Sangam period

The Sangam Age was the period of history of ancient Tamil Nadu and Kerala and parts of Sri Lanka (then known as Tamilakam) spanning from c. 6th century BCE to c. 3rd century CE. It was named after the famous Sangam academies of poets and scholars centered in the city of Madurai.

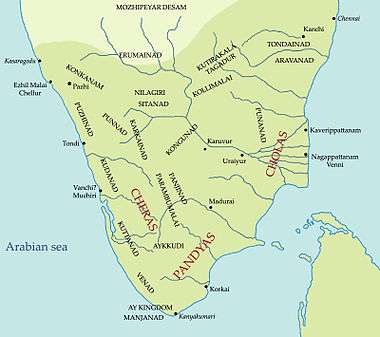

In Old Tamil language, the term Tamilakam (Tamiḻakam தமிழகம், Purananuru 168. 18) referred to the whole of the ancient Tamil-speaking area, corresponding roughly to the area known as southern India today, consisting of the territories of the present-day Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, parts of Andhra Pradesh, parts of Karnataka and northern Sri Lanka[1][2] also known as Eelam.[3][4]

History

According to Tamil legends, there were three Sangam periods, namely Head Sangam, Middle Sangam and Last Sangam period. Historians use the term Sangam period to refer the last of these, with the first two being legendary. So it is also called Last Sangam period (Tamil: கடைச்சங்க பருவம், Kadaissanga paruvam ?),[5] or Third Sangam period (Tamil: மூன்றாம் சங்க பருவம், Mūnṟām sanka paruvam ?). The Sangam literature is thought to have been produced in three Sangam academies of each period. The evidence on the early history of the Tamil kingdoms consists of the epigraphs of the region, the Sangam literature, and archaeological data.

The period between 600 BCE to 300 CE, Tamilakam was ruled by the three Tamil dynasties of Pandya, Chola and Chera, and a few independent chieftains, the Velir.

| Sangam | Time span | No. of Poets | Kingdom[6] | Books[6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 4440 years[6] | 549[6] | Pandiya | No books survived |

| Second | 3700 years[6] | 1700[6] | Pandiya | Tolkāppiyam (author - Tolkāppiyar) |

| Third | 1850 years[6] | Pandiya | covers entire corpus of Sangam Literature |

Literary sources

There is a wealth of sources detailing the history, socio-political environment and cultural practices of ancient Tamilakam, including volumes of literature and epigraphy.[3]

Tamilakam's history is split into three periods; prehistoric, classical (see Sangam period) and medieval. A vast array of literary, epigraphical and inscribed sources from around the world provide insight into the socio-political and cultural occurrences in the Tamil region. The ancient Tamil literature consists of the grammatical work Tolkappiyam, the anthology of ten mid-length books collection Pathupattu, the eight anthologies of poetic work Ettuthogai, the eighteen minor works Patiṉeṇkīḻkaṇakku; and there are The Five Great Epics of Tamil Literature composed in classical Tamil language — Manimegalai, Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi, Silappadikaram, Valayapathi and Kundalakesi as well as five lesser Tamil epics, Ainchirukappiyangal, which are Neelakesi, Naga kumara kaviyam, Udhyana kumara Kaviyam, Yasodhara Kaviyam and Soolamani.

Culture

Religion

The religion of the ancient Tamils closely follow roots of nature worship and some elements of it can also be found in Tamil Shaiva Siddhanta traditions. In the ancient Sangam literature, Sivan was the supreme God, and Murugan was the one celebrated by the masses; both of them were sung as deified Tamil poets ascending the Koodal academy. The Tamil landscape was classified into five categories, thinais, based on the mood, the season and the land. Tolkappiyam, one of the oldest grammatical works in Tamil mentions that each of these thinai had an associated deity such as Kottravai (Mother goddess i.e. Kali) and Sevvael (Murugan) in Kurinji (the hills), Thirumal (Maayon) in Mullai (the forests), Vendhan (Wanji-ko or Seyyon i.e. Indra) in Marutham (the plains i.e. Vayu), and Kadaloan (Varuna) in the Neithal (the coasts and the seas). Other ancient works refer to Maayon (Maal) and Vaali.

The most popular deity was Murugan, who has from a very early date been identified with Karthikeya, the son of Siva. Kannagi, the heroine of the Silappatikaram, was worshiped as Pathini (பத்தினி) by many Tamilians, particularly in Sri Lanka. There were also many temples and devotees of Thirumal, Siva, Ganapathi, and the other common Hindu deities.

Calendar

The ancient Tamil calendar was based on the sidereal year similar to the ancient Hindu solar calendar, except that months were from solar calculations, and originally there was no 60-year cycle as seen in Sanskrit calendar. The year was made up of twelve months and every two months constituted a season. With the popularity of Mazhai vizhavu, traditionally commencement of Tamil year was clubbed on April 14, deviating from the astronomical date of vadavazhi vizhavu.

Festivals

- Pongal (பொங்கல்) the festival of harvest and spring, thanking Lord El (the sun), comes on January 14/15 (Thai 1).

- Peru Vaenil Kadavizha, the festival for wishing quick and easy passage of the mid-summer months, on the day when the Sun or El stands directly above the head at noon (the start of Agni Natchaththiram) at the southern tip of ancient Tamil land. This day comes on April 14/15 (Chithirai 1).

- Mazhai Vizhavu, aka Indhira Vizha, the festival for want of rain, celebrated for one full month starting from the full moon in Ootrai (later name-Cittirai) சித்திரை and completed on the full moon in Puyaazhi (Vaikaasi) (which coincides with Buddhapurnima). It is epitomised in the epic Cilapatikaram in detail.

- Puyaazhi (Vaikaasi) visaagam and Thai poosam, தைப்பூசம் the festivals of Tamil God [Muruga]'s birth and accession to the Thirupparankundram Koodal Academy, coming on the day before the full moons of Puyaazhi and Thai respectively.

- Soornavai Vizha, the slaying of legendary Kadamba Asura king Surabadma, by Lord [Muruga], comes on the sixth day after new moon in Itrai (Kaarthigai). It is sung about in Thirumurugatrupadai and Purananuru anthology.

- Vaadai Vizha or Vadavazhi Vizha, the festival of welcoming the Lord Surya back to home, as He turns northward, celebrated on December 21/22 (Winter Solstice) (the sixth day of Panmizh[Maargazhi]). It is sung about in Akanauru anthology.

- Semmeen Ezhumin Vizhavu (Aathi-Iřai Darisanam) or Aruthra Darishanam, the occasion of Lord Siva coming down from the ThiruCitrambalam திருச்சிற்றம்பலம் and taking a look at the Vaigarai Thiru Aathirai star in the early morning on the day before the full moon in Panmizh. Aathi Irai min means the star of the God (Siva) on the Bull (Nandi).

- Thiruonam or Onam, considered to be the birthday of Mayon, by the people of Pandya kingdom and was celebrated for 10 days. That was mentioned in '[Maduraikanji]' one of the 'Pathupaatu' book, 'Thirupallandu' by Periyazhwar and from the song of Thirugnanasambandhar in Thevaram. On this day, Keralites celebrate Onam as the state's harvest festival. Onam is observed for 10 days, ending in Thiruvonam (or Thirounam).

Arts

Musicians, stage artists, and performers entertained the kings, the nobility, the rich and the general population. Groups of performers included:

- Thudian, players of the thuda, a small percussion instrument

- Paraiyan, who beat maylam (drums) and performed kooththu, a stage drama in dance form, as well as proclaiming the king's announcements

- Muzhavan, who blew into a muzhavu, a wind instrument, with the army indicating the start and end of the day and battlefield victories. They also performed in kooththu alongside other artists.

- Kadamban who beat a large bass-like drum, the kadamparai, and blew a long bamboo, kuzhal, the cerioothuthi (similar to the present naagasuram).

- PaaNan, who sang songs in all pann tunes (tunes that are specific for each landscape) and were masters of the yaazh, a stringed instrument with a wide frequency range.

Together with the poets (pulavar) and the academic scholars (saandror), these people of talent appeared to originate from all walks of life, irrespective of their native profession.

People

The people were divided into five different clans ("kudes") based on their profession. They were:

- Mallars: the farmers

- Malavars: the hill people who gather hill products, and the traders

- Nagars: people in charge of border security, who guarded the city walls and distant fortresses

- Kadambars: people who thrive in forests

- Thiraiyars: the seafarers

- Maravars: the warriors.

All the five kudes constituted a typical settlement, which was called an "uru". Later each clan spread across the land, formed individual settlements of their own and concentrated into towns, cities, and countries. Thus the Mallars settled in Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka, while the Malavars came to live in Kerala, western Tamil Nadu, eastern Andhra Pradesh and southern Sri Lanka. The Nagars inhabited southern and eastern Tamil Nadu, and northern Sri Lanka, while the Kadambars settled in central Tamil Nadu first and later moved to western Karnataka. The Thiraiyars inhabited throughout the coastal regions. Later various subsects were formed based on more specific professions in each of the five landscapes (Kurinji, Mullai, Marutam, Neithal and Palai).

- Poruppas (the soldiers), Verpans (the leaders of the tribe or weapon-ists), Silambans (the masters of martial arts or the arts of fighting), Kuravar (the hunters and the gatherers, the people of foothills) and Kanavars (the people of the mountainous forests) in Kurinji.

- Kurumporai Nadan-kizhaththis (the landlords of the small towns amidst the forests in the valleys), Thonral-manaivi (the ministers and other noble couples), Idaiyars (the milkmaids and their families), Aiyars (the cattle-rearers) in Mullai.

- Mallar or Pallar (the farmers), Maravars (the warriors) Vendans (Chera, Chola, and Pandya kings were called as "Vendans"), Urans (small landlords), Magizhnans (successful small scale farmers), Uzhavars (the farm workers), Kadaiyars (the merchants) in Marutham.[8]

- Saerppans (the seafood vendors and traders), Pulampans (the vegetarians who thrive on coconut and palm products), Parathars or Paravas (people who lived near the seas-the rulers, sea warriors, merchants and the pirates), Nulaiyars (the wealthy people who both do fishing and grow palm farms) and Alavars (the salt cultivators) in Neithal.

- Palai symbolises the dry arid lands and scorching deserts of Tamil country where nothing except for the hardy and war-like perseverant tribes native to those lands can survive. It is also the only land among all five lands of the Sangam landscape that a female God, fierce mother goddess, Kotravai was worshipped which is synonymous with the common belief that all the other lands of Tamil country emerged from these original dry arid lands. The tribes existed in these lands were the ruthless and fearsome Maravars (Noble Warriors, Hunters and Bandits) and Eyinars (Warriors and Bandits). They actively seek out for wars, knowledge, invade far and distant lands and engage in banditry.

- people were known on the basis of their occupation they followed such as artisans, merchants etc.

- warriors occupied a special position in society and memorial stones called "Nadukan" were raised in honour of those who died in fighting and they were worshiped.[9]

See also

- History of Tamil Nadu

- Tolkappiyam

- Purananuru

- Paripaatal

References

Notes

- Wilson, A.Jeyaratnam (2000). Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in 19th and 20th Centuries. "They had earlier felt secure in the concept of the Tamilakam, a vast area of "Tamilness" from the south of Dekhan in India to the north of Sri Lanka...". ISBN 9780774807593. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Pierre-Yves Manguin; A Mani; Geoff Wade (2011). Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross Cultural exchange. originally imported from Kerala to Tamilakam(Southern India) to Illam(Sri Lanka). ISBN 9789814345101.

- Abraham, Shinu (2003). "Chera, Chola, Pandya: using archaeological evidence to identify the Tamil kingdoms of early historic South India". Asian Perspectives. 42 (2): 207–223. doi:10.1353/asi.2003.0031. hdl:10125/17189.

- "Women, Transition, and Change: A Study of the Impact of Conflict and Displacement on Women in Traditional Tamil Society". 1995.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The smile of Murugan on Tamil literature of South India. BRILL. p. 46.

- Daniélou, Alain (11 February 2003). A Brief History of India. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781594777943.

- Rosen, Elizabeth S. (1975). "Prince ILango Adigal, Shilappadikaram (The anklet Bracelet), translated by Alain Damelou. Review". Artibus Asiae. 37 (1/2): 148–150. doi:10.2307/3250226. JSTOR 3250226.

- Mannar Uruvana 'Mallar' Varalaru Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Kanakasabhai, V (1997). The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. ISBN 9788120601505.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sangam period. |

- A. L. Basham, The Wonder that was India, Picador (1995) ISBN 0-330-43909-X

- P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar, History of the Tamils from the earliest times to 600 AD, Madras, 1929; Chennai, Asian Educational Svcs. (2001) ISBN 81-206-0145-9.

- "History of Mallars"