Coconut

The coconut tree (Cocos nucifera) is a member of the palm tree family (Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus Cocos.[1] The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut")[2] can refer to the whole coconut palm, the seed, or the fruit, which botanically is a drupe, not a nut. The name comes from the old Portuguese and Spanish word coco, meaning 'head' or 'skull' after the three indentations on the coconut shell that resemble facial features. They are ubiquitous in coastal tropical regions, and are a cultural icon of the tropics.

| Coconut | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coconut palm (Cocos nucifera) | |

| |

| Coconut fruits | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Subfamily: | Arecoideae |

| Tribe: | Cocoseae |

| Genus: | Cocos L. |

| Species: | C. nucifera |

| Binomial name | |

| Cocos nucifera L. | |

| |

| Native range of Cocos nucifera prior to its cultivation. | |

It is one of the most useful trees in the world, and is often referred to as the "tree of life". It provides food, fuel, cosmetics, folk medicine and building materials, among many other uses. The inner flesh of the mature seed, as well as the coconut milk extracted from it, forms a regular part of the diets of many people in the tropics and subtropics. Coconuts are distinct from other fruits because their endosperm contains a large quantity of clear liquid, called coconut water or coconut juice. Mature, ripe coconuts can be used as edible seeds, or processed for oil and plant milk from the flesh, charcoal from the hard shell, and coir from the fibrous husk. Dried coconut flesh is called copra, and the oil and milk derived from it are commonly used in cooking – frying in particular – as well as in soaps and cosmetics. The hard shells, fibrous husks and long pinnate leaves can be used as material to make a variety of products for furnishing and decoration.

The coconut has cultural and religious significance in certain societies, particularly in India, where it is used in Hindu rituals. It forms the basis of wedding and worship rituals in Hinduism, a coconut religion in Vietnam, and features in the origin myths of several societies. The falling nature of their mature fruit has led to preoccupation with death by coconut.[3]

Coconuts have been used by humans for thousands of years, and may have spread to their present range because of Pacific island settlers. The evolutionary origin of the coconut is under dispute, with theories stating that it may have evolved in Asia, South America, or on islands in the Pacific. Trees grow up to 30 m (98 ft) tall and can yield up to 75 fruits per year, though less than 30 is more typical. Plants are intolerant of cold weather and prefer copious precipitation, as well as full sunlight. Many insect pests and diseases affect the species, and are a nuisance for commercial production. About 74% of the world's supply of coconuts derives from Indonesia, the Philippines, and India combined.

Etymology

The name coconut is derived from the 16th-century Portuguese and Spanish word coco, meaning 'head' or 'skull' after the three indentations on the coconut shell that resemble facial features.[4][5][6] Coco and coconut apparently came from 1521 encounters by Portuguese and Spanish explorers with Pacific islanders, with the coconut shell reminding them of a ghost or witch in Portuguese folklore called coco (also côca).[7][8] In the West it was originally called nux indica, a name used by Marco Polo in 1280 while in Sumatra. He took the term from the Arabs, who called it جوز هندي jawz hindī, translating to 'Indian nut'.[9] Thenga, its Malayalam name, was used in the detailed description of coconut found in Itinerario by Ludovico di Varthema published in 1510 and also in the later Hortus Indicus Malabaricus.[10]

The specific name nucifera is Latin for 'nut-bearing'.

History

Literary evidence from the Ramayana and Sri Lankan chronicles indicates that the coconut was present in the Indian subcontinent before the 1st century BCE.[12] The earliest direct description is given by Cosmas Indicopleustes in his Topographia Christiana written around 545, referred to as "the great nut of India".[13] Another early mention of the coconut dates back to the "One Thousand and One Nights" story of Sinbad the Sailor wherein he bought and sold a coconut during his fifth voyage.[14]

In March 1521, a description of the coconut was given by Antonio Pigafetta writing in Italian and using the words "cocho"/"cochi", as recorded in his journal after the first European crossing of the Pacific Ocean during the Magellan circumnavigation and meeting the inhabitants of what would become known as Guam and the Philippines. He explained how at Guam "they eat coconuts" ("mangiano cochi") and that the natives there also "anoint the body and the hair with coconut and beniseed oil" ("ongieno el corpo et li capili co oleo de cocho et de giongioli").[15]

Origin

.png)

The American botanist Orator F. Cook proposed a theory in 1901 on the location of the origin of Cocos nucifera based on its current worldwide distribution. He hypothesized that the coconut originated in the Americas, based on his belief that American coconut populations predated European contact and because he considered pan-tropical distribution by ocean currents improbable.[18][19]

.png)

Modern genetic studies have identified the center of origin of coconuts as being the region between Southwest Asia and Melanesia, where it shows greatest genetic diversity.[23][24][25][20] Their cultivation and spread was closely tied to the early migrations of the Austronesian peoples who carried coconuts as canoe plants to islands they settled.[25][20][26][22] The similarities of the local names in the Austronesian region is also cited as evidence that the plant originated in the region. For example, the Polynesian and Melanesian term niu; Tagalog and Chamorro term niyog; and the Malay word nyiur or nyior.[27][28]

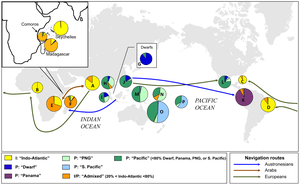

A study in 2011 identified two highly genetically differentiated subpopulations of coconuts, one originating from Island Southeast Asia (the Pacific group) and the other from the southern margins of the Indian subcontinent (the Indo-Atlantic group). The Pacific group is the only one to display clear genetic and phenotypic indications that they were domesticated; including dwarf habit, self-pollination, and the round "niu vai" fruit morphology with larger endosperm-to-husk ratios. The distribution of the Pacific coconuts correspond to the regions settled by Austronesian voyagers indicating that its spread was largely the result of human introductions. It is most strikingly displayed in Madagascar, an island settled by Austronesian sailors at around 2000 to 1500 BP. The coconut populations in the island show genetic admixture between the two subpopulations indicating that Pacific coconuts were brought by the Austronesian settlers that later interbred with the local Indo-Atlantic coconuts.[20][26]

Genetic studies of coconuts have also confirmed pre-Columbian populations of coconuts in Panama in South America. However, it is not native and display a genetic bottleneck resulting from a founder effect. A study in 2008 showed that the coconuts in the Americas are genetically closest related to coconuts in the Philippines, and not to any other nearby coconut populations (including Polynesia). Such an origin indicates that the coconuts were not introduced naturally, such as by sea currents. The researchers concluded that it was brought by early Austronesian sailors to the Americas from at least 2,250 BP, and may be proof of pre-Columbian contact between Austronesian cultures and South American cultures, albeit in the opposite direction than what early hypotheses like Heyerdahl's had proposed. It is further strengthened by other similar botanical evidence of contact, like the pre-colonial presence of sweet potato in Oceanian cultures.[25][22][32] During the colonial era, Pacific coconuts were further introduced to Mexico from the Spanish East Indies via the Manila galleons.[20]

In contrast to the Pacific coconuts, Indo-Atlantic coconuts were largely spread by Arab and Persian traders into the East African coast. Indo-Atlantic coconuts were also introduced into the Atlantic Ocean by Portuguese ships from their colonies in coastal India and Sri Lanka; first being introduced to coastal West Africa, then onwards into the Caribbean and the east coast of Brazil. All of these introductions are within the last few centuries, relatively recent in comparison to the spread of Pacific coconuts.[20]

In attempting to determine whether the species had originated in South America or Asia, a 2014 study proposed that it was neither, and that the species evolved on coral atolls in the Pacific. Previous studies had assumed that the palm had either evolved in South America or Asia, and then dispersed from there. The 2014 study hypothesized that instead the species evolved while on coral atolls in the Pacific, and then dispersed to the continents. It contended that this would have provided the necessary evolutionary pressures, and would account for morphological factors such as a thick husk to protect against ocean degradation and provide a moist medium in which to germinate on sparse atolls.[33]

Evolutionary history

The evolutionary history and fossil distribution of Cocos nucifera and other members of the tribe Cocoseae is more ambiguous than modern-day dispersal and distribution, with its ultimate origin and pre-human dispersal still unclear. There are currently two major viewpoints on the origins of the genus Cocos, one in the Indo-Pacific, and another in South America.[34][35] The vast majority of Cocos-like fossils have been recovered generally from only two regions in the world: New Zealand and west-central India. However, like most palm fossils, Cocos-like fossils are still putative, as they are usually difficult to identify.[35] The earliest Cocos-like fossil to be found was "Cocos" zeylanica, a fossil species described from small fruits, around 3.5 cm (1.4 in) × 1.3 to 2.5 cm (0.51 to 0.98 in) in size, recovered from the Miocene (~23 to 5.3 million years ago) of New Zealand in 1926. Since then, numerous other fossils of similar fruits were recovered throughout New Zealand from the Eocene, Oligocene, and possibly the Holocene. But research on them is still ongoing to determine which of them (if any) actually belong to the genus Cocos.[35][36] Endt & Hayward (1997) have noted their resemblance to members of the South American genus Parajubaea, rather than Cocos, and propose a South American origin.[35][37][38] Conran et al. (2015), however, suggests that their diversity in New Zealand indicate that they evolved endemically, rather than being introduced to the islands by long-distance dispersal.[36] In west-central India, numerous fossils of Cocos-like fruits, leaves, and stems have been recovered from the Deccan Traps. They include morphotaxa like Palmoxylon sundaran, Palmoxylon insignae, and Palmocarpon cocoides. Cocos-like fossils of fruits include "Cocos" intertrappeansis, "Cocos" pantii, and "Cocos" sahnii. They also include fossil fruits that have been tentatively identified as modern Cocos nucifera. These includes two specimens named "Cocos" palaeonucifera and "Cocos" binoriensis, both were dated by their authors to the Maastrichtian–Danian of the early Tertiary (70 to 62 million years ago). C. binoriensis has been claimed by their authors to be the earliest known fossil of Cocos nucifera.[34][35][39]

Outside of New Zealand and India, only two other regions have reported Cocos-like fossils, namely Australia and Colombia. In Australia, a Cocos-like fossil fruit, measuring 10 cm (3.9 in) × 9.5 cm (3.7 in), were recovered from the Chinchilla Sand Formation dated to the latest Pliocene or basal Pleistocene. Rigby (1995) assigned them to modern Cocos nucifera based on its size.[34][35] In Colombia, a single Cocos-like fruit was recovered from the middle to late Paleocene Cerrejón Formation. The fruit however was compacted in the fossilization process and it was not possible to determine if it had the diagnostic three pores that characterize members of the tribe Cocoseae. Nevertheless, the authors Gomez-Navarro et al. (2009), assigned it to Cocos based on the size and the ridged shape of the fruit.

Description

Plant

Cocos nucifera is a large palm, growing up to 30 m (100 ft) tall, with pinnate leaves 4–6 m (13–20 ft) long, and pinnae 60–90 cm (2–3 ft) long; old leaves break away cleanly, leaving the trunk smooth.[41] On fertile soil, a tall coconut palm tree can yield up to 75 fruits per year, but more often yields less than 30.[42][43][44] Given proper care and growing conditions, coconut palms produce their first fruit in six to ten years, taking 15 to 20 years to reach peak production.[45]

Many different varieties are grown, including the Maypan coconut, King coconut, and Macapuno. These vary by the taste of the coconut water and color of the fruit, as well as other genetic factors. Dwarf varieties are also available.[46]

Fruit

Botanically, the coconut fruit is a drupe, not a true nut.[47] Like other fruits, it has three layers: the exocarp, mesocarp, and endocarp. The exocarp and mesocarp make up the "husk" of the coconuts. The endosperm is initially in its nuclear phase suspended within the coconut water. As development continues, cellular layers of endosperm deposit along the walls of the coconut, becoming the edible coconut "flesh".[48] Coconuts sold in the shops of nontropical countries often have had the exocarp (outermost layer) removed. The mesocarp is composed of a fiber, called coir, which has many traditional and commercial uses. The shell has three germination pores (micropyles) or "eyes" that are clearly visible on its outside surface once the husk is removed.

A full-sized coconut weighs about 1.4 kg (3.1 lb). It takes around 6,000 full-grown coconuts to produce one tonne of copra.[49]

Roots

Unlike some other plants, the palm tree has neither a tap root nor root hairs, but has a fibrous root system.[50] The root system consists of an abundance of thin roots that grow outward from the plant near the surface. Only a few of the roots penetrate deep into the soil for stability. This type of root system is known as fibrous or adventitious, and is a characteristic of grass species. Other types of large trees produce a single downward-growing tap root with a number of feeder roots growing from it. 2,000-4,000 adventitious roots may grow, each about 1 cm (0.39 in) large. Decayed roots are replaced regularly as the tree grows new ones.[24]

Inflorescence

The palm produces both the female and male flowers on the same inflorescence; thus, the palm is monoecious.[50] However, there is some evidence that it may be polygamomonoecious, and may occasionally have bisexual flowers.[51] The female flower is much larger than the male flower. Flowering occurs continuously. Coconut palms are believed to be largely cross-pollinated, although some dwarf varieties are self-pollinating.

Distribution

Coconuts have a nearly cosmopolitan distribution thanks to human action in using them for agriculture. However their historical distribution was likely more limited.

Natural habitat

The coconut palm thrives on sandy soils and is highly tolerant of salinity. It prefers areas with abundant sunlight and regular rainfall (1,500–2,500 mm [59–98 in] annually), which makes colonizing shorelines of the tropics relatively straightforward.[52] Coconuts also need high humidity (at least 70–80%) for optimum growth, which is why they are rarely seen in areas with low humidity. However, they can be found in humid areas with low annual precipitation such as in Karachi, Pakistan, which receives only about 250 mm (9.8 in) of rainfall per year, but is consistently warm and humid.

Coconut palms require warm conditions for successful growth, and are intolerant of cold weather. Some seasonal variation is tolerated, with good growth where mean summer temperatures are between 28 and 37 °C (82 and 99 °F), and survival as long as winter temperatures are above 4–12 °C (39–54 °F); they will survive brief drops to 0 °C (32 °F). Severe frost is usually fatal, although they have been known to recover from temperatures of −4 °C (25 °F).[52] They may grow but not fruit properly in areas with insufficient warmth, such as Bermuda.

The conditions required for coconut trees to grow without any care are:

- Mean daily temperature above 12–13 °C (54–55 °F) every day of the year

- Mean annual rainfall above 1,000 mm (39 in)

- No or very little overhead canopy, since even small trees require direct sun

The main limiting factor for most locations which satisfy the rainfall and temperature requirements is canopy growth, except those locations near coastlines, where the sandy soil and salt spray limit the growth of most other trees.

Domestication

Coconuts could not reach inland locations without human intervention (to carry seednuts, plant seedlings, etc.) and early germination on the palm (vivipary) was important,[53] rather than increasing the number or size of the edible parts of a fruit that was already large enough. Human cultivation of the coconut selected, not for larger size, but for thinner husks and increased volume of endosperm, the solid "meat" or liquid "water" that provides the fruit its food value. Although these modifications for domestication would reduce the fruit's ability to float, this ability would be irrelevant to a cultivated population.

Among modern C. nucifera, two major types or variants occur: a thick-husked, angular fruit and a thin-husked, spherical fruit with a higher proportion of endosperm reflect a trend of cultivation in C. nucifera. The first coconuts were of the niu kafa type, with thick husks to protect the seed, an angular, highly ridged shape to promote buoyancy during ocean dispersal, and a pointed base that allowed fruits to dig into the sand, preventing them from being washed away during germination on a new island. As early human communities began to harvest coconuts for eating and planting, they (perhaps unintentionally) selected for a larger endosperm-to-husk ratio and a broader, spherical base, which rendered the fruit useful as a cup or bowl, thus creating the niu vai type. The decreased buoyancy and increased fragility of this spherical, thin-husked fruit would not matter for a species that had started to be dispersed by humans and grown in plantations. Harries' adoption of the Polynesian terms niu kafa and niu vai has now passed into general scientific discourse, and his hypothesis is generally accepted.[54][55]

Variants of C. nucifera are also categorized as tall (var. typica) or dwarf (var. nana).[56] The two groups are genetically distinct, with the dwarf variety showing a greater degree of artificial selection for ornamental traits and for early germination and fruiting.[57][58] The tall variety is outcrossing while dwarf palms are incrossing, which has led to a much greater degree of genetic diversity within the tall group. The dwarf subspecies is thought to have mutated from the tall group under human selection pressure.[59]

Dispersal

Coconut fruit in the wild are light, buoyant, and highly water resistant. It is claimed that they evolved to disperse significant distances via marine currents.[60] However, it can also be argued that the placement of the vulnerable eye of the nut (down when floating), and the site of the coir cushion are better positioned to ensure that the water-filled nut does not fracture when dropping on rocky ground, rather than for flotation.

It is also often stated that coconuts can travel 110 days, or 3,000 miles (4,800 km), by sea and still be able to germinate.[61] This figure has been questioned based on the extremely small sample size that forms the basis of the paper that makes this claim.[32] Thor Heyerdahl provides an alternative, and much shorter, estimate based on his first-hand experience crossing the Pacific Ocean on the raft Kon-Tiki:

"The nuts we had in baskets on deck remained edible and capable of germinating the whole way to Polynesia. But we had laid about half among the special provisions below deck, with the waves washing around them. Every single one of these was ruined by the sea water. And no coconut can float over the sea faster than a balsa raft moves with the wind behind it."[62]

He also notes that several of the nuts began to germinate by the time they had been ten weeks at sea, precluding an unassisted journey of 100 days or more.[32]

Drift models based on wind and ocean currents have shown that coconuts could not have drifted across the Pacific unaided.[32] If they were naturally distributed and had been in the Pacific for a thousand years or so, then we would expect the eastern shore of Australia, with its own islands sheltered by the Great Barrier Reef, to have been thick with coconut palms: the currents were directly into, and down along this coast. However, both James Cook and William Bligh[63] (put adrift after the Bounty mutiny) found no sign of the nuts along this 2,000 km (1,200 mi) stretch when he needed water for his crew. Nor were there coconuts on the east side of the African coast until Vasco da Gama, nor in the Caribbean when first visited by Christopher Columbus. They were commonly carried by Spanish ships as a source of sweet water.

These provide substantial circumstantial evidence that deliberate Austronesian voyagers were involved in carrying coconuts across the Pacific Ocean and that they could not have dispersed worldwide without human agency. More recently, genomic analysis of cultivated coconut (C. nucifera L.) has shed light on the movement. However, admixture, the transfer of genetic material, evidently occurred between the two populations.[64]

Given that coconuts are ideally suited for inter-island group ocean dispersal, obviously some natural distribution did take place. However, the locations of the admixture events are limited to Madagascar and coastal east Africa, and exclude the Seychelles. This pattern coincides with the known trade routes of Austronesian sailors. Additionally, a genetically distinct subpopulation of coconut on the Pacific coast of Latin America has undergone a genetic bottleneck resulting from a founder effect; however, its ancestral population is the Pacific coconut from the Philippines. This, together with their use of the South American sweet potato, suggests that Austronesian peoples may have sailed as far east as the Americas.[64]

Specimens have been collected from the sea as far north as Norway (but it is not known where they entered the water).[65] In the Hawaiian Islands, the coconut is regarded as a Polynesian introduction, first brought to the islands by early Polynesian voyagers from their homelands in the southern islands of Polynesia.[9] They have been found in the Caribbean and the Atlantic coasts of Africa and South America for less than 500 years (the Caribbean native inhabitants do not have a dialect term for them, but use the Portuguese name), but evidence of their presence on the Pacific coast of South America antedates Christopher Columbus's arrival in the Americas.[23] They are now almost ubiquitous between 26° N and 26° S except for the interiors of Africa and South America.

The 2014 coral atoll origin hypothesis proposed that the coconut had dispersed in an island hopping fashion using the small, sometimes transient, coral atolls. It noted that by using these small atolls, the species could easily island-hop. Over the course of evolutionary time-scales the shifting atolls would have shortened the paths of colonization, meaning that any one coconut would not have to travel very far to find new land.[33]

Ecology

Pests and diseases

Coconuts are susceptible to the phytoplasma disease, lethal yellowing. One recently selected cultivar, the 'Maypan', has been bred for resistance to this disease.[66] Yellowing diseases affect plantations in Africa, India, Mexico, the Caribbean and the Pacific Region.[67]

The coconut palm is damaged by the larvae of many Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) species which feed on it, including the African armyworm (Spodoptera exempta) and Batrachedra spp.: B. arenosella, B. atriloqua (feeds exclusively on C. nucifera), B. mathesoni (feeds exclusively on C. nucifera), and B. nuciferae.[68]

Brontispa longissima (coconut leaf beetle) feeds on young leaves, and damages both seedlings and mature coconut palms. In 2007, the Philippines imposed a quarantine in Metro Manila and 26 provinces to stop the spread of the pest and protect the Philippine coconut industry managed by some 3.5 million farmers.[69]

The fruit may also be damaged by eriophyid coconut mites (Eriophyes guerreronis). This mite infests coconut plantations, and is devastating; it can destroy up to 90% of coconut production. The immature seeds are infested and desapped by larvae staying in the portion covered by the perianth of the immature seed; the seeds then drop off or survive deformed. Spraying with wettable sulfur 0.4% or with Neem-based pesticides can give some relief, but is cumbersome and labor-intensive.

In Kerala, India, the main coconut pests are the coconut mite, the rhinoceros beetle, the red palm weevil, and the coconut leaf caterpillar. Research into countermeasures to these pests has as of 2009 yielded no results; researchers from the Kerala Agricultural University and the Central Plantation Crop Research Institute, Kasaragode, continue to work on countermeasures. The Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Kannur under Kerala Agricultural University has developed an innovative extension approach called the compact area group approach to combat coconut mites.

Production and cultivation

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) |

|---|---|

| 18.6 | |

| 14.7 | |

| 11.7 | |

| 2.6 | |

| 2.5 | |

| 1.2 | |

| World | 61.9 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[70] | |

In 2018, world production of coconuts was 62 million tonnes, led by Indonesia, the Philippines, and India, with 74% combined of the total (table).

Cultivation

Coconut palms are normally cultivated in hot and wet tropical climates. They need year round warmth and moisture to grow well and fruit. Coconut palms are hard to establish in dry climates, and cannot grow there without frequent irrigation; in drought conditions, the new leaves do not open well, and older leaves may become desiccated; fruit also tends to be shed.[52]

The extent of cultivation in the tropics is threatening a number of habitats, such as mangroves; an example of such damage to an ecoregion is in the Petenes mangroves of the Yucatán.[71]

Cultivars

Coconut has a number of commercial and traditional cultivars. They can be sorted mainly into tall cultivars, dwarf cultivars, and hybrid cultivars (hybrids between talls and dwarfs). Some of the dwarf cultivars such as 'Malayan dwarf' have shown some promising resistance to lethal yellowing, while other cultivars such as 'Jamaican tall' are highly affected by the same plant disease. Some cultivars are more drought resistant such as 'West coast tall' (India) while others such as 'Hainan Tall' (China) are more cold tolerant. Other aspects such as seed size, shape and weight, and copra thickness are also important factors in the selection of new cultivars. Some cultivars such as 'Fiji dwarf' form a large bulb at the lower stem and others are cultivated to produce very sweet coconut water with orange-coloured husks (king coconut) used entirely in fruit stalls for drinking (Sri Lanka, India).

Harvesting

In some parts of the world (Thailand and Malaysia), trained pig-tailed macaques are used to harvest coconuts. Thailand has been raising and training pig-tailed macaques to pick coconuts for around 400 years.[72] Training schools for pig-tailed macaques still exist both in southern Thailand and in the Malaysian state of Kelantan.[73]

Substitutes for cooler climates

In cooler climates (but not less than USDA Zone 9), a similar palm, the queen palm (Syagrus romanzoffiana), is used in landscaping. Its fruits are similar to the coconut, but smaller. The queen palm was originally classified in the genus Cocos along with the coconut, but was later reclassified in Syagrus. A recently discovered palm, Beccariophoenix alfredii from Madagascar, is nearly identical to the coconut, more so than the queen palm and can also be grown in slightly cooler climates than the coconut palm. Coconuts can only be grown in temperatures above 18 °C (64 °F) and need a daily temperature above 22 °C (72 °F) to produce fruit.

Production by country

Indonesia

In 2010, Indonesia increased its coconut production. It is now the world's largest producer of coconuts. The gross production was 15 million tonnes.[74] A sprouting coconut seed is the logo for Gerakan Pramuka Indonesia, the Indonesian scouting organization. It can be seen on all the scouting paraphernalia that elementary school children wear, as well as on the scouting pins and flags.[75]

Philippines

The Philippines is the world's second-largest producer of coconuts. It was the world's largest producer for decades until a decline in production due to aging trees as well as typhoon devastation. Indonesia overtook it in 2010. It is still the largest producer of coconut oil and copra, accounting for 64% of the global production. The production of coconuts plays an important role in the economy, with 25% of cultivated land (around 3.56 million hectares) used for coconut plantations and approximately 25 to 33% of the population reliant on coconuts for their livelihood.[76][77][78]

Two important coconut products were first developed in the Philippines, macapuno and nata de coco. Macapuno is a coconut variety with a jelly-like coconut meat. Its meat is sweetened, cut into strands, and sold in glass jars as coconut strings, sometimes labeled as "gelatinous mutant coconut". Nata de coco, also called coconut gel, is another jelly-like coconut product made from fermented coconut water.[79][80]

India

Traditional areas of coconut cultivation in India are the states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Puducherry, Andhra Pradesh, Goa, Maharashtra, Odisha, West Bengal and, Gujarat and the islands of Lakshadweep and Andaman and Nicobar. As per 2014–15 statistics from Coconut Development Board of Government of India, four southern states combined account for almost 90% of the total production in the country: Tamil Nadu (33.84%), Karnataka (25.15%), Kerala (23.96%), and Andhra Pradesh (7.16%).[81] Other states, such as Goa, Maharashtra, Odisha, West Bengal, and those in the northeast (Tripura and Assam) account for the remaining productions. Though Kerala has the largest number of coconut trees, in terms of production per hectare, Tamil Nadu leads all other states. In Tamil Nadu, Coimbatore and Tirupur regions top the production list.[82]

In Goa, the coconut tree has been reclassified by the government as a palm (like a grass), enabling farmers and real estate developers to clear land with fewer restrictions.[83] With this, it will no more be considered as a tree and no permission will be required by the forest department before cutting a coconut tree.[84]

Maldives

The coconut is the national tree of the Maldives and is considered the most important plant in the country. A coconut tree is also included in the country's national emblem and coat of arms. Coconut trees are grown on all the islands. Before modern construction methods were introduced, coconut leaves were used as roofing material for many houses in the islands, while coconut timber was used to build houses and boats.

Middle East

The main coconut-producing area in the Middle East is the Dhofar region of Oman, but they can be grown all along the Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, and Red Sea coasts, because these seas are tropical and provide enough humidity (through seawater evaporation) for coconut trees to grow. The young coconut plants need to be nursed and irrigated with drip pipes until they are old enough (stem bulb development) to be irrigated with brackish water or seawater alone, after which they can be replanted on the beaches. In particular, the area around Salalah maintains large coconut plantations similar to those found across the Arabian Sea in Kerala. The reasons why coconut are cultivated only in Yemen's Al Mahrah and Hadramaut governorates and in the Sultanate of Oman, but not in other suitable areas in the Arabian Peninsula, may originate from the fact that Oman and Hadramaut had long dhow trade relations with Burma, Malaysia, Indonesia, East Africa, and Zanzibar, as well as southern India and China. Omani people needed the coir rope from the coconut fiber to stitch together their traditional seagoing dhow vessels in which nails were never used. The knowhow of coconut cultivation and necessary soil fixation and irrigation may have found its way into Omani, Hadrami and Al-Mahra culture by people who returned from those overseas areas.

The coconut cultivars grown in Oman are generally of the drought-resistant Indian 'West Coast tall' variety. Unlike the UAE, which grows mostly non-native dwarf or hybrid coconut cultivars imported from Florida for ornamental purposes, the slender, tall Omani coconut cultivars are relatively well-adapted to the Middle East's hot dry seasons, but need longer to reach maturity. The Middle East's hot, dry climate favors the development of coconut mites, which cause immature seed dropping and may cause brownish-gray discoloration on the coconut's outer green fiber.

The ancient coconut groves of Dhofar were mentioned by the medieval Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta in his writings, known as Al Rihla.[85] The annual rainy season known locally as khareef or monsoon makes coconut cultivation easy on the Arabian east coast.

Coconut trees also are increasingly grown for decorative purposes along the coasts of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia with the help of irrigation. The UAE has, however, imposed strict laws on mature coconut tree imports from other countries to reduce the spread of pests to other native palm trees, as the mixing of date and coconut trees poses a risk of cross-species palm pests, such as rhinoceros beetles and red palm weevils.[86] The artificial landscaping may have been the cause for lethal yellowing, a viral coconut palm disease that leads to the death of the tree. It is spread by host insects, that thrive on heavy turf grasses. Therefore, heavy turf grass environments (beach resorts and golf courses) also pose a major threat to local coconut trees. Traditionally, dessert banana plants and local wild beach flora such as Scaevola taccada and Ipomoea pes-caprae were used as humidity-supplying green undergrowth for coconut trees, mixed with sea almond and sea hibiscus. Due to growing sedentary lifestyles and heavy-handed landscaping, a decline in these traditional farming and soil-fixing techniques has occurred.

United States

In the United States, coconut palms can be grown and reproduced outdoors without irrigation in Hawaii, southern and central Florida,[87] and the territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands.

In Florida, wild populations of coconut palms extend up the East Coast from Key West to Jupiter Inlet, and up the West Coast from Marco Island to Sarasota. Many of the smallest coral islands in the Florida Keys are known to have abundant coconut palms sprouting from coconuts that have drifted or been deposited by ocean currents. Coconut palms are cultivated north of south Florida to roughly Cocoa Beach on the East Coast and Clearwater on the West Coast.

Australia

Coconuts are commonly grown around the northern coast of Australia, and in some warmer parts of New South Wales. However they are mainly present as decoration, and the Australian coconut industry is small; Australia is a net importer of coconut products. Australian cities put much effort into de-fruiting decorative coconut trees to ensure that the mature coconuts do not fall and injure people.[88]

Uses

.jpg)

The coconut palm is grown throughout the tropics for decoration, as well as for its many culinary and nonculinary uses; virtually every part of the coconut palm can be used by humans in some manner and has significant economic value. Coconuts' versatility is sometimes noted in its naming. In Sanskrit, it is kalpa vriksha ("the tree which provides all the necessities of life"). In the Malay language, it is pokok seribu guna ("the tree of a thousand uses"). In the Philippines, the coconut is commonly called the "tree of life".[89]

It is one of the most useful trees in the world.[48]

Culinary uses

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 354 kcal (1,480 kJ) |

15.23 g | |

| Sugars | 6.23 g |

| Dietary fiber | 9.0 g |

33.49 g | |

| Saturated | 29.698 g |

| Monounsaturated | 1.425 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 0.366 g |

3.33 g | |

| Tryptophan | 0.039 g |

| Threonine | 0.121 g |

| Isoleucine | 0.131 g |

| Leucine | 0.247 g |

| Lysine | 0.147 g |

| Methionine | 0.062 g |

| Cystine | 0.066 g |

| Phenylalanine | 0.169 g |

| Tyrosine | 0.103 g |

| Valine | 0.202 g |

| Arginine | 0.546 g |

| Histidine | 0.077 g |

| Alanine | 0.170 g |

| Aspartic acid | 0.325 g |

| Glutamic acid | 0.761 g |

| Glycine | 0.158 g |

| Proline | 0.138 g |

| Serine | 0.172 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 6% 0.066 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.020 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 4% 0.540 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 6% 0.300 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 4% 0.054 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 7% 26 μg |

| Vitamin C | 4% 3.3 mg |

| Vitamin E | 2% 0.24 mg |

| Vitamin K | 0% 0.2 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 14 mg |

| Copper | 22% 0.435 mg |

| Iron | 19% 2.43 mg |

| Magnesium | 9% 32 mg |

| Manganese | 71% 1.500 mg |

| Phosphorus | 16% 113 mg |

| Potassium | 8% 356 mg |

| Selenium | 14% 10.1 μg |

| Sodium | 1% 20 mg |

| Zinc | 12% 1.10 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 47 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Per 100-gram serving with 354 calories, raw coconut meat supplies a high amount of total fat (33 grams), especially saturated fat (89% of total fat), moderate content of carbohydrates (15 grams), and protein (3 grams). Micronutrients in significant content (more than 10% of the Daily Value) include the dietary minerals, manganese, copper, iron, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc (table). The various parts of the coconut have a number of culinary uses.

Flaked coconut

The white, fleshy part of the seed, the coconut meat, is used fresh or dried in cooking, especially in confections and desserts such as macaroons and buko pie. Dried coconut is also used as the filling for many chocolate bars. Some dried coconut is purely coconut, but others are manufactured with other ingredients, such as sugar, propylene glycol, salt, and sodium metabisulfite. Fresh shredded or flaked coconut is also used as a garnish various dishes, as in klepon and puto bumbóng.[90]

Macapuno

A special cultivar of coconut known as macapuno has a jelly-like coconut meat. It was first developed for commercial cultivation in the Philippines and is used widely in Philippine cuisine for desserts, drinks, and pastries. It is also popular in Indonesia (where it is known as kopyor) for making beverages.[80]

Coconut milk

Coconut milk, not to be confused with coconut water, is obtained by pressing the grated coconut meat, usually with hot water added which extracts the coconut oil, proteins, and aromatic compounds. It is used for cooking various dishes. Coconut milk contains 5% to 20% fat, while coconut cream contains around 20% to 50% fat.[91][92] Most of which (89%) is saturated fat, with lauric acid as a major fatty acid.[93] Coconut milk can be diluted to create coconut milk beverages. These have much lower fat content and are suitable as milk substitutes.[91][92] The milk can be used to produce virgin coconut oil by controlled heating and removal of the oil fraction.

Coconut milk powder, a protein-rich powder can be processed from coconut milk following centrifugation, separation, and spray drying.[94]

Coconut milk and coconut cream extracted from grated coconut is frequently added to various dessert and savory dishes, as well as in curries and stews.[95][96] It can also be diluted into a beverage. Various other products made from thickened coconut milk with sugar and/or eggs like coconut jam and coconut custard are also widespread in Southeast Asia.[97][98] In the Philippines, sweetened reduced coconut milk is marketed as coconut syrup and is used for various desserts.[99] Coconut oil extracted from coconut milk or copra is also used for frying, cooking, and making margarine, among other uses.[95][100]

Coconut water

Coconut water serves as a suspension for the endosperm of the coconut during its nuclear phase of development. Later, the endosperm matures and deposits onto the coconut rind during the cellular phase.[47] It is consumed throughout the humid tropics, and has been introduced into the retail market as a processed sports drink. Mature fruits have significantly less liquid than young, immature coconuts, barring spoilage. Coconut water can be fermented to produce coconut vinegar.

Per 100-gram serving, coconut water contains 19 calories and no significant content of essential nutrients.

Coconut water can be drunk fresh or used in cooking as in binakol.[101][102] It can also be fermented to produce a jelly-like dessert known as nata de coco.[79]

Coconut flour

Coconut flour has also been developed for use in baking, to combat malnutrition.[95]

Coconut oil

Another product of the coconut is coconut oil. It is commonly used in cooking, especially for frying. It can be used in liquid form as would other vegetable oils, or in solid form as would butter or lard.

Coconut butter

Coconut butter is often used to describe solidified coconut oil, but has also been adopted as an alternate name for creamed coconut, a specialty products made of coconut milk solids or puréed coconut meat and oil.[90] Coconut chips, made from oven-baked coconut meat, have been sold in the tourist regions of Hawaii and the Caribbean.[103]

Heart of palm

Apical buds of adult plants are edible, and are known as "palm cabbage" or heart of palm. They are considered a rare delicacy, as harvesting the buds kills the palms. Hearts of palm are eaten in salads, sometimes called "millionaire's salad".

Sprouted coconut

Newly germinated coconuts contain an edible fluff of marshmallow-like consistency called sprouted coconut or coconut sprout, produced as the endosperm nourishes the developing embryo. It is a haustorium, a spongy absorbent tissue formed from the distal portion of embryo during coconut germination, facilitates absorption of nutrients for the growing shoot and root.[104]

Toddy and sap

The sap derived from incising the flower clusters of the coconut is drunk as neera, also known as toddy or tubâ (Philippines), tuak (Indonesia and Malaysia) or karewe (fresh and not fermented, collected twice a day, for breakfast and dinner) in Kiribati. When left to ferment on its own, it becomes palm wine. Palm wine is distilled to produce arrack. In the Philippines, this alcoholic drink is called lambanog or "coconut vodka".[105]

The sap can be reduced by boiling to create a sweet syrup or candy such as te kamamai in Kiribati or dhiyaa hakuru and addu bondi in the Maldives. It can be reduced further to yield coconut sugar also referred to as palm sugar or jaggery. A young, well-maintained tree can produce around 300 litres (66 imp gal; 79 US gal) of toddy per year, while a 40-year-old tree may yield around 400 litres (88 imp gal; 110 US gal).[106]

Coconut sap, usually extracted from cut inflorescence stalks is sweet when fresh and can be drunk as is like in tuba fresca of Mexico.[107] They can also be processed to extract palm sugar.[108] The sap when fermented can also be made into coconut vinegar or various palm wines (which can be further distilled to make arrack).[109][110]

Coir

Coir (the fiber from the husk of the coconut) is used in ropes, mats, doormats, brushes, and sacks, as caulking for boats, and as stuffing fiber for mattresses.[111] It is used in horticulture in potting compost, especially in orchid mix. The coir is used to make brooms in Cambodia.[112]

Copra

Copra is the dried meat of the seed and after processing produces coconut oil and coconut meal. Coconut oil, aside from being used in cooking as an ingredient and for frying, is used in soaps, cosmetics, hair oil, and massage oil. Coconut oil is also a main ingredient in Ayurvedic oils. In Vanuatu, coconut palms for copra production are generally spaced 9 m (30 ft) apart, allowing a tree density of 100 to 160 per hectare (40 to 65 per acre).

Husks and shells

The husk and shells can be used for fuel and are a source of charcoal.[113] Activated carbon manufactured from coconut shell is considered extremely effective for the removal of impurities. The coconut's obscure origin in foreign lands led to the notion of using cups made from the shell to neutralise poisoned drinks. The cups were frequently engraved and decorated with precious metals.[114]

A dried half coconut shell with husk can be used to buff floors. It is known as a bunot in the Philippines and simply a "coconut brush" in Jamaica. The fresh husk of a brown coconut may serve as a dish sponge or body sponge. A coco chocolatero was a cup used to serve small quantities of beverages (such as chocolate drinks) between the 17th and 19th centuries in countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, and Venezuela.

In Asia, coconut shells are also used as bowls and in the manufacture of various handicrafts, including buttons carved from dried shell. Coconut buttons are often used for Hawaiian aloha shirts. Tempurung, as the shell is called in the Malay language, can be used as a soup bowl and—if fixed with a handle—a ladle. In Thailand, the coconut husk is used as a potting medium to produce healthy forest tree saplings. The process of husk extraction from the coir bypasses the retting process, using a custom-built coconut husk extractor designed by ASEAN–Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre in 1986. Fresh husks contain more tannin than old husks. Tannin produces negative effects on sapling growth.[115] In parts of South India, the shell and husk are burned for smoke to repel mosquitoes.

.jpg)

Half coconut shells are used in theatre Foley sound effects work, struck together to create the sound effect of a horse's hoofbeats. Dried half shells are used as the bodies of musical instruments, including the Chinese yehu and banhu, along with the Vietnamese đàn gáo and Arabo-Turkic rebab. In the Philippines, dried half shells are also used as a music instrument in a folk dance called maglalatik.

The shell, freed from the husk, and heated on warm ashes, exudes an oily material that is used to soothe dental pains in traditional medicine of Cambodia.[112]

In World War II, coastwatcher scout Biuku Gasa was the first of two from the Solomon Islands to reach the shipwrecked and wounded crew of Motor Torpedo Boat PT-109 commanded by future U.S. president John F. Kennedy. Gasa suggested, for lack of paper, delivering by dugout canoe a message inscribed on a husked coconut shell, reading “Nauru Isl commander / native knows posit / he can pilot / 11 alive need small boat / Kennedy.”[116] This coconut was later kept on the president's desk, and is now in the John F. Kennedy Library.[117]

Leaves

The stiff midribs of coconut leaves are used for making brooms in India, Indonesia (sapu lidi), Malaysia, the Maldives, and the Philippines (walis tingting). The green of the leaves (lamina) is stripped away, leaving the veins (long, thin, woodlike strips) which are tied together to form a broom or brush. A long handle made from some other wood may be inserted into the base of the bundle and used as a two-handed broom.

The leaves also provide material for baskets that can draw well water and for roofing thatch; they can be woven into mats, cooking skewers, and kindling arrows as well. Leaves are also woven into small piuches that are filled with rice and cooked to make pusô and ketupat.[118]

Dried coconut leaves can be burned to ash, which can be harvested for lime. In India, the woven coconut leaves are used to build wedding marquees, especially in the states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

The leaves are used for thatching houses, or for decorating climbing frames and meeting rooms in Cambodia, where the plant is known as dôô:ng.[112]

Timber

Coconut trunks are used for building small bridges and huts; they are preferred for their straightness, strength, and salt resistance. In Kerala, coconut trunks are used for house construction. Coconut timber comes from the trunk, and is increasingly being used as an ecologically sound substitute for endangered hardwoods. It has applications in furniture and specialized construction, as notably demonstrated in Manila's Coconut Palace.

Hawaiians hollowed the trunk to form drums, containers, or small canoes. The "branches" (leaf petioles) are strong and flexible enough to make a switch. The use of coconut branches in corporal punishment was revived in the Gilbertese community on Choiseul in the Solomon Islands in 2005.[119]

Roots

The roots are used as a dye, a mouthwash, and a folk medicine for diarrhea and dysentery.[42] A frayed piece of root can also be used as a toothbrush. In Cambodia, the roots are used in traditional medicine as a treatment for dysentery.[112]

Other uses

The leftover fiber from coconut oil and coconut milk production, coconut meal, is used as livestock feed. The dried calyx is used as fuel in wood-fired stoves. Coconut water is traditionally used as a growth supplement in plant tissue culture and micropropagation.[120] The smell of coconuts comes from the 6-pentyloxan-2-one molecule, known as δ-decalactone in the food and fragrance industries.[121]

Tool and shelter for animals

Researchers from the Melbourne Museum in Australia observed the octopus species Amphioctopus marginatus use tools, specifically coconut shells, for defense and shelter. The discovery of this behavior was observed in Bali and North Sulawesi in Indonesia between 1998 and 2008.[122][123][124] Amphioctopus marginatus is the first invertebrate known to be able to use tools.[123][125]

A coconut can be hollowed out and used as a home for a rodent or small birds. Halved, drained coconuts can also be hung up as bird feeders, and after the flesh has gone, can be filled with fat in winter to attract tits.

Allergies

Food allergies

Coconut oil is increasingly used in the food industry.[126] Proteins from coconut may cause food allergy, including anaphylaxis.[126]

In the United States, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration declared that coconut must be disclosed as an ingredient on package labels as a "tree nut" with potential allergenicity.[127]

Topical allergies

Cocamidopropyl betaine (CAPB) is a surfactant manufactured from coconut oil that is increasingly used as an ingredient in personal hygiene products and cosmetics, such as shampoos, liquid soaps, cleansers and antiseptics, among others.[128] CAPB may cause mild skin irritation,[128] but allergic reactions to CAPB are rare[129] and probably related to impurities rendered during the manufacturing process (which include amidoamine and dimethylaminopropylamine) rather than CAPB itself.[128]

In culture

The coconut was a critical food item for the people of Polynesia, and the Polynesians brought it with them as they spread to new islands.[130]

In the Ilocos region of the northern Philippines, the Ilocano people fill two halved coconut shells with diket (cooked sweet rice), and place liningta nga itlog (halved boiled egg) on top of it. This ritual, known as niniyogan, is an offering made to the deceased and one's ancestors. This accompanies the palagip (prayer to the dead).

A coconut (Sanskrit: narikela) is an essential element of rituals in Hindu tradition.[131] Often it is decorated with bright metal foils and other symbols of auspiciousness. It is offered during worship to a Hindu god or goddess. Narali Purnima is celebrated on a full moon day which usually signifies the end of monsoon season in India. The word ‘Narali’ is derived from naral implying ‘coconut’ in Marathi. Fishermen give an offering of coconut to the sea to celebrate the beginning of a new fishing season.[132] Irrespective of their religious affiliations, fishermen of India often offer it to the rivers and seas in the hopes of having bountiful catches. Hindus often initiate the beginning of any new activity by breaking a coconut to ensure the blessings of the gods and successful completion of the activity. The Hindu goddess of well-being and wealth, Lakshmi, is often shown holding a coconut.[133] In the foothills of the temple town of Palani, before going to worship Murugan for the Ganesha, coconuts are broken at a place marked for the purpose. Every day, thousands of coconuts are broken, and some devotees break as many as 108 coconuts at a time as per the prayer. They are also used in Hindu weddings as a symbol of prosperity.[134]

The flowers are used sometimes in wedding ceremonies in Cambodia.[112]

The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club of New Orleans traditionally throws hand-decorated coconuts, one of the most valuable Mardi Gras souvenirs, to parade revelers. The tradition began in the 1910s, and has continued since. In 1987, a "coconut law" was signed by Governor Edwin Edwards exempting from insurance liability any decorated coconut "handed" from a Zulu float.[135]

The coconut is also used as a target and prize in the traditional British fairground game coconut shy. The player buys some small balls which are then thrown as hard as possible at coconuts balanced on sticks. The aim is to knock a coconut off the stand and win it.[136]

It was the main food of adherents of the now discontinued Vietnamese religion Đạo Dừa.[137]

Myths and legends

Some South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Pacific Ocean cultures have origin myths in which the coconut plays the main role. In the Hainuwele myth from Maluku, a girl emerges from the blossom of a coconut tree.[138] In Maldivian folklore, one of the main myths of origin reflects the dependence of the Maldivians on the coconut tree.[139] In the story of Sina and the Eel, the origin of the coconut is related as the beautiful woman Sina burying an eel, which eventually became the first coconut.[140]

According to urban legend, more deaths are caused by falling coconuts than by sharks annually.[141]

See also

- Domesticated plants and animals of Austronesia

- Central Plantation Crops Research Institute

- Coconut production in Kerala

- Coir Board of India

- List of coconut dishes

- List of dishes made using coconut milk

- Ravanahatha – a musical instrument sometimes made of coconuts

- Voanioala gerardii – forest coconut, the closest relative of the modern coconut

References

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Cocos. World Checklist of Selected Plant Families.

- J. Pearsall, ed. (1999). "Coconut". Concise Oxford Dictionary (10th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-860287-1.

- Michaels, Axel. (2006) [2004]. Hinduism : past and present. Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-2776-9. OCLC 398164072.

- Dalgado, Sebastião (1982). Glossário luso-asiático. 1. p. 291. ISBN 9783871184796. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016.

- "coco | Origin and meaning of coco by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "coconut | Origin and meaning of coconut by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Losada, Fernando Díez. (2004). La tribuna del idioma. Editorial Tecnologica de CR. p. 481 Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-9977-66-161-2. (in Spanish)

- Figueiredo, Cândido. (1940). Pequeno Dicionário da Lingua Portuguesa. Livraria Bertrand. Lisboa. (in Portuguese)

- Elzebroek, A.T.G. and Koop Wind (Eds.). (2008). Guide to Cultivated Plants. CABI. pp. 186–192 Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-1-84593-356-2.

- Grimwood 1975, p. 1 Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- Werth, E. (1933). Distribution, Origin and Cultivation of the Coconut Palm. Ber. Deutschen Bot. Ges., vol 51, pp. 301–304. (article translated into English by Dr. R. Child, Director, Coconut Research Scheme, Lunuwila, Sri Lanka).

- Roger Blench; Matthew Spriggs (1998). Archaeology and Language: Correlating archaeological and linguistic hypotheses. Routledge. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-415-11761-6.

- Rosengarten, Frederic Jr. (2004). The Book of Edible Nuts. Dover Publications. pp. 65–93 Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-486-43499-5.

- "The Fifth Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman – The Arabian Nights – The Thousand and One Nights – Sir Richard Burton translator". Classiclit.about.com. November 2, 2009. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- Antonio Pigafetta; translated by James Alexander Robertson (1906). Magellan's Voyage Around the World, Volume 1. Arthur H. Clark Company. pp. 64–100. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016.

- Chambers, Geoff (2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians". eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- Blench, Roger (2009). "Remapping the Austronesian expansion" (PDF). In Evans, Bethwyn (ed.). Discovering History Through Language: Papers in Honour of Malcolm Ross. Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 9780858836051.

- Cook, Orator Fuller (1901). "History of the Coconut Palm in America" (PDF). Contributions from the National Herbarium. 7: 257–293.

- Dowe JL, Smith LT (2002). "A Brief History of the Coconut Palm in Australia" (PDF). Palms. 46 (3). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 30, 2016.

- Gunn, Bee F.; Baudouin, Luc; Olsen, Kenneth M.; Ingvarsson, Pär K. (June 22, 2011). "Independent Origins of Cultivated Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in the Old World Tropics". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e21143. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621143G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021143. PMC 3120816. PMID 21731660.

- Lutz, Diana (June 24, 2011). "Deep history of coconuts decoded". The Source. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Brouwers, Lucas (August 1, 2011). "Coconuts: not indigenous, but quite at home nevertheless". Scientific American. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Perera, Lalith, Suriya A.C.N. Perera, Champa K. Bandaranayake and Hugh C. Harries. (2009). "Chapter 12 – Coconut". In Johann Vollmann and Istvan Rajcan (Eds.). Oil Crops. Springer. pp. 370–372 Archived April 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-387-77593-7.

- Elevitch, C.R., ed. (April 2006). "Cocos nucifera (coconut), version 2.1" (PDF). In: Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Permanent Agriculture Resources, Hōlualoa, Hawai‘i. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- Baudouin, Luc; Lebrun, Patricia (July 26, 2008). "Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) DNA studies support the hypothesis of an ancient Austronesian migration from Southeast Asia to America". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 56 (2): 257–262. doi:10.1007/s10722-008-9362-6.

- Crowther, Alison; Lucas, Leilani; Helm, Richard; Horton, Mark; Shipton, Ceri; Wright, Henry T.; Walshaw, Sarah; Pawlowicz, Matthew; Radimilahy, Chantal; Douka, Katerina; Picornell-Gelabert, Llorenç; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Boivin, Nicole L. (June 14, 2016). "Ancient crops provide first archaeological signature of the westward Austronesian expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (24): 6635–6640. doi:10.1073/pnas.1522714113. PMC 4914162. PMID 27247383.

- Ahuja, SC; Ahuja, Siddharta; Ahuja, Uma (2014). "Coconut – History, Uses, and Folklore" (PDF). Asian Agri-History. 18 (3): 223. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- Elevitch, Craig R., ed. (2006). Traditional trees of Pacific Islands : their culture, environment, and use. forewords by Isabella Aiona Abbott and Roger R.B. Leakey (1st ed.). Hōlualoa, Hawaii: Permanent Agriculture Resources. ISBN 978-0970254450.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0415100540.

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Johns, D. A.; Irwin, G. J.; Sung, Y. K. (September 29, 2014). "An early sophisticated East Polynesian voyaging canoe discovered on New Zealand's coast". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (41): 14728–14733. doi:10.1073/pnas.1408491111. PMC 4205625. PMID 25267657.

- Ward, R. G.; Brookfield, M. (1992). "Special Paper: the dispersal of the coconut: did it float or was it carried to Panama?". Journal of Biogeography. 19 (5): 467–480. doi:10.2307/2845766. JSTOR 2845766.

- Harries, Hugh C.; Clement, Charles R. (March 1, 2014). "Long-distance dispersal of the coconut palm by migration within the coral atoll ecosystem". Annals of Botany. 113 (4): 565–570. doi:10.1093/aob/mct293. ISSN 0305-7364.

- Srivastava, Rashmi; Srivastava, Gaurav (2014). "Fossil fruit of Cocos L. (Arecaceae) from Maastrichtian-Danian sediments of central India and its phytogeographical significance". Acta Palaeobotanica. 54 (1): 67–75. doi:10.2478/acpa-2014-0003.

- Nayar, N. Madhavan (2016). The Coconut: Phylogeny, Origins, and Spread. Academic Press. pp. 51–66. ISBN 9780128097793.

- Conran, John G.; Bannister, Jennifer M.; Lee, Daphne E.; Carpenter, Raymond J.; Kennedy, Elizabeth M.; Reichgelt, Tammo; Fordyce, R. Ewan (2015). "An update of monocot macrofossil data from New Zealand and Australia". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 178 (3): 394–420. doi:10.1111/boj.12284.

- Endt, D.; Hayward, B. (1997). "Modern relatives of New Zealand's fossil coconuts from high altitude South America". New Zealand Geological Society Newsletter. 113: 67–70.

- Hayward, Bruce (2012). "Fossil Oligocene coconut from Northland". Geocene. 7 (13).

- Singh, Hukam; Shukla, Anumeha; Mehrotra, R.C. (2016). "A Fossil Coconut Fruit from the Early Eocene of Gujarat". Journal of Geological Society of India. 87 (3). Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- T. Pradeepkumar, B. Sumajyothibhaskar, and K.N. Satheesan. (2008). Management of Horticultural Crops (Horticulture Science Series Vol.11, 2nd of 2 Parts). New India Publishing. pp. 539–587 Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-81-89422-49-3.

- Grimwood BE, Ashman F (1975). Coconut Palm Products: Their Processing in Developing Countries. United Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 1. ISBN 9789251008539. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016.

- Sarian, Zac B. (August 18, 2010). New coconut yields high Archived November 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Manila Bulletin. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- Ravi, Rajesh. (March 16, 2009). Rise in coconut yield, farming area put India on top Archived May 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Financial Express. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- "How Long Does It Take for a Coconut Tree to Get Coconuts?". Home Guides – SF Gate. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014.

- "Coconut Varieties". floridagardener.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- "Coconut botany". Agritech Portal, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University. December 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- "Cocos nucifera L. (Source: James A. Duke. 1983. Handbook of Energy Crops; unpublished)". Purdue University, NewCROP – New Crop Resource. 1983. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Bourke, R. Michael and Tracy Harwood (Eds.). (2009). Food and Agriculture in Papua New Guinea. Australian National University. p. 327 Archived April 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-1-921536-60-1.

- Thampan, P.K. (1981). Handbook on Coconut Palm. Oxford & IBH Publishing Co.

- Willmer, Pat. (2011). Pollination and Floral Ecology. Princeton University Press. p. 57 Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-691-12861-0.

- Chan, Edward and Craig R. Elevitch. (April 2006). Cocos nucifera (coconut) Archived October 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (version 2.1). In C. R. Elevitch (ed.). Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Hōlualoa, Hawai‘i: Permanent Agriculture Resources (PAR).

- Harries, H. C. (2012). "Germination rate is the significant characteristic determining coconut palm diversity". Annals of Botany. 2012: pls045. doi:10.1093/aobpla/pls045. PMC 3532018. PMID 23275832.

- Lebrun, P.; Seguin, M.; Grivet, L.; Baudouin, L. (1998). "Genetic diversity in coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) revealed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) markers". Euphytica. 101: 103–108. doi:10.1023/a:1018323721803.

- Shukla, A.; Mehrotra, R. C.; Guleria, J. S. (2012). "Cocos sahnii Kaul: A Cocos nucifera L.-like fruit from the Early Eocene rainforest of Rajasthan, western India". Journal of Biosciences. 37 (4): 769–776. doi:10.1007/s12038-012-9233-3. PMID 22922201.

- Santos, G.A., Batugal, P.A., Othman, A., Baudouin, L., and Labouisse J.P. 1996. Manual on standardised techniques in coconut breeding. IPGRI–COGENT publication. Stamford Press, Singapore. Accessed at bioversityinternational.org Archived December 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Harries, H. C. (1978). "The evolution, dissemination and classification of Cocos nucifera L.". The Botanical Review. 44 (3): 265–319. doi:10.1007/bf02957852.

- Huang, Y.-Y.; Matzke, A. J. M.; Matzke, M. (2013). "Complete sequence and comparative analysis of the chloroplast genome of coconut palm (Cocos nucifera)". PLOS One. 8 (8): e74736. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874736H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074736. PMC 3758300. PMID 24023703.

- Rivera, R.; Edwards, K. J.; Barker, J. H.; Arnold, G. M.; Ayad, G.; Hodgkin, T.; Karp, A. (1999). "Isolation and characterization of polymorphic microsatellites in Cocos nucifera L". Genome. 42 (4): 668–675. doi:10.1139/gen-42-4-668. PMID 10464790.

- Foale, Mike. (2003). The Coconut Odyssey – the bounteous possibilities of the tree of life Archived March 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Archived March 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- Edmondson, C.H. (1941). "Viability of coconut seeds after floating in sea". Bernice P. Bishop Museum Occasional Papers. 16: 293–304.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. (1950) Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft. Mattituck: Amereon House. 240 p.

- Wales, State Library of New South. "William Bligh's Logbook". Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- Gunn, Bee; Luc Baudouin; Kenneth M. Olsen (2011). "Independent Origins of Cultivated Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in the Old World Tropics". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e21143. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621143G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021143. PMC 3120816. PMID 21731660.

- Ferguson, John. (1898). All about the "coconut palm" (Cocos nucifera) (2nd edition).

- Harries, H.C.; Romney, D.H. (1974). "Maypan: an F1 hybrid coconut variety for commercial production in Jamaica". World Crops. 26: 110–111.

- Bourdeix, Ronald (December 9, 2016). "Clarion call for King Coconut". www.atimes.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- Yarro, J. G.; Otindo, B. L.; Gatehouse, A. G.; Lubega, M. C. (December 1981). "Dwarf variety of coconut, Cocos nucifera (Palmae), a hostplant for the African armyworm, Spodoptera exempta (Wlk.) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae)". International Journal of Tropical Insect Science. 1 (4): 361–362. doi:10.1017/S1742758400000667. ISSN 0191-9040.

- "Report: 26 provinces quarantined for coconut pest". GMA News Online. September 28, 2007. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- "Coconut production in 2018, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- McGinley, Mark; Hogan, C Michael (April 19, 2011). "Petenes mangroves: types and severity of threats". The Encyclopedia of Earth. World Wildlife Fund, Washington, DC. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- What's Funny About The Business Of Monkeys Picking Coconuts?, NPR, October 19, 2015.

- Bertrand, Mireille. (January 27, 1967). Training without Reward: Traditional Training of Pig-tailed Macaques as Coconut Harvesters. Science 155 (3761): 484–486.

- FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Archived November 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, FAO

- John S. Wilson (1959), Scouting Round the World. First edition, Blandford Press. p. 254

- Tacio, Henrylito D. "Reviving the Coconut Industry of the Philippines". Gaia Discovery. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Calderon, Justin. "Philippines counting on coconuts". investvine. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- McAloon, Catherine. "Coconut faces a looming global supply shortage, but could an Australian industry crack it?". ABC News. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Tietze, Harald; Echano, Arthur (2006). Coconut: Rediscovered as Medicinal Food. Harald Tietze Publishing P/. p. 37. ISBN 9781876173579. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- Rillo, Erlinda P. (1999). "Coconut embryo culture". In Oropeza, C.; Verdeil, J.L.; Ashburner, G.R.; Cardeña, R.; Santamaría, J.M. (eds.). Current Advances in Coconut Biotechnology. Current Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture. 35. Springer Netherlands. pp. 279–288. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-9283-3_20. ISBN 9789401592833.

- Coconut Development Board; Government of India. (n.d.). "Coconut Cultivation". Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- Coconut Development Board; Government of India. (n.d.). "Coconut Cultivation". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- "Indian state decides coconut trees are no longer trees but palms". The Guardian. January 20, 2016. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- "Coconut tree loses tree status in Goa – Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- Halsall, Paul. (Ed). (February 21, 2001). "Medieval Sourcebook: Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa 1325–1354". Fordham University Center for Medieval Studies. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- Kaakeh, Walid; El-Ezaby, Fouad; Aboul-Nour, Mahmoud M.; Khamis, Ahmed A. (2001). "Management of the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Oliv., by a pheromone/food-based trapping system" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- "Cocos nucifera, Coconut palm". FloridaGardener.com. Florida Gardener. June 12, 2008. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- "Australia has a lot of coconut palms — so why don't we have a coconut industry? - ABC News". www.abc.net.au. September 29, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Margolis, Jason. (December 13, 2006). Coconut fuel Archived August 31, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. PRI's The World. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- Roehl, E. (1996). Whole Food Facts: The Complete Reference Guide. Inner Traditions/Bear. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-89281-635-4. Archived from the original on November 23, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- NIIR Board of Consultants and Engineers (2006). The Complete Book on Coconut & Coconut Products (Cultivation and Processing). Asia Pacific Business Press Inc. p. 274. ISBN 9788178330075.

- Tetra Pak (2016). "The Chemistry of Coconut Milk and Cream". Coconut Handbook. Tetra Pak International S.A. ISBN 9789177739487.

- "Full Report (All Nutrients): 12117, Nuts, coconut milk, raw (liquid expressed from grated meat and water)". US Department of Agriculture, National Nutrient Database, version SR-28. 2015. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016.

- Naik A, Raghavendra SN, Raghavarao KS (2012). "Production of coconut protein powder from coconut wet processing waste and its characterization". Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 167 (5): 1290–302. doi:10.1007/s12010-012-9632-9. PMID 22434355.

- Grimwood, Brian E. (1975). Coconut Palm Products: Their Processing in Developing Countries. Food & Agriculture Organization. pp. 183–187. ISBN 9789251008539.

- Philippine Coconut Authority (2014). Coconut Processing Technologies: Coconut Milk (PDF). FPDD Guide No. 2 - Series of 2014. Department of Agriculture, Republic of the Philippines.

- Duruz, Jean; Khoo, Gaik Cheng (2014). Eating Together: Food, Space, and Identity in Malaysia and Singapore. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 45. ISBN 9781442227415.

- Alford, Jeffrey; Duguid, Naomi (2000). Hot Sour Salty Sweet: A Culinary Journey Through Southeast Asia. Artisan Books. p. 302. ISBN 9781579655648.

- Thampan, Palakasseril Kumaran (1981). Handbook on Coconut Palm. Oxford & IBH. p. 199.

- Kurian, Alice; Peter, K.V. (2007). Commercial Crops Technology. New India Publishing. pp. 202–203. ISBN 9788189422523.

- Janick J, Paull RE (2008). Cocos in The Encyclopedia of Fruit and Nuts. pp. 109–113. ISBN 9780851996387. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- "Ginataang Manok (Chicken Stewed in Coconut Milk) Filipino Recipe!". Savvy Nana's. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- Greaves-Gabbadon, Sarah. "Caribbean Plate: A Recipe For Coconut Chips From Jamaica". Caribbean Journal. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Manivannan, A; Bhardwaj, R; Padmanabhan, S; Suneja, P; Hebbar, K. B; Kanade, S. R (2018). "Biochemical and nutritional characterization of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) haustorium". Food Chemistry. 238: 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.127. PMID 28867086.

- Porter, Jolene V. (2005). "Lambanog: A Philippine Drink". Washington, D.C.: American University. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- Grimwood 1975, p. 20 Archived April 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- "Culture of Colima". Explorando Mexico. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- "Palm Sugar in Germany" (PDF). Import Promotion Desk (IPD). CBI, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Netherlands. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- Sanchez, Priscilla C. (2008). Philippine Fermented Foods: Principles and Technology. UP Press. pp. 151–153. ISBN 9789715425544.

- Gibbs, H.D.; Holmes, W.C. (1912). "The Alcohol Industry of the Philippine Islands Part II: Distilled Liquors; their Consumption and Manufacture". The Philippine Journal of Science: Section A. 7: 19–46.

- Grimwood 1975, p. 22 Archived April 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- Pauline Dy Phon (2000). Plants Utilised In Cambodia. Phnon Penh: Imprimerie Olympic. p. 165-6.

- "Coconut Shell Lump Charcoal". Supreme Carbon Indonesia. Archived from the original on December 29, 2012.

- "Hans van Amsterdam: Coconut Cup with Cover (17.190.622ab) – Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013.

- Somyos Kijkar. "Handbook: Coconut husk as a potting medium". ASEAN-Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre Project 1991, Muak-Lek, Saraburi, Thailand. ISBN 974-361-277-1.

- Edwards, Owen. "Remembering PT-109: A carved walking stick evokes ship commander John F. Kennedy's dramatic rescue at sea". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- "MO63.4852 Coconut shell paperweight with PT109 rescue message". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- Grimwood 1975, p. 19 Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- Herming, George. (March 6, 2006). Wagina whips offenders Archived October 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Solomon Star.

- Yong, JW. Ge L. Ng YF. Tan SN. (2009). "The chemical composition and biological properties of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) water". Molecules. 14 (12): 5144–64. doi:10.3390/molecules14125144. PMC 6255029. PMID 20032881.

- "Data sheet about delta-decalactone and its properties". Thegoodscentscompany.com. July 18, 2000. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- Finn, Julian K.; Tregenza, Tom; Norman, Mark D. (2009). "Defensive tool use in a coconut-carrying octopus". Curr. Biol. 19 (23): R1069–R1070. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.052. PMID 20064403.

- Gelineau, Kristen (December 15, 2009). "Aussie scientists find coconut-carrying octopus". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 18, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- Harmon, Katherine (December 14, 2009). "A tool-wielding octopus? This invertebrate builds armor from coconut halves". Scientific American. Archived from the original on December 17, 2009.

- Henderson, Mark (December 15, 2009). "Indonesia's veined octopus 'stilt walks' to collect coconut shells". Times Online. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011.

- Michavila Gomez A, Amat Bou M, Gonzalez Cortés MV, Segura Navas L, Moreno Palanques MA, Bartolomé B (2015). "Coconut anaphylaxis: Case report and review" (PDF). Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) (Review. Letter. Case reports.). 43 (2): 219–20. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2013.09.004. PMID 24231149. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 25, 2016.