Hormone replacement therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT), also known as menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) or postmenopausal hormone therapy (PHT, PMHT), is a form of hormone therapy which is used to treat symptoms associated with menopause in women.[1][2] These symptoms can include hot flashes, vaginal atrophy and dryness, and bone loss, among others, and are caused by diminished levels of sex hormones in the menopausal period.[1][2] The main hormonal medications used in HRT for menopausal symptoms are estrogens and progestogens.[3] A progestogen is usually used in combination with an estrogen in women with intact uteruses because unopposed estrogen therapy is associated with endometrial hyperplasia and cancer and progestogens prevent these risks.[3][4][5] Androgens, like testosterone, are sometimes used in HRT as well.[6] HRT medications are available in various forms and for use by a variety of different routes of administration.[3]

The 2002 Women's Health Initiative (WHI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found disparate results for all cause mortality with HRT, finding it to be lower when HRT was begun earlier, between age 50 to 59, but higher when begun after age 60. In older patients, there was an increased incidence of breast cancer, heart attacks and stroke, although a reduced incidence of colorectal cancer and bone fracture.[7] Some of the WHI findings were again found in a larger national study done in the United Kingdom, known as the Million Women Study (MWS). As a result of these findings, the number of women taking HRT dropped precipitously.[8] The WHI recommended that women with non-surgical menopause take the lowest feasible dose of HRT for the shortest possible time to minimize associated risks.[7]

The current indications for use from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) include short-term treatment of menopausal symptoms, such as vasomotor hot flashes or vaginal atrophy, and prevention of osteoporosis.[9] In 2012 and 2017, the United States Preventive Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that the harmful effects of combined estrogen and progestin therapy are likely to exceed the chronic disease prevention benefits in most women.[10][11][12] A consensus expert opinion published by The Endocrine Society stated that when taken during perimenopause, or the initial years of menopause, HRT carries significantly fewer risks than previously published, and reduces all cause mortality in most patient scenarios.[13] The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) also released a position statement in 2009 that approved of HRT in appropriate clinical scenarios.

Medical uses

HRT is used to treat or prevent menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal, perimenopausal, and surgically menopausal women, including the following:[1][2]

- Hot flashes (vasomotor symptoms)

- Vulvovaginal atrophy (atrophic vaginitis; including vaginal dryness)

- Dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse, due to vaginal atrophy and lack of vaginal lubrication)

- Bone loss (decreased bone mineral density, which can eventually lead to osteopenia, osteoporosis, and associated bone fractures)

- Decreased sexual desire

- Defeminization (e.g., diminished feminine fat distribution, worsened skin appearance and accelerated skin aging)[14][15]

- Additional symptoms such as sleep disturbances, joint pain, and possibly others

It is also used for health benefits, such as reduced risk of dementia, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, and others. However, this may be counterbalanced by various health risks, like an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer.

HRT is often given as a short-term relief (often one or two years, usually less than five) from menopausal symptoms (such as hot flashes, irregular menstruation). Such treatments aren't usually recommended to women who are perimenopausal or for at least 12 months after the last menstrual period.[16] Younger women with premature ovarian failure or surgical menopause may use HRT for many years, until the age that natural menopause would be expected to occur.

Available forms

There are several different types of hormonal medications which are used in HRT for menopausal symptoms:[3]

- Estrogens – bioidentical estrogens like estradiol and estriol, animal-derived estrogens like conjugated estrogens (CEEs), and synthetic estrogens like ethinylestradiol

- Progestogens – bioidentical progesterone, and progestins (synthetic progestins) like medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), norethisterone, and dydrogesterone

- Androgens – bioidentical testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and synthetic anabolic steroids like methyltestosterone and nandrolone decanoate[17][18]

Tibolone is a unique medication which has the properties of an estrogen, progestogen, and androgen all in one molecule.[3]

The medications used in menopausal HRT are available in numerous different formulations for use by a variety of different routes of administration:[3]

- Oral administration (tablets, capsules)

- Transdermal administration (patches, gels, creams)

- Vaginal administration (tablets, creams, suppositories, rings)

- Intramuscular or subcutaneous injection (solutions in vials or ampoules)

- Subcutaneous implant (surgically-inserted pellets placed into fat tissue)

- Other less common routes like sublingual, buccal, intranasal, and rectal administration, as well as intrauterine devices

HRT for menopause generally provides low dosages of one or more estrogens, and usually also provides a progestogen. In women with intact uteruses, estrogens are almost always given in combination with progestogens, as long-term unopposed estrogen therapy is associated with a markedly increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer.[3] Conversely, in women who have undergone a hysterectomy or who otherwise do not have a uterus, a progestogen is not necessarily required, and an estrogen can be used alone if preferred. There are many combined formulations which include both an estrogen and a progestogen. Examples include the combination of CEEs and MPA (brand name Prempro), as well as the combination of estradiol with one of various progestins such as norethisterone (in Activelle, Novofem, Cliovelle), MPA (in Indivina), levonorgestrel, dienogest, and drospirenone, among others.

Dosage is often varied cyclically to more closely mimic the ovarian hormone cycle, with estrogens taken daily and progestogens taken for about two weeks every month or two; a method called "cyclic HRT" or "sequentially combined HRT" (abbreviated scHRT). An alternate method, a constant dosage with both types of hormones taken daily, is called "continuous combined HRT" or ccHRT, and is a more recent innovation. Vaginal estrogen can have more effect on atrophic vaginitis with fewer systemic effects than estrogens delivered by other routes.[19] Sometimes an androgen, generally testosterone, is added to treat diminished libido. It may also treat reduced energy and help reduce osteoporosis after menopause.

Bioidentical hormone therapy

Bioidentical hormone therapy (BHT) is the use of hormones that are chemically identical to those produced in a woman's body. Proponents of BHT claim that it can offer advantages over non-bioidentical or conventional hormone therapy (CHT).[20][21] There are two different meanings to BHT as a term and therapy, which has resulted in some confusion. While both deal with the use of bioidentical hormones, one meaning concerns the specific use of certain compounded hormone preparations, usually in conjunction with blood or saliva testing to determine, and adjust, a woman's hormone levels; whereas the other meaning simply refers to the use of bioidentical hormones in general, but most typically as approved pharmaceutical preparations.[20][22][23] The practices associated with the first meaning are not widely accepted in clinical medicine. Compounded BHT, including custom-compounded products like BiEst (20% estradiol and 80% estriol) and TriEst (10% estradiol, 10% estrone, and 80% estriol), has not demonstrated any benefits over CHT, and presents risks of uncertain dosing, potency, and possible contamination.[20] In addition, blood or saliva testing is of limited utility due to natural fluctuations in hormone levels, and lack of consensus for ideal dosage in humans.[24][20] As such, the evidence and scientific literature do not support the use of compounded BHT, with or without hormone-level testing, over CHT.[24][21][25][26][22][27][20]

Conversely, the use of approved bioidentical pharmaceutical hormones, namely transdermal or vaginal estradiol and oral or vaginal progesterone, over animal-derived and synthetic hormones, like oral CEEs and oral MPA, is associated with various health advantages.[28][29][30][20][31][32][33][34][23][35] Such advantages include reduced or no risk of venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer, among others.[28][29][30][20][31][32][33][34][23][35] However, less research has been conducted on bioidentical hormones relative to non-bioidentical oral hormonal medications, and there is a need for more clinical research to fully delineate some of these health advantages.[28][29][30][20][31][32][33][34][23][35] In any case, as of 2012, guidelines from the North American Menopause Society, the Endocrine Society, the International Menopause Society, and the European Menopause and Andropause Society all contain positive statements in regards to the management of menopausal women with a personal or family history of venous thromboembolism with transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone over other approaches.[31]

Institutions and organizations such as the FDA have taken public stances on compounded BHT. The FDA has stated that compounded BHT is unsupported by medical evidence, and its administration is considered false and misleading by the agency. The FDA has expressed concern that unfounded claims of compounded hormones having advantages over CHT mislead women and health care professionals. The approved pharmaceutical preparations used in conventional therapy have been researched to quantify these risks and benefits, and are produced by manufacturers with stringent purity and potency standards.[36]

Compounding in the United Kingdom is a regulated activity. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) regulates compounding performed under a Manufacturing Specials license and the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) regulates compounding performed within a pharmacy. All testosterone prescribed in the United Kingdom is bioidentical and its use is supported by the National Health Service (NHS). Marketing authorization exists for male testosterone products. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline 1.4.8 states: "consider testosterone supplementation for menopausal women with low sexual desire if HRT alone is not effective". The footnote adds: "at the time of publication (November 2015), testosterone did not have a United Kingdom marketing authorisation for this indication in women. Bio-identical progesterone is used in IVF treatment and for pregnant women who are at risk of premature labour."

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications

- Undiagnosed vaginal bleeding

- Severe liver disease

- Pregnancy

- Coronary artery disease

- Well-differentiated and early endometrial cancer (once treatment for the malignancy is complete, is no longer an absolute contraindication). Progestogens alone may relieve symptoms if the patient is unable to tolerate estrogens.

- Recent deep vein thrombosis or stroke

Relative contraindications

- Migraine headaches

- Personal history of breast cancer

- Personal history of ovarian cancer

- Venous thrombosis

- History of uterine fibroids

- Atypical ductal hyperplasia of the breast

- Active gallbladder disease (cholangitis, cholecystitis)

Side effects

|

|

Health effects

A 2017 pooled analysis of data from five observational cohort studies in Swedish women found a reduction in risk of stroke among women who started hormone replacement therapy within five years of onset of menopause.[38] Demographically, the vast majority of data available is in postmenopausal American women with concurrent pre-existing conditions, and with a mean age of over 60 years.[39]

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2016 annual meeting mentioned that HRT may have more benefits than risks when it comes to females under the age of 60 years old.[40]

In 2002 the WHI was published. That study looked at the effects of hormonal replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. Both age groups had a slightly higher incidence of breast cancer, and both heart attack and stroke were increased in older patients, although not in younger participants. In fact, the use of HRT in the United States has actually dropped greatly since 2002.[41] Breast cancer was increased in women treated with estrogen and a progestin, but not with estrogen and progesterone or estrogen alone.[42][43][44] Treatment with unopposed estrogen (i.e., an estrogen alone without a progestogen) is contraindicated if the uterus is still present, due to its proliferative effect on the endometrium. The WHI also found a reduced incidence of colorectal cancer when estrogen and a progestogen were used together, and most importantly, a reduced incidence of bone fractures. Ultimately, the study found disparate results for all cause mortality with HRT, finding it to be lower when HRT was begun during ages 50–59, but higher when begun after age 60.[7] Some findings of the WHI were reconfirmed in a larger national study done in the United Kingdom, known as MWS. Coverage of the WHI findings led to a reduction in the number of postmenopausal women on HRT.[45] The authors of the study recommended that women with non-surgical menopause take the lowest feasible dose of HRTHRT, and for the shortest possible time, to minimize risk.[7]

The data published by the WHI suggested supplemental estrogen increased risk of venous emboli and breast cancer but was protective against osteoporosis and colorectal cancer, while the impact on cardiovascular disease was mixed.[46] These results were later confirmed in trials from the United Kingdom, but not in more recent studies from France and China. Genetic polymorphism appears to be associated with inter-individual variability in metabolic response to HRT in postmenopausal women.[47][48]

These recommendations have not held up with further data analysis, however. Subsequent findings released by the WHI showed that all cause mortality was not dramatically different between the groups receiving CEEs, those receiving estrogen and a progestogen, and those not on HRT at all. Specifically, the relative risk for all-cause mortality was 1.04 (confidence interval 0.88–1.22) in the CEEs-alone trial and 1.00 (CI, 0.83–1.19) in the estrogen plus progestogen trial.[49] Further, in analysis pooling data from both trials, postmenopausal HRT was associated with a significant reduction in mortality (RR, 0.70; CI, 0.51–0.96) among women ages 50 to 59. This would represent five fewer deaths per 1,000 women per 5 years of therapy.

However, neither the WHI nor the MWS differentiated the results for different types of progestogens used. MPA – the type most commonly used in the United States – was the only one examined by the WHI, which in its analysis and conclusions extrapolated the benefits versus risks of MPA to all progestins. This conclusion has since been challenged by several researchers as unjustified and misleading, resulting in unreasonable, unnecessary avoidance by many women of HRT. In fact, primate research indicates that the side effects of MPA may be worse than those of other progestogens, and some human studies indicate that MPA may be responsible for negating the protective cardiac benefits of estrogen that were found for estrogen-only HRT users. Critics including Bethea note that there are now research papers showing significantly better outcomes in brain, breast, and cardiovascular parameters with estradiol plus progesterone instead of MPA and conclude that further studies are needed to know more precisely what the differences in effects are when other progestins are used versus bioidentical progesterone in HRT, so that women aren't needlessly discouraged from seeking HRT.[50][51][52][53]

A robust Bayesian meta-analysis from 19 randomized clinical trials reported similar data with a RR of mortality of 0.73 (CI, 0.52–0.96) in women younger than age 60.[54] However, HRT had minimal effect among those between 60 and 69 years of age (RR, 1.05; CI, 0.87–1.26) and was associated with a borderline significant increase in mortality in those between 70 and 79 years of age (RR, 1.14; CI, 0.94 –1.37; P for trend < 0.06).[55] Similarly, in the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) trial, with participants having a mean age of 66.7 yr, HRT did not reduce in total mortality (RR, 1.08; CI, 0.84 –1.38).[56] A 2003 meta-analysis of 30 randomized trials of HRT in relation to mortality showed that it was associated with a nearly 40% reduction in mortality in trials in which participants had a mean age of less than 60 yr or were within 10 yr of menopause onset but was unrelated to mortality in the other trials.[57] The findings in the younger age groups were similar to those in the observational Nurses' Health Study (RR for mortality, 0.63; CI, 0.56 – 0.70).[13][58]

The beneficial potential of HRT was bolstered in a consensus expert opinion published by The Endocrine Society, which stated that when taken during perimenopause or the initial years of menopause, hormonal therapy carries significantly fewer risks than previously published and reduces all cause mortality in most patient scenarios.[13] The AACE released a position statement in 2009 that approved of HRT in the appropriate clinical scenario.

Proprietary mixtures of progestins and CEEs are a commonly prescribed form of HRT. As the most common and longest-prescribed type of estrogen used in HRT, most studies of HRT involve CEEs. More recently developed forms of drug delivery include suppositories, subdermal implants, skin patches and gels. They have more local effect, lower doses, fewer side effects, and result in constant rather than cyclical serum hormone levels.[59]

| Event | Relative Risk CEEs/MPA vs. placebo at 5.2 years (95% CI*) | Placebo (n = 8102) | CEEs/MPA (n = 8506) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Risk per 10,000 Women-Years | |||||||||

| Coronary heart disease events Non-fatal myocardial infarction Coronary heart disease death | 1.29 (1.02–1.63) 1.32 (1.02–1.72) 1.18 (0.70–1.97) | 30 23 6 | 37 30 7 | ||||||

| Invasive breast cancera | 1.26 (1.00–1.59) | 30 | 38 | ||||||

| Stroke | 1.41 (1.07–1.85) | 21 | 29 | ||||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 2.13 (1.39–3.25) | 8 | 16 | ||||||

| Colorectal cancer | 0.63 (0.43–0.92) | 16 | 10 | ||||||

| Endometrial cancer | 0.83 (0.47–1.47) | 6 | 5 | ||||||

| Hip fracture | 0.66 (0.45–0.98) | 15 | 10 | ||||||

| Death due to causes other than above | 0.92 (0.74–1.14) | 40 | 37 | ||||||

| Global Indexb | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) | 151 | 170 | ||||||

| Deep vein thrombosisc | 2.07 (1.49–2.87) | 13 | 26 | ||||||

| Vertebral fracturesc | 0.66 (0.44–0.98) | 15 | 9 | ||||||

| Other osteoporotic fracturesc | 0.77 (0.69–0.86) | 170 | 131 | ||||||

| WHI = Women's Health Initiative. CEEs = Conjugated estrogens. MPA = Medroxyprogesterone acetate. a = Includes metastatic and non-metastatic breast cancer with the exception of in situ breast cancer. b = A subset of the events was combined in a "global index", defined as the earliest occurrence of coronary heart disease events, invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, hip fracture, or death due to other causes. c = Not included in Global Index. * = Nominal confidence intervals unadjusted for multiple looks and multiple comparisons. Sources:[60][61] | |||||||||

Sexual dysfunction

Menopause is the permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from loss of ovarian follicular activity.[5] Menopause can be divided into early and late transition periods, also known as perimenopause and postmenopause. Each stage is marked by changes in hormonal patterns, which can induce menopausal symptoms.[5] It is possible to induce menopause prematurely by surgically removing the ovary or ovaries (oophorectomy). This is often done as a consequence of ovarian failure, such as ovarian or uterine cancers. The most common side effects of the menopausal transition are: lack of sexual desire or libido, lack of sexual arousal, and vaginal dryness.[5] The modification of women’s physiology can lead to changes in her sexual response, the development of sexual dysfunctions, and changes in her levels of sexual desire.[62]

It is commonly perceived that once women near the end of their reproductive years and enter menopause that this equates to the end of her sexual life.[5] However, especially since women today are living one third or more of their lives in a postmenopausal state, maintaining, if not improving, their quality of life, of which their sexuality can be a key determinant, is of importance.[63] A recent study of sexual activities among women aged 40–69 revealed that 75% of women are sexually active at this age; this indicates that the sexual health and satisfaction of menopausal women are an aspect of sexual health and quality of life that is worthy of attention by health care professionals.[5]

A major complaint among postmenopausal women is decreased libido, and many may seek medical consultation for this.[6] Several hormonal changes take place during the menopausal period, including a decrease in estrogen levels and an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone. For most women, the majority of change occurs during the late perimenopausal and postmenopausal stages.[5] Decrease in other hormones such as the sex hormone-binding globulim (SHBG) and inhibin (A and B) also take place in the postmenopausal period. Testosterone, a hormone more commonly associated with males, is also present in women. It peaks at age 30, but declines with age, so there is little variation across the lifetime and during the menopausal transition.[5] However, in surgically induced menopause, instead of the levels of estrogens and testosterone slowly declining over time, they decline very sharply, resulting in more severe symptoms.[5]

In menopausal women, sexual functioning can impact several dimensions of a woman’s life, including her physical, psychological, and mental well-being.[64] During the onset of menopause, sexuality can be a critical issue in determining whether one begins to experience changes in their sexual response cycle.[65] Both age — and menopause-related events can affect the integrity of a woman’s biological systems involved in the sexual response cycle, which include hormone environment, neuro-muscular substrates, and vascular supplies.[65] Therefore, it can be appropriate to make use of HRT, especially in women with low or declining quality of life due to sexual difficulties.[6]

Current research that has examined the impact of menopause on women’s self-reported sexual satisfaction indicates that 50.3% of women experience some sexual disturbance in one of five domains, and 33.7% experience disturbances in two of the domains.[64] Of these were desire, orgasm, lubrication, and arousal disturbances. With regards to arousal, they found a significant negative association between age and arousal, in that as women aged they were more likely to report lower arousal scores. In the desire and orgasm domains, 38% of women reported a disturbances in their desire, and 17% reported a disturbance in their orgasm capabilities; of the 17%, 14% were premenopausal, 15.2% were postmenopausal and taking a form of HRT, and 22% were postmenopausal not on a form of HRT.[64] Eight percent of women reported disturbances lubricating during sexual activity; 14.3% in the premenopausal group, 30% in the postmenopausal group not using a HRT, and 11.7% among those postmenopausal women using HRT.[64] Lastly, 21% of women reported pain as a disturbance in their sexual satisfaction — the premenopausal group at 14.3%, the postmenopausal women using HRT at 13.3% and the group with the highest rates, similarly to the other results, was the postmenopausal women not taking HRT at 34%.[64] This study concluded that there was a significant decline in sexual function related to menopause in the pain and lubrication domains.[64]

The maintenance and improvement of quality of life during the menopausal period is at the core of estrogen and progestogen-based HRT.[6] Both HRT and estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) have been shown to enhance sexual desire in a significant percent of women; however, as with all pharmacological treatments, not all women have been responsive, especially those with preexisting sexual difficulties.[62] ERT restores vaginal cells, pH levels, and blood flow to the vagina, all of which deterioration are associated with the onset of menopause. Dyspareunia (due to vaginal dryness) appears to be the most responsive component of menopausal women’s sexuality to ERT.[62] It also has been shown to have positive effects on the urinary tract and atrophy and may initially improve libido or sexual sensitivity.[62] Other improvements in areas such as sexual desire, arousal, fantasies, and frequency of coitus and orgasm have also been noted.[62] However, the effectiveness of ERT has been shown to decline in some women after long-term use.[62] A number of studies have found that the combined effects of estrogen/androgen replacement therapy can increase a woman’s motivational aspects of sexual behaviour over and above what can be achieved with estrogen therapy alone.[62] Findings on a relatively new form of HRT called tibolone — a synthetic steroid with estrogenic, androgenic, and progestogenic properties — suggest that it has the ability to improve mood, libido, and somatic symptoms of surgically menopausal women to a greater degree than ERT. In various placebo-controlled studies, improvements in vasomotor symptoms, emotional reactions, sleep disturbances, somatic symptoms, and sexual desire have been observed.[6] However, while this is and has been available in Europe for almost two decades, this has not been approved for use in North America at this point.[6]

The goal of HRT is to mitigate discomfort caused by diminished circulating estradiol and progesterone in menopause. In those with premature or surgically induced menopause, a combination HRT is often recommended, as it may also prolong life and may decrease a woman's chances of developing endometrial cancers associated with unopposed estrogen therapy, as well by decreasing the incidence of dementia.[4][5] The main hormones involved are estrogens and progestogens. Some recent therapies include the use of androgens as well.[6]

Data from numerous studies have consistently found that HRT leads to improvements in aspects of postmenopausal sexual dysfunction.[6] Sexuality is a critical aspect of quality of life for the large majority of menopausal women; therefore, any features of the menopausal transition that can negatively affect a woman’s sexuality have the ability to significantly alter her quality of life. The most prevalent of female sexual dysfunctions linked to menopause include lack of desire and low libido, both of which can be explained by changes in hormonal physiology.[5]

Improvements in sexual pain, vaginal lubrication and orgasm are found to be statistically different from those using HRT.[5] Estrogens have positive effects of mood, sexual function, target end organs, and cognitive function.

Venous and arterial coagulation

Comparisons between orally administered pill and transdermal patch suggests that when estrogens are taken orally the risks of thrombophlebitis and pulmonary embolism are increased, an effect which is not seen with topical administration. Transdermal and transvaginal administration are not subject to first pass metabolism, and so lack the anabolic effects that oral therapy has on hepatic synthesis of Vitamin K dependent clotting factors.[66] This effect refers only to patches for HRT, which contain estradiol, not those used in oral contraceptive therapy, which contain ethinylestradiol. The latter is associated with an increased incidence of venous clot.[67] The WHI also showed an increased incidence arterial disease, namely stroke, in patients who began HRT after the age of 65, although this effect was not significantly present in those who began therapy during their fifth decade.

Cardiovascular effects

The impact of HRT on cardiovascular morbidity is a subject of much controversy in the medical literature. The reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases associated with HRT, reported in observational studies, has not been subsequently confirmed in randomized clinical trials. The increased risk of cardiovascular disease in the WHI was not statistically significant, and only found in the oldest women, and those who started HRT late after menopause began.[68] The increase in risks of coronary heart disease in the treatment arm of the study varied according to age and years since onset of menopause. Women aged 50 to 59 using HRT showed a trend towards lower risk of coronary heart disease,[69] as did women who were within five years of the onset of menopause.[70]

A Cochrane review came to the result that in women starting HRT less than 10 years after menopause have a lower mortality and lower rate of coronary heart disease compared to placebo or no treatment, without any strong evidence of an effect on the risk of stroke. Those starting therapy more than 10 years after menopause have little effect on mortality and coronary heart disease, but have an increased risk of stroke. Overall, however, taking the increased risk of venous thromboembolism into account, it came to the conclusion that has HRT has little if any benefit for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.[71]

The adverse cardiovascular outcomes may only apply to oral dosing with CEEs and progestins in oral systemic therapy, while transdermal estradiol and estriol may not produce the same risks, due to the absence of anabolic effects of hepatic vitamin K dependent clotting factors.[67]

On a molecular level, HRT at the time of menopause has effects on the lipid profile. Specifically, HDL decreases, while LDL, triglycerides and lipoprotein a increase. Supplemental estrogen improves the lipid profile by reversing each of these effects. Beyond this, it improves cardiac contractility, coronary artery blood flow, metabolism of carbohydrates, and decreases platelet aggregation and plaque formation. At the molecular level HRT may promote reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) via the induction of cholesterol ABC transporters.[72]

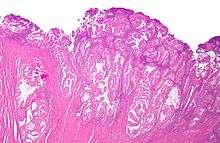

Endometrial effects

While combined estrogen–progestogen supplementation has been linked to an increased incidence of endometrial cancer, the specific subtype is usually stage I, or in situ, and has extremely low morbidity and mortality, and studies in American women have shown the tumor to not have propensity for growth into the myometrium or parametrial soft tissues. When seen in the context of all cause mortality, women who take estrogen and develop endometrial cancer have higher survival rates than women who do not take hormonal therapy at all, which was due to the preventive effect of HRT on hip fractures.

Unopposed estrogen can also result in endometrial hyperplasia, a precursor to endometrial cancer. The extensive use of high-dose estrogens for birth control in the 1970s is thought to have resulted in a significant increase in the incidence of this type of cancer.[73]

Musculoskeletal effects

HRT is effective at reversing the effects of aging on muscle.[74]

Neurologic effects

According to a 2007 presentation at an American Academy of Neurology meeting,[75] HRT taken soon after menopause may help protect against dementia, but it raises the risk of mental decline in women who do not take HRT until they are older. Dementia risk was 1% in women who started HRT early, and 1.7% in women who didn't, (i.e. women who didn't take HRT seem to have had — on average — a 70% higher relative risk of dementia than women who began HRT around the time of the beginning of menopause). This suggests that there may be a "critical period" during which time taking HRT may have benefits, but if HRT is initiated after that period, it will not have such benefits and may cause harm. This is consistent with research that HRT improves executive and attention processes in postmenopausal women.[76] It is also supported by research upon monkeys that were given ovariectomies to imitate the effect of menopause and then estrogen therapies. This showed replacement treated compared to nontreated monkeys had long term improved prefrontal cortex executive abilities on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.[77]

Breast tissue effects

The relative risk (RR) of breast cancer varies from 1.24 in the WHI study to 1.66 in the MWS, with results differing according to interval between menopause and HRT and methods of HRT.[78] The WHI preliminary results in 2004 found a non-significant trend in the estrogen-alone clinical trial towards a reduced risk of breast cancer[69] and a 2006 update concluded that use of estrogen-only HRT for 7 years does not increase the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women who have had a hysterectomy.[79] The results of the WHI estrogen-alone trial suggest that the progestin used in the WHI estrogen-plus-progestin trial increased the risk for breast cancer above that associated with estrogen alone.[80] HRT has been more strongly associated with risk of breast cancer in women with low or normal body mass index (BMI) of less than 25, but no association has been observed in women with a high body mass index.[81]

Research has found that increased breast cancer risk applies only to those women who take progestins, but not to those taking bioidentical progesterone itself, nor to hysterectomized women who take estrogen alone.[82] It has been suggested by some that the absence of effect in these studies could be due to selective prescription to overweight women, or to the very low progesterone serum levels after oral administration leading to a strong tumor inactivation rate.[83]

For women who previously have had breast cancer, it is recommended to first consider other options for menopausal effects, such as bisphosphonates or selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for osteoporosis, cholesterol-lowering agents and aspirin for cardiovascular disease, and vaginal estrogen for local symptoms. Observational studies of systemic HRT after breast cancer are generally reassuring. If HRT is necessary after breast cancer, estrogen-only therapy or estrogen therapy with a progestogen may be safer options than combined systemic therapy.[84]

Hip fractures

Estrogen prevents the activity of osteoclasts, and improves bone mineral density. Hip fracture is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in older females, and usually does not occur in the setting of osteoporosis. Estrogen is the only medical therapy that has been shown to prevent hip fractures in women that are not osteoporotic, with efficacy superior to bisphosphonates or calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Ovarian cancer

A 2015 meta-analysis found that HRT was associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer. The authors concluded that if this association is causal, women using HRT have about one additional case of ovarian cancer per 1,000 users.[85]

Epigenetic aging effects

HRT appears to slow down the biological/epigenetic aging rate of buccal cells but not that of blood cells.[86] Conversely, the unmitigated loss of hormones resulting from menopause accelerates the biological aging rate of blood [86] according to a molecular biomarker of aging known as epigenetic clock.[87]

History

The extraction of CEEs from the urine of pregnant mares led to the marketing in 1942 of Premarin, one of the earlier forms of estrogen to be introduced.[88][89] From that time until the mid-1970s, estrogen was administered without a supplemental progestogen. Studies in the 1975 and thereafter demonstrated that in the absence of a progestogen, unopposed estrogen therapy with Premarin resulted in an 8-fold increased risk of endometrial cancer.[88] After this, sales of Premarin plummeted for a few years.[88] However, it was shown by the early 1980s that the addition of a progestogen to estrogen therapy could mitigate the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in women with intact uteruses.[88] This led to the development of combined estrogen–progestogen therapy who had not undergone hysterectomy, most typically with a combination of Premarin and Provera (CEEs and MPA, respectively), and in the birth of the modern concept of what is referred to as "hormone replacement therapy".[88]

The WHI trials were conducted between 1991 and 2004.[88] However, the arm of the WHI receiving combined estrogen and progestin therapy was closed prematurely in 2002 by its Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) due to perceived health risks, although the trial arm was stopped only a full year after the data suggesting increased risk became manifest. In 2004, the arm of the WHI in which post-hysterectomy patients were being treated with estrogen alone was also closed by the DMC.

Women's Health Initiative

Clinical medical practice changed based upon two parallel Women's Health Initiative (WHI) studies of HRT. Prior studies were smaller, and many were of women who electively took hormonal therapy. The WHI studies were the first large, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of HRT in healthy women.

One portion of the parallel studies followed over 16,000 women for an average of 5.2 years, half of whom took placebo, while the other half took a combination of CEEs and MPA (Prempro).

This WHI estrogen-plus-progestin trial was stopped prematurely in 2002 because preliminary results suggested risks of combined CEEs and progestins exceeded their benefits. The first report on the halted WHI estrogen-plus-progestin study came out in July 2002.[7]

The study reported statistically significant increases in rates of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, strokes and pulmonary emboli. The study also found statistically significant decreases in rates of hip fracture and colorectal cancer. "A year after the study was stopped in 2002, an article was published indicating that estrogen plus progestin also increases the risks of dementia."[90] The conclusion of the study was that the HRT combination presented risks that outweighed its measured benefits. The results were almost universally reported as risks and problems associated with HRT in general, rather than with Prempro, the specific proprietary combination of CEEs and MPA studied.

After the increased clotting found in the first WHI results was reported in 2002, the number of Prempro prescriptions filled reduced by almost half. Following the WHI results, a large percentage of HRT users opted out of them, which was quickly followed by a sharp drop in breast cancer rates. The decrease in breast cancer rates has continued in subsequent years.[91] An unknown number of women started taking alternatives to Prempro, such as compounded bioidentical hormones, though researchers have asserted that compounded hormones are not significantly different from conventional hormone therapy.[92]

The other portion of the parallel studies featured women who were post hysterectomy so who consequently did not need to take a progestogen when using estrogen. They were given either placebo or CEEs alone. This group did not show the risks demonstrated in the combination hormone study, and the estrogen-only study was not halted in 2002. However, in February 2004 it, too, was halted. While there was a 23% decreased incidence of breast cancer in the estrogen-only study participants, risks of stroke and pulmonary embolism were increased slightly, predominantly in patients who began HRT over the age of 60.[93]

The WHI trial was limited by low adherence, high attrition, inadequate power to detect risks for some outcomes, and evaluation of few regimens.[11] The double blinding limited validity of study results due to its effects on patient exclusion criteria. Patients who were experiencing symptoms of the menopausal transition were excluded from the study, meaning that younger women who had only recently experienced menopause were not significantly represented. As a result, while the average age of menopause is age 51, study participants were on average 62 years of age. Demographically, the vast majority were Caucasian, and tended to be slightly overweight and former smokers.

Society and culture

Wyeth controversy

Wyeth, now a subsidiary of Pfizer, was a pharmaceutical company that marketed the HRT products Premarin (CEEs) and Prempro (CEEs + MPA).[94][95] In 2009, litigation involving Wyeth resulted in the release of 1,500 documents that revealed practices concerning its promotion of these medications.[94][95][96] The documents showed that Wyeth commissioned dozens of ghostwritten reviews and commentaries that were published in medical journals in order to promote unproven benefits of its HRT products, downplay their harms and risks, and cast competing therapies in a negative light.[94][95][96] Starting in the mid-1990s and continuing for over a decade, Wyeth pursued an aggressive "publication plan" strategy to promote its HRT products through the use of ghostwritten publications.[96] It worked mainly with DesignWrite, a medical writing firm.[96] Between 1998 and 2005, Wyeth had 26 papers promoting its HRT products published in scientific journals.[94]

These favorable publications emphasized the benefits and downplayed the risks of its HRT products, especially the "misconception" of the association of its products with breast cancer.[96] The publications defended unsupported cardiovascular "benefits" of its products, downplayed risks such as breast cancer, and promoted off-label and unproven uses like prevention of dementia, Parkinson's disease, vision problems, and wrinkles.[95] In addition, Wyeth emphasized negative messages against the SERM raloxifene for osteoporosis, instructed writers to stress the fact that "alternative therapies have increased in usage since the WHI even though there is little evidence that they are effective or safe...", called into question the quality and therapeutic equivalence of approved generic CEE products, and made efforts to spread the notion that the unique risks of CEEs and MPA were a class effect of all forms of menopausal HRT: "Overall, these data indicate that the benefit/risk analysis that was reported in the Women's Health Initiative can be generalized to all postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy products."[95]

In any case, following the publication of the WHI data in 2002, the stock prices for the pharmaceutical industry plummeted, and huge numbers of women stopped using HRT.[97] The stocks of Wyeth, which supplied the Premarin and Prempro that were used in the WHI trials, decreased by more than 50%, and never fully recovered.[97] After the publication of the WHI data, Wyeth and other pharmaceutical companies commissioned ghostwritten publications that downplayed the findings of the trials.[88] These articles promoted themes such as the following: "the WHI was flawed; the WHI was a controversial trial; the population studied in the WHI was inappropriate or was not representative of the general population of menopausal women; results of clinical trials should not guide treatment for individuals; observational studies are as good as or better than randomized clinical trials; animal studies can guide clinical decision-making; the risks associated with hormone therapy have been exaggerated; the benefits of hormone therapy have been or will be proven, and the recent studies are an aberration."[88] Similar findings were observed in a 2010 analysis of 114 editorials, reviews, guidelines, and letters by five industry-paid authors.[88] These publications promoted positive themes and challenged and criticized unfavorable trials such as the WHI and MWS.[88] In 2009, Wyeth was acquired by Pfizer in a deal valued at US$68 billion.[98][99] Pfizer, a company that produces Provera and Depo-Provera (MPA) and has also engaged in medical ghostwriting, continues to market Premarin and Prempro, which remain best-selling medications.[88][96]

According to Fugh-Berman (2010), "Today, despite definitive scientific data to the contrary, many gynecologists still believe that the benefits of [HRT] outweigh the risks in asymptomatic women. This non-evidence–based perception may be the result of decades of carefully orchestrated corporate influence on medical literature."[95] Indeed, as many as 50% of physicians have expressed skepticism to the results of large trials like the WHI and HERS.[100] The positive perceptions of many physicians of HRT in spite of large trials showing risks that potentially outweigh any benefits may be due to the efforts of pharmaceutical companies like Wyeth.[96][88]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, Lumsden MA, Murad MH, Pinkerton JV, Santen RJ (November 2015). "Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100 (11): 3975–4011. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2236. PMID 26444994.

- 1 2 3 Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, Archer DF, Boyd N, Braunstein GD, Burger HG, Colditz GA, Davis SR, Gambacciani M, Gower BA, Henderson VW, Jarjour WN, Karas RH, Kleerekoper M, Lobo RA, Manson JE, Marsden J, Martin KA, Martin L, Pinkerton JV, Rubinow DR, Teede H, Thiboutot DM, Utian WH (July 2010). "Postmenopausal hormone therapy: an Endocrine Society scientific statement". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95 (7 Suppl 1): s1–s66. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2509. PMID 20566620.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- 1 2 Shuster, Lynne T.; Rhodes, Deborah J.; Gostout, Bobbie S.; Grossardt, Brandon R.; Rocca, Walter A. (2010). "Premature menopause or early menopause: Long-term health consequences". Maturitas. 65 (2): 161–166. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.08.003. ISSN 0378-5122. PMC 2815011. PMID 19733988.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Eden, K.J., & Wylie, K.R. (2009). Quality of sexual life and menopause. Women’s Health, 5 (4), 385-396. doi:10.2217/whe.09.24

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ziaei, S., Moghasemi, M., & Faghihzadeh, S. (2010). Comparative effects of conventional hormone replacement therapy and tibolone on climacteric symptoms and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Climateric, 13, 147-156. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.04.014

- 1 2 3 4 5 Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators (2002). "Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: Principal Results From the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial". JAMA. 288 (3): 321–333. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321. PMID 12117397.

- ↑ Chlebowski RT, Kuller LH, Prentice RL, Stefanick ML, Manson JE, Gass M, et al. (February 2009). "Breast cancer after use of estrogen plus progestin in postmenopausal women". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (6): 573–87. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807684. PMC 3963492. PMID 19196674.

- ↑ "USPTF Consensus Statement". 2012.

- ↑ Kreatsoulas, C.; Anand, S. S. (2013). "Menopausal hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement" (pdf). Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 123 (3): 112–117. PMID 23396275.

- 1 2 Nelson, H. D.; Walker, M.; Zakher, B.; Mitchell, J. (2012). "Menopausal hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions: A systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (2): 104–113. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00466. PMID 22786830.

- ↑ Grossman, David C.; Curry, Susan J.; Owens, Douglas K.; Barry, Michael J.; Davidson, Karina W.; Doubeni, Chyke A.; Epling, John W.; Kemper, Alex R.; Krist, Alex H.; Kurth, Ann E.; Landefeld, C. Seth; Mangione, Carol M.; Phipps, Maureen G.; Silverstein, Michael; Simon, Melissa A.; Tseng, Chien-Wen (12 December 2017). "Hormone Therapy for the Primary Prevention of Chronic Conditions in Postmenopausal Women". JAMA. 318 (22): 2224. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.18261. PMID 29234814.

- 1 2 3 Santen, RJ; Utian, WH (2010). "Executive Summary: Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 95 S1–S66 (Supplement 1): s1–s66. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2509. Retrieved Jan 16, 2015.

- ↑ Raine-Fenning NJ, Brincat MP, Muscat-Baron Y (2003). "Skin aging and menopause : implications for treatment". Am J Clin Dermatol. 4 (6): 371–8. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304060-00001. PMID 12762829.

- ↑ Zouboulis CC, Makrantonaki E (June 2012). "Hormonal therapy of intrinsic aging". Rejuvenation Res. 15 (3): 302–12. doi:10.1089/rej.2011.1249. PMID 22533363.

- ↑ "Menopause treatments". NHS. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ Morley JE, Perry HM (May 2003). "Androgens and women at the menopause and beyond". J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 58 (5): M409–16. doi:10.1093/gerona/58.5.M409. PMID 12730248.

- ↑ Garefalakis M, Hickey M (2008). "Role of androgens, progestins and tibolone in the treatment of menopausal symptoms: a review of the clinical evidence". Clin Interv Aging. 3 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2147/CIA.S1043. PMC 2544356. PMID 18488873.

- ↑ Estrogen (Vaginal Route) from Mayo Clinic / Thomson Healthcare Inc. Portions of this document last updated: Nov. 1, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Conaway E (March 2011). "Bioidentical hormones: an evidence-based review for primary care providers". J Am Osteopath Assoc. 111 (3): 153–64. PMID 21464264.

- 1 2 Cirigliano M (June 2007). "Bioidentical hormone therapy: a review of the evidence". J Womens Health (Larchmt). 16 (5): 600–31. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0311. PMID 17627398.

- 1 2 L'Hermite M (June 2017). "Custom-compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: why so popular despite potential harm? The case against routine use". Climacteric. 20 (3): 205–211. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1285277. PMID 28509626.

- 1 2 3 4 L'Hermite M (August 2017). "Bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy: registered hormones (non-oral estradiol ± progesterone) are optimal". Climacteric. 20 (4): 331–338. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1291607. PMID 28301216.

- 1 2 Boothby LA, Doering PL, Kipersztok S (2004). "Bioidentical hormone therapy: a review". Menopause. 11 (3): 356–67. doi:10.1097/01.GME.0000094356.92081.EF. PMID 15167316.

- ↑ Sites CK (March 2008). "Bioidentical hormones for menopausal therapy". Womens Health (Lond). 4 (2): 163–71. doi:10.2217/17455057.4.2.163. PMID 19072518.

- ↑ Davis R, Batur P, Thacker HL (August 2014). "Risks and effectiveness of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: a case series". J Womens Health (Larchmt). 23 (8): 642–8. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4770. PMID 25111856.

- ↑ Taylor M (December 2001). "Unconventional estrogens: estriol, biest, and triest". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 44 (4): 864–79. doi:10.1097/00003081-200112000-00024. PMID 11600867.

- 1 2 3 L'hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, Genazzani AR (2008). "Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review". Maturitas. 60 (3–4): 185–201. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.07.007. PMID 18775609.

- 1 2 3 Holtorf K (January 2009). "The bioidentical hormone debate: are bioidentical hormones (estradiol, estriol, and progesterone) safer or more efficacious than commonly used synthetic versions in hormone replacement therapy?". Postgrad Med. 121 (1): 73–85. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.01.1949. PMID 19179815.

- 1 2 3 Buster JE (June 2010). "Transdermal menopausal hormone therapy: delivery through skin changes the rules". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 11 (9): 1489–99. doi:10.1517/14656561003774098. PMID 20426703.

- 1 2 3 4 Simon JA (April 2012). "What's new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone". Climacteric. 15 Suppl 1: 3–10. doi:10.3109/13697137.2012.669332. PMID 22432810.

- 1 2 3 Mueck AO (April 2012). "Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone". Climacteric. 15 Suppl 1: 11–7. doi:10.3109/13697137.2012.669624. PMID 22432811.

- 1 2 3 L'Hermite M (August 2013). "HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT". Climacteric. 16 Suppl 1: 44–53. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.808563. PMID 23848491.

- 1 2 3 Simon JA (July 2014). "What if the Women's Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead?". Menopause. 21 (7): 769–83. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000169. PMID 24398406.

- 1 2 3 Davey DA (March 2018). "Menopausal hormone therapy: a better and safer future". Climacteric: 1–8. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1439915. PMID 29526116.

- ↑ "FDA Takes Action Against Compounded Menopause Hormone Therapy Drugs". FDA. 2008-01-09. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ↑ Suchowersky O, Muthipeedika J (December 2005). "A case of late-onset chorea". Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 1 (2): 113–6. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0052. PMID 16932507.

- ↑ Carrasquilla GD, Frumento P, Berglund A, Borgfeldt C, Bottai M, Chiavenna C, Eliasson M, Engström G, Hallmans G, Jansson JH, Magnusson PK, Nilsson PM, Pedersen NL, Wolk A, Leander K (November 2017). "Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of stroke: A pooled analysis of data from population-based cohort studies". PLoS Med. 14 (11): e1002445. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002445. PMC 5693286. PMID 29149179.

- ↑ Marjoribanks, Jane; Farquhar, Cindy; Roberts, Helen; Lethaby, Anne; Lee, Jasmine (17 Jan 2017). "Long-term hormone therapy for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD004143. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004143.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 28093732.

- ↑ "Medscape". www.medscape.com.

- ↑ "Hormone therapy for brain performance: No effect, whether started early or late". www.sciencedaily.com.

- ↑ Yang Z, Hu Y, Zhang J, Xu L, Zeng R, Kang D (February 2017). "Estradiol therapy and breast cancer risk in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 33 (2): 87–92. doi:10.1080/09513590.2016.1248932. PMID 27898258.

- ↑ Lambrinoudaki I (April 2014). "Progestogens in postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer". Maturitas. 77 (4): 311–7. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.01.001. PMID 24485796.

- ↑ Sturdee DW (August 2013). "Are progestins really necessary as part of a combined HRT regimen?". Climacteric. 16 Suppl 1: 79–84. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.803311. PMID 23651281.

- ↑ Chlebowski, R. T.; Kuller, L. H.; Prentice, R. L.; Stefanick, M. L.; Manson, J. E.; Gass, M.; Aragaki, A. K.; Ockene, J. K.; Lane, D. S.; Sarto, G. E.; Rajkovic, A.; Schenken, R.; Hendrix, S. L.; Ravdin, P. M.; Rohan, T. E.; Yasmeen, S.; Anderson, G.; Whi, I. (2009). "Breast Cancer after Use of Estrogen plus Progestin in Postmenopausal Women". New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (6): 573–587. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807684. PMC 3963492. PMID 19196674.

- ↑ George, James L.; Colman, Robert W.; Goldhaber, Samuel Z.; Victor J. Marder (2006). Hemostasis and thrombosis: basic principles and clinical practice. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1239. ISBN 0-7817-4996-4.

- ↑ Darabi M, Ani M, Panjehpour M, Rabbani M, Movahedian A, Zarean E (2011). "Effect of estrogen receptor β A1730G polymorphism on ABCA1 gene expression response to postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy". Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 15 (1–2): 11–5. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2010.0106. PMID 21117950.

- ↑ Chlebowski, R. T.; Anderson, G. L. (2015). "Menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer mortality: clinical implications". Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 6 (2): 45–56. doi:10.1177/2042098614568300. ISSN 2042-0986. PMC 4406918. PMID 25922653.

- ↑ Rossouw, J. E.; Prentice, R. L.; Manson, J. E.; Wu, L.; Barad, D.; Barnabei, V. M.; Ko, M.; Lacroix, A. Z.; Margolis, K. L.; Stefanick, M. L. (2007). "Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease by Age and Years Since Menopause". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 297 (13): 1465–1477. doi:10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. PMID 17405972.

- ↑ Bethea CL (Feb 2011). "MPA: Medroxy-Progesterone Acetate Contributes to Much Poor Advice for Women". Endocrinology. 152 (2): 343–345. doi:10.1210/en.2010-1376. PMC 3037166. PMID 21252179.

- ↑ Harman SM, Brinton EA, Cedars M, Lobo R, Manson JE, Merriam GR, Miller VM, Naftolin F, Santoro N (March 2005). "KEEPS: The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study". Climacteric. 8 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1080/13697130500042417. PMID 15804727.

- ↑ Langer RD (August 2010). "On the need to clarify and disseminate contemporary knowledge of hormone therapy initiated near menopause". Climacteric. 13 (4): 303–6. doi:10.3109/13697137.2010.496316. PMID 20540591.

- ↑ Studd J (March 2010). "Ten reasons to be happy about hormone replacement therapy: a guide for patients". Menopause Int. 16 (1): 44–6. doi:10.1258/mi.2010.010001. PMID 20424287.

- ↑ Salpeter, S. R.; Cheng, J.; Thabane, L.; Buckley, N. S.; Salpeter, E. E. (2009). "Bayesian Meta-analysis of Hormone Therapy and Mortality in Younger Postmenopausal Women". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (11): 1016–1022.e1. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.021. PMID 19854329.

- ↑ Anderson, G. L.; Chlebowski, R. T.; Rossouw, J. E.; Rodabough, R. J.; McTiernan, A.; Margolis, K. L.; Aggerwal, A.; David Curb, J. D.; Hendrix, S. L.; Allan Hubbell, F. A.; Khandekar, J.; Lane, D. S.; Lasser, N.; Lopez, A. M.; Potter, J.; Ritenbaugh, C. (2006). "Prior hormone therapy and breast cancer risk in the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin". Maturitas. 55 (2): 103–115. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.05.004. PMID 16815651.

- ↑ Hulley, S.; Grady, D.; Bush, T.; Furberg, C.; Herrington, D.; Riggs, B.; Vittinghoff, E. (1998). "Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 280 (7): 605–613. doi:10.1001/jama.280.7.605. PMID 9718051.

- ↑ Salpeter, S. R.; Walsh, J. M. E.; Greyber, E.; Ormiston, T. M.; Salpeter, E. E. (2004). "Mortality associated with hormone replacement therapy in younger and older women". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 19 (7): 791–804. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30281.x. PMC 1492478. PMID 15209595.

- ↑ Grodstein, F.; Stampfer, M. J.; Colditz, G. A.; Willett, W. C.; Manson, J. E.; Joffe, M.; Rosner, B.; Fuchs, C.; Hankinson, S. E.; Hunter, D. J.; Hennekens, C. H.; Speizer, F. E. (1997). "Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Mortality". New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (25): 1769–1775. doi:10.1056/NEJM199706193362501. PMID 9187066.

- ↑ Fraser IS, Mansour D (March 2006). "Delivery systems for hormone replacement therapy". Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 3 (2): 191–204. doi:10.1517/17425247.3.2.191. PMID 16506947.

- ↑ Warner Chilcott (March 2005). "ESTRACE TABLETS, (estradiol tablets, USP)" (PDF). fda.gov. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J (July 2002). "Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 288 (3): 321–33. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321. PMID 12117397.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sarrel, P.M. (2000). Effects of hormone replacement therapy on sexual psychophysiology and behavior in postmenopause. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine, 9, 25-32

- ↑ Miller M.M.; Franklin K.B.J. (1999). "Theoretical basis for the benefit of postmenopausal estrogen substitution". Experimental Gerontology. 34 (5): 587–604. doi:10.1016/S0531-5565(99)00032-7. PMID 10530785.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gonzalez, M., Viagara, G., Caba, F., & Molina, E. (2004). Sexual function, menopause and hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The European Menopause Journal, 48, 411-420. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.10.005

- 1 2 Nappi, R.E. et al., (2006). Clitoral stimulation in postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction: A pilot randomized study with hormone therapy. European Menopause Journal, 55, 288-295

- ↑ Olié, V. R.; Canonico, M.; Scarabin, P. Y. (2010). "Risk of venous thrombosis with oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy among postmenopausal women". Current Opinion in Hematology. 17 (5): 457–463. doi:10.1097/MOH.0b013e32833c07bc. PMID 20601871.

- 1 2 Scarabin, P. Y.; Oger, E.; Plu-Bureau, G. V.; EStrogen THromboEmbolism Risk Study Group (2003). "Differential association of oral and transdermal oestrogen-replacement therapy with venous thromboembolism risk". The Lancet. 362 (9382): 428–432. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14066-4. PMID 12927428.

- ↑ Stramba-Badiale, M. (2009). "Postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of cardiovascular disease". Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 10 (4): 303–309. doi:10.2459/JCM.0b013e328324991c. PMID 19430340.

- 1 2 Anderson, G. L.; Limacher, M.; Assaf, A. R.; Bassford, T.; Beresford, S. A.; Black, H.; Bonds, D.; Brunner, R.; Brzyski, R.; Caan, B.; Chlebowski, R.; Curb, D.; Gass, M.; Hays, J.; Heiss, G.; Hendrix, S.; Howard, B. V.; Hsia, J.; Hubbell, A.; Jackson, R.; Johnson, K. C.; Judd, H.; Kotchen, J. M.; Kuller, L.; Lacroix, A. Z.; Lane, D.; Langer, R. D.; Lasser, N.; Lewis, C. E.; Manson, J. (2004). "Effects of Conjugated Equine Estrogen in Postmenopausal Women with Hysterectomy: The Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 291 (14): 1701–1712. doi:10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. PMID 15082697.

- ↑ Manson, J. E.; Hsia, J.; Johnson, K. C.; Rossouw, J. E.; Assaf, A. R.; Lasser, N. L.; Trevisan, M.; Black, H. R.; Heckbert, S. R.; Detrano, R.; Strickland, O. L.; Wong, N. D.; Crouse, J. R.; Stein, E.; Cushman, M.; Women's Health Initiative Investigators (2003). "Estrogen plus Progestin and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (6): 523–534. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030808. PMID 12904517.

- ↑ Boardman, Henry MP; Hartley, Louise; Eisinga, Anne; Main, Caroline; Roqué i Figuls, Marta; Bonfill Cosp, Xavier; Gabriel Sanchez, Rafael; Knight, Beatrice; Boardman, Henry MP (2015). "Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women". Reviews (3): CD002229. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub4. PMID 25754617.

- ↑ Darabi, M.; Rabbani, M.; Ani, M.; Zarean, E.; Panjehpour, M.; Movahedian, A. (2011). "Increased leukocyte ABCA1 gene expression in post-menopausal women on hormone replacement therapy". Gynecological Endocrinology. 27 (9): 701–705. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.507826. PMID 20807164.

- ↑ Young, Robert; Arlan F., Jr Fuller; Fuller, Arlan F.; Michael V. Seiden (2004). Uterine cancer. Hamilton, Ont: B.C. Decker. ISBN 1-55009-163-8.

- ↑ Copland, J. A.; Sheffield-Moore, M.; Koldzic-Zivanovic, N.; Gentry, S.; Lamprou, G.; Tzortzatou-Stathopoulou, F.; Zoumpourlis, V.; Urban, R. J.; Vlahopoulos, S. A. (2009). "Sex steroid receptors in skeletal differentiation and epithelial neoplasia: Is tissue-specific intervention possible?". BioEssays. 31 (6): 629–641. doi:10.1002/bies.200800138. PMID 19382224.

- ↑ Jeff Donn (2007-05-02). "Hormones may ward off dementia in women: Controversial treatment effective when taken soon after menopause". Associated Press.

- ↑ Schmidt R, Fazekas F, Reinhart B, Kapeller P, Fazekas G, Offenbacher H, Eber B, Schumacher M, Freidl W (November 1996). "Estrogen replacement therapy in older women: a neuropsychological and brain MRI study". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 44 (11): 1307–13. PMID 8909345.

- ↑ Voytko, ML; Murray, R; Higgs, GJ. (2009). "Executive Function and Attention Are Preserved in Older Surgically Menopausal Monkeys Receiving Estrogen or Estrogen Plus Progesterone". Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (33): 10362–10370. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1591-09.2009. PMC 2744632. PMID 19692611.

- ↑ Letendre, I.; Lopes, P. (2012). "Ménopause et risques carcinologiques". Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 41 (7): F33–F37. doi:10.1016/j.jgyn.2012.09.006. PMID 23062839.

- ↑ Stefanick ML; Anderson GL; Margolis KL; et al. (2006). "Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy". JAMA. 295 (14): 1647–57. doi:10.1001/jama.295.14.1647. PMID 16609086.

- ↑ Hulley SB, Grady D (2004). "The WHI estrogen-alone trial--do things look any better?". JAMA. 291 (14): 1769–71. doi:10.1001/jama.291.14.1769. PMID 15082705.

- ↑ "Association between hormone replacement therapy use and breast cancer risk varies by race/ethnicity, body mass index, and breast density". JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 105 (18). 2013. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt264. ISSN 0027-8874.

- In turn citing: Hou, N.; Hong, S.; Wang, W.; Olopade, O. I.; Dignam, J. J.; Huo, D. (2013). "Hormone Replacement Therapy and Breast Cancer: Heterogeneous Risks by Race, Weight, and Breast Density". JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 105 (18): 1365–1372. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt207. ISSN 0027-8874.

- ↑ Fournier, A. S.; Berrino, F.; Clavel-Chapelon, F. O. (2007). "Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 107 (1): 103–111. doi:10.1007/s10549-007-9523-x. PMC 2211383. PMID 17333341.

- ↑ Kuhl, H.; Schneider, H. P. G. (2013). "Progesterone – promoter or inhibitor of breast cancer". Climacteric. 16 Suppl 1: 54–68. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.768806. PMID 23336704.

- ↑ Management of the menopause after breast cancer Archived 2016-04-07 at Archive.is, from The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. College Statement C-Gyn 15. 1st Endorsed: February 2003. Current: November 2011. Review: November 2014

- ↑ Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer (12 February 2015). "Menopausal hormone use and ovarian cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of 52 epidemiological studies". The Lancet. 385 (9980): 1835. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61687-1.

- 1 2 Levine, M (2016). "Menopause accelerates biological aging". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113 (33): 9327–32. doi:10.1073/pnas.1604558113. PMC 4995944. PMID 27457926.

- ↑ Horvath S (2013). "DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types". Genome Biology. 14 (10): R115. doi:10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. PMC 4015143. PMID 24138928.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Fugh-Berman, Adriane (2015). "The Science of Marketing: How Pharmaceutical Companies Manipulated Medical Discourse on Menopause". Women's Reproductive Health. 2 (1): 18–23. doi:10.1080/23293691.2015.1039448. ISSN 2329-3691.

- ↑ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research on Cancer (2007). Combined Estrogen-progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-progestogen Menopausal Therapy. World Health Organization. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1.

- ↑ Mazzucco AE, Santoro E, DeSoto M, Lee JH (December 2010). "Hormone Therapy and Menopause". National Research Center for Women and Families.

- ↑ Gina Kolata (2007-04-19). "Sharp Drop in Rates of Breast Cancer Holds". New York Times.

- ↑ Roni Caryn Rabin (2007-08-28). "For a Low-Dose Hormone, Take Your Pick". New York Times.

Many women seeking natural remedies have turned to compounding pharmacies, which use bioidentical hormones that are chemically synthesized but with the same molecular structure as hormones produced by a woman's body.

- ↑ John Gever (2011-04-05). "New WHI Estrogen Analysis Shows Lower Breast Ca Risk". MedPageToday.

- 1 2 3 4 Singer, Natasha (4 August 2009). "Medical Papers by Ghostwriters Pushed Therapy". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fugh-Berman AJ (September 2010). "The haunting of medical journals: how ghostwriting sold "HRT"". PLoS Med. 7 (9): e1000335. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000335. PMC 2935455. PMID 20838656.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Steve Kent May; Steve May (20 January 2012). Case Studies in Organizational Communication: Ethical Perspectives and Practices: Ethical Perspectives and Practices. SAGE. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-1-4129-8309-9.

- 1 2 Miller VM, Harman SM (November 2017). "An update on hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: mini-review for the basic scientist". Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 313 (5): H1013–H1021. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00383.2017. PMID 28801526.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/26/business/26drug.html

- ↑ https://www.cnbc.com/id/33384753

- ↑ Tao M, Teng Y, Shao H, Wu P, Mills EJ (2011). "Knowledge, perceptions and information about hormone therapy (HT) among menopausal women: a systematic review and meta-synthesis". PLoS ONE. 6 (9): e24661. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024661. PMC 3174976. PMID 21949743.

External links