Motza

Motza (or Motsa) (Hebrew: מוֹצָא) is a neighbourhood on the western edge of Jerusalem, Israel. It is located in the Judean Hills, 600 metres above sea level, connected to Jerusalem by the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv highway and the winding mountain road to Har Nof. Established in 1854, Motza was the first Jewish farm founded outside the walls of the Old City in the modern era. It is believed to be located on the site of a Biblical village of the same name mentioned in Joshua 18:26.[2]

History

.jpg)

Jewish settlement in the Late Ottoman period (1854-1917)

In 1854, farmland was purchased from the nearby Arab village of Qalunya (Colonia) by a Baghdadi Jew, Shaul Yehuda, with the aid of British consul James Finn. A B'nai B'rith official signed a contract with the residents of Motza residents that enabled them to pay for the land in long-term payments.[3][4] Four Jewish families settled there. One family established a tile factory which was one of the earliest industries in the region. In 1871, while plowing his fields, one of the residents, Yehoshua Yellin, discovered a large subterranean hall from the Byzantine period that he turned into a travellers' inn which provided overnight shelter for pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem.

When Theodor Herzl visited Palestine in 1898, he passed through Motza, which then had a population of 200. Captivated by the landscape, he planted a cypress tree on the hill. After he died in 1904 at the ago of 44, it became an annual pilgrimage site by Zionist youth, who planted more trees around Herzl's tree.[5] During World War I, Herzl's tree was cut down by the Turks who were levelling forests for firewood and supplies.[5]

British Mandate period

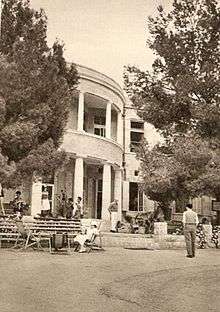

David Remez named the sanatorium opened in the village Arza, or cedar, in reference to Herzl's tree.[6] Arza, established in the 1920s, was the first Jewish "health resort" in the country.[7]

Motza was violently attacked in the 1929 Palestine riots (see below),[3][8][9] and was abandoned for one year by its Jewish inhabitants.[9]

The flourishing orchard of the Broza family is mentioned in the Hope Simpson Report in 1930.[10] The children of Motza attended school in one of the rooms built above the vaulted hall. Their teacher was Moshe David Gaon, later father of singer and actor Yehoram Gaon. Motza was the only Jewish presence in the area. Kfar Uria and Hartuv were further west in the Judean foothills.[3][11][12]

According to a census conducted in 1931 by the British Mandate authorities, Motza had a population of 151 inhabitants, in 20 houses.[13]

In 1933 the villagers founded the neighbouring Upper Motza (Motza Illit).

In December 1948, United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 recommended that "the built-up area of Motsa" be included in the Jerusalem "Corpus separatum", which was to be detached from "the rest of Palestine" and "placed under effective United Nations control". However, like other provisions of Resolution 194, this was never carried out in practice, and Motza became part of the State of Israel.

1929 murders

Despite good relations with neighbouring Arab communities, the village was attacked during the 1929 Palestine riots. Several residents of Qalunya attacked an outlying house belonging to the Makleff family, killing the father, mother, son, two daughters, and their two guests. Three children survived by escaping out a second-story window; one, Mordechai Maklef, later became Chief of Staff of the Israeli Army. The attackers included the lone police officer and armed man in the area, as well as a shepherd employed by the Makleff family. The village was subsequently abandoned by Jews for a year's time.[9]

Refugees from Motza sent a letter to the Refugees Aid Committee in Jerusalem describing their plight and asking for help: "Our houses were burned and robbed...we have nothing left. And now we are naked and without food. We need your immediate assistance and ask for nothing more than bread to eat and clothes to wear." [14]

In the Bible (Old and New Testament)

Biblical Motza is listed among the Benjamite cities of Joshua 18:26. It was referred to in the Talmud as a place where people would come to cut young willow branches as a part of the celebration of Sukkot (Mishnah, Sukkah 4.5: 178).

Motza was identified as the Emmaus of Luke in 1881 by William F. Birch (1840-1916) of the Palestine Exploration Fund, and again in 1893 by Paulo Savi.[15] Excavations in 2001-2003 headed by Professor Carsten Peter Thiede let him conclude that Khirbet Mizza/Tel Moza was the only credible candidate for biblical Emmaus.[16]

Archaeology

Excavations in Motza (2012) unearthed the Tel Motza temple, a large building revealing clear elements of ritual use, dated to the 9th century BCE. A rare cache of ritual objects found near the building included tiny ceramic figurines of men and animals. An analysis of animal bones found at the site indicated that they belonged only to kosher animals.[17]

Archaeologists also found remains of a settlement dated to the Neolithic period (about 6000 BCE), a settlement from the First Temple period and 36 wheat granaries, indicating that Motza was part of an ancient economic center.[18]

Landmarks

Motza was home to one of Israel's oldest wineries, the Teperberg Winery, then called Efrat, until its move to Tzora.[19]

In 2006, the Yellin and Yehuda families helped restore Joshua Yellin's original home, among the oldest and most derelict buildings at the site.[20]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Motza. |

- ↑ "Das Palästina-bilder-buch; 96 photographien". Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ National Campus for the Archeology of Israel Archived 2007-12-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Motza, Atarot, and Neveh Yaacov

- ↑ לגרב ימ בכרב ימ

- 1 2 Planting from the remains

- ↑ Modern pilgrimage

- ↑ How Israel's socialist retreats for workers turned into luxury hotels

- ↑ Ancient Motza

- 1 2 3 Segev, Tom (1999). One Palestine, Complete. Metropolitan Books. p. 324. ISBN 0-8050-4848-0.

- ↑ "Hope Simpson Report". Archived from the original on 2008-01-26. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ↑ Herzl's Tree Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ סיפור הפרברים: חמישה אתרים בשולי ירושלים

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 41

- ↑ Jewish memorabilia to be auctioned in Jerusalem, Haaretz

- ↑ W. F. Birch, "Emmaus", Palestine Exploration Fund, Quarterly Statement 13 (1881), pp. 237-38; Paulo Savi, "Emmaus", Revue Biblique 2 (1893), pp. 223-27.

- ↑ Thiede, Carsten Peter (2005). "Die Wiederentdeckung von Emmaus bei Jerusalem" [Rediscovering Emmaus near Jerusalem]. Zeitschrift für antikes Christentum (in German). Walter de Gruyter. 8: 593–599. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ Israeli archaeologists uncover ancient temple just outside Jerusalem

- ↑ The long road to straightening out a curve

- ↑ Rogov, Daniel (2012). The Ultimate Rogov's Guide to Israeli Wine. Toby Press. p. 550.

- ↑ עבודות שיפוץ ושימור לבית משפחת ילין במוצא

1*"Talking Picture Magazine", March 1933, p. 45, an article on the film: "THE MOTZA COLONY", a drama after the event of the brutal murder of the Makleff Family.

External links

- Motza history on Haim Zippori centre for community education (in Hebrew)

- Motza Valley (in Hebrew)

Coordinates: 31°47′38.11″N 35°10′6.45″E / 31.7939194°N 35.1684583°E