Brownsville, Texas

| Brownsville, Texas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| City of Brownsville | |||

Top to bottom, left to right: Cameron County Courthouse, Reynaldo G. Garza & Filemon B. Vela Federal Courthouse, Wells Fargo Bank, Brownsville Ship Channel, La Plaza at Brownsville Terminal Center, Arts Center at Texas Southmost College, United States Court House, Custom House, and Post Office, Villa del Sol Building, Market Square at Downtown Brownsville, Hotel El Jardin (now defunct) and Lone Star National Bank. | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): "The Green City" | |||

| Motto(s): "On the Border, By the Sea!" | |||

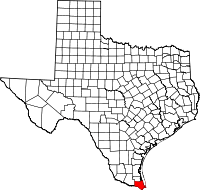

Location in Cameron County | |||

Brownsville Location in the contiguous United States | |||

| Coordinates: 25°55′49″N 97°29′4″W / 25.93028°N 97.48444°WCoordinates: 25°55′49″N 97°29′4″W / 25.93028°N 97.48444°W | |||

| Country | United States of America | ||

| State | Texas | ||

| County | Cameron | ||

| Metropolitan area | Brownsville-Harlingen Metropolitan Area | ||

| Settled | 1848 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Council-Manager | ||

| • City Council |

Mayor: Antonio "Tony" Martinez Commissioner At-Large "A": Cesar de Leon Commissioner At-Large "B": Rose M. Z. Gowen Commissioner District 1: Ricardo Longoria, Jr. Commissioner District 2: Jessica Tetreau-Kalifa Commissioner District 3: Joel Munguia Commissioner District 4: Ben Neece | ||

| • City manager | Michael Lopez (Interim) | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 146.3 sq mi (378.9 km2) | ||

| • Land | 132.3 sq mi (342.7 km2) | ||

| • Water | 13.9 sq mi (36.1 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 33 ft (10 m) | ||

| Population (2018 estimate) | |||

| • City | 189,592 (US: 131st) | ||

| • Density | 1,383/sq mi (534.1/km2) | ||

| • Metro | 420,392 (US: 126th) | ||

| • Metro density | 1,602.2/sq mi (615.9/km2) | ||

| • Demonym | Brownsvillian | ||

| • CSA | 444,059 (US: 93rd) | ||

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) | ||

| ZIP Codes | 78520, 78521, 78522, 78523, 78526 | ||

| Area code(s) | 956 | ||

| FIPS code | 48-10768[1] | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1372749[2] | ||

| Airport | Brownsville/South Padre Island International Airport KBRO (BRO) | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Brownsville is the county seat of Cameron County, Texas, United States. It is the sixteenth-most populous city in the state of Texas, with a population at the 2010 census of 175,023[3] and an estimated population of 189,592 as of 2018.[4] Brownsville is located at the southernmost tip of Texas, on the northern bank of the Rio Grande, directly north and across the border from Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico.

The 2014 U.S. Census Bureau estimate placed the Brownsville–Harlingen metropolitan area population at 420,392, making it the ninth most populous metropolitan area in the state of Texas.[5] In addition, the international Matamoros–Brownsville Metropolitan Area was estimated to have a population of 1,136,995.[6]

Brownsville has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation, and is frequently cited as having the highest percentage of residents in the nation below the federal poverty level.[7] However, the urban area is also one of the fastest growing in the United States.[8] The city's population dramatically increased after a boom in the steel industry during the first decade of the 1900s, when steel output tripled. In the early 21st century, the Port of Brownsville has become a major economic hub for South Texas, where shipments arrive from other parts of the United States, from Mexico, and from around the world.[9]

Brownsville's economy is based mainly on its international trade with Mexico through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). It is home to one of the fastest growing manufacturing sectors in the nation.[10] Brownsville has been recognized as having one of the best pro-business climates in the United States,[11] and the city has been ranked among the least expensive places to live in the U.S.[12]

Brownsville served as a site for several battles and events in the Texas Revolution,[13] the Mexican–American War,[14] and the American Civil War.[15] Just across the U.S–Mexico border lies Matamoros, Tamaulipas, a city with a population of 500,000 people. It was a major site of the Mexican War of Independence,[16] the Mexican Revolution,[17] and the French Intervention.[18] It also is a major manufacturing center.

History

In April 1846, construction of a fort on the Mexican border was begun by American forces due to increased instability in the region on the eve of the Mexican–American War of 1846–1848.[19] Before the completion of the construction, the Mexican Army began the Siege of Fort Texas, during the first active campaign in the Mexican–American War, from May 3–9, 1846. The first battle of the war occurred on May 8, when General Zachary Taylor received word of the siege of the fort. Taylor's forces rushed to help, but Mexican troops intercepted them, resulting in the Battle of Palo Alto, approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) north of present-day Brownsville.

The next morning the Mexican forces had retreated, and Taylor's troops caught up with them, resulting in the Battle of Resaca de la Palma, which took place within the present city limits. When Taylor finally arrived at the besieged Fort Texas, he found that two soldiers had died, including the fort's commander, Major Jacob Brown. In his honor, General Taylor renamed the facility as Fort Brown. An old cannon at the University of Texas at Brownsville and Texas Southmost College marks the spot where Major Brown received his fatal wound.

It should be noted that Ulysses S. Grant was a young second lieutenant at this battle. Two future U.S. presidents served at this battle.

The city of Brownsville was originally established late in 1848 by Charles Stillman, and was made the county seat of the new Cameron County on January 13, 1849. The state originally incorporated the city on January 24, 1850. This was repealed on April 1, 1852, due to a land-ownership dispute between Stillman and the former owners. The state reincorporated the city on February 7, 1853, which remains in effect. The issue of ownership was not decided until 1879, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Stillman.

On July 13, 1859, the First Cortina War started. Juan Nepomuceno Cortina became one of the most important historical figures of the area, and continued to exert a decisive influence in the local events until his arrest in 1875. The First Cortina War ended on December 27, 1859. In May 1861, the brief Second Cortina War took place.

During the American Civil War, Brownsville served as a smuggling point for Confederate goods into Mexico, most importantly cotton smuggled to European ships waiting at the Mexican port of Bagdad. Initially the Confederates controlled Fort Brown. In November 1863, Union troops landed at Port Isabel and marched for Brownsville to stop the smuggling. In the ensuing battle of Brownsville, Confederate forces abandoned the fort, blowing it up with 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) of explosives. In 1864, Confederate forces commanded by John Salmon 'Rip' Ford reoccupied the town.

On May 15, 1865, a month after the surrender had been signed at Appomattox Court House, the Battle of Palmito Ranch (accepted by some criteria as the war's last battle) was fought and won by the Confederates. As President, Ulysses S. Grant sent Union General Frederick Steele to Brownsville to patrol the Mexican–American border after the Civil War to aid the Juaristas with military supplies.

20th century to present

Like other Southern states, Texas passed a new constitution and Jim Crow laws that established racial segregation and disenfranchised African Americans at the turn of the 20th century, generally by raising barriers to voter registration. While Hispanic residents were considered white under the terms of the US annexation of Texas, the white-dominated legislature still found ways to suppress their participation in politics.

On August 13 and 14, 1906, Brownsville was the site of the Brownsville Affair. Racial tensions were high between white townsfolk and black infantrymen who were stationed at Fort Brown. On the night of August 13, one white bartender was killed and a white police officer was wounded by rifle shots in the street. Townsfolk, including the mayor, accused the infantrymen of the murders. Without affording them a chance to defend themselves in a hearing, President Theodore Roosevelt dishonorably discharged the entire 167-member regiment due to their alleged "conspiracy of silence". Further investigations in the 1970s found that the soldiers were not at fault, and the Nixon Administration reversed all dishonorable discharges. Only two men of the unit were still alive.

On September 8, 1926, The Junior College of the Lower Rio Grande Valley (later known as Texas Southmost College) admitted its first class. In 1945, Fort Brown was decommissioned after the end of World War II. In 1948 the City and College acquired the land. Between 1945 and 1970, Brownsville's population continued to grow, more than doubling from 25,000 to 52,000 people. In 1991, Brownsville received a university via the partnership with the University of Texas at Brownsville.

The city of Brownsville was the center of a controversy surrounding the Trump administration policy of separating children and parents who entered the country unlawfully. The controversy surrounded Casa Padre, the largest juvenile immigration detention center in America which is located in town.[20]

Geography

Brownsville is located on the U.S.–Mexico border (marked here by the Rio Grande) opposite Matamoros, Tamaulipas. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 146.3 square miles (378.9 km2), making it the largest American city by land area in the lower Rio Grande Valley. It is the third-largest American city by land area along the U.S.-Mexico border, after San Diego, California and El Paso, Texas. A total of 132.3 square miles (342.7 km2) of Brownsville's area is land, and 13.9 square miles (36.1 km2) is water.[3]

Brownsville is among the southernmost of all contiguous U.S. cities. Within the contiguous United States, only a handful of municipalities in Florida's Miami-Dade and Monroe counties (plus Everglades City in Collier County) are located further south than Brownsville. It lies at exactly the same latitude as North Miami Beach in northern Miami-Dade County.

In its efforts to become a cleaner, greener city, Brownsville became one of the first cities in the U.S. and Texas to require stores to charge a fee for single-use plastic shopping bags. In the first five years of the program, approximately $3.8 million was collected. Funds have been used for city beautification and maintenance projects.[21] These results have led other cities in the area to also consider such a fee. Forbes has identified Brownsville as one of 12 metropolitan areas in the U.S. with the cleanest air; Laredo was the only other Texas metropolitan area to be among the 12.[22]

Flora

Broadleaf evergreen plants, including palms, dominate Brownsville neighborhoods to a greater degree than is seen elsewhere in Texas—even in nearby cities such as Harlingen and McAllen. Soils are mostly of clay to silty clay loam texture, moderately alkaline (pH 8.2) to strongly alkaline (pH8.5) and with a significant degree of salinity in many places.[23]

Climate

| Brownsville | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Brownsville has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa),[24] inland is a transition zone just outside a hot semi-arid climate, closer to the coast is a transition zone to tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw) The nearby ocean waters and winds from the Gulf of Mexico help keep Brownsville cooler during the summer relative to cities further inland, such as Laredo and McAllen. Temperatures above 100 °F (37.8 °C) are uncommon, with an average of only 1.1 days reaching that level of heat. At the other extreme, there is an average of one to two nights per year with freezing temperatures.[25] Average monthly rainfall demonstrates a strong September maximum; the next-wettest month is October, with a slight May–June peak across the rest of the year. Generally, November through April represents a marked drier season, and Brownsville can go for weeks with minimal, even negligible, rainfall, especially during the cooler season. Despite this, Brownsville's rain totals fluctuate and the city has had several years of above-average precipitation from time to time. Extreme temperatures range from 12 °F (−11 °C) on February 13, 1899 to 106 °F (41 °C) on March 27, 1984. The greatest snowfall in a day and a season was 1.5 inches (3.8 cm), which fell on December 25, 2004.[25] The coolest month is January and the warmest month is August.[26]

Brownsville's proximity to the Gulf Coast means it is in the path of hurricanes. Throughout its history, the area has been affected by several major hurricanes, most notably the 1933 Cuba-Brownsville hurricane, Beulah, Allen, Bret and Dolly. The area is more likely to be affected by weak cyclones, tropical storms, and depressions. Since 2010, the city has seen an increase in the number and damage of tropical storms, believed to be caused by the El Niño phenomenon.

On December 25, 2004, Brownsville had its first instance of measurable snow in 109 years,[27] with 1.5 inches (3.8 cm), and the first recorded White Christmas. This was part of the 2004 Christmas Eve Snowstorm.[28]

Because it is located at the intersection of different climate regimes (subtropical, Chihuahuan desert, Gulf Coast plain, and Great Plains), it is a prime birding area. Its unique network of resacas (distributaries of the Rio Grande and oxbow lakes) provide habitat for numerous nesting/breeding birds of various types – most notably during the spring and fall migrations.

| Climate data for Brownsville, Texas (1981−2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1878−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 95 (35) |

94 (34) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

99 (37) |

98 (37) |

94 (34) |

106 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 70.6 (21.4) |

73.7 (23.2) |

78.9 (26.1) |

83.7 (28.7) |

88.4 (31.3) |

92.1 (33.4) |

93.6 (34.2) |

94.4 (34.7) |

90.5 (32.5) |

85.7 (29.8) |

79.1 (26.2) |

71.8 (22.1) |

83.5 (28.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 51.6 (10.9) |

54.7 (12.6) |

59.6 (15.3) |

65.9 (18.8) |

72.3 (22.4) |

75.7 (24.3) |

76.3 (24.6) |

76.2 (24.6) |

73.1 (22.8) |

66.9 (19.4) |

59.6 (15.3) |

52.7 (11.5) |

65.4 (18.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 18 (−8) |

12 (−11) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

41 (5) |

56 (13) |

58 (14) |

63 (17) |

51 (11) |

35 (2) |

27 (−3) |

16 (−9) |

12 (−11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.27 (32.3) |

1.08 (27.4) |

1.23 (31.2) |

1.54 (39.1) |

2.64 (67.1) |

2.57 (65.3) |

2.04 (51.8) |

2.44 (62) |

5.92 (150.4) |

3.74 (95) |

1.82 (46.2) |

1.15 (29.2) |

27.44 (697) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.3 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 6.6 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 74.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79.3 | 77.4 | 74.6 | 75.1 | 76.5 | 75.0 | 73.2 | 73.8 | 76.3 | 75.3 | 76.1 | 78.2 | 75.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 130.6 | 151.3 | 206.8 | 232.7 | 266.4 | 306.5 | 334.4 | 306.4 | 252.0 | 228.3 | 166.2 | 130.7 | 2,712.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 39 | 48 | 56 | 61 | 64 | 74 | 79 | 76 | 68 | 64 | 51 | 40 | 61 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[25][29][30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,734 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,734 | 0.0% | |

| 1870 | 4,905 | 79.4% | |

| 1880 | 4,938 | 0.7% | |

| 1890 | 6,134 | 24.2% | |

| 1900 | 6,305 | 2.8% | |

| 1910 | 10,517 | 66.8% | |

| 1920 | 11,791 | 12.1% | |

| 1930 | 22,021 | 86.8% | |

| 1940 | 22,083 | 0.3% | |

| 1950 | 35,086 | 58.9% | |

| 1960 | 48,040 | 36.9% | |

| 1970 | 52,522 | 9.3% | |

| 1980 | 84,997 | 61.8% | |

| 1990 | 98,962 | 16.4% | |

| 2000 | 139,722 | 41.2% | |

| 2010 | 175,023 | 25.3% | |

| Est. 2016 | 183,823 | [31] | 5.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

As of the census[1] of 2010, there were 175,023 people, 49,871 households, and 41,047 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,207.1 people per square mile (466.0/km2). There were 53,936 housing units at an average density of 372.0 per square mile (143.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was:

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race) – 91.28%

- Mexican – 73.93%

- Puerto Rican – 0.15%

- Cuban - 0.11%

- Other Hispanic or Latino – 17.08%

- Not Hispanic or Latino – 8.72%

- White alone - 7.75%[32]

There were 38,174 households out of which 50.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.3% were married couples living together, 20.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 15.7% were non-families. 13.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.62 and the average family size was 3.99.

In the city, the population was spread out with 34.6% under the age of 18, 11.2% from 18 to 24, 27.5% from 25 to 44, 17.2% from 45 to 64, and 9.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $24,468, and the median income for a family was $26,186. Males had a median income of $21,739 versus $17,116 for females. The per capita income for the city is $9,762. About 31.6% of families and 35.7% of the population were below the federal poverty line, including 48.4% of those under the age of 18 and 31.5% of those 65 or over.[33]

As of the estimated census of 2015, the city's population stands at 183,887 with 50,207 households.[34] The current metropolitan area estimates count 422,156 residents, an increase from 406,220 and its combined statistical area stood at 444,059 residents, an increase from 428,354, according to the census of 2010.[35][36] It is the 131st largest city in the United States along with the 126th largest metropolitan area and the 93rd largest combined statistical area.

Economy

An important pillar of the economy is the Port of Brownsville. The port, located 2 miles (3.2 km) from the city, provides an important link between the road networks of nearby Mexico, and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway of Texas.[37]

Top employers

According to the Brownsville Economic Development Council (BEDC),[38] the top employers in the city as of May 2015 were:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brownsville Independent School District | 7,670 |

| 2 | Cameron County | 1,950 |

| 3 | University of Texas Rio Grande Valley | 1,734 |

| 4 | Keppel AmFELS | 1,650 |

| 5 | Walmart | 1,413 |

| 6 | Abundant Life Home Health | 1,300 |

| 7 | City of Brownsville | 1,227 |

| 8 | Caring For You Home Health | 1,200 |

| 9 | H-E-B Grocery | 975 |

| 10 | Maximus | 950 |

Technology growth in the 2010s

SpaceX is building the SpaceX South Texas Launch Site, a private space launch facility east of Brownsville on the Gulf Coast.[39][40]

The new launch facility is expected to draw US$85 million to the city of Brownsville and eventually generate approximately US$51 million in annual salaries from some 500 jobs created by 2024.[41]

The facility itself is projected to employ 75–100 full-time workers in the early years with up to 150 full-time employees/contractors by 2019.[42]

As of October 2014, the University of Texas at Brownsville and the Brownsville Economic Development Council (BEDC), in collaboration with SpaceX, are building radio-frequency (RF) technology facilities for STARGATE (Spacecraft Tracking and Astronomical Research into Gigahertz Astrophysical Transient Emission). The facility is intended to provide students and faculty access to RF technologies widely used in spaceflight operations, and will include satellite and spacecraft tracking.[43]

BEDC purchased five lots in Boca Chica Village totaling 2.3 acres (0.93 ha) near the SpaceX launch site and renamed it as the STARGATE subdivision. The beach location will include a 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) tracking center."[44]

STARGATE has received several startup grants including US$1.2 million from the US Economic Development Administration.[45]

Government

City government

Brownsville has a council–manager style of government. The mayor and six city commissioners, two at-large and four district, serve staggered four-year terms. Elections are held for one at-large and two district seats every two years. Municipal elections are held on the first Saturday of May in odd numbered years. Once a winner is determined, the commissioner-elect will be seated at the next regular meeting of the Brownsville City Commission. City elected officials are non-partisan, meaning that they do not have a party affiliation. They may be personally affiliated with a political party but this has no bearing on the office.

Visit the City of Brownville, Texas online

As of 2015, the members of the commission were:[46]

- Mayor: Antonio "Tony" Martinez (since 2011)

- Commissioner At-Large "A": Cesar de Leon (since 2015)

- Commissioner At-Large "B": Dr. Rose M.Z. Gowen (since 2009)

- Commissioner District 1: Ricardo Longoria Jr. (since 2003)

- Commissioner District 2: Jessica Tetreau-Kalifa (since 2011)

- Commissioner District 3: Joel Munguia (since 2017)

- Commissioner District 4: Ben Neece (since 2017)

The next regular elections for the city will occur in the following years:[46]

- Mayor: 2019

- At-Large "A": 2019

- At-Large "B": 2021

- District 1: 2019

- District 2: 2019

- District 3: 2021

- District 4: 2021

The city commission appoints the city manager. Since 2017, the city manager is Michael Lopez.[47] The city commission also appoints a six-member public utilities board for a four-year term. Members are limited to two consecutive or non-consecutive terms. The mayor is an ex-officio member of the board. The current board members are:[48]

- Nurith Galonsky, chair

- Rafael Vela, cice-chair

- Rafael S. Chacon, secretary/treasurer

- Martin C. Arambula, member

- Noemi Garcia-Martinez, member

- Edna Oceguera, member

County Commission representation

The majority of Brownsville is represented by two of the four commission precinct commissioners. They have staggered four-year terms. County offices are partisan, thus the Democratic and Republican Parties will hold primaries in the March of the year of the year that office term expires. The Candidate who receives the highest amount of votes will then receive their party's nomination. The Libertarian Party selects their candidate by means of their County Convention. The nominees of each party will then run in a general election in November, the winner of which will become the Commissioner the following January.

The following commissioners represent at least part of the City of Brownsville:

- South and East Brownsville are represented by Precinct 1 Commissioner, Sofia Benavides (D). (since 2006)

- North, Central Brownsville are represented by Precinct 2 Commissioner, Alex Dominguez (D). (since 2014)

- A sizable portion of Brownsville farm and scrub land north of FM 511 is represented by Precinct 3 Commissioner, David Garza (D). (since 2001)[49]

The chief executive of the county or the Cameron County Judge is Pete Sepulveda, Jr. (N/A) (since 2015)[50]

The next regular elections for the County Commission Precincts 1, 2, and 3 will occur in the following years:

- Precinct 1: 2016

- Precinct 2: 2018

- Precinct 3: 2016

- Judge: 2018

State representation

The City of Brownsville falls under two State House of Representatives districts. Each representative has a two-year term and is elected in the same manner as other partisan elected officials.

- District 37: Rene O. Oliveira (D) (since 1991)[51]

- District 38: Eduardo "Eddie" Lucio III (D) (since 2007)[52]

All of Brownsville is represented by Texas Senatorial District 27, the incumbent senator is a Democrat, Eduardo "Eddie" Lucio Jr. (1991–present)[53]

- Brazos Island Brazos Island State Scenic Park, also known as Brazos Island State Recreation Area, which has 217 acres

- Boca Chica State Park

- Las Palomas Wildlife Management Area – Boca Chica Unit[54]

- Resaca de la Palma, is a 1,200-acre (4.9 km2) State Park and World Birding Center site located to the northwest of Brownsville, Texas.[55]

- Texas Department of Public Safety TxDPS located at 2901 Paredes Line Road

- Texas Attorney General's Office, Child Support Division[56]

Federal representation

All of Brownsville is represented by U.S. Congressional District 34, the incumbent Representative is Filemon Vela Jr., elected in 2013, (D).[57]

The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Brownsville. The Brownsville Main Post Office is located at 1535 East Los Ebanos Boulevard.[58] Downtown Brownsville is served by the Downtown Brownsville Post Office at 1001 East Elizabeth Street.[59]

There is also a National Weather Service office and doppler radar site in 20 South Vermillion Avenue Brownsville, Texas. They provide forecasts and radar coverage for Deep South Texas and the adjacent coastal waters.[60]

Social Security Administration

- Social Security Administration located at 3115 Central Boulevard

Federal Courthouse

- The Reynaldo G. Garza – Filemon B. Vela United States Courthouse is located at 600 E. Harrison Street[61]

Military installations

- The Brownsville Armed Forces Reserve Center (AFRC) located at Woodruff Avenue host units from the United States Army Reserve and the Texas Army National Guard.[62]

- The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) located at 80 Fort Brown[63]

National parks

Education

Universities and colleges

- University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (previously University of Texas–Pan American and University of Texas at Brownsville)

- Texas Southmost College[65]

- The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Public Health (UTSPH), Brownsville Regional Campus

The School of Public Health (UTSPH) opened in 2001 as part of the legislated Regional Academic Health Center program, or RAHC and is physically located on the campus of the University of Texas at Brownsville. UTSPH – Brownsville is a regional campus of the University of Texas School of Public Health statewide network which offer students a graduate certificate in public health and the Master of Public Health (M.P.H.) graduate degree.

Starting in 2009, the Brownsville Regional Campus also began offering a PhD program in Epidemiology and a Doctorate in Public Health (DrPH) in Health Promotion, the only programs of their kind in South Texas. Major public health concerns of the faculty and researchers found here in the Lower Rio Grande Valley Texas include diabetes, tuberculosis, obesity, cardiovascular disease and hepatitis. Other areas of public health significance include physical activity, behavioral journalism, healthy living, diet and lifestyles activities. The Brownsville Regional Campus is also developing a strong research focus in genetics and its relationship to infectious and chronic disease.[66]

Vocational schools

- South Texas Vocational Technical Institute[67]

- Brightwood College Brownsville Campus (formerly known as Kaplan College)[68]

- Southern Careers Institute Brownsville Campus[69]

Primary and secondary schools

Public schools

Most of Brownsville is served by Brownsville Independent School District. The BISD counted its total enrollment in the 2014–15 school year at 48,155 students in 58 schools.[70] It is the 17th largest school district in Texas. A portion of northern Brownsville is served by the Los Fresnos Consolidated Independent School District.

In addition, Brownsville residents are allowed to apply to magnet schools operated by the South Texas Independent School District, as well as BISD magnet schools. Each BISD high school has a magnet school within the school, Gladys Porter High School is home to the High School for Engineering Professions. Homer Hanna High School is home of the Tech Med Magnet Program for Medical and Health Professions. Lopez High School houses the district's Fine Arts Academy, James Pace High School has a Criminal Justice Magnet School and Simon Rivera High School hosts the International Business Magnet School.

Magnet schools

- The Science Academy of South Texas[71]

- Mathematics and Science Academy UTB

State charter schools

- Raul Yzaguirre School for Success

- Sentry Technology Prep Charter High School

- IDEA Frontier Academy and College Preparatory

- IDEA Brownsville Academy and College Preparatory

- IDEA Riverview Academy and College Preparatory

- Harmony Science Academy-Brownsville (K–12)

- Brownsville Early College High School

- Math and Science Academy-UTB

- Athlos Leadership Academy (K-9)

- Livingway Leadership Academy (Pre-K-5)

Private and parochial schools

Grades 9-12:

- Saint Joseph Academy (grades 7 through 12)

- Valley Christian High School

- First Baptist High School

Grades 1-8:

- Brownsville SDA School

- Episcopal Day School

- First Baptist School

- Faith Christian Academy

- Guadalupe Regional Middle School

- Incarnate Word Academy

- Kenmont Montessori School

- St. Luke's Catholic School

- St. Mary's Catholic School

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Brownsville operates area Catholic schools.

Public libraries

The Brownsville Public Library System

University libraries

- Arnulfo L. Oliveira Memorial Library located at 80 Fort Brown

- University Boulevard Library located at 2035 University Blvd.[76]

Transportation

Railroad

Several attempts were made to attract a railroad, but not until 1904 did the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico Railway reach the City of Brownsville. In 1910 a railroad bridge was constructed between Brownsville and Matamoros (Mexico) and regular service between the two towns began. The introduction of the rail link to Brownsville opened the area for settlement of northern farmers, who began arriving in the lower Rio Grande valley in large numbers after the turn of the century.

The new settlers cleared the land of brush, built extensive irrigation systems and roads, and introduced large-scale truck farming. In 1904 H. G. Stillwell, Sr., planted the first commercial citrus orchard in the area, thus opening the way for citrus fruit culture, one of the Valley's leading industries. The expansion of farming in the area and the railroad link to the north brought new prosperity to Brownsville and spurred a host of civic improvements.[77]

Today, the Brownsville and Rio Grande International Railroad (reporting mark BRG) Brownsville and Rio Grande International Railroad is a terminal switching railroad headquartered in Brownsville, Texas. BRG operates 45 mi (72 km) of line at the Port of Brownsville, and interchanges with Union Pacific and TFM. BRG traffic includes steel, agricultural products, food products, and general commodities.[78]

Mass transit

Established in mid-Brownsville in 1978, with expanding bus service to rapidly developing North Brownsville, the Brownsville Urban System (BUS), currently known as the Brownsville Metro, consists of 3 hubs running 13 routes covering a large portion of Brownsville. The system provides 11 paratransit vans to disabled passengers, meeting the standards for the Americans with Disabilities Act. It is the only mass transit system in its county and the largest in the Rio Grande Valley. The system also provides service to around 1.5 million passengers per year.[79] One of its main terminals is located at 755 International Blvd., called La Plaza at Brownsville.[80]

Highways

Brownsville is served by the following Interstate Highways, U.S. Routes, and Texas State Highways:

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

International bridges

Brownsville has three international bridges:

- The Brownsville & Matamoros International Bridge (B&M), known locally as the "Old Bridge." The B&M International Bridge also serves as an international railway for Union Pacific.

- Gateway International Bridge, known locally as the "New Bridge" despite the fact that it's no longer the city's newest international bridge.

- The Veterans International Bridge at Los Tomates, or locally simply known as the "Los Tomates" or "Veterans" bridge.

Airport

Brownsville has its own city-owned airport, the Brownsville/South Padre Island International Airport. The airport is used for general aviation and is served by United Airlines (service to Houston-Intercontinental), and Envoy Air (service to Dallas-Fort Worth).[81]

Cycling and hiking

The city of Brownsville currently operates seven cycling paths around the area. Around 64 miles of the city's streets are bicycle trails and on-street bike lanes. The city's move towards a more environmental-friendly area has created the nickname "The Bicycling Capital of the Rio Grande Valley." The current operating cycling paths are:[82]

- Brownsville Historic Battlefield Trails, a national trail spanning 9 miles

- Paseo de la Resaca Trails, a 7-mile trail with both ends meeting at the Brownsville Sports Park

- Monte Bella Mountain Bike Trail, a 6.3-mile trail located in North Brownsville

- Belden Trail, located in Downtown Brownsville; connects the West portion of the city with its adjacent areas

- Brownsville Sports Park Hike & Bike Trail

- Resaca de la Palma State Park Trails, an 8-mile trail owned by a state park

- Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge, part of the National Wildlife Refuge System

Culture

Festivals and parades

During mid to late February, Charro Days takes place in Brownsville. The holiday is a two-nation fiesta celebrating the friendship between Brownsville and its sister city and border town, Matamoros. The celebration attracts around 50,000 guests per year. It is accompanied with El Grito, a joyous shout originating in Mexican culture[83] as well as a visit from the Mr. Amigo Association. Honorees who have attended previous events include Vicente Fernandez and Mexican actors Arath de la Torre and Eduardo Yanez. Sombrero Festival is another celebration taking place around the same time as Charro Days. The festival is a three-day event consisting of performances from rock, tejano and corrido artists as well as a variety of contests.

- AirFiesta is an air show hosted in mid-February in Brownsville. The event consists of professional aerobatics performers as well as militia from the U.S. Army, Navy and Air Force. The event takes place at the Brownsville/South Padre Island International Airport. An arts and craft show is also hosted along with the event.

- The Latin Jazz Festival is an annual musical event hosted around early October in Downtown Brownsville. The event is a 3-day celebration of Latin Jazz performers, art and dance. The first festival took place in 1997 and was founded by Tito Puente, a composer from New York City known as the "King of Latin Jazz". Local artists and bands perform songs by Latin Jazz artists.

- The city hosts two different parades throughout the year. The Fourth of July Parade is an annual parade hosted in the Fourth of July in Downtown Brownsville. The event has the same route as Charro Days and was created in 2000. The Winter Break Parade is an annual parade also hosted in Downtown Brownsville around early December. The parade consists of floats made by different schools around the city.

- St. Mary, Mother of the Church Fall Festival is a Catholic festival held in 1914 Barnard Road. The event features live music and auction. It is hosted by the Catholic Diocese of Brownsville. The organizations also holds festivals in nearby areas such as McAllen, Edinburg and Mission.

Museums

Children's Museum of Brownsville is a museum for young children consisting of educational exhibits and learning centers. Building efforts commenced in 2000 with the museum opening in 2005. It is located next to the Camille Lightner Playhouse in the center of Dean Porter Park in 501 E. Ringgold Street.[84]

Founded in 1935, the Brownsville Museum of Fine Arts is an arts museum featuring exhibitions on Egyptian and Astronomical art. The museum was formerly known as the Brownsville Art League, formed by a group of eight women. The museum underwent a renovation in 1960, featuring a 4,000 sq ft studio and in 2002, it changed its name to its current name also receiving a 17,000 sq foot renovation. It is located in Downtown Brownsville at 660 East Ringgold Street.[85][86]

The Historic Brownsville Museum is a historic museum opened to the public in 1986. The building was used as a Spanish Colonial Revival passenger depot and was later abandoned. The museum features Spanish architecture and education programs. It also hosts meeting for various organizations including City and State officials. Several renovations were made to give the museum a more "present" look such as the addition of a Spanish-style fountain, a courtyard and an engine building.[87][88]

Built in 1850 by Henry Miller, owner of the Miller Hotel in downtown Brownsville, the Stillman House Museum was owned by city founder Charles Stillman and Mexican consul Manuel Pérez Treviño. It was the site of meetings with Mexican president Porfirio Diaz. The great grandson of Stillman bought the house after the previous homeowners sold it and was donated to the city after renovations. It opened to the public in 1960. The home experienced damage from Hurricane Dolly in 2008 and reopened to the public the next year after renovations were made.[89]

Costumes of the Americas Museum is an indigenous clothing museum located in 501 Ringgold Street. Inspired by Bessie Kirkland Johnson, the museum was opened in 1997, featuring clothing from indigenous people in several Mexican states and other Latin American countries.[90]

The Commemorative Air Force Museum is an aircraft museum located in 955 Minnesota Ave., next to the Brownsville/South Padre Island International Airport. The museum features World War II aircraft and also holds tours on the early events leading to wars in Asia and Europe. It also features the stories of aviation pilots who were part of the 201st Mexican Fighter Squadron and hosts the annual AirFiesta in February.[91]

Theatre

Jacob Brown Auditorium is an performing arts auditorium located in Downtown Brownsville. The venue has a 1,593 person capacity and has a variety of functions including banquet ceremonies, conference meetings and being a reception hall.[92] It is part of the University of Texas at Brownsville campus, now University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

The Arts Center is a performing arts and concert venue in conjunction with Texas Southmost College. It is associated with several theater organizations including Chamber Music America and the Association of Performing Arts Presenters. The center is strictly used for theater shows, while only using the lobby for meetings. It is currently the only Arts Center currently operating south of San Antonio.[93]

Camille Lightner Playhouse is a performing arts auditorium founded in 1964 and located on 500 E Ringgold Street. The venue hosts auditions for local and Broadway plays, as well as hosting the Henri Awards, an awards show honoring the best in the venue's staff. It also holds a summer workshop for younger children and holds a reception hall at the DeStefano Room.[94]

Arts

The Brownsville area is full of well-established art galleries and museums that represent not only art of the region and Mexico but feature traveling exhibits from around the world.[95]

Films made or inspired by Brownsville

| Year | Title | Lead actor(s)[96] |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Back Roads | Sally Field, Tommy Lee Jones[97] |

| 2000 | The President's Man | Chuck Norris, Dylan Neal |

| 2004 | Pink Punch | Adal Ramones, Omar Chaparro |

| 2011 | The Big Year* | Jack Black, Owen Wilson[98] |

| 2012 | Get the Gringo | Mel Gibson[99] |

| 2013 | A Night in Old Mexico | Robert Duvall[100] |

| 2015 | Endgame | Efren Ramirez, Rico Rodriguez[101][102] |

| 2017 | The Green Ghost | Danny Trejo[103] |

* The Big Year featured a scene where Brownsville, Texas was written in front of the screen. Film draws inspiration from wildlife in the Rio Grande Valley.

TV shows made or inspired by Brownsville

| Year | Title | Lead actor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Friday Night Lights | Kyle Chandler, Connie Britton[104] |

| 2011 | Border Wars | N/A[105] |

| 2017 | Jeff Ross Roasts The Border: Live From Brownsville, Texas | N/A |

Sports

Each year, Brownsville hosts the Jackie Robinson World Series for nine-year-old baseball players. In 1920 the St. Louis Cardinals held spring training in Brownsville.[106] In 2011 and 2013, University of Texas at Brownsville Ocelots team captured the NAIA Women's Volleyball National Championship in Sioux City, Iowa at the Tyson Events Center.

These are the golf courses operating within the Brownsville city limit:

Media

Newspapers

- The Brownsville Herald

- Valley Morning Star

- The Monitor

- Island Breeze

- Coastal Current

- The Collegian

Television

The Brownsville area is served by numerous local television affiliates:

- XHRIO-TV 2 MundoFox – Matamoros, Tamaulipas

- KGBT-TV 4 CBS – Harlingen

- KRGV-TV 5 ABC – Weslaco

- XHAB 7 Televisa Regional Matamoros, Tamaulipas

- XERV 9 Canal de las Estrellas Matamoros, Tamaulipas

- XHOR 14 Azteca 7 Reynosa, Tamaulipas

- KXFX-CD 20 Fox – Brownsville

- KCWT-CD 21 The CW – McAllen

- KVEO-TV 23 NBC – Brownsville

- KMBH 38 PBS – Harlingen

- KTLM 40 Telemundo – McAllen

- KLUJ-TV 44 TBN – Harlingen

- KNVO-TV 48 Univision – McAllen

- KNWS-LP 64 Azteca America – Brownsville

Radio

- KVNS 1700 AM Fox Sports Radio

- KURV 710 AM News Talk

- KFRQ 94.5 FM Rock

- KKPS La Nueva 99.5 99.5 FM Tejano

- KNVO 101.1 FM

- XEEW-FM 97.7 FM Los 40 Latin Pop

- KVLY 107.9 FM MIX FM Contemporary Hit Radio

- KBFM Wild 104 104.1 FM Hip Hop, Contemporary R&B, Pop, Reggaeton

- KBNR 88.3 FM Radio Manantial (Spanish Christian)

- KTEX 100.3 FM Country

- XHMLS Exa FM 91.3 FM Latin Pop

- XHAAA "La Caliente" 93.1 FM

- KXIQ-LP 105.1 FM Brownsville Society for the Performing Arts BSPA[109] [110]

- XHNA Mega 105.9 FM Regional Mexican

- KHKZ Kiss 106.3 Adult Contemporary

- KVMV 96.9 FM Contemporary Christian

- KJJF/KHID 88.9 Public Radio 88 FM NPR and Performance Today

- KJAV 104.9 Jack FM Adult Hits

- UTB Radio[111] (formerly UTB Sting Radio) Internet Radio with diverse DJ Shows e.g., Thinking Out Loud[112] philosophy programming

Points of interest

Local attractions include the Gladys Porter Zoo, the Brownsville Museum of Fine Art, Camille Lightner Playhouse, a historical downtown with buildings over 150 years old, the Port of Brownsville, and the Children's Museum of Brownsville. There is also easy access to South Padre Island and the Mexican city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas. Sunrise Mall is the largest shopping mall in the city of Brownsville.

Since being remodeled in 2015 the mall has become the primary mall in the Brownsville-Harlingen metroplex. Brownsville previously had another shopping mall, Amigoland Mall by Simon, though the building has since been purchased by the University of Texas at Brownsville (now University of Texas Rio Grande Valley) after many of its tenants moved from Amigoland to Sunrise.

Sanctuary

Notable people

- James Carlos Blake: award-winning novelist, received his elementary education at Saint Joseph Academy[114]

- Shelbie Bruce: actress.[115]

- José Tomás Canales: lawyer, writer, politician.[116]

- Oscar Casares: author and professor of creative writing at UT Austin; published two books about Brownsville, including Amigoland (2009)

- Carlos Cascos: outgoing county judge of Cameron County; incoming Secretary of State of Texas.

- Buddy Garcia: 2012 member of the Texas Railroad Commission; now resides in Austin.

- Reynaldo G. Garza (1915–2004): Judge of Brownsville was first appointed to the United States District Court in 1961 by U.S. President John F. Kennedy, and to the United States Court of Appeals by President Jimmy Carter in 1978.

- Tony Garza: former U.S. Ambassador to Mexico.

- Gilberto Hinojosa: County judge of Cameron County from 1995 to 2007, unseated in 2006 by Republican Carlos Cascos; Texas Democratic Party chairman since 2012.

- Mifflin Kenedy (1818–95): South Texas rancher and steamboat businessman; interred at Buena Vista Burial Park in Brownsville.

- Bernard L. Kowalski (1929–2007): film and television director.

- Kris Kristofferson: country music star, singer and songwriter, 2004 Hall of Fame Inductee, and actor[117]

- Eddie Lucio Jr.: member of the Texas State Senate from Brownsville since 1991; pro-life activist.

- Eddie Lucio III: member of the Texas House of Representatives from Brownsville since 2007.

- Bianca Marroquín: Mexican musical theatre and television actress.[118]

- Domingo Martinez: author of The Boy Kings of Texas, a Memoir

- Grace Napolitano: U.S. Representative for California's 32nd congressional district

- Jose Rolando Olvera Jr.: U.S. District Judge for the Southern District of Texas appointed by U.S. President Barack Obama in 2015[119]

- Americo Paredes (1915–99): author of George Washington Gomez[120]

- Rudy Ruiz: award-winning Latino author, entrepreneur and advocate; attended Saint Joseph Academy.[121]

- Ramón Saldívar: scholar of Chicano literature and culture, awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama in 2012, teaches at Stanford University.

- Julian Schnabel: "neo-expressionist" painter and Academy Award-nominated, Golden Globe winner and director of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

- Bruce Sterling: author of the Mirrorshades anthology and one of the pioneers of the cyberpunk genre.

- Emeraude Toubia: actress (Shadowhunters).[122]

- Benjamin D. Wood: noted education expert.

- Jaime Zapata (1979–2011): U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent who was ambushed, shot, and killed by Los Zetas in San Luis Potosí, Mexico.[123] He was returning from a meeting in Mexico City; Victor Avila, another agent who accompanied him, was wounded in the same incident.[124]

Sister cities

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

References

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Brownsville city, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Brownsville housing plan created as population grows". ValleyCentral.com. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014 - United States -- Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico (GCT-PEPANNRES)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Matamoros-Brownsville". World Gazetteer. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ↑ "In America's Poorest City, a Housing Breakthrough – CityLab". Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ↑ Salinas, Gilberto (July 2, 2005). "Brownsville-McAllen fastest growing cities in Texas". The Brownsville Herald.

- ↑ Plume, Janet (November 2004). "New Route from Asia?". Journal of Commerce. 5 (44): 42. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ "About Brownsville". City of Brownsville: Brownsville Public Library. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Governor's ED Team Receives Leadership Award" (PDF). Brownsville's Economic Development Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Wong, Vanesa (2011-06-27). "Texas town is the cheapest place to live in US". MSN News. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ Scribner, John. "The Texas Navy". Texas Military Forces Museum. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ Thompson, Jerry D. (2007). Cortina: defending the Mexican name in Texas. Texas A&M University Press. p. 332.

- ↑ Delaney, Robert W. (April 1955). "Matamoros, Port for Texas during the Civil War". 58 (4). The Southwestern Historical Quarterly: 487. JSTOR 30241907.

- ↑ "Tamaulipas y la guerra de Independencia: acontecimientos, actores y escenarios" (PDF). Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "The Mexican Revolution: Conflict in Matamoros". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ Yorke Stevenson, Sara (2004). Maximilian in Mexico: A Woman's Reminiscences of the French Intervention, 1862 to 1867. Kessinger Publishing. p. 168. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ↑ Pettit, Elizabeth D. (June 12, 2010). "FORT BROWN". tshaonline.org.

- ↑ Miller, Michael E.; Brown, Emma; Davis, Aaron C. (14 June 2018). "Inside Casa Padre, the converted Walmart where the U.S. is holding nearly 1,500 immigrant children". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ "City's bag ban carries onward". Brownsvilleherald.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ MSNBC.com "America's Cleanest Cities", msnbc.msn.com; accessed February 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Web Soil Survey". Websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L., and McMahon, T. A.: Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 11, 1633–1644, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Brownsville, TX". The Weather Channel. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Five Weirdest White Christmases: #1 South Texas...Snow Kidding! (2004)". The Weather Channel. December 24, 2014.

- ↑ "The Valley's White Christmas!: Miracles Happen as Snow Accumulates Christmas Morn' in 2004". National Weather Service.

- ↑ "Station Name: TX Brownsville". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ↑ "WMO climate normals for Brownsville/INTL, TX 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Brownsville demographics". brownsvilletx.areaconnect.com. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2010–2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ↑ "QuickFacts: Brownsville city, Texas". United States Census. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 - United States -- Metropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". United States Census. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 - United States -- Combined Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". United States Census. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ↑ "About Us". Port of Brownsville.

- ↑ Brownsville Economic Development Council Archived 2014-05-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2014-09-22). "SpaceX Breaks Ground on Texas Spaceport". Space News. Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ↑ "Brownsville area candidate for spaceport". brownsvilleherald.com. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ↑ Jervis, Rick (2014-10-06). "Texas border town to become next Cape Canaveral". USA Today. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ Nield, George C. (April 2014). Draft Environmental Impact Statement: SpaceX Texas Launch Site (PDF) (Report). 1. Federal Aviation Administration, Office of Commercial Space Transportation. Archived from the original on 2013-12-07.

- ↑ Clark, Steve (2012-11-26). "'STARGATE' facility may be coming to Brownsville". The Monitor. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (2014-09-25). "SpaceX makes more moves". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 2014-09-27.

- ↑ "STARGATE to receive $1.2 million EDA grant". Brownsville Herald. 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- 1 2 "The Brownsville City Commission". City of Brownsville. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ↑ "City Manager's Office". City of Brownsville. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Board of Directors: Brownsville Public Utilities Board". Brownsville Public Utilities Board. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Commissioner Pct. 3, David A. Garza". Cameron County. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "County Judge, Pete Sepulveda, Jr". Cameron County. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Texas House member: Rep. Oliveira, René O. District 37". Texas House of Representatives. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Texas House member: Rep. Lucio III, Eddie District 38". Texas House of Representatives. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Senator Eddie Lucio, Jr.: District 27". The Texas State Senate. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Las Palomas Wildlife Management Area -Boca Chica Unit". Got Parks. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Resaca de la Palma State Park Opens Near Brownsville". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Child Support Local Field Offices". Texas Attorney General's Office. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Congressman Filemon Vela: Serving South Texas (TX-34)". Congressman Filemon Vela, Jr. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Brownsville 1535 E Los Ebanos Blvd Brownsville, TX 78520-9998". United States Postal Service. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Downtown Brownsville 1001 E Elizabeth St Fl 1 Brownsville, TX 78520-9995". United States Postal Service. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office: Brownsville, TX". National Weather Service. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "The Reynaldo G. Garza – Filemon B. Vela United States Courthouse". United States Courthouse. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Brownsville Armed Forces Reserve Center". United States Green Building Council. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Reserve Officers Training Corps". University of Texas at Brownsville. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Palo Alto National Historic Park". National Park Service. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ↑ "Texas Southmost College". TSC. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ↑ "University of Texas School of Public Health–Brownsville". Sph.uth.tmc.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-09-08. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "South Texas Vocational Technical Institute". South Texas Vocational Technical Institute. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ "Brightwood College in Brownsville, TX". Brightwood College. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Southern Careers Institute". Southern Careers Institute. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Peak Enrollment, BISD Schools, Student Support Services". Brownsville Independent School District.

- ↑ Long, Gary (April 6, 2013). "$29M medical academy to be built in Brownsville". Valley Morning Star.

- 1 2 "Visit Us". Brownsville Public Library System. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Library Locations and Hours of Operation Archived July 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.", Brownsville Public Library System; retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Cameron County Law Library". Cameron County. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ↑ "County Law Library". Texas State Law Library. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ↑ "University Libraries". UTB. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "The Handbook of Texas: Brownsville". Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ "About Brownsville & Rio Grande International Railway, LLC". OmniTRAX.

- ↑ "Human Service-Public Transit Coordination Plan" (PDF). Lower Rio Grande Valley Development Council. p. 24.

- ↑ "Welcome to Brownsville Metro". City of Brownsville.

- ↑ "American Eagle Airlines Launches Nonstop Jet Service Between Brownsville, Texas, and Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport" (Press release). American Eagle Airlines. June 11, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Hike & Bike Trails". Brownsville Convention & Visiting Bureau. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ↑ "El Grito: What Is It And What Does It Mean?". The Huffington Post. September 15, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Museum History". Children's Museum of Brownsville. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Brownsville Museum of Fine Art". Brownsville Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Exhibitions". Brownsville Museum of Fine Arts. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Historic Brownsville Museum". Brownsville Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Historic Brownsville Museum". Mitte Cultural District. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Brownsville Historical Association – Stillman House". Brownsville Historical Association. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Mission & History". Costumes of the Americas Museum. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "CAF wing: Changes necessary to survive". Brownsvilleherald.com. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Fort Brown Memorial Center". Brownsville Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Arts Center at Texas Southmost College". Brownsville Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ "The DeStefano Room". Camille Lightner Playhouse. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ "The Brownsville Heritage Complex". Brownsville History. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Most Popular Titles With Filming Locations Matching "brownsville texas"". IMDb.

- ↑ Lester, Peter (June 15, 1981). "Once a Lone Star, Texan Tommy Lee Jones Takes a New Bride—and a Powder from L.a." People.

- ↑ Henry, Ryan (November 7, 2011). "BIG year: RGV Birding Festival draws celebrities". The Monitor.

- ↑ Chapa, Sergio (June 16, 2012). "Mel Gibson movie filmed in Brownsville skips American theaters". KGBT-TV.

- ↑ Leydon, Joe (March 10, 2014). "SXSW Film Review: 'A Night in Old Mexico'". Variety.

- ↑ Nelson, Aaron (May 18, 2013). "Brownsville's chess success inspires movie". San Antonio Express-News.

- ↑ Martinez, Michael (September 24, 2015). "Indie filmmaker Carmen Marron captures real-life chess triumph of Latino school". CNN.

- ↑ White, Tyler (March 9, 2015). "Danny Trejo shooting new superhero film in South Texas". mySanAntonio.

- ↑ Phillips, Carl (September 17, 2007). "Friday Night Lights films in Brownsville, SPI". The Brownsville Herald.

- ↑ "'Border Wars' to shed light on cartels, Mexican ties to Brownsville". Valley Morning Star.

- ↑ The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. Sterling Publishing. 2007. p. 1789. ISBN 1-4027-4771-3.

- ↑ "Valley International Country Club". VICC. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Rancho Viejo Resort and Country Club". rvrcc. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.artsinbrownsville.org/radio.html

- ↑ https://radio-locator.com/info/KXIQ-FL

- ↑ "UTB Radio". The University of Texas at Brownsville. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ "Thinking Out Loud". Philosophy Club at UTB. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Sabal Palm Audubon Sanctuary". Audobun Texas. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ McMillan, Maura. "A Tribe of One," Firsts: the Book Collector's Magazine, May 2001

- ↑ Hispanic heritage awards. Hispanic Heritage Foundation. 2006. p. 1971.

- ↑ 'Judge J. T. Canales Dies at Brownsville,' Del Rio Herald New, April 1, 1975, pg. 16

- ↑ "Kris Kristofferson Hall of Fame Induction". Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Dancer with Brownsville ties now starring in musicals". The Brownsville Herald. July 31, 2003. Archived from the original on August 15, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ↑ "President Obama Nominates Seven to Serve on the United States District Courts". whitehouse.gov. 2014-09-18. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ↑ "Américo Paredes: Biography". Lib.utexas.edu. 1915-09-03. Archived from the original on 2013-09-25. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ Brito, Victoria (November 21, 2014). "Author to Watch: Rudy Ruiz". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Brownsville native on television tonight". The Monitor. May 16, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ "6 Zetas arrested in death of agent". San Antonio News. February 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Jaime Zapata, U.S. Immigration And Customs Enforcement Agent, Killed In Mexico". The Huffington Post. February 16, 2011.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brownsville, Texas. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brownsville. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Brownsville (Texas). |