Houston

| Houston, Texas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| City of Houston | |||

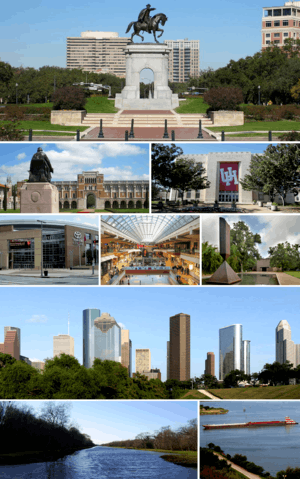

From top, left to right: Sam Houston Monument, Rice University, University of Houston, Toyota Center, The Galleria, Broken Obelisk, Downtown Houston, George Bush Park, Houston Ship Channel | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): Space City (official) more... | |||

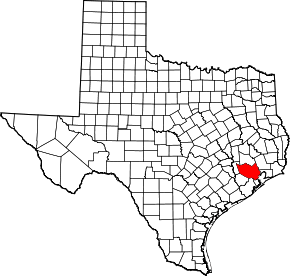

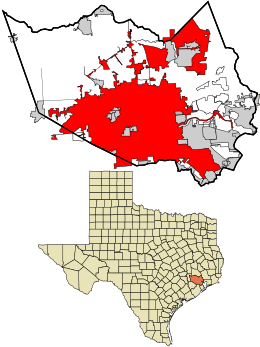

Location of Houston city limits in and around Harris County | |||

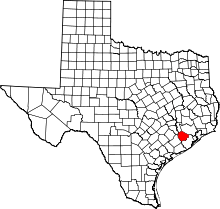

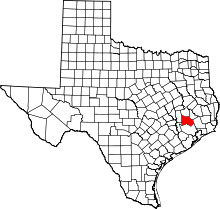

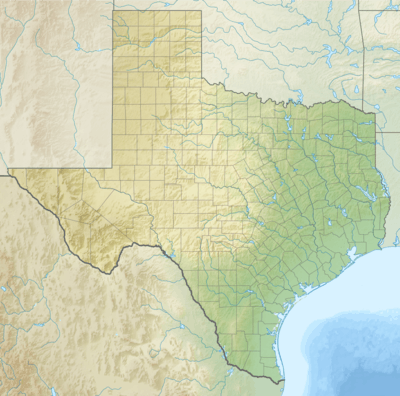

Houston, Texas Location in Texas  Houston, Texas Houston, Texas (the US) | |||

| Coordinates: 29°45′46″N 95°22′59″W / 29.76278°N 95.38306°WCoordinates: 29°45′46″N 95°22′59″W / 29.76278°N 95.38306°W | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | Texas | ||

| Counties | Harris, Fort Bend, Montgomery | ||

| Incorporated | June 5, 1837 | ||

| Named for | Sam Houston | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor–council | ||

| • Body | Houston City Council | ||

| • Mayor | Sylvester Turner (D) | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 627 sq mi (1,623.92 km2) | ||

| • Land | 599.59 sq mi (1,552.9 km2) | ||

| • Metro | 1,062 sq mi (2,750 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 80 ft (32 m) | ||

| Population (2010)[1] | |||

| • City | 2,099,451 | ||

| • Estimate (2017) | 2,312,717[2] | ||

| • Rank | US: 4th | ||

| • Density | 3,660/sq mi (1,414/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 4,944,332 (7th U.S.) | ||

| • Metro | 6,313,158 (5th U.S.) | ||

| • Demonym | Houstonian[3] | ||

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) | ||

| ZIP Codes | 770xx, 772xx (P.O. Boxes) | ||

| Area code(s) | 713, 281, 832, 346 | ||

| FIPS code | 48-35000[4] | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1380948[5] | ||

| Primary Airport |

George Bush Intercontinental Airport IAH (Major/International) | ||

| Secondary Airport |

William P. Hobby Airport HOU (Regional) | ||

| Interstates |

| ||

| U.S. Routes |

| ||

| Rapid Transit |

| ||

| Website | houstontx.gov | ||

Houston (/ˈhjuːstən/ (![]()

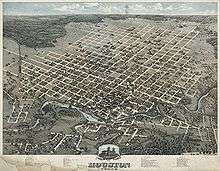

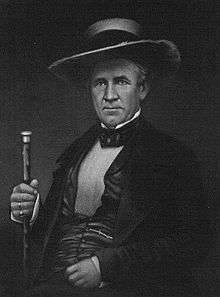

Houston was founded by land speculators on August 30, 1836,[8] at the confluence of Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou (a point now known as Allen's Landing)[9] and incorporated as a city on June 5, 1837.[10] The city is named after former General Sam Houston, who was president of the Republic of Texas and had won Texas' independence from Mexico at the Battle of San Jacinto 25 miles (40 km) east of Allen's Landing.[10] After briefly serving as the capital of the Republic in the late 1830s, Houston grew steadily into a regional trading center for the remainder of the 19th century.[8]

The arrival of the 20th century saw a convergence of economic factors which fueled rapid growth in Houston, including a burgeoning port and railroad industry, the decline of Galveston as Texas' primary port following a devastating 1900 hurricane, the subsequent construction of the Houston Ship Channel, and the Texas oil boom.[8] In the mid-20th century, Houston's economy diversified as it became home to the Texas Medical Center—the world's largest concentration of healthcare and research institutions—and NASA's Johnson Space Center, where the Mission Control Center is located.

Houston's economy has a broad industrial base in energy, manufacturing, aeronautics, and transportation. Leading in health care sectors and building oilfield equipment, Houston has the second most Fortune 500 headquarters of any U.S. municipality within its city limits (after New York City).[11][12] The Port of Houston ranks first in the United States in international waterborne tonnage handled and second in total cargo tonnage handled.[13] Nicknamed the "Space City", Houston is a global city, with strengths in culture, medicine, and research. The city has a population from various ethnic and religious backgrounds and a large and growing international community. Houston is the most diverse metropolitan area in Texas and has been described as the most racially and ethnically diverse major metropolis in the U.S.[14] It is home to many cultural institutions and exhibits, which attract more than 7 million visitors a year to the Museum District. Houston has an active visual and performing arts scene in the Theater District and offers year-round resident companies in all major performing arts.[15]

History

Mexican Empire 1821–1823

United Mexican States 1823–1836

Republic of Texas 1836–1846

United States of America 1846–1861

Confederate States of America 1861–1865

United States of America 1865–present

The Allen brothers—Augustus Chapman and John Kirby—explored town sites on Buffalo Bayou and Galveston Bay. According to historian David McComb, "[T]he brothers, on August 26, 1836, bought from Elizabeth E. Parrott, wife of T.F.L. Parrott and widow of John Austin, the south half of the lower league [2,214-acre (896 ha) tract] granted to her by her late husband. They paid $5,000 total, but only $1,000 of this in cash; notes made up the remainder."[16]

The Allen brothers ran their first advertisement for Houston just four days later in the Telegraph and Texas Register, naming the notional town in honor of President Sam Houston.[10] They successfully lobbied the Republic of Texas Congress to designate Houston as the temporary capital, agreeing to provide the new government with a capital building.[17] About a dozen persons resided in the town at the beginning of 1837, but that number grew to about 1,500 by the time the Texas Congress convened in Houston for the first time that May.[10] Houston was granted incorporation on June 5, 1837, with James S. Holman becoming its first mayor.[10] In the same year, Houston became the county seat of Harrisburg County (now Harris County, Texas).[18]

In 1839, the Republic of Texas relocated its capital to Austin. The town suffered another setback that year when a yellow fever epidemic claimed about one life out of every eight residents. Yet it persisted as a commercial center, forming a symbiosis with its Gulf Coast port, Galveston. Landlocked farmers brought their produce to Houston, using Buffalo Bayou to gain access to Galveston and the Gulf of Mexico. Houston merchants profited from selling staples to farmers and shipping the farmers' produce to Galveston.[10]

The great majority of slaves in Texas came with their owners from the older slave states. Sizable numbers, however, came through the domestic slave trade. New Orleans was the center of this trade in the Deep South, but slave dealers were in Houston. Thousands of enslaved blacks lived near the city before the Civil War. Many of them near the city worked on sugar and cotton plantations, while most of those in the city limits had domestic and artisan jobs.

In 1840, the community established a chamber of commerce in part to promote shipping and navigation at the newly created port on Buffalo Bayou.[19]

By 1860, Houston had emerged as a commercial and railroad hub for the export of cotton.[18] Railroad spurs from the Texas inland converged in Houston, where they met rail lines to the ports of Galveston and Beaumont. During the American Civil War, Houston served as a headquarters for General John Magruder, who used the city as an organization point for the Battle of Galveston.[20] After the Civil War, Houston businessmen initiated efforts to widen the city's extensive system of bayous so the city could accept more commerce between downtown and the nearby port of Galveston. By 1890, Houston was the railroad center of Texas.

In 1900, after Galveston was struck by a devastating hurricane, efforts to make Houston into a viable deep-water port were accelerated.[21] The following year, the discovery of oil at the Spindletop oil field near Beaumont prompted the development of the Texas petroleum industry.[22] In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt approved a $1 million improvement project for the Houston Ship Channel. By 1910, the city's population had reached 78,800, almost doubling from a decade before. African Americans formed a large part of the city's population, numbering 23,929 people, which was nearly one-third of the residents.[23]

President Woodrow Wilson opened the deep-water Port of Houston in 1914, seven years after digging began. By 1930, Houston had become Texas' most populous city and Harris County the most populous county.[24] In 1940, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Houston's population as 77.5% white and 22.4% black.[25]

When World War II started, tonnage levels at the port decreased and shipping activities were suspended; however, the war did provide economic benefits for the city. Petrochemical refineries and manufacturing plants were constructed along the ship channel because of the demand for petroleum and synthetic rubber products by the defense industry during the war.[26] Ellington Field, initially built during World War I, was revitalized as an advanced training center for bombardiers and navigators.[27] The Brown Shipbuilding Company was founded in 1942 to build ships for the U.S. Navy during World War II. Due to the boom in defense jobs, thousands of new workers migrated to the city, both blacks and whites competing for the higher-paying jobs. President Roosevelt had established a policy of nondiscrimination for defense contractors, and blacks gained some opportunities, especially in shipbuilding, although not without resistance from whites and increasing social tensions that erupted into occasional violence. Economic gains of blacks who entered defense industries continued in the postwar years.[28]

In 1945, the M.D. Anderson Foundation formed the Texas Medical Center. After the war, Houston's economy reverted to being primarily port-driven. In 1948, the city annexed several unincorporated areas, more than doubling its size. Houston proper began to spread across the region.[10][29]

In 1950, the availability of air conditioning provided impetus for many companies to relocate to Houston, where wages were lower than those in the North; this resulted in an economic boom and produced a key shift in the city's economy toward the energy sector.[30][31]

The increased production of the expanded shipbuilding industry during World War II spurred Houston's growth,[32] as did the establishment in 1961 of NASA's "Manned Spacecraft Center" (renamed the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in 1973). This was the stimulus for the development of the city's aerospace industry. The Astrodome, nicknamed the "Eighth Wonder of the World",[33] opened in 1965 as the world's first indoor domed sports stadium.

During the late 1970s, Houston had a population boom as people from the Rust Belt states moved to Texas in large numbers.[34] The new residents came for numerous employment opportunities in the petroleum industry, created as a result of the Arab oil embargo. With the increase in professional jobs, Houston has become a destination for many college-educated persons, including African Americans in a reverse Great Migration from northern areas.

In 1997, Houstonians elected Lee P. Brown as the city's first African American mayor.[35]

In June 2001, Tropical Storm Allison dumped up to 40 inches (1,000 mm) of rain on parts of Houston, causing what was then the worst flooding in the city's history. The storm cost billions of dollars in damage and killed 20 people in Texas.[36] By December of the same year, Houston-based energy company Enron collapsed into the largest U.S. bankruptcy (at that time), a result of being investigated for off-the-books partnerships which were allegedly used to hide debt and inflate profits. The company lost no less than $70 billion.[37]

In August 2005, Houston became a shelter to more than 150,000 people from New Orleans, who evacuated from Hurricane Katrina.[38] One month later, about 2.5 million Houston-area residents evacuated when Hurricane Rita approached the Gulf Coast, leaving little damage to the Houston area. This was the largest urban evacuation in the history of the United States.[39][40] In September 2008, Houston was hit by Hurricane Ike. As many as 40% of residents refused to leave Galveston Island because they feared the type of traffic problems that had happened after Hurricane Rita.

During its recent history, Houston has flooded several times from heavy rainfall, which has been becoming increasingly common.[41] This has been exacerbated by a lack of zoning laws, which allowed unregulated building of residential homes and other structures in flood-prone areas.[42] During the floods in 2015 and 2016, each of which dropped at least a foot of rain,[43] parts of the city were covered in several inches of water.[44] Even worse flooding happened in late August 2017, when Hurricane Harvey stalled over southeastern Texas, much like Tropical Storm Allison did seventeen years earlier, causing severe flooding in the Houston area, with some areas receiving over 50 inches (1,300 mm) of rain.[45] The rainfall exceeded 50 inches in several areas locally, breaking the national record for rainfall. The damage for the Houston area is estimated at up to $125 billion U.S. dollars,[46] and it is considered to be one of the worst natural disasters in the history of the United States,[47] with the death toll exceeding 70 people. On January 31, 2018, the Houston City Council agreed to forgive large water bills thousands of households faced in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, as Houston Public Works found 6,362 homeowners' water utility bills had at least doubled.[48][49]

Geography

Houston is located 165 miles (266 km) east of Austin,[50] 112 miles (180 km) west of the Louisiana border, and 250 miles (400 km) south of Dallas.[51] The city has a total area of 627 square miles (1,620 km2); this comprises 599.59 square miles (1,552.9 km2) of land[52] and 22.3 square miles (58 km2) covered by water.[53] The Piney Woods are north of Houston. Most of Houston is located on the gulf coastal plain, and its vegetation is classified as temperate grassland and forest. Much of the city was built on forested land, marshes, swamp, or prairie and are all still visible in surrounding areas. Flat terrain and extensive greenfield development have combined to worsen flooding.[54] Downtown stands about 50 feet (15 m) above sea level,[55] and the highest point in far northwest Houston is about 125 feet (38 m) in elevation.[56][57] The city once relied on groundwater for its needs, but land subsidence forced the city to turn to ground-level water sources such as Lake Houston, Lake Conroe, and Lake Livingston.[10][58] The city owns surface water rights for 1.20 billion gallons of water a day in addition to 150 million gallons a day of groundwater.[59]

Houston has four major bayous passing through the city that accept water from the extensive drainage system. Buffalo Bayou runs through downtown and the Houston Ship Channel, and has three tributaries: White Oak Bayou, which runs through the Houston Heights community northwest of Downtown and then towards Downtown; Brays Bayou, which runs along the Texas Medical Center;[60] and Sims Bayou, which runs through the south of Houston and downtown Houston. The ship channel continues past Galveston and then into the Gulf of Mexico.[26]

Geology

Houston is a flat marshy area where an extensive drainage system has been built. The adjoining prairie land drains into the city which is prone to flooding.[61] Underpinning Houston's land surface are unconsolidated clays, clay shales, and poorly cemented sands up to several miles deep. The region's geology developed from river deposits formed from the erosion of the Rocky Mountains. These sediments consist of a series of sands and clays deposited on decaying organic marine matter, that over time, transformed into oil and natural gas. Beneath the layers of sediment is a water-deposited layer of halite, a rock salt. The porous layers were compressed over time and forced upward. As it pushed upward, the salt dragged surrounding sediments into salt dome formations, often trapping oil and gas that seeped from the surrounding porous sands. The thick, rich, sometimes black, surface soil is suitable for rice farming in suburban outskirts where the city continues to grow.[62][63]

The Houston area has over 150 active faults (estimated to be 300 active faults) with an aggregate length of up to 310 miles (500 km),[64][65][66] including the Long Point–Eureka Heights fault system which runs through the center of the city. No significant historically recorded earthquakes have occurred in Houston, but researchers do not discount the possibility of such quakes having occurred in the deeper past, nor occurring in the future. Land in some areas southeast of Houston is sinking because water has been pumped out of the ground for many years. It may be associated with slip along the faults; however, the slippage is slow and not considered an earthquake, where stationary faults must slip suddenly enough to create seismic waves.[67] These faults also tend to move at a smooth rate in what is termed "fault creep",[58] which further reduces the risk of an earthquake.

Climate

.jpg)

Houston's climate is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa in the Köppen climate classification system), typical of the Southern United States. The city experiences very hot, long, and humid summers, and mild winters. While not located in Tornado Alley, like much of northern Texas, spring supercell thunderstorms sometimes bring tornadoes to the area.

Prevailing winds are from the south and southeast during most of the year, which bring heat and moisture from the nearby Gulf of Mexico and Galveston Bay.[68]

During the summer, temperatures in Houston commonly reach over 90 °F (32 °C). The city reaches or surpasses this temperature on an average of 106.5 days per year, including a majority of days from June to September; additionally, an average of 4.6 days per year exceed 100 °F (38 °C).[69] Houston's characteristic subtropical humidity often results in a higher apparent temperature, and summer mornings average over 90% relative humidity.[70] Air conditioning is ubiquitous in Houston; in 1981, annual spending on electricity for interior cooling exceeded $600 million (equivalent to $1.62 billion in 2017), and by the late 1990s, approximately 90% of Houston homes featured air conditioning systems.[71][72] The record highest temperature recorded in Houston is 109 °F (43 °C) at Bush Intercontinental Airport, during September 4, 2000, and again on August 28, 2011.[69]

Houston has mild winters. In January, the normal mean temperature at George Bush Intercontinental Airport is 53.1 °F (12 °C), with an average of 13 days per year with a low at or below 32 °F (0 °C). Twenty-first century snow events in Houston include a storm on December 24, 2004, which saw 1 inch (3 cm) of snow accumulate in parts of the metro area,[73] and an event on December 7, 2017, which precipitated 0.7 inches (2 cm) of snowfall.[74][75] Snowfalls of at least 1.0 inch (2.5 cm) on both December 10, 2008, and December 4, 2009, marked the first time measurable snowfall had occurred in two consecutive years in the city's recorded history. Overall, Houston has seen measurable snowfall 38 times between 1895 and 2018. On February 14 and 15, 1895, Houston received 20 inches (51 cm) of snow, its largest snowfall from one storm on record.[76] The coldest temperature officially recorded in Houston was 5 °F (−15 °C) on January 18, 1930.[69]

Houston generally receives ample rainfall, averaging about 49.8 in (1,260 mm) annually based on records between 1981 and 2010. Many parts of the city have a high risk of localized flooding due to flat topography,[77] ubiquitous low-permeability clay-silt prairie soils,[78] and inadequate infrastructure.[77] During the mid-2010s, Greater Houston experienced consecutive major flood events in 2015 ("Memorial Day"),[79] 2016 ("Tax Day"),[80] and 2017 (Hurricane Harvey).[81] Overall, there have been more casualties and property loss from floods in Houston than in any other locality in the United States.[82]

Houston has excessive ozone levels and is routinely ranked among the most ozone-polluted cities in the United States.[83] Ground-level ozone, or smog, is Houston's predominant air pollution problem, with the American Lung Association rating the metropolitan area's ozone level twelfth on the "Most Polluted Cities by Ozone" in 2017, after major cities such as Los Angeles, Phoenix, New York City and Denver.[84] The industries located along the ship channel are a major cause of the city's air pollution.[85] The rankings are in terms of peak-based standards, focusing strictly on the worst days of the year; the average ozone levels in Houston are lower than what is seen in most other areas of the country, as dominant winds ensure clean, marine air from the Gulf.[86]

| Climate data for Houston (Intercontinental Airport), 1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1888–present[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

109 (43) |

109 (43) |

99 (37) |

89 (32) |

85 (29) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.4 (25.8) |

80.8 (27.1) |

84.8 (29.3) |

88.9 (31.6) |

93.6 (34.2) |

97.0 (36.1) |

98.4 (36.9) |

100.4 (38) |

96.9 (36.1) |

91.8 (33.2) |

85.0 (29.4) |

80.0 (26.7) |

101.0 (38.3) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 62.9 (17.2) |

66.3 (19.1) |

73.0 (22.8) |

79.6 (26.4) |

86.3 (30.2) |

91.4 (33) |

93.7 (34.3) |

94.5 (34.7) |

89.7 (32.1) |

82.0 (27.8) |

72.5 (22.5) |

64.3 (17.9) |

79.7 (26.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.1 (11.7) |

56.4 (13.6) |

62.7 (17.1) |

69.5 (20.8) |

76.9 (24.9) |

82.4 (28) |

84.4 (29.1) |

84.6 (29.2) |

79.8 (26.6) |

71.5 (21.9) |

62.3 (16.8) |

54.4 (12.4) |

69.9 (21.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 43.2 (6.2) |

46.5 (8.1) |

52.5 (11.4) |

59.4 (15.2) |

67.6 (19.8) |

73.5 (23.1) |

75.1 (23.9) |

74.8 (23.8) |

69.8 (21) |

60.9 (16.1) |

52.1 (11.2) |

44.6 (7) |

60.0 (15.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 26.7 (−2.9) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

34.0 (1.1) |

42.0 (5.6) |

53.3 (11.8) |

65.2 (18.4) |

69.4 (20.8) |

68.6 (20.3) |

55.7 (13.2) |

43.4 (6.3) |

34.5 (1.4) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 5 (−15) |

6 (−14) |

21 (−6) |

31 (−1) |

42 (6) |

52 (11) |

62 (17) |

54 (12) |

45 (7) |

29 (−2) |

19 (−7) |

7 (−14) |

5 (−15) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.38 (85.9) |

3.20 (81.3) |

3.41 (86.6) |

3.31 (84.1) |

5.09 (129.3) |

5.93 (150.6) |

3.79 (96.3) |

3.76 (95.5) |

4.12 (104.6) |

5.70 (144.8) |

4.34 (110.2) |

3.74 (95) |

49.77 (1,264.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.6 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 8.0 | 10.6 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 9.5 | 104.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.7 | 73.4 | 72.7 | 73.1 | 75.0 | 74.6 | 74.4 | 75.1 | 76.8 | 75.4 | 76.0 | 75.5 | 74.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 143.4 | 155.0 | 192.5 | 209.8 | 249.2 | 281.3 | 293.9 | 270.5 | 236.5 | 228.8 | 168.3 | 148.7 | 2,577.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 44 | 50 | 52 | 54 | 59 | 67 | 68 | 66 | 64 | 64 | 53 | 47 | 58 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity 1969–1990, sun 1961–1990)[69][88][89] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Houston (William P. Hobby Airport), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1941–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

87 (31) |

96 (36) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

96 (36) |

90 (32) |

84 (29) |

108 (42) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.0 (17.2) |

66.0 (18.9) |

72.4 (22.4) |

78.8 (26) |

85.4 (29.7) |

90.1 (32.3) |

92.1 (33.4) |

92.6 (33.7) |

88.4 (31.3) |

81.2 (27.3) |

72.4 (22.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

78.9 (26.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 54.1 (12.3) |

57.3 (14.1) |

63.3 (17.4) |

69.8 (21) |

77.0 (25) |

82.0 (27.8) |

83.8 (28.8) |

84.2 (29) |

80.1 (26.7) |

72.1 (22.3) |

63.2 (17.3) |

55.6 (13.1) |

70.3 (21.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 45.1 (7.3) |

48.5 (9.2) |

54.3 (12.4) |

60.9 (16.1) |

68.7 (20.4) |

73.9 (23.3) |

75.5 (24.2) |

75.7 (24.3) |

71.7 (22.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

53.9 (12.2) |

46.7 (8.2) |

61.5 (16.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 10 (−12) |

14 (−10) |

22 (−6) |

36 (2) |

44 (7) |

56 (13) |

64 (18) |

66 (19) |

50 (10) |

33 (1) |

25 (−4) |

9 (−13) |

9 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.87 (98.3) |

3.21 (81.5) |

3.20 (81.3) |

3.25 (82.6) |

4.75 (120.7) |

7.10 (180.3) |

4.66 (118.4) |

5.06 (128.5) |

5.21 (132.3) |

5.99 (152.1) |

4.32 (109.7) |

4.03 (102.4) |

54.65 (1,388.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.2 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 7.3 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 9.1 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 103.7 |

| Source: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[69] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Houston was incorporated in 1837 and adopted a ward system of representation shortly afterward in 1840.[90] The six original wards of Houston are the progenitors of the 11 modern-day geographically-oriented Houston City Council districts, though the city abandoned the ward system in 1905 in favor of a commission government, and, later, the existing mayor–council government.

Locations in Houston are generally classified as either being inside or outside the Interstate 610 loop. The "Inner Loop" encompasses a 97-square-mile (250 km2) area which includes Downtown, pre–World War II residential neighborhoods and streetcar suburbs, and newer high-density apartment and townhouse developments.[91] Outside the loop, the city's typology is more suburban, though many major business districts—such as Uptown, Westchase, and the Energy Corridor—lie well outside the urban core. In addition to Interstate 610, two additional loop highways encircle the city: Beltway 8, with a radius of approximately 10 miles (16 km) from Downtown, and State Highway 99 (the Grand Parkway), with a radius of 25 miles (40 km). Approximately 470,000 people live within the Interstate 610 loop, while 1.65 million live between Interstate 610 and Beltway 8 and 2.25 million live within Harris County outside Beltway 8.[92]

Though Houston is the largest city in the United States without formal zoning regulations, it has developed similarly to other Sun Belt cities because the city's land use regulations and legal covenants have played a similar role.[93][94] Regulations include mandatory lot size for single-family houses and requirements that parking be available to tenants and customers. Such restrictions have had mixed results. Though some have blamed the city's low density, urban sprawl, and lack of pedestrian-friendliness on these policies, the city's land use has also been credited with having significant affordable housing, sparing Houston the worst effects of the 2008 real estate crisis.[94][95] The city issued 42,697 building permits in 2008 and was ranked first in the list of healthiest housing markets for 2009.[96]

Voters rejected efforts to have separate residential and commercial land-use districts in 1948, 1962, and 1993. Consequently, rather than a single central business district as the center of the city's employment, multiple districts have grown throughout the city in addition to Downtown, which include Uptown, Texas Medical Center, Midtown, Greenway Plaza, Memorial City, Energy Corridor, Westchase, and Greenspoint.

Architecture

Houston has the fourth-tallest skyline in North America (after New York City, Chicago, and Toronto) and 36th-tallest in the world as of 2018.[97] A seven-mile (11 km) system of tunnels and skywalks links downtown buildings containing shops and restaurants, enabling pedestrians to avoid summer heat and rain while walking between buildings.

In the 1960s, Downtown Houston consisted of a collection of midrise office structures. Downtown was on the threshold of an energy industry–led boom in 1970. A succession of skyscrapers was built throughout the 1970s—many by real estate developer Gerald D. Hines—culminating with Houston's tallest skyscraper, the 75-floor, 1,002-foot (305 m)-tall JPMorgan Chase Tower (formerly the Texas Commerce Tower), completed in 1982. It is the tallest structure in Texas, 15th tallest building in the United States, and the 85th-tallest skyscraper in the world, based on highest architectural feature. In 1983, the 71-floor, 992-foot (302 m)-tall Wells Fargo Plaza (formerly Allied Bank Plaza) was completed, becoming the second-tallest building in Houston and Texas. Based on highest architectural feature, it is the 17th-tallest in the United States and the 95th-tallest in the world. In 2007, Downtown had over 43 million square feet (4,000,000 m²) of office space.[98]

Centered on Post Oak Boulevard and Westheimer Road, the Uptown District boomed during the 1970s and early 1980s when a collection of midrise office buildings, hotels, and retail developments appeared along Interstate 610 West. Uptown became one of the most prominent instances of an edge city. The tallest building in Uptown is the 64-floor, 901-foot (275 m)-tall, Philip Johnson and John Burgee designed landmark Williams Tower (known as the Transco Tower until 1999). At the time of construction, it was believed to be the world's tallest skyscraper outside a central business district. The new 20-story Skanska building[99] and BBVA Compass Plaza[100] are the newest office buildings built in Uptown after 30 years. The Uptown District is also home to buildings designed by noted architects I. M. Pei, César Pelli, and Philip Johnson. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a mini-boom of midrise and highrise residential tower construction occurred, with several over 30 stories tall.[101][102][103] Since 2000 more than 30 high-rise buildings have gone up in Houston; all told, 72 high-rises tower over the city, which adds up to about 8,300 units.[104] In 2002, Uptown had more than 23 million square feet (2,100,000 m²) of office space with 16 million square feet (1,500,000 m²) of class A office space.[105]

The Niels Esperson Building stood as the tallest building in Houston from 1927 to 1929.

The Niels Esperson Building stood as the tallest building in Houston from 1927 to 1929.- The JPMorgan Chase Tower is the tallest building in Texas and the tallest 5-sided building in the world.

The Williams Tower is the tallest building in the US outside a central business district.

The Williams Tower is the tallest building in the US outside a central business district. The Bank of America Center by Philip Johnson is an example of postmodern architecture.

The Bank of America Center by Philip Johnson is an example of postmodern architecture.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,396 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,845 | 102.2% | |

| 1870 | 9,382 | 93.6% | |

| 1880 | 16,513 | 76.0% | |

| 1890 | 27,557 | 66.9% | |

| 1900 | 44,633 | 62.0% | |

| 1910 | 78,800 | 76.6% | |

| 1920 | 138,276 | 75.5% | |

| 1930 | 292,352 | 111.4% | |

| 1940 | 384,514 | 31.5% | |

| 1950 | 596,163 | 55.0% | |

| 1960 | 938,219 | 57.4% | |

| 1970 | 1,232,802 | 31.4% | |

| 1980 | 1,595,138 | 29.4% | |

| 1990 | 1,630,553 | 2.2% | |

| 2000 | 1,953,631 | 19.8% | |

| 2010 | 2,100,263 | 7.5% | |

| Est. 2017 | 2,312,717 | [2] | 10.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census 2011 estimate | |||

| Racial composition | 2010[106] | 2000[107] | 1990[25] | 1970[25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 50.5% | 49.3% | 52.7% | 73.4% |

| —Non-Hispanic whites | 25.6% | 30.8% | 40.6% | 62.4%[108] |

| Black or African American | 23.7% | 25.3% | 28.1% | 25.7%,[109] |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 43.7% | 37.4% | 27.6% | 11.3%[108] |

| Asian | 6.0% | 5.3% | 4.1% | 0.4% |

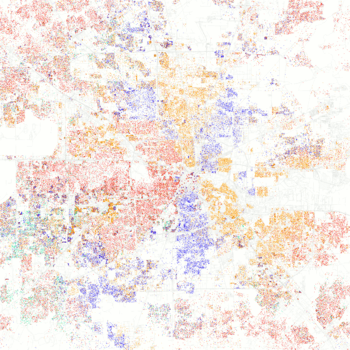

The Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research, a think tank, has described Greater Houston as "one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse metropolitan areas in the country."[110] A 2012 Kinder Institute report found that, based on the evenness of population distribution between the four major racial groups in the United States (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian), Greater Houston was the most ethnically diverse metropolitan area in the United States, ahead of New York City.[111] In 2017, non-Hispanic whites made up 38% of the population of the Houston metropolitan area, Hispanics 36%, African-Americans 17%, and Asians 9%.[112]

Houston's multiculturalism, fueled by large waves of immigrants, has been attributed to its relatively low cost of living, strong job market, proximity to Latin America, and role as a hub for refugee resettlement.[113][114] At least 145 languages are spoken by city residents.[115] Greater Houston is one of the youngest metropolitan areas in the nation, with an estimated average age of 33.5 in 2014, compared with the national average of 37.4;[116] the city's youthfulness has been attributed to an influx of Hispanic and Asian immigrants into Texas.[117] As of 2017, an estimated 600,000 undocumented immigrants reside in the Houston area,[118] comprising nearly 9% of the metropolitan population.[119]

Compared with its metropolitan area, the city of Houston's population has a higher proportion of minorities. According to the 2010 Census, whites made up 51% of the city of Houston's population; 26% of the total population was non-Hispanic whites.[106] Blacks or African Americans made up 25% of Houston's population, American Indians made up 0.7% of the population, Asians made up 6%[106] (1.7% Vietnamese, 1.3% Chinese, 1.3% Indian, 0.9% Pakistani, 0.4% Filipino, 0.3% Korean, 0.1% Japanese) and Pacific Islanders made up 0.1%. Individuals from some other race made up 15.2% of the city's population, of which 0.2% were non-Hispanic. Individuals from two or more races made up 3.3% of the city.[106]

At the 2000 Census, 1,953,631 people inhabited the city, and the population density was 3,371.7 people per square mile (1,301.8/km²). The racial makeup of the city in 2000 was 49.3% White, 25.3% African American, 6.3% Asian, 0.7% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 16.5% from some other race, and 3.1% from two or more races. In addition, Hispanics made up 37.4% of Houston's population in 2000, while non-Hispanic Whites made up 30.8%.[109] The proportion of non-Hispanic whites in Houston has decreased significantly since 1970, when it was 62.4%.[25]

The median income for a household in the city was $37,000, and for a family was $40,000. Males had a median income of $32,000 versus $27,000 for females. The per capita income was $20,000. About 19% of the population and 16% of families were below the poverty line. Of the total population, 26% of those under the age of 18 and 14% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, 73% of the population of the Houston area identified themselves as Christians, about 50% of whom claimed Protestant affiliations and about 19% claimed Roman Catholic affiliations. Nationwide, about 71% of respondents identified as Christians. About 20% of Houston-area residents claimed no religious affiliation, compared to about 23% nationwide.[120] The same study says that area residents identifying with other religions (including Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, and Hinduism) collectively make up about 7% of the area population.[120]

Economy

| Top publicly traded companies in Houston for 2018 | ||

| US | Company | |

|---|---|---|

| 28 | Phillips 66 | |

| 54 | Sysco | |

| 95 | ConocoPhilips | |

| 105 | Enterprise Products Partners | |

| 115 | Plains GP Holdings | |

| 146 | Halliburton | |

| 202 | Waste Management | |

| 218 | Kinder Morgan | |

| 220 | Occidental Petroleum | |

| 270 | EOG Resources | |

| 273 | Group 1 Automotive | |

| 308 | CenterPoint Energy | |

| 316 | Quanta Services | |

| 334 | Targa Resources | |

| 336 | Calpine | |

| 352 | Westlake Chemical | |

| 388 | National Oilwell Varco | |

| 438 | Apache Corporation | |

| 489 | Cheniere Energy | |

| Notes | ||

| Rankings for fiscal year ended January 31, 2018 | ||

| Energy and oil (15 companies) | ||

| Source: Fortune[121] | ||

Houston is recognized worldwide for its energy industry—particularly for oil and natural gas—as well as for biomedical research and aeronautics. Renewable energy sources—wind and solar—are also growing economic bases in the city.[122][123] The Houston Ship Channel is also a large part of Houston's economic base. Because of these strengths, Houston is designated as a global city by the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network and global management consulting firm A.T. Kearney.[12] The Houston area is the top U.S. market for exports, surpassing New York City in 2013, according to data released by the U.S. Department of Commerce's International Trade Administration. In 2012, the Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land area recorded $110.3 billion in merchandise exports.[124] Petroleum products, chemicals, and oil and gas extraction equipment accounted for roughly two-thirds of the metropolitan area's exports last year. The top three destinations for exports were Mexico, Canada, and Brazil.[125]

The Houston area is a leading center for building oilfield equipment.[126] Much of its success as a petrochemical complex is due to its busy ship channel, the Port of Houston.[127] In the United States, the port ranks first in international commerce and 10th among the largest ports in the world.[13][128] Unlike most places, high oil and gasoline prices are beneficial for Houston's economy, as many of its residents are employed in the energy industry.[129] Houston is the beginning or end point of numerous oil, gas, and products pipelines.[130]

The Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land MSA's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016 was $478 billion, making it the sixth-largest of any metropolitan area in the United States and larger than Iran's, Colombia's, or the United Arab Emirates' GDP.[131] Only 27 countries other than the United States have a gross domestic product exceeding Houston's regional gross area product (GAP).[132] In 2010, mining (which consists almost entirely of exploration and production of oil and gas in Houston) accounted for 26.3% of Houston's GAP up sharply in response to high energy prices and a decreased worldwide surplus of oil production capacity, followed by engineering services, health services, and manufacturing.[133]

The University of Houston System's annual impact on the Houston area's economy equates to that of a major corporation: $1.1 billion in new funds attracted annually to the Houston area, $3.13 billion in total economic benefit, and 24,000 local jobs generated.[134][135] This is in addition to the 12,500 new graduates the U.H. System produces every year who enter the workforce in Houston and throughout the state of Texas. These degree-holders tend to stay in Houston. After five years, 80.5% of graduates are still living and working in the region.[135]

In 2006, the Houston metropolitan area ranked first in Texas and third in the U.S. within the category of "Best Places for Business and Careers" by Forbes magazine.[136] Foreign governments have established 92 consular offices in Houston's metropolitan area, the third-highest in the nation.[137] Forty foreign governments maintain trade and commercial offices here with 23 active foreign chambers of commerce and trade associations.[138] Twenty-five foreign banks representing 13 nations operate in Houston, providing financial assistance to the international community.[139]

In 2008, Houston received top ranking on Kiplinger's Personal Finance Best Cities of 2008 list, which ranks cities on their local economy, employment opportunities, reasonable living costs, and quality of life.[140] The city ranked fourth for highest increase in the local technological innovation over the preceding 15 years, according to Forbes magazine.[141] In the same year, the city ranked second on the annual Fortune 500 list of company headquarters,[142] first for Forbes magazine's Best Cities for College Graduates,[143] and first on their list of Best Cities to Buy a Home.[144] In 2010, the city was rated the best city for shopping, according to Forbes.[145]

In 2012, the city was ranked number one for paycheck worth by Forbes and in late May 2013, Houston was identified as America's top city for employment creation.[146][147]

In 2013, Houston was identified as the number one U.S. city for job creation by the U.S. Bureau of Statistics after it was not only the first major city to regain all the jobs lost in the preceding economic downturn, but also after the crash, more than two jobs were added for every one lost. Economist and vice president of research at the Greater Houston Partnership Patrick Jankowski attributed Houston's success to the ability of the region's real estate and energy industries to learn from historical mistakes. Furthermore, Jankowski stated that "more than 100 foreign-owned companies relocated, expanded or started new businesses in Houston" between 2008 and 2010, and this openness to external business boosted job creation during a period when domestic demand was problematically low.[147] Also in 2013, Houston again appeared on Forbes' list of Best Places for Business and Careers.[148]

Culture

Located in the American South, Houston is a diverse city with a large and growing international community.[149] The Houston Metropolitan area is home to an estimated 1.1 million (21.4 percent) residents who were born outside the United States, with nearly two-thirds of the area's foreign-born population from south of the United States–Mexico border.[150] Additionally, more than one in five foreign-born residents are from Asia.[150] The city is home to the nation's third-largest concentration of consular offices, representing 86 countries.[151]

Many annual events celebrate the diverse cultures of Houston. The largest and longest-running is the annual Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, held over 20 days from early to late March, and is the largest annual livestock show and rodeo in the world.[152] Another large celebration is the annual night-time Houston Gay Pride Parade, held at the end of June.[153] Other notable annual events include the Houston Greek Festival,[154] Art Car Parade, the Houston Auto Show, the Houston International Festival,[155] and the Bayou City Art Festival, which is considered to be one of the top five art festivals in the United States.[156][157]

Houston received the official nickname of "Space City" in 1967 because it is the location of NASA's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Other nicknames often used by locals include "Bayou City", "Clutch City", "Crush City", "Magnolia City", and "H-Town".

Arts and theater

The Houston Theater District, located in downtown, is home to nine major performing arts organizations and six performance halls. It is the second-largest concentration of theater seats in a downtown area in the United States.[158][159][160] Houston is one of few United States cities with permanent, professional, resident companies in all major performing arts disciplines: opera (Houston Grand Opera), ballet (Houston Ballet), music (Houston Symphony Orchestra), and theater (The Alley Theatre, Theatre Under the Stars).[15][161] Houston is also home to folk artists, art groups and various small progressive arts organizations.[162] Houston attracts many touring Broadway acts, concerts, shows, and exhibitions for a variety of interests.[163] Facilities in the Theater District include the Jones Hall—home of the Houston Symphony Orchestra and Society for the Performing Arts—and the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts.

The Museum District's cultural institutions and exhibits attract more than 7 million visitors a year.[164][165] Notable facilities include The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Museum of Natural Science, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the Station Museum of Contemporary Art, Holocaust Museum Houston, and the Houston Zoo.[166][167][168] Located near the Museum District are The Menil Collection, Rothko Chapel, and the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum.

Bayou Bend is a 14-acre (5.7 ha) facility of the Museum of Fine Arts that houses one of America's most prominent collections of decorative art, paintings, and furniture. Bayou Bend is the former home of Houston philanthropist Ima Hogg.[169]

The National Museum of Funeral History is located in Houston near the George Bush Intercontinental Airport. The museum houses the original Popemobile used by Pope John Paul II in the 1980s along with numerous hearses, embalming displays, and information on famous funerals.

Venues across Houston regularly host local and touring rock, blues, country, dubstep, and Tejano musical acts. While Houston has never been widely known for its music scene,[170] Houston hip-hop has become a significant, independent music scene that is influential nationwide.[171]

Tourism and recreation

The Theater District is a 17-block area in the center of downtown Houston that is home to the Bayou Place entertainment complex, restaurants, movies, plazas, and parks. Bayou Place is a large multilevel building containing full-service restaurants, bars, live music, billiards, and Sundance Cinema. The Bayou Music Center stages live concerts, stage plays, and stand-up comedy.

Space Center Houston is the official visitors' center of NASA's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. The Space Center has many interactive exhibits including moon rocks, a shuttle simulator, and presentations about the history of NASA's manned space flight program. Other tourist attractions include the Galleria (Texas' largest shopping mall, located in the Uptown District), Old Market Square, the Downtown Aquarium, and Sam Houston Race Park.

Of worthy mention are Houston's current Chinatown and the Mahatma Gandhi District. Both areas offer a picturesque view of Houston's multicultural makeup. Restaurants, bakeries, traditional-clothing boutiques, and specialty shops can be found in both areas.

Houston is home to 337 parks, including Hermann Park, Terry Hershey Park, Lake Houston Park, Memorial Park, Tranquility Park, Sesquicentennial Park, Discovery Green, Buffalo Bayou Park and Sam Houston Park. Within Hermann Park are the Houston Zoo and the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Sam Houston Park contains restored and reconstructed homes which were originally built between 1823 and 1905.[172] A proposal has been made to open the city's first botanic garden at Herman Brown Park.[173]

Of the 10 most populous U.S. cities, Houston has the most total area of parks and green space, 56,405 acres (228 km2).[174] The city also has over 200 additional green spaces—totaling over 19,600 acres (79 km2) that are managed by the city—including the Houston Arboretum and Nature Center. The Lee and Joe Jamail Skatepark is a public skatepark owned and operated by the city of Houston, and is one of the largest skateparks in Texas consisting of a 30,000-ft2 (2,800 m2)in-ground facility. The Gerald D. Hines Waterwall Park—located in the Uptown District of the city—serves as a popular tourist attraction and for weddings and various celebrations. A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Houston the 23rd most walkable of the 50 largest cities in the United States.[175] Wet'n'Wild SplashTown is a water park located north of Houston.

The Bayport Cruise Terminal on the Houston Ship Channel is port of call for both Princess Cruises and Norwegian Cruise Line.[176]

Sports

Houston has sports teams for every major professional league except the National Hockey League. The Houston Astros are a Major League Baseball expansion team formed in 1962 (known as the "Colt .45s" until 1965) that won the World Series in 2017 and previously appeared in 2005. It is the only MLB team to have won pennants in both modern leagues.[177] The Houston Rockets are a National Basketball Association franchise based in the city since 1971. They have won two NBA Championships: in 1994 and 1995 under star players Hakeem Olajuwon, Otis Thorpe, Clyde Drexler, Vernon Maxwell, and Kenny Smith.[178] The Houston Texans are a National Football League expansion team formed in 2002. The Houston Dynamo is a Major League Soccer franchise that has been based in Houston since 2006, winning two MLS Cup titles in 2006 and 2007. The Houston Dash team plays in the National Women's Soccer League.[179] The Houston SaberCats are a Rugby team that plays in the Major League Rugby.[180] Minute Maid Park (home of the Astros) and Toyota Center (home of the Rockets), are located in downtown Houston. Houston has the NFL's first retractable-roof stadium with natural grass, NRG Stadium (home of the Texans).[181] Minute Maid Park is also a retractable-roof stadium. Toyota Center also has the largest screen for an indoor arena in the United States built to coincide with the arena's hosting of the 2013 NBA All-Star Game.[182] BBVA Compass Stadium is a soccer-specific stadium for the Houston Dynamo, the Texas Southern Tigers football team, and Houston Dash, located in East Downtown. Aveva Stadium (home of the SaberCats) is located in south Houston. In addition, NRG Astrodome was the first indoor stadium in the world, built in 1965.[183] Other sports facilities include Hofheinz Pavilion (Houston Cougars basketball), Rice Stadium (Rice Owls football), and Reliant Arena. TDECU Stadium is where the University of Houston Houston Cougars football team plays.[184] Houston has hosted several major sports events: the 1968, 1986 and 2004 Major League Baseball All-Star Games; the 1989, 2006 and 2013 NBA All-Star Games; Super Bowl VIII and Super Bowl XXXVIII, as well as hosting the 1981, 1986, 1994 and 1995 NBA Finals, winning the latter two, and co-hosting the 2005 World Series and 2017 World Series, winning the latter. NRG Stadium hosted Super Bowl LI on February 5, 2017.[185]

The city has hosted several major professional and college sporting events, including the annual Houston Open golf tournament. Houston hosts the annual Houston College Classic baseball tournament every February and the Texas Bowl in December.[186]

The Grand Prix of Houston, an annual auto race on the IndyCar Series circuit is held on a 1.7-mile temporary street circuit in Reliant Park. The October 2013 event was held using a tweaked version of the 2006–2007 course.[187] The event has a 5-year race contract through 2017 with IndyCar.[188] In motorcycling, the Astrodome hosted an AMA Supercross Championship round from 1974 to 2003 and the NRG Stadium since 2003.

Government and politics

The city of Houston has a strong mayoral form of municipal government.[189] Houston is a home rule city and all municipal elections in the state of Texas are nonpartisan.[189][190] The city's elected officials are the mayor, city controller and 16 members of the Houston City Council.[191] The current mayor of Houston is Sylvester Turner, a Democrat elected on a nonpartisan ballot. Houston's mayor serves as the city's chief administrator, executive officer, and official representative, and is responsible for the general management of the city and for seeing that all laws and ordinances are enforced.[192]

The original city council line-up of 14 members (nine district-based and five at-large positions) was based on a U.S. Justice Department mandate which took effect in 1979.[193] At-large council members represent the entire city.[191] Under the city charter, once the population in the city limits exceeded 2.1 million residents, two additional districts were to be added.[194] The city of Houston's official 2010 census count was 600 shy of the required number; however, as the city was expected to grow beyond 2.1 million shortly thereafter, the two additional districts were added for, and the positions filled during, the August 2011 elections.

The city controller is elected independently of the mayor and council. The controller's duties are to certify available funds prior to committing such funds and processing disbursements. The city's fiscal year begins on July 1 and ends on June 30. Chris Brown is the city controller, serving his first term as of January 2016.

As the result of a 2015 referendum in Houston, a mayor is elected for a four-year term, and can be elected to as many as two consecutive terms.[195] The term limits were spearheaded in 1991 by conservative political activist Clymer Wright.[196] During 1991–2015, the city controller and city council members were subjected to a two-year, three-term limitation – the 2015 referendum amended term limits to two four-year terms. As of 2017 some councilmembers who served two terms and won a final term will have served eight years in office, whereas a freshman councilmember who won a position in 2013 can serve up to two additional terms under the previous term limit law – a select few will have at least 10 years of incumbency once their term expires.

Houston is considered to be a politically divided city whose balance of power often sways between Republicans and Democrats. Much of the city's wealthier areas vote Republican while the city's working class and minority areas vote Democratic. According to the 2005 Houston Area Survey, 68 percent of non-Hispanic whites in Harris County are declared or favor Republicans while 89 percent of non-Hispanic blacks in the area are declared or favor Democrats. About 62 percent of Hispanics (of any race) in the area are declared or favor Democrats.[197] The city has often been known to be the most politically diverse city in Texas, a state known for being generally conservative.[197] As a result, the city is often a contested area in statewide elections.[197] In 2009, Houston became the first US city with a population over 1 million citizens to elect a gay mayor, by electing Annise Parker.

Crime

Houston had 303 homicides in 2015 and 302 homicides in 2016. Officials predicted there would be 323 homicides in 2016. Instead, there was no increase in Houston's homicide rate between 2015 and 2016.[198]

Houston's murder rate ranked 46th of U.S. cities with a population over 250,000 in 2005 (per capita rate of 16.3 murders per 100,000 population).[199] In 2010, the city's murder rate (per capita rate of 11.8 murders per 100,000 population) was ranked sixth among U.S. cities with a population of over 750,000 (behind New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Dallas, and Philadelphia)[200] according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Murders fell by 37 percent from January to June 2011, compared with the same period in 2010. Houston's total crime rate including violent and nonviolent crimes decreased by 11 percent.[201] The FBI's Uniform Crime Report (UCR) indicates a downward trend of violent crime in Houston over the ten- and twenty-year periods ending in 2016, which is consistent with national trends. This trend toward lower rates of violent crime in Houston includes the murder rate, though it had seen a four-year uptick that lasted through 2015. Houston's violent crime rate is 8.6% percent higher in 2016 from the previous year. However, from 2006 to 2016, violent crime is still down 12 percent in Houston.[202]

Houston is a significant hub for trafficking of cocaine, cannabis, heroin, MDMA, and methamphetamine due to its size and proximity to major illegal drug exporting nations.[203] Houston is one of the country's largest hubs for human trafficking.[204]

In the early 1970s, Houston, Pasadena and several coastal towns were the site of the Houston mass murders, which at the time were the deadliest case of serial killing in American history.[205][206]

Education

Seventeen school districts exist within the city of Houston. The Houston Independent School District (HISD) is the seventh-largest school district in the United States and the largest in Texas.[207] HISD has 112 campuses that serve as magnet or vanguard schools—specializing in such disciplines as health professions, visual and performing arts, and the sciences. There are also many charter schools that are run separately from school districts. In addition, some public school districts also have their own charter schools.

The Houston area encompasses more than 300 private schools,[208][209][210] many of which are accredited by Texas Private School Accreditation Commission recognized agencies. The Houston Area independent schools offer education from a variety of different religious as well as secular viewpoints.[211] The Houston area Catholic schools are operated by the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston.

Colleges and universities

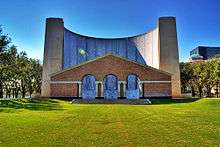

Four distinct state universities are located in Houston. The University of Houston (UH) is a nationally recognized tier one research university and is the flagship institution of the University of Houston System.[212][213][214] The third-largest university in Texas, the University of Houston has nearly 44,000 students on its 667-acre (270-hectare) campus in the Third Ward.[215] The University of Houston–Clear Lake and the University of Houston–Downtown are stand-alone universities within the University of Houston System; they are not branch campuses of the University of Houston. Slightly west of the University of Houston is Texas Southern University (TSU), one of the largest and most comprehensive historically black universities in the United States with approximately 10,000 students. Texas Southern University was the first state university in Houston, founded in 1927.[216]

Several private institutions of higher learning are located within the city. Rice University, the most selective university in Texas and one of the most selective in the United States,[217] is a private, secular institution with a high level of research activity.[218] Founded in 1912, Rice's historic, heavily wooded 300-acre (120-hectare) campus, located adjacent to Hermann Park and the Texas Medical Center, hosts approximately 4,000 undergraduate and 3,000 post-graduate students. To the north in Neartown, the University of St. Thomas, founded in 1947, is Houston's only Catholic university. St. Thomas provides a liberal arts curriculum for roughly 3,000 students at its historic 19-block campus along Montrose Boulevard. In southwest Houston, Houston Baptist University (HBU), founded in 1960, offers bachelor's and graduate degrees at its Sharpstown campus. The school is affiliated with the Baptist General Convention of Texas and has a student population of approximately 3,000.

Three community college districts have campuses in and around Houston. The Houston Community College System (HCC) serves most of Houston proper; its main campus and headquarters are located in Midtown. Suburban northern and western parts of the metropolitan area are served by various campuses of the Lone Star College System, while the southeastern portion of Houston is served by San Jacinto College, and a northeastern portion is served by Lee College.[219] The Houston Community College and Lone Star College systems are among the 10 largest institutions of higher learning in the United States.

Houston also hosts a number of graduate schools in law and healthcare. The University of Houston Law Center and Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University are public, ABA-accredited law schools, while the South Texas College of Law, located in Downtown, serves as a private, independent alternative. The Texas Medical Center is home to a high density of health professions schools, including two medical schools: McGovern Medical School, part of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and Baylor College of Medicine, a selective private institution. Prairie View A&M University's nursing school is located in the Texas Medical Center. Additionally, both Texas Southern University and the University of Houston have pharmacy schools, and the University of Houston hosts a college of optometry.

Texas Southern University, located in the Third Ward, is the first public institution of higher education in Houston and the largest HBCU in Texas.

Texas Southern University, located in the Third Ward, is the first public institution of higher education in Houston and the largest HBCU in Texas. The University of Houston–Downtown, located in Downtown, is the second-largest institution of higher education in Houston.

The University of Houston–Downtown, located in Downtown, is the second-largest institution of higher education in Houston. The University of Houston, located in the Third Ward, is a tier-one public research university and the third-largest institution of higher education in Texas.

The University of Houston, located in the Third Ward, is a tier-one public research university and the third-largest institution of higher education in Texas. Rice University, located near the Museum District and Texas Medical Center, is a private tier-one research university and the most selective institution of higher education in Texas.

Rice University, located near the Museum District and Texas Medical Center, is a private tier-one research university and the most selective institution of higher education in Texas.

Media

The primary network-affiliated television stations are KPRC-TV (NBC), KHOU (CBS), KTRK-TV (ABC), KRIV (Fox), KIAH (The CW), and KTXH (MyNetworkTV). KTRK-TV, KRIV and KTXH operate as owned-and-operated stations of their networks.

The Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land metropolitan area is served by one public television station and one public radio station. KUHT (Houston Public Media) is a PBS member station and is the first public television station in the United States. Houston Public Radio is listener-funded and comprises one NPR member station, KUHF (News 88.7). The University of Houston System owns and holds broadcasting licenses to KUHT and KUHF. The stations broadcast from the Melcher Center for Public Broadcasting, located on the campus of the University of Houston.

Houston is served by the Houston Chronicle, its only major daily newspaper with wide distribution. The Hearst Corporation, which owns and operates the Houston Chronicle, bought the assets of the Houston Post—its long-time rival and main competition—when Houston Post ceased operations in 1995. The Houston Post was owned by the family of former Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby of Houston. The only other major publication to serve the city is the Houston Press—which was a free alternative weekly newspaper before the destruction caused by Hurricane Harvey resulted in the publication switching to an online-only format on November 2, 2017.[220]

Infrastructure

Healthcare

Houston is the seat of the internationally renowned Texas Medical Center, which contains the world's largest concentration of research and healthcare institutions.[221] All 49 member institutions of the Texas Medical Center are non-profit organizations. They provide patient and preventive care, research, education, and local, national, and international community well-being. Employing more than 73,600 people, institutions at the medical center include 13 hospitals and two specialty institutions, two medical schools, four nursing schools, and schools of dentistry, public health, pharmacy, and virtually all health-related careers. It is where one of the first—and still the largest—air emergency service, Life Flight, was created, and a very successful inter-institutional transplant program was developed. More heart surgeries are performed at the Texas Medical Center than anywhere else in the world.[222]

Some of the academic and research health institutions at the center include MD Anderson Cancer Center, Baylor College of Medicine, UT Health Science Center, Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston Methodist Hospital, Texas Children's Hospital, and University of Houston College of Pharmacy.

The Baylor College of Medicine has annually been considered within the top ten medical schools in the nation; likewise, the MD Anderson Cancer Center has consistently ranked as one of the top two U.S. hospitals specializing in cancer care by U.S. News & World Report since 1990.[223][224] The Menninger Clinic, a renowned psychiatric treatment center, is affiliated with Baylor College of Medicine and the Houston Methodist Hospital System.[225] With hospital locations nationwide and headquarters in Houston, the Triumph Healthcare hospital system is the third largest long term acute care provider nationally.[226] Legacy Community Health has opened over 10 locations in Houston, and has been continually expanding in recent years.[227][228]

Transportation

Houston is considered an automobile-dependent city, with an estimated 77.2% of commuters driving alone to work in 2016,[229] up from 71.7% in 1990[230] and 75.6% in 2009.[231] In 2016, another 11.4% of Houstonians carpooled to work, while 3.6% used public transit, 2.1% walked, and 0.5% bicycled.[229] A commuting study estimated that the median length of commute in the region was 12.2 miles (19.6 km) in 2012.[232] According to the 2013 American Community Survey, the average work commute in Houston (city) takes 26.3 minutes.[233] A 1999 Murdoch University study found that Houston had both the lengthiest commute and lowest urban density of 13 large American cities surveyed,[234] and a 2017 Arcadis study ranked Houston 22nd out of 23 American cities in transportation sustainability.[235] Harris County is one of the largest consumers of gasoline in the United States, ranking second (behind Los Angeles County) in 2013.[236]

Despite the region's high rate of automobile usage, attitudes towards transportation among Houstonians indicate a growing preference for walkability. A 2017 study by the Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research found that 56% of Harris County residents have a preference for dense housing in a mixed-use, walkable setting as opposed to single-family housing in a low-density area.[237] A plurality of survey respondents also indicated that traffic congestion was the most significant problem facing the metropolitan area.[237] In addition, many households in the City of Houston have no car. In 2015, 8.3 percent of Houston households lacked a car, which was virtually unchanged in 2016 (8.1 percent). The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Houston averaged 1.59 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[238]

Roadways

The eight-county Greater Houston metropolitan area contains over 25,000 miles (40,000 km) of roadway, of which 10%, or approximately 2,500 miles (4,000 km), is limited-access highway.[239] The Houston region's extensive freeway system handles over 40% of the regional daily vehicle miles traveled (VMT).[239] Arterial roads handle an additional 40% of daily VMT, while toll roads, of which Greater Houston has 180 miles (290 km), handle nearly 10%.[239]

Greater Houston possesses a hub-and-spoke limited-access highway system, in which a number of freeways radiate outward from Downtown, with ring roads providing connections between these radial highways at intermediate distances from the city center. The city is crossed by three Interstate highways, Interstate 10, Interstate 45, and Interstate 69 (commonly known as U.S. Route 59), as well as a number of other United States routes and state highways. Major freeways in Greater Houston are often referred to by either the cardinal direction or geographic location they travel towards. Highways that follow the cardinal convention include U.S. Route 290 (Northwest Freeway), Interstate 45 north of Downtown (North Freeway), Interstate 10 east of Downtown (East Freeway), Texas State Highway 288 (South Freeway), and Interstate 69 south of Downtown (Southwest Freeway). Highways that follow the location convention include Interstate 10 west of Downtown (Katy Freeway), Interstate 69 north of Downtown (Eastex Freeway), Interstate 45 south of Downtown (Gulf Freeway), and Texas State Highway 225 (La Porte or Pasadena Freeway).

Three loop freeways provide north-south and east-west connectivity between Greater Houston's radial highways. The innermost loop is Interstate 610, commonly known as the Inner Loop, which encircles Downtown, the Texas Medical Center, Greenway Plaza, the cities of West University Place and Southside Place, and many core neighborhoods. The 88-mile (142 km) State Highway Beltway 8, often referred to as the Beltway, forms the middle loop at a radius of roughly 10 miles (16 km). A third, 180-mile (290 km) loop with a radius of approximately 25 miles (40 km), State Highway 99 (the Grand Parkway), is currently under construction, with six of eleven segments completed as of 2018.[240] Completed segments D through G provide a continuous 70.4-mile (113.3 km) limited-access tollway connection between Sugar Land, Katy, Cypress, Spring, and Porter.[240]

A system of toll roads, operated by the Harris County Toll Road Authority (HCTRA) and Fort Bend County Toll Road Authority (FBCTRA), provides additional options for regional commuters. The Sam Houston Tollway, which encompasses the mainlanes of Beltway 8 (as opposed to the frontage roads, which are untolled), is the longest tollway in the system, covering the entirety of the Beltway with the exception of a free section between Interstate 45 and Interstate 69 near George Bush Intercontinental Airport. The region is serviced by four spoke tollways: a set of managed lanes on the Katy Freeway; the Hardy Toll Road, which parallels Interstate 45 north of Downtown up to Spring; the Westpark Tollway, which services Houston's western suburbs out to Fulshear; and Fort Bend Parkway, which connects to Sienna Plantation. Westpark Tollway and Fort Bend Parkway are operated conjunctly with the Fort Bend County Toll Road Authority.

Greater Houston's freeway system is monitored by Houston TranStar, a partnership of four government agencies which is responsible for providing transportation and emergency management services to the region.[241]

Greater Houston's arterial road network is established at the municipal level, with the City of Houston exercising planning control over both its incorporated area and extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ). Therefore, Houston exercises transportation planning authority over a 2,000-square-mile (5,200 km2) area over five counties, many times larger than its corporate area.[242] The Major Thoroughfare and Freeway Plan, updated annually, establishes the city's street hierarchy, identifies roadways in need of widening, and proposes new roadways in unserved areas. Arterial roads are organized into four categories, in decreasing order of intensity: major thoroughfares, transit corridor streets, collector streets, and local streets.[242] Roadway classification affects anticipated traffic volumes, roadway design, and right of way breadth. Ultimately, the system is designed to ferry traffic from neighborhood streets to major thoroughfares, which connect into the limited-access highway system.[242] Notable arterial roads in the region include Westheimer Road, Memorial Drive, Texas State Highway 6, Farm to Market Road 1960, Bellaire Boulevard, and Telephone Road.

Transit

The Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (METRO) provides public transportation in the form of buses, light rail, high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes, and paratransit to fifteen municipalities throughout the Greater Houston area and parts of unincorporated Harris County. METRO's service area covers 1,303 square miles (3,370 km2) containing a population of 3.6 million.[243]

METRO's local bus network services approximately 275,000 riders daily with a fleet of over 1,200 buses.[243] The agency's 75 local routes contain nearly 8,900 stops and saw nearly 67 million boardings during the 2016 fiscal year.[243] A park and ride system provides commuter bus service from 34 transit centers scattered throughout the region's suburban areas; these express buses operate independently of the local bus network and utilize the region's extensive system of HOV lanes.[244] Downtown and the Texas Medical Center have the highest rates of transit use in the region, largely due to the park and ride system, with nearly 60% of commuters in each district utilizing public transit to get to work.[244]

METRO began light rail service in 2004 with the opening of the 8-mile (13 km) north-south Red Line connecting Downtown, Midtown, the Museum District, the Texas Medical Center, and NRG Park. In the early 2010s, two additional lines—the Green Line, servicing the East End, and the Purple Line, servicing the Third Ward—opened, and the Red Line was extended northward to Northline, bringing the total length of the system to 22.7 miles (36.5 km). Two light rail lines outlined in a five-line system approved by voters in a 2003 referendum have yet to be constructed.[245] The Uptown Line, which would run along Post Oak Boulevard in Uptown, is currently under construction as a bus rapid transit line—the city's first—while the University Line has been postponed indefinitely.[246] The light rail system saw approximately 16.8 million boardings in fiscal year 2016.[243]

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service three times a week to Houston via the Sunset Limited (Los Angeles–New Orleans), which stops at the Houston Amtrak Station northwest of Downtown. The station saw 14,891 boardings and alightings in fiscal year 2008.[247] In 2012, there was a 25 percent increase in ridership to 20,327 passengers embarking from the Houston Amtrak Station.[248]

Cycling

Houston City Council approved the Houston Bike Plan in March 2017, at that time entering the plan into the Houston Code of Ordinances.[249]

Houston has the largest number of bike commuters in Texas with over 160 miles of dedicated bikeways.[250] The city is currently in the process of expanding its on and off street bikeway network.[251] In 2015, downtown Houston added a cycle track on Lamar Street, running from Sam Houston Park to Discovery Green.[252] In August 2017, Houston City Council approved spending for construction of 13 additional miles of bike trails.[253]

Houston's bicycle sharing system started service with nineteen stations in May 2012. Houston Bcycle (also known as B-Cycle), a local non-profit, runs the subscription program, supplying bicycles and docking stations, while partnering with other companies to maintain the system.[254] The network expanded to 29 stations and 225 bicycles in 2014, registering over 43,000 checkouts of equipment during the first half of the same year.[255] In 2017, Bcycle logged over 142,000 check outs while expanding to 56 docking stations.[256]

Airports

The Houston Airport System, a branch of the municipal government, oversees the operation of three major public airports in the city. Two of these airports, George Bush Intercontinental Airport and William P. Hobby Airport, offer commercial aviation service to a variety of domestic and international destinations and served 55 million passengers in 2016. The third, Ellington Airport, is home to the Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base. The Federal Aviation Administration and the state of Texas selected the Houston Airport System as "Airport of the Year" in 2005, largely due to the implementation of a $3.1 billion airport improvement program for both major airports in Houston.[257]

George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH), located 23 miles (37 km) north of Downtown Houston between Interstates 45 and 69, is the eighth-busiest commercial airport in the United States (by total passengers and aircraft movements) and forty third-busiest globally.[258][259] The five-terminal, five-runway, 11,000-acre (4,500-hectare) airport served 40 million passengers in 2016, including 10 million international travelers.[258] In 2006, the United States Department of Transportation named IAH the fastest-growing of the top ten airports in the United States.[260] The Houston Air Route Traffic Control Center is located at Bush Intercontinental.

Houston was the headquarters of Continental Airlines until its 2010 merger with United Airlines with headquarters in Chicago; regulatory approval for the merger was granted in October of that year. Bush Intercontinental is currently United Airlines' second-largest hub, behind O'Hare International Airport.[261] United Airlines' share of the Houston Airport System's commercial aviation market was nearly 60% in 2017 with 16 million enplaned passengers.[262] In early 2007, Bush Intercontinental Airport was named a model "port of entry" for international travelers by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.[263]

William P. Hobby Airport (HOU), known as Houston International Airport until 1967, operates primarily short- to medium-haul domestic and international flights to 60 destinations.[258] The four-runway, 1,304-acre (528-hectare) facility is located approximately 7 miles (11 km) southeast of Downtown Houston. In 2015, Southwest Airlines launched service from a new international terminal at Hobby to several destinations in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. These were the first international flights flown from Hobby since the opening of Bush Intercontinental in 1969.[264] Houston's aviation history is showcased in the 1940 Air Terminal Museum, located in the old terminal building on the west side of the airport. Hobby Airport has been recognized with two awards for being one of the top five performing airports in the world and for customer service by Airports Council International.[265]

Houston's third municipal airport is Ellington Airport, used by the military, government (including NASA) and general aviation sectors.[266]

Sister cities