History of Kerala

The term Kerala was first epigraphically recorded as Ketalaputo (Cheras) in a 3rd-century BCE rock inscription by emperor Ashoka of Magadha.[1] It was mentioned as one of four independent kingdoms in southern India during Ashoka's time, the others being the Cholas, Pandyas and Satyaputras.[2] The Cheras transformed Kerala into an international trade centre by establishing trade relations across the Arabian Sea with all major Mediterranean and Red Sea ports as well those of the Far East. The early Cheras collapsed after repeated attacks from the neighboring Cholas and Rashtrakutas.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Kerala |

|---|

|

|

Main Megalithic culture Maritime contacts |

|

Other topics |

|

During the early Middle Ages, Namboodiri Brahmin immigrants arrived in Kerala and shaped the society on the lines of the caste system. In the 8th century, Adi Shankara was born at Kalady in central Kerala. He travelled extensively across the Indian subcontinent founding institutions of the widely influential philosophy of Advaita Vedanta. The Cheras regained control over Kerala in the 9th century until the kingdom was dissolved in the 12th century, after which small autonomous chiefdoms, most notably Venadu, arose.

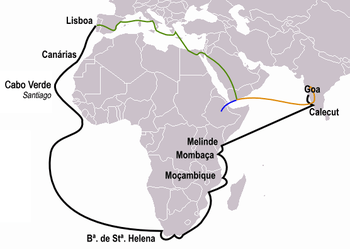

In 1498, Vasco Da Gama established a sea route to Kerala and raised Portuguese settlements, which marked the beginning of the colonial era of Kerala. European trading interests of the Dutch, French and the British East India companies took centre stage during the colonial wars in India. After the Dutch were defeated by Travancore king Marthanda Varma, the British crown gained control over Kerala by allying with the newly created princely state of Travancore until India was declared independent in 1947. The state of Kerala was created in 1956 from the former state of Travancore-Cochin, the Malabar district of Madras State, and the Kasaragod taluk of Dakshina Kannada.[3]

Traditional sources

When?

Mahabali

Perhaps the most famous festival of Kerala, Onam, is deeply rooted in Kerala traditions. Onam is associated with the legendary king Mahabali (Maveli), who according to tradition and Puranas, ruled the Earth and several other planetary systems from Kerala. His entire kingdom was then a land of immense prosperity and happiness. However, Mahabali was tricked into giving up his rule, and was thus overthrown by Vamana (Thrikkakkarayappan), the fifth Avatar (earthly incarnation) of Lord Vishnu. He was banished from the Earth to rule over one of the netherworld (Patala) planets called Sutala by Vamana. Mahabali comes back to visit Kerala every year on the occasion of Onam.[4]

Other texts

The oldest of all the Puranas, the Matsya Purana, sets the story of the Matsya Avatar (fish incarnation) of Lord Vishnu, in the Western Ghats. The earliest Sanskrit text to mention Kerala by name as Cherapadah is the Aitareya Aranyaka, a late Vedic work on philosophy.[5] It is also mentioned in both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.[6]

Parasurama

There are legends dealing with the origins of Kerala geographically and culturally. One such legend is the retrieval of Kerala from the sea, by Parasurama, a warrior sage. It proclaims that Parasurama, an Avatar of Mahavishnu, threw His battle axe into the sea. As a result, the land of Kerala arose, and thus was reclaimed from the waters.[7]

Prehistory

Archaeological studies have identified many Mesolithic, Neolithic and Megalithic sites in Kerala.[8] These findings have been classified into Laterite rock-cut caves (Chenkallara), Hood stones (Kudakkallu), Hat stones (Toppikallu), Dolmenoid cists (Kalvrtham), Urn burials (Nannangadi) and Menhirs (Pulachikallu). The studies point to the indigenous development of the ancient Kerala society and its culture beginning from the Paleolithic age, and its continuity through Mesolithic, Neolithic and Megalithic ages.[9] However, foreign cultural contacts have assisted this cultural formation.[10] The studies suggest possible relationship with Indus Valley Civilization during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age.[11]

Archaeological findings include dolmens of the Neolithic era in the Marayur area. They are locally known as "muniyara", derived from muni (hermit or sage) and ara (dolmen).[12] Rock engravings in the Edakkal Caves in Wayanad are thought to date from the early to late Neolithic eras around 5000 BCE.[13][14][15] Historian M. R. Raghava Varier of the Kerala state archaeology department identified a sign of "a man with jar cup" in the engravings, which is the most distinct motif of the Indus valley civilisation.[16]

Classical period

Early ruling dynasties

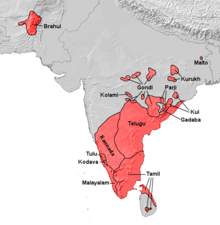

Kerala's dominant rulers of the early historic period were the Cheras, a Tamil dynasty with its headquarters located in Vanchi.[17] The location of Vanchi is generally considered near the ancient port city of Muziris in Kerala.[18][19] However, Karur in modern Tamil Nadu is also pointed out as the location of the capital city of Cheras.[20] Another view suggests the reign of Cheras from multiple capitals.[13] The Chera kingdom consisted of a major part of modern Kerala and Kongunadu which comprises western districts of modern Tamil Nadu like Coimbatore and Salem.[20][21] Old Tamil works such as Patiṟṟuppattu, Patiṉeṇmēlkaṇakku and Silappatikaram are important sources that describe the Cheras from the early centuries CE.[22] Together with the Cholas and Pandyas the Cheras formed the Tamil triumvirate of the mūvēntar (Three Crowned Kings). The Cheras ruled the western Malabar Coast, the Cholas ruled in the eastern Coromandel Coast and the Pandyas in the south-central peninsula. The Cheras were mentioned as Ketalaputo (Keralaputra) on an inscribed edict of emperor Ashoka of the Magadha Empire in the 3rd century BCE,[2] as Cerobothra by the Greek Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and as Celebothras in the Roman encyclopedia Natural History by Pliny the Elder. The Mushika kingdom existed in northern Kerala, while the Ays ruled south of the Chera kingdom.[23]

Trade relations

The region of Kerala was possibly engaged in trading activities from the 3rd millennium BCE with Sumerians and Babylonians.[24] Phoenicians, Greeks, Egyptians, Romans, Jews, Arabs and Chinese were attracted by a variety of commodities, especially spices and cotton fabrics.[25][26]

Muziris, Berkarai, and Nelcynda were among the principal trading port centres of the Chera kingdom.[27] Megasthanes, the Greek ambassador to the court of Magadhan king Chandragupta Maurya (4th century BCE) mentions Muziris and a Pandyan trade centre. Pliny mentions Muziris as India's first port of importance. According to him, Muziris could be reached in 40 days from the Red Sea ports of Egypt purely depending on the South west monsoon winds. Later, the unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea notes that "both Muziris and Nelcynda are now busy places". There were harbours of Naura near Kannur, Tyndis near Koyilandy, and Bacare near Alappuzha which were also trading with Rome and Palakkad pass (churam) facilitated migration and trade. Roman establishments in the port cities of the region, such as a temple of Augustus and barracks for garrisoned Roman soldiers, are marked in the Tabula Peutingeriana; the only surviving map of the Roman cursus publicus.[28][29] The value of Rome's annual trade with the region was estimated at around 50,000,000 sesterces.[30] Contemporary Tamil literature, Puṟanāṉūṟu and Akanaṉūṟu, speak of the Roman vessels and the Roman gold that used to come to the Kerala ports in search of pepper and other spices, which had enormous demand in the West. The contact with Romans might have given rise to small colonies of Jews and Syrian Christians in the chief harbour towns of Kerala.

Formation of a multicultural society

Buddhism and Jainism reached Kerala in this early period. As in other parts of ancient India, Buddhism and Jainism co-existed with early Hindu beliefs during the first five centuries. Merchants from West Asia and Southern Europe established coastal posts and settlements in Kerala.[31] Jews arrived in Kerala as early as 573 BCE.[32][33] The Cochin Jews believe that their ancestors came to the west coast of India as refugees following the destruction of Jerusalem in the first century CE. Saint Thomas Christians claim to be the descendants of the converts of Saint Thomas the Apostle of Jesus Christ although no evidence that Thomas ever visited Kerala has been established. Arabs also had trade links with Kerala, starting before the 4th century BCE, as Herodotus (484–413 BCE) noted that goods brought by Arabs from Kerala were sold to the Jews at Eden.[27] They intermarried with local people, resulting in formation of the Muslim Mappila community. In the 4th century, the Knanaya Christians migrated from Persia and settled in southern Kodungallur.[34][35] Mappila was an honorific title that had been assigned to respected visitors from abroad; and Jewish, Syrian Christian, and Muslim immigration might account for later names of the respective communities: Juda Mappilas, Nasrani Mappilas, and Muslim Mappilas.[36][37] According to the legends of these communities, the earliest Christian churches,[38] mosque,[39] and synagogue (CE 1568)[40] in India were built in Kerala. The combined number of Jews, Christians, and Muslims was relatively small at this early stage. They co-existed harmoniously with each other and with local Hindu society, aided by the commercial benefit from such association.[41]

Early medieval period

Political changes

.jpg)

Much of history of the region from the 6th to the 8th century is obscure.[1] From the Kodungallur line of the Cheras rose the Kulasekhara dynasty, which was established by Kulasekhara Varman. At its zenith these Later Cheras ruled over a territory comprising the whole of modern Kerala and a smaller part of modern Tamil Nadu. During the early part of Kulasekhara period, the southern region from Nagercoil to Thiruvananthapuram was ruled by Ay kings, who lost their power in the 10th century and thus the region became a part of the Cheras.[42][43] Kerala witnessed a flourishing period of art, literature, trade and the Bhakti movement of Hinduism.[44] A Keralite identity, distinct from the Tamils, became linguistically separate during this period.[45] For the local administration, the empire was divided into provinces under the rule of Nair Chieftains known as Naduvazhis, with each province comprising a number of Desams under the control of chieftains, called as Desavazhis.[44] The era witnessed also a shift in political power, evidenced by a gradual increase of Namboothiri Brahmin settlements, who established the caste hierarchy in Kerala by assigning different groups separate positions.[46][47] As a result, many temples were constructed across Kerala, which according to M. T. Narayanan "became cornerstones of the socio-economic society".[47]

The inhibitions, caused by a series of Chera-Chola wars in the 11th century, resulted in the decline of foreign trade in Kerala ports. Buddhism and Jainism disappeared from the land. The Kulasekhara dynasty was finally subjugated in 1102 by the combined attack of the Pandyas and Cholas.[42] However, in the 14th century, Ravi Varma Kulashekhara (1299–1314) of the southern Venad kingdom was able to establish a short-lived supremacy over southern India. After his death, in the absence of a strong central power, the state was fractured into about thirty small warring principalities under Nair Chieftains; most powerful of them were the kingdom of Samuthiri in the north, Venad in the south and Kochi in the middle.[48][49]

Rise of Advaita

Adi Shankara (CE 789), one of the greatest Indian philosophers, is believed to be born in Kaladi in Kerala, and consolidated the doctrine of advaita vedānta.[50][51] Shankara travelled across the Indian subcontinent to propagate his philosophy through discourses and debates with other thinkers. He is reputed to have founded four mathas ("monasteries"), which helped in the historical development, revival and spread of Advaita Vedanta.[51] Adi Shankara is believed to be the organiser of the Dashanami monastic order and the founder of the Shanmatatradition of worship.

His works in Sanskrit concern themselves with establishing the doctrine of advaita (nondualism). He also established the importance of monastic life as sanctioned in the Upanishads and Brahma Sutra, in a time when the Mimamsa school established strict ritualism and ridiculed monasticism. Shankara represented his works as elaborating on ideas found in the Upanishads, and he wrote copious commentaries on the Vedic canon (Brahma Sutra, principal upanishads and Bhagavad Gita) in support of his thesis. The main opponent in his work is the Mimamsa school of thought, though he also offers arguments against the views of some other schools like Samkhya and certain schools of Buddhism.[52][53][54] His activities in Kerala was little and no evidence of his influence is noticed in the literature or other things in his lifetime in Kerala. Even though Sankara was against all caste systems, in later years his name was used extensively by the Brahmins of Kerala for establishing caste system in Kerala.

Kingdom of Venad

Venad was a kingdom in the south west tip of Kerala, which acted as a buffer between Cheras and Pandyas. Until the end of the 11th century, it was a small principality in the Ay Kingdom. The Ays were the earliest ruling dynasty in southern Kerala, who, at their zenith, ruled over a region from Nagercoil in the south to Thiruvananthapuram in the north. Their capital was at Kollam. A series of attacks by the Pandyas between the 7th and 8th centuries caused the decline of Ays although the dynasty remained powerful until the beginning of the 10th century.[55] When Ay power diminished, Venad became the southern most principality of the Second Chera Kingdom[56] Invasion of Cholas into Venad caused the destruction of Kollam in 1096. However, the Chera capital, Mahodayapuram, fell in the subsequent attack, which compelled the Chera king, Rama varma Kulasekara, to shift his capital to Kollam.[57] Thus, Rama Varma Kulasekara, the last emperor of Chera dynasty, is probably the founder of the Venad royal house, and the title of Chera kings, Kulasekara, was thenceforth adopted by the rulers of Venad. The end of Second Chera dynasty in the 12th century marks the independence of the Venad.[58] The Venadu King then also was known as Venadu Mooppil Nayar.

In the second half of the 12th century, two branches of the Ay Dynasty: Thrippappur and Chirava, merged into the Venad family and established the tradition of designating the ruler of Venad as Chirava Moopan and the heir-apparent as Thrippappur Moopan. While Chrirava Moopan had his residence at Kollam, the Thrippappur Moopan resided at his palace in Thrippappur, 9 miles (14 km) north of Thiruvananthapuram, and was vested with the authority over the temples of Venad kingdom, especially the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple.[56] The most powerful kingdom of Kerala during the colonial period, Travancore, was developed through the expansion of Venad by Mahahrajah Marthanda Varma, a member of the Thrippappur branch of the Ay Dynasty who ascended to the throne in the 18th century.

Kingdom of Kozhikode

Historical records regarding the origin of the Samoothiri of Kozhikode is obscure. However, its generally agreed that the Samoothiri were originally the Nairs chieftains of Eralnadu region of the Later Chera Kingdom and were known as the Eradis.[59] Eralnadu province was situated in the northern parts of present-day Malappuram district and was landlocked by the Valluvanad and Polanadu in the west. Legends such as The Origin of Kerala tell the establishment of a local ruling family at Nediyiruppu, near present-day Kondotty by two young brothers belonging to the Eradi clan. The brothers, Manikkan and Vikraman were the most trusted generals in the army of the Cheras.[60][61] M.G.S. Narayanan, a Kerala-based historian, in his book, Calicut: The City of Truth states that the Eradi was a favourite of the last Later Chera king and granted him, as a mark of favor, a small tract of land on the sea-coast in addition to his hereditary possessions (Eralnadu province). Eradis subsequently moved their capital to the coastal marshy lands and established the kingdom of Kozhikode[62] They later assumed the title of Samudrāthiri ("one who has the sea for his border") and continued to rule from Kozhikode.

Samoothiri allied with Muslim Arab and Chinese merchants and used most of the wealth from Kozhikode to develop his military power. They became the most powerful king in the Malayalam speaking regions during the Middle Ages. In the 14th century, Kozhikode conquered large parts of central Kerala, which was under the control of the king of Kingdom of Kochi. He was forced to shift his capital (c. CE 1405) further south. In the 15th century, Kochi was reduced in to a vassal state of Kozhikode .

Colonial period

The maritime spice trade monopoly in the Indian Ocean stayed with the Arabs during the High and Late Middle Ages. However, the dominance of Middle East traders was challenged in the European Age of Discovery. After Vasco Da Gama's arrival in Kappad Kozhikode in 1498, the Portuguese began to dominate eastern shipping, and the spice-trade in particular.[63][64][65]

Portuguese period

The Samoothiri Maharaja of Kozhikode permitted the Portuguese to trade with his subjects. Their trade in Kozhikode prospered with the establishment of a factory and fort in his territory. However, Portuguese attacks on Arab properties in his jurisdiction provoked the Samoothiri and finally led to conflict. The Portuguese took advantage of the rivalry between the Samoothiri and Rajah of Kochi—they allied with Kochi and when Francisco de Almeida was appointed Viceroy of Portuguese India in 1505, he established his headquarters at Kochi. During his reign, the Portuguese managed to dominate relations with Kochi and established a number of fortresses along the Malabar Coast.[66] Nonetheless, the Portuguese suffered severe setbacks due to attacks by Samoothiri Maharaja's forces, especially naval attacks under the leadership of admirals of Kozhikode known as Kunjali Marakkars, which compelled them to seek a treaty. The Portuguese Cemetery, Kollam (after the invasion of Dutch, it became Dutch Cemetery) of Tangasseri in Kollam city was constructed in around 1519 as part of the Portuguese invasion in the city. Buckingham Canal (a small canal between Tangasseri Lighthouse and the cemetery) is situated very close to the Portuguese Cemetery.[67][68] A group of pirates known as the Pirates of Tangasseri formerly lived at the Cemetery.[69] The remnants of St. Thomas Fort and Portuguese Cemetery still exist at Tangasseri.

French Region in Kerala

The French East India Company constructed a fort on the site of Mahé in 1724, in accordance with an accord concluded between André Mollandin and Raja Vazhunnavar of Badagara three years earlier. In 1741, Mahé de La Bourdonnais retook the town after a period of occupation by the Marathas.

In 1761 the British captured Mahé, India, and the settlement was handed over to the Rajah of Kadathanadu. The British restored Mahé, India to the French as a part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris. In 1779, the Anglo-French war broke out, resulting in the French loss of Mahé, India. In 1783, the British agreed to restore to the French their settlements in India, and Mahé, India was handed over to the French in 1785

Dutch period

The weakened Portuguese were ousted by the Dutch East India Company, who took advantage of continuing conflicts between Kozhikode and Kochi to gain control of the trade. The Dutch Malabar (1661–1795) in turn were weakened by their constant battles with Marthanda Varma of the Travancore Royal Family, and were defeated at the Battle of Colachel in 1741, resulting in the complete eclipse of Dutch power in Malabar. The Treaty of Mavelikkara was signed by the Dutch and Travancore in 1753, according to which the Dutch were compelled to detach from all political involvements in the region. In the meantime, Marthanda Varma annexed many smaller northern kingdoms through military conquests, resulting in the rise of Travancore to a position of preeminence in Kerala.[70] Hyder Ali of Mysore conquered northern Kerala in the 18th century, capturing Kozhikode in 1766.

British period

Hyder Ali and his successor, Tipu Sultan, came into conflict with the British, leading to the four Anglo-Mysore wars fought across southern India in the latter half of the 18th century. Tipu Sultan ceded Malabar District to the British in 1792, and South Kanara, which included present-day Kasargod District, in 1799. The British concluded treaties of subsidiary alliance with the rulers of Cochin (1791) and Travancore (1795), and these became princely states of British India, maintaining local autonomy in return for a fixed annual tribute to the British. Malabar and South Kanara districts were part of British India's Madras Presidency.

Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja (Kerul Varma Pyche Rajah, Cotiote Rajah) (3 January 1753 – 30 November 1805) was the Prince Regent and the de facto ruler of the Kingdom of Kottayam in Malabar, India between 1774 and 1805. He led the Pychy Rebellion (Wynaad Insurrection, Coiote War) against the English East India Company. He is popularly known as Kerala Simham (Lion of Kerala).

Organised expressions of discontent with British rule were not uncommon in Kerala. Uprisings of note include the rebellion by Pazhassi Raja, Velu Thampi Dalawa and the Punnapra-Vayalar revolt of 1946. In 1919, consequent to their victory in World War I, the British abolished the Islamic Caliphate and dismembered the Ottoman Empire. This resulted in protests against the British by Muslims of the Indian sub-continent known as the Khilafat Movement, which was supported by Mahatma Gandhi in order to draw the Muslims into the mainstream national independence movement. In 1921, the Khilafat Movement in Malabar culminated in widespread riots against the British government and Hindu population in what is now known as the Moplah rebellion. Kerala also witnessed several social reforms movements directed at the eradication of social evils such as untouchability among the Hindus, pioneered by reformists like Srinarayana guru and Chattambiswami among others. The non-violent and largely peaceful Vaikom Satyagraha of 1924 was instrumental in securing entry to the public roads adjacent to the Vaikom temple for people belonging to untouchable castes. In 1936, Sree Chithira Thirunal Balaramavarma, the ruler of Travancore, issued the Temple Entry Proclamation, declaring the temples of his kingdom open to all Hindu worshipers, irrespective of caste.

Modern history

Formation of Kerala state

The two kingdoms of Travancore and Cochin joined the Union of India after independence in 1947. On 1 July 1949, the two states were merged to form Travancore-Cochin. On 1 January 1950, Travancore-Cochin was recognised as a state. The Madras Presidency was reorganised to form Madras State in 1947.

On 1 November 1956, the state of Kerala was formed by the States Reorganisation Act merging the Malabar district, Travancore-Cochin (excluding four southern taluks, which were merged with Tamil Nadu), and the taluk of Kasargod, South Kanara.[71] In 1957, elections for the new Kerala Legislative Assembly were held, and a reformist, Communist-led government came to power, under E. M. S. Namboodiripad.[71] It was the first time a Communist government was democratically elected to power anywhere in the world. It initiated pioneering land reforms, aiming to lowering of rural poverty in Kerala. However, these reforms were largely non-effective to mark a greater change in the society as these changes were not effected to a large extend. Lakhs of farms were owned by large establishments, companies and estate owners. They were not affected by this move and this was considered as a treachery as these companies and estates were formed by and during the British rule. Two things were the real reason for the reduction of poverty in Kerala one was the policy for wide scale education and second was the overseas migration for labour to Middle east and other countries.[72][73]

Liberation struggle

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

|

Origins Dravidian People |

|

History

|

|

Culture

|

|

Language

|

|

Regions

|

|

People

|

|

Politics |

| Portal:Dravidian civilizations |

It refused to nationalise the large estates but did provide reforms to protect manual labourers and farm workers, and invited capitalists to set up industry. Much more controversial was an effort to impose state control on private schools, such as those run by the Christians and the NSS, which enrolled 40% of the students. The Christians, NSS and Namputhiris and the Congress Party protested, with demonstrations numbering in the tens and hundreds of thousands of people. The government controlled the police, which made 150,000 arrests (often the same people arrested time and again), and used 248 lathi charges to beat back the demonstrators, killing twenty. The opposition called on Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to seize control of the state government. Nehru was reluctant but when his daughter Indira Gandhi, the national head of the Congress Party, joined in, he finally did so. New elections in 1959 cost the Communists most of their seats and Congress resumed control.

Coalition politics

Later in 1967-82 Kerala elected a series of leftist coalition governments; the most stable was that led by Achutha Menon from 1969 to 1977.[74]

From 1967 to 1970, Kunnikkal Narayanan led a Naxalite movement in Kerala. The theoretical difference in the communist party, i.e. CPM is the part of the uprising of Naxalbari movement in Bengal which leads to the formation of CPI(ML) in India. Due to ideological differences the CPI-ML split into several groups. Some groups choose to participate peacefully in electoralism, while some choose to aim for violent revolution. The violence alienated public opinion.[75]

The political alliance have strongly stabilised in such a manner that, with rare exceptions, most of the coalition partners stick their loyalty to the alliance. As a result, to this, ever since 1979, the power has been clearly alternating between these two fronts without any change. Politics in Kerala is characterised by continually shifting alliances, party mergers and splits, factionalism within the coalitions and within political parties, and numerous splinter groups.[76]

Modern politics in Kerala is dominated by two political fronts: the Communist-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) and the Indian National Congress-led United Democratic Front (UDF) since the late 1970s. These two parties have alternating in power since 1982. Most of the major political parties in Kerala, except for Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), belong to one or the other of these two alliances, often shifting allegiances a number of time.[76] As of the 2016 Kerala Legislative Assembly election, the LDF has a majority in the state assembly seats (91/140).

References

- "Kerala." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2011. Web. 26 December 2011.

- Vincent A. Smith; A. V. Williams Jackson (30 November 2008). History of India, in Nine Volumes: Vol. II – From the Sixth Century BCE to the Mohammedan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great. Cosimo, Inc. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-1-60520-492-5. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "The land that arose from the sea". The Hindu. 1 November 2003. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- Sreedhara Menon, A. (2008). Legacy of Kerala. DC Books.

- Sreedhara Menon, A. (2008). Kerala History and its Makers. DC Books.

- A. Sreedhara Menon (2008). Cultural Heritage of Kerala. D C Books. pp. 13–15. ISBN 9788126419036.

- Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–212. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 116. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. pp. 118, 123. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- "Symbols akin to Indus valley culture discovered in Kerala". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 29 September 2009.

- "Unlocking the secrets of history". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 December 2004.

- Subodh Kapoor (1 July 2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 2184. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- http://www.hindu.com/2007/10/30/stories/2007103054660500.htmHindu.com. Retrieved 10 October 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Tourism information on districts–Wayanad Archived 14 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, official website of the Govt. of Kerala

- "Symbols akin to Indus valley culture discovered in Kerala". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 29 September 2009.

- Angelina Vimala (1 September 2007). History And Civics 6. Pearson Education India. p. 107. ISBN 978-81-317-0336-6. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- A. Sreedhara Menon (1987). Political History of Modern Kerala. D C Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-81-264-2156-5. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- Miguel Serrano (1 January 1974). The Serpent of Paradise: The Story of an Indian Pilgrimage. Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-7100-7784-4. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- K. Krishna Reddy. Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-07-132923-1. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- Subodh Kapoor (1 July 2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 1448. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- John Ralston Marr (1985). The Eight Anthologies. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 263.

- Sreedhara Menon, A. (2008). Kerala History and its Makers. DC Books. p. 22.

- Striving for sustainability, environmental stress and democratic initiatives in Kerala, p. 79; ISBN 81-8069-294-9, Srikumar Chattopadhyay, Richard W. Franke; Year: 2006.

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Faces of Goa: a journey through the history and cultural revolution of Goa and other communities influenced by the Portuguese By Karin Larsen (Page 392)

- K. K. Kusuman (1987). A History of Trade & Commerce in Travancore. Mittal Publications. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-81-7099-026-0. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Abraham Eraly (1 December 2011). The First Spring: The Golden Age of India. Penguin Books India. pp. 246–. ISBN 978-0-670-08478-4. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Iyengar PTS (2001). History of the Tamils: From the Earliest Times to 600 A.D. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0145-9. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- According to Pliny the Elder, goods from India were sold in the Empire at 100 times their original purchase price. See

- Iyengar PTS (2001). History of the Tamils: From the Earliest Times to 600 CE. Asian Educational Services. pp. 192–195. ISBN 81-206-0145-9. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- De Beth Hillel, David (1832). Travels (Madraspublication).

- Lord, James Henry (1977). The Jews in India and the Far East; Greenwood Press Reprint; ISBN.

- The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 5 by Erwin Fahlbusch. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing - 2008, Page 285. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2.

- Geoffrey Wainwright (2006). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press. p. 666. ISBN 9780195138863.

-

- Bindu Malieckal (2005) Muslims, Matriliny, and A Midsummer Night's Dream: European Encounters with the Mappilas of Malabar, India; The Muslim World Volume 95 Issue 2

- Milton J, Skeat WW, Pollard AW, Brown L (31 August 1982). The Indian Christians of St Thomas. Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-521-21258-8.

- Susan Bayly (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780521891035.

- Jonathan Goldstein (1999). The Jews of China. M.E. Sharpe. p. 123. ISBN 9780765601049.

- Nathan Katz (2000). Who Are the Jews of India?. University of California Press. p. 245. ISBN 9780520213234.

- Rolland E. Miller (1993). Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Perspectives and Encounters. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 50. ISBN 9788120811584.

- K. Balachandran Nayar (1974). In quest of Kerala. Accent Publications. p. 86. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 97. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 123–131. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- Chaitanya, Krishna (1972). Kerala. New Delhi: National Book Trust, India; [chief stockists in India: India Book House, Bombay]. p. 15. OCLC 515788.

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 138. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- M. T. Narayanan (2003). Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar. Northern Book Centre.

- Educational Britannica Educational (15 August 2010). The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- "The Territories and States of India". Europa – via Questia (subscription required) . 2002. pp. 144–146. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- Sharma, Chandradhar (1962). "Chronological Summary of History of Indian Philosophy". Indian Philosophy: A Critical Survey. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. vi.

- The Seven Spiritual Laws Of Yoga, Deepak Chopra, John Wiley & Sons, 2006, ISBN 81-265-0696-2, ISBN 978-81-265-0696-5

- Sri Adi Shankaracharya, Sringeri Sharada Peetham, India

- Biography of Sri Adi Shankaracharya, Sringeri Sharada Peetham, India

- The philosophy of Sankar's Advaita Vedanta, Shyama Kumar Chattopadhyaya, Sarup & Sons, 2000, ISBN 81-7625-222-0, ISBN 978-81-7625-222-5

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 139. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 141. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Krishna Iyer, K. V. (1938). The Zamorins of Calicut.

- "officialwebsite of". Kerala.gov.in. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- Divakaran, Kattakada (2005). Kerala Sanchaaram. Trivandrum: Z Library.

- To corroborate his assertion that Eradi was in fact a favourite of the last Later Chera, M.G.S. cites a stone inscription discovered at Kollam in southern Kerala. It refers to "Nalu Taliyum, Ayiram, Arunurruvarum, Eranadu Vazhkai Manavikiraman, mutalayulla Samathararum" - "The four Councillors, The Thousand, The Six Hundred, along with Mana Vikrama-the Governor of Eralnadu and other Feudatories." M.G.S. indicates that Kozhikode lay in fact beyond and not within the kingdom of Polanadu and there was no need of any kind of military movements for Kozhikode.

- Charles Corn (1999) [First published 1998]. The Scents of Eden: A History of the Spice Trade. Kodansha America. pp. 4–5. ISBN 1-56836-249-8.

- PN Ravindran (2000). Black Pepper: Piper Nigrum. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-5702-453-5. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- PD Curtin (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0-521-26931-8.

- J. L. Mehta (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: Volume One: 1707 - 1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 324–327. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Tangasseri - OOCITIES". OOCITIES. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "Archaeological site and remains". Archaeological Survey of India - Thrissur Circle. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "A brief history of Tangasseri". Rotary Club of Tangasseri. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- A. Sreedhara Menon (1987). Political History of Modern Kerala. D C Books. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-264-2156-5. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Plunkett, Cannon & Harding 2001, p. 24

- Biswas, Soutik (17 March 2010). "Conundrum of Kerala's struggling economy by Soutik Biswas". BBC News. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- Thomas Johnson Nossiter (1982). Communism in Kerala: a study in political adaptation. C. Hurst for the Royal Institute of International Affairs. ISBN 0-905838-40-8.

- Ramachandra Guha (2011). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Pan Macmillan. pp. 290–301. ISBN 9780330540209.

- K. Sreejith, "Naxalites and the New Democratic Revolution: The Kerala Experience 1967-70," Bengal Past & Present: A Journal of Modern Indian & Asian History (1999) 118#2 pp 69-82

- "Refworld | India: 1. Please provide some background as to the politics of the State of Kerala, particularly clashes between the CPIM and INC or DIC or their student arms. 2. Is there any information of Simon Britto and whether he is a legislative assembly member? 3. Which party was in power in Kerala State Assembly from the early 1980s? 4. Please provide some background on the Democratic Indira Congress and Mr. Karunakaran in Kerala. 5. Please provide background or any detail on RSS attacks on Christians particularly in Chitoor, Kerala". Australia: Refugee Review Tribunal. 19 March 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

Further reading

- Bose, Satheese Chandra and Varughese, Shiju Sam (eds.) 2015. Kerala Modernity: Ideas, Spaces and Practices in Transition. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan.

- Franke, Richard W., Pyralal Raghavan and T. M. Thomas Isaac. Democracy at Work in an Indian Industrial Cooperative: The Story of Kerala Dinesh Beedi (1998) excerpt and text search

- Kumar, S. Political evolution in Kerala: Travancore 1859-1938 (New Delhi: Phoenix Publishing House, 1994)

- Jose, D (1998), "EMS Namboodiripad dead", Rediff, retrieved 12 January 2006

- Menon, K.P. Padmanabha. History of Kerala (4 vol 1929)

- Menon, A. Sreedhara (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786.

- Osella, F. & C. Osella Social mobility in Kerala: modernity and identity in conflict (London: Pluto, 2000)

- Palackal, Antony and Wesley Shrum. Information Society and Development: The Kerala Experience (2007)

- Plunkett, R; Cannon, T, Davis, P, Greenway, P; Harding, P (2001), Lonely Planet South India, Lonely Planet, ISBN 1-86450-161-8

- Singh, Anjana (2010). Fort Cochin in Kerala, 1750-1830: The Social Condition of a Dutch Community in an Indian Milieu. Brill. ISBN 978-9004168169.

- Singh, Raghubir. Kerala: The Spice Coast of India by Raghubir Singh (1986)

- Government of Travancore (1906), The Travancore State Manual, Travancore Government Press, retrieved 12 January 2006