Crusader states

The Crusader states, also known as Outremer, were a number of mostly 12th- and 13th-century feudal Christian states created by Western European crusaders in Asia Minor, Greece and the Holy Land, and during the Northern Crusades in the eastern Baltic area. The name also refers to other territorial gains (often small and short-lived) made by medieval Christendom against Muslim and pagan adversaries.

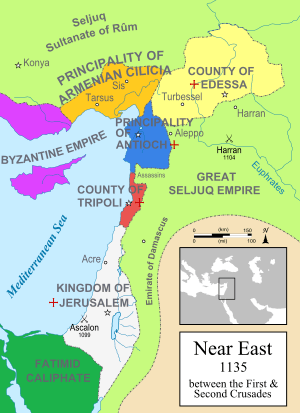

The Crusader states in the Levant were the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli and the County of Edessa.[1] The people of the Crusader states were generally referred to as "Latins ".[2]

Background

Beginning in the 7th century, Muslim rulers began expanding their territories into Christian Roman/Byzantine lands, conquering Egypt and the Levant, and gradually taking over all of North Africa, much of Southwest Asia, and most of the Iberian Peninsula. The Eastern Romans, or Byzantines, partially recovered lost territory on numerous occasions but gradually lost all but Anatolia and parts of Thrace and the Balkans. In the West, the Roman Catholic kingdoms of northern Iberia launched campaigns known as the Reconquista to reconquer the peninsula from the Arabized Berbers known as Moors (who called it al-Andalus). The conquered Iberian principalities are not customarily called Crusader states, except for the Kingdom of Valencia, despite fitting the criteria.[3]

Malcolm Barber, a British scholar of medieval history, indicates that, in the Crusader state of the Kingdom of Jerusalem the Holy Sepulchre was added to in the 7th century and rebuilt in 1022, "after a previous collapse". "In 691–2 Caliph Abd al Malik had built a great dome over the rock here, a place sacred to all three great religions". [4]

In 1071, the Byzantine army was defeated by the Muslim Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert, resulting in the loss of most of Asia Minor. The situation was a serious threat to the future the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire. The Emperor sent a plea to the Pope in Rome to send military aid to restore the lost territories to Christian rule. The result was a series of western European military campaigns into the eastern Mediterranean, known as the Crusades. Unfortunately for the Byzantines, the crusaders had no allegiance to the Byzantine Emperor and established their own states in the conquered regions, including the heart of the Byzantine Empire.

First Crusade

The first four Crusader states were created in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade:

- The first Crusader state, the County of Edessa, was founded in 1098 and lasted until 1150.

- The Principality of Antioch, founded in 1098, lasted until 1268.

- The Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded in 1099, lasted until 1291, when the city of Acre fell. There were also many vassals of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the four major lordships (seigneuries) being:

- The County of Tripoli, founded in 1104, with Tripoli itself conquered in 1109, lasted until 1289.

After the First Crusade's capture of Jerusalem and victory at Ascalon the majority of the Crusaders considered their pilgrimage complete and returned to Europe. Godfrey was left with only 300 knights and 2,000 infantry to defend the territory won in the Eastern Mediterranean. Only Tancred of the crusader princes remained with the aim of establishing his own lordship.[5] At this point the Franks held only Jerusalem and two great Syrian cities; Antioch and Edessa but not the surrounding country. Jerusalem remained economically sterile despite the advantages of being the centre of administration of church and state and benefitting from streams of pilgrims.[6]

Consolidation in the first half of the 12th-century established four Crusader states: the County of Edessa (1098–1149), the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268), the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291), and the County of Tripoli (1104–1289, although the city of Tripoli itself remained in Muslim control until 1109).[7] These states were the first examples of "Europe overseas". They are generally known as outremer, from the French outre-mer ("overseas" in English).[8][9]

Largely based in the ports of Acre and Tyre; Italian, Provencal and Spanish communes provided a significant characteristic of Crusader social stratification and political organisation. Separate from the Frankish nobles or burgesses, the communes were autonomous political entities closely linked to their countries of origin. This gave the inhabitants the ability to monopolise foreign trade and almost all banking and shipping in the Crusader states. Every opportunity to extend trade privileges was taken. One such example was the case of the Venetian Doge receiving one third of Tyre, its territories and exemption from all taxes after participating in the successful 1124 siege of the city. However, despite all efforts the two ports were unable to replace Alexandria and Constantinople as the primary centres of commerce in the region. [10] Instead, the communes competed with the Crown and each other to maintain economic advantage. Power derived from the support of the communards' native cities rather than their number, which never reached more than several hundred. Through this, by the middle of the 13th-century, the rulers of the communes were barely required to recognise the authority of the crusaders and divided Acre into a number of fortified miniature republics.[11]

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia had its origins before the Crusades, but was granted the status of a kingdom by Pope Innocent III, and later became fully westernized by the (French) Lusignan dynasty.

Kingdom of Cyprus

During the Third Crusade, the Crusaders founded the Kingdom of Cyprus. Richard I of England conquered Cyprus on his way to Holy Land. He subsequently sold the island to the Knights Templar who were unable to maintain their hold because of a lack of resources and a rapacious attitude towards the local population which led to a series of popular uprisings. The Templars promptly returned the island to Richard who resold it to the displaced King of Jerusalem Guy of Lusignan in 1192. Guy went on to found a dynasty that lasted until 1489, when the widow of James II The Bastard, Queen Catherine Cornaro, a native of Venice, abdicated her throne in favour of the Republic of Venice, which annexed the island.[12] For much of its history under the Lusignan Kings, Cyprus was a prosperous Medieval Kingdom, a commercial and trading hub of Western Christendom in the Middle East.[13] The Kingdom's decline began when it became embroiled in the dispute between the Italian Merchant Republics of Genoa and Venice. Indeed, the Kingdom's decline can be traced to a disastrous war with Genoa in 1373–74 which ended with the Genoese occupying the principal port City of Famagusta. Eventually with the help of Venice, the Kingdom recovered Famagusta but by then it was too late and in any event, the Venetians had their own designs on the island. Venetian rule over Cyprus lasted for just over 80 years until 1571, when the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Selim II Sarkhosh invaded and captured the entire island. The battle for Cyprus between Venice and the Ottoman Empire was immortalized by William Shakespeare in his play Othello, most of which is set in the port city of Famagusta on the eastern shores of the island.

Fourth Crusade

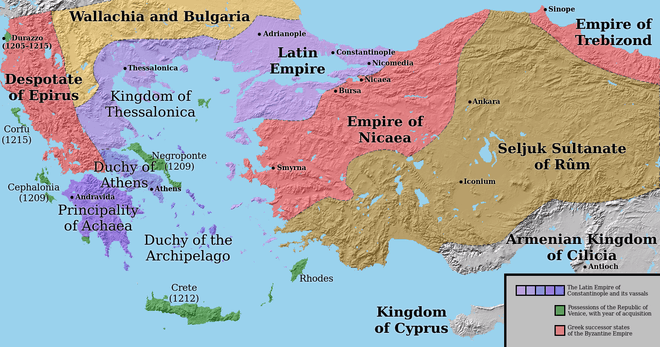

After the Fourth Crusade, the territories of the Byzantine Empire were divided into several states, beginning the so-called "Francocracy" (Greek: Φραγκοκρατία) period:

- The Latin Empire in Constantinople (1204–1261)

- The Kingdom of Thessalonica (1205–1224)

- The Principality of Achaea (1205–1432)

- The Lordship of Argos and Nauplia (1212–1388)

- The Duchy of Athens (1205–1458)

- The Margraviate of Bodonitsa (1204–1414)

- The Duchy of Naxos (1207–1579)

- The Duchy of Philippopolis (1204–1230)

Later history

Several islands, most notably Crete (1204–1669), Euboea (Negroponte, until 1470), and the Ionian Islands (until 1797) came under the rule of Venice.

These states faced the attacks of the Byzantine Greek successor states of Nicaea and Epirus, as well as Bulgaria. Thessalonica and the Latin Empire were reconquered by the Byzantine Greeks by 1261. Descendants of the Crusaders continued to rule in Athens and the Peloponnesus (Morea) until the 15th century when the area was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

- The military order of the Knights Hospitaller of Saint John established itself on Rhodes (and several other Aegean islands; see below) in 1310, with regular influx of new blood, until the Ottomans finally drove them out (to Malta) in 1522.

- The island of Kastellorizo (like Rhodes a part of the Aegean Dodecanese island group) was taken by the Knights of St. John Hospitaller of Jerusalem in 1309; the Egyptians occupied it from 1440 until 1450; then the Kingdom of Naples ruled till Ottoman conquest in 1512; Venetian rule began in 1659 (as Castellorosso); all these states, excluding the Egyptians, were Catholic; Ottoman rule was reestablished in 1660, although Greeks controlled the island during the Greek War of Independence from 1828–33.

- Other neighbouring territories temporarily under the order were: the cities of Smyrna (now İzmir; 1344–1402), Attaleia (now Antalya; 1361–1373 and Halicarnassos (now Bodrum;1402–1522), all three in Anatolia; the Greek Isthmus city of Corinth (1397–1404)), the city of Salona (ancient Amphissa; 1407–1410) and the islands of Ikaria (1424–1521) and Kos (1215–1522), all now in Greece.

Numismatics and sigillography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crusader seals. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coins of the Crusader states. |

The emblem used on the seals of the rulers of Jerusalem during the 12th century was a simplified depiction of the city itself, showing the tower of David between the Dome of the Rock and the Holy Sepulchre, surrounded by the city walls. The coins minted in Jerusalem during the 12th century show patriarchal crosses with various modifications. Coins minted under Henry I (r. 1192–1197) show a cross with four dots in the four quarters, but the Jerusalem cross proper appears only on a coin minted under John II (r. 1284/5).[14]

The crescent in pellet symbol is used in Crusader coins of the 12th century, in some cases duplicated in the four corners of a cross, as a variant of the cross-and-crosslets ("Jerusalem cross").[15] Many Crusader seals and coins show a crescent and a star (or blazing Sun) on either side of the ruler's head (as in the tradition of Sassanid coins), e.g. Bohemond III of Antioch, Richard I of England, Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse.[16] At the same time, the star in crescent is found on the obverse of Crusader coins, e.g. in coins of the County of Tripoli minted under Raymond II or III c. 1140s–1160s show an "eight-rayed star with pellets above crescent".[17]

Great Seal of Richard I of England (1198)[18]

Great Seal of Richard I of England (1198)[18] Equestrian seal of Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse with a star and a crescent (13th century)

Equestrian seal of Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse with a star and a crescent (13th century)

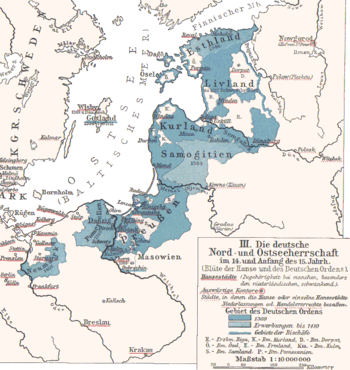

Northern Crusades

In the Baltic region, the indigenous tribes in the Middle Ages at first staunchly refused Christianity. In 1193, Pope Celestine III urged Christians to have a crusade against the heathens which included the Old Prussians, the Lithuanians and other tribes inhabiting Estonia, Latvia and East Prussia. This period of warfare is called the Northern Crusades.

In the aftermath of Northern Crusades William of Modena as Papal legate solved the disputes between the crusaders in Livonia and Prussia.

- By dividing the lands of the Terra Mariana between the crusading order of Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Church, five principalities were created:

- Archbishopric of Riga,

- Bishopric of Courland,

- Bishopric of Dorpat,

- Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek,

- The lands of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword.

- The Estonian lands controlled by Danish crusaders were annexed with Denmark as Duchy of Estonia[20] until it was ceded to the Teutonic Order state in 1346.

- In the Prussian region William of Modena divided the lands between Teutonic knights and the Church by creating four prince-bishoprics under the Archbishopric of Riga:

See also

- List of Crusader castles

- Map of the Crusader states from Muir's Historical Atlas (1911)

References

- ↑ Barber, Malcolm. “The Crusader States” (Yale University Press. 2012) ISBN 978-0-300-11312-9. Page xiii

- ↑ "Distinguishing the terms: Latins and Romans". Orbis Latinus.

- ↑ See for example The Crusader Kingdom of Valencia: Reconstruction on a Thirteenth-Century Frontier, R.I. Burns, SJ, Harvard, 1967 (available online)

- ↑ Barber, Malcolm. “The Crusader States” (Yale University Press, 2012) ISBN 978-0-300-11312-9. Page 110

- ↑ Asbridge 2012, p. 106

- ↑ Prawer 2001, p. 87

- ↑ Asbridge 2012, pp. 147–50

- ↑ "Outremer". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 50–51

- ↑ Prawer 2001, pp. 85-87

- ↑ Prawer 2001, pp. 87-93

- ↑ Edbury P.W., The Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades 1191 - 1374, Cambridge University Press (1991)

- ↑ Edbury P.W., The Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades 1191 - 1374, Cambridge University Press (1991)

- ↑ Hubert de Vries, Jerusalem (hubert-herald.nl). The design is also found on coins minted under his successor, the last king of Jerusalem, Henry II (forumancientcoins.com)

- ↑ In the 12th century found on pennies William the Lion (r. 1174–1195). William Till, An Essay on the Roman Denarius and English Silver Penny (1838), p. 73. E.g. "Rev: short cross with crescent and pellets in angles and +RAVLD[ ] legend for the moneyer Raul Derling at Berwick or Roxburgh mint" (timelineauctions.com). Seaby SE5025 "Rev. [+RAV]L ON ROC, short cross with crescents & pellets in quarters" (wildwinds.com).

- ↑ Bohemond III of Antioch (r. 1163–1201) "Obv. Helmeted head of king in chain-maille armor, crescent and star to sides" (ancientresource.com)

- ↑ "Billon denier, struck c. late 1140s-1164. + RA[M]VNDVS COMS, cross pattée, pellet in 1st and 2nd quarters / CIVI[TAS T]RIPOLIS, eight-rayed star with pellets above crescent. ref: CCS 6-8; Metcalf 509 (ancientresource.com).

- ↑ Richard is depicted as seated between a crescent and a "Sun full radiant" in his second Great Seal of 1198. English heraldic tradition of the early modern period associates the star and crescent design with Richard, with his victory over Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus in 1192, and with the arms of Portsmouth (Francis Wise A Letter to Dr Mead Concerning Some Antiquities in Berkshire, 1738, p. 18). Heraldic tradition also attributes a star-and-crescent badge to Richard (Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, 1909, p. 468).

- ↑ Found in the 19th century at the site of the Biais commandery, in Saint-Père-en-Retz, Loire-Atlantique, France, now in the Musée Dobré in Nantes, inv. no. 303. Philippe Josserand, "Les Templiers en Bretagne au Moyen Âge : mythes et réalités", Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l’Ouest 119.4 (2012), 7–33 (p.24).

- ↑ High medieval rural settlement in Scandinavia; The Cambridge History of Scandinavia By Knut Helle; p. 269 ISBN 0-521-47299-7

Bibliography

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

- Prawer, Joshua (2001). The CRusaders' Kingdom. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-224-X.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). The Crusades: A Short History (Second ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10128-7.

- Barber, Malcolm. “The Crusader States” (Yale University Press, 2012)

- Burns, R.I. The Crusader Kingdom of Valencia: Reconstruction on a Thirteenth-Century Frontier (1967)

- Edbury P.W. The Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades 1191 - 1374 (Cambridge University Press, 1991)

- Konstam, Angus (2002). Historical Atlas of The Crusades. New York: Thalamus. p. 192. ISBN 0-8160-4919-X.

- Jotischky, Andrew. Crusading and the crusader states (Routledge, 2014)

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes. Byzantium and the Crusader States, 1096-1204 (Oxford University Press, 1993)

- Runciman, Steven. "The Crusader States, 1243-1291." in Kenneth M. Setton, ed. A History of the Crusades (1969) 2: 1189-1311.

Primary sources

- Burns, Robert Ignatius. Diplomatarium of the Crusader Kingdom of Valencia: Documents 1-500: Foundations of crusader Valencia, revolt and recovery, 1257-1263. Vol. 2. (Princeton University Press, 2007)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crusader states. |