Parashurama

Parashurama (Sanskrit: परशुराम, IAST: Paraśurāma, lit. Rama with an axe) is the sixth avatar of Vishnu in Hinduism and he is one of the chiranjeevis who will appear at the end of the Kali yuga to be the guru of Vishnu's tenth and last avatar Kalki . Born as a Brahmin, Parashurama carried traits of a Kshatriya and is often regarded as a Brahman Warrior, He carried a number of traits, which included aggression, warfare and valor; also, serenity, prudence and patience. Like other incarnations of Vishnu, he was foretold to appear at a time when overwhelming evil prevailed on the earth.The Kshatriya class, with weapons and power, had begun to abuse their power, take what belonged to others by force and tyrannize people. Parashurama corrects the cosmic equilibrium by destroying these Kshatriya warriors. Parashurama is also the Guru of Bhishma, Dronacharya, and Karna.[1][2]

| Parashurama | |

|---|---|

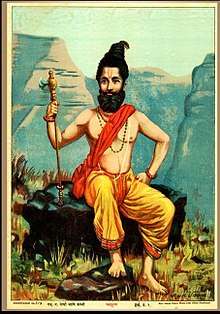

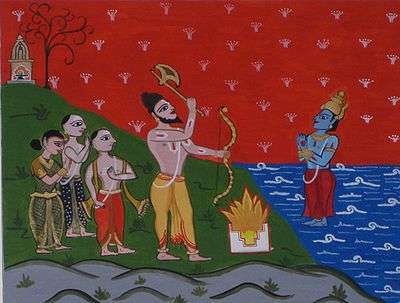

Parashurama with his axe (two representations) | |

| Other names | Bhàrgava rāma Jamadagnya rāma Rambhadra |

| Affiliation | Sixth Avatar of Vishnu, Vaishnavism |

| Weapon | Axe named Vidyudabhi (paraśhu) |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | |

He is also referred to as Rama Jamadagnya, Rama Bhargava and Veerarama in some Hindu texts.[3]

Legends

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Holy scriptures

|

|

Sampradayas

|

|

Related traditions |

|

|

According to Hindu legends, Parashurama was born to the Brahmin sage Jamadagni and his Kshatriya wife Renuka, living in a hut.[4] His birthplace is believed to be on top of the Janapav hills in Indore, Madhya Pradesh.[5][6] On top of the hills is a Shiva temple where Parshurama is believed to have worshipped Lord Shiva, the abbey (ashram) is known as Jamadagni Ashram, named after his father. The place also has a kund (pond) that is being developed by the state government.[7] They had a celestial cow called Surabhi which gives all they desire ( cow kamadhenu's daughter).[2][8] A king named Kartavirya Arjuna (not to be confused with Arjuna the Pandava)[9][note 1] – learns about it and wants it. He asks Jamadagni to give it to him, but the sage refuses. While Parashurama is away from the hut, the king takes it by force.[2] Parashurama learns about this crime, and is upset. With his axe in his hand, he challenges the king to battle. They fight, and Parushama kills the king, according to the Hindu history.[3] The warrior class challenges him, and he kills all his challengers. The legend likely has roots in the ancient conflict between the Brahmin varna, with knowledge duties, and the Kshatriya varna, with warrior and enforcement roles.[2][1][10]

In some versions of the legend, after his martial exploits, Parashurama returns to his sage father with the Surabhi cow and tells him about the battles he had to fight. The sage does not congratulate Parashurama, but reprimands him stating that a Brahmin should never kill a king. He asks him to expiate his sin by going on pilgrimage. After Parashurama returns from pilgrimage, he is told that while he was away, his father was killed by warriors seeking revenge. Parashurama again picks up his axe and kills many warriors in retaliation. In the end, he relinquishes his weapons and takes up Yoga.

In Kannada folklore, especially in devotional songs sung by the Devdasis he is often referred to as son of Yellamma.

Parasurama legends are notable for their discussion of violence, the cycles of retaliations, the impulse of krodha (anger), the inappropriateness of krodha, and repentance.[11][note 2]

Parasurama and origin of western coast(Konkan)

There are legends dealing with the origins of western coast geographically and culturally. One such legend is the retrieval of Western coast from the sea, by Parasurama, a warrior sage. It proclaims that Parasurama, an Avatar of Mahavishnu, threw His battle axe into the sea. As a result, the land of Western coast arose, and thus was reclaimed from the waters. In present-day Goa(or Gomantak), which is a part of the Konkan, there is a temple in Canacona in South Goa district dedicated to Lord Parshuram.[14][15][16]

Texts

He is generally presented as the fifth son of Renuka and rishi (seer) Jamadagni, states Thomas E Donaldson.[10] The legends of Parashurama appear in many Hindu texts, in different versions:[17]

- In chapter 6 of the Devi Bhagavata Purana, he is born from the thigh with intense light surrounding him that blinds all warriors, who then repent their evil ways and promise to lead a moral life if their eyesight is restored. The boy grants them the boon.[10]

- In chapter 4 of the Vishnu Purana, Rcika prepares a meal for two women, one simple, and another with ingredients that if eaten would cause the woman to conceive a son with martial powers. The latter is accidentally eaten by Renuka, and she then gives birth to Parashurama.[10]

- In chapter 2 of the Vayu Purana, he is born after his mother Renuka eats a sacrificial offering made to both Rudra (Shiva) and Vishnu, which gives him dual characteristics of Kshatriya and Brahmin.[18]

Parashurama is described in some versions of the Mahabharata as the angry Brahmin who with his axe, killed a huge number of Kshatriya warriors because they were abusing their power.[19] In other versions, he even kills his own mother because his father asks him to and claims she had committed a sin by having lustful thoughts after seeing a young couple frolicking in water.[20][9] After Parasurama obeys his father's order to kill his mother, his father grants him a boon. Parasurama asks for the reward that his mother be brought back to life, and she is restored to life.[20] Parasurama remains filled with sorrow after the violence, repents and expiates his sin.[9]

He plays important roles in the Mahabharata serving as mentor to Bhishma (chapter 5.178), Drona (chapter 1.121) and Karna (chapter 3.286), teaching weapon arts and helping key warriors in both sides of the war.[21][22][note 3]

In the regional literature of Kerala, he is the founder of the land, the one who brought it out of the sea and settled a Hindu community there.[1] He is also known as Rama Jamadagnya and Rama Bhargava in some Hindu texts.[3] Parashurama retired in the Mahendra Mountains, according to chapter 2.3.47 of the Bhagavata Purana.[24] He is the only Vishnu avatar who never dies, never returns to abstract Vishnu and lives in meditative retirement.[9] Further, he is the only Vishnu avatar that co-exists with other Vishnu avatars Rama and Krishna in some versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata respectively.[9][note 4]

Parashurama Kshetras

There are many interpretation of parashurama kshetras.

The ancient Saptakonkana is a slightly larger region described in the Sahyadrikhanda which refers to it as Parashuramakshetra (Sanskrit for "the area of Parashurama"), Vapi to Tapi is an area of South Gujarat, India. The area blessed by Lord Parshuram and called "Parshuram ni bhoomi".[25]

The region of Konkan is also considered as Parashurama Kshetra.[26][27]

There is a Parshuram Kund, a Hindu pilgrimage centre in Lohit district of Arunachal Pradesh which is dedicated to the sage Parashurama. Thousands of pilgrims visit the place in winter every year, especially on the Makar Sankranti day for a holy dip in the sacred kund which is believed to wash away one's sins.[28][29]

Mahurgad is one of the Shaktipeeth in Maharashtra's Nanded district, where a famous temple of Goddess Renuka exists. This temple at Mahurgad is always full of pilgrims. People also come to visit Lord Parashuram temple on the same Mahurgad.

Iconography

The Hindu literature on iconography such as the Vishnudharmottara Purana and Rupamandana describes him as a man with matted locks, with two hands, one carrying an axe. However, the Agni Purana portrays his iconography with four hands, carrying his axe, bow, arrow and sword. The Bhagavata Purana describes his icon as one with four hands, carrying his axe, bow, arrows and a shield like a warrior.[30] Though a warrior, his representation inside Hindu temples with him in war scenes is rare (the Basohli temple is one such exception). Typically, he is shown with two hands, with an axe in his right hand either seated or standing.[30]

Gallery

_Kerala_India.jpg) A Parasurama temple in Kerala

A Parasurama temple in Kerala- Parasurama in a garden

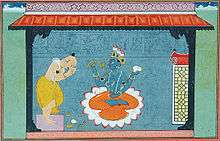

Parashurama returning with the sacred calf with Jamadagni cautioning him to not be controlled by anger

Parashurama returning with the sacred calf with Jamadagni cautioning him to not be controlled by anger

Temples

1. Parshuram Temple in Chiplun, Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, India.

See also

Related Indian topics:

Related International topics:

Notes

- The Mahabharata includes legends about both Arjuna, one is dharmic (moral) and other adharmic (immoral); in some versions, Arjuna Kartavirya has mixed moral-immoral characteristics consistent with the Hindu belief that there is varying degrees of good and evil in every person.[9]

- According to Madeleine Biardeau, Parasurama is a fusion of contradictions, possibly to emphasize the ease with which those with military power tend to abuse it, and the moral issues in circumstances and one's actions, particularly violent ones.[12][13]

- The Sanskrit epic uses multiple names for Parashurama in its verses: Parashurama, Jamadagnya, Rama (his name shortened, but not to be confused with Rama of Ramayana), etc.[23]

- These texts also state that Parasurama lost the essence of Vishnu while he was alive, and Vishnu then appeared as a complete avatar in Rama; later, in Krishna.[9]

References

- Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 500–501. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- Julia Leslie (2014). Myth and Mythmaking: Continuous Evolution in Indian Tradition. Taylor & Francis. pp. 63–66 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-136-77888-9.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parashurama

- ""Parshuram's birthplace near Indore"". Dainik Jagran. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Rajesh Jauhri". ""Janapao all set for Parshurama Jayanti"". Times of India. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ""Janapav to be developed into international pligrim centre"". "One India". Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Khazan Ecosystems of Goa: Building on Indigenous Solutions to Cope with Global Environmental Change (Advances in Asian Human-Environmental Research) (1995). Khazan Ecosystems of Goa: Building on Indigenous Solutions to Cope with Global Environmental Change. Abhinav Publications. p. 29. ISBN 978-9400772014.

- Lynn Thomas (2014). Julia Leslie (ed.). Myth and Mythmaking: Continuous Evolution in Indian Tradition. Routledge. pp. 64–66 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-136-77881-0.

- Thomas E Donaldson (1995). Umakant Premanand Shah (ed.). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah. Abhinav Publications. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

- Thomas E Donaldson (1995). Umakant Premanand Shah (ed.). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah. Abhinav Publications. pp. 161–70. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

- Madeleine BIARDEAU (1976), Études de Mythologie Hindoue (IV): Bhakti et avatāra, Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, École française d’Extrême-Orient, Vol. 63 (1976), pp. 182–191, context: 111–263

- Freda Matchett (2001). Krishna, Lord Or Avatara?. Routledge. pp. 206 with note 53. ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

- Shree Scanda Puran (Sayadri Khandha) -Ed. Dr. Jarson D. Kunha, Marathi version Ed. By Gajanan shastri Gaytonde, published by Shree Katyani Publication, Mumbai

- Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti Part-1, p. 206, B. D. Satoskar, Shubhada Publication

- Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–212. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- Cornelia Dimmitt (2012). Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas. Temple University Press. pp. 82–85. ISBN 978-1-4399-0464-0.

- Thomas E Donaldson (1995). Umakant Premanand Shah (ed.). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah. Abhinav Publications. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

- Ganguly KM (1883). "Drona Parva Section LXX". The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- Daniel E Bassuk (1987). Incarnation in Hinduism and Christianity: The Myth of the God-Man. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-349-08642-9.

- Kisari Mohan Ganguli (1896). "Mahabaratha, Digvijaya yatra of Karna". The Mahabharata. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Lynn Thomas (2014). Julia Leslie (ed.). Myth and Mythmaking: Continuous Evolution in Indian Tradition. Routledge. pp. 66–69 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-136-77881-0.

- Lynn Thomas (2014). Julia Leslie (ed.). Myth and Mythmaking: Continuous Evolution in Indian Tradition. Routledge. pp. 69–71 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-136-77881-0.

- Thomas E Donaldson (1995). Umakant Premanand Shah (ed.). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah. Abhinav Publications. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

- Chandra, Suresh (1998). Encyclopedia of Hindu Gods & Goddesses. Sarup & Sons. p. 376.

- Stanley Wolpert (2006), Encyclopedia of India, Thomson Gale, ISBN 0-684-31350-2, page 80

- Thomas E Donaldson (1995). Umakant Premanand Shah (ed.). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah. Abhinav Publications. pp. 170–174. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

- "Thousands gather at Parshuram Kund for holy dip on Makar Sankranti". The News Mill. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "70,000 devotees take holy dip in Parshuram Kund". Indian Express. 18 January 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Thomas E Donaldson (1995). Umakant Premanand Shah (ed.). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah. Abhinav Publications. pp. 178–180. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

- Thomas E Donaldson (1995). Umakant Premanand Shah (ed.). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah. Abhinav Publications. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

Bibliography

- KM, Ganguly (2016) [1883]. The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa (Drona Parva Section LXX ed.). Sacred Texts.

- Mackenzie, Donald A (1913). Indian Myth and Legend. Sacred Texts.

External links

- 108 Parashurama Kshetras published by Shaivam and Google Maps