Estradiol (medication)

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛstrəˈdaɪoʊl/ ES-trə-DY-ohl[1][2] |

| Trade names | Numerous |

| Synonyms | Oestradiol; E2; 17β-Estradiol; Estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration |

• By mouth (tablet) • Sublingual (tablet) • Intranasal (nasal spray) • Transdermal (patch, gel, cream, emulsion, spray) • Vaginal (tablet, cream, insert (suppository), ring) • IM injection (oil solution) • SC injection (aq. soln.) • Subcutaneous implant |

| Drug class | Estrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability |

Oral: <5%[3] IM: 100%[4] |

| Protein binding |

~98%:[3][5] • Albumin: 60% • SHBG: 38% • Free: 2% |

| Metabolism | Liver (via hydroxylation, sulfation, glucuronidation) |

| Metabolites |

Major (90%):[3] • Estrone • Estrone sulfate • Estrone glucuronide • Estradiol glucuronide |

| Elimination half-life |

Oral: 13–20 hours[3] Sublingual: 8–18 hours[6] Transdermal (gel): 37 hours[7] IM (as EV): 4–5 days[4] IM (as EC): 8–10 days[8] IV (as E2): 1–2 hours[4] |

| Excretion |

Urine: 54%[3] Feces: 6%[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H24O2 |

| Molar mass | 272.388 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Estradiol, also spelled oestradiol, is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone.[9][10][11] It is an estrogen and is used mainly in menopausal hormone therapy and to treat low sex hormone levels in women.[9][12] It is also used in hormonal birth control for women, in hormone therapy for transgender women, and in the treatment of hormone-sensitive cancers like prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women, among other uses.[13][14][15][16][17] Estradiol can be taken by mouth, held and dissolved under the tongue, as a gel or patch that is applied to the skin, in through the vagina, by injection into muscle or fat, or through the use of an implant that is placed into fat, among other routes.[9]

Side effects of estradiol in women include breast tenderness, breast enlargement, headache, fluid retention, and nausea among others.[9][18] Men and children who are exposed to estradiol may develop symptoms of feminization, such as breast development and a feminine pattern of fat distribution, and men may also experience low testosterone levels and infertility.[19][20] It may increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer in women with intact uteruses if it is not taken together with a progestogen, for instance progesterone.[9] The combination of estradiol with a progestin, though not with progesterone, may increase the risk of breast cancer.[21][22] Estradiol should not be used in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding or who have breast cancer, among other contraindications.[18]

Estradiol is a naturally occurring and bioidentical estrogen, or an agonist of the estrogen receptor, the biological target of estrogens like endogenous estradiol.[9] Due to its estrogenic activity, estradiol has antigonadotropic effects and can inhibit fertility and suppress sex hormone production in both women and men.[23][24] Estradiol differs from non-bioidentical estrogens like conjugated estrogens and ethinylestradiol in various ways, with implications for tolerability and safety.[9]

Estradiol was first isolated in 1935.[25] It first became available as a medication in the form of estradiol benzoate, a prodrug of estradiol, in 1936.[26] Micronized estradiol, which allowed estradiol to be taken by mouth, was not introduced until 1975.[27] Estradiol is also used as other prodrugs like estradiol valerate and polyestradiol phosphate.[9] Related estrogens such as ethinylestradiol, which is the most common estrogen in birth control pills, and conjugated estrogens (brand name Premarin), which is used in menopausal hormone therapy, are used as medications as well.[9]

Medical uses

Hormone therapy

Menopause

Estradiol is used in menopausal hormone therapy to treat moderate to severe menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness and atrophy, and osteoporosis (bone loss).[9] As unopposed estrogen therapy increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer in women with intact uteruses, estradiol is usually combined with a progestogen like progesterone or medroxyprogesterone acetate to prevent the effects of estradiol on the endometrium.[9][28]

In terms of dosages of oral micronized estradiol used in menopausal hormone therapy, 0.5 mg/day is considered to be a very low dosage, 1 mg/day is a low dosage, 2 mg/day is a standard dosage, and 4 mg/day is a high dosage.[29][30] Similarly, 2 mg/day oral estradiol valerate is a standard dosage.[29] In the case of transdermal estradiol patches, 14 µg/day is a very low dosage, 25 µg/day is a low dosage, 50 µg/day is a standard dosage, and 100 µg/day is a high dosage.[29][30]

Hypogonadism

Estrogen is responsible for the mediation of puberty in females, and in girls with delayed puberty due to hypogonadism such as in Turner syndrome, estradiol is used to induce the development of and maintain female secondary sexual characteristics such as breasts, wide hips, and a female fat distribution.[31][12][32] It is also used to restore estradiol levels in adult premenopausal women with hypogonadism, for instance those with premature ovarian failure or who have undergone oophorectomy.[12][32] It is used to treat women with hypogonadism due to hypopituitarism as well.[32][12]

Transgender women

Estradiol is used as part of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women.[33][15] The drug is used in higher dosages prior to sex reassignment surgery or orchiectomy to help suppress testosterone levels; after this procedure, estradiol continues to be used at lower dosages to maintain estradiol levels in the normal premenopausal female range.[33][15]

Birth control

Although almost all combined oral contraceptives contain the synthetic estrogen ethinylestradiol,[34] natural estradiol itself is also used in some hormonal contraceptives, including in estradiol-containing oral contraceptives and combined injectable contraceptives.[13][14] It is formulated in combination with a progestin such as dienogest, nomegestrol acetate, or medroxyprogesterone acetate, and is often used in the form of an ester prodrug like estradiol valerate or estradiol cypionate.[13][14] Hormonal contraceptives contain a progestin and/or estrogen and prevent ovulation and thus the possibility of pregnancy by suppressing the secretion of the gonadotropins follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), the peak of which around the middle of the menstrual cycle causes ovulation to occur.[35]

Hormonal cancer

Prostate cancer

Estradiol is used as a form of high-dose estrogen therapy to treat prostate cancer and is similarly effective to other therapies such as androgen deprivation therapy with castration and antiandrogens.[16][11][36][37] It is used in the form of long-lasting injected estradiol prodrugs like polyestradiol phosphate, estradiol valerate, and estradiol undecylate,[11][36][38] and has also more recently been assessed in the form of transdermal estradiol patches.[36][39] Estrogens are effective in the treatment of prostate cancer by suppressing testosterone levels into the castrate range, increasing levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and thereby decreasing the fraction of free testosterone, and possibly also via direct cytotoxic effects on prostate cancer cells.[40][41][42] Parenteral estradiol is largely free of the cardiovascular side effects of the high oral dosages of synthetic estrogens like diethylstilbestrol ad ethinylestradiol that were used previously.[36][43][44] In addition, estrogens may have advantages relative to castration in terms of hot flashes, sexual interest and function, osteoporosis, cognitive function, and quality of life.[36][44][41][45] However, side effects such as gynecomastia and feminization in general may be difficult to tolerate and unacceptable for many men.[36]

Breast cancer

High-dose estrogen therapy is effective in the treatment of about 35% of cases of breast cancer in women who are at least 5 years menopausal and has comparable effectiveness to antiestrogen therapy with medications like the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) tamoxifen.[17][46][47] Although estrogens are rarely used in the treatment of breast cancer today and synthetic estrogens like diethylstilbestrol and ethinylestradiol have most commonly been used similarly to the case of prostate cancer, estradiol itself has been used in the treatment of breast cancer as well.[17][48] Polyestradiol phosphate is also used to treat breast cancer.[49][50]

Other uses

Infertility

Estrogens may be used in treatment of infertility in women when there is a need to develop sperm-friendly cervical mucous or an appropriate uterine lining.[51][52]

Lactation suppression

Estrogens can be used to suppress and cease lactation and breast engorgement in postpartum women who do not wish to breastfeed.[53][46] They do this by directly decreasing the sensitivity of the alveoli of the mammary glands to the lactogenic hormone prolactin.[46]

Tall stature

Estrogens have been used to limit final height in adolescent girls with tall stature.[54] They do this by inducing epiphyseal closure and suppressing growth hormone-induced hepatic production and by extension circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a hormone that causes the body to grow and increase in size.[54] Although ethinylestradiol and conjugated estrogens have mainly been used for this purpose, estradiol can also be employed.[55][56]

Breast enhancement

Estrogens are involved in breast development and estradiol may be used as a form of hormonal breast enhancement to increase the size of the breasts.[57][58][59] Both pseudopregnancy with a combination of high-dosage intramuscular estradiol valerate and hydroxyprogesterone caproate and polyestradiol phosphate monotherapy have been assessed for this purpose in clinical studies.[57][58][59] However, acute or temporary breast enlargement is a well-known side effect of estrogens, and increases in breast size tend to regress or disappear entirely following discontinuation of treatment.[57][59] Aside from in those without prior established breast development, evidence is lacking for long-term or sustained increases in breast size with estrogens.[57][59]

Schizophrenia

Estradiol has been found to be effective in the adjunctive treatment of schizophrenia in women.[60][61][62] It has been found to significantly reduce positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms, with particular benefits on positive symptoms.[60][61][62][63] Other estrogens, as well as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like raloxifene, have been found to be effective in the adjunctive treatment of schizophrenia in women similarly.[60][64][65] Estrogens may be useful in the treatment of schizophrenia in men as well, but their use in this population is limited by feminizing side effects.[66][67] SERMs, which have few or no feminizing side effects, have been found to be effective in the adjunctive treatment of schizophrenia in men similarly to in women and may be more useful than estrogens in this sex.[66][64][65]

Available forms

Estradiol is available in a variety of different formulations, including oral, intranasal, transdermal/topical, vaginal, injectable, and implantable preparations.[9][68] An ester may be attached to one or both of the hydroxyl groups of estradiol to improve its oral bioavailability and/or duration of action with injection.[9] Such modifications give rise to forms such as estradiol acetate (oral and vaginal), estradiol valerate (oral and injectable), estradiol cypionate (injectable), estradiol benzoate (injectable), estradiol undecylate (injectable), and polyestradiol phosphate (injectable; a polymerized ester of estradiol), which are all prodrugs of estradiol.[9][68][69]

| Route | Ingredient | Form | Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Estradiol | Micronized tablets | 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mg estradiol per tablet |

| Oral | Estradiol acetate | Tablets | 0.45, 0.9, or 1.8 mg estradiol acetate per tablet (discontinued) |

| Oral | Estradiol valerate | Tablets | 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mg estradiol valerate per tablet |

| Intranasal | Estradiol | Nasal sprays | 150 µg estradiol per spray (contains 60 sprays per bottle) (discontinued)[70][71] |

| Transdermal | Estradiol | Patches | 14, 25, 37.5, 50, 60, 75, or 100 µg estradiol per 24 hours for 3 to 4 or 7 days |

| Transdermal | Estradiol | Gel dispensers | 0.06% estradiol (0.87 or 1.25 g gel per activation -> 0.52 or 0.75 mg estradiol per activation) |

| Transdermal | Estradiol | Gel packets | 0.1% estradiol (0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 g gel per packet -> 2.5, 5, or 10 mg estradiol per packet) |

| Transdermal | Estradiol | Emulsions | 0.14% estradiol (1.74 g emulsion per pouch -> 4.35 mg estradiol per pouch; delivers 50 µg estradiol per day) |

| Transdermal | Estradiol | Sprays | 1.53 mg estradiol per spray |

| Vaginal | Estradiol | Tablets | 10 or 25 µg estradiol per tablet |

| Vaginal | Estradiol | Creams | 0.01% (0.1 mg estradiol per 1.0 g cream) |

| Vaginal | Estradiol | Inserts | 4 or 10 µg estradiol per insert (replaced daily for 2 weeks and then twice weekly) |

| Vaginal | Estradiol | Rings | 2 mg estradiol per ring (releases 7.5 µg estradiol per 24 hours for 3 months) |

| Vaginal | Estradiol acetate | Rings | 12.4 or 24.8 mg estradiol acetate per ring (release 50 or 100 µg estradiol per 24 hours for 3 months) |

| Intramusculara,b | Estradiol | Ampoules | 1.0 mg/mL estradiol |

| Intramusculara | Estradiol benzoate | Vials/ampoules | 0.2, 1, 2, 5, or 10 mg/mL; 50 mg/2 mL; 5 mg/100 mL estradiol benzoate |

| Intramusculara | Estradiol cypionate | Vials/ampoules | 1, 3, or 5 mg/mL estradiol cypionate |

| Intramusculara | Estradiol undecylate | Vials/ampoules | 100 mg/mL estradiol undecylate (discontinued) |

| Intramusculara | Estradiol valerate | Vials/ampoules | 5, 10, 20, or 40 mg/mL estradiol valerate |

| Intramusculara | Polyestradiol phosphate | Vials/ampoules | 40 or 80 mg polyestradiol phosphate per vial/ampoule |

| Subcutaneousc | Estradiol | Implants | 25, 50, or 100 mg estradiol per implant (usually replaced every 6 months)[72] |

| Footnotes: a = Injection. b = Encapsulated in microspheres. c = Surgical implantation. Notes: (1): This table does not include combination products, for instance estradiol formulated in combination with a progestin or androgen.[73][74] (2): Some of these formulations have been marketed previously but may no longer be available. (3): The availability of pharmaceutical estradiol products differs by country (see the Availability section of this article).[73] Sources: [74][75][76][77][78][79][80] | |||

Contraindications

Estradiol should be avoided when there is undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding, known, suspected or a history of breast cancer, current treatment for metastatic disease, known or suspected estrogen-dependent neoplasia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or history of these conditions, active or recent arterial thromboembolic disease such as stroke, myocardial infarction, liver dysfunction or disease. Estradiol should not be taken by people with a hypersensitivity/allergy or those who are pregnant or are suspected pregnant.[18]

Side effects

Common side effects of estradiol in women include headache, breast pain or tenderness, breast enlargement, irregular vaginal bleeding or spotting, abdominal cramps, bloating, fluid retention, and nausea.[18][81][3] Other possible side effects of estrogens may include high blood pressure, high blood sugar, enlargement of uterine fibroids, melasma, vaginal yeast infections, and liver problems.[18] In men, estrogens can cause breast pain or tenderness, gynecomastia (male breast development), feminization, demasculinization, sexual dysfunction (decreased libido and erectile dysfunction), hypogonadism, testicular atrophy, and infertility.[19][20]

Long-term effects

Uncommon but serious possible side effects of estrogens associated with long-term therapy may include breast cancer, uterine cancer, stroke, heart attack, blood clots, dementia, gallbladder disease, and ovarian cancer.[27] Warning signs of these serious side effects include breast lumps, unusual vaginal bleeding, dizziness, faintness, changes in speech, severe headaches, chest pain, shortness of breath, pain in the legs, changes in vision, and vomiting.[27]

Due to health risks observed with the combination of conjugated estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) studies (see below), the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) label for Estrace (estradiol) advises that estrogens should be used in menopausal hormone therapy only for the shortest time possible and at the lowest effective dose.[18] While the FDA states that is unknown if these risks generalize to estradiol (alone or in combination with progesterone or a progestin), it advises that in the absence of comparable data, the risks should be assumed to be similar.[18] When used to treat menopausal symptoms, the FDA recommends that discontinuation of estradiol should be attempted every three to six months via a gradual dose taper.[18]

Despite the recommendations of the FDA however, it appears that the combination of bioidentical transdermal or vaginal estradiol and oral or vaginal progesterone is a safer form of hormone therapy than oral conjugated estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate and may not have the same health risks.[82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90] Advantages may include reduced or no risk of venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer, among others.[82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90]

| Event | Relative Risk CEEs/MPA vs. placebo at 5.2 years (95% CI*) | Placebo (n = 8102) | CEEs/MPA (n = 8506) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Risk per 10,000 Women-Years | |||||||||

| Coronary heart disease events Non-fatal myocardial infarction Coronary heart disease death | 1.29 (1.02–1.63) 1.32 (1.02–1.72) 1.18 (0.70–1.97) | 30 23 6 | 37 30 7 | ||||||

| Invasive breast cancera | 1.26 (1.00–1.59) | 30 | 38 | ||||||

| Stroke | 1.41 (1.07–1.85) | 21 | 29 | ||||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 2.13 (1.39–3.25) | 8 | 16 | ||||||

| Colorectal cancer | 0.63 (0.43–0.92) | 16 | 10 | ||||||

| Endometrial cancer | 0.83 (0.47–1.47) | 6 | 5 | ||||||

| Hip fracture | 0.66 (0.45–0.98) | 15 | 10 | ||||||

| Death due to causes other than above | 0.92 (0.74–1.14) | 40 | 37 | ||||||

| Global Indexb | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) | 151 | 170 | ||||||

| Deep vein thrombosisc | 2.07 (1.49–2.87) | 13 | 26 | ||||||

| Vertebral fracturesc | 0.66 (0.44–0.98) | 15 | 9 | ||||||

| Other osteoporotic fracturesc | 0.77 (0.69–0.86) | 170 | 131 | ||||||

| WHI = Women's Health Initiative. CEEs = Conjugated estrogens. MPA = Medroxyprogesterone acetate. a = Includes metastatic and non-metastatic breast cancer with the exception of in situ breast cancer. b = A subset of the events was combined in a "global index", defined as the earliest occurrence of coronary heart disease events, invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, hip fracture, or death due to other causes. c = Not included in Global Index. * = Nominal confidence intervals unadjusted for multiple looks and multiple comparisons. Sources:[18][91] | |||||||||

Overdose

Serious adverse effects have not been described following acute overdose of large doses of estrogen-containing birth control pills by small children.[69] Overdose of estrogens has been associated with nausea, vomiting, and withdrawal bleeding.[69] During pregnancy, levels of estradiol increase to very high concentrations that are as much as 100-fold normal levels.[77][92][93] In late pregnancy, the body produces and secretes approximately 100 mg in estrogens per day.[77]

Interactions

Inducers of cytochrome P450 enzymes like CYP3A4 such as St. John's wort, phenobarbital, carbamazepine and rifampicin decrease the circulating levels of estradiol by accelerating its metabolism, whereas inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes like CYP3A4 such as erythromycin, cimetidine,[94] clarithromycin, ketoconazole, itraconazole, ritonavir and grapefruit juice may slow its metabolism resulting in increased levels of estradiol in the circulation.[18] There is an interaction between estradiol and alcohol such that alcohol considerably increases circulating levels of estradiol during oral estradiol therapy and also increases estradiol levels in normal premenopausal women and with parenteral estradiol therapy.[95][11][96][97] This appears to be due to a decrease in hepatic 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (17β-HSD2) activity and hence estradiol inactivation into estrone due to an alcohol-mediated increase in the ratio of NADH to NAD in the liver.[96][97] Spironolactone can reduce the bioavailability of oral estradiol.[98]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Estradiol is an estrogen, or an agonist of the estrogen receptors (ERs), the ERα and ERβ.[9] It is also an agonist of membrane estrogen receptors (mERs), including the GPER, Gq-mER, ER-X, and ERx.[99][100] Estradiol is highly selective for these ERs and mERs, and does not interact importantly with other steroid hormone receptors.[101][102][103] It is far more potent as an estrogen than are other bioidentical estrogens like estrone and estriol.[9]

The ERs are expressed widely throughout the body, including in the breasts, uterus, vagina, fat, skin, bone, liver, pituitary gland, hypothalamus, and other parts of the brain.[25] In accordance, estradiol has numerous effects throughout the body.[25][104][105][106][107][108][109][11][40][110][111][75][112] Among other effects, estradiol produces breast development, feminization, changes in the female reproductive system, changes in liver protein synthesis, and changes in brain function.[108][109][11][40][110][111][75][112] The effects of estradiol can influence health in both positive and negative ways.[9] In addition to the aforementioned effects, estradiol has antigonadotropic effects due to its estrogenic activity, and can inhibit ovulation and suppress gonadal sex hormone production.[109][11][40][41][42][23][24] At sufficiently high dosages, estradiol is a powerful antigonadotropic, capable of suppressing testosterone levels into the castrate/female range in men.[40][41][42][23][24]

There are differences between estradiol and other estrogens, such as non-bioidentical estrogens like natural conjugated estrogens and synthetic estrogens like ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol, with implications for pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics as well as efficacy, tolerability, and safety.[9]

Pharmacokinetics

Estradiol can be taken by a variety of different routes of administration.[9] These include oral, buccal, sublingual, intranasal, transdermal (gels, creams, patches), vaginal (tablets, creams, rings, suppositories), rectal, by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection (in oil or aqueous), and as a subcutaneous implant.[9] The pharmacokinetics of estradiol, including its bioavailability, metabolism, biological half-life, and other parameters, differ by route of administration.[9] Likewise, the potency of estradiol, and its local effects in certain tissues, most importantly the liver, differ by route of administration as well.[9] In particular, the oral route is subject to a high first-pass effect, which results in high levels of estradiol and consequent estrogenic effects in the liver and low potency due to first-pass hepatic and intestinal metabolism into metabolites like estrone and estrogen conjugates.[9] Conversely, this is not the case for parenteral (non-oral) routes, which bypass the intestines and liver.[9]

Different estradiol routes and dosages can achieve widely varying circulating estradiol levels.[9] For purposes of comparison with normal physiological circumstances, menstrual cycle circulating levels of estradiol in premenopausal women are 40 pg/mL in the early follicular phase, 250 pg/mL at the middle of the cycle, and 100 pg/mL during the mid-luteal phase.[75] Mean integrated levels of circulating estradiol in premenopausal women across the whole menstrual cycle have been reported to be in the range of 80 and 150 pg/mL, according to some sources.[113][114][115]

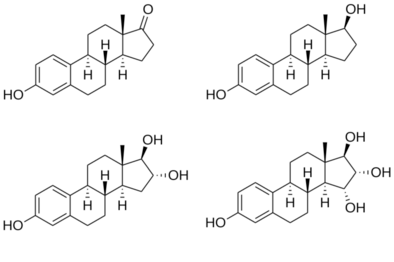

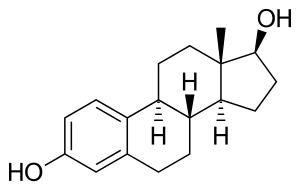

Chemistry

Estradiol is a naturally occurring estrane steroid.[9][116] It is also known as 17β-estradiol (to distinguish it from 17α-estradiol) or as estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol.[117][118][9] It has two hydroxyl groups, one at the C3 position and the other at the C17β position, as well as three double bonds in the A ring (the estra-1,3,5(10)-triene core).[116][119] Due to its two hydroxyl groups, estradiol is often abbreviated as E2.[116] The structurally related estrogens, estrone (E1), estriol (E3), and estetrol (E4) have one, three, and four hydroxyl groups, respectively.[116][120]

Hemihydrate

A hemihydrate form of estradiol, estradiol hemihydrate, is widely used medically under a large number of brand names similarly to estradiol.[118] In terms of activity and bioequivalence, estradiol and its hemihydrate are identical, with the only disparities being an approximate 1% difference in potency by weight (due to the presence of water molecules in the hemihydrate form of the substance) and a slower rate of release with certain formulations of the hemihydrate.[121][122] This is because estradiol hemihydrate is more hydrated than anhydrous estradiol, and for this reason, is more insoluble in water in comparison, which results in slower absorption rates with specific formulations of the drug such as vaginal tablets.[122] Estradiol hemihydrate has also been shown to result in less systemic absorption as a vaginal tablet formulation relative to other topical estradiol formulations such as vaginal creams.[123] Estradiol hemihydrate is used in place of estradiol in some estradiol products.[74][124][125]

Derivatives

A variety of C17β and/or C3 ester prodrugs of estradiol, such as estradiol acetate, estradiol benzoate, estradiol cypionate, estradiol dipropionate, estradiol enantate, estradiol undecylate, estradiol valerate, and polyestradiol phosphate (an estradiol ester in polymeric form), among many others, have been developed and introduced for medical use as estrogens.[117][118][9][126] Estramustine phosphate is also an estradiol ester, but with a nitrogen mustard moiety attached, and is used as an alkylating antineoplastic agent in the treatment of prostate cancer.[117][118][127] Cloxestradiol acetate and promestriene are ether prodrugs of estradiol that have been introduced for medical use as estrogens as well, although they are little known and rarely used.[117][118]

Synthetic derivatives of estradiol used as estrogens include ethinylestradiol, ethinylestradiol sulfonate, mestranol, methylestradiol, moxestrol, and quinestrol, all of which are 17α-substituted estradiol derivatives.[117][118][9] Synthetic derivatives of estradiol used in scientific research include 8β-VE2 and 16α-LE2.[128]

History

Estradiol was first isolated in 1935.[25] It was also originally known as dihydroxyestrin or alpha-estradiol.[119][129] It was first marketed, as estradiol benzoate, in 1936.[26] Estradiol was also marketed in the 1930s under brand names such as Progynon-DH, Ovocylin, and Dimenformon.[119][129] Micronized estradiol, via the oral route, was first evaluated in 1972,[130] and this was followed by the evaluation of vaginal and intranasal micronized estradiol in 1977.[131] Oral micronized estradiol was first approved in the United States under the brand name Estrace in 1975.[27] In 1931, Butenandt found that the benzoic acid ester of estrone had a prolonged duration of action.[53][132] Subsequently, Schwenk and Hildebrant synthesized estradiol benzoate from estradiol in 1933,[133][134] and estradiol benzoate was introduced by Schering-Kahlbaum for medical use via intramuscular injection under the brand name Progynon-B in 1936.[26] It was the first estrogen ester to be marketed,[135] and has since been followed by many additional esters, for instance estradiol valerate and estradiol cypionate in the 1950s.[118][117][136] Ethinylestradiol was synthesized from estradiol by Inhoffen and Hohlweg in 1938 and was introduced for oral use by Schering in the United States under the brand name Estinyl in 1943.[133][137] It remains widely used in combined oral contraceptives.[133]

Society and culture

Generic names

Estradiol is the generic name of estradiol in American English and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCF, and JAN.[73][118][117][138][139] Estradiolo is the name of estradiol in Italian and the DCIT[73] and estradiolum is its name in Latin, whereas its name remains unchanged as estradiol in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and German.[73][118] Oestradiol was the former BAN of estradiol and its name in British English,[138] but the spelling was eventually changed to estradiol.[73] When estradiol is provided in its hemihydrate form, its INN is estradiol hemihydrate.[118]

Brand names

Estradiol is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[118][73] Examples of major brand names in which estradiol has been marketed in include Climara, Climen, Dermestril, Divigel, Estrace, Natifa, Estraderm, Estraderm TTS, Estradot, Estreva, Estrimax, Estring, Estrofem, EstroGel, Evorel, Fem7 (or FemSeven), Imvexxy, Menorest, Oesclim, OestroGel, Sandrena, Systen, and Vagifem.[118][73] Estradiol valerate is marketed mainly as Progynova and Progynon-Depot, while it is marketed as Delestrogen in the U.S.[118][74] Estradiol cypionate is used mainly in the U.S. and is marketed under the brand name Depo-Estradiol.[118][74] Estradiol acetate is available as Femtrace, Femring, and Menoring.[74]

Estradiol is also widely available in combination with progestogens.[73] It is available in combination with norethisterone acetate under the major brand names Activelle, Cliane, Estalis, Eviana, Evorel Conti, Evorel Sequi, Kliogest, Novofem, Sequidot, and Trisequens; with drospirenone as Angeliq; with dydrogesterone as Femoston, Femoston Conti; and with nomegestrol acetate as Zoely.[73] Estradiol valerate is available with cyproterone acetate as Climen; with dienogest as Climodien and Qlaira; with norgestrel as Cyclo-Progynova and Progyluton; with levonorgestrel as Klimonorm; with medroxyprogesterone acetate as Divina and Indivina; and with norethisterone enantate as Mesigyna and Mesygest.[73] Estradiol cypionate is available with medroxyprogesterone acetate as Cyclo-Provera, Cyclofem, Feminena, Lunelle, and Novafem;[14] estradiol enantate with algestone acetophenide as Deladroxate and Topasel;[73][140][141] and estradiol benzoate is marketed with progesterone as Mestrolar and Nomestrol.[73]

Estradiol valerate is also widely available in combination with prasterone enantate (DHEA enantate) under the brand name Gynodian Depot.[73]

Availability

Estradiol and/or its esters are widely available in countries throughout the world in a variety of formulations.[73][142][143][118][74]

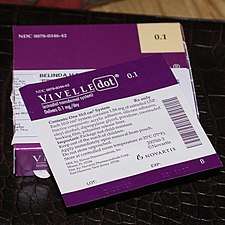

United States

As of November 2016, estradiol is available in the United States in the following forms:[74]

- Oral tablets (Femtrace (as estradiol acetate), Gynodiol, Innofem, generics)

- Transdermal patches (Alora, Climara, Esclim, Estraderm, FemPatch, Menostar, Minivelle, Vivelle, Vivelle-Dot, generics)

- Topical gels (Divigel, Elestrin, EstroGel), emulsions (Estrasorb), and sprays (Evamist)

- Vaginal tablets (Vagifem, generics), creams (Estrace), inserts (Imvexxy), and rings (Estring, Femring (as estradiol acetate))

- Oil solution for intramuscular injection (Delestrogen (as estradiol valerate), Depo-Estradiol (as estradiol cypionate))

Oral estradiol valerate (Progynova) and other esters of estradiol that are used by injection like estradiol benzoate, estradiol enantate, and estradiol undecylate all are not marketed in the U.S.[74] Polyestradiol phosphate (Estradurin) was marketed in the U.S. previously but is no longer available.[74]

Estradiol is also available in the U.S. in combination with progestogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and as a combined hormonal contraceptive:[74]

- Oral tablets with drospirenone (Angeliq) and norethisterone acetate (Activella, Amabelz) and as estradiol valerate with dienogest (Natazia)

- Transdermal patches with levonorgestrel (Climara Pro) and norethisterone acetate (Combipatch)

A combination formulation of estradiol and progesterone micronized in oil-filled oral capsules (TX-001HR) is currently under development in the U.S. for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and endometrial hyperplasia but has not yet completed development and been approved.[144][145]

Estradiol and estradiol esters are also available in custom preparations from compounding pharmacies in the U.S.[146] This includes subcutaneous pellet implants, which are not available in the United States as FDA-approved pharmaceutical drugs.[147] In addition, topical creams that contain estradiol are generally regulated as cosmetics rather than as drugs in the U.S. and hence are also sold over-the-counter and may be purchased without a prescription on the Internet.[148]

References

- ↑ Susan M. Ford; Sally S. Roach (7 October 2013). Roach's Introductory Clinical Pharmacology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 525–. ISBN 978-1-4698-3214-2.

- ↑ Maryanne Hochadel; Mosby (1 April 2015). Mosby's Drug Reference for Health Professions. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 602–. ISBN 978-0-323-31103-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stanczyk, Frank Z.; Archer, David F.; Bhavnani, Bhagu R. (2013). "Ethinyl estradiol and 17β-estradiol in combined oral contraceptives: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and risk assessment". Contraception. 87 (6): 706–727. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.12.011. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 23375353.

- 1 2 3 Düsterberg B, Nishino Y (1982). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacological features of oestradiol valerate". Maturitas. 4 (4): 315–24. PMID 7169965.

- ↑ Tommaso Falcone; William W. Hurd (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 22, 362, 388. ISBN 0-323-03309-1.

- ↑ Price, T; Blauer, K; Hansen, M; Stanczyk, F; Lobo, R; Bates, G (1997). "Single-dose pharmacokinetics of sublingual versus oral administration of micronized 17-estradiol". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 89 (3): 340–345. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00513-3. ISSN 0029-7844.

- ↑ Naunton, Mark; Al Hadithy, Asmar F. Y.; Brouwers, Jacobus R. B. J.; Archer, David F. (2006). "Estradiol gel". Menopause. 13 (3): 517–527. doi:10.1097/01.gme.0000191881.52175.8c. ISSN 1072-3714.

- ↑ Sierra-Ramírez JA, Lara-Ricalde R, Lujan M, Velázquez-Ramírez N, Godínez-Victoria M, Hernádez-Munguía IA, et al. (2011). "Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics after subcutaneous and intramuscular administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate (25 mg) and estradiol cypionate (5 mg)". Contraception. 84 (6): 565–70. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.014. PMID 22078184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- ↑ Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens I: Physiology and Mechanisms of Action of Estrogens and Antiestrogens. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 121, 226, 235–237. ISBN 978-3-642-58616-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 163–178, 235–237, 252–253, 261–276, 538–543. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Christin-Maitre S (2017). "Use of Hormone Replacement in Females with Endocrine Disorders". Horm Res Paediatr. 87 (4): 215–223. doi:10.1159/000457125. PMID 28376481.

- 1 2 3 Christin-Maitre S, Laroche E, Bricaire L (January 2013). "A new contraceptive pill containing 17β-estradiol and nomegestrol acetate". Womens Health (Lond). 9 (1): 13–23. doi:10.2217/whe.12.70. PMID 23241152.

- 1 2 3 4 Newton JR, D'arcangues C, Hall PE (1994). "A review of "once-a-month" combined injectable contraceptives". J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 4 Suppl 1: S1–34. doi:10.3109/01443619409027641. PMID 12290848.

- 1 2 3 Wesp LM, Deutsch MB (2017). "Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 40 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. PMID 28159148.

- 1 2 Ali Shah SI (2015). "Emerging potential of parenteral estrogen as androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer". South Asian J Cancer. 4 (2): 95–7. doi:10.4103/2278-330X.155699. PMC 4418092. PMID 25992351.

- 1 2 3 Coelingh Bennink HJ, Verhoeven C, Dutman AE, Thijssen J (January 2017). "The use of high-dose estrogens for the treatment of breast cancer". Maturitas. 95: 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.10.010. PMID 27889048.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Warner Chilcott (March 2005). "ESTRACE TABLETS, (estradiol tablets, USP)" (PDF). fda.gov. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- 1 2 Richard P. Pohanish (2011). Sittig's Handbook of Toxic and Hazardous Chemicals and Carcinogens. William Andrew. pp. 1167–. ISBN 978-1-4377-7869-4.

- 1 2 Russell La Fayette Cecil; J. Claude Bennett; Fred Plum (1996). Cecil Textbook of Medicine. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-3575-0.

Estrogen excess in men causes inhibition of gonadotropin secretion and secondary hypogonadism. Estrogen excess may result from either exogenous administration of estrogens or estrogenic substances (e.g., diethylstilbestrol administration [...]

- ↑ Yang Z, Hu Y, Zhang J, Xu L, Zeng R, Kang D (February 2017). "Estradiol therapy and breast cancer risk in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 33 (2): 87–92. doi:10.1080/09513590.2016.1248932. PMID 27898258.

- ↑ Lambrinoudaki I (April 2014). "Progestogens in postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer". Maturitas. 77 (4): 311–7. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.01.001. PMID 24485796.

- 1 2 3 Stege R, Carlström K, Collste L, Eriksson A, Henriksson P, Pousette A (1988). "Single drug polyestradiol phosphate therapy in prostatic cancer". Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 11 Suppl 2: S101–3. doi:10.1097/00000421-198801102-00024. PMID 3242384.

- 1 2 3 Ockrim JL, Lalani EN, Laniado ME, Carter SS, Abel PD (2003). "Transdermal estradiol therapy for advanced prostate cancer--forward to the past?". J. Urol. 169 (5): 1735–7. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000061024.75334.40. PMID 12686820.

- 1 2 3 4 Fritz F. Parl (2000). Estrogens, Estrogen Receptor and Breast Cancer. IOS Press. pp. 4, 111. ISBN 978-0-9673355-4-4.

- 1 2 3 Enrique Raviña; Hugo Kubinyi (16 May 2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. p. 175. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Set_Current_Drug&ApplNo=084499&DrugName=ESTRACE&ActiveIngred=ESTRADIOL&SponsorApplicant=BRISTOL%20MYERS%20SQUIBB&ProductMktStatus=3&goto=Search.DrugDetails

- ↑ Mutschler, Ernst; Schäfer-Korting, Monika (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 434, 444. ISBN 3-8047-1763-2.

- 1 2 3 Laura Marie Borgelt (2010). Women's Health Across the Lifespan: A Pharmacotherapeutic Approach. ASHP. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-1-58528-194-7.

- 1 2 Joseph T. DiPiro; Robert L. Talbert; Gary C. Yee; Gary R. Matzke; Barbara G. Wells; L. Michael Posey (25 April 2011). Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, Eighth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 1425. ISBN 978-0-07-178499-3.

- ↑ Matthews D, Bath L, Högler W, Mason A, Smyth A, Skae M (October 2017). "Hormone supplementation for pubertal induction in girls". Arch. Dis. Child. 102 (10): 975–980. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-311372. PMID 28446424.

- 1 2 3 Laura Rosenthal; Jacqueline Burchum (17 February 2017). Lehne's Pharmacotherapeutics for Advanced Practice Providers - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 524–. ISBN 978-0-323-44779-9.

- 1 2 World Professional Association for Transgender Health (September 2011), Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Seventh Version (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016

- ↑ Evans G, Sutton EL (May 2015). "Oral contraception". Med Clin North Am. 99 (3): 479–503. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.004. PMID 25841596.

- ↑ Glasier, Anna (2010). "Contraception". In Jameson, J. Larry; De Groot, Leslie J. Endocrinology (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 2417–2427. ISBN 978-1-4160-5583-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lycette JL, Bland LB, Garzotto M, Beer TM (2006). "Parenteral estrogens for prostate cancer: can a new route of administration overcome old toxicities?". Clin Genitourin Cancer. 5 (3): 198–205. doi:10.3816/CGC.2006.n.037. PMID 17239273.

- ↑ Cox RL, Crawford ED (1995). "Estrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer". J. Urol. 154 (6): 1991–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66670-9. PMID 7500443.

- ↑ Altwein, J. (1983). "Controversial Aspects of Hormone Manipulation in Prostatic Carcinoma": 305–316. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-4349-3_38.

- ↑ Ockrim JL; Lalani el-N; Kakkar AK; Abel PD (August 2005). "Transdermal estradiol therapy for prostate cancer reduces thrombophilic activation and protects against thromboembolism". J. Urol. 174 (2): 527–33, discussion 532–3. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000165567.99142.1f. PMID 16006886.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Waun Ki Hong; James F. Holland (2010). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine 8. PMPH-USA. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Scherr DS, Pitts WR (2003). "The nonsteroidal effects of diethylstilbestrol: the rationale for androgen deprivation therapy without estrogen deprivation in the treatment of prostate cancer". J. Urol. 170 (5): 1703–8. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000077558.48257.3d. PMID 14532759.

- 1 2 3 Coss, Christopher C.; Jones, Amanda; Parke, Deanna N.; Narayanan, Ramesh; Barrett, Christina M.; Kearbey, Jeffrey D.; Veverka, Karen A.; Miller, Duane D.; Morton, Ronald A.; Steiner, Mitchell S.; Dalton, James T. (2012). "Preclinical Characterization of a Novel Diphenyl Benzamide Selective ERα Agonist for Hormone Therapy in Prostate Cancer". Endocrinology. 153 (3): 1070–1081. doi:10.1210/en.2011-1608. ISSN 0013-7227. PMID 22294742.

- ↑ von Schoultz B, Carlström K, Collste L, Eriksson A, Henriksson P, Pousette A, Stege R (1989). "Estrogen therapy and liver function--metabolic effects of oral and parenteral administration". Prostate. 14 (4): 389–95. PMID 2664738.

- 1 2 Ockrim J, Lalani EN, Abel P (2006). "Therapy Insight: parenteral estrogen treatment for prostate cancer--a new dawn for an old therapy". Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 3 (10): 552–63. doi:10.1038/ncponc0602. PMID 17019433.

- ↑ Wibowo E, Schellhammer P, Wassersug RJ (2011). "Role of estrogen in normal male function: clinical implications for patients with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy". J. Urol. 185 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.094. PMID 21074215.

- 1 2 3 John A. Thomas; Edward J. Keenan (6 December 2012). Principles of Endocrine Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-1-4684-5036-1.

- ↑ William R. Miller; James N. Ingle (8 March 2002). Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. CRC Press. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-0-203-90983-6.

- ↑ Ellis, MJ; Dehdahti, F; Kommareddy, A; Jamalabadi-Majidi, S; Crowder, R; Jeffe, DB; Gao, F; Fleming, G; Silverman, P; Dickler, M; Carey, L; Marcom, PK (2014). "A randomized phase 2 trial of low dose (6 mg daily) versus high dose (30 mg daily) estradiol for patients with estrogen receptor positive aromatase inhibitor resistant advanced breast cancer". Cancer Research. 69 (2 Supplement): 16. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS-16. ISSN 0008-5472.

- ↑ http://pharmanovia.com/product/estradurin/

- ↑ Ostrowski MJ, Jackson AW (1979). "Polyestradiol phosphate: a preliminary evaluation of its effect on breast carcinoma". Cancer Treat Rep. 63 (11–12): 1803–7. PMID 393380.

- ↑ J. Aiman (6 December 2012). Infertility: Diagnosis and Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-1-4613-8265-2.

- ↑ Glenn L. Schattman; Sandro Esteves; Ashok Agarwal (12 May 2015). Unexplained Infertility: Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Treatment. Springer. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-1-4939-2140-9.

- 1 2 A. Labhart (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 512, 696. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- 1 2 Juul A (2001). "The effects of oestrogens on linear bone growth". Hum. Reprod. Update. 7 (3): 303–13. PMID 11392377.

- ↑ Albuquerque EV, Scalco RC, Jorge AA (2017). "Management of Endocrine Disease: Diagnostic and therapeutic approach of tall stature". Eur. J. Endocrinol. doi:10.1530/EJE-16-1054. PMID 28274950.

- ↑ Upners EN, Juul A (2016). "Evaluation and phenotypic characteristics of 293 Danish girls with tall stature: effects of oral administration of natural 17β-estradiol". Pediatr. Res. 80 (5): 693–701. doi:10.1038/pr.2016.128. PMID 27410906.

- 1 2 3 4 Gunther Göretzlehner; Christian Lauritzen; Thomas Römer; Winfried Rossmanith (1 January 2012). Praktische Hormontherapie in der Gynäkologie. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 385–. ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4.

- 1 2 R.E. Mansel; Oystein Fodstad; Wen G. Jiang (14 June 2007). Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 217–. ISBN 978-1-4020-5866-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Hartmann BW, Laml T, Kirchengast S, Albrecht AE, Huber JC (1998). "Hormonal breast augmentation: prognostic relevance of insulin-like growth factor-I". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 12 (2): 123–7. doi:10.3109/09513599809024960. PMID 9610425.

- 1 2 3 Begemann MJ, Dekker CF, van Lunenburg M, Sommer IE (November 2012). "Estrogen augmentation in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of current evidence". Schizophr. Res. 141 (2–3): 179–84. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.016. PMID 22998932.

- 1 2 Kulkarni J, Gavrilidis E, Wang W, Worsley R, Fitzgerald PB, Gurvich C, Van Rheenen T, Berk M, Burger H (June 2015). "Estradiol for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a large-scale randomized-controlled trial in women of child-bearing age". Mol. Psychiatry. 20 (6): 695–702. doi:10.1038/mp.2014.33. PMID 24732671.

- 1 2 Brzezinski A, Brzezinski-Sinai NA, Seeman MV (May 2017). "Treating schizophrenia during menopause". Menopause. 24 (5): 582–588. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000772.

- ↑ McGregor C, Riordan A, Thornton J (October 2017). "Estrogens and the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia: Possible neuroprotective mechanisms". Front Neuroendocrinol. 47: 19–33. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2017.06.003. PMID 28673758.

- 1 2 de Boer J, Prikken M, Lei WU, Begemann M, Sommer I (January 2018). "The effect of raloxifene augmentation in men and women with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". NPJ Schizophr. 4 (1): 1. doi:10.1038/s41537-017-0043-3. PMC 5762671. PMID 29321530.

- 1 2 Khan MM (July 2016). "Neurocognitive, Neuroprotective, and Cardiometabolic Effects of Raloxifene: Potential for Improving Therapeutic Outcomes in Schizophrenia". CNS Drugs. 30 (7): 589–601. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0343-6. PMID 27193386.

- 1 2 Kulkarni J, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R, Van Rheenen T, Hayes E (2013). "The role of estrogen in the treatment of men with schizophrenia". Int J Endocrinol Metab. 11 (3): 129–36. doi:10.5812/ijem.6615. PMC 3860106. PMID 24348584.

- ↑ Owens SJ, Murphy CE, Purves-Tyson TD, Weickert TW, Shannon Weickert C (February 2018). "Considering the role of adolescent sex steroids in schizophrenia". J. Neuroendocrinol. 30 (2). doi:10.1111/jne.12538. PMID 28941299.

- 1 2 Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1419–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- 1 2 3 Mikkola A, Ruutu M, Aro J, Rannikko S, Salo J (1999). "The role of parenteral polyestradiol phosphate in the treatment of advanced prostatic cancer on the threshold of the new millennium". Ann Chir Gynaecol. 88 (1): 18–21. PMID 10230677.

- ↑ http://www.medicines.org.au/files/secaerod.pdf

- ↑ Sahin FK, Koken G, Cosar E, Arioz DT, Degirmenci B, Albayrak R, Acar M (2008). "Effect of Aerodiol administration on ocular arteries in postmenopausal women". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 24 (4): 173–7. doi:10.1080/09513590701807431. PMID 18382901.

300 μg 17β-estradiol (Aerodiol®; Servier, Chambrayles-Tours, France) was administered via the nasal route by a gynecologist. This product is unavailable after March 31, 2007 because its manufacturing and marketing are being discontinued.

- ↑ Leo Jr. Plouffe; Veronica A. Ravnikar; Leon Speroff; Nelson B. Watts (6 December 2012). Comprehensive Management of Menopause. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 271–. ISBN 978-1-4612-4330-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 https://www.drugs.com/international/estradiol.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogerio A. Lobo (5 June 2007). Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Academic Press. pp. 177, 217–226, 770–771. ISBN 978-0-08-055309-2.

- ↑ Tommaso Falcone; William W. Hurd (14 June 2017). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery: A Practical Guide. Springer. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-3-319-52210-4.

- 1 2 3 Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 889, 1059–1060, 2153. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- ↑ A. Kleemann; J. Engel; B. Kutscher; D. Reichert (14 May 2014). Pharmaceutical Substances, 5th Edition, 2009: Syntheses, Patents and Applications of the most relevant APIs. Thieme. pp. 1167–1174. ISBN 978-3-13-179525-0.

- ↑ Muller (19 June 1998). European Drug Index: European Drug Registrations, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. pp. 276, 454–455, 566–567. ISBN 978-3-7692-2114-5.

- ↑ Krishna; Usha R. And Shah (1996). Menopause. Orient Blackswan. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-81-250-0910-8.

- ↑ Pfizer (August 2008). "ESTRING (estradiol vaginal ring)" (PDF).

- 1 2 L'hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, Genazzani AR (2008). "Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review". Maturitas. 60 (3–4): 185–201. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.07.007. PMID 18775609.

- 1 2 Holtorf K (January 2009). "The bioidentical hormone debate: are bioidentical hormones (estradiol, estriol, and progesterone) safer or more efficacious than commonly used synthetic versions in hormone replacement therapy?". Postgrad Med. 121 (1): 73–85. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.01.1949. PMID 19179815.

- 1 2 Conaway E (March 2011). "Bioidentical hormones: an evidence-based review for primary care providers". J Am Osteopath Assoc. 111 (3): 153–64. PMID 21464264.

- 1 2 Simon JA (April 2012). "What's new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone". Climacteric. 15 Suppl 1: 3–10. doi:10.3109/13697137.2012.669332. PMID 22432810.

- 1 2 Mueck AO (April 2012). "Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone". Climacteric. 15 Suppl 1: 11–7. doi:10.3109/13697137.2012.669624. PMID 22432811.

- 1 2 L'Hermite M (August 2013). "HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT". Climacteric. 16 Suppl 1: 44–53. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.808563. PMID 23848491.

- 1 2 Simon JA (July 2014). "What if the Women's Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead?". Menopause. 21 (7): 769–83. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000169. PMID 24398406.

- 1 2 L'Hermite M (August 2017). "Bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy: registered hormones (non-oral estradiol ± progesterone) are optimal". Climacteric. 20 (4): 331–338. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1291607. PMID 28301216.

- 1 2 Davey DA (March 2018). "Menopausal hormone therapy: a better and safer future". Climacteric: 1–8. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1439915. PMID 29526116.

- ↑ Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J (July 2002). "Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 288 (3): 321–33. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321. PMID 12117397.

- ↑ http://www.ilexmedical.com/files/PDF/Estradiol_ARC.pdf

- ↑ Roger Smith (Prof.) (1 January 2001). The Endocrinology of Parturition: Basic Science and Clinical Application. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-3-8055-7195-1.

- ↑ Cheng ZN, Shu Y, Liu ZQ, Wang LS, Ou-Yang DS, Zhou HH (February 2001). "Role of cytochrome P450 in estradiol metabolism in vitro". Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 22 (2): 148–54. PMID 11741520.

- ↑ Hormones, Brain and Behavior. Elsevier. 18 June 2002. pp. 759–761. ISBN 978-0-08-053415-2.

- 1 2 Ginsburg ES, Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Barbieri RL, Teoh SK, Rothman M, Gao X, Sholar JW (December 1996). "Effects of alcohol ingestion on estrogens in postmenopausal women". JAMA. 276 (21): 1747–51. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03540210055034. PMID 8940324.

- 1 2 Sarkola T, Mäkisalo H, Fukunaga T, Eriksson CJ (June 1999). "Acute effect of alcohol on estradiol, estrone, progesterone, prolactin, cortisol, and luteinizing hormone in premenopausal women" (PDF). Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 23 (6): 976–82. PMID 10397281.

- ↑ Leinung MC, Feustel PJ, Joseph J (2018). "Hormonal Treatment of Transgender Women with Oral Estradiol". Transgend Health. 3 (1): 74–81. doi:10.1089/trgh.2017.0035. PMC 5944393. PMID 29756046.

- ↑ Soltysik K, Czekaj P (April 2013). "Membrane estrogen receptors - is it an alternative way of estrogen action?". J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 64 (2): 129–42. PMID 23756388.

- ↑ Prossnitz ER, Barton M (May 2014). "Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 389 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. PMC 4040308. PMID 24530924.

- ↑ Ojasoo T, Raynaud JP (November 1978). "Unique steroid congeners for receptor studies". Cancer Res. 38 (11 Pt 2): 4186–98. PMID 359134.

- ↑ Ojasoo T, Delettré J, Mornon JP, Turpin-VanDycke C, Raynaud JP (1987). "Towards the mapping of the progesterone and androgen receptors". J. Steroid Biochem. 27 (1–3): 255–69. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90317-7. PMID 3695484.

- ↑ Raynaud JP, Bouton MM, Moguilewsky M, Ojasoo T, Philibert D, Beck G, Labrie F, Mornon JP (January 1980). "Steroid hormone receptors and pharmacology". J. Steroid Biochem. 12: 143–57. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(80)90264-2. PMID 7421203.

- ↑ Jennifer E. Dietrich (18 June 2014). Female Puberty: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinicians. Springer. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-1-4939-0912-4.

- ↑ Randy Thornhill; Steven W. Gangestad (25 September 2008). The Evolutionary Biology of Human Female Sexuality. Oxford University Press. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-19-988770-5.

- ↑ Raine-Fenning NJ, Brincat MP, Muscat-Baron Y (2003). "Skin aging and menopause : implications for treatment". Am J Clin Dermatol. 4 (6): 371–8. PMID 12762829.

- ↑ Chris Hayward (31 July 2003). Gender Differences at Puberty. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-521-00165-6.

- 1 2 Shlomo Melmed; Kenneth S. Polonsky; P. Reed Larsen; Henry M. Kronenberg (11 November 2015). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1105–. ISBN 978-0-323-34157-8.

- 1 2 3 Richard E. Jones; Kristin H. Lopez (28 September 2013). Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-0-12-382185-0.

- 1 2 Ethel Sloane (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. pp. 496–. ISBN 0-7668-1142-5.

- 1 2 Tekoa L. King; Mary C. Brucker (25 October 2010). Pharmacology for Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 1022–. ISBN 978-0-7637-5329-0.

- 1 2 David Warshawsky; Joseph R. Landolph Jr. (31 October 2005). Molecular Carcinogenesis and the Molecular Biology of Human Cancer. CRC Press. pp. 457–. ISBN 978-0-203-50343-0.

- ↑ M. Notelovitz; P.A. van Keep (6 December 2012). The Climacteric in Perspective: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress on the Menopause, held at Lake Buena Vista, Florida, October 28–November 2, 1984. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 397, 399. ISBN 978-94-009-4145-8.

[...] following the menopause, circulating estradiol levels decrease from a premenopausal mean of 120 pg/ml to only 13 pg/ml.

- ↑ C. Christian; B. von Schoultz (15 March 1994). Hormone Replacement Therapy: Standardized or Individually Adapted Doses?. CRC Press. pp. 9–16, 60. ISBN 978-1-85070-545-1.

The mean integrated estradiol level during a full 28-day normal cycle is around 80 pg/ml.

- ↑ Eugenio E. Müller; Robert M. MacLeod (6 December 2012). Neuroendocrine Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-1-4612-3554-5.

[...] [premenopausal] mean [estradiol] concentration of 150 pg/ml [...]

- 1 2 3 4 Botros R M B Rizk; Hassan N Sallam (15 June 2012). Clinical Infertility and In Vitro Fertilization. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-93-5025-095-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 897–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis US. 2000. pp. 404–406. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 Fluhmann CF (1938). "Estrogenic Hormones: Their Clinical Usage". Cal West Med. 49 (5): 362–6. PMC 1659459. PMID 18744783.

- ↑ James R. Givens; Garland D. Anderson (1981). Endocrinology of Pregnancy: Based on the Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Symposium on Gynecologic Endocrinology, Held March 3-5, 1980 at the University of Tennessee, Memphis, Tennessee. Year Book Medical Publishers. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-8151-3529-6.

Estetrol (E4) is an estrogen with four hydroxyl groups. More specifically, E4, is 15α-hydroxyestriol.

- ↑ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research On Cancer (2007). Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Menopausal Therapy. World Health Organization. p. 384. ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- 1 2 Archana Desai; Mary Lee (7 May 2007). Gibaldi's Drug Delivery Systems in Pharmaceutical Care. ASHP. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-58528-136-7. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ↑ Rebekah Wang-Cheng; Joan M. Neuner; Vanessa M. Barnabei (2007). Menopause. ACP Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-930513-83-9.

- ↑ Mary Lee; Archana Desai (2007). Gibaldi's Drug Delivery Systems in Pharmaceutical Care. ASHP. pp. 336–. ISBN 978-1-58528-136-7.

- ↑ Nursing2013 Drug Handbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. pp. 528–. ISBN 978-1-4511-5023-0.

- ↑ Vermeulen A (1975). "Longacting steroid preparations". Acta Clin Belg. 30 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1080/17843286.1975.11716973. PMID 1231448.

- ↑ Ravery V, Fizazi K, Oudard S, Drouet L, Eymard JC, Culine S, Gravis G, Hennequin C, Zerbib M (December 2011). "The use of estramustine phosphate in the modern management of advanced prostate cancer". BJU Int. 108 (11): 1782–6. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10201.x. PMID 21756277.

- ↑ Hubert Vaudry; Olivier Kah (25 January 2018). Trends in Comparative Endocrinology and Neurobiology. Frontiers Media SA. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-2-88945-399-3.

- 1 2 Reilly WA (1941). "Estrogens: Their Use in Pediatrics". Cal West Med. 55 (5): 237–9. PMC 1634235. PMID 18746057.

- ↑ Martin PL, Burnier AM, Greaney MO (1972). "Oral menopausal therapy using 17- micronized estradiol. A preliminary study of effectiveness, tolerance and patient preference". Obstet Gynecol. 39 (5): 771–4. PMID 5023261.

- ↑ Rigg LA, Milanes B, Villanueva B, Yen SS (1977). "Efficacy of intravaginal and intranasal administration of micronized estradiol-17beta". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 45 (6): 1261–4. doi:10.1210/jcem-45-6-1261. PMID 591620.

- ↑ Butenandt, A.; Hildebrandt, F. (1931). "Über ein zweites Hormonkrystallisat aus Schwangerenharn und seine physiologischen und chemischen Beziehungen zum krystallisierten Follikelhormon. [Untersuchungen über das weibliche Sexualhormon, 6. Mitteilung.]". Hoppe-Seyler's Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie. 199 (4–6): 243–265. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1931.199.4-6.243. ISSN 0018-4888.

- 1 2 3 Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens I: Physiology and Mechanisms of Action of Estrogens and Antiestrogens. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-3-642-58616-3.

- ↑ Miescher K, Scholz C, Tschopp E (1938). "The activation of female sex hormones: Mono-esters of alpha-oestradiol". Biochem. J. 32 (8): 1273–80. PMC 1264184. PMID 16746750.

- ↑ Walter Sneader (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 195–. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ↑ Oriowo MA, Landgren BM, Stenström B, Diczfalusy E (1980). "A comparison of the pharmacokinetic properties of three estradiol esters". Contraception. 21 (4): 415–24. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(80)80018-7. PMID 7389356.

- ↑ Mosby's GenRx: A Comprehensive Reference for Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs. Mosby. 2001. p. 944. ISBN 978-0-323-00629-3.

- 1 2 I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ↑ http://www.kegg.jp/entry/D00105

- ↑ http://www.wjpps.com/download/article/1412071798.pdf

- ↑ Rowlands, S (2009). "New technologies in contraception". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 116 (2): 230–239. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01985.x. ISSN 1470-0328.

- ↑ Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2097. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ↑ http://www.micromedexsolutions.com

- ↑ http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800038089

- ↑ Pickar JH, Bon C, Amadio JM, Mirkin S, Bernick B (2015). "Pharmacokinetics of the first combination 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule in clinical development for menopausal hormone therapy". Menopause. 22 (12): 1308–16. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000467. PMC 4666011. PMID 25944519.

- ↑ Kaunitz AM, Kaunitz JD (2015). "Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: time for a reality check?". Menopause. 22 (9): 919–20. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000484. PMID 26035149.

- ↑ Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH (February 2016). "Update on medical and regulatory issues pertaining to compounded and FDA-approved drugs, including hormone therapy". Menopause. 23 (2): 215–23. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000523. PMC 4927324. PMID 26418479.

- ↑ Fugh-Berman A, Bythrow J (2007). "Bioidentical hormones for menopausal hormone therapy: variation on a theme". J Gen Intern Med. 22 (7): 1030–4. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0141-4. PMC 2219716. PMID 17549577.

Further reading

- Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens I: Physiology and Mechanisms of Action of Estrogens and Antiestrogens. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-58616-3.

- Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

- Fruzzetti F, Trémollieres F, Bitzer J (2012). "An overview of the development of combined oral contraceptives containing estradiol: focus on estradiol valerate/dienogest". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 28 (5): 400–8. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.662547. PMC 3399636. PMID 22468839.

- Stanczyk FZ, Archer DF, Bhavnani BR (2013). "Ethinyl estradiol and 17β-estradiol in combined oral contraceptives: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and risk assessment". Contraception. 87 (6): 706–27. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.12.011. PMID 23375353.