installed by late 2016.

Until light rail transit is extended to the downtown Galt area of Cambridge from Kitchener in Stage 2, the rapid transit will use adapted iXpress buses between Fairview Park Mall and the Ainslie Street Transit Terminal. Other stops for this Ion bus are at Hespeler Road at the Delta, Can-Amera, Cambridge Centre, Pinebush, and Sportsworld. The rapid transit bus uses bus-only lanes at Pinebush, Munch and Coronation to minimize slowdowns at times of heavy traffic. After the LRT train has started operating in Kitchener-Waterloo, the ION bus will provide a link to that system.[56][57]

Construction on the light rail system began in August 2014, and the Stage 1 service was expected to begin in late 2017.[58] In 2016 however, the start date was changed to early 2018 because of delays in the manufacture and delivery of the vehicles by Bombardier Transportation. As of late March 2017 a single sample-only train car had arrived.[59]

In late February 2017, plans for the Stage 2 (Cambridge section) of the Ion rail service were still in the very early stage; public consultations were just getting started at the time. Some routes and stops had been agreed upon in 2011, but the final plan will not be established until mid 2017.[60][61] (At least one journalist has pointed out the similarity between this plan and the electric Grand River Railway of the early 1900s.)[62]

Waterloo Region was the home of the first carsharing organization in Ontario in 1998. Community CarShare Cooperative (previously known as Grand River CarShare) provides access to vehicles on a self-serve, pay-per-use basis, and which are located in many neighbourhoods around the Region. It is meant to complement other sustainable modes of transportation such as public transit, biking, carpooling, or act as a transition out of owning a vehicle. Community CarShare has 27 vehicles stationed in the Region of Waterloo.

The region also owns and operates the Region of Waterloo International Airport, near Breslau. The airport is the 20th busiest in Canada as of December 2010[63] and underwent a major expansion in 2003. GO Transit and Via Rail provide rail services to the region on the Kitchener line.

Media

Notable residents

- NHL player Mike Hoffman, who wears number 68 for the Ottawa Senators is from Kitchener, Ontario.

- Rich Beddoe is the drummer for the Canadian rock band Finger Eleven. He is from Cambridge, Ontario.

- Hockey player Todd Bertuzzi of the Detroit Red Wings makes his offseason home in Kitchener.

- Tim Brent is a hockey player from Cambridge, Ontario.

- Amanda Burk, artist who grew up in Kitchener-Waterloo.

- Author David Chilton, who wrote the best-selling Canadian book to date, financial planning guide The Wealthy Barber, was born in Kitchener and lives in the region.

- Author and journalist Malcolm Gladwell grew up in Elmira, Ontario.

- David Johnston, former President of the University of Waterloo and Governor General of Canada lives in Wellesley Township.

- William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canada's longest serving prime minister, was born in Kitchener's predecessor Berlin, Ontario. His boyhood home is now Woodside National Historic Site.

- Mike Lazaridis, founder of Research In Motion, came as a student to attend the University of Waterloo.

- Boxer Lennox Lewis lived in Kitchener from the age of 12 and began his boxing career there. He maintains a home in Kitchener.

- Lois Maxwell, Golden Globe winning actress and the original Miss Moneypenny in the James Bond movies, was born in Kitchener.

- Actor David Orth, of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World, grew up in Kitchener.

- Actor Jeremy Ratchford from Cold Case grew up in Kitchener.

- Joseph E. Seagram was a partner in 1869, and sole owner in 1883, in the company later known as Seagram.

- Donald Shaver created a world leading poultry breeding business.

- Dave Sim, creator of the comic book Cerebus the Aardvark, has lived in Kitchener since he was two years old.

- Edna Staebler, author and literary journalist, best known for her series of cookbooks, particularly Food That Really Schmecks

- Former hockey all-star Scott Stevens of the New Jersey Devils was born in Kitchener and played for the Kitchener Rangers. He also maintains a home there.

- Artist Homer Watson, internationally renowned landscape artist, was born in the village of Doon (now part of Kitchener).

See also

References

- "Economic Profile". Doing Business in the Region of Waterloo. Regional Municipality of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 2006-08-20. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

Notes

- ↑ "(Code 3530) Census Profile". 2011 census. Statistics Canada. 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- 1 2 Outhit, Jeff (8 February 2017). "Waterloo Region growing but not as fast, census shows". Record. Kitchener. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ "Canada's best cities for full-time jobs". globalnews.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Regional History - History of Waterloo County". Region of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 2011-06-03. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ "City Archives Historical Information-Evolution of Galt".

- 1 2 3 4 5 "History" (PDF). Waterloo Historical Society 1930 Annual Meeting. Waterloo Historical Society. 1930. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Kitchener-Waterloo Ontario History - To Confederation".

- ↑ "Waterloo Township". Waterloo Region Museum Research. Region of Waterloo. 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

To correct the situation, a formal agreement was arranged between Brant and Beasley. This arrangement allowed Beasley to sell the bulk of Block Two in order to cover his mortgage obligations completely, while giving the Mennonite buyers legal title to land they had previously purchased. Beasley sold a 60,000 acre tract of land to the German Company of Pennsylvania represented by Daniel Erb and Samuel Bricker in November 1803. Beasley's sale to the German Company not only cleared him of a mortgage debt, but left him with 10,000 acres of Block Two land which he continued to sell into the 1830s.

- 1 2 3 "Waterloo Township". Waterloo Region Museum Research. Region of Waterloo. 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Historical Plaques of Waterloo County". Archived from the original on 2017-03-12.

- ↑ "Biography – SCHNEIDER, JOSEPH – Volume VII (1836-1850) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography".

- ↑ "Mennonites - An Insider's Guide to Waterloo Region - Page 2".

- ↑ Breithaupt, William Henry (1927). "History of Waterloo County". In Middleton, Jesse Edgar; Landon, Fred. Province of Ontario – A History 1615 to 1927. Toronto: Dominion Publishing Company. p. 991.

- ↑ "Historic Place Names of Waterloo County - Waterloo Township". Region of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 2011-01-20. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ Smith, Wm. H. (1846). SMITH'S CANADIAN GAZETTEER - STATISTICAL AND GENERAL INFORMATION RESPECTING ALL PARTS OF THE UPPER PROVINCE, OR CANADA WEST:. Toronto: H. & W. ROWSELL. pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Smith, Wm. H. (1846). SMITH'S CANADIAN GAZETTEER - STATISTICAL AND GENERAL INFORMATION RESPECTING ALL PARTS OF THE UPPER PROVINCE, OR CANADA WEST:. Toronto: H. & W. ROWSELL. p. 15.

- ↑ mills, rych (14 July 2017). "Flash from the Past: Seven meetings that decided Waterloo County". therecord.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Waterloo County Jail and Governor's House". Canada's Historic Places. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Waterloo County Jail and Governor's House". Historic Places. Parks Canada. 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "Discovering the Region" (PDF). Doors Open, Region of Waterloo. Region of Waterloo. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "Waterloo County, Plaque 36". Historical Plaques of Waterloo County. Wayne Cook. 2011. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ Tyler, Tracey (January 3, 2009). "When 'poorhouse' wasn't only an expression". Toronto Star. Toronto. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ↑ "CAMBRIDGE AND ITS INFLUENCE ON WATERLOO REGION'S LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT". Waterloo Region. Waterloo Region. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ↑ Mills, Rych (10 January 2017). "Flash From the Past: Preston Car and Coach goes up in smoke". Record. Kitchener. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ↑ "German Canadians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Full text of "Waterloo County to 1972 : an annotated bibliography of regional history"".

- ↑ "Waterloo Region 1911". Waterloo Region WWI. University of Waterloo. 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ "Friedensfest (1871)". Waterloo Region WWI. University of Waterloo. 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ "Waterloo County, Plaque 24". Historical Plaques of Waterloo County. Wayne Cook. 2011. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "Waterloo Region Pre-1914". Waterloo Region WWI. University of Waterloo. 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ "Waterloo Region 1911". Waterloo Region WWI. University of Waterloo. 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ "Mennonites and conscription - Wartime Canada".

- ↑ D'Amato, Louisa (28 June 2014). "First World War ripped away Canada's 'age of innocence'". Kitchener Post, Waterloo Region Record. Kitchener. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ↑ "Kitchener mayor notes 100th year of name change".

- ↑ "HistoricPlaces.ca - HistoricPlaces.ca".

- ↑ "Old Order Mennonites". wordpress.com. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- 1 2 Baker, Jennifer K. (16 October 2016). "Oktoberfest 2016 comes to a close". ctvnews.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Kitchener meets its Waterloo". 28 July 2011.

- ↑ "Get to Know Us During Local Government Week". Waterloo Region. Waterloo Region. 10 October 2012. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ "Meet Ken Seiling". Region of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ↑ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2017-10-30.

- ↑ "Best places to retire in Ontario". www.comfortlife.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "2011 Community Profiles". Canada 2011 Census. Statistics Canada. July 5, 2013. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- ↑ "2006 Community Profiles". Canada 2006 Census. Statistics Canada. March 30, 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- 1 2 "2001 Community Profiles". Canada 2001 Census. Statistics Canada. February 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Living in the Region of Waterloo". waterloo.on.ca. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Region of Waterloo Census Bulletin" (PDF). Region of Waterloo. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ "Latest crime stats show Guelph is losing ground as one of Canada's safest places to live". guelphmercury.com. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Canada's Most Dangerous Places 2018: Explore the data". macleans.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Canada's Silicon Valley". Bay Street Bull. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Henry, Zoë (2 November 2015). "Why Waterloo, Ontario, Is the Silicon Valley of Canada". Inc.

- ↑ Jones, Allison (February 8, 2017). "Canada Census 2016: Ontario growth still slowing, but those who went West might soon be back". National Post. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Profitworks.ca Blog Post - Largest Employers in Waterloo and Kitchener".

A list of the top 20 employers in Waterloo Region. Ranking and figures are for the number of employment positions each company has located in Waterloo Region, not global employment numbers

- ↑ "25,500 in region are out of work; Downturn feels familiar".

Research In Motion's local workforce has grown to more than 8,000 from 450 in early 2000

- ↑ "Rail plan passes". TheRecord. 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "RAPID TRANSIT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PHASE 2, STEP 3b – PREFERRED RAPID TRANSIT SYSTEM OPTION AND STAGING PLAN" (PDF). Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ↑ "ION Bus Rapid Transit - Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Waterloo Region's Rapid Transit System to Shape Growth, Development". Metro Magazine. October 13, 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ Flanagan, Ryan (24 February 2017). "Bombardier '100% committed' to delivering Ion vehicles by end of 2017". CTV News. Bell Media. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Sharkey, Jackie (8 February 2017). "There's still wiggle room in the Region of Waterloo's LRT plans for Cambridge". CBC. CBC. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ↑ Sharkey, Jackie (February 2017). "Stage 2 ION: Light Rail Transit (LRT)" (PDF). Region of Waterloo. Region of Waterloo. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Cambridge and its Influence on Waterloo Region's Light Rail Transit". Waterloo Region. Waterloo Region. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

the first electric line running up Water and King Streets from Galt to the Mineral Springs Hotel across the Speed River in Preston ... Next, the train line extended north of Kitchener and a spur line ran into Hespeler.

- ↑ "Total aircraft movements by class of operation". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Regional Municipality of Waterloo. |