Lifta

| Lifta | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Deserted homes on the hillside | |

Lifta | |

| Arabic | لفتا |

| Name meaning | Lifta, personal name[1] |

| Also spelled | Lefta |

| Subdistrict | Jerusalem |

| Coordinates | 31°47′43″N 35°11′47″E / 31.79528°N 35.19639°ECoordinates: 31°47′43″N 35°11′47″E / 31.79528°N 35.19639°E |

| Palestine grid | 168/133 |

| Population | 2,958 (1948[2]) |

| Area |

8,743 dunams 8.7 km² |

| Date of depopulation | January 1948[3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current localities | Western suburb of Jerusalem |

| Repopulated dates | 1948–2017 by Jews |

Lifta (Arabic: لفتا; Hebrew: ליפתא, Hebrew: מי נפתוח Mei Neftoach) was a Palestine Arab village on the outskirts of Jerusalem. The population was evacuated during the early part of the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine.[4][5][6] During the war, it was settled by Jewish refugees,[7][8][9][10] who subsequently mostly left in 1969-71, following which parts of the village were used as drug rehabilitation clinic and a high school. It is located on a hillside between the western entrance to Jerusalem and the Romema neighbourhood. In 2012, plans to rebuild the village as an upscale neighborhood were rejected by the Jerusalem District Court.[11] In 2017 the last Jewish residents left Lifta, and the village area is now an Israeli nature reserve.

History

Antiquity

The site was populated since ancient times; "Nephtoah" (Hebrew: נפתח, lit. spring of the corridor) is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as the border between the Israelite tribes of Judah and Benjamin.[12] It was the northernmost demarcation point of the territory of the Tribe of Judah.[13][14][8]

Archaeological remains dating as far back as the Second Iron Age have been found in the village.[8][7][15]

The Romans and Byzantines called it Nephtho, and the Crusaders referred to it as Clepsta.[16] The remains of a court-yard home from the Crusader period remains in the centre of the village.[17]

Ottoman era

In 1596, Lifta was a village in the Ottoman Empire, nahiya (subdistrict) of Jerusalem under the liwa' (district) of Jerusalem, and it had a population of 396. It paid taxes on wheat, barley, olives, fruit orchards and vineyards.[18]

In 1834, a battle took place here, during the revolt of that year. The Egyptian Ibrahim Pasha and his army fought and defeated local rebels, led by Shaykh Qasim al-Ahmad, a prominent local ruler. However, the Qasim al-Ahmad family remained powerful and ruled the region southwest of Nablus from their fortified villages of Deir Istiya and Bayt Wazan some 40 kilometers (25 mi) due north of Lifta.[19] In 1838 Lifta was noted as a Muslim village, located in the Beni Malik area, west of Jerusalem.[20]

In 1863 Victor Guérin described Lifta as being surrounded by gardens of lemon-trees, oranges, figs, pomegranates, alms and apricots.[21] An Ottoman village list of about 1870 indicated 117 houses and a population of 395, though the population count included men, only.[22][23]

The Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine in 1883 described it as a village on the side of a steep hill, with a spring and rock-cut tombs to the south.[24]

In 1896 the population of Lifta was estimated to be about 966 persons.[25]

British Mandate era

In 1917, Lifta surrendered to the British forces with white flags and, as a symbolic gesture, the keys to the village.[26]

In the 1922 census of Palestine, Lifta had a population 1,451, all Muslims,[27] increasing in the 1931 census (when Lifta was counted with "Shneller's Quarter"), to 1,893; 1,844 Muslims, 35 Jews and 14 Christians, in a total of 410 houses.[28]

During the 1929 Palestine riots inhabitants of the village actively participated in the robberies and attacks on nearby Jewish communities.[29][30][31]

In 1945 the population of Lifta was 2,250; 2,230 Muslims and 20 Christians,[32] and the total land area was 8,743 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[33] 3,248 dunams were for cereals,[34] while 324 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[35]

Prior to 1948, the village had a modern clinic, two coffeehouses, two carpentry shops, barbershops, a butcher, and a mosque.[8]

In the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine Lifta, Romema, and Shaykh Badr which were strategically located on the road leaving Jerusalem to Tel-Aviv, were an operational priority for Jewish forces. On 4 December 1947, Lifta became one of the first places from which some Arabs evacuated, when some women and children evacuated from Lifta after being told by Arab authorities to make room to house a military company. by mid December irregular Arab militia took up positions in Lifta to defend the site and to harass adjacent Jewish areas. Hagannah patrols engaged in firefights with the village militiamen while Irgun and Lehi were even more aggressive. On 28 December, following a machine-gun and grenade attack on a cafe in Lifta or Romema[lower-alpha 1] that left seven dead, more women and children left the village. The village was suffering from food shortages in the beginning of January. Subsequently, they returned home, and were then ordered to evacuate again by Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni who was visiting the village. On 29 January, a Lehi raid blew up 3 houses in the village. By early February the village was abandoned by the irregular militia. Concurrent to the events in Lifta, similar violence occurred in adjacent Romema.[4][5][6]

State of Israel

Lifta was used for Jewish refugee housing during the war, and following the war the Jewish Agency and the state of Israel settled Jewish immigrants from Yemen and Kurdistan in the village, totaling 300 families. However ownership of the houses was not registered in their name. Living conditions in Lifta were difficult, the buildings were in poor repair, poor roads and transport, and lack of electricity, water, and sanitation infrastructure.[7][8][9][10] In 1969-71 most of the Jewish inhabitants of Lifta chose to leave as part of a compensation program by Amidar. Holes were drilled in the roofs of the evacuated buildings to make them less inhabitable, so that squatters wouldn't take up residence. 13 families, who lived in the portion of the village close to Highway 1 and didn't suffer from transportation issues chose to remain.[36]

Following the departure of the Jewish residents, some of the buildings in the village were used for Lifta drug abuse rehabilitation center for adolescents, which was closed in 2014,[37] and from 1971 for the Lifta high school, an open education school, which relocated to German Colony, Jerusalem in 2001.[38]

In 1984, one of the abandoned buildings in the village was occupied by the "Lifta gang", a Jewish group plotting the blow up the mosques on the Temple Mount, who were stopped at the gates of the temple mount with 250 pounds of explosives, hand grenades, and other armament.[39][40]

In 2011, plans were announced to demolish the village and build a luxury development consisting of 212 luxury housing units and a hotel.[41] Former residents brought a legal petition to preserve the village as a historic site.[42] Lifta was the last remaining Arab village that was depopulated to have not been either completely destroyed or re-inhabited.[41] By 2011, three books about the Palestinian village history had been published.[43]

In the 1980s, was declared a municipal nature reserve under the auspices of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.[44][45] In June 2017 the last Jewish residents left the village following a settlement with the government who acknowledged they were not squatters but rather resettled in Lifta by the appropriate authorities.[46] In July 2017 Mei Neftoach was declared a national nature reserve.[47] 55 out of 450 pre-1948 stone houses are still standing.[48][8]

Culture

Lifta was among the wealthiest communities in the Jerusalem area, and the women were known for their fine embroidery[49] Thob Ghabani bridal dresses were sewn in Lifta. They were made of ghabani, a natural cotton covered with gold color silk floral embroidery produced in Aleppo, and were narrower than other dresses. The sleeves were also more tapered. The sides, sleeves and chest panel of the dress were adorned with silk insets. The dresses were ordered by brides in Bethlehem.[50] The married women of Lifta wore a distinctive conical shaṭweh head-dress that was also worn in Bethlehem, Ayn Karim, Beit Jala and Beit Sahour.[51]

See also

- Ali Abunimah

- List of modern names for biblical place names

- Palestinian costumes

- Rasmea Odeh

- Yahya Hammuda

- Zochrot

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lifta. |

References

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 322

- ↑ Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Archived 12 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. also gives village area

- ↑ Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #363

- 1 2 Morris, 2004, pp. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Morris, 2004, pp 119-120]

- 1 2 The De-Arabization of West Jerusalem 1947-50, Nathan Krystall, Journal of Palestine Studies, pp. 5-22

- 1 2 Krystall, Nathan. "The Fall of the New City 1947-1950." The Institute of Jerusalem Studies, Jerusalem. Badil Resource Center. Bethlehem (1999).

- 1 2 3 Lifta Documentation and Initial Survey (in Hebrew), 2013, Israeli Antiquities Authority]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lifta and the Regime of Forgetting: Memory Work and Conservation, Daphna Golan, Zvika Orr, Sami Ershied, Jerusalem Quarterly, 2013, Vol. 54, pp 69-81

- 1 2 Jerusalem 'Squatter' Discovers That His Home Is Rightfully His, Ha'aretz, 10 February 2012

- 1 2 The Kenesset discusses eviction of Lifta residents: "the immigrants from Arab countries were called squatters and the Kibutniks - settlers" (in Hebrew), TheMarker, 25 January 2016

- ↑ Court rules against demolition of empty Lifta homes

- ↑ Maisler, Benjamin (1932). "A Memo of the National Committee to the Government of the Land of Israel on the Method of Spelling Transliterated Geographical and Personal Names, plus Two Lists of Geographical Names". Lĕšonénu: A Journal for the Study of the Hebrew Language and Cognate Subjects (in Hebrew). 4 (3): 51. JSTOR 24384308.

- ↑ MikraNet, mikranet.cet.ac.il; accessed 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Nephtoah Bible Dictionary

- ↑ Lifta, Archaeological Annex to Development plan, 2003 Israeli Antiquities Authority

- ↑ Heritage conservation in Israel: Lifta

- ↑ Pringle, 1997, p. 66

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 115. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 301

- ↑ Khalidi, 1992, p. 301

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 123

- ↑ Guérin, 1868, pp. 252-256

- ↑ Socin, 1879, p. 157

- ↑ Hartmann, 1883, p. 118, also noted 117 houses

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, III:18. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 301

- ↑ Schick, 1896, p. 126

- ↑ Gilbert, 1936, pp. 157-68

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 41

- ↑ Halamish, Aviva (1994). ירושלים לדורותיה [Jerusalem through the Ages] (in Hebrew). Open University of Israel. p. 83.

ערבים מכפרי הסביבה - ליפתא, דיר יאסין, עין כרם, מלחה, בית צפאפא, צור באהר וסילואן - ובדווים ממדבר יהודה תקפו בנשק חם את שכונות הספר היהודיות של ירושלים [Arabs from the surrounding villages - Lifta, Dir Yasin, Ein Karem, Makcha, Beit Tsfafa, Tsur Baher and Silwan - and Bedouin from the Yehuda desert attacked the Jewish neighborhoods of Jerusalem with guns]

- ↑ Eliav, Binyamin, ed. (1976). היישוב בימי הבית הלאומי [The Settlement in the Days of the National Home] (in Hebrew). Keter Publishing House. p. 38.

לאחר דין ודברים עם השוטרים הותר לקבוצת ערבים מכפר ליפתא לחזור לכפרם דרך רחוב יפו. בהגיעם לרחוב פתחו הליפתאים מיד בשוד החנויות ובפגיעות ביהודים [After discussion with the police, a group of Arabs from Lifta was allowed to return to their village via Yaffa Street. Once there, they right away started looting the shops and attacking Jews]

- ↑ Dinur, Ben Tzion, ed. (1964). ספר תולדות ההגנה [The Haganah Book] (in Hebrew). volume 2 part 1. Maarachot. p. 316.

וקבוצה אחת בפיקודו של המוכתר מליפתא עלתה על גג והמטירה אש על רחוב יפו [and one group under the command of the Mukhtar of Lifta rained down fire on Yaffa Street]

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 57

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 103

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 153

- ↑ from Settlers to squatters - the classification of residents in absentee property as squatters is injust, Lifta as an example (in Hebrew), Black Labor, Yoni Yochanan, 11 September 2016

- ↑ Despite the economic improvement, Drug rehabilitation center for adolescents in Lifta to close (in Hebrew), Haaretz, 22 May 2014

- ↑ Lifta High School: History, Lifta High School

- ↑ Discourse and Palestine: Power, Text and Context, Annelies Moors, page 133

- ↑ Ground Zero: Jerusalem, Holy War, and Collective Insanity, Jerry Kroth, page 131

- 1 2 "Israel moves to turn deserted Palestinian village into luxury housing project", Haaretz.com, 21 January 2011.

- ↑ Knell, Yolande (30 May 2011). "Legal battle over an abandoned Palestinian village". BBC. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ Davis, 2011, p. 30

- ↑ INPA Raises Lifta Security to Prevent Willow Theft, Jerusalem Post, September 19, 2011

- ↑ Mei Neftoach (Lifta) (in Hebrew, Mapa, encyclopedia entry

- ↑ Defeated in Court, Lifta's Last Families to Leave Their Jerusalem-area Homes, Ha'aretz, 22 June 2017

- ↑ According to the law of nature: four new reserves in Israel, Yisrael Hayom, 4 July 2017

- ↑ Esther Zandberg,Unofficial monument to a decisive time in history, Haaretz.com, 25 November 2004; accessed 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Woven legacy, woven language, Saudi Aramco World, Volume 42, Number 1.

- ↑ Stillman, 1979, pp. 42, 44 (ill.)

- ↑ Stillman, 1979, p. 37

- ↑ Some sources place the cafe in Lifta (Morriss 2004), and some in Romema (Krystall 1999) - which are adjacent to each other

Bibliography

- Avner, Rina (18 January 2008). "Jerusalem, Lifta Final Report" (120). Hadashot Arkheologiyot–Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Barclay, James Turner (1858). The city of Great King; or, Jerusalem as it was. Philadelphia: J. Challen and sons [etc.] (p. 544)

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dagan, Yehuda; Barda, Leticia (2010-12-26). "Jerusalem, Lifta Survey Final Report" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4. (p. 900)

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Gilbert, Major Vivian (1936): The Romance of the last Crusade, London, UK

- Guérin, Victor (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, Sami (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Haiman, Mordechai (19 September 2011). "Jerusalem, Lifta Final Report" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, Walid (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R.E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetteer. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521460107.

- Robinson, Edward; Smith, Eli (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Schölch, Alexander (1993). Palestine in Transformation, 1856-1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development. Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 978-0-88728-234-8.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Stillman, Yedida Kalfon (1979). Palestinian Costume and Jewelry. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0490-7. (A catalog of the MOIFA (Museum of International Folk Art at Santa Fe's) collection of Palestinian clothing and jewellery.)

- Tobler, Titus (1854). Dr. Titus Toblers zwei Bucher Topographie von Jerusalem und seinen Umgebungen (in German). 2. Berlin: G. Reimer. (pp. 758-60; cited in Pringle, 1997, p. 66)

- Zelinger, Yehiel (18 September 2011). "Jerusalem, Lifta, Final Report" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

External links

- , The Ruins of Lifta (2016)

- Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem, Lifta, Survey (2010)

- Welcome to Lifta, palestineremembered.com; accessed 2 September 2015.

- Lifta, Zochrot

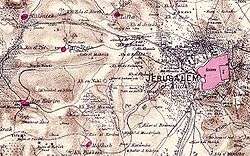

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Lifta in Antiquity Archaeological Survey of Israel

- F.A.S.T.-Lifta Preservation Joint project on the reconstruction of memory and the preservation of Lifta, archive.org, 14 May 2006.

- Lifta photos by Dr Moslih Kanaaneh, jalili48.com; accessed 2 September 2015.

- Lifta, by Rami Nashashibi (1996), Center for Research and Documentation of Palestinian Society.

- Lifta, zochrot.org

- Return to Lifta, 13 May 2006, zochrot.org

- Lifta Society website, liftasociety.org

- Lifta website, schulen.eduhi.at

- 3D models of different houses in Lifta, sketchfab.com; accessed 2 September 2015.