Az-Zakariyya

| az-Zakariyya | |

|---|---|

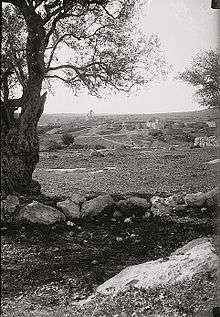

Az-Zakariyya, pre-1926 | |

az-Zakariyya | |

| Arabic | زكرية |

| Name meaning | "Zachariah" |

| Also spelled | al-Zakariya |

| Subdistrict | Hebron |

| Coordinates | 31°42′30″N 34°56′50″E / 31.70833°N 34.94722°ECoordinates: 31°42′30″N 34°56′50″E / 31.70833°N 34.94722°E |

| Palestine grid | 145/124 |

| Population | 1,180[1] (1945) |

| Area |

15,320[1] dunams 15.3 km² |

| Date of depopulation | June, 1950[2] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Expulsion by Yishuv forces |

| Current localities | Zekharia[3] |

Az-Zakariyya or Zakaria (Arabic: زكرية[4]) was a Palestinian Arab village 25 km northwest from the city of Hebron (al-Khalil) in the Hebron Subdistrict, which was depopulated in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The village had a population of 1,180 on 15,320 dunums in 1945. The village was named in honor of the prophet Zachariah. In 1950, the Israeli moshav of Zekharia was founded on the site of Az-Zakariyya.

Location

The village lay beside a Tell by the same name.[5][6] The Tell rests upon a high hilltop, whereas the village lay on a slightly elevated part of the valley below, on the northwest side of the hill.[7] The hill rises to a maximum elevation of 372 meters above sea level,[8] with a mean elevation of approximately 275 meters above sea level.[9] The village lay next to the road between Bayt Jibrin and the Jerusalem-Jaffa highway. The streams of Wadi Ajjur and al-Sarara were located a few kilometers north of the village.[9]

History

A tomb, dating from the early Iron Age, have been excavated here. Among the pottery found in the grave was a figurine, representing Astarte.[10]

A town called Beit Zacharia (var. Kefar Zacharia) existed on the hill in Roman times,[11] from whence the village takes its name. According to Sozomen, the body of the prophet Zachariah was found here in 415 C.E. and a church and monastery were established.[12][13][14] The village was under the administrative jurisdiction of Bayt Jibrin. During the Mamluk era, the village was a dependency of Hebron, and formed part of the waqf supporting the Ibrahimi Mosque.[15]

In the 1480s C.E. Felix Fabri described how he stayed in a "roomy inn", next to a "fair mosque" in the village.[16]

Ottoman era

In 1517, Az-Zakariyya was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the rest of Palestine, and in 1596 the village appeared in the Ottoman tax registers listed as Zakariyya al-Battikh under the administration of the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Quds (Jerusalem), part of the Sanjak of Quds. It had a population of 47 Muslim households and paid taxes on wheat, barley, olives, beehives, and goats.[17]

A Maqam (shrine) in the village dedicated to the prophet Zechariah was noticed by Edward Robinson in 1838.[18] A Dutch traveler to Palestine in the 19th century records its name as Kefr Zakaria.[7]

In 1863 the French explorer Victor Guérin found the place to have five hundred inhabitants,[19] while an Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed that Az-Zakariyya had 41 houses and a population of 128, though the population count included men only.[20][21]

In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Zakariyya as sitting on a slope above a broad valley surrounded by olive groves.[22]

In 1896 the population of (Tell) Zakarja was estimated to be about 636 persons.[23]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Zakaria had a population of 683, all Muslim,[24] increasing in the 1931 census to 742, still all Muslims, in 189 occupied houses.[25]

By 1945, the population was 1,180, all Muslims,[26] with a total of 15,320 dunams of land.[1] In 1944/45 a total of 6,523 dunums of village land was allocated to cereals, 961 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards, of which 440 dunums were planted with olive trees,[27][28] while 70 dunams were built-up (urban) areas.[29] In the 1946 Tax Form of Mandatory Palestine, there were 357 "assessable inhabitants" living in Zakariyya, of which 232 were landowners.[30]

1948 and aftermath

In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Az-Zakariyya was the longest lasting Arab community in the southern Jerusalem Corridor.[31] The village was defended by the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, the Arab Liberation Army and local militiamen, who were defeated by the Israel Defense Forces on October 23, 1948. In the course of Operation Yoav, the 54th Battalion of the Givati Brigade, found the village "almost empty", as most of the residents had fled to the nearby hills. Two residents were executed by Israeli soldiers.[31] In December 1948 the army evicted about 40 "old men and women" to the West Bank.[32] In March 1949 the Interior Ministry requested the eviction of "145 or so" remaining villagers: the official in charge of the Jerusalem District said there were many good houses in the village which could be used to accommodate several hundred new immigrants.[33] In January 1950 David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Sharett and Yosef Weitz decided to evict the villagers, "but without coercion."[34] On March 19, 1950 the transfer of the Arabs of Zakariya was approved and the order was carried out on June 9, 1950.[35]

The manner of expulsion of the villagers is not mentioned.[3] Some of the villagers moved to Ramla and Lod while others ("perhaps the majority") settled in the Dheisheh Refugee Camp in the West Bank.[35]

Following the war, the area was incorporated into the State of Israel. In 1950 the moshav of Zekharia was established on the village land, close to the village site.[3]

During the 1960s, most of the buildings in the village were destroyed as part of a national program to "level" depopulated villages.[36]

In 1992, Walid Khalidi described the remaining structures: "The mosque and a number of houses, some occupied by Jewish residents and others deserted, remain on the site. Large sections of the site itself are covered with wild vegetation. The mosque is in a state of neglect and an Israeli flag is planted on top of the minaret. [..] One of the occupied houses is a two-storey stone structure with a flat roof. Its second story windows have round arches and grillwork. Parts of the surrounding lands are cultivated by Israeli farmers."[3]

Culture

The village was known for its Palestinian costumes. A wedding dress from Zakariyya (ca. 1930) is part of the collection in Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) at Museum of New Mexico at Santa Fe.[37]

Notable residents

References

- 1 2 3 Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 50 Archived 2009-07-20 at WebCite

- ↑ Morris, 2004, p. xix, village # 295. Also gives the cause for depopulation

- 1 2 3 4 Khalidi, 1992, p. 226

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 338

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, vol. II, section XI, London 1856, pp. 16, 21

- ↑ Guérin, 1869, pp. 316–319

- 1 2 van de Velde, 1858, p.115

- ↑ Tel Azekah

- 1 2 Khalidi, 1992, pp. 224-225

- ↑ Baramki, 1935, pp. 109-110

- ↑ Azekah via Bible Walks.com

- ↑ Sozomen, 1855, pp. 423-424

- ↑ Pringle, 1993, p. 204

- ↑ Petersen, 2001, p. 320

- ↑ Mujir al-Din, 1876, pp. 230-1. Cited and translated in Petersen, 2001, p. 320

- ↑ Fabri, 1893, p. 427

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 120

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 343, 344

- ↑ Guérin, 1869, p. 371

- ↑ Socin, 1879, p. 163

- ↑ Hartmann, 1883, p. 145, noted 56 houses

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 27. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 225

- ↑ Schick, 1896, p. 123

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Hebron, p. 10

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 34

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 23

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 94

- ↑ Khalidi, 1992, p. 225

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 144

- ↑ Zakariya - Assessments & calculations, June 1946

- 1 2 Morris, 2004, p. 521

- ↑ Fourth Brigade \Intelligence, "Daily Summary 18.12.48, 19. Dec. 1948, IDFA 6647\49\\48. Quoted in Morris, 2004, p. 521

- ↑ A. Bergman, cited in Morris, 2004, p. 521

- ↑ Entry for 14 Jan. 1950, Weitz, Diary, IV, p. 69. Cited in Morris, 2004, p. 521

- 1 2 Mordechai Bar-On, officer in charge of the eviction. Quoted in Morris, 2004, p. 521

- ↑ Arnon Shai (2006). "The Fate of Abandoned Arab Villages in Israel, 1965-1969". History and Memory. 18 (2): 86–106.

- ↑ Stillman, 1979, p. 60.

Bibliography

- Al Jundi, Sami; Marlowe, Jen (2011). Hour of Sunlight. Nation Books. ISBN 978-1-56858-631-1. Zakariyya: pp. 1–17

- Baramki, D. C. (1935). "An early Iron Age Tomb at Ez Zahiriyye". Quarterly Of The Department Of Antiquities In Palestine. 4: 109–110.

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Fabri, Felix (1893). Felix Fabri (circa 1480–1483 A.D.) vol II, part II. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, Sami (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, Walid (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Moudjir ed-dyn al-'Ulaymi (1876). Sauvaire, ed. Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. : fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 39036 2.

- Robinson, Edward; Smith, Eli (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Sozomen (1855). The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen: Comprising a History of the Church from A.D. 324 to A.D. 440. Henry G. Bohn.

- Stillman, Yedida Kalfon (1979). Palestinian Costume and Jewelry. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0490-7. (A catalog of the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) at Santa Fe's collection of Palestinian clothing and jewellery.)

- van de Velde, Carel Willem Meredith (1858). Memoir to Accompany the Map of the Holy Land. Gotha: Justus Perthes.

External links

- Welcome to Zakariyya

- Zakariyya, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons