Winchester, Virginia

| Winchester, Virginia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Independent city | ||

| City of Winchester | ||

Loudoun Street Mall, May 2016 | ||

| ||

Winchester  Winchester  Winchester  Winchester | ||

| Coordinates: 39°11′N 78°10′W / 39.183°N 78.167°WCoordinates: 39°11′N 78°10′W / 39.183°N 78.167°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Virginia | |

| County | Frederick | |

| Founded | 1752 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | John David Smith Jr.[1] | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 9.3 sq mi (24 km2) | |

| • Land | 9.2 sq mi (24 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0 km2) | |

| Elevation | 725 ft (221 m) | |

| Population (2017) | ||

| • Total | 27,932 | |

| • Density | 3,036/sq mi (1,172/km2) | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | |

| Zip Code | 22601, 22602, 22603, 22604 | |

| Area code(s) | 540 | |

| FIPS code | 51-86720[2] | |

| GNIS feature ID | 1498552[3] | |

| Website | http://www.winchesterva.gov/ | |

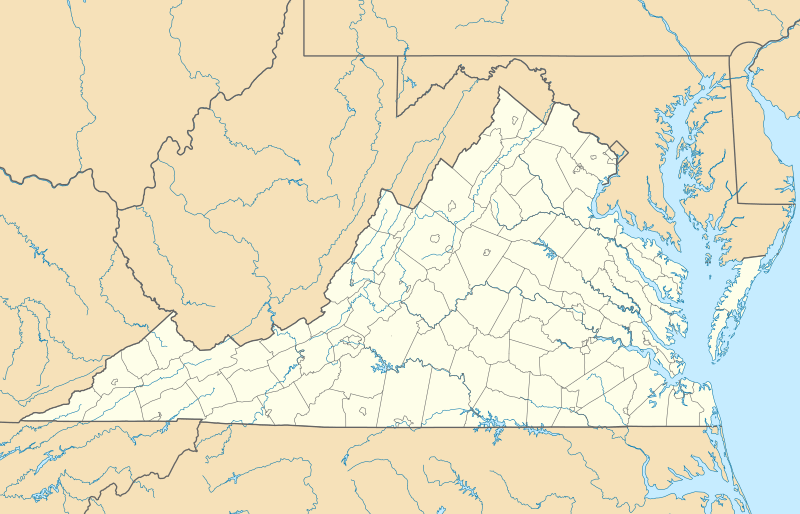

Winchester is an independent city located in the northwestern portion of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 26,203.[4] As of 2015, its population is an estimated 27,284.[5] It is the county seat of Frederick County,[6] although the two are separate jurisdictions. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Winchester with surrounding Frederick County for statistical purposes.

Winchester is the principal city of the Winchester, Virginia-West Virginia Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is a part of the Washington-Baltimore-Northern Virginia, DC-MD-VA-WV Combined Statistical Area. Winchester is home to Shenandoah University and the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley.

History

Native Americans

Indigenous peoples lived along the waterways of present-day Virginia for thousands of years before European contact. Archeological, linguistic and anthropological studies have provided insights into their cultures. Though little is known of specific tribal movements before European contact, the Shenandoah Valley area, considered a sacred common hunting ground, appears by the 17th century to have been controlled mostly by the local Iroquoian-speaking groups, including the Senedo and Sherando.

The Algonquian-speaking Shawnee began to challenge the Iroquoians for the hunting grounds later in that century. The explorers Batts and Fallam in 1671 reported the Shawnee were contesting with the Iroquoians for control of the valley and were losing. During the later Beaver Wars, the powerful Iroquois Confederacy from New York (particularly Seneca from the western part of the territory) subjugated all tribes in the frontier region west of the Fall Line.

By the time European settlers arrived in the Shenandoah Valley around 1729, the Shawnee were the principal occupants in the area around Winchester. During the first decade of white settlement, the valley was also a conduit and battleground in a bloody intertribal war between the Seneca and allied Algonquian Lenape from the north, and their distant traditional enemies, the Siouan Catawba in the Carolinas. The Iroquois Six Nations finally ceded their nominal claim to the Shenandoah Valley at the Treaty of Lancaster (1744). The treaty also established the right of colonists to use the Indian Road, later known as the Great Wagon Road.

The father of the historical Shawnee chief Cornstalk had his court at Shawnee Springs (near today's Cross Junction, Virginia) until 1754. In 1753, on the eve of the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War), messengers came to the Shawnee from tribes further west, inviting them to leave the Valley and cross the Alleghenies, which they did the following year.[7][8] The Shawnee settled for some years in the Ohio Country before being forced by the US government under Indian Removal in the 1830s to remove to Indian Territory.

Winchester had a notable role as a frontier city in those early times. The Governor of Virginia, as well as the young military commander George Washington, met in the town with their Iroquois allies (called the "Half-Kings"), to coordinate maneuvers against the French and their Native American allies during the French and Indian War.

European exploration

French Jesuit expeditions may have first entered the valley as early as 1606, as the explorer Samuel de Champlain made a crude map of the area in 1632. The first confirmed exploration of the northern valley was by the explorer John Lederer, who viewed the it from the current Fauquier and Warren County line on August 26, 1670. In 1705 the Swiss explorer Louise Michel and in 1716 Governor Alexander Spotswood did more extensive mapping and surveying.

In the late 1720s, Governor William Gooch promoted settlement by issuing large land grants. Robert "King" Carter, manager of the Lord Fairfax proprietorship, acquired 200,000 acres (810 km2). This combination of events directly precipitated an inrush of settlers from Pennsylvania and New York, made up of a blend of Quakers and German and Scots-Irish homesteaders, many of them new immigrants. The Scots-Irish comprised the most numerous group of immigrants from the British Isles before the American Revolutionary War.[9]

European settlement

The settlement of Winchester began as early as 1729, when Quakers such as Abraham Hollingsworth migrated up (south) the Great Valley along the long-traveled Indian Path (later called the Great Wagon Road by the colonists) from Pennsylvania. He and others began to homestead on old Shawnee campgrounds. Tradition holds that the Quakers purchased several tracts on Apple-pie Ridge from the natives, who did not disturb those settlements.[10]

The first German settler appears to have been Jost Hite in 1732, who brought ten other families, including some Scots-Irish. Though Virginia was an Anglican colony, Governor William Gooch had a tolerant policy on religion. The availability of land grants brought in many religious families, who were often given 50-acre (200,000 m2) plots through the sponsorship of fellow-religious grant purchasers and speculators. As a result, the Winchester area became home to some of the oldest Presbyterian, Quaker, Lutheran and Anglican churches in the valley. The first Lutheran worship was established by Rev. John Casper Stoever, Jr., and Alexander Ross established Hopewell Meeting for the Quakers. By 1736, Scots-Irish built the Opequon Presbyterian Church in Kernstown.

A legal fight erupted in 1735 when Thomas Fairfax, Sixth Lord Fairfax came to Virginia to claim his land grant. It included "all the land in Virginia between the Rappahannock and the Potomac rivers", an old grant from King Charles II which overlapped and included Frederick County. It took some time for land titles to be cleared among early settlers.

Founding

By 1738 these settlements became known as Frederick Town. The county of Frederick was carved out of Orange County. The first government was created, consisting of a County Court as well as the Anglican Frederick Parish (for purposes of tax collection). Colonel James Wood, an immigrant from Winchester, England, was the first court clerk and had been a surveyor for Orange County, Virginia. He contracted for his own home Glen Burnie homstead around 1737, and it may have been used for early government business.[11] Wood laid out 26 half-acre (2,000 m²) lots in 1744.[11] The County Court held its first session on November 11, 1743, where James Wood served until 1760. Lord Fairfax, understanding that possession is 9/10ths of the law, built a home here (in present-day Clarke County) in 1748.

In February 1752,[12] the Virginia House of Burgesses granted the fourth city charter in Virginia to 'Winchester' as Frederick Town was renamed after Colonel Wood's birthplace in England. In 1754, Abraham Hollingsworth built the local residence called Abram's Delight, which served as the first local Quaker meeting house. George Washington spent a good portion of his young life in Winchester helping survey the Fairfax land grant for Thomas Fairfax, Sixth Lord Fairfax, as well as performing surveying work for Colonel Wood. In 1758 Wood added 158 lots to the west side of town. In 1759 Thomas Lord Fairfax contributed 173 more lots to the south and east.[13]

French and Indian War

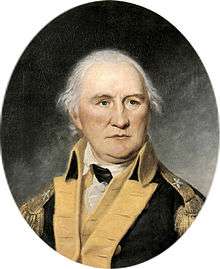

General Edward Braddock's expeditionary march to Fort Duquesne crossed through this area in 1755 on the way to Fort Cumberland. Knowing the area well from work as a surveyor, George Washington accompanied General Braddock as his aide-de-camp. Resident Daniel Morgan joined Braddock's Army as a wagoner on its march to Pennsylvania.

In 1756, on land granted by James Wood, Colonel George Washington designed and began constructing Fort Loudoun, which ultimately covered 0.955 acres (3,860 m2) in present-day downtown Winchester on North Loudoun Street. Fort Loudoun was occupied and manned with guns until the start of the American Revolutionary War.

During this era, a jail was built in Winchester. It occasionally held Quakers from many parts of Virginia who protested the French and Indian War and refused to pay taxes to the Anglican parish. While their cousins in Pennsylvania dominated politics there, Virginia was an Anglican colony and did not tolerate pacifism well. The strong Quaker tradition of pacifism against strong Virginia support for this war and the next, led to long-term stifling of the Quaker population. Winchester became a gateway to Quaker settlements further west; by the mid-19th century, the Quaker population was a small minority here.

During the war in 1758, at the age of 26, Colonel George Washington was elected to represent Frederick County to the House of Burgesses. Daniel Morgan later served as a ranger protecting the borderlands of Virginia against Indian raids, returning to Winchester in 1759. Following the war, from 1763 to 1774 Daniel Morgan served in Captain Ashby's company and defended Virginia against Pontiac's Rebellion and Shawnee Indians in the Ohio valley (that part now in West Virginia).

Revolutionary War

During the Revolutionary War, the Virginia House of Burgesses chose local resident and French and Indian War veteran Daniel Morgan to raise a company of militia to support General George Washington's efforts during the Siege of Boston. He led the 96 men of "Morgan's Sharpshooters" from Winchester on July 14, 1775 and marched to Boston in 21 days. Morgan, Wood, and others also performed duties in holding captured prisoners of war, particularly Hessian soldiers.

Hessian soldiers were known to walk to the high ridge north and west of town, where they could purchase and eat apple pies made by the Quakers. The ridge became affectionately known as Apple Pie Ridge. The Ridge Road built before 1751 leading north from town was renamed Apple Pie Ridge Road. The local farmers found booming business in feeding the Virginia Militia and fledgling volunteer American army.

Following the war, the town's first newspapers, The Gazette and The Centinel, were established. Daniel Morgan continued his public service, being elected to one term in the U.S. House of Representatives (1797–1799).

Civil War

Winchester and the surrounding area were the site of numerous battles during the American Civil War, as the Confederate and Union armies strove to control that portion of the Shenandoah Valley. Seven major battlefields are in the original Frederick County:

Within the city of Winchester:

- The First Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862

- The First Battle of Winchester, May 25, 1862

- The Second Battle of Winchester, June 13–15, 1863

- The Second Battle of Kernstown, July 24, 1864

- The Third Battle of Winchester, September 19, 1864

Near the city of Winchester:

- The Battle of Cool Spring at Snicker's Gap, July 17–18, 1864

- The Battle of Berryville, September 3–4, 1864

- The Battle of Belle Grove (or Cedar Creek), October 19, 1864

Winchester was a key strategic position for the Confederate States Army during the war. It was an important operational objective in Gen Joseph E. Johnston's and Col Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's defense of the Shenandoah Valley in 1861, Jackson's Valley Campaign of 1862, the Gettysburg Campaign of 1863, and the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Including minor cavalry raids and patrols, and occasional reconnaissances, historians claim that Winchester changed hands as many as 72 times and 13 times in one day. Battles raged along Main Street at points in the war. Union General Sheridan and Stonewall Jackson located their headquarters just one block apart at times.

At the north end of the lower Shenandoah Valley, Winchester was a base of operations for major Confederate invasions into the Northern United States. At times the attacks threatened the capital of Washington, D.C. The town served as a central point for troops conducting major raids against the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, and turnpike and telegraph paths along those routes and the Potomac River Valley. For instance, in 1861, Stonewall Jackson removed 56 locomotives and over 300 railroad cars, along with miles of track, from the B&O Railroad. His attack closed down the B&O's main line for ten months. Much of the effort to transport this equipment by horse and carriage centered in Winchester.

During the war, Winchester was occupied by the Union Army for four major periods:

- Major General Nathaniel Banks – (March ? May 12 to 25, 1862, and June 4 to September 2, 1862)

- Major General Robert Milroy – (December 24, 1862, to June 15, 1863)

- Major General Philip Sheridan – (September 19, 1864, to February 27, 1865)

- Major General Winfield Scott Hancock – February 27, 1865, to June 27, 1865

Major General Sheridan raided up the valley from Winchester, where his forces destroyed "2,000 barns filled with grain and implements, not to mention other outbuildings, 70 mills filled with wheat and flour" and "numerous head of livestock," to lessen the area's ability to supply the Confederates.[14]

Numerous local men served with the Confederate Army, mostly as troops. Dr. Hunter McGuire was Chief Surgeon of the Second "Jackson's" Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. He laid the foundations for the future Geneva conventions regarding the treatment of medical doctors during warfare. Winchester served as a major center for Confederate medical operations, particularly after the Battle of Sharpsburg in 1862 and the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863.

Among those who took part in battles at Winchester were future U.S. presidents McKinley and Hayes, both as officers in the Union IX Corps.

Today, Winchester has extensive resources for Civil War enthusiasts. For instance, there are remains of several Civil War-era forts:

- Fort Jackson (a.k.a. Fort Garibaldi, Main Fort, Fort Milroy, Battery No. 2)

- Fort Alabama (a.k.a. Star Fort, Battery No. 3)

- Fort Collier (a.k.a. Battery No. 10)

- Louisiana Heights (a.k.a. the combination of West Fort or Battery No.5 and Battery No. 6)

- Bower's Hill (a.k.a. Battery No. 1)

Jubal Early Drive, which curves south of downtown Winchester, was the central location for many of the battles.

The United States assigned military presence to Winchester and other parts of the South during Reconstruction after the war. Winchester was part of the First Military District, commanded by Major General John Schofield. This period lasted until January 26, 1870.[15]

20th century

Winchester was the first city south of the Potomac River to install electric light. In 1917 the Winchester and Western Railroad connected Winchester with Rock Enon Springs, moving both vacationers and supplies to the resort that is now Camp Rock Enon with far greater speed.[16]:366 Winchester is the location of the bi-annual N-SSA national competition keeping the tradition of Civil War era firearms alive. A three-block section of downtown Loudoun Street was closed to vehicular traffic in the 1970s and is a popular pedestrian area featuring many boutiques and cafes. The street was repaved with brick and landscaped in 2013. Apple Blossom Mall opened in 1982.

Historic sites

National Register of Historic Places

| Site | Year Built | Address | Listed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abram's Delight | 1754 | Parkview Street & Rouss Spring Road | 1973 |

| Douglas School | 1927 | 598 North Kent Street | 2000 |

| Fair Mount | 19th century | 311 Fairmont Avenue | 2004 |

| Glen Burnie | 1794 | 901 Amherst Street | 1979 |

| Handley Library[17] | 1913 | Braddock & Piccadilly Streets | 1969 |

| John Handley High School | 1920s | 425 Handley Boulevard | 1998 |

| Hawthorne and Old Town Spring | 1811 | 610 and 730 Amherst Street | 2013 |

| Hexagon House | 1870s | 530 Amherst Street | 1987 |

| Stonewall Jackson's Headquarters Museum | mid-19th century | 415 North Braddock Street | 1967 |

| Adam Kurtz House | 1757 | Braddock & Cork Streets | 1976 |

| Old Stone Church (Winchester, Virginia) | 1788 | 304 East Piccadilly Street | 1977 |

| Triangle Diner | 1948 | 27 West Gerrard Street | 2010 |

| Winchester Historic District | 1750–1930 | US 522, US 11 & US 50/US 17 | 1980 |

| Winchester Historic District (Boundary Increase) | 120 & 126 North Kent Street | 2003 | |

| Winchester National Cemetery | 1860s | 401 National Avenue | 1996 |

| George Washington's Office Museum | by 1748 | 32 West Cork Street | 1975 |

| Patsy Cline Historic House | 1880 | 608 S. Kent St. | 2005 |

| Mt. Hebron Cemetery and Stonewall Confederate Cemetery | 1844 | 305 E. Boscawen Street | 2008 |

Other sites

In addition to the sites on the National Register of Historic Places, the following historic sites are in Winchester:

- Christ Church (1828)

- Museum of the Shenandoah Valley[18]

- Old Court House Civil War Museum (1840)

- Old Town Winchester (1738)

- Opequon Presbyterian Church and Cemetery (1736)

- Red Lion Tavern (1783)

- Shenandoah Valley Military Academy (1764)

- Site of Historic Fort Loudoun (1756)

- Stonewall Cemetery (1866)

- Kurtz Building (1836)

Geography

Winchester is located at 39°10′41″N 78°10′01″W / 39.178°N 78.167°W.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.3 square miles (24 km2), virtually all of which is land.[19]

It is in the Shenandoah Valley, located between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Allegheny Mountains, and is 15 miles north-northeast of the northern peak of Massanutten Mountain. I-81 passes through the city, along with US 50, US 522, US 17, which ends in the city, and SR 7, which also ends in the city. The city is approximately 75 miles (121 km) to the west of Washington, D.C., 24 miles (39 km) south of Martinsburg, West Virginia, and 25 miles (40 km) north of Front Royal, Virginia.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Winchester has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[20] The hardiness zone is 6b.

| Climate data for Winchester, Virginia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

79 (26) |

88 (31) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

97 (36) |

92 (33) |

81 (27) |

78 (26) |

105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 40 (4) |

44 (7) |

52 (11) |

64 (18) |

73 (23) |

81 (27) |

85 (29) |

84 (29) |

77 (25) |

65 (18) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

64 (18) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 32 (0) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

53 (12) |

62 (17) |

71 (22) |

75 (24) |

74 (23) |

66 (19) |

55 (13) |

46 (8) |

36 (2) |

54 (12) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 23 (−5) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

42 (6) |

51 (11) |

61 (16) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

27 (−3) |

44 (7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−3 (−19) |

7 (−14) |

22 (−6) |

32 (0) |

40 (4) |

49 (9) |

39 (4) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

14 (−10) |

−18 (−28) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.6 (66) |

2.4 (61) |

3.5 (89) |

3.4 (86) |

3.9 (99) |

3.6 (91) |

3.5 (89) |

3.0 (76) |

3.7 (94) |

3.0 (76) |

3.2 (81) |

2.7 (69) |

38.5 (977) |

| Source: [21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 3,454 | — | |

| 1850 | 3,857 | 11.7% | |

| 1860 | 4,392 | 13.9% | |

| 1870 | 4,477 | 1.9% | |

| 1880 | 4,958 | 10.7% | |

| 1890 | 5,196 | 4.8% | |

| 1900 | 5,161 | −0.7% | |

| 1910 | 5,864 | 13.6% | |

| 1920 | 6,883 | 17.4% | |

| 1930 | 10,855 | 57.7% | |

| 1940 | 12,095 | 11.4% | |

| 1950 | 13,841 | 14.4% | |

| 1960 | 15,110 | 9.2% | |

| 1970 | 14,643 | −3.1% | |

| 1980 | 20,217 | 38.1% | |

| 1990 | 21,947 | 8.6% | |

| 2000 | 23,585 | 7.5% | |

| 2010 | 26,203 | 11.1% | |

| Est. 2017 | 27,932 | [22] | 6.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] 1790-1960[24] 1900-1990[25] 1990-2000[26] | |||

As of the census[27] of 2016, the population of Winchester was 27,516. The number of people per square mile was 2957.1/mi²(1141.7/km²). There were 11,907 housing units at an average density of 1279.6 houses per square mile (494.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 81.1% White alone, 11.7% African American, 0.9% Native American, 2.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.46% from other races, and 3.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 16.8% of the population.

There were 10,596 households with an average of 2.49 persons per household. 18.5% of these households spoke a language other than English in the home. The estimated house or condo value[28] was $230,125. The median gross rent was $1,036.

In 2014[28] The median age of the population was 37.6 years. 48.6% of the population was male vs 51.4% being female. For every 100 females, there were 94.6 males.

The median income[27] for a household (from 2012-2016) in the city was $46,466, while the per capita income was $26,984. An estimated 15% of the population was below the poverty line. As of September 2015[28] the unemployment rate was 3.9%

Of those 25 years of age or older, 83.5% of the population[27] had earned a high school degree or higher from 2012-2016, with 31.3% of the population having completed a bachelors degree or higher.

Apple blossom

Winchester is the location of the annual Shenandoah Apple Blossom Festival, which has existed since 1924. It is usually held during the first weekend in May. The festival includes a carnival, firework show, parades, several dances and parties, and a coronation where the Apple Blossom Queen is crowned. Local school systems and many businesses close the Friday of Apple Blossom weekend.[29]

Winchester has more than 20 different "artistic" apples that are made of various materials including wood, rubber pipe, plaster, and paint. These apples were created in 2005 by occupants of the city, and were placed at a specific location at the artists' request after being auctioned off. For example, a bright red apple with a large stethoscope attached to it was placed beside a much-used entrance to the Winchester Medical Center.

Economy

Companies based in Winchester include American Woodmark, Trex, and Rubbermaid Commercial Products.

Federal agencies with operations in Winchester include the Federal Emergency Management Agency,[30] the Federal Bureau of Investigation,[31] and the United States Army Corps of Engineers.[32]

Record manufacturing

Winchester was home to Capitol Record's East Coast Pressing Plant. Capitol Records Distribution Corporation announced in 1968 the purchasing of land in Winchester, Va for a new record processing plant. Along with this plant they built several houses, bought a few small business and later built a tape production plant. The Winchester plant began construction in 1968 and production in 1969. The plant initially had a workforce of 250 people. This plant complemented the other existing manufacturing facilities of Capitol Records in Scranton, PA, Jacksonville, FL and Los Angeles, CA. In 1969 Capitol Records' Pressing Plant in Scranton began phasing out its vinyl manufacturing in favor of the new Winchester plant. Records pressed here include the Beatles' Abbey Road, Simon and Garfunkel's The Concert in Central Park and Richard Pryor's self-titled album. Capitol Records announced in late 1987 that it would end tape duplicating production in the US, in favor of offshore manufacturing, including in Winchester by early 1988, putting more than 500 employees out of work when they closed the Winchester plant.[33]

Top employers

Top employers

According to the City's 2016 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[34] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Valley Health | 1,000 and over |

| 2 | Rubbermaid Commercial Products | 500 - 999 |

| 3 | Winchester City Public Schools | 500 - 999 |

| 4 | Walmart | 500 - 999 |

| 5 | Shenandoah University | 500 - 999 |

| 6 | City of Winchester | 500 - 999 |

| 7 | Axiom Staffing Group | 500 - 999 |

| 8 | Martin's Food Markets | 500 - 999 |

| 9 | Trex | 250 - 499 |

| 10 | Kohl's | 250 - 499 |

Sports

Winchester is home to the Winchester Royals,[35] which is part of the Valley Baseball League, a National Collegiate Athletic Association-sanctioned collegiate summer baseball league in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.[36]

Shenandoah University is located in Winchester and has numerous male and female sports in the Old Dominion Athletic Conference. Winchester is also home to the Winchester Speedway, a 3/8 mile clay oval track, which plays host to a number of touring series, such as the World of Outlaws Late Model Series, and the Lucas Oil Late Model Dirt Series.

Infrastructure

Major highways

- Interstate 81, which runs to Pennsylvania, Roanoke and Tennessee.

- VA 37

- US 11

- VA 7

- US 50

- US 17

- US 522

- SR 657

- SR 628

- SR 661

Transportation

- Winchester Transit provides weekday transit for the city of Winchester.

- Winchester Regional Airport provides general aviation and air taxi service to the area.

- Uber

- Taxicab services

Notable people

18th century

- John H. Aulick (1787-1873), United States Navy officer and veteran of the War of 1812[37]

- Briscoe Baldwin (1789-1852), Virginia delegate and member of the Constitutional Convention[38]

- Rebecca Boone (1739-1813), pioneer and wife of frontiersman Daniel Boone[39]

- Jane Frazier (1735-), frontier woman

- Daniel Morgan (1735-1802), major general of Virginia militia in Revolutionary War; buried at Mount Hebron cemetery

- Michael "Auver Mike" Myers (1745-1852), scout and Indian fighter during the Revolutionary period.[40][41][42]

- Presley Neville (1756-1818), general, Revolutionary War aide-de-camp to the Marquis de Lafayette and Chief Burgess of the Borough of Pittsburgh[43]

- Francis White (-1826), U.S. Representative[44]

- James Wood (1747-1813), brigadier general, Governor of Virginia, son of Winchester's founder

19th century

- Robert T. Barton (1842-1917), Virginia Delegate, Mayor of Winchester and Confederate veteran of the American Civil War[45]

- Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd (1888-1957), pioneering polar explorer

- John Snyder Carlile, (1817-1878), U.S. Senator, instrumental in the creation of West Virginia*U.S. Solicitor General

- Charles Magill Conrad (1804-1878), Secretary of War under President Millard Fillmore

- Holmes Conrad (1840-1915), under President Grover Cleveland and Confederate cavalry Major in the American Civil War

- James William Denver (1817-1892), briefly a Brigadier General in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and for whom the city of Denver, Colorado was named[46]

- Helen H. Gardener (1853-1925), rationalist orator and novelist[47]

- Frederick W. M. Holliday (1828-1899), member of the Confederate Congress during the American Civil War and the Governor of Virginia from 1878 to 1882[48]

- George Hay Lee (1808-1873), United States judge[49]

- Mary Greenhow Lee (1819-1907), diarist during the Civil War

- Cornelia Peake McDonald (1822-1909), diarist during the Civil War[50]

- Hunter McGuire (1835-1900), Chief Surgeon of the Second "Jackson's" Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia*Admiral Louis M. Nulton (1869-1954), superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy (1925-1928) and Commander Battle Fleet (1929-1930).

- Sara Winifred Brown (1868-1948), African American professor and doctor of gynecology. Founded the National Association of University Women, and was the first woman to serve as an alumni trustee of Howard University.

- Spotswood Poles (1887-1962), accomplished baseball player in the precursor to the Negro Leagues

- James Innes Randolph (1837-1887), Confederate Army officer, lawyer, and poet[51]

- John Randolph Tucker (1823-1897), U.S. Representative from Virginia

20th century

- Anne Tucker McGuire, (1913-1988) was an American-born actress who appeared largely in British films and television[52]

- Joe Bageant (1946-2011), writer and journalist[53]

- Brian Benben (1956-), actor[54]

- Harry F. Byrd, Jr. (1914-2013), politician and U.S. Senator[55]

- Lang Campbell (1981-), professional football quarterback[56]

- Patsy Cline (1932-1963), country/pop vocalist and music icon, born in Winchester,[57] interred at Shenandoah Memorial Park.

- Doug Creek (1969-), professional baseball player[58]

- Claude Dallas (1950-), self-styled mountain man convicted of voluntary manslaughter in the deaths of two game wardens in Idaho.[59]

- Penny DeHaven (1948-2014), country music singer[60]

- John Gilkerson (1985-), professional soccer player

- Erick Green (1991-), professional basketball player[61]

- Jack Holt (1888-1951), actor

- John Kirby (1908-1952), jazz musician

- Mark McFarland (1978-), NASCAR driver

- Devon McTavish (1984-), professional soccer player with D.C. United[62]

- J. Kenneth Robinson (1916-1990), U.S. Representative

- Rick Santorum (1958-), presidential candidate, former U.S. senator[63]

- Henry H. Whiting (1923-2012), Justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia

- James "Clayster" Eubanks (1992-), professional Call of Duty player[64]

Sister cities

Winchester's first sister city, Winchester, England, is where the Virginia town gets its name. During the Eisenhower administration, Winchester also formalized a sister city relationship with Ambato, Ecuador.

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 44.9% 4,790 | 48.4% 5,164 | 6.7% 711 |

| 2012 | 48.0% 4,946 | 49.5% 5,094 | 2.5% 256 |

| 2008 | 46.7% 4,725 | 52.0% 5,268 | 1.3% 133 |

| 2004 | 56.6% 5,283 | 42.5% 3,967 | 1.0% 93 |

| 2000 | 54.7% 4,314 | 42.1% 3,318 | 3.2% 254 |

| 1996 | 51.0% 3,681 | 41.9% 3,027 | 7.1% 514 |

| 1992 | 49.8% 3,833 | 35.9% 2,768 | 14.3% 1,100 |

| 1988 | 65.5% 4,497 | 33.5% 2,300 | 1.0% 65 |

| 1984 | 70.7% 5,055 | 28.9% 2,064 | 0.5% 33 |

| 1980 | 64.0% 4,240 | 30.3% 2,006 | 5.7% 377 |

| 1976 | 62.9% 4,075 | 36.2% 2,346 | 1.0% 63 |

| 1972 | 75.6% 4,647 | 23.1% 1,418 | 1.4% 86 |

| 1968 | 55.8% 2,695 | 28.1% 1,360 | 16.1% 778 |

| 1964 | 49.1% 2,180 | 50.8% 2,254 | 0.1% 3 |

| 1960 | 65.6% 2,326 | 33.9% 1,203 | 0.5% 16 |

| 1956 | 69.5% 2,375 | 27.6% 945 | 2.9% 99 |

| 1952 | 69.2% 2,375 | 30.7% 1,055 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1948 | 50.0% 1,272 | 35.1% 894 | 14.9% 380 |

| 1944 | 52.1% 1,095 | 47.6% 1,000 | 0.3% 7 |

| 1940 | 45.7% 945 | 53.9% 1,114 | 0.4% 8 |

| 1936 | 40.1% 743 | 59.2% 1,096 | 0.7% 12 |

| 1932 | 36.5% 698 | 61.7% 1,179 | 1.7% 33 |

| 1928 | 59.5% 1,168 | 40.5% 794 | |

| 1924 | 33.4% 420 | 65.2% 820 | 1.4% 18 |

| 1920 | 41.5% 540 | 56.6% 736 | 1.9% 24 |

| 1916 | 28.7% 196 | 68.4% 468 | 2.9% 20 |

| 1912 | 20.8% 141 | 66.0% 447 | 13.2% 89 |

References

- ↑ "Meet the Mayor". City of Winchester. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Population estimates, July 1, 2015, (V2015)". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-21.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Carrie Hunter Willis and Etta Belle Walker, 1937, Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, p. 16-17.

- ↑ Joseph Doddridge, A History of the Valley of Virginia, 1850, p. 44

- ↑ David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989

- ↑ Joseph Doddridge, A History of the Valley of Virginia, 1850, p. 40.

- 1 2 Lee, Marge (2003). The Gardens of Glen Burnie. The Glass-Glen Burnie Museum Inc., Winchester, VA. ISBN 978-0-9743109-0-9.

- ↑ Historical Statement Relative to the Town of Winchester

- ↑ Greene, Katherine Glass (1926). Winchester, Virginia And Its Beginnings, 1743-1814. Shenandoah Publishing House. p. 32. ISBN 9780788420627.

- ↑ Official Records

- ↑ "First Military District". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ↑ Report of the Secretary of the Commonwealth to the Governor and General Assembly of Virginia. (1918).

- ↑ "Handley Regional Library". Archived from the original on April 5, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Museum of the Shenandoah Valley". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Winchester, Virginia Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Winchester, VA Monthly weather forecast". Weather Channel. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "QuickFacts - Winchester city, Virginia(County)". www.census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Winchester, Virginia". www.city-data.com. City-Data. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ "Shenandoah Apple Blossom Festival". Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ↑ "FEMA Disaster Operations Center To Be Housed At New Facility In Winchester | FEMA.gov". Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ↑ "Records Management" (Folder). Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ↑ "Middle East District > Contact". Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ↑ "Capitol Records Pressing Plant, Winchester".

- ↑ "City of Winchester, Virginia Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ended June 30, 2016" (PDF).

- ↑ "Winchester Royals". Valley Baseball League. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Valley League Baseball". Valley Baseball League. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ Melia, Tamara Moser. "John H. Aulick (ca. 1791-1873)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ↑ Shepard, Lee. "Briscoe Gerard Baldwin (1789–1852)". Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ↑ DeGering, Etta (1966). Wilderness Wife. D. McKay Co.

- ↑ "History of the Upper Ohio Valley". Brant & Fuller. 1890.

- ↑ Brown, Parker (1982). "The Battle of Sandusky: June 4-6, 1782". Retrieved September 18, 2018.

His nickname, "Auver Mike," arose from his practice of starting sentences with the word "auver" to counteract stammering.

- ↑ Caldwell, John Alexander (1880). History of Belmont and Jefferson Counties Ohio: And Incidentally Historical Collections Pertaining to Border Warfare and the Early Settlement of the Adjacent Portion of the Ohio Valley. The Historical Publishing Company. ISBN 9780832862939.

MICHAEL MYERS, SR, Was born at Winchester, Virginia, in 1845 (sic 1745)

- ↑ Hogg, J. Bernard (1936). "Presley Neville". The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 19: 17.

- ↑ Munske, Roberta R.; Kerns, Wilmer L., eds. (2004). Hampshire County, West Virginia, 1754–2004. Romney, West Virginia: The Hampshire County 250th Anniversary Committee. ISBN 978-0-9715738-2-6. OCLC 55983178. :45

- ↑ "Robert Thomas Barton". Arlis Herring.com. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ↑ "DENVER, James William - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- ↑ "Helen Hamilton Gardener," in The National Cyclopaedia of America Biography: Volume 9. New York: James T. White and Co., 1899; pg. 451.

- ↑ root. "Frederick William Mackey Holliday". www.nga.org. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "George Hay Lee, July 1, 1852-April 1861". Virginia Appellate Court History. 2014-05-02. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- ↑ "A Woman's Civil War: A Diary with Reminiscences of the War, from March 1862 (publisher's book information page)". University of Wisconsin Press. May 8, 2012. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ↑ 'Southern Writers: Anew Biographical Dictionary,' Joseph M. Flora/Amber Vogel-editors,' Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, Louisiana: 2006, Biographical Sketch of James Innes Randolph, pg. 331

- ↑ "Ann Tucker McGuire profile".

- ↑ Lingan, John (2015) "Toxically Pure". The Baffler (Number 27).

- ↑ "Brian Benben profile". Filmreference.com. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ↑ Yardley, William (30 Jul 2013). "Harry F. Byrd, Virginia Senator, Dies at 98". The New York Times.

- ↑ "William & Mary Athletics The Tribe Roster 2004".

- ↑ Hilda Hensley death record accessed 4/4/2015

- ↑ "Doug Creek". The Baseball Almanac.

- ↑ Bieter, John (2015). "Claude Dallas: The Myth Comes to Life". The Blue Review.

- ↑ Bush, John. "Penny DeHaven biography". CMT.com. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ↑ "11 Erick Green". HokieSports.com. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Devon McTavish". DC United. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ↑ "GOP Candidate Rick Santorum's Daughter Hospitalized In Virginia". CBS. January 31, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ↑ Tsukayama, Hayley (May 1, 2015). "Five ways professional gaming is like any other sport". Washington Post.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winchester, Virginia. |