Progesterone (medication)

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Prometrium, Utrogestan, Endometrin, Crinone, others |

| Synonyms | Pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604017 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

• By mouth (capsule) • Sublingual (tablet) • Topical (cream, gel) • Vaginal (capsule, tablet, gel, suppository, ring) • Rectal (suppository) • IM injection (oil solution) • SC injection (aq. soln.) • Intrauterine (IUD) |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Antimineralocorticoid; Neurosteroid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: <2.4%[2] |

| Protein binding |

98–99%:[3][4] • Albumin: 80% • CBG: 18% • SHBG: <1% • Free: 1–2% |

| Metabolism |

Mainly liver: • 5α- and 5β-reductase • 3α- and 3β-HSD • 20α- and 20β-HSD • Conjugation • 17α-Hydroxylase • 21-Hydroxylase • CYPs (e.g., CYP3A4) |

| Metabolites |

• Dihydroprogesterones • Pregnanolones • Pregnanediols • 20α-Hydroxyprogesterone • 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone • Pregnanetriols • 11-Deoxycorticosterone (And glucuronide/sulfate conjugates) |

| Elimination half-life |

• Oral: 5 hours (with food)[5] * Sublingual: 6–7 hours[6] • Vaginal: 14–50 hours[7][6] • Topical: 30–40 hours[8] • IM: 20–28 hours[9][7][10] • SC: 13–18 hours[10] • IV: 3–90 minutes[11] |

| Excretion | Bile and urine[12][13] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.469 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Specific rotation | [α]D |

| Melting point | 126 °C (259 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Progesterone is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone.[14] It is a progestogen and is used in combination with estrogens mainly in hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms and low sex hormone levels in women.[14][15] It is also used in women to support pregnancy and fertility and to treat gynecological disorders.[16][17][18][19] Progesterone can be taken by mouth, in through the vagina, and by injection into muscle or fat, among other routes.[14] A progesterone vaginal ring and progesterone intrauterine device used for birth control also exist in some areas of the world.[20][21]

Progesterone is well-tolerated and often produces few or no side effects.[22] However, a number of side effects are possible, for instance mood changes.[22] If progesterone is taken by mouth or at high doses, certain central side effects including sedation, sleepiness, and cognitive impairment can also occur.[22][14] The drug is a naturally occurring progestogen and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor (PR), the biological target of progestogens like endogenous progesterone.[14] It opposes the effects of estrogens in various parts of the body like the uterus and also blocks the effects of the hormone aldosterone.[14][23] In addition, progesterone has neurosteroid effects in the brain.[14]

Progesterone was first isolated in pure form in 1934.[24][25] It first became available as a medication later that year.[26][27] Oral micronized progesterone (OMP), which allowed progesterone to be taken by mouth, was introduced in 1980.[27][16][28] A large number of synthetic progestogens, or progestins, have been derived from progesterone and are used as medications as well.[14] Examples include medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone.[14]

Medical uses

Hormone therapy

Menopause

Progesterone is used in combination with an estrogen as a component of menopausal hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[14] A progestogen is needed to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and increased risk of endometrial cancer caused by unopposed estrogens in women who have intact uteruses.[14] In addition, progestogens, including progesterone, are able to treat and improve hot flashes.[14] Progesterone, both alone and in combination with an estrogen, also has beneficial effects on skin health and is able to slow the rate of skin aging in postmenopausal women.[29][30]

Based on animal research, progesterone may be involved in sexual function in women.[31][32] However, very limited clinical research suggests that progesterone does not improve sexual desire or function in women.[33]

Transgender women

Progesterone is used as a component of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women in combination with estrogens and antiandrogens.[34][15] However, the addition of progestogens to HRT for transgender women is controversial and their role is unclear.[34][15] Some patients and clinicians believe anecdotally that progesterone may enhance breast development, improve mood, and increase sex drive.[15] However, there is a lack of evidence from well-designed studies to support these notions at present.[15] In addition, progestogens can produce undesirable side effects, although bioidentical progesterone may be safer and better tolerated than synthetic progestogens like medroxyprogesterone acetate.[34][35]

Because some believe that progestogens are necessary for full breast development, progesterone is sometimes used in transgender women with the intention of enhancing breast development.[34][36][35] However, a 2014 review concluded the following on the topic of progesterone for enhancing breast development in transgender women:[36]

- "Our knowledge concerning the natural history and effects of different cross-sex hormone therapies on breast development in [transgender] women is extremely sparse and based on low quality of evidence. Current evidence does not provide evidence that progestogens enhance breast development in [transgender] women. Neither do they prove the absence of such an effect. This prevents us from drawing any firm conclusion at this moment and demonstrates the need for further research to clarify these important clinical questions."[36]

While the influence of progesterone on breast development is uncertain, it is known that progesterone can cause temporary breast enlargement due to local fluid retention in the breasts, and this may give a misleading appearance of breast growth.[37][38] Aside from a hypothetical involvement in breast development, progestogens are not otherwise known to be involved in physical feminization.[35][34]

Pregnancy support

Vaginally dosed progesterone is being investigated as potentially beneficial in preventing preterm birth in women at risk for preterm birth. The initial study by Fonseca suggested that vaginal progesterone could prevent preterm birth in women with a history of preterm birth.[39] According to a recent study, women with a short cervix that received hormonal treatment with a progesterone gel had their risk of prematurely giving birth reduced. The hormone treatment was administered vaginally every day during the second half of a pregnancy.[40] A subsequent and larger study showed that vaginal progesterone was no better than placebo in preventing recurrent preterm birth in women with a history of a previous preterm birth,[41] but a planned secondary analysis of the data in this trial showed that women with a short cervix at baseline in the trial had benefit in two ways: a reduction in births less than 32 weeks and a reduction in both the frequency and the time their babies were in intensive care.[42]

In another trial, vaginal progesterone was shown to be better than placebo in reducing preterm birth prior to 34 weeks in women with an extremely short cervix at baseline.[43] An editorial by Roberto Romero discusses the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment.[44] A meta-analysis published in 2011 found that vaginal progesterone cut the risk of premature births by 42 percent in women with short cervixes.[45] The meta-analysis, which pooled published results of five large clinical trials, also found that the treatment cut the rate of breathing problems and reduced the need for placing a baby on a ventilator.[46]

Fertility support

Progesterone is used for luteal support in assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles such as in vitro fertilization (IVF).[18][47] It is also used to correct luteal phase deficiency to prepare the endometrium for implantation in infertility therapy and is used to support early pregnancy.[48][49]

Birth control

A progesterone vaginal ring is available for birth control when breastfeeding in a number of areas of the world.[20] An intrauterine device containing progesterone has also been marketed under the brand name Progestasert for birth control, including previously in the United States.[50]

Gynecological disorders

Progesterone is used to control persistent anovulatory bleeding.[51][52][53] It is used in non-pregnant women with a delayed menstruation of one or more weeks, in order to allow the thickened endometrial lining to slough off. This process is termed a progesterone withdrawal bleed. Progesterone is taken orally for a short time (usually one week), after which it is discontinued and bleeding should occur.

Other uses

Breast pain

Progesterone is approved under the brand name Progestogel as a 1% topical gel for local application to the breasts to treat breast pain in certain countries.[54][55][56] It is not approved for systemic therapy.[57][54] It has been found in clinical studies to inhibit estrogen-induced proliferation of breast epithelial cells and to abolish breast pain and tenderness in women with the condition.[56]

Premenstrual syndrome

Historically, progesterone has been widely used in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome.[58] A 2012 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence for or against the effectiveness of progesterone for this indication.[59] Another review of 10 studies found that progesterone was not effective for this condition, although it stated that insufficient evidence is available currently to make a definitive statement on progesterone in premenstrual syndrome.[58][60]

Catamenial epilepsy

Progesterone can be used to treat catamenial epilepsy by supplementation during certain periods of the menstrual cycle.[61]

Available forms

Progesterone is available in a variety of different forms, including oral capsules, sublingual tablets, vaginal capsules, tablets, gels, suppositories, and rings; rectal suppositories; oil solutions for intramuscular injection; and aqueous solutions for subcutaneous injection.[62][14] A 1% topical progesterone gel is approved for local application to the breasts to treat breast pain, but is not indicated for systemic therapy.[57][54] Progesterone was previously available as an intrauterine device for use in hormonal contraception, but this formulation was discontinued.[62] Progesterone is also limitedly available in combination with estrogens such as estradiol and estradiol benzoate for use by intramuscular injection.[63][64]

In addition to approved pharmaceutical products, progesterone is available in unregulated custom compounded and over-the-counter formulations like systemic transdermal creams and other preparations.[65][66][67][68][69] The systemic efficacy of transdermal/topical progesterone is controversial and has not been demonstrated.[67][68][69]

| Route | Form | Dose | Brand names | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Capsules | 100, 200, 300 mg | Prometrium, Utrogestan, Microgest | ||

| Sublingual | Tablets | 50, 100 mg | Luteina | ||

| Topicala | Gel | 1% | Progestogel | ||

| Vaginal | Capsules | 100, 200 mg | Utrogestan | ||

| Vaginal | Tablets | 100 mg | Endometrin, Lutinus | ||

| Vaginal | Gel | 4%, 8% (45, 90 mg) | Crinone, Crinone 8%, Prochieve | ||

| Vaginal | Suppositories | 200, 400 mg | Cyclogest | ||

| Vaginal | Rings | 10 mg/day for 3 months | Fertiring, Progering | ||

| Rectal | Suppositories | 200, 400 mg | Cyclogest | ||

| Intramuscularb | Vials | 10, 25, 50, 100 mg/mL | Progesterone, Progestaject, Gestone, Strone | ||

| Subcutaneousb | Vials | 25 mg/vial | Prolutex | ||

| Intrauterine | IUD | 38 mg | Progestasert | ||

| a = For application to the breasts. b = Injection. Note 1: This table does not include combination products, such as progesterone in combination with estrogens. Note 2: Some of these formulations have been marketed previously but may no longer be available. Note 3: The availability of pharmaceutical progesterone products differs by country (see the Availability section of this article). Note 4: This table does not include compounded progesterone products. Sources:[62][70][71][72][73][74] | |||||

Contraindications

Contraindications of progesterone include hypersensitivity to progesterone or progestogens, prevention of cardiovascular disease (a Black Box warning), thrombophlebitis, thromboembolic disorder, cerebral hemorrhage, impaired liver function or disease, breast cancer, reproductive organ cancers, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, missed menstruations, miscarriage, or a history of these conditions.[75][76] Progesterone should be used with caution in people with conditions that may be adversely affected by fluid retention such as epilepsy, migraine headaches, asthma, cardiac dysfunction, and renal dysfunction.[75][76] It should also be used with caution in patients with anemia, diabetes mellitus, a history of depression, previous ectopic pregnancy, venereal disease, and unresolved abnormal Pap smear.[75][76] Use of progesterone is not recommended during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[76] However, the drug has been deemed usually safe in breastfeeding by the American Academy of Pediatrics, but should not be used during the first four months of pregnancy.[75] Some progesterone formulations contain benzyl alcohol, and this may cause a potentially fatal "gasping syndrome" if given to premature infants.[75]

Side effects

Progesterone is well-tolerated and many clinical studies have reported no side effects.[22] Side effects of progesterone may include abdominal cramps, back pain, breast tenderness, constipation, nausea, dizziness, edema, vaginal bleeding, hypotension, fatigue, dysphoria, depression, and irritability.[22] Side effects including drowsiness, sedation, sleepiness, fatigue, sluggishness, reduced vigor, dizziness, lightheadedness, decreased mental acuity, confusion, and cognitive, memory, and/or motor impairment may occur with oral ingestion and/or at high doses of progesterone, and are due to progesterone's neurosteroid metabolites (namely allopregnanolone).[22][77][78] The same may be true for side effects of progesterone including dysphoria, depression, anxiety, and irritability, and both the adverse cognitive/sedative and emotional side effects of progesterone may be reduced or avoided by parenteral routes of administration such as vaginal or intramuscular injection.[10][79] Also, progesterone may be taken before bed to avoid these side effects and/or to help with sleep.[77]

Vaginal progesterone may be associated with vaginal irritation, itchiness, and discharge, decreased libido, painful sexual intercourse, vaginal bleeding or spotting in association with cramps, and local warmth or a "feeling of coolness" without discharge.[22] Intramuscular injection may cause mild-to-moderate pain at the site of injection.[22] High intramuscular doses of progesterone have been associated with increased body temperature, which may be alleviated with paracetamol treatment.[22]

Unlike various progestins, progesterone lacks off-target hormonal side effects caused by, for instance, androgenic, antiandrogenic, glucocorticoid, or estrogenic activity.[14] Conversely, it can still produce side effects related to its antimineralocorticoid and neurosteroid activity.[14] The neurosteroid side effects of progesterone are notably not shared with progestins and hence are unique to progesterone.[14] Compared to the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate, there are fewer reports of breast tenderness with progesterone, and the magnitude and duration of vaginal bleeding with progesterone is reported to be lower.[22]

Long-term effects

The combination of an estrogen and progesterone has not been found to increase the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.[80][81][82][83] In contrast, all assessed progestins except the atypical progestin dydrogesterone have been associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer when used in combination with an estrogen in menopausal hormone therapy.[80][82][81][83] On the other hand, progesterone is associated with a significantly increased risk of endometrial cancer in combination with an estrogen, while this is not true with any progestin.[84][83] However, this does not appear to be the case with vaginal progesterone, which achieves high local concentrations of progesterone in the uterus that are likely fully sufficient for endometrial protection.[84] Whereas the combination of an estrogen and a progestin is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism relative to estrogen alone, there is no further increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism with the combination of an estrogen and progesterone relative to estrogen only.[84] The reasons for these differences between progesterone and progestins is not entirely clear, but may be due to the relatively low potency of oral progesterone and a potentially inadequate progestogenic effect of this medication.[84][83]

Overdose

Progesterone is likely to be relatively safe in overdose. Levels of progesterone during pregnancy are up to 100-fold higher than during normal menstrual cycling, although levels increase gradually over the course of pregnancy.[85] Oral dosages of progesterone of as high as 3,600 mg/day have been assessed in clinical trials, with the main side effect being sedation.[86] There is a case report of progesterone misuse with an oral dosage of 6,400 mg per day.[87] Administration of as much as 1,000 mg progesterone by intramuscular injection in humans was uneventful in terms of toxicity, but did induce extreme sedation and somnolence accompanied by nearly unarousable sleep, though the individuals were still able to be awakened with sufficient physical stimulation.[88]

Interactions

There are several notable drug interactions with progesterone. Certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline may increase the GABAA receptor-related central depressant effects of progesterone by enhancing its conversion into 5α-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone via activation of 3α-HSD.[89] Progesterone potentiates the sedative effects of benzodiazepines and alcohol.[90] Notably, there is a case report of progesterone abuse alone with very high doses.[91] 5α-Reductase inhibitors such as finasteride and dutasteride inhibit the conversion of progesterone into the inhibitory neurosteroid allopregnanolone, and for this reason, may have the potential to reduce the sedative and related effects of progesterone.[92][93][94]

Progesterone is a weak but significant agonist of the pregnane X receptor (PXR), and has been found to induce several hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as CYP3A4, especially when concentrations are high, such as with pregnancy range levels.[95][96][97][98] As such, progesterone may have the potential to accelerate the metabolism of various drugs.[95][96][97][98]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Progesterone is a progestogen, or an agonist of the nuclear progesterone receptors (PRs), the PR-A, PR-B, and PR-C.[14] In addition, progesterone is an agonist of the membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs), including the mPRα, mPRβ, mPRγ, mPRδ, and mPRϵ.[99][100] Aside from the PRs and mPRs, progesterone is a potent antimineralocorticoid, or antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor, the biological target of the mineralocorticoid aldosterone.[101][102] In addition to its activity as a steroid hormone, progesterone is a neurosteroid.[103] Among other neurosteroid activities, and via its active metabolites allopregnanolone and pregnanolone, progesterone is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor, the major signaling receptor of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[104]

The PRs are expressed widely throughout the body, including in the uterus, cervix, vagina, fallopian tubes, breasts, fat, skin, pituitary gland, hypothalamus, and in other areas of the brain.[14][105] In accordance, progesterone has numerous effects throughout the body.[14] Among other effects, progesterone produces changes in the female reproductive system, the breasts, and the brain.[14][105] Progesterone has functional antiestrogenic effects due to its progestogenic activity, including in the uterus, cervix, and vagina.[14] The effects of progesterone may influence health in both positive and negative ways.[14] In addition to the aforementioned effects, progesterone has antigonadotropic effects due to its progestogenic activity, and can inhibit ovulation and suppress gonadal sex hormone production.[14]

The activities of progesterone besides those mediated by the PRs and mPRs are also of significance.[14] Progesterone lowers blood pressure and reduces water and salt retention among other effects via its antimineralocorticoid activity.[14][106] In addition, progesterone can produce sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic, euphoric, cognitive-, memory-, and motor-impairing, anticonvulsant, and even anesthetic effects via formation of sufficiently high concentrations of its neurosteroid metabolites and consequent GABAA receptor potentiation in the brain.[22][77][78][107]

There are differences between progesterone and other progestogens, such as progestins like medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone, with implications for pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics as well as efficacy, tolerability, and safety.[14]

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of progesterone are dependent on its route of administration. The drug is approved in the form of oil-filled capsules containing micronized progesterone for oral administration, termed oral micronized progesterone or OMP.[108] It is also available in the form of vaginal or rectal suppositories or pessaries, topical creams and gels,[109] oil solutions for intramuscular injection, and aqueous solutions for subcutaneous injection.[108][10][110]

Routes of administration that progesterone has been used by include oral, intranasal, transdermal/topical, vaginal, rectal, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intravenous injection.[10] Vaginal progesterone is available in the form of progesterone capsules, tablets or inserts, gels, suppositories or pessaries, and rings.[10]

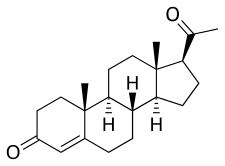

Chemistry

Progesterone is a naturally occurring pregnane steroid and is also known as pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione.[111][112] It has a double bond (4-ene) between the C4 and C5 positions and two ketone groups (3,20-dione), one at the C3 position and the other at the C20 position.[111][112] Due to its pregnane core and C4(5) double bond, progesterone is often abbreviated as P4. It is contrasted with pregnenolone, which has a C5(6) double bond and is often abbreviated as P5.

Derivatives

A large number of progestins, or synthetic progestogens, have been derived from progesterone.[111][14] They can be categorized into several structural groups, including derivatives of retroprogesterone, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, 17α-methylprogesterone, and 19-norprogesterone, with a respective example from each group including dydrogesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, medrogestone, and promegestone.[14] The progesterone ethers quingestrone (progesterone 3-cyclopentyl enol ether) and progesterone 3-acetyl enol ether are among the only examples that do not belong to any of these groups.[105][113] Another major group of progestins, the 19-nortestosterone derivatives, exemplified by norethisterone (norethindrone) and levonorgestrel, are not derived from progesterone but rather from testosterone.[14]

A variety of synthetic inhibitory neurosteroids have been derived from progesterone and its neurosteroid metabolites, allopregnanolone and pregnanolone.[111] Examples include alfadolone, alfaxolone, ganaxolone, hydroxydione, minaxolone, and renanolone.[111] In addition, C3 and C20 conjugates of progesterone, such as progesterone carboxymethyloxime (progesterone 3-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime; P4-3-CMO), P1-185 (progesterone 3-O-(L-valine)-E-oxime), EIDD-1723 (progesterone 20E-[O-[(phosphonooxy)methyl]oxime] sodium salt), EIDD-036 (progesterone 20-oxime; P4-20-O), and VOLT-02 (chemical structure unreleased), have been developed as water-soluble prodrugs of progesterone and neurosteroids.[114][115][116][117][118][119]

Synthesis

Chemical syntheses of progesterone have been published.[120]

History

The hormonal action of progesterone was discovered in 1929.[24][25][121] Pure crystalline progesterone was isolated in 1934 and its chemical structure was determined.[24][25] Later that year, chemical synthesis of progesterone was accomplished.[25][122] Shortly following its chemical synthesis, progesterone began being tested clinically in women.[25] In 1934, Schering introduced progesterone as a pharmaceutical drug under the brand name Proluton.[26][27] It was administered by intramuscular injection because it is rapidly metabolized when taken by mouth and hence required very high oral doses to produce effects.[16][123]

It was not until almost half a century later that a non-injected formulation of progesterone was marketed.[73] Micronization, similarly to the case of estradiol, allowed progesterone to be absorbed effectively via other routes of administration, but the micronization process was difficult for manufacturers for many years.[124] OMP was finally marketed in France under the brand name Utrogestan in 1980,[27][16][28] and this was followed by the introduction of OMP in the United States under the brand name Prometrium in 1998.[124] In the early 1990s, vaginal micronized progesterone (brand names Crinone, Utrogestan, Endometrin)[125] was also marketed.[73]

Progesterone was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as a vaginal gel on 31 July 1997,[126] a capsule to be taken by mouth on 14 May 1998,[127] in an injection form on 25 April 2001,[128] and as a vaginal insert on 21 June 2007.[129]

Society and culture

Generic names

Progesterone is the generic name of the drug in English and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCIT, and JAN, while progestérone is its name in French and its DCF.[63][111][112][130] It is also referred to as progesteronum in Latin, progesterona in Spanish and Portuguese, and progesteron in German.[63][112]

Brand names

Progesterone is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[63][112] Examples of major brand names under which progesterone has been marketed include Crinone, Crinone 8%, Cyclogest, Endogest, Endometrin, Geslutin, Gesterol, Gestone, Luteina, Luteinol, Lutigest, Lutinus, Microgest, Progeffik, Progelan, Progendo, Progering, Progest, Progestaject, Progestan, Progesterone, Progestin, Progestogel, Prolutex, Proluton, Prometrium, Prontogest, Strone, Susten, Utrogest, and Utrogestan.[63][112]

Availability

Progesterone is widely available in countries throughout the world in a variety of formulations.[63][64] Progesterone in the form of oral capsules; vaginal capsules, tablets/inserts, and gels; and intramuscular oil have widespread availability.[63][64] The following formulations/routes of progesterone have selective or more limited availability:[63][64]

- A tablet of micronized progesterone which is marketed under the brand name Luteina is indicated for sublingual administration in addition to vaginal administration and is available in Poland and Ukraine.[63][64]

- A progesterone suppository which is marketed under the brand name Cyclogest is indicated for rectal administration in addition to vaginal administration and is available in Cyprus, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Malta, Oman, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam.[63][64]

- An aqueous solution of progesterone complexed with β-cyclodextrin for subcutaneous injection is marketed under the brand name Prolutex in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, and Switzerland.[63][64]

- A non-systemic topical gel formulation of progesterone for local application to the breasts to treat breast pain is marketed under the brand name Progestogel and is available in Belgium, Bulgaria, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Georgia, Germany, Hong Kong, Lebanon, Peru, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Switzerland, Tunisia, Venezuela, and Vietnam.[63][64] It was also formerly available in Italy, Portugal, and Spain, but was discontinued in these countries.[64]

- A progesterone intrauterine device was previously marketed under the brand name Progestasert and was available in Canada, France, the United States, and possibly other countries, but was discontinued.[64][131]

- Progesterone vaginal rings are marketed under the brand names Fertiring and Progering and are available in Chile, Ecuador, and Peru.[63][64]

In addition to single-drug formulations, the following progesterone combination formulations are or have been marketed, albeit with limited availability:[63][64]

- A combination pack of progesterone capsules for oral use and estradiol gel for transdermal use is marketed under the brand name Estrogel Propak in Canada.[63][64]

- A combination pack of progesterone capsules and estradiol tablets for oral use is marketed in an under the brand name Duogestan in Belgium.[63][64]

- Progesterone and estradiol in an aqueous suspension for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Cristerona FP in Argentina.[63][64]

- Progesterone and estradiol in microspheres in an oil solution for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Juvenum in Mexico.[63][64][132]

- Progesterone and estradiol benzoate in an oil solution for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand names Duogynon, Duoton Fort T P, Emmenovis, Gestrygen, Lutofolone, Menovis, Mestrolar, Metrigen Fuerte, Nomestrol, Phenokinon-F, Prodiol, Pro-Estramon-S, Proger F, Progestediol, and Vermagest and is available in Belize, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Honduras, Italy, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Taiwan, Thailand, and Turkey.[63][64]

- Progesterone and estradiol hemisuccinate in an oil solution for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Hosterona in Argentina.[63][64]

- Progesterone and estrone for use by intramuscular injection is marketed under the brand name Synergon in Monaco.[63]

United States

As of November 2016, progesterone is available in the United States in the following formulations:[62]

- Oral: Capsules: Prometrium (100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg)

- Vaginal: Tablets: Endometrin (100 mg); Gels: Crinone (4%, 8%)

- Intramuscular injection: Oil: Progesterone (50 mg/mL)

A 25 mg/mL concentration of progesterone oil for intramuscular injection and a 38 mg/device progesterone intrauterine device (Progestasert) have been discontinued.[62]

An oral combination formulation of micronized progesterone and estradiol in oil-filled capsules (developmental code name TX-001HR) is currently under development in the United States for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and endometrial hyperplasia, though it has yet to be approved or introduced.[133][5]

Progesterone is also available in unregulated custom preparations from compounding pharmacies in the United States.[65][66] In addition, transdermal progesterone is available over-the-counter in the United States, although the clinical efficacy of transdermal progesterone is controversial.[67][68][69]

Research

Due to its neurosteroid actions, progesterone has been researched for the potential treatment of a number of central nervous system conditions such as multiple sclerosis, brain damage, and drug addiction. Additional uses of progesterone may include treatment of hypertension (due to its antimineralocorticoid activity), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and benzodiazepine withdrawal (due to its neurosteroid actions).[22]

Multiple sclerosis

Progesterone is being investigated as potentially beneficial in treating multiple sclerosis, since the characteristic deterioration of nerve myelin insulation halts during pregnancy, when progesterone levels are raised; deterioration commences again when the levels drop.

Brain damage

Studies as far back as 1987 show that female sex hormones have an effect on the recovery of traumatic brain injury.[134] In these studies, it was first observed that pseudopregnant female rats had reduced edema after traumatic brain injury. Recent clinical trials have shown that among patients that have suffered moderate traumatic brain injury, those that have been treated with progesterone are more likely to have a better outcome than those who have not.[135] A number of additional animal studies have confirmed that progesterone has neuroprotective effects when administered shortly after traumatic brain injury.[136] Encouraging results have also been reported in human clinical trials.[137][138]

Combination treatments

Vitamin D and progesterone separately have neuroprotective effects after traumatic brain injury, but when combined their effects are synergistic.[139] When used at their optimal respective concentrations, the two combined have been shown to reduce cell death more than when alone.

One study looks at a combination of progesterone with estrogen. Both progesterone and estrogen are known to have antioxidant-like qualities and are shown to reduce edema without injuring the blood-brain barrier. In this study, when the two hormones are administered alone it does reduce edema, but the combination of the two increases the water content, thereby increasing edema.[140]

Clinical trials

The clinical trials for progesterone as a treatment for traumatic brain injury have only recently begun. ProTECT, a phase II trial conducted in Atlanta at Grady Memorial Hospital in 2007, the first to show that progesterone reduces edema in humans. Since then, trials have moved on to phase III. The National Institute of Health began conducting a nationwide phase III trial in 2011 led by Emory University.[135] A global phase III initiative called SyNAPSe®, initiated in June 2010, is run by a United States-based private pharmaceutical company, BHR Pharma, and is being conducted in the United States, Argentina, Europe, Israel and Asia.[141][142] Approximately 1,200 patients with severe (Glasgow Coma Scale scores of 3-8), closed-head TBI will be enrolled in the study at nearly 150 medical centers.

Addiction

To examine the effects of progesterone on nicotine addiction, participants in one study were either treated orally with a progesterone treatment, or treated with a placebo. When treated with progesterone, participants exhibited enhanced suppression of smoking urges, reported higher ratings of “bad effects” from IV nicotine, and reported lower ratings of “drug liking”. These results suggest that progesterone not only alters the subjective effects of nicotine, but reduces the urge to smoke cigarettes.[143]

See also

References

- ↑ Adler N, Pfaff D, Goy RW (6 Dec 2012). Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology Volume 7 Reproduction (1st ed.). New York: Plenum Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-4684-4834-4. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ Levine H, Watson N (March 2000). "Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of Crinone 8% administered vaginally versus Prometrium administered orally in postmenopausal women(3)". Fertil. Steril. 73 (3): 516–21. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00553-1. PMID 10689005.

- ↑ Fritz MA, Speroff L (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

- ↑ Marshall WJ, Marshall WJ, Bangert SK (2008). Clinical Chemistry. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 192–. ISBN 0-7234-3455-7.

- 1 2 Pickar JH, Bon C, Amadio JM, Mirkin S, Bernick B (December 2015). "Pharmacokinetics of the first combination 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule in clinical development for menopausal hormone therapy". Menopause. 22 (12): 1308–16. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000467. PMC 4666011. PMID 25944519.

- 1 2 Хомяк, Н. В., Мамчур, В. И., & Хомяк, Е. В. (2014). Клинико-фармакологические особенности современных лекарственных форм микронизированного прогестерона, применяющихся во время беременности. Здоровье, (4), 90. http://health-ua.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/MAZG2-2015_28-35.pdf

- 1 2 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/020701s026lbl.pdf

- ↑ Mircioiu C, Perju A, Griu E, Calin G, Neagu A, Enachescu D, Miron DS (1998). "Pharmacokinetics of progesterone in postmenopausal women: 2. Pharmacokinetics following percutaneous administration". Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 23 (3): 397–402. PMID 9842983.

- ↑ Simon JA, Robinson DE, Andrews MC, Hildebrand JR, Rocci ML, Blake RE, Hodgen GD (1993). "The absorption of oral micronized progesterone: the effect of food, dose proportionality, and comparison with intramuscular progesterone". Fertil. Steril. 60 (1): 26–33. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56031-2. PMID 8513955.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cometti B (November 2015). "Pharmaceutical and clinical development of a novel progesterone formulation". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 94 Suppl 161: 28–37. doi:10.1111/aogs.12765. PMID 26342177.

The administration of progesterone in injectable or vaginal form is more efficient than by the oral route, since it avoids the metabolic losses of progesterone encountered with oral administration resulting from the hepatic first-pass effect (32). In addition, the injectable forms avoid the need for higher doses that cause a fairly large number of side-effects, such as somnolence, sedation, anxiety, irritability and depression (33).

- ↑ Aufrère MB, Benson H (June 1976). "Progesterone: an overview and recent advances". J Pharm Sci. 65 (6): 783–800. doi:10.1002/jps.2600650602. PMID 945344.

- ↑ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/1998/20843lbl.pdf

- ↑ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/017362s104lbl.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wesp LM, Deutsch MB (2017). "Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 40 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. PMID 28159148.

- 1 2 3 4 Ruan X, Mueck AO (November 2014). "Systemic progesterone therapy--oral, vaginal, injections and even transdermal?". Maturitas. 79 (3): 248–55. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.009. PMID 25113944.

- ↑ Filicori M (2015). "Clinical roles and applications of progesterone in reproductive medicine: an overview". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 94 Suppl 161: 3–7. doi:10.1111/aogs.12791. PMID 26443945.

- 1 2 Ciampaglia W, Cognigni GE (2015). "Clinical use of progesterone in infertility and assisted reproduction". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 94 Suppl 161: 17–27. doi:10.1111/aogs.12770. PMID 26345161.

- ↑ Choi SJ (2017). "Use of progesterone supplement therapy for prevention of preterm birth: review of literatures". Obstet Gynecol Sci. 60 (5): 405–420. doi:10.5468/ogs.2017.60.5.405. PMC 5621069. PMID 28989916.

- 1 2 Whitaker, Amy; Gilliam, Melissa (2014). Contraception for Adolescent and Young Adult Women. Springer. p. 98. ISBN 9781461465799.

- ↑ Chaudhuri (2007). Practice Of Fertility Control: A Comprehensive Manual (7Th Edition). Elsevier India. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-81-312-1150-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Goletiani NV, Keith DR, Gorsky SJ (2007). "Progesterone: review of safety for clinical studies" (PDF). Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 15 (5): 427–44. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.427. PMID 17924777.

- ↑ Stute P, Neulen J, Wildt L (2016). "The impact of micronized progesterone on the endometrium: a systematic review". Climacteric. 19 (4): 316–28. doi:10.1080/13697137.2016.1187123. PMID 27277331.

- 1 2 3 Josimovich J (11 November 2013). Gynecologic Endocrinology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 9, 25–29, 139. ISBN 978-1-4613-2157-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coutinho EM, Segal SJ (1999). Is Menstruation Obsolete?. Oxford University Press. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-19-513021-8.

- 1 2 Seaman B (4 January 2011). The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth. Seven Stories Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-1-60980-062-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Simon JA (December 1995). "Micronized progesterone: vaginal and oral uses". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 38 (4): 902–14. doi:10.1097/00003081-199538040-00024. PMID 8616985.

- 1 2 Csech J, Gervais C (September 1982). "[Utrogestan]". Soins. Gynécologie, Obstétrique, Puériculture, Pédiatrie (in French) (16): 45–6. PMID 6925387.

- ↑ Raine-Fenning NJ, Brincat MP, Muscat-Baron Y (2003). "Skin aging and menopause : implications for treatment". Am J Clin Dermatol. 4 (6): 371–8. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304060-00001. PMID 12762829.

- ↑ Holzer G, Riegler E, Hönigsmann H, Farokhnia S, Schmidt JB, Schmidt B (2005). "Effects and side-effects of 2% progesterone cream on the skin of peri- and postmenopausal women: results from a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, randomized study". Br. J. Dermatol. 153 (3): 626–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06685.x. PMID 16120154.

- ↑ Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Ghoumari A, Massaad C, Robert F, El-Etr M, Akwa Y, Rajkowski K, Baulieu EE (June 2007). "Novel perspectives for progesterone in hormone replacement therapy, with special reference to the nervous system". Endocr. Rev. 28 (4): 387–439. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0050. PMID 17431228.

- ↑ Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Foy MR, Baudry M, Wang J, Finch CE, Morgan TE, Pike CJ, Mack WJ, Stanczyk FZ, Nilsen J (May 2008). "Progesterone receptors: form and function in brain". Front Neuroendocrinol. 29 (2): 313–39. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.02.001. PMC 2398769. PMID 18374402.

- ↑ Worsley R, Santoro N, Miller KK, Parish SJ, Davis SR (March 2016). "Hormones and Female Sexual Dysfunction: Beyond Estrogens and Androgens--Findings from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine". J Sex Med. 13 (3): 283–90. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.014. PMID 26944460.

- 1 2 3 4 5 World Professional Association for Transgender Health (September 2011), Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Seventh Version (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016

- 1 2 3 Randi Ettner; Stan Monstrey; Eli Coleman (20 May 2016). Principles of Transgender Medicine and Surgery. Routledge. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-1-317-51460-2.

- 1 2 3 Wierckx K, Gooren L, T'Sjoen G (2014). "Clinical review: Breast development in trans women receiving cross-sex hormones". J Sex Med. 11 (5): 1240–7. doi:10.1111/jsm.12487. PMID 24618412.

- ↑ Lee-Ellen C. Copstead-Kirkhorn; Jacquelyn L. Banasik (25 June 2014). Pathophysiology - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 660–. ISBN 978-0-323-29317-4.

Throughout the reproductive years, some women note swelling of the breast around the latter part of each menstrual cycle before the onset of menstruation. The water retention and subsequent swelling of breast tissue during this phase of the menstrual cycle are thought to be due to high levels of circulating progesterone stimulating the secretory cells of the breast.12

- ↑ Farage MA, Neill S, MacLean AB (2009). "Physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review". Obstet Gynecol Surv. 64 (1): 58–72. doi:10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181932a37. PMID 19099613.

- ↑ da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M (February 2003). "Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188 (2): 419–24. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.41. PMID 12592250.

- ↑ Harris, Gardiner (2011-05-02). "Hormone Is Said to Cut Risk of Premature Birth". New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Defranco EA, Fusey S, Soma-Pillay P, Porter K, How H, Schackis R, Eller D, Trivedi Y, Vanburen G, Khandelwal M, Trofatter K, Vidyadhari D, Vijayaraghavan J, Weeks J, Dattel B, Newton E, Chazotte C, Valenzuela G, Calda P, Bsharat M, Creasy GW (October 2007). "Progesterone vaginal gel for the reduction of recurrent preterm birth: primary results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 687–96. doi:10.1002/uog.5158. PMID 17899572.

- ↑ DeFranco EA, O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Fusey S, Soma-Pillay P, Porter K, How H, Schakis R, Eller D, Trivedi Y, Vanburen G, Khandelwal M, Trofatter K, Vidyadhari D, Vijayaraghavan J, Weeks J, Dattel B, Newton E, Chazotte C, Valenzuela G, Calda P, Bsharat M, Creasy GW (October 2007). "Vaginal progesterone is associated with a decrease in risk for early preterm birth and improved neonatal outcome in women with a short cervix: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 697–705. doi:10.1002/uog.5159. PMID 17899571.

- ↑ Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH (August 2007). "Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (5): 462–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067815. PMID 17671254.

- ↑ Romero R (October 2007). "Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 675–86. doi:10.1002/uog.5174. PMID 17899585.

- ↑ Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, Fusey S, Baxter JK, Khandelwal M, Vijayaraghavan J, Trivedi Y, Soma-Pillay P, Sambarey P, Dayal A, Potapov V, O'Brien J, Astakhov V, Yuzko O, Kinzler W, Dattel B, Sehdev H, Mazheika L, Manchulenko D, Gervasi MT, Sullivan L, Conde-Agudelo A, Phillips JA, Creasy GW (July 2011). "Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 38 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1002/uog.9017. PMC 3482512. PMID 21472815. Lay summary – WebMD.

- ↑ "Progesterone helps cut risk of pre-term birth". Women's health. msnbc.com. 2011-12-14. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- ↑ Yanushpolsky EH (March 2015). "Luteal phase support in in vitro fertilization". Semin. Reprod. Med. 33 (2): 118–27. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1545363. PMID 25734349.

- ↑ Palomba S, Santagni S, La Sala GB (November 2015). "Progesterone administration for luteal phase deficiency in human reproduction: an old or new issue?". J Ovarian Res. 8: 77. doi:10.1186/s13048-015-0205-8. PMC 4653859. PMID 26585269.

- ↑ Czyzyk A, Podfigurna A, Genazzani AR, Meczekalski B (June 2017). "The role of progesterone therapy in early pregnancy: from physiological role to therapeutic utility". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 33 (6): 421–424. doi:10.1080/09513590.2017.1291615. PMID 28277122.

- ↑ Tommaso Falcone; William W. Hurd (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 406–. ISBN 0-323-03309-1.

- ↑ Sweet MG, Schmidt-Dalton TA, Weiss PM, Madsen KP (January 2012). "Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women" (PDF). Am Fam Physician. 85 (1): 35–43. PMID 22230306.

- ↑ Hickey M, Higham JM, Fraser I (September 2012). "Progestogens with or without oestrogen for irregular uterine bleeding associated with anovulation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9): CD001895. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001895.pub3. PMID 22972055.

- ↑ Wathen PI, Henderson MC, Witz CA (March 1995). "Abnormal uterine bleeding". Med. Clin. North Am. 79 (2): 329–44. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30071-2. PMID 7877394.

- 1 2 3 van Keep P, Utian W (6 December 2012). The Premenstrual Syndrome: Proceedings of a workshop held during the Sixth International Congress of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, Berlin, September 1980. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-94-011-6255-5.

- ↑ Bińkowska, Małgorzata; Woroń, Jarosław (2015). "Progestogens in menopausal hormone therapy". Menopausal Review. 2: 134–143. doi:10.5114/pm.2015.52154. ISSN 1643-8876.

- 1 2 Ruan X, Mueck AO (2014). "Systemic progesterone therapy--oral, vaginal, injections and even transdermal?". Maturitas. 79 (3): 248–55. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.009. PMID 25113944.

- 1 2 Robert W. Shaw; David Luesley; Ash K. Monga (1 October 2010). Gynaecology E-Book: Expert Consult: Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 417–. ISBN 0-7020-4838-0.

- 1 2 Dickerson LM, Mazyck PJ, Hunter MH (2003). "Premenstrual syndrome". Am Fam Physician. 67 (8): 1743–52. PMID 12725453.

- ↑ Ford O, Lethaby A, Roberts H, Mol BW (2012). "Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD003415. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003415.pub4. PMID 22419287.

- ↑ Wyatt K, Dimmock P, Jones P, Obhrai M, O'Brien S (2001). "Efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in management of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review". BMJ. 323 (7316): 776–80. PMC 57352. PMID 11588078.

- ↑ Devinsky O, Schachter S, Pacia S (1 January 2005). Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-1-934559-08-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 https://www.drugs.com/international/progesterone.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian

- 1 2 Kaunitz AM, Kaunitz JD (2015). "Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: time for a reality check?". Menopause. 22 (9): 919–20. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000484. PMID 26035149.

- 1 2 Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH (2016). "Update on medical and regulatory issues pertaining to compounded and FDA-approved drugs, including hormone therapy". Menopause. 23 (2): 215–23. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000523. PMC 4927324. PMID 26418479.

- 1 2 3 Stanczyk FZ (2014). "Treatment of postmenopausal women with topical progesterone creams and gels: are they effective?". Climacteric. 17 Suppl 2: 8–11. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.944496. PMID 25196424.

- 1 2 3 Stanczyk FZ, Paulson RJ, Roy S (2005). "Percutaneous administration of progesterone: blood levels and endometrial protection". Menopause. 12 (2): 232–7. PMID 15772572.

- 1 2 3 Hermann AC, Nafziger AN, Victory J, Kulawy R, Rocci ML, Bertino JS (2005). "Over-the-counter progesterone cream produces significant drug exposure compared to a food and drug administration-approved oral progesterone product". J Clin Pharmacol. 45 (6): 614–9. doi:10.1177/0091270005276621. PMID 15901742.

- ↑ Jürgen Engel; Axel Kleemann; Bernhard Kutscher; Dietmar Reichert (14 May 2014). Pharmaceutical Substances, 5th Edition, 2009: Syntheses, Patents and Applications of the most relevant APIs. Thieme. pp. 1145–. ISBN 978-3-13-179275-4.

- ↑ Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 2168–. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- ↑ Anita MV; Sandhya Jain; Neerja Goel (31 July 2018). Use of Progestogens in Clinical Practice of Obstetrics and Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-93-5270-218-3.

- 1 2 3 Sauer MV (1 March 2013). Principles of Oocyte and Embryo Donation. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 7, 117–118. ISBN 978-1-4471-2392-7.

- ↑ Kay Elder; Brian Dale (2 December 2010). In-Vitro Fertilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-1-139-49285-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Diane S. Aschenbrenner; Samantha J. Venable (2009). Drug Therapy in Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1150–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6587-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Jahangir Moini (29 October 2008). Fundamental Pharmacology for Pharmacy Technicians. Cengage Learning. pp. 322–. ISBN 1-111-80040-5.

- 1 2 3 Wang-Cheng R, Neuner JM, Barnabei VM (2007). Menopause. ACP Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-930513-83-9.

- 1 2 Bergemann N, Ariecher-Rössler A (27 December 2005). Estrogen Effects in Psychiatric Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 179. ISBN 978-3-211-27063-9.

- ↑ de Ziegler D, Fanchin R (2000). "Progesterone and progestins: applications in gynecology". Steroids. 65 (10–11): 671–9. PMID 11108875.

[...] fairly low plasma levels of progesterone have been reported when the hormone is given orally, and proper assays are used. Circulating levels of progesterone and its metabolites, determined by sufficiently specific assays, after oral and vaginal administration of 100 mg of progesterone are illustrated in Fig. 4. As can be seen, when taken orally, progesterone accounts for less than 10%, whereas most of ingested progesterone is transformed to 5α-reduced metabolites. The metabolites of progesterone that bind to the GABAA receptor complex are responsible for drowsiness and other neurologic side effects. [See also Figure 4 for bar graphs of metabolites.]

- 1 2 Yang Z, Hu Y, Zhang J, Xu L, Zeng R, Kang D (February 2017). "Estradiol therapy and breast cancer risk in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 33 (2): 87–92. doi:10.1080/09513590.2016.1248932. PMID 27898258.

- 1 2 Lambrinoudaki I (2014). "Progestogens in postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer". Maturitas. 77 (4): 311–7. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.01.001. PMID 24485796.

- 1 2 Eden J (2017). "The endometrial and breast safety of menopausal hormone therapy containing micronised progesterone: A short review". Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 57 (1): 12–15. doi:10.1111/ajo.12583. PMID 28251642.

- 1 2 3 4 Kuhl H, Schneider HP (August 2013). "Progesterone--promoter or inhibitor of breast cancer". Climacteric. 16 Suppl 1: 54–68. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.768806. PMID 23336704.

- 1 2 3 4 Davey DA (March 2018). "Menopausal hormone therapy: a better and safer future". Climacteric: 1–8. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1439915. PMID 29526116.

- ↑ Tony M. Plant; Anthony J. Zeleznik (15 November 2014). Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction. Academic Press. pp. 2289, 2386. ISBN 978-0-12-397769-4.

- ↑ Schweizer E, Case WG, Garcia-Espana F, Greenblatt DJ, Rickels K (1995). "Progesterone co-administration in patients discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy: effects on withdrawal severity and taper outcome". Psychopharmacology. 117 (4): 424–9. PMID 7604143.

- ↑ Keefe DL, Sarrel P (1996). "Dependency on progesterone in woman with self-diagnosed premenstrual syndrome". Lancet. 347 (9009): 1182. PMID 8609776.

- ↑ Merryman W, Boiman R, Barnes L, Rothchild I (1954). "Progesterone anesthesia in human subjects". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 14 (12): 1567–9. doi:10.1210/jcem-14-12-1567. PMID 13211793.

- ↑ Pinna G, Agis-Balboa RC, Pibiri F, Nelson M, Guidotti A, Costa E (October 2008). "Neurosteroid biosynthesis regulates sexually dimorphic fear and aggressive behavior in mice". Neurochemical Research. 33 (10): 1990–2007. doi:10.1007/s11064-008-9718-5. PMID 18473173.

- ↑ Babalonis S, Lile JA, Martin CA, Kelly TH (June 2011). "Physiological doses of progesterone potentiate the effects of triazolam in healthy, premenopausal women". Psychopharmacology. 215 (3): 429–39. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2206-7. PMC 3137367. PMID 21350928.

- ↑ "Progesterone abuse". Reactions Weekly. Springer International Publishing. 599 (1): 9. 1996. doi:10.2165/00128415-199605990-00031. ISSN 1179-2051.

- ↑ Traish AM, Mulgaonkar A, Giordano N (June 2014). "The dark side of 5α-reductase inhibitors' therapy: sexual dysfunction, high Gleason grade prostate cancer and depression". Korean Journal of Urology. 55 (6): 367–79. doi:10.4111/kju.2014.55.6.367. PMC 4064044. PMID 24955220.

- ↑ Meyer L, Venard C, Schaeffer V, Patte-Mensah C, Mensah-Nyagan AG (April 2008). "The biological activity of 3alpha-hydroxysteroid oxido-reductase in the spinal cord regulates thermal and mechanical pain thresholds after sciatic nerve injury". Neurobiology of Disease. 30 (1): 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.001. PMID 18291663.

- ↑ Pazol K, Wilson ME, Wallen K (June 2004). "Medroxyprogesterone acetate antagonizes the effects of estrogen treatment on social and sexual behavior in female macaques". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (6): 2998–3006. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-032086. PMC 1440328. PMID 15181090.

- 1 2 Choi SY, Koh KH, Jeong H (February 2013). "Isoform-specific regulation of cytochromes P450 expression by estradiol and progesterone". Drug Metab. Dispos. 41 (2): 263–9. doi:10.1124/dmd.112.046276. PMC 3558868. PMID 22837389.

- 1 2 Meanwell NA (8 December 2014). Tactics in Contemporary Drug Design. Springer. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-3-642-55041-6.

- 1 2 Legato MJ, Bilezikian JP (2004). Principles of Gender-specific Medicine. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-12-440906-4.

- 1 2 Lemke TL, Williams DA (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- ↑ Soltysik K, Czekaj P (April 2013). "Membrane estrogen receptors - is it an alternative way of estrogen action?". J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 64 (2): 129–42. PMID 23756388.

- ↑ Prossnitz ER, Barton M (May 2014). "Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 389 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. PMC 4040308. PMID 24530924.

- ↑ Rupprecht R, Reul JM, van Steensel B, Spengler D, Söder M, Berning B, Holsboer F, Damm K (October 1993). "Pharmacological and functional characterization of human mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor ligands". European Journal of Pharmacology. 247 (2): 145–54. doi:10.1016/0922-4106(93)90072-H. PMID 8282004.

- ↑ Elger W, Beier S, Pollow K, Garfield R, Shi SQ, Hillisch A (2003). "Conception and pharmacodynamic profile of drospirenone". Steroids. 68 (10–13): 891–905. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2003.08.008. PMID 14667981.

- ↑ Baulieu E, Schumacher M (2000). "Progesterone as a neuroactive neurosteroid, with special reference to the effect of progesterone on myelination". Steroids. 65 (10–11): 605–12. doi:10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00173-2. PMID 11108866.

- ↑ Paul SM, Purdy RH (March 1992). "Neuroactive steroids". FASEB Journal. 6 (6): 2311–22. PMID 1347506.

- 1 2 3 P. J. Bentley (1980). Endocrine Pharmacology: Physiological Basis and Therapeutic Applications. CUP Archive. pp. 264, 274. ISBN 978-0-521-22673-8.

- ↑ Oelkers W (2000). "Drospirenone--a new progestogen with antimineralocorticoid activity, resembling natural progesterone". Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 5 Suppl 3: 17–24. PMID 11246598.

- ↑ Bäckström T, Bixo M, Johansson M, Nyberg S, Ossewaarde L, Ragagnin G, Savic I, Strömberg J, Timby E, van Broekhoven F, van Wingen G (2014). "Allopregnanolone and mood disorders". Prog. Neurobiol. 113: 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.005. PMID 23978486.

- 1 2 Zutshi (2005). Hormones in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Jaypee Brothers, Medical Publishers. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-81-8061-427-9.

It has been observed that micronized progesterone has no suppressive effects on high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C). Jensen et al have proved that oral micronized progesterone has no adverse effect on serum lipids. These preparations have the same antiestrogenic and antimineralocorticoid effect but no androgenic action. It does not affect aldosterone synthesis, blood pressure, carbohydrate metabolism or mood changes. No side effects have been reported as far as lipid profile, coagulation factors and blood pressure are concerned.

- ↑ Lark S (1999). Making the Estrogen Decision. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 22. ISBN 9780879836962.

- ↑ Progesterone - Drugs.com, retrieved 2015-08-23

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 1024–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 880–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ↑ Pincus G, Miyake T, Merrill AP, Longo P (November 1957). "The bioassay of progesterone". Endocrinology. 61 (5): 528–33. doi:10.1210/endo-61-5-528. PMID 13480263.

- ↑ Basu, Krishnakali; Mitra, Ashim K. (1990). "Effects of 3-hydrazone modification on the metabolism and protein binding of progesterone". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 65 (1–2): 109–114. doi:10.1016/0378-5173(90)90015-V. ISSN 0378-5173.

- ↑ Wali B, Sayeed I, Guthrie DB, Natchus MG, Turan N, Liotta DC, Stein DG (October 2016). "Evaluating the neurotherapeutic potential of a water-soluble progesterone analog after traumatic brain injury in rats". Neuropharmacology. 109: 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.05.017. PMID 27267687.

- ↑ Guthrie, D. B., Lockwood, M. A., Natchus, M. G., Liotta, D. C., Stein, D. G., & Sayeed, I. (2017). U.S. Patent No. 9,802,978. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US9802978B2/en

- ↑ MacNevin CJ, Atif F, Sayeed I, Stein DG, Liotta DC (October 2009). "Development and screening of water-soluble analogues of progesterone and allopregnanolone in models of brain injury". J. Med. Chem. 52 (19): 6012–23. doi:10.1021/jm900712n. PMID 19791804.

- ↑ Guthrie DB, Stein DG, Liotta DC, Lockwood MA, Sayeed I, Atif F, Arrendale RF, Reddy GP, Evers TJ, Marengo JR, Howard RB, Culver DG, Natchus MG (May 2012). "Water-soluble progesterone analogues are effective, injectable treatments in animal models of traumatic brain injury". ACS Med Chem Lett. 3 (5): 362–6. doi:10.1021/ml200303r. PMC 4025794. PMID 24900479.

- ↑ https://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800041522

- ↑ Die Gestagene. Springer-Verlag. 27 November 2013. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-3-642-99941-3.

- ↑ Walker A (7 March 2008). The Menstrual Cycle. Routledge. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-1-134-71411-7.

- ↑ Ginsburg B (6 December 2012). Premenstrual Syndrome: Ethical and Legal Implications in a Biomedical Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 274–. ISBN 978-1-4684-5275-4.

- ↑ Gerald, Michael (2013). The Drug Book. New York, New York: Sterling Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 9781402782640.

- 1 2 Minkin MJ, Wright CV (2005). A Woman's Guide to Menopause & Perimenopause. Yale University Press. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-0-300-10435-6.

- ↑ Racowsky C, Schlegel PN, Fauser BC, Carrell D (7 June 2011). Biennial Review of Infertility. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-4419-8456-2.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 020701". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 019781". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 075906". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 022057". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (31 October 1999). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9.

- ↑ Annetine Gelijns (1991). Innovation in Clinical Practice: The Dynamics of Medical Technology Development. National Academies. pp. 195–. NAP:13513.

- ↑ https://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800044558

- ↑ http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800038089

- ↑ Espinoza TR, Wright DW (2011). "The role of progesterone in traumatic brain injury". The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 26 (6): 497–9. doi:10.1097/HTR.0b013e31823088fa. PMID 22088981.

- 1 2 Stein DG (September 2011). "Progesterone in the treatment of acute traumatic brain injury: a clinical perspective and update". Neuroscience. 191: 101–6. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.013. PMID 21497181.

- ↑ Gibson CL, Gray LJ, Bath PM, Murphy SP (February 2008). "Progesterone for the treatment of experimental brain injury; a systematic review". Brain. 131 (Pt 2): 318–28. doi:10.1093/brain/awm183. PMID 17715141.

- ↑ Wright DW, Kellermann AL, Hertzberg VS, Clark PL, Frankel M, Goldstein FC, Salomone JP, Dent LL, Harris OA, Ander DS, Lowery DW, Patel MM, Denson DD, Gordon AB, Wald MM, Gupta S, Hoffman SW, Stein DG (April 2007). "ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 49 (4): 391–402, 402.e1–2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932. PMID 17011666.

- ↑ Xiao G, Wei J, Yan W, Wang W, Lu Z (April 2008). "Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial". Critical Care. 12 (2): R61. doi:10.1186/cc6887. PMC 2447617. PMID 18447940.

- ↑ Cekic M, Sayeed I, Stein DG (July 2009). "Combination treatment with progesterone and vitamin D hormone may be more effective than monotherapy for nervous system injury and disease". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 30 (2): 158–72. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.04.002. PMC 3025702. PMID 19394357.

- ↑ Khaksari M, Soltani Z, Shahrokhi N, Moshtaghi G, Asadikaram G (January 2011). "The role of estrogen and progesterone, administered alone and in combination, in modulating cytokine concentration following traumatic brain injury". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 89 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1139/y10-103. PMID 21186375.

- ↑ "Efficacy and Safety Study of Intravenous Progesterone in Patients With Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (SyNAPSe)". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- ↑ "SyNAPse: The Global phase 3 study of progesterone in severe traumatic brain injury". BHR Pharma, LLC.

- ↑ Sofuoglu M, Mitchell E, Mooney M (October 2009). "Progesterone effects on subjective and physiological responses to intravenous nicotine in male and female smokers". Human Psychopharmacology. 24 (7): 559–64. doi:10.1002/hup.1055. PMC 2785078. PMID 19743227.

Further reading

- Sitruk-Ware R, Bricaire C, De Lignieres B, Yaneva H, Mauvais-Jarvis P (October 1987). "Oral micronized progesterone. Bioavailability pharmacokinetics, pharmacological and therapeutic implications--a review". Contraception. 36 (4): 373–402. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(87)90088-6. PMID 3327648.

- Simon JA (December 1995). "Micronized progesterone: vaginal and oral uses". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 38 (4): 902–14. doi:10.1097/00003081-199538040-00024. PMID 8616985.

- Ruan X, Mueck AO (November 2014). "Systemic progesterone therapy--oral, vaginal, injections and even transdermal?". Maturitas. 79 (3): 248–55. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.009. PMID 25113944.