Grimes County, Texas

| Grimes County, Texas | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The Grimes County Courthouse in Anderson | |

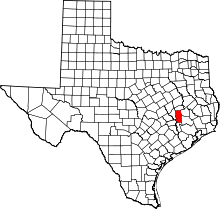

Location in the U.S. state of Texas | |

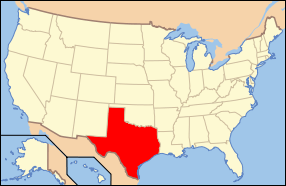

Texas's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | 1846 |

| Named for | Jesse Grimes |

| Seat | Anderson |

| Largest city | Navasota |

| Area | |

| • Total | 802 sq mi (2,077 km2) |

| • Land | 787 sq mi (2,038 km2) |

| • Water | 14 sq mi (36 km2), 1.8% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 26,604 |

| • Density | 34/sq mi (13/km2) |

| Congressional district | 8th |

| Time zone | Central: UTC−6/−5 |

| Website |

www |

Grimes County is a county located in southeastern Texas in the United States. As of the 2010 census, its population was 26,604.[1] The seat of the county is Anderson.[2] The county was formed from Montgomery County in 1846.[3] It is named for Jesse Grimes, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence and early European-American settler of the county.[4]

The Navasota and Brazos rivers form the western boundary of the county. The Trinity River is located to the north, and eastern areas are part of the watershed of the San Jacinto River.

History

In the historic period, French and Spanish explorers encountered the Bidai Indians, who were mentioned in Spanish records from 1691. Like other tribes, they suffered high fatalities from new infectious diseases and joined with the remnants of other Native American people later in the historic period.

This area was generally not settled by Europeans and creole Spanish for nearly a century, during Spanish colonial rule. After Mexico achieved independence, it accepted settlers from the United States into eastern Texas. It allowed them to practice their own religion, if they swore loyalty to Mexico.

A few structures in Anderson date from this period, as well as from the Texas Republic and early statehood eras. Because of the wealth of structures reflecting this extended historic period, the town and nearby area are designated as the "Anderson Historic District", which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Anglo-American migration to what became Grime County began in the 1820s, when it was part of Mexico. Early settlers were primarily from the South, especially Alabama, and most brought enslaved African Americans with them, whom they relied on for labor. The first cotton gin in Texas was built by Jared E. Groce, who had settled with 90 slaves near what is now Hempstead, Texas, developing a cotton plantation.[5]

Texas achieved independence in 1836 and settlers continued to arrive from the United States. Much of the fertile lowlands were initially developed for cotton plantations, especially in the late antebellum period.[5]

Grimes County was organized in 1846, a year after the Republic of Texas agreed to annexation by the United States and became a state. From 1850 to the Civil War the white population increased markedly but, as settlers from the South continued to bring in numerous slaves, the black population increased even faster. Planters continued to grow cotton and corn as commodity crops. By 1860 there were 4,852 whites in the county and 5,468 slaves, who made up 53 percent of the population. The white population had doubled in the preceding decade, and the slave population had tripled. Grimes had a total of 505 slaveholders in 1860, with 77 holding 20 slaves or more, the qualification for being considered major planters. It one of 17 (seventeen) counties in the state where slaveholders held on average, more than 10 slaves each.[5]

In such conditions, whites were anxious after the emancipation of slaves, and also struggled with adapting to a free labor market. White violence rose after the war, and the Ku Klux Klan established a local chapter in 1868 to assert dominance. Federal troops were stationed in the area and the Freedman's Bureau had an office in the county. They were not successful in protecting freedmen, but the Bureau established schools in [5]

Determined to crush populist efforts and alliances with Republicans that resulted in victories in 1896 and 1898, white Democrats formed what became the White Man's Union, a secret, oath-bound organization that violently took over elections in 1900, after killing several black Populist leaders. It selected all county officials until 1958.[5]

White violence continued after Reconstruction and into the early 20th century, when whites committed 9 lynchings of blacks in the county, part of racial terrorism to suppress the freedmen. Grimes and Freestone counties had the same number of lynchings in this period, ranking as the fifth-highest totals in a state where lynchings were widespread and conducted in many counties.[6] The economy declined in the late 19th century, increasing social tensions.

In 1859 the Houston and Texas Central extended its line into the county. Anderson, the county seat, rejected it and was bypassed for Navasota, which soon surpassed it in size.[5] Anderson finally got a railroad in the early 1900s, but never caught up with Navasota. In the late 19th and 20th centuries, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe and the Union Pacific became the major railroads in the county.

In response to the violence and takeover by the White Man's Union, African Americans began to leave the county in large number. The population of the county declined markedly from 1900 to 1920, and after 1930 to 1980. These were periods of the Great Migration, as African Americans left Texas and other parts of the South to leave behind the oppression of Jim Crow and disenfranchisement, and seek better work. From 1940 on, many migrated to the West Coast for jobs in the expanding defense industry. Rural whites also left the South for industrial cities.

The county remained mostly rural and agricultural until the late 20th century, which contributed to its continuing population losses. Timber harvesting and processing were part of early industry in the 20th century. But stock raising and dairy farms contributed more to the overall agricultural economy in the later 20th century,, making up 93% of its revenues. In addition, crops have become more diversified.[5] Railroad restructuring in the late 20th century resulted in mergers among some lines. In the 21st century, State Highway 90 is the major north-south thoroughfare, and State highways 30 and 105 run east and west. With some new manufacturing, population began to increase since the late 1970s. In 2014 the census estimated 27,172 people living in Grimes County. About 59.5 percent were Anglo, 22.6 percent were Hispanic, and 16.5 percent were African American.[5]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 802 square miles (2,080 km2), of which 787 square miles (2,040 km2) is land and 14 square miles (36 km2) (1.8%) is water.[7]

Major highways

Adjacent counties

- Madison County (north)

- Walker County (northeast)

- Montgomery County (southeast)

- Waller County (south)

- Washington County (southwest)

- Brazos County (west)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 4,008 | — | |

| 1860 | 10,307 | 157.2% | |

| 1870 | 13,218 | 28.2% | |

| 1880 | 18,603 | 40.7% | |

| 1890 | 21,312 | 14.6% | |

| 1900 | 26,106 | 22.5% | |

| 1910 | 21,205 | −18.8% | |

| 1920 | 23,101 | 8.9% | |

| 1930 | 22,642 | −2.0% | |

| 1940 | 21,960 | −3.0% | |

| 1950 | 15,135 | −31.1% | |

| 1960 | 12,709 | −16.0% | |

| 1970 | 11,855 | −6.7% | |

| 1980 | 13,580 | 14.6% | |

| 1990 | 18,828 | 38.6% | |

| 2000 | 23,552 | 25.1% | |

| 2010 | 26,604 | 13.0% | |

| Est. 2016 | 27,671 | [8] | 4.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] 1850–2010[10] 2010–2014[1] | |||

As of the 2000 Census,[11] there were 23,552 people, 7,753 households, and 5,628 families residing in the county. The population density was 30 people per square mile (11/km²). There were 9,490 housing units at an average density of 12 per square mile (5/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 71.79% White, 19.96% Black or African American, 0.32% Native American, 0.30% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 5.93% from other races, and 1.65% from two or more races. 16.08% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

Christianity is the primary religion in the county and Hinduism is the second.[12]

There were 7,753 households out of which 34.60% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.40% were married couples living together, 12.60% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.40% were non-families. 23.80% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.69 and the average family size was 3.18.

In the county, the population was spread out with 24.80% under the age of 18, 7.70% from 18 to 24, 29.80% from 25 to 44, 24.00% from 45 to 64, and 13.70% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females there were 117.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 124.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $32,280, and the median income for a family was $38,008. Males had a median income of $30,138 versus $21,747 for females. The per capita income for the county was $14,368. About 13.80% of families and 16.60% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.40% of those under age 18 and 18.10% of those age 65 or over.

Government and infrastructure

Given the black majority in the county, after the Civil War the Republican Party gained offices here.

As is the case in most of Texas, during the late 20th century conservative whites shifted from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party. As they comprise the majority of residents, they have voted largely for Republican presidential candidates since 1968, as is shown by the table below.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 74.1% 7,065 | 23.0% 2,194 | 2.9% 274 |

| 2012 | 71.4% 6,141 | 27.2% 2,339 | 1.4% 121 |

| 2008 | 66.8% 5,562 | 32.5% 2,704 | 0.7% 56 |

| 2004 | 65.5% 5,263 | 33.8% 2,713 | 0.7% 54 |

| 2000 | 61.7% 4,197 | 36.0% 2,450 | 2.3% 155 |

| 1996 | 45.0% 2,564 | 45.3% 2,584 | 9.7% 553 |

| 1992 | 38.6% 2,402 | 41.7% 2,594 | 19.6% 1,221 |

| 1988 | 50.5% 2,820 | 49.0% 2,735 | 0.5% 27 |

| 1984 | 58.5% 3,365 | 41.2% 2,370 | 0.3% 17 |

| 1980 | 45.4% 2,087 | 53.0% 2,440 | 1.6% 75 |

| 1976 | 35.5% 1,473 | 64.0% 2,656 | 0.5% 19 |

| 1972 | 66.4% 2,243 | 33.1% 1,116 | 0.5% 17 |

| 1968 | 30.5% 1,076 | 41.8% 1,473 | 27.7% 976 |

| 1964 | 31.2% 1,014 | 68.7% 2,229 | 0.1% 4 |

| 1960 | 37.9% 1,053 | 61.7% 1,713 | 0.4% 12 |

| 1956 | 54.0% 1,281 | 45.5% 1,079 | 0.6% 14 |

| 1952 | 53.3% 1,557 | 46.6% 1,362 | 0.0% 1 |

| 1948 | 19.5% 336 | 52.4% 901 | 28.1% 483 |

| 1944 | 7.0% 137 | 79.1% 1,559 | 13.9% 274 |

| 1940 | 9.3% 298 | 90.6% 2,899 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1936 | 6.8% 136 | 93.1% 1,851 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1932 | 6.9% 153 | 92.9% 2,065 | 0.2% 5 |

| 1928 | 37.4% 701 | 62.6% 1,175 | |

| 1924 | 7.6% 177 | 91.1% 2,136 | 1.4% 32 |

| 1920 | 14.8% 214 | 70.9% 1,027 | 14.4% 208 |

| 1916 | 8.7% 108 | 89.1% 1,108 | 2.2% 27 |

| 1912 | 3.3% 35 | 89.5% 941 | 7.2% 76 |

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) operates the O.L. Luther Unit and the Wallace Pack Unit in an unincorporated area in Grimes County.[14] In addition the Pack Warehouse is located in an unincorporated area near the Pack Unit.[15]

Communities

Cities

- Anderson (county seat)

- Bedias

- Iola

- Navasota

- Todd Mission

Unincorporated communities

Notable residents

- Actor Chuck Norris lives in Navasota, the county's largest city, where he and his wife opened a bottled water production facility. He starred in the television series Walker, Texas Ranger. [16]

See also

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Grimes County". The Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ "Grimes County - Named After Jesse Grimes". Stopping Points Historical Markers & Points of Interest. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Grimes County from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ Lynching in America/Summary by County (3rd edition), p. 9, Equal Justice Initiative, 2017, Montgomery, Alabama

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Texas Almanac: Population History of Counties from 1850–2010" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ Wilson, Reid. The second-largest religion in each state, Washington Post, June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ "Pack Unit Archived 2010-07-25 at the Wayback Machine.." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Pack Warehouse Archived 2010-07-12 at the Wayback Machine.." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Chuck Norris and wife open new bottled water production facility in Navasota". KBTX-TV. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

External links

- Grimes County government's website

- Grimes County from the Handbook of Texas Online