Anxiety

| Anxiety | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| A person diagnosed with panphobia, from Alexander Morison's 1843 book The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, psychology |

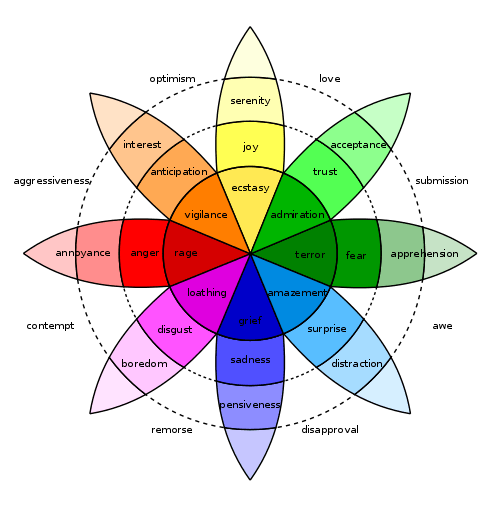

Anxiety is an emotion characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil, often accompanied by nervous behaviour such as pacing back and forth, somatic complaints, and rumination.[1] It is the subjectively unpleasant feelings of dread over anticipated events, such as the feeling of imminent death.[2] Anxiety is not the same as fear, which is a response to a real or perceived immediate threat,[3] whereas anxiety is the expectation of future threat.[3] Anxiety is a feeling of uneasiness and worry, usually generalized and unfocused as an overreaction to a situation that is only subjectively seen as menacing.[4] It is often accompanied by muscular tension,[3] restlessness, fatigue and problems in concentration. Anxiety can be appropriate, but when experienced regularly the individual may suffer from an anxiety disorder.[3]

People facing anxiety may withdraw from situations which have provoked anxiety in the past.[5] There are various types of anxiety. Existential anxiety can occur when a person faces angst, an existential crisis, or nihilistic feelings. People can also face mathematical anxiety, somatic anxiety, stage fright, or test anxiety. Social anxiety and stranger anxiety are caused when people are apprehensive around strangers or other people in general. Furthermore, anxiety has been linked with physical symptoms such as IBS and can heighten other mental health illnesses such as OCD and panic disorder. The first step in the management of a person with anxiety symptoms is to evaluate the possible presence of an underlying medical cause, whose recognition is essential in order to decide its correct treatment.[6][7] Anxiety symptoms may be masking an organic disease, or appear associated or as a result of a medical disorder.[6][7][8][9]

Anxiety can be either a short term "state" or a long term "trait". Whereas trait anxiety represents worrying about future events, anxiety disorders are a group of mental disorders characterized by feelings of anxiety and fear.[10] Anxiety disorders are partly genetic but may also be due to drug use, including alcohol, caffeine, and benzodiazepines (which are often prescribed to treat anxiety), as well as withdrawal from drugs of abuse. They often occur with other mental disorders, particularly bipolar disorder, eating disorders, major depressive disorder, or certain personality disorders. Common treatment options include lifestyle changes, medication, and therapy. Metacognitive therapy seeks to rid anxiety through reducing worry, which is seen as a consequence of metacognitive beliefs.[11]

Fear

Anxiety is distinguished from fear, which is an appropriate cognitive and emotional response to a perceived threat.[12] Anxiety is related to the specific behaviors of fight-or-flight responses, defensive behavior or escape. It occurs in situations only perceived as uncontrollable or unavoidable, but not realistically so.[13] David Barlow defines anxiety as "a future-oriented mood state in which one is not ready or prepared to attempt to cope with upcoming negative events,"[14] and that it is a distinction between future and present dangers which divides anxiety and fear. Another description of anxiety is agony, dread, terror, or even apprehension.[15] In positive psychology, anxiety is described as the mental state that results from a difficult challenge for which the subject has insufficient coping skills.[16]

Fear and anxiety can be differentiated in four domains: (1) duration of emotional experience, (2) temporal focus, (3) specificity of the threat, and (4) motivated direction. Fear is short lived, present focused, geared towards a specific threat, and facilitating escape from threat; anxiety, on the other hand, is long-acting, future focused, broadly focused towards a diffuse threat, and promoting excessive caution while approaching a potential threat and interferes with constructive coping.[17]

Symptoms

Anxiety can be experienced with long, drawn out daily symptoms that reduce quality of life, known as chronic (or generalized) anxiety, or it can be experienced in short spurts with sporadic, stressful panic attacks, known as acute anxiety.[18] Symptoms of anxiety can range in number, intensity, and frequency, depending on the person. While almost everyone has experienced anxiety at some point in their lives, most do not develop long-term problems with anxiety.

Anxiety may cause psychiatric and physiological symptoms.[6][9]

The risk of anxiety leading to depression could possibly even lead to an individual harming themselves, which is why there are many 24-hour suicide prevention hotlines.[19]

The behavioral effects of anxiety may include withdrawal from situations which have provoked anxiety or negative feelings in the past.[5] Other effects may include changes in sleeping patterns, changes in habits, increase or decrease in food intake, and increased motor tension (such as foot tapping).[5]

The emotional effects of anxiety may include "feelings of apprehension or dread, trouble concentrating, feeling tense or jumpy, anticipating the worst, irritability, restlessness, watching (and waiting) for signs (and occurrences) of danger, and, feeling like your mind's gone blank"[20] as well as "nightmares/bad dreams, obsessions about sensations, déjà vu, a trapped-in-your-mind feeling, and feeling like everything is scary."[21]

The cognitive effects of anxiety may include thoughts about suspected dangers, such as fear of dying. "You may ... fear that the chest pains are a deadly heart attack or that the shooting pains in your head are the result of a tumor or an aneurysm. You feel an intense fear when you think of dying, or you may think of it more often than normal, or can't get it out of your mind."[22]

The physiological symptoms of anxiety may include:[6][9]

- Neurological, as headache, paresthesias, vertigo, or presyncope.

- Digestive, as abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, indigestion, dry mouth, or bolus.

- Respiratory, as shortness of breath or sighing breathing.

- Cardiac, as palpitations, tachycardia, or chest pain.

- Muscular, as fatigue, tremors, or tetany.

- Cutaneous, as perspiration, or itchy skin.

- Uro-genital, as frequent urination, urinary urgency, dyspareunia, or impotence.

Types

Existential

The philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, in The Concept of Anxiety (1844), described anxiety or dread associated with the "dizziness of freedom" and suggested the possibility for positive resolution of anxiety through the self-conscious exercise of responsibility and choosing. In Art and Artist (1932), the psychologist Otto Rank wrote that the psychological trauma of birth was the pre-eminent human symbol of existential anxiety and encompasses the creative person's simultaneous fear of – and desire for – separation, individuation, and differentiation.

The theologian Paul Tillich characterized existential anxiety[23] as "the state in which a being is aware of its possible nonbeing" and he listed three categories for the nonbeing and resulting anxiety: ontic (fate and death), moral (guilt and condemnation), and spiritual (emptiness and meaninglessness). According to Tillich, the last of these three types of existential anxiety, i.e. spiritual anxiety, is predominant in modern times while the others were predominant in earlier periods. Tillich argues that this anxiety can be accepted as part of the human condition or it can be resisted but with negative consequences. In its pathological form, spiritual anxiety may tend to "drive the person toward the creation of certitude in systems of meaning which are supported by tradition and authority" even though such "undoubted certitude is not built on the rock of reality".[23]

According to Viktor Frankl, the author of Man's Search for Meaning, when a person is faced with extreme mortal dangers, the most basic of all human wishes is to find a meaning of life to combat the "trauma of nonbeing" as death is near.[24]

Test and performance

According to Yerkes-Dodson law, an optimal level of arousal is necessary to best complete a task such as an exam, performance, or competitive event. However, when the anxiety or level of arousal exceeds that optimum, the result is a decline in performance.[25]

Test anxiety is the uneasiness, apprehension, or nervousness felt by students who have a fear of failing an exam. Students who have test anxiety may experience any of the following: the association of grades with personal worth; fear of embarrassment by a teacher; fear of alienation from parents or friends; time pressures; or feeling a loss of control. Sweating, dizziness, headaches, racing heartbeats, nausea, fidgeting, uncontrollable crying or laughing and drumming on a desk are all common. Because test anxiety hinges on fear of negative evaluation,[26] debate exists as to whether test anxiety is itself a unique anxiety disorder or whether it is a specific type of social phobia.[27] The DSM-IV classifies test anxiety as a type of social phobia.[28]

While the term "test anxiety" refers specifically to students,[29] many workers share the same experience with regard to their career or profession. The fear of failing at a task and being negatively evaluated for failure can have a similarly negative effect on the adult.[30] Management of test anxiety focuses on achieving relaxation and developing mechanisms to manage anxiety.[29]

Stranger, social, and intergroup anxiety

Humans generally require social acceptance and thus sometimes dread the disapproval of others. Apprehension of being judged by others may cause anxiety in social environments.[31]

Anxiety during social interactions, particularly between strangers, is common among young people. It may persist into adulthood and become social anxiety or social phobia. "Stranger anxiety" in small children is not considered a phobia. In adults, an excessive fear of other people is not a developmentally common stage; it is called social anxiety. According to Cutting,[32] social phobics do not fear the crowd but the fact that they may be judged negatively.

Social anxiety varies in degree and severity. For some people, it is characterized by experiencing discomfort or awkwardness during physical social contact (e.g. embracing, shaking hands, etc.), while in other cases it can lead to a fear of interacting with unfamiliar people altogether. Those suffering from this condition may restrict their lifestyles to accommodate the anxiety, minimizing social interaction whenever possible. Social anxiety also forms a core aspect of certain personality disorders, including avoidant personality disorder.[33]

To the extent that a person is fearful of social encounters with unfamiliar others, some people may experience anxiety particularly during interactions with outgroup members, or people who share different group memberships (i.e., by race, ethnicity, class, gender, etc.). Depending on the nature of the antecedent relations, cognitions, and situational factors, intergroup contact may be stressful and lead to feelings of anxiety. This apprehension or fear of contact with outgroup members is often called interracial or intergroup anxiety.[34]

As is the case the more generalized forms of social anxiety, intergroup anxiety has behavioral, cognitive, and affective effects. For instance, increases in schematic processing and simplified information processing can occur when anxiety is high. Indeed, such is consistent with related work on attentional bias in implicit memory.[35][36][37] Additionally recent research has found that implicit racial evaluations (i.e. automatic prejudiced attitudes) can be amplified during intergroup interaction.[38] Negative experiences have been illustrated in producing not only negative expectations, but also avoidant, or antagonistic, behavior such as hostility.[39] Furthermore, when compared to anxiety levels and cognitive effort (e.g., impression management and self-presentation) in intragroup contexts, levels and depletion of resources may be exacerbated in the intergroup situation.

Trait

Anxiety can be either a short-term 'state' or a long-term personality "trait". Trait anxiety reflects a stable tendency across the lifespan of responding with acute, state anxiety in the anticipation of threatening situations (whether they are actually deemed threatening or not).[40] A meta-analysis showed that a high level of neuroticism is a risk factor for development of anxiety symptoms and disorders.[41] Such anxiety may be conscious or unconscious.[42]

Personality can also be a trait leading towards anxiety and depression. Through experience many find it difficult to collect themselves due to their own personal nature.[43]

Choice or decision

Anxiety induced by the need to choose between similar options is increasingly being recognized as a problem for individuals and for organizations.[44] In 2004, Capgemini wrote: "Today we're all faced with greater choice, more competition and less time to consider our options or seek out the right advice."[45]

In a decision context, unpredictability or uncertainty may trigger emotional responses in anxious individuals that systematically alter decision-making.[46] There are primarily two forms of this anxiety type. The first form refers to a choice in which there are multiple potential outcomes with known or calculable probabilities. The second form refers to the uncertainty and ambiguity related to a decision context in which there are multiple possible outcomes with unknown probabilities.[46]

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders are a group of mental disorders characterized by exaggerated feelings of anxiety and fear responses.[10] Anxiety is a worry about future events and fear is a reaction to current events. These feelings may cause physical symptoms, such as a fast heart rate and shakiness. There are a number of anxiety disorders: including generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and selective mutism. The disorder differs by what results in the symptoms. People often have more than one anxiety disorder.[10]

The cause of anxiety disorders is a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[47] Anxiety can stem itself from certain factors: genetics, medicinal side-effects, shortness of oxygen. [48]Risk factors include a history of child abuse, family history of mental disorders, and poverty. Anxiety disorders often occur with other mental disorders, particularly major depressive disorder, personality disorder, and substance use disorder.[49] To be diagnosed symptoms typically need to be present at least six months, be more than would be expected for the situation, and decrease functioning.[10][49] Other problems that may result in similar symptoms including hyperthyroidism, heart disease, caffeine, alcohol, or cannabis use, and withdrawal from certain drugs, among others.[49][7]

Without treatment, anxiety disorders tend to remain.[10][47] Treatment may include lifestyle changes, counselling, and medications. Counselling is typically with a type of cognitive behavioural therapy.[49] Medications, such as antidepressants or beta blockers, may improve symptoms.[47]

About 12% of people are affected by an anxiety disorder in a given year and between 5-30% are affected at some point in their life.[49][50] They occur about twice as often in women than they do in men, and generally begin before the age of 25.[10][49] The most common are specific phobia which affects nearly 12% and social anxiety disorder which affects 10% at some point in their life. They affect those between the ages of 15 and 35 the most and become less common after the age of 55. Rates appear to be higher in the United States and Europe.[49]

Risk factors

.jpg)

Neuroanatomy

Neural circuitry involving the amygdala (which regulates emotions like anxiety and fear, stimulating the HPA Axis and sympathetic nervous system) and hippocampus (which is implicated in emotional memory along with the amygdala) is thought to underlie anxiety.[52] People who have anxiety tend to show high activity in response to emotional stimuli in the amygdala.[53] Some writers believe that excessive anxiety can lead to an overpotentiation of the limbic system (which includes the amygdala and nucleus accumbens), giving increased future anxiety, but this does not appear to have been proven.[54][55]

Research upon adolescents who as infants had been highly apprehensive, vigilant, and fearful finds that their nucleus accumbens is more sensitive than that in other people when deciding to make an action that determined whether they received a reward.[56] This suggests a link between circuits responsible for fear and also reward in anxious people. As researchers note, "a sense of 'responsibility', or self-agency, in a context of uncertainty (probabilistic outcomes) drives the neural system underlying appetitive motivation (i.e., nucleus accumbens) more strongly in temperamentally inhibited than noninhibited adolescents".[56]

Genetics

Genetics and family history (e.g., parental anxiety) may predispose an individual for an increased risk of an anxiety disorder, but generally external stimuli will trigger its onset or exacerbation.[57] Genetic differences account for about 43% of variance in panic disorder and 28% in generalized anxiety disorder.[58] Although single genes are neither necessary nor sufficient for anxiety by themselves, several gene polymorphisms have been found to correlate with anxiety: PLXNA2, SERT, CRH, COMT and BDNF.[59][60][61] Several of these genes influence neurotransmitters (such as serotonin and norepinephrine) and hormones (such as cortisol) which are implicated in anxiety. The epigenetic signature of at least one of these genes BDNF has also been associated with anxiety and specific patterns of neural activity.[62]

Medical conditions

Many medical conditions can cause anxiety. This includes conditions that affect the ability to breathe, like COPD and asthma, and the difficulty in breathing that often occurs near death.[63][64][65] Conditions that cause abdominal pain or chest pain can cause anxiety and may in some cases be a somatization of anxiety;[66][67] the same is true for some sexual dysfunctions.[68][69] Conditions that affect the face or the skin can cause social anxiety especially among adolescents,[70] and developmental disabilities often lead to social anxiety for children as well.[71] Life-threatening conditions like cancer also cause anxiety.[72]

Furthermore, certain organic diseases may present with anxiety or symptoms that mimic anxiety.[6][7] These disorders include certain endocrine diseases (hypo- and hyperthyroidism, hyperprolactinemia),[7][73] metabolic disorders (diabetes),[7][74][75] deficiency states (low levels of vitamin D, B2, B12, folic acid),[7] gastrointestinal diseases (celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, inflammatory bowel disease),[76][77][78] heart diseases, blood diseases (anemia),[7] cerebral vascular accidents (transient ischemic attack, stroke),[7] and brain degenerative diseases (Parkinson's disease, dementia, multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease), among others.[7][79][80][81]

Substance-induced

Several drugs can cause or worsen anxiety, whether in intoxication, withdrawal or from chronic use. These include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, sedatives (including prescription benzodiazepines), opioids (including prescription pain killers and illicit drugs like heroin), stimulants (such as caffeine, cocaine and amphetamines), hallucinogens, and inhalants.[57] While many often report self-medicating anxiety with these substances, improvements in anxiety from drugs are usually short-lived (with worsening of anxiety in the long term, sometimes with acute anxiety as soon as the drug effects wear off) and tend to be exaggerated. Acute exposure to toxic levels of benzene may cause euphoria, anxiety, and irritability lasting up to 2 weeks after the exposure.[82]

Psychological

Poor coping skills (e.g., rigidity/inflexible problem solving, denial, avoidance, impulsivity, extreme self-expectation, negative thoughts, affective instability, and inability to focus on problems) are associated with anxiety. Anxiety is also linked and perpetuated by the person's own pessimistic outcome expectancy and how they cope with feedback negativity.[83] Temperament (e.g., neuroticism)[41] and attitudes (e.g. pessimism) have been found to be risk factors for anxiety.[57][84]

Cognitive distortions such as overgeneralizing, catastrophizing, mind reading, emotional reasoning, binocular trick, and mental filter can result in anxiety. For example, an overgeneralized belief that something bad "always" happens may lead someone to have excessive fears of even minimally risky situations and to avoid benign social situations due to anticipatory anxiety of embarrassment. In addition, those who have high anxiety can also create future stressful life events. [85] Together, these findings suggest that anxious thoughts can lead to anticipatory anxiety as well stressful events, which in turn cause more anxiety. Such unhealthy thoughts can be targets for successful treatment with cognitive therapy.

Psychodynamic theory posits that anxiety is often the result of opposing unconscious wishes or fears that manifest via maladaptive defense mechanisms (such as suppression, repression, anticipation, regression, somatization, passive aggression, dissociation) that develop to adapt to problems with early objects (e.g., caregivers) and empathic failures in childhood. For example, persistent parental discouragement of anger may result in repression/suppression of angry feelings which manifests as gastrointestinal distress (somatization) when provoked by another while the anger remains unconscious and outside the individual's awareness. Such conflicts can be targets for successful treatment with psychodynamic therapy. While psychodynamic therapy tends to explore the underlying roots of anxiety, cognitive behavioral therapy has also been shown to be a successful treatment for anxiety by altering irrational thoughts and unwanted behaviors.

Evolutionary psychology

An evolutionary psychology explanation is that increased anxiety serves the purpose of increased vigilance regarding potential threats in the environment as well as increased tendency to take proactive actions regarding such possible threats. This may cause false positive reactions but an individual suffering from anxiety may also avoid real threats. This may explain why anxious people are less likely to die due to accidents.[86]

When people are confronted with unpleasant and potentially harmful stimuli such as foul odors or tastes, PET-scans show increased bloodflow in the amygdala.[87][88] In these studies, the participants also reported moderate anxiety. This might indicate that anxiety is a protective mechanism designed to prevent the organism from engaging in potentially harmful behaviors.

Social

Social risk factors for anxiety include a history of trauma (e.g., physical, sexual or emotional abuse or assault), early life experiences and parenting factors (e.g., rejection, lack of warmth, high hostility, harsh discipline, high parental negative affect, anxious childrearing, modelling of dysfunctional and drug-abusing behaviour, discouragement of emotions, poor socialization, poor attachment, and child abuse and neglect), cultural factors (e.g., stoic families/cultures, persecuted minorities including the disabled), and socioeconomics (e.g., uneducated, unemployed, impoverished (although developed countries have higher rates of anxiety disorders than developing countries).[57][89]

Gender socialization

Contextual factors that are thought to contribute to anxiety include gender socialization and learning experiences. In particular, learning mastery (the degree to which people perceive their lives to be under their own control) and instrumentality, which includes such traits as self-confidence, independence, and competitiveness fully mediate the relation between gender and anxiety. That is, though gender differences in anxiety exist, with higher levels of anxiety in women compared to men, gender socialization and learning mastery explain these gender differences.[90] Research has demonstrated the ways in which facial prominence in photographic images differs between men and women. More specifically, in official online photographs of politicians around the world, women's faces are less prominent than men's. The difference in these images actually tended to be greater in cultures with greater institutional gender equality.[91]

Pathophysiology

Anxiety disorder appears to be a genetically inherited neurochemical dysfunction that may involve autonomic imbalance; decreased GABA-ergic tone; allelic polymorphism of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene; increased adenosine receptor function; increased cortisol. In the central nervous system (CNS), the major mediators of the symptoms of anxiety disorders appear to be norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Other neurotransmitters and peptides, such as corticotropin-releasing factor, may be involved. Peripherally, the autonomic nervous system, especially the sympathetic nervous system, mediates many of the symptoms. Increased flow in the right parahippocampal region and reduced serotonin type 1A receptor binding in the anterior and posterior cingulate and raphe of patients are the diagnostic factors for prevalence of anxiety disorder. The amygdala is central to the processing of fear and anxiety, and its function may be disrupted in anxiety disorders. Anxiety processing in the basolateral amygdala has been implicated with dendritic arborization of the amygdaloid neurons. SK2 potassium channels mediate inhibitory influence on action potentials and reduce arborization.

See also

References

- ↑ Seligman, M.E.P.; Walker, E.F.; Rosenhan, D.L. Abnormal psychology (4th ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ Davison, Gerald C. (2008). Abnormal Psychology. Toronto: Veronica Visentin. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-470-84072-6.

- 1 2 3 4 American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ Bouras, N.; Holt, G. (2007). Psychiatric and Behavioral Disorders in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 3 Barker, P. (2003). Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: The Craft of Caring. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-81026-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 World Health Organization (2009). Pharmacological Treatment of Mental Disorders in Primary Health Care (PDF). Geneva. ISBN 978-92-4-154769-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Testa A, Giannuzzi R, Daini S, Bernardini L, Petrongolo L, Gentiloni Silveri N (2013). "Psychiatric emergencies (part III): psychiatric symptoms resulting from organic diseases" (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (Review). 17 Suppl 1: 86–99. PMID 23436670. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Testa A, Giannuzzi R, Sollazzo F, Petrongolo L, Bernardini L, Daini S (2013). "Psychiatric emergencies (part II): psychiatric disorders coexisting with organic diseases" (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 17 (Suppl 1): 65–85. PMID 23436668. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Testa A, Giannuzzi R, Sollazzo F, Petrongolo L, Bernardini L, Daini S (2013). "Psychiatric emergencies (part I): psychiatric disorders causing organic symptoms" (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 17 (Suppl 1): 55–64. PMID 23436668. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental DisordersAmerican Psychiatric Associati (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. pp. 189–195. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ↑ Wells, Adrian (2011). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression (Pbk. ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN 9781609184964. OCLC 699763619.

- ↑ Andreas Dorschel, Furcht und Angst. In: Dietmar Goltschnigg (ed.), Angst. Lähmender Stillstand und Motor des Fortschritts. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2012, pp. 49-54

- ↑ Öhman, Arne (2000). "Fear and anxiety: Evolutionary, cognitive, and clinical perspectives". In Lewis, Michael; Haviland-Jones, Jeannette M. Handbook of emotions. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 573–93. ISBN 978-1-57230-529-8.

- ↑ Barlow, David H. (2000). "Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory". American Psychologist. 55 (11): 1247–63. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.11.1247. PMID 11280938.

- ↑ Iacovou, Susan (July 2011). "What is the Difference Between Existential Anxiety and so Called Neurotic Anxiety?: 'The sine qua non of true vitality': An Examination of the Difference Between Existential Anxiety and Neurotic Anxiety". Existential Analysis. 22 (2): 356–67. ISSN 1752-5616. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014.

- ↑ Csíkszentmihályi, Mihály (1997). Finding Flow.

- ↑ Sylvers, Patrick; Lilienfeld, Scott O.; Laprairie, Jamie L. (2011). "Differences between trait fear and trait anxiety: Implications for psychopathology". Clinical Psychology Review. 31 (1): 122–37. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.004. PMID 20817337.

- ↑ Rynn MA, Brawman-Mintzer O (2004). "Generalized anxiety disorder: acute and chronic treatment". CNS Spectr. 9 (10): 716–23. PMID 15448583.

- ↑ "Depression Hotline | Call Our Free, 24 Hour Depression Helpline". PsychGuides.com. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ Smith, Melinda (2008, June). Anxiety attacks and disorders: Guide to the signs, symptoms, and treatment options. Retrieved March 3, 2009, from Helpguide Web site: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ (1987–2008). Anxiety Symptoms, Anxiety Attack Symptoms (Panic Attack Symptoms), Symptoms of Anxiety. Retrieved March 3, 2009, from Anxiety Centre Website: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ↑ (1987–2008). Anxiety symptoms - Fear of dying. Retrieved March 3, 2009, from Anxiety Centre Website: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- 1 2 Tillich, Paul (1952). The Courage To Be. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-300-08471-4.

- ↑ Abulof, Uriel (2015). The Mortality and Morality of Nations. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9781107097070.

- ↑ Teigen, Karl Halvor (November 1994). "Yerkes-Dodson: A Law for all Seasons". Theory Psychology. 4 (4): 525–47. doi:10.1177/0959354394044004.

- ↑ Liebert, Robert M.; Morris, Larry W. (1967). "Cognitive and emotional components of test anxiety: A distinction and some initial data". Psychological Reports. 20 (3): 975–978. doi:10.2466/pr0.1967.20.3.975. PMID 6042522.

- ↑ Beidel, D.C.; Turner, S.M. (1988). "Comorbidity of test anxiety and other anxiety disorders in children". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 16 (3): 275–287. doi:10.1007/BF00913800. PMID 3403811.

- ↑ Rapee, Ronald M.; Heimberg, Richard G. (August 1997). "A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 35 (8): 741–56. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00022-3. PMID 9256517.

- 1 2 Mathur, S.; Khan, W. (October 2011). "Impact of Hypnotherapy on examination anxiety and scholastic performance among school children" (PDF). Delhi Psychiatry Journal. 14 (2): 337–342. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2016.

- ↑ Hall-Flavin, Daniel K. "Is it possible to overcome test anxiety?". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ↑ Hofmann, Stefan G.; Dibartolo, Patricia M. (2010). "Introduction: Toward an Understanding of Social Anxiety Disorder". Social Anxiety. pp. xix–xxvi. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-375096-9.00028-6. ISBN 978-0-12-375096-9.

- ↑ Thomas, Ben; Hardy, Sally; Cutting, Penny, eds. (1997). Mental Health Nursing: Principles and Practice. London: Mosby. ISBN 978-0-7234-2590-8.

- ↑ Settipani, Cara A.; Kendall, Philip C. (2012). "Social Functioning in Youth with Anxiety Disorders: Association with Anxiety Severity and Outcomes from Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy". Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 44 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1007/s10578-012-0307-0. PMID 22581270.

- ↑ Stephan, Walter G.; Stephan, Cookie W. (1985). "Intergroup anxiety". Journal of Social Issues. 41 (3): 157–175. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.

- ↑ Richeson, Jennifer A.; Trawalter, Sophie (2008). "The threat of appearing prejudiced and race-based attentional biases". Psychological Science. 19 (2): 98–102. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02052.x. PMID 18271854.

- ↑ Mathews, Andrew; Mogg, Karin; May, Jon; Eysenck, Michael (1989). "Implicit and explicit memory bias in anxiety". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 98 (3): 236–240. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.98.3.236.

- ↑ Richards, Anne; French, Christopher C. (1991). "Effects of encoding and anxiety on implicit and explicit memory performance". Personality and Individual Differences. 12 (2): 131–139. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(91)90096-t.

- ↑ Amodio, David M.; Hamilton, Holly K. (2012). "Intergroup anxiety effects on implicit racial evaluation and stereotyping". Emotion. 12 (6): 1273–1280. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.659.5717. doi:10.1037/a0029016.

- ↑ Plant, Ashby E.; Devine, Patricia G. (2003). "The antecedents and Implications of Interracial Anxiety". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 29: 790–801. doi:10.1177/0146167203029006011.

- ↑ Schwarzer, R. (December 1997). "Anxiety". Archived from the original on September 20, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- 1 2 Jeronimus B.F.; Kotov, R.; Riese, H.; Ormel, J. (2016). "Neuroticism's prospective association with mental disorders halves after adjustment for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, but the adjusted association hardly decays with time: a meta-analysis on 59 longitudinal/prospective studies with 443 313 participants". Psychological Medicine. 46: 2883–2906. doi:10.1017/S0033291716001653. PMID 27523506.

- ↑ Giddey, M.; Wright, H. Mental Health Nursing: From first principles to professional practice. Stanley Thornes.

- ↑ "Gulf Bend MHMR Center". Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ Downey, Jonathan (April 27, 2008). "Premium choice anxiety". The Times. London. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ↑ Is choice anxiety costing british 'blue chip' business? Archived December 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., Capgemini, Aug 16, 2004

- 1 2 Hartley, Catherine A.; Phelps, Elizabeth A. (2012). "Anxiety and Decision-Making". Biological Psychiatry. 72 (2): 113–8. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.027. PMC 3864559. PMID 22325982.

- 1 2 3 "Anxiety Disorders". NIMH. March 2016. Archived from the original on July 27, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ↑ The MNT Editorial Team. "What causes anxiety?".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Craske, MG; Stein, MB (24 June 2016). "Anxiety". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30381-6. PMID 27349358.

- ↑ Kessler; et al. (2007). "Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative". World Psychiatry. 6 (3): 168–76. PMC 2174588. PMID 18188442.

- ↑ Scarre, Chris (1995). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors. Thames & Hudson. pp. 168–9. ISBN 978-5-00-050775-9.

- ↑ Rosen, Jeffrey B.; Schulkin, Jay (1998). "From normal fear to pathological anxiety". Psychological Review. 105 (2): 325–50. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.105.2.325. PMID 9577241.

- ↑ Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). (Ab)normal Psychology (6th edition). McGraw Hill.

- ↑ Fricchione, G. (2011). Compassion and Healing in Medicine and Society: On the Nature and Use of Attachment Solutions to Separation Challenges. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 172. ISBN 9781421402208. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016.

- ↑ Harris, J. (1998). How the Brain Talks to Itself: A Clinical Primer of Psychotherapeutic Neuroscience. Haworth. p. 284. ISBN 9780789004086. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016.

- 1 2 Bar-Haim, Yair; Fox, Nathan A.; Benson, Brenda; Guyer, Amanda E.; Williams, Amber; Nelson, Eric E.; Perez-Edgar, Koraly; Pine, Daniel S.; Ernst, Monique (2009). "Neural Correlates of Reward Processing in Adolescents with a History of Inhibited Temperament". Psychological Science. 20 (8): 1009–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02401.x. PMC 2785902. PMID 19594857.

- 1 2 3 4 American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- ↑ Bienvenu, O. J.; Davydow, D. S.; Kendler, K. S. (2011-01-01). "Psychiatric 'diseases' versus behavioral disorders and degree of genetic influence". Psychological Medicine. 41 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1017/S003329171000084X. ISSN 1469-8978. PMID 20459884.

- ↑ Wray, Naomi R.; James, Michael R.; Mah, Steven P.; Nelson, Matthew; Andrews, Gavin; Sullivan, Patrick F.; Montgomery, Grant W.; Birley, Andrew J.; Braun, Andreas; Martin, NG (2007). "Anxiety and Comorbid Measures Associated with PLXNA2" (PDF). Archives of General Psychiatry. 64 (3): 318–26. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.318. PMID 17339520.

- ↑ Chen ZY, Jing D, Bath KG, Ieraci A, Khan T, Siao CJ, et al. (2006). "Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior". Science. 314 (5796): 140–3. Bibcode:2006Sci...314..140C. doi:10.1126/science.1129663. PMC 1880880. PMID 17023662.

- ↑ Tocchetto A, Salum GA, Blaya C, Teche S, Isolan L, Bortoluzzi A, et al. (Sep 2011). "Evidence of association between Val66Met polymorphism at BDNF gene and anxiety disorders in a community sample of children and adolescents". Neurosci. Lett. 502 (3): 197–200. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.044.

- ↑ Moser DA, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Stenz L, Adouan W, Manini A, Suardi F, et al. (2015). "BDNF Methylation and Maternal Brain Activity in a Violence-Related Sample". PLoS ONE. 10 (12): e0143427. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043427M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143427. PMC 4674054. PMID 26649946.

- ↑ Baldwin, Jennifer; Cox, Jaclyn (September 2016). "Treating Dyspnea". Medical Clinics of North America. 100 (5): 1123–1130. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2016.04.018. PMID 27542431.

- ↑ Vanfleteren, Lowie E G W; Spruit, Martijn A; Wouters, Emiel F M; Franssen, Frits M E (November 2016). "Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease beyond the lungs". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 4 (11): 911–924. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00097-7. PMID 27264777.

- ↑ Tselebis A, Pachi A, Ilias I, Kosmas E, Bratis D, Moussas G, et al. (2016). "Strategies to improve anxiety and depression in patients with COPD: a mental health perspective". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat (Review). 12: 297–328. doi:10.2147/NDT.S79354. PMC 4755471. PMID 26929625.

- ↑ Muscatello, Maria Rosaria A; Bruno, Antonio; Mento, Carmela; Pandolfo, Gianluca; Zoccali, Rocco A (2016). "Personality traits and emotional patterns in irritable bowel syndrome". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (28): 6402–15. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6402. PMC 4968122. PMID 27605876.

- ↑ Remes-Troche, Jose M. (5 October 2016). "How to Diagnose and Treat Functional Chest Pain". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 14 (4): 429–443. doi:10.1007/s11938-016-0106-y. PMID 27709331.

- ↑ Brotto, Lori; et al. (April 2016). "Psychological and Interpersonal Dimensions of Sexual Function and Dysfunction". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 13 (4): 538–571. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.019. PMID 27045257. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017.

- ↑ McMahon, Chris G.; Jannini, Emmanuele A.; Serefoglu, Ege C.; Hellstrom, Wayne J. G. (August 2016). "The pathophysiology of acquired premature ejaculation". Translational Andrology and Urology. 5 (4): 434–449. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.07.06. PMC 5001985. PMID 27652216.

- ↑ Nguyen, Catherine; Beroukhim, Kourosh; Danesh, Melissa; Babikian, Aline; Koo, John; Leon, Argentina (October 2016). "The psychosocial impact of acne, vitiligo, and psoriasis: a review". Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 9: 383–392. doi:10.2147/CCID.S76088. PMC 5076546. PMID 27799808.

- ↑ Caçola, Priscila (24 October 2016). "Physical and Mental Health of Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder". Frontiers in Public Health. 4. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00224. PMC 5075567. PMID 27822464.

- ↑ Mosher, Catherine E.; Winger, Joseph G.; Given, Barbara A.; Helft, Paul R.; O'Neil, Bert H. (November 2016). "Mental health outcomes during colorectal cancer survivorship: a review of the literature". Psycho-Oncology. 25 (11): 1261–1270. doi:10.1002/pon.3954. PMC 4894828. PMID 26315692.

- ↑ Samuels MH (2008). "Cognitive function in untreated hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism". Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes (Review). 15 (5): 429–33. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32830eb84c. PMID 18769215.

- ↑ Buchberger B, Huppertz H, Krabbe L, Lux B, Mattivi JT, Siafarikas A (2016). "Symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Psychoneuroendocrinology (Systematic Review). 70: 70–84. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.019. PMID 27179232.

- ↑ Grigsby AB, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2002). "Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: a systematic review". J Psychosom Res (Systematic Review). 53 (6): 1053–60. PMID 12479986.

- ↑ Zingone F, Swift GL, Card TR, Sanders DS, Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC (Apr 2015). "Psychological morbidity of celiac disease: A review of the literature". United European Gastroenterol J (Review). 3 (2): 136–45. doi:10.1177/2050640614560786. PMC 4406898. PMID 25922673.

- ↑ Molina-Infante J, Santolaria S, Sanders DS, Fernández-Bañares F (May 2015). "Systematic review: noncoeliac gluten sensitivity". Aliment Pharmacol Ther (Systematic Review). 41 (9): 807–20. doi:10.1111/apt.13155. PMID 25753138.

- ↑ Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, Hanes D, Wahbeh H (2016). "Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review". J Psychosom Res (Systematic Review). 87: 70–80. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001. PMID 27411754.

- ↑ Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, et al. (2016). "The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis". J Affect Disord (Systematic Review). 190: 264–71. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069. PMID 26540080.

- ↑ Wen MC, Chan LL, Tan LC, Tan EK (2016). "Depression, anxiety, and apathy in Parkinson's disease: insights from neuroimaging studies". Eur J Neurol (Review). 23 (6): 1001–19. doi:10.1111/ene.13002. PMC 5084819. PMID 27141858.

- ↑ Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, Stuve O, Trojano M, Sorensen PS, et al. (2015). "The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Mult Scler (Systematic Review). 21 (3): 305–17. doi:10.1177/1352458514564487. PMC 4429164. PMID 25583845.

- ↑ "CDC - The Emergency Response Safety and Health Database: Systemic Agent: BENZENE - NIOSH". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ Gu, Ruolei; Huang, Yu-Xia; Luo, Yue-Jia (2010). "Anxiety and feedback negativity". Psychophysiology. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.00997.x.

- ↑ Bienvenu, O. Joseph; Ginsburg, Golda S. (2007). "Prevention of anxiety disorders". International Review of Psychiatry. 19 (6): 647–54. doi:10.1080/09540260701797837. PMID 18092242.

- ↑ Phillips, Anna C.; Carroll, Douglas; Der, Geoff (2015-07-04). "Negative life events and symptoms of depression and anxiety: stress causation and/or stress generation". Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 28 (4): 357–371. doi:10.1080/10615806.2015.1005078. ISSN 1061-5806. PMC 4772121. PMID 25572915.

- ↑ Andrews, Paul W.; Thomson Jr, J. Anderson (2009). "The bright side of being blue: Depression as an adaptation for analyzing complex problems". Psychological Review. 116 (3): 620–54. doi:10.1037/a0016242. PMC 2734449. PMID 19618990.

- ↑ Zald, David H.; Pardo, Jose V. (1997). "Emotion, olfaction, and the human amygdala: Amygdala activation during aversive olfactory stimulation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (8): 4119–24. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.4119Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.8.4119. JSTOR 41966. PMC 20578. PMID 9108115.

- ↑ Zald, David H.; Hagen, Mathew C.; Pardo, José V. (2002). "Neural Correlates of Tasting Concentrated Quinine and Sugar Solutions". Journal of Neurophysiology. 87 (2): 1068–75. PMID 11826070.

- ↑ O'Connell, Mary Ellen; Boat, Thomas; Warner, Kenneth E., eds. (2009). "Table E-4 Risk Factors for Anxiety". Prevention of Mental Disorders, Substance Abuse, and Problem Behaviors: A Developmental Perspective. National Academies Press. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-309-12674-8. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014.

- ↑ Anticipatory Anxiety Patterns for Male and Female Public Speakers Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Ralph Behnke and Chris Sawyer, 1999

- ↑ Zalta, Alyson K.; Chambless, Dianne L. (2012). "Understanding Gender Differences in Anxiety: The Mediating Effects of Instrumentality and Mastery". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 36 (4): 488–9. doi:10.1177/0361684312450004.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Library resources about Anxiety |