Toronto streetcar system

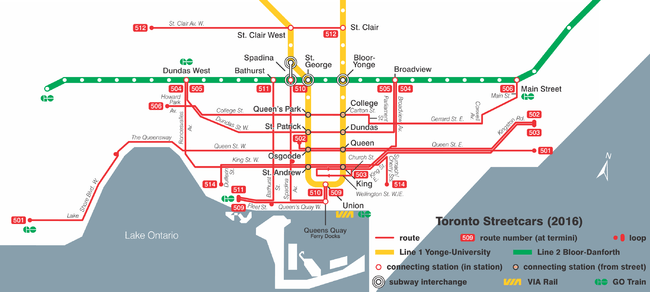

Toronto streetcar in 2016 | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locale | Toronto, Ontario, Canada | ||

| Transit type | Streetcar | ||

| Number of lines | 10[1] | ||

| Number of stations | 685 stops[2] | ||

| Daily ridership |

292,100 (avg. weekday, Q4 2016)[3] | ||

| Annual ridership | 95,761,000 (2016)[4] | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 1861 (electric lines since 1892)[1] | ||

| Operator(s) | Toronto Transit Commission | ||

| Character | Street running | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 83 km (52 mi)[5] | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 10 7⁄8 in (1,495 mm) Toronto gauge | ||

| Minimum radius of curvature | 36 ft 0 in (10,973 mm)[6] | ||

| Electrification | Trolley wire, 600 V DC | ||

| |||

The Toronto streetcar system is a network of eleven streetcar routes in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, operated by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). It is second busiest light-rail system in North America. The network is concentrated primarily in Downtown Toronto and in proximity to the city's waterfront. Much of the streetcar route network dates from the 19th century. Most of Toronto's streetcar routes operate on street trackage shared with vehicular traffic, and streetcars stop on demand at frequent stops like buses.

Toronto's streetcars provide most of the downtown core's surface transit service. Four of the TTC's five most heavily used surface routes are streetcar routes. In 2016, ridership on the streetcar system totalled more than 95 million.[4]

History

Early history (1861–1945)

In 1861, the City of Toronto issued a thirty-year transit franchise (Resolution 14, By-law 353) for a horse-drawn street railway, after the Williams Omnibus Bus Line had become heavily loaded. Alexander Easton's Toronto Street Railway (TSR) opened the first street railway line in Canada on September 11, 1861, operating from Yorkville Town Hall to the St. Lawrence Market. At the end of the TSR franchise, the City government ran the railway for eight months, but ended up granting a new thirty-year franchise to the Toronto Railway Company (TRC) in 1891. The TRC was the first operator of horseless streetcars in Toronto. The first electric car ran on August 15, 1892, and the last horse car ran on August 31, 1894, to meet franchise requirements.

There came to be problems with interpretation of the franchise terms for the City. By 1912, the city limits had extended significantly, with the annexation of communities to the north (1912: North Toronto) and the east (1908: Town of East Toronto) and the west (1909: the City of West Toronto—The Junction). After many attempts to force the TRC to serve these areas, the City created its own street railway operation, the Toronto Civic Railways to do so, and built several routes. Repeated court battles forced the TRC to build new cars, but they were of old design. When the TRC franchise ended in 1921, the Toronto Transportation Commission (TTC) was created, combining the city-operated Toronto Civic Railways lines into its new network.

The TTC began in 1921 as solely a streetcar operation, with the bulk of the routes acquired from the private TRC and merged with the publicly operated Toronto Civic Railways.

In 1923, the TTC took over the Lambton, Davenport and Weston routes of the Toronto Suburban Railway (TSR) and integrated them into the streetcar system.

In 1925, routes were operated on behalf of the Township of York (as Township of York Railway), but the TTC was contracted to operate them. One of these routes was the former TSR Weston route.

In 1927, the TTC became the operator of three radial lines of the former Toronto and York Radial Railway. The TTC connected these lines to the streetcar system in order to share equipment and facilities, such as carhouses, but the radials had their own separate management within the TTC's Radial Department. The last TTC-operated radial (North Yonge Railways) closed in 1948.

Abandonment plans (1945–1989)

After the Second World War, many cities across North America and Europe[7] began to eliminate their streetcar systems in favour of buses. During the 1950s, the TTC continued to invest in streetcars and the TTC took advantage of other cities' streetcar removals by purchasing extra PCC cars from Cleveland, Birmingham, Kansas City, and Cincinnati.

In 1966, the TTC announced plans to eliminate all streetcar routes by 1980. Streetcars were considered out of date, and their elimination in almost all other cities made it hard to buy new vehicles and maintain the existing ones. Metro Toronto chair William Allen claimed in 1966 that "streetcars are as obsolete as the horse and buggy".[8] Many streetcars were removed from service when Line 2 Bloor–Danforth opened in February 1966.

The plan to abolish the streetcar system was strongly opposed by many in the city, and a group named "Streetcars for Toronto" was formed to work against the plan. The group was led by professor Andrew Biemiller and transit advocate Steve Munro. It had the support of city councillors William Kilbourn and Paul Pickett, and urban advocate Jane Jacobs. Streetcars for Toronto presented the TTC board with a report that found retaining the streetcar fleet would in the long run be cheaper than converting to buses. This combined with a strong public preference for streetcars over buses changed the decision of the TTC board.[9][10]

The TTC then maintained most of its existing network, purchasing new custom-designed Canadian Light Rail Vehicles (CLRV) and Articulated Light Rail Vehicles (ALRV). It also continued to rebuild and maintain the existing fleet of PCC (Presidents' Conference Committee) streetcars until they were no longer roadworthy.

The busiest north–south and east–west routes were replaced respectively by the Yonge–University and the Bloor–Danforth subway line, and the northernmost streetcar lines, including the North Yonge and Oakwood routes, were replaced by trolley buses (and later by diesel buses).

Two lines that operated north of St. Clair Avenue were abandoned for other reasons. The Rogers Road route was abandoned to free up streetcars for expanded service on other routes.[11] The Mount Pleasant route was removed because of complaints that streetcars slowed automobile traffic. Earlier, the TTC had contemplated abandonment because replacement by trolley buses was cheaper than replacing the aging tracks.[12]

When Kipling station opened in 1980 as the new western terminus of Line 2 Bloor–Danforth, it had provision for a future streetcar or LRT platform opposite the bus platforms. However, there was no further development for a surface rail connection there.[13]

In the early 1980s, a streetcar line was planned to connect Kennedy station to Scarborough Town Centre. However, as that line was being built, the Province of Ontario persuaded the TTC to switch to using a new technology called the Intermediate Capacity Transit System (now Bombardier Innovia Metro) by promising to pay for any cost overruns (which eventually amounted to over $100 million). Thus, the Scarborough RT (now Line 3 Scarborough) was born, and streetcar service did not return to Scarborough.[14]

Expansion period (1989–2000)

The TTC returned to building new streetcar routes in 1989. The first new line was route 604 Harbourfront, starting from Union station, travelling underneath Bay Street and rising to a dedicated centre median on Queen's Quay (along the edge of Lake Ontario) to the foot of Spadina Avenue. This route was lengthened northward along Spadina Avenue in 1997, continuing to travel in a dedicated right-of-way in the centre of the street, and ending in an underground terminal at Spadina station. At this time, the route was renamed 510 Spadina to fit with the numbering scheme of the other streetcar routes. This new streetcar service replaced the former route 77 Spadina bus, and since 1997 has provided the main north-south transit service through Toronto's Chinatown and the western boundary of University of Toronto's main campus. The tracks along Queen's Quay were extended to Bathurst Street in 2000 to connect to the existing Bathurst route, providing for a new 509 Harbourfront route from Union Station to the refurbished Exhibition Loop at the Exhibition grounds, where the Canadian National Exhibition is held.

21st century (2001–present)

.jpg)

By 2003, two-thirds of the city's streetcar tracks were in poor condition as the older track was poorly built using unwelded rail attached to untreated wooden ties lying on loose gravel. The result was street trackage falling apart quickly requiring digging up everything after 10–15 years. Thus, the TTC started to rebuild tracks using a different technique. With the new technique, concrete is poured over compacted gravel, and the ties are placed in another bed of concrete, which is topped by more concrete to embed rail clips and rubber-encased rails. The resulting rail is more stable and quieter with less vibration. The new tracks are expected to last 25 years after which only the top concrete layer needs to be removed in order to replace worn rails.[15][16]

Route 512 St. Clair was rebuilt to restore a separated right-of-way similar to that of the 510 on Spadina Avenue, to increase service reliability and was completed on June 30, 2010.[17]

On December 19, 2010, 504 King streetcar service returned to Roncesvalles Avenue after the street was rebuilt to a new design which provided a widened sidewalk "bumpout" at each stop to allow riders to board a streetcar directly from the curb. When no streetcar is present, cyclists may ride over the bumpout as it is doubles as part of a bike lane.[18][19]

On October 12, 2014, streetcar service resumed on 509 Harbourfront route after the street was rebuilt to a new design that replaced the eastbound auto lanes with parkland from Spadina Avenue to York Street. Thus, streetcars since then run on a roadside right-of-way immediately adjacent to a park on its southern edge.[20]

The Toronto Transit Commission eliminated all Sunday stops on June 7, 2015, as these stops slowed down streetcars making it more difficult to meet scheduled stops. Sunday stops, which served Christian churches, were deemed unfair to non-Christian places of worship, which never had the equivalent of a Sunday stop. Toronto originally created Sunday stops in the 1920s along its streetcar routes to help worshippers get to church on Sunday.[21]

On November 22, 2015, the TTC started to operate its new fleet of Flexity streetcars from its new Leslie Barns maintenance and storage facility.[22]

On December 14, 2015, the TTC introduced Presto, proof-of-payment and all door loading for all streetcars on all routes. All streetcar passengers are required to carry proof that they have paid their fares such as a validated TTC ticket, paper transfer, pass or Presto card while riding.[23]

With the January 3, 2016, service changes, 510 Spadina became the first wheelchair-accessible streetcar route. All CLRV streetcars were expected to be withdrawn from the route, thus leaving only Flexity streetcars operating. However, CLRV and ALRV streetcars will be used as backup in the event of an insufficient availability of Flexity streetcars.[24]

On June 19, 2016, the TTC launched the 514 Cherry streetcar route, to supplement 504 King service along King Street between Dufferin and Sumach streets. The new route operated every 15 minutes or better and used the Commission's new accessible Flexity streetcars.[25] The eastern end of the 514 route ran on a newly constructed branch, originally dubbed the Cherry Street streetcar line, which is located in a reserved side-of-street right-of-way.[26]

On September 12, 2017, 509 Harbourfront became the first streetcar route in Toronto to operate Flexity streetcars with electrical pickup by pantograph instead of trolley pole.[27]

On October 7, 2018, the 514 Cherry route was permanently cancelled. The service it provided was replaced by the 504 King, which was divided into two overlapping branches, each to one of the termini (Dufferin Gate Loop and Distillery Loop) of the former 514 route.[28]

Incidents

On December 16, 2010, the TTC suffered its worst accident since the Russell Hill subway crash in 1995. Up to 17 people were sent to hospital with serious but non-life-threatening injuries after a 505 Dundas streetcar heading eastbound collided with a Greyhound bus at Dundas and River Streets.[29]

Routes

Based on 2013 statistics, the TTC operated 304.6 kilometres (189.3 mi)[2] of routes on 82 kilometres (51 mi) streetcar network (double or single track) throughout Toronto.[1][2] There are 10 regular streetcar routes on the TTC network. [30]

| Nº | Name | Full Length | Notes | Fleet[31] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 501 | Queen | 24.43 km (15.18 mi) | Part of Blue Night Network as 301 Queen | CLRV, ALRV |

| 502 | Downtowner | 9.38 km (5.83 mi) | Operates Monday to Friday during the daytime; 22A Coxwell bus takes over in the evenings and on weekends | Buses |

| 503 | Kingston Rd | 8.97 km (5.57 mi) | Rush hour service only | CLRV |

| 504 | King | 13.97 km (8.68 mi) | Operates as two overlapping branches:

Part of the Blue Night Network service operating as 304 King |

Flexity, CLRV |

| 505 | Dundas | 10.74 km (6.67 mi) | Buses | |

| 506 | Carlton | 14.82 km (9.21 mi) | Part of Blue Night Network as 306 Carlton, also serves College Street | CLRV |

| 509 | Harbourfront | 4.65 km (2.89 mi) | Route operates on a dedicated right-of-way | Flexity |

| 510 | Spadina | 6.17 km (3.83 mi) | Route operates on a dedicated right-of-way, part of the Blue Night Network service | Flexity |

| 511 | Bathurst | 6.47 km (4.02 mi) | Seasonally uses larger vehicles (ALRV, Flexity) to handle Exhibition Place crowds | Buses |

| 512 | St. Clair | 7.01 km (4.36 mi) | Route operates on a dedicated right-of-way | Flexity |

As of 2017, delivery problems with the new Flexity LRVs led to a shortage of streetcars.[32] Because of that shortage, as well as construction projects, some streetcar routes are temporarily replaced partly or entirely with buses.[33]

Some routes operate wholly or partly within their own rights-of-way, and stop on demand at frequent stops.

Route numbers

Until 1980, streetcar routes had names but not numbers. When the CLRVs were introduced, the TTC assigned route numbers in the 500 series. CLRVs have a single front rollsign showing various combinations of route number and destination, while PCC streetcars showed a route identifier (route name until the 1980s and later route number) and destination on two separate front rollsigns.[34] The digital destination signs on the new Flexity Outlook streetcars show route number, route name and destination.[35] Before 2018, streetcar-replacement bus services indicated route number and destination but not route name, like the CLRVs.

The four streetcar-operated Blue Night Network routes have been assigned 300-series route numbers. The other exception to the 500 series numbering was the Harbourfront LRT streetcar. When introduced in 1990, this route was numbered 604, which was intended to group it with the old numbering scheme for rapid transit routes. In 1996, the TTC overhauled its rapid transit route numbers and stopped trying to market the Harbourfront route as 'rapid transit'. The number was changed to 510. The tracks were later extended in two directions to form the 510 Spadina and 509 Harbourfront routes.[36]

During times when streetcar service on all or a portion of a route has been replaced temporarily by buses (e.g., for track reconstruction, major fire, special event, lack of available streetcars), the replacement bus service is typically identified by the same route number as the corresponding streetcar line.

Subway connections

There are underground connections between streetcars and the subway at St. Clair West, Spadina, and Union stations, and streetcars enter St. Clair, Dundas West, Bathurst, Broadview, and Main Street stations at street level. At the eight downtown stations, excepting Union, from Queen's Park to College on Line 1 Yonge–University, streetcars stop on the street outside the station entrances. Union station serves as the hub for both the TTC as well as the GO train system.

Dedicated rights-of-way

The majority of streetcar routes operate in mixed traffic, generally reflecting the original track configurations dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, newer trackage has largely been established within dedicated rights-of-way, in order to allow streetcars to operate with fewer disruptions due to delays caused by automobile traffic. Most of the system's dedicated rights-of-way operate within the median of existing streets, separated from general traffic by raised curbs and controlled by specialized traffic signals at intersections. Queen streetcars have operated on such a right-of-way along the Queensway between Humber and Sunnyside loops since 1957. Since the 1990s, dedicated rights-of-way have been opened downtown along Queens Quay, Spadina Avenue, St. Clair Avenue West, and Fleet Street.

Short sections of track also operate in tunnel (to connect with Spadina, Union, and St. Clair West subway stations). The most significant section of underground streetcar trackage is a tunnel underneath Bay Street connecting Queens Quay with Union Station; this section, which is approximately 700 m (2,300 ft) long, includes one intermediate underground station at Bay Street and Queens Quay.

During the late 2000s, the TTC reinstated a separated right-of-way — removed between 1928 and 1935[37] — on St. Clair Avenue, for the entire 512 St. Clair route. A court decision obtained by local merchants in October 2005 had brought construction to a halt and put the project in doubt; the judicial panel then recused themselves, and the delay for a new decision adversely affected the construction schedule. A new judicial panel decided in February 2006 in favour of the city, and construction resumed in mid-2006. One-third of the St. Clair right-of-way was completed by the end of 2006 and streetcars began using it on February 18, 2007. The portion finished was from St. Clair station (Yonge Street) to Vaughan Road. The second phase started construction in mid-2007 from Dufferin Street to Caledonia Road. Service resumed using the second and third phases on December 20, 2009 extending streetcar service from St. Clair to Earlscourt Loop located just south and west of Lansdowne Avenue. The fourth and final phase from Earlscourt Loop to Gunns Loop (just west of Keele Street) is completed and full streetcar service over the entire route was finally restored on June 30, 2010.[38][39]

Between September 2007 and March 2008, the tracks on Fleet Street between Bathurst Street and the Exhibition Loop were converted to a dedicated right-of-way and opened for the 511 Bathurst and the 509 Harbourfront streetcars. Streetcar track and overhead power line were also installed at the Fleet loop, which is located at the Queen's Wharf Lighthouse.[40][41]

The eastern portion of the 504A King route runs on a side-of-street right-of-way. It was constructed starting in 2012 to support redevelopment in the West Don Lands and the Distillery District, former industrial areas.[25][26]

As part of the King Street Pilot Project, a temporary transit mall was set up along King Street for a one-year trial period starting in mid-November 2017. Although not a dedicated right-of-way, the transit mall achieves the goal of preventing road traffic from impeding streetcar service. Road traffic is discouraged from using the mall by being forced to leave the mall via a right turn at most signalized intersections.[42]

Future expansion

Transit City

The City of Toronto's and the TTC's Transit City report[43] released on March 16, 2007, proposed creating new light rail lines. These are mainly separate from the streetcar network as the track gauge and vehicle specifications are quite different. Much of the original proposal has since been cancelled, and those light-rail lines that are proceeding are classified as part of the Toronto subway system.

Other proposals

The following are proposals to expand the streetcar system that were under consideration in 2015:

- The Waterfront West LRT would run from Long Branch Loop along Lake Shore Boulevard and the Queensway to Colbourne Lodge Drive and then adjacent to the Lake Shore Boulevard to Exhibition Loop and onto Union subway station via Queens Quay. This line originated from the Transit City proposals. It was shelved in 2013 but recommended for reconsideration in 2015 by city staff. In 2017, the TTC revised the proposal as summarized here.[44]

- The East Bayfront LRT is planned to run along Queens Quay East from Union station to complement the 509 Harbourfront line.[44]

- Waterfront Toronto is recommending the creation or extension of three streetcar lines in the Port Lands. Both the Cherry Street streetcar line and East Bayfront LRT would be extended to Queens Quay and Parliament Street. From there, one line would run south on Cherry Street to the Ship Channel and another east along Commissioners Street to Leslie Street. Another line would be built along an extended Broadview Avenue south from Queen Street to Commissioners Street.[45]

Discontinued streetcar routes

Toronto Street Railway

Routes marked to City were operating on May 20, 1891, when the Toronto Street Railway Company's franchise expired and operations were taken over by the City of Toronto.[46]

| Route | Started | Ended | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bathurst | September 1889 | December 7, 1889 | to "Seaton Village" |

| Bloor | May 29, 1891 | to City | |

| Brockton | September 4, 1883 | May 1884 | from "Queen & Brockton"; to "Queen & Brockton" |

| Carlton & College | August 2, 1886 | to City | |

| Church | August 18, 1881 | to City | |

| Danforth | July 8, 1889 | to City | |

| Davenport | August 18, 1890 | to City from "Seaton Village" | |

| Dovercourt via McCaul | September 24, 1888 | to City from "McCaul & College" | |

| Front & McCaul | October 22, 1883 | June 28, 1884 | to "McCaul & College" |

| Front & Parliament | November 25, 1878 | July 25, 1881 | to "Parliament" and "Winchester" |

| High Park via Queen | April 1887 | to City | by this date; from "Queen & Parkdale" |

| King | September 21, 1874 | to City | longest continuously operated route in Toronto |

| King via Strachan | September 2, 1879 | September 19, 1890 | during Toronto Industrial Exhibition only; to "King" |

| Kingston Rd. | June 9, 1875 | April 1887 | Kingston Road Tramway Co.; by this date; part to "Woodbine" |

| Lee | July 15, 1889 | to City | |

| McCaul & College | June 30, 1884 | September 22, 1888 | from "Front & McCaul"; to "Dovercourt via McCaul" |

| McCaul & College | July 15, 1889 | to City from "Dovercourt via McCaul" | |

| Metropolitan | January 26, 1885 | to City Metropolitan Street Railway | |

| Parliament | July 26, 1881 | to City from "Front & Parliament" | |

| Queen | February 2, 1861 | December 7, 1881 | to "Queen & Brockton" |

| Queen | September 4, 1883 | May 1884 | from "Queen & Brockton"; to "Queen & Brockton" |

| Queen & Brockton | December 8, 1881 | September 3, 1883 | from "Queen"; to "Queen & Brockton" |

| Queen & Brockton | May 1884 | to City from "Brockton" and "Queen" | |

| Queen & Parkdale | September 2, 1879 | April 1887 | ended by Q2 1887; to "High Park via Queen" |

| Queen East | May 11, 1885 | to City from "Sherbourne" | |

| Seaton Village | July 27, 1885 | to City from "Spadina & Bathurst" | |

| Sherbourne | December 1, 1874 | to City may have begun a day or two earlier | |

| Spadina | June 1879 | to City | |

| Spadina & Bathurst | June 30, 1884 | July 25, 1885 | from "Spadina"; to "Seaton Village" |

| Toronto Industrial Exhibition | September 13, 1883 | September 19, 1890 | first electric route; operated by steam during the 1891 season |

| Winchester | July 26, 1881 | to City from "Front & Parliament" | |

| Woodbine | May 21, 1887 | to City from "Kingston Rd." | |

| Yonge | November 9, 1861 | – | to City first rail transit route in Toronto |

Toronto Railway Company

Routes marked to TTC were operating on September 21, 1921, when the Toronto Railway Company's operations were taken over by the Toronto Transportation Commission.[47]

| Route | Started | Ended | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur | February 12, 1902 | 1909 | merged with "Dundas" |

| Ashbridge | November 5, 1917 | to TTC | replaced by bus service in the 1920s.[48] |

| Avenue Road | September 2, 1895 | to TTC | |

| Bathurst | July 27, 1885 | to TTC | |

| Belt Line | November 16, 1891 | to TTC | |

| Bloor | 1889 | to TTC | |

| Broadview | October 1892 | to TTC | |

| Brockton | 1882 | October 9, 1893 | renamed "Dundas" |

| Carlton | August 1886 | to TTC | |

| Church | 1881 | to TTC | |

| College | November 1893 | to TTC | |

| Danforth | May 1889 | October 1892 | renamed "Broadview" |

| Davenport | December 1892 | November 1891 | replaced by "Bathurst", "Parliament" and "Winchester" |

| Dovercourt | November 1888 | to TTC | |

| Dufferin | 1889 | September 30, 1891 | merged with "Danforth" |

| Dundas | October 9, 1893 | to TTC | |

| Dupont | August 29, 1906 | to TTC | |

| Harbord | August 29, 1911 | to TTC | |

| High Park | 1886 | 1905 | |

| King | 1874 | to TTC | |

| Lee Avenue | 1889 | May 15, 1893 | merged into "King" |

| McCaul | October 1883 | January 1, 1896 | replaced by "Bloor" |

| Parkdale | 1880 | 1886 | renamed "High Park" |

| Parliament | 1881 | March 4, 1918 | merged into "Queen" |

| Queen | December 2, 1861 | to TTC | |

| Queen East | 1882 | October 16, 1891 | merged with "Danforth" |

| Roncesvalles | 1909 | December 20, 1911 | replaced by "Queen" |

| Seaton Village | July 27, 1885 | October 23, 1891 | replaced by "Davenport", "Parliament" and "Winchester" |

| Sherbourne | November 1874 | November 16, 1891 | merged into "Belt Line" |

| Spadina | 1878 | November 16, 1891 | merged into "Belt Line" |

| Winchester | November 1874 | to TTC | |

| Woodbine | May 1887 | April 4, 1893 | replaced by "King" |

| Yonge | September 11, 1861 | to TTC | |

| York | in operation in October 1891 and discontinued prior to December 31, 1891 | ||

Toronto Civic Railways

All routes transferred to the Toronto Transportation Commission.[49]

| Route | Started | Ended | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloor | November 4, 1914 | to TTC | TCR and TRC Bloor routes merge into Broadview route and later replaced by Bloor–Danforth subway 1966 |

| Danforth | October 30, 1913 | to TTC | Same name, merged with Bloor route and finally replaced by Bloor–Danforth subway 1966 |

| Gerrard | December 18, 1912 | to TTC | Merger as Gerrard-Main route and later merged in Carlton route (now 506 Carlton) |

| Lansdowne | January 16, 1917 | to TTC | Two streetcar routes: Lansdowne (replaced by trolleybus route 1942) and Lansdowne North (replaced by Lansdowne North bus 1925); now part of 47 Lansdowne bus route |

| St. Clair | August 25, 1913 | to TTC | Same route as St. Clair route (now 512 St. Clair) |

Toronto Transportation Commission/Toronto Transit Commission

| Route | Began | Ended | Number | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belt Line | 1891 | 1923 | After 1923, Spadina, Bloor, King and Sherbourne streetcar routes took over operations. Only King and Spadina are still streetcar routes with the remainder replaced by subway or bus service. | |

| Bloor | 1890 | 1966 | Ran multiple unit (MU) cars from 1950 to 1966 and then replaced by Line 2 Bloor–Danforth subway | |

| Cherry | 2016 | 2018 | 514 | Route cancelled as of October 7, 2018 and replaced by branches of 504 King |

| Coxwell | 1921 | 1966 | replaced by 22 Coxwell bus | |

| Dundas Exhibition | 1980 | 1986 | 522 | Also operated during the 1995 season and the 2013 Canadian National Exhibition. |

| Dupont/Bay | 1926 | 1963 | Replaced by 6 Bay bus | |

| Earlscourt | 1954 | 1976 | Merged into 512 St. Clair; assigned number 512L | |

| Fort | 1931 | 1966 | Merged into 511 Bathurst | |

| Harbord | 1911 | 1966 | Replaced by 72 Pape and 94 Wellesley buses | |

| Harbourfront | 1990 | 2000 | 604 | Renumbered as 509 Harbourfront |

| King Exhibition | 1980 | 2000 | 521 | Temporarily reinstated in 2013, and operating as 521 Exhibition East |

| Lake Shore | 1995 | 2015 | 508 | Cancelled due to streetcar shortage. Queen section now served by 501 Queen and King section by 504 King. |

| Long Branch | 1928 | 1995 | 507 | Merged in 501 Queen |

| Oakwood | 1922 | 1960 | Replaced by 63 Ossington trolleycoach (converted to diesel bus route in 1992 when trolleybus fleet retired) | |

| Parliament | 1910 | 1966 | Replaced by 65 Parliament bus | |

| Spadina | 1923 | 1948 | replaced by the 77 Spadina bus; later replaced by the 510 Spadina streetcar in 1997 | |

| Winchester | 1910 | 1924 | Replaced by Yonge and Parliament streetcars (former replaced by subway in 1954 and latter by bus route in 1966); bus route from Parliament Street east to Sumach Street from 1924 to 1930. | |

| Mount Pleasant | 1975 | 1976 | Split from 512 St. Clair; Replaced by 74 Mt. Pleasant trolleycoach until 1991; diesel bus route from St. Clair Station to Mt. Pleasant Loop just north of Eglinton 1976–1977; diesel bus route since 1991 | |

| Rogers Road | 1922 | 1974 | Replaced by 63F Ossington via Rogers trolleycoach, 48 Humber Blvd from 1974 to 1994 and diesel buses from 1992 onwards. In 1994, 161 Rogers Road service replaced both 63F Ossington and 48 Humber Blvd. | |

| Yonge | 1861 | 1954 | Replaced by Line 1 Yonge–University subway, Downtown bus (97 Yonge beginning in 1956), and Yonge trolleycoach until 1973 (replaced with diesel buses). |

Rolling stock

Brief history of TTC acquisitions

When the TTC was created in 1921, it acquired hundreds of cars from its two predecessor companies: the Toronto Railway Company and the Toronto Civic Railways. In 1927, the TTC acquired the radial cars of the former Toronto & York Radial Railway when it took over operation of that system from the Hydro-Electric Railways.[50]

In the 1920s, the TTC purchased new Peter Witt streetcars, and they remained in use into the 1960s. In 1938, the TTC started to operate its first Presidents' Conference Cars (PCC), eventually operating more than any other city in North America. In 1979, the Canadian Light Rail Vehicles entered revenue service,[51] followed by their longer, articulated variants, the ALRVs, in 1988.[52] The last of the PCC vehicles were retired from full-time revenue service in the 1990s.

On August 31, 2014, the TTC started operating its first Bombardier Flexity Outlook vehicles. As more of these new vehicles arrive and enter service, older CLRV and ALRV vehicles are gradually being retired from service.

Streetcar shortage

As of 2018, the TTC has experienced a streetcar shortage not only because of delivery delays of the new Flexity streetcars but also because of a 20% increase in streetcar ridership since 2008. The streetcar fleet capacity has not grown for almost three decades. After delivery of the last of the 204 Flexity cars ordered, the TTC plans to purchase another 60 cars; however, the TTC estimates that would only satisfy demand until 2023 instead of 2027 as originally planned. Bombardier may have the edge on a second order as, if the TTC went with another supplier, a prototype modified for Toronto's track characteristics would not be ready until 2023 with first delivery in 2024 or 2025.[53]

Streetcars purchased by the TTC

Note that not all numbers within a series were used.

| Fleet numbers | Type | In service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2300–2678 2900–3018 | Peter Witt | 1921–1954 | "large" Witts; even numbers only |

| 2700–2898 | Peter Witt | 1922–1965 | "small" Witts; even numbers only. 2766 retained for charters and summer service. |

| 2301–2419 | 2-door trailer | 1921–1938 | odd numbers only |

| 2701–3029 | 3-door trailer | 1923–1954 | "Harvey" trailers; odd numbers only |

| 4000–4299 4575–4601 | PCC | 1938–1971 | air-electric |

| 4300–4574 4625–4779 | PCC | 1947–1995 | all-electric, PCC 4500 and 4549 restored and still maintained[54] |

| 4900 | ALRV | 1982–1983 | prototype; never owned by TTC but by UTDC; used on TTC test runs and returned (later scrapped); painted with similar TTC scheme |

| 4000–4199 | CLRV | 1977–present | will be phased out as Flexity Outlooks start entering service in 2014. 41 cars retired. |

| 4200–4251 | ALRV | 1987–present | articulated; will be phased out when Flexity Outlook start entering service in 2014. 9 cars retired. |

| 4400–4603 | Flexity | 2014–present | 2013: testing; 2014–present: revenue service |

Electrical pickup

The older CLRV and ALRV streetcars have only a trolley pole. New Flexity Outlook streetcars are delivered with both a pantograph as well as a trolley pole. All streetcars in service had been using the trolley pole until September 12, 2017, when 509 Harbourfront became the first route to use the pantograph.[27]

With the introduction of the new Flexity streetcars, the TTC plans to convert the entire system to be pantograph-compatible. The new streetcars need 50% more electrical current than the older streetcars, and use of the trolley pole limits the amount of electricity the new cars can draw from the overhead wire, resulting in reduced performance. One consequence of trolley pole use on the Flexity streetcars is that air conditioning does not function in summer.[55]

Since 2008, the TTC has been converting the streetcar overhead wire to be compatible for pantograph electrical pickup as well as for trolley poles. The overhead over the Fleet Street tracks was the first to be so converted. The new overhead uses different hangers so that pantographs do not strike supporting crosswires. It also uses a different gauge of wire to handle the higher electrical demands of Flexity Outlook streetcars.[56]

During a rainy period in February 2018, the TTC received an incentive to expedite the conversion of the electrical overhead for pantograph use by the Flexity streetcars. On February 20, 2018, Flexity streetcars using trolley poles were pulling down some of the overhead. In Toronto, the tip of the trolley pole has a shoe with a carbon insert to collect current. The carbon insert also lowers the trolley shoe so that it does not strike hangers that are not yet pantograph-compatible. During wet weather, these carbon inserts wear out faster needing replacement after a day or two for older streetcars. However, because the Flexity streetcars draw more current than older streetcars, their carbon inserts wore out faster, in less than 8 hours in the wet weather. (There was also an issue with the quality of carbon the TTC purchased.) With pantographs, this would be less of a problem as the pantograph blades have a larger contact area than a trolley shoe to absorb wear. Because of this incident, the TTC decided it should accelerate the conversion of overhead for pantograph use.[57]

Work to make all the entire streetcar system pantograph-compatible is expected to be completed in 2020. The TTC's schedule to convert the overhead for pantograph use is as follows:[57]

| Route | Expected completion | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 509 Harbourfront | September 12, 2017 | Pantographs in use |

| 510 Spadina | May 14, 2018[58] | Pantographs in use |

| 512 St. Clair | 2018-Q3 | |

| 511 Bathurst | 2018-Q4 | |

| 505 Dundas | 2019-Q2 | |

| 506 Carlton | 2019-Q3 | |

| 502 Downtowner | 2019-Q4 | |

| 503 Kingston Rd | 2019-Q4 | |

| 504 King | 2020-Q1 | |

| 501 Queen | 2020-Q2 |

Winter operational issues

Very cold weather

The fleet of CLRV and ALRV experienced operational issues during extreme cold temperatures in early 2015 as doors and brakes failed as moisture in the pneumatic lines froze. Moisture also caused track sanders to fail. Buses were used to replace streetcars unfit for service, some of which had failed while in service. The new Flexity cars, which use electronic braking and door operations, were unaffected by the weather.[59][60] Cold temperatures in late 2017 and early 2018 caused the same mechanical failures, making about a third of the legacy streetcars inoperable, necessitating the use of buses to cover the shortfall.[61][62]

Freezing rain

The streetcar overhead is vulnerable during freezing rain storms. During such storms, the TTC applies anti-freeze to the overhead wire to prevent ice from interrupting electrical contact. In addition, the TTC attaches "sliders" to trolley poles on every fifth streetcar to knock ice off the overhead wire. The TTC places overhead crews on standby at various locations around the streetcar network to address problems of power loss or overhead wires coming down.[63]

The anti-freeze used on the overheard wire is also applied to streetcar switches on the network. In addition, the TTC runs "storm cars" on all routes to prevent any ice build-up on switches that the anti-freeze could not prevent.[63]

These measures are applied only during freezing rain. However, during the ice storm of April 14–16, 2018, the TTC also used bus substitution on portions of the streetcar network outside the downtown area in order to concentrate streetcars and emergency crews into a smaller area.[63]

Track gauge

The tracks of Toronto's streetcars and subways are built to the unique track gauge of 4 ft 10 7⁄8 in (1,495 mm), 2 3⁄8 in (60 mm) wider than the usual 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge, which Line 3 Scarborough uses.[64] According to Steve Munro, TTC gauge is "English carriage gauge".

That the gauge of the said railways shall be such that the ordinary vehicles now in use may travel on the said tracks, and that it shall and may be lawful to and for all and every person and persons whatsoever to travel upon and use the said tracks with their vehicles loaded or empty, when and so often as they may please, provided they do not impede or interfere with the cars of the party of the second part (Toronto Street Railway), running thereon, and subject at all times to the right of the said party of the second part, his executors, and administrators and assigns to keep the said tracks with his and their cars, when meeting or overtaking any other vehicle thereon.[65]

As wagons were normally built at standard gauge, the streetcar rails were selected to be slightly wider, allowing the wagons to ride on the inside sections of the rail, and the streetcars on the outside. The Williams Omnibus Bus Line changed the gauge of their buses in 1861 to fit this gauge. At the time, track for horsecars was not our modern 'T' rail, but wide and flat, with a raised section on the outside of the rail.

According to the TTC, the City of Toronto feared that the street railway franchise operator, first in 1861, the Toronto Street Railway, then in 1891, the Toronto Railway Company, and in 1921, the TTC, would allow the operation of steam locomotives and freight trains through city streets, as was common practice in Hamilton, Ontario (until the 1950s) and in many US cities, such as New York City and Syracuse, New York.[64]

Standard gauge tracks in the streets would have allowed this, but steam railway equipment could not follow the abrupt curves in the streetcar network. Opposition to freight operation in city streets precluded interchange even with adjacent radial lines even after the lines changed to TTC gauge. Electric railway freight cars could negotiate street curves, but freight operations to downtown were still not allowed until the final few years of radial operation by the TTC.

The unique gauge has remained to this day because the integrated nature of the streetcar network makes it impossible to replace the gauge on part of the network without closing the entire network, which would be unacceptable given the extent of the system and its importance to transportation in Toronto. Some proposals for the city's subway system involved using streetcars in the tunnels, possibly having some routes run partially in tunnels and partially on city streets, so the Toronto subway was built using the same gauge as streetcars, although ultimately streetcars were never used as part of the subway system.

Besides the Toronto streetcar and subway systems, the Halton County Radial Railway uses the Toronto gauge of 4 ft 10 7⁄8 in (1,495 mm) for its museum streetcar line.

Pre-TTC

Before TTC ownership, however, the streetcar gauge was either 4 ft 10 3⁄4 in (1,492 mm) or 4 ft 11 in (1,499 mm) , depending on the historical source, instead of today's 4 ft 10 7⁄8 in (1,495 mm).

According to Raymond L. Kennedy said: "The street railways were built to the horse car gauge of 4 feet 10 and 3/4 inches. (The TTC changed this to 4 10 7/8 and is still in use today even on the subway. [sic])"[66] James V. Salmon said the "city gauge" was 4 ft 10 3⁄4 in.[67] Both these sources were describing a former streetcar junction at the intersection of Dundas and Keele Streets laid entirely to Toronto streetcar gauge until August 1912. The junction was used by both the Toronto Suburban Railway and the Toronto Railway Company.

However, Ken Heard, Consultant Museologist, Canadian Museums Association, was reported to say: "One of the terms of these agreements was that the track gauge was to accommodate wagons. As horse car rail was step rail, the horse cars, equipped with iron wheels with flanges on the inside, ran on the outer, or upper step of the rail. Wagon wheels naturally did not have a flange. They were made of wood, with an iron tire. Wagons would use the inner, or lower step of the rail. The upper step of the rail guided the wagons on the track. In order to accommodate this arrangement, the track gauge had to be 4 feet, 11 inches. As the streets themselves were not paved, this arrangement permitted wagons carrying heavy loads a stable roadbed."[65] In support of Heard's statement about the pre-TTC gauge, the Charter of the Toronto Railway Company said "the gauge of system (4 ft. 11 in.) is to be maintained on main lines and extensions thereof".[68]

Properties

Dedicated station

Queens Quay is the one standalone underground station that does not connect to the subway. It is located in the tunnel, shared by the 509 Harbourfront and 510 Spadina routes, between Queens Quay West and Union subway station.

Loops

Since all of Toronto's current streetcars are single-ended, turning loops are provided at the normal endpoints of each route and at likely intermediate turnback locations. A routing on-street around one or more city blocks may serve as a loop, but most loops on the system are wholly or partly off-street. Many of these are also interchange points with subway or bus services.

Carhouses

Toronto's streetcars are housed and maintained at various carhouses or "streetcar barns":

| Yard | Location | Year opened | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hillcrest Complex | Davenport Road and Bathurst Street | 1924 | Newly built by TTC on former site of farm and later Toronto Driving Club track; services streetcars and buses, repair facilities |

| Roncesvalles Carhouse | Queen Street West and Roncesvalles Avenue | 1895 (for TRC); rebuilt 1921 (by TTC) | Property acquired Toronto Railway Company, but new carbarn built in 1921 with indoor inspection and repair facility and outdoor streetcar storage tracks |

| Russell (Connaught Avenue) Carhouse | Connaught Avenue and Queen Street East | 1913 (by TRC and 1916 carhouse added); 1924 (rebuilt by TTC) | Built for the Toronto Railway Company as paint shop and 1916 carhouse built to replace King carhouse lost to a fire in 1916; acquired by the TTC in 1921 and rebuilt in 1924 with indoor maintenance facility and outdoor streetcar storage tracks |

| Leslie Barns | Leslie Street and Lake Shore Boulevard East – southeast corner | November 2015 | Carhouse opened November 2015 and receiving some of Flexity fleet (100 of the 204 cars);[69] fully opened in early 2016 |

Inactive carhouses once part of the TTC's streetcar operations:

| Yard | Location | Year opened | Year closed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danforth Carhouse | Danforth Avenue and Coxwell Avenue | 1915; 1921–22 (additions by TTC) | 2002 | built for the Toronto Civic Railways in 1915 and additional indoor storage added by TTC in 1921–22; re-purposed as bus garage in 1967; closed in 1921 but still used by TTC for storage and office space |

| Dundas Carhouse[70] | Dundas Street West and Howard Park Avenue | 1907 | 1936 | Original acquired from TRC (built in 1907), but carhouse was demolished in 1921 but retained for storage for 60 cars; wye and runaround loop since disappeared and area re-developed with cars moving to Roncesvalles |

| Eglinton (Yonge) Carhouse | Eglinton Avenue West and Yonge Street | 1922 | 2002; demolished | Built to replace TRC Yorkville Carhouse and retired as carhouse in 1948 to become bus garage until 2002; most of facility now demolished and remainder used as temporary bus terminal |

| George Street Yard | 170 The Esplanade East | 1894? | 1960s | Used to store and scrap streetcars; now part of David Crombie Park built along with the St. Lawrence housing project (built between 1960s to 1990s) |

| Harbour Yard | Lakeshore Boulevard between Bay and York Streets | 1951 | 1954 | Built as temporary outdoor storage space for Peter Witt cars after Eglinton Carhouse closed to streetcars; tracks removed 1954; now site of parking lot and office towers |

| Lansdowne Carhouse | Lansdowne Avenue and Paton Avenue | 1911 | 1996; demolished 2003 | Built for the Toronto Railway Company and acquired by TTC in 1921; became a trolley bus garage in 1947 and streetcar storage ended 1967; abandoned after 1996 and demolished 2003 |

| TRC Motor Shops | 165 Front Street East | 1886–1887 | 1924 | Built for Toronto Street Railway near St Lawrence Market as horse stables and became electrical generating plant 1891 after horsecar converted to electric car operations by Toronto Railway Company; later as storage space 1906 and acquired by TTC in 1921; used until 1924 and deemed surplus in 1970s; sold to Young People's Theatre 1977 |

| St. Clair (Wychwood) Carhouse | Wychwood south of St. Clair Avenue West | 1914 | 1978 | Built for the Toronto Civic Railways in 1914 and expanded 1916. Acquired by TTC in 1921 with renovations and renamed as Wychwood Barns; closed in 1978 after cars moved to Roncesvalles but continued to be used for storage until the 1990s; tracks removed and restored as community centre. |

| Yorkville Carhouse | Between Scollard Street and Yorkville Avenue west of Yonge Street | 1861 | 1922 | Built in 1861 for Toronto Street Railway and acquired by TRC in 1891, the two-storey carhouse was closed by TTC in 1922; later demolished and now site of condominium and Townhall Square Park |

Source: The TTC's Active Carhouses

Operator training

A mockup of a CLRV used to train new streetcar operators is located at Hillcrest.[71] The training simulator consists of an operator cab, front steps and part of the front of a streetcar.

In September 2014, Chris Bateman, writing in the Toronto Life magazine, described being allowed to try out the new simulator designed for the Flexity vehicles.[71] It provides an accurate mockup of the driver's cab of the Flexity vehicle, with a wrap-around computer screen that provides a convincing simulcra of Toronto streets. Like an aircraft cockpit simulator, this Flexity simulator provides realistic tactile feedback to the driver-trainee. The trainer can alter the simulated weather, the track friction, and can introduce more simulated vehicles on the simulated roadway, and even have badly behaved pedestrians and vehicles unpredictably block the Flexity's path.

Bateman wrote that the analogue simulator for the CLRVs was being retired.[71]

Operators also train with a real streetcar. Front and rear rollsigns on the vehicle identify it as a training car.

Blacksmith

As the TTC's CLRV/ALRV streetcar fleet has aged, many parts used by these older streetcars are no longer available. Thus, the TTC employs a blacksmith to craft parts and tools used to maintain the fleet.[72]

See also

- Toronto Transit Commission bus system

- Queen subway line

- Light rail in Canada

- List of North American light rail systems by ridership

- Streetcars in North America (for other streetcar lines in North America)

- Metrolinx light rail projects in Toronto (formerly Transit City)

- TTC Birney Cars (a model of streetcars operated by the TTC)

References

Inline citations

- 1 2 3 "Toronto's Streetcar Network – Past to Present – History". 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "2013 TTC Operating Statistics". Toronto Transit Commission. 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Public Transportation Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2016" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association (APTA). March 3, 2017. p. 34. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- 1 2 "Public Transportation Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2016" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association (APTA). March 3, 2017. p. 31. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ↑ http://www.urbanrail.net/am/toro/tram/toronto-tram.htm

- ↑ The Canadian Light Rail Vehicles – Transit Toronto

- ↑ Costa, Alvaro; Fernandes, Ruben (February 2012). "Urban public transport in Europe: Technology diffusion and market organisation". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 46 (2): 269–284. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2011.09.002. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Bragg, William (November 13, 1967). "Our Streetcars are Near the End of the Line". Toronto Star. p. 7.

- ↑

Thompson, John (April 5, 2017). "Renewing TTC's surface-running streetcar track". Railway Age. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) owns and operates more than 200 single-track miles of surface streetcar track, including loops, yards and carhouses.

- ↑ Cal, Craig (December 1, 2007). "Streetcars for Toronto – 35th Anniversary". Spacing. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010.

- ↑ Bow, James (August 14, 2017). "The Township of York Railways (Deceased)". Transit Toronto. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ↑ Bow, James (April 21, 2013). "The Mount Pleasant Streetcar (Deceased)". Transit Toronto. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Kipling". Transit Toronto. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

A cutaway of the elevations of Kipling and Kennedy station, showing planned LRT platforms. Image courtesy the Toronto Archives and Nathan Ng's Station Fixation web site.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions About Toronto's Subway And The Scarborough RT". Transit Toronto. July 20, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

Why was the Kennedy RT station renovated so soon after it was built?

- ↑ Munro, Steve (October 25, 2009). "Streetcar Track Replacement Plan 2010–2014". Steve Munro. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ↑ Abbate, Gay (July 14, 2003). "State of tracks forces streetcars to crawl". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 14, 2003.

- ↑

Alter, Lloyd (November 25, 2013). "Streetcars save cities: A look at 100 years of a Toronto streetcar line". TreeHugger. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

A hundred years ago, a new streetcar line was installed on St. Clair Avenue in Toronto in a dedicated right-of-way. In 1928 they got rid of the right-of-way to make more room for cars; In 2006 they rebuilt it again, putting the right of way back.

- ↑ "Lanes, tracks and bikes". Roncesvalles Village BIA.

- ↑ Munro, Steve (December 19, 2010). "Parliament and Roncesvalles 2010 Track Work". Steve Munro. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ↑ Munro, Steve (October 12, 2014). "Streetcars Return to Queens Quay". Steve Munro. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ Andrew-Gee, Eric (May 7, 2015). "Sunday streetcar stops near churches to be shuttered in June". Toronto Star. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ↑ "TTC's new streetcar facility to enter service this Sunday". Toronto Transit Commission. November 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Proof-of-Payment (POP)". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ↑ Munro, Steve (December 4, 2015). "TTC Service Changes Effective January 3, 2016". Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- 1 2 "Introducing 514 Cherry". Toronto Transit Commission. June 20, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- 1 2 Morrow, Adrian (May 25, 2012). "A tiny perfect streetcar line is being laid along Cherry Street". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- 1 2 Munro, Steve (September 12, 2017). "Pantographs Up On Harbourfront". Steve Munro. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ↑ "The current section is Service Advisories 504 King and 514 Cherry route changes". Toronto Transit Commission. October 7, 2018. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Schoolchildren returning from field trip hurt in streetcar crash: report

- ↑ Doherty, Brennan (June 18, 2016). "TTC launches new 514 Cherry St. streetcar route". Toronto Star. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ "October 7, 2018 to November 17, 2018" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ↑ Byford, Andy (December 20, 2016). "New Streetcar Delivery and Claim Negotiation Update" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Accessible streetcar service updates". Toronto Transit Commission. November 12, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ↑ Bow, James (February 7, 2017). "The Canadian Light Rail Vehicles (The CLRVs)". Transit Toronto. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

Some Torontonians also didn't like it when the streetcar route names like QUEEN and KING were removed from the front rollsigns, in favour of route numbers like 501 and 504, and some blamed the CLRV's single rollsign design for this change.

- ↑ Bow, James (September 14, 2017). "The Toronto Flexity Light Rail Vehicles (LRVs)". Transit Toronto. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

Photographer Patrick Duran captured this image of Flexity LRV #4416 operating in 501 QUEEN service eastbound at Queen and Bay on May 7, 2016. The streetcar is likely coming off duty from Spadina Avenue, but the destination sign suggests it's still picking up passengers.

photo - ↑ Bow, James (November 10, 2006). "Route 509 – The New Harbourfront Streetcar". Transit Toronto. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ↑ Route 512 – The St Clair Streetcar

- ↑ http://www3.ttc.ca/Service_Advisories/Construction/St_Clair_Avenue_West_Transit_Improvements_Project_-_Phase_4.jsp

- ↑ Kalinowski, Tess (June 30, 2010). "Finally, St. Clair streetcar fully restored". The Star. Toronto.

- ↑ https://transit.toronto.on.ca/archives/weblog/2007/09/03-fleet_stre.shtml

- ↑ https://transit.toronto.on.ca/archives/weblog/2008/03/29-streetcars.shtml

- ↑ Rider, David (December 12, 2017). "King St. pilot project moving streetcar riders quicker, city says". Toronto Star. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Transit City". City of Toronto. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- 1 2 "Waterfront Transit Update" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Port Lands + South of Eastern – Transportation + Servicing" (PDF). Waterfront Toronto. November 11, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ↑ John F. Bromley (October 25, 2001). "Toronto Street Railway Routes". Transit Canada. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ Pursley, Louis H. (1958). Street Railways of Toronto: 1861–1921. Los Angeles: Interurbans Press. pp. 39–45.

- ↑ Bow, James (April 3, 2012). "The Ashbridge Streetcar (Deceased)". Transit Toronto. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ↑ "The Toronto Civic Railways", UCRS Bulletin, Toronto: Upper Canada Railway Society (26), pp. 1–2

- ↑ John F. Bromley (1979). TTC '28; the electric railway services of the Toronto Transportation Commission in 1928. Upper Canada Railway Society. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ↑ Thompson, John (January 5, 2018). "The car that saved Toronto's streetcars". Railway Age. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ↑ Bow, James (January 30, 2017). "The Articulated Light Rail Vehicles (The ALRVs)". Transit Toronto. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ↑ Spurr, Ben (June 6, 2018). "Bombardier has inside track for TTC's next streetcar order". Toronto Star. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ↑ "A History of Toronto's Presidents' Conference Committee Cars (the PCCs) – Transit Toronto – Content". transit.toronto.on.ca. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ↑ "New Streetcar Implementation Plan" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. June 24, 2013. p. 22. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

New cars draw over 50% more current than the old cars. Low voltage problems will result in reduced performance (i.e. no A/C in summer).

- ↑ Mackenzie, Robert (September 29, 2008). "Streetcars Roll Along Fleet Street Tomorrow". Transit Toronto. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- 1 2 Munro, Steve (April 27, 2018). "Problems With Trolley Shoes on Flexity Cars". Steve Munro. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ O'Neil, Lauren (May 15, 2018). "The TTC is rolling out a new type of streetcar technology". blogTO. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

Pantograph on Spadina, @bradTTC/@TTCStuart ... 1:15 PM - May 14, 2018 · 1 Spadina Crescent

- ↑ "Some TTC streetcars out of service due to cold weather". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. January 8, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ↑ Kalinowski, Tess (January 7, 2015). "TTC warns of chilly waits as cold freezes streetcar service". Toronto Star. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Nearly one-third of old streetcars were unable to leave yard due to frigid weather: TTC". Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Fox, Chris (January 5, 2018). "Frigid temperatures impacting transit service". CP24. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Service changes in the event of an ice storm". Toronto Transit Commission. April 16, 2018. Archived from the original on April 16, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- 1 2

Kalinowski, Tess (January 6, 2010). "Transit City measures up to international standard". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on August 6, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

TTC gauge is `English carriage gauge' and was used in Toronto well before the TTC was formed," explains transit blogger Steve Munro. "There were two purposes: One was to make it impossible for the steam railways to use city tracks and the other (alleged) was to allow carriages and wagons to drive on the tracks when roads were impassable due to mud.

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Questions about Toronto's Streetcars". Transit Toronto. 3 January 2003. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Kennedy, Raymond L. (2009). "The Junction and Its Railways". TrainWeb. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ Salmon, James V. (1958). Rails from the Junction. Lyon Productions. p. 7. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ City solicitor (1892). "The charter of the Toronto Railway Company". City of Toronto. p. 21. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Ashbridges Bay Light Rail Vehicle (LRV) Maintenance and Storage Facility". ttc.ca. Toronto Transit Commission. May 2010. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.stevemunro.ca/?p=392

- 1 2 3

Bateman, Chris (September 29, 2014). "The TTC's new life-sized streetcar simulator is not a toy—but it looks like one". Toronto Life. Archived from the original on September 30, 2014.

Halfway down a long corridor inside the TTC's Hillcrest facility, on Bathurst Street, there's a room marked "streetcar simulator." Inside is a state-of-the-art training device on which the next generation of TTC streetcar drivers will earn their wheels.

- ↑ "Meet Pat Maietta, the TTC's last remaining blacksmith". CBC News. January 27, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

Other references

- Gray, Jeff (June 23, 2005). "TTC to shop for new streetcars". The Globe and Mail.

- "Future Streetcar Fleet Requirements and Plans". Toronto Transit Commission. June 22, 2005.

- Livett, Christopher. "Toronto's Streetcar System (schematic track map)". Transit Toronto.

- Kalinowski, Tess (April 28, 2009). "A streetcar named Inspire?". Toronto Star. Retrieved October 4, 2014. – includes a timeline of the history of the Toronto streetcar system

- "Opportunities for New Streetcar Routes" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. January 21, 1997.

- "North America – Canada – Ontario – Toronto Streetcar (Tram)". UrbanRail.Net. 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toronto streetcar system. |

Route map:

_(14918534190).jpg)