Sur Baher

Sur Baher

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • Also spelled | Tsur Baher (unofficial) |

|

Sur Baher | |

Sur Baher | |

| Coordinates: 31°44′14″N 35°13′59″E / 31.73722°N 35.23306°ECoordinates: 31°44′14″N 35°13′59″E / 31.73722°N 35.23306°E | |

| Grid position | 172/127 PAL |

| District |

|

| Population (2006) | |

| • Total | 15,000 |

| Name meaning | The wall of Bahir (Prominent)[1] |

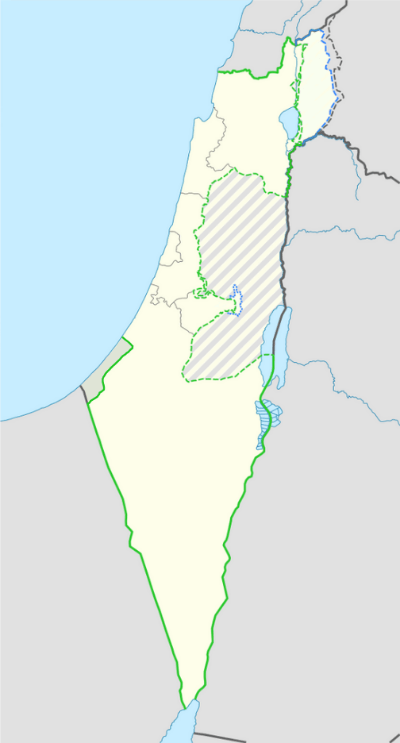

Sur Baher (Arabic: صور باهر, Hebrew: צור באהר), also Tsur Baher, is a Palestinian neighborhood on the southeastern outskirts of East Jerusalem. It is located east of Ramat Rachel and northeast of Har Homa. In 2006, Sur Baher had a population of 15,000.[2]

History

During a general survey of the southern part of Sur Baher, ancient stone cut olive presses, wine presses, cisterns and a limekiln were found.[3] A cave, with remains dating to the Iron Age I (12-11th centuries B.C.E.) were excavated at Khirbat Za‛kuka, south of Sur Baher.[4]

A burial cave, dating to the end of the first century BCE and the first century CE have also been excavated. The cave contained remains of several ossuaries, in addition to arcosolia and benches.[5]

Pottery vessels that dated to the Late Roman and Byzantine periods were excavated from an ancient quarry at Sur Baher.[6]

In the Crusader era it was known as Casale Sorbael.[7][8] In 1179 the village was mentioned as being among the villages whose revenue were given to the Mt. Zion Abbey by Pope Alexander III.[9]

1517–1920: Ottoman era

Sur Baher, like the rest of Palestine, was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517, and in the tax registers of 1596 "Sur Bahir" appeared as being in the Nahiya of Quds in the Liwa of Quds. It had a population of 29 households, all Muslim. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 33,3 % on agricultural products, including wheat barley, vineyards and fruit trees, goats and beehives; a total of 12,983 Akçe. 15/24 of the revenues went to a waqf.[10][11]

In 1838, Edward Robinson noted Sur Bahil N 13° E from Tuqu'.[12] It was further noted as a Muslim village.[13]

French explorer Victor Guérin visited the place in 1863, and described Sur Baher as having about 400 inhabitants.[14] An Ottoman village list of about 1870 found 46 houses and a population of 154, though the population count included men, only. It further noted that it was an old, well-built and nice-looking village.[15][16]

In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Sur Bahir as "a stone village of moderate size, on a bare hill. On the north is a well in the valley, and there are rock-cut tombs above it to the west."[17]

In 1896 the population of Sur Bahir was estimated to be about 300 persons.[18]

1920–1948: British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Sur Baher had an all Muslim population of 993 persons.[19] In the 1931 census the population of Sur Bahir was a total of 1529, still all Muslim, in 308 inhabited houses.[20]

In 1945 the population of Sur Baher, together with Umm Tuba, was 2,450, all Muslims,[21] who owned 8,915 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[22] 911 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 3,927 used for cereals,[23] while 56 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[24]

1948–1967: Jordanian era

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Sur Baher, along with the rest of the West Bank, was occupied and later annexed by Jordan.[25]

In the 1961 Jordanian census, the population of Sur Baher was 2,335.[26] Sur Baher's population together with Umm Tuba and Arab el Subeira amounted to 4,012 in the same census.[27]

1967–present: Israeli occupation

Israel captured Sur Baher from Jordan in 1967, during the Six-Day War. Sur Baher has been occupied by Israel ever since.

The 1967 Israeli census showed there were 4,710 inhabitants, an increase with 17.4%.[27]

In 1970, Israel expropriated land around the village used for livestock grazing and harvesting olive and citrus groves from its owners.[28] Most of that land was utilized in the building of the Jerusalem Jewish neighborhood of East Talpiot.[28] According to Isabel Kershner, a fifth of Sur Baher's land was expropriated for East Talpiot, available land in the village became insufficient to meet the growing needs of the population, and it was difficult for Sur Baher residents to obtain building permits from the Jerusalem Municipality.[29] Residents constructed homes on the remaining land in the Wadi al-Ain and Wadi al-Humus valleys across what is designated by Israel as the municipal border.[29]

In 2000, the Israeli government and Jerusalem municipality approved building plans for two new high schools and a youth center. In September 2005, the Jerusalem municipality, in cooperation with the Israel Defense Forces, cleared a Jordanian minefield in Sur Baher. The work, carried out by an Israeli company, was completed by October 2005.[2] In May 2007, the municipality built two schools on the cleared land: a girls school attended by 800 students, and Ibn Rushd, a boys school attended by 700 students.[30] Since 2013, even non-Israeli Palestinian residents of Sur Baher are entitled to the services of Bituah Leumi (the Israeli National Insurance Institute) and the associated state health care.[31]

Notable residents

- Yohanan Elihai/Jean Leroy,[32] a Catholic monk, and expert on the Palestinian dialect of Arabic

References

- ↑ Palmer 1881, p. 329

- 1 2 Minefield as a School Ground: The Tzur Baher Minefield Clearance Project, by Bentzi Telefus

- ↑ Dagan, Barda and ‘Adawi, 2009, Jerusalem, Sur Bahir, Survey Final Report

- ↑ ‘Adawi, 2014, Jerusalem, Khirbat Za‘kuka (Sur Bahir) Final Report

- ↑ Ganor and Klein, 2011, Sur Bahir, Survey Final Report

- ↑ ‘Adawi, 2010, Jerusalem, Sur Bahir, Final Report

- ↑ Rey, 1883, p. 391

- ↑ Röhricht, 1887, p. 221

- ↑ Röhricht, 1893, RRH, pp. 153-154, No. 576

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 120.

- ↑ Toledano, 1984, p. 299, gives Sur Bahir‘s position as 31°44′15″N 35°13′40″E

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, p. 183

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 122

- ↑ Guérin, 1869, p. 83

- ↑ Socin, 1879, p. 161

- ↑ Hartmann, 1883, p. 124 also noted 46 houses

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 30

- ↑ Schick, 1896, p. 125

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p 44

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 58

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 104

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 154

- ↑ Yoram Dinstein; Mala Tabory (1 September 1994). Israel Yearbook on Human Rights: 1993. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7923-2581-9. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

Israel considers Jordan’s annexation of the West Bank, recognised only by Great Britain and Pakistan, to have been illegal.

- ↑ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 14

- 1 2 Volume 6 Table A - Comparison between 1967 (Israeli) and 1961 (Jordanian) census, Levy Economics Institute

- 1 2 Amir S. Cheshin; Bill Hutman; Avi Melamed (2001). Separate and Unequal: The Inside Story of Israeli Rule in East Jerusalem. Harvard University Press. pp. 35–37. ISBN 9780674005532.

- 1 2 Kershner, 2005, p. 143-145

- ↑ Arnona 2008, newsletter published by the public relations department of the Jerusalem Municipality http://www.jerusalem.muni.il Archived 2006-11-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Social benefits for Palestinians in Sur Baher, Hadoar". Jpost Inc. 18 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ Yohanan Elihai/Jean Leroy

Bibliography

- ‘Adawi, Zubair (2010-01-19). "Jerusalem, Sur Bahir, Final Report" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- ‘Adawi, Zubair (2014-08-07). "Jerusalem, Khirbat Za'kuka (Sur Bahir) Final Report" (126). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C. S. (1899). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. 1. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 457 -459)

- Conder, C. R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dagan, Yehuda; Barda, Leticia; ‘Adawi, Zubair (2009-12-13). "Jerusalem, Sur Bahir, Survey Final Report" (121). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Ganor, Amir; Klein, Alon (2011-09-12). "Sur Bahir, Survey Final Report" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Kershner, I. (2005). Barrier: The Seam of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Macmillan. p. 143-145. ISBN 9781403968012.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rey, E. G. (1883). Les colonies franques de Syrie aux XIIme et XIIIme siècles (in French). Paris: A. Picard.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Röhricht, R. (1887). "Studien zur mittelalterlichen Geographie und Topographie Syriens". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (in German). Leipzig: K. Baedeker. 10: 195–344.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Toledano, E. (1984). "The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population". Archivum Ottomanicum. 9: 279–319.

External links

- Welcome To Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Sur Bahir and Umm Tuba (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ)

- Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile, ARIJ

- Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba - aerial photo, ARIJ

- Sur Baher on Facebook

- Wandering in Sur Baher on I'm from Jerusalem website