Kuwaykat

| Kuwaykat | |

|---|---|

|

Sheikh Abu Muhammad tomb | |

Kuwaykat | |

| Arabic | كويكات |

| Name meaning | "Huts" (possibly)[1] |

| Subdistrict | Acre |

| Coordinates | 32°58′16″N 35°08′48″E / 32.97111°N 35.14667°ECoordinates: 32°58′16″N 35°08′48″E / 32.97111°N 35.14667°E |

| Palestine grid | 164/264 |

| Population | 1,050[2][3] (1945) |

| Area | 4,733[3] dunams |

| Date of depopulation | 10 July 1948[4] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current localities | Beit HaEmek[5][6] |

Kuwaykat (Arabic: كويكات), also spelled Kuweikat, Kweikat or Kuwaikat, was a Palestinian village located 9 km northeast of Acre. It was depopulated in 1948.

History

The old khan (caravansary) in Kuwaykat possibly dated to the Crusader period or an earlier date. According to historian Denys Pringle, the khan might have been part of the headquarters of Genoese estate in the village built in the 13th century. It consisted of a round barrel-vaulted building made of ashlar.[7]

In 1245, it was noted that western part of Kuwaykat was owned by the Church and Hospital of St Thomas the Martyr in Acre.[8]

Ottoman era

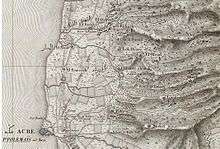

In the late Ottoman period, Kuwaykat was named Chiouwe chiateh on the French map Pierre Jacotin made of the area during Napoleon's invasion of 1799.[9] In 1875 Victor Guérin visited, and found the village surrounded with gardens planted with fig and olive trees, and with an ancient well. He further noted that the village was mentioned in Crusader sources.[10] In 1881 Kuwaykat was described by the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine as being built of stone and situated at the foot of hills. The roughly 300 Muslim residents cultivated olives.[11] In 1887, an elementary school was built in the village. In addition, the village had a mosque and a shrine for the Druze religious leader, Shaykh Aby Muhammad al-Qurayshi.[6]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Kiryet et Kuweikat had about 565 inhabitants; all Muslims.[12]

British Mandate period

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Kuaikat had a population of 604; all Muslims,[13] increasing in the 1931 census to 789, still all Muslims, in a total of 163 houses.[14]

In April 1938, during the Palestinian Arab revolt against the British Mandatory authorities which began in 1936, rebels planted a mine on the Yarka road between Kuwaykat and Kafr Yasif which blew up a passing British Army vehicle, killing nine soldiers (Arab version) or one Royal Ulster rifleman, with two other soldiers wounded (British archive version). The rebel leader of Kuwaykat, Fayyad Baytam, was approached by regional rebel commander Shaykh Amhad al-Tuba to plant the explosive, but Baytam refused, wary of the consequences Kuwaykat would suffer should the British attack the village. Al-Tuba and Ali Hammuda of Tarshiha placed the mine instead. Following the attack, British forces initially blamed the residents of nearby Kafr Yasif and set fire to the village, resulting in wide scale destruction. When one of Kafr Yasif's residents informed the British soldiers that the village was not involved and the rebels had come from Kuwaykat, the British proceeded to surround and attack that village. Some young men left their homes and entered the streets and were subsequently shot dead and the village mosque, where several men had taken shelter, was raided. The men inside were removed and then killed by British soldiers. Nine men were killed, including a resident of Sabalan. According to anthropologist Ted Swedenburg, the incident in Kuwaykat was "an example of bloodletting that are largely invisible from published Western or Israeli accounts of the revolt." The British later denied that its soldiers were involved in the incident.[15]

By 1945, Kuwaykat had 1,050 Muslim inhabitants,[2] with a total of 4,733 dunums (1,170 acres) of land according to an official land and population survey.[3] The land of Kuwaykat was considered to be among the most fertile of the district. Grain, olives and watermelons were its chief crops. In 1944/45 a total of 3,316 dunums were used for cereals, and 1,246 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards, of which 500 dunums were planted with olive trees,[16] while 26 dunams were built-up (urban) area.[17] The villagers also engaged in livestock breeding and dairy production. The village had a population of 1,050.[6]

1948 War and aftermath

The first attack on the village of Kuwaykat during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War took place on 18–19 January 1948, and involved a force of over eighty Jewish militiamen, according to Filastin, the Palestinian newspaper at the time. The attack was repulsed, as was another attack on the village on the night of 6–7 February.[6][18] The village was finally depopulated during a military assault by Israel's Sheva' Brigade and Carmeli Brigade, as part of Operation Dekel. On the night of 9 July, at the start of the offensive, the village came under heavy bombardment.[6] Villagers interviewed in 1973 in the refugee camp of Bourj el-Barajneh in Lebanon recalled:

We were awakened by the loudest noise we had ever heard, shells exploding and artillery fire [..] women were screaming, children were crying...Most of the villagers began to flee with their pajamas on. The wife of Qassim Ahmad Sa´id fled carrying a pillow in her arms instead of her child ...[6][19]

Two people were killed and two wounded by the shelling. Many villagers fled to Abu Snan, Kafr Yasif and other villages that later surrendered. Those, mostly elderly, villagers who remained in Kuwaykat, were soon expelled to Kafr Yasif.[6] In January 1949, kibbutz ha-Bonim (later renamed Beit HaEmek) was established near the site of Kuwaykat, on village lands.[20] Its settlers were Jewish immigrants from England, Hungary and the Netherlands.[6] The Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi described the village in 1992:

Little remains of the village except the deserted cemetery, completely overgrown with weeds, and rubble from houses. Inscriptions on two of the graves identify one as that of Hamad 'Isa al-Hajj, and another as that of Shaykh Salih Iskandar, who died in 1940. The shrine of Shaykh Abu Muhammad al-Qurayshi still stands but its stone pedestal is badly cracked.[6]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 51

- 1 2 Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 4

- 1 2 3 Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 40

- ↑ Morris, 2004, p. xvii, village #86. Also gives cause of depopulation

- ↑ Morris, 2004, p. xxi, settlement #45, January 1949

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Khalidi, 1992, p. 22

- ↑ Pringle, 1997, p. 64

- ↑ Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 301, No. 1135; Cited in Pringle, 2009, p. 163

- 1 2 Karmon, 1960, p. 162

- ↑ Guérin, 1880, p. 29

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 147. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 22

- ↑ Schumacher, 1888, p. 173

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Acre, p. 36

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 101

- ↑ Swedenburg, 2003, pp. 107-108. The names of those killed are Ali Baytam, Salih Sanunu, Muhammad Muhammad al-Husayn, Ali al-Safadi, Ali Husayn At'ut, Muhammad Khalil At'ut, Muhammad Salih Iskandar, Ahmad al-'Abaday and unnamed person from Sabalan.

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 81

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 131

- ↑ Filastin, 21.01.1948 and 08.02.1948

- ↑ Nazzal, 1978, pp. 72-73

- ↑ Morris, 1987, p. 187

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, H. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, Victor (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 3: Galilee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, Sami (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Khalidi, Walid (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, Benny (1987). The Birth of the Palestinian refugee problem, 1947-1949. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33028-9.

- Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7.

- Nazzal, Nafez (1978). The Palestinian Exodus from Galilee 1948. The Institute for Palestine Studies. pp. 24, 71–74, 100.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521 46010 7.

- Pringle, Denys (2009). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: The cities of Acre and Tyre with Addenda and Corrigenda to Volumes I-III. IV. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85148-0.

- Röhricht, Reinhold (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Swedenburg, Ted (2003). Memories of Revolt: The 1936–1939 Rebellion and the Palestinian National Past. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1610752635.

External links

- Welcome to Kuwaykat Palestine Remembered

- Kuwaykat, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 3: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Kuwaykat from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Al-Kweikat Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

- Tour to Kuwykat -Raneen Geries 6.9.2008, Zochrot