Mahabali

Mahabali (IAST: Mahābalī), also known as Bali or Māveli, is a Mythological daitya King found in Hindu texts. He was the son of Virochana and the grandson of Prahlada. There are many versions of his legend in ancient texts such as the Shatapatha Brahmana, Ramayana, Mahabharata and Puranas.[1][2] [3] His legend is a part of the annual Balipratipada (fourth day of Diwali) festival in the States of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Onam festival in the state of Kerala, India.[1][4]

| Mahabali | |

|---|---|

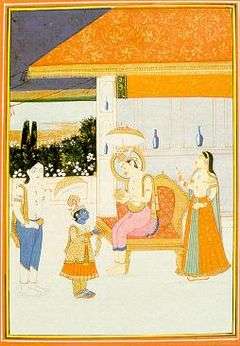

Vamana with Bali Maharaj | |

| In-universe information | |

| Family |

|

| Children | Banasura, Ratanamala, Vajrajwala |

Hindu mythologies

Mahabali is described in early Hindu mythologies as a benevolent and generous king, but violent and surrounded by asura associates who abused power. They particularly persecuted the suras and the Brahmins.[5][6][3] Mahabali also temporarily possessed the amrita (nectar for eternal life) obtained by the asuras by trickery.[7] The amrita allowed his associates to bring him back to life after his death in one of the wars between suras and asuras.[8][7] Mahabali was, thus, immune from death. After many wars, the invincible Bali had won the heaven and earth. The suras (Devas) approach Vishnu to save them. Vishnu refused to join the war or kill his own devotee Mahabali. He used a tactical approach instead and incarnated as the dwarf Brahmin avatar, Vamana. While Mahabali was performing Ashvamedha Vedic sacrifices to celebrate his victories and giving away gifts to everyone, Vamana approached him and asked for "three steps of land".[8][9] Mahabali granted him the gift. Vamana then metamorphosed into Vishnu's giant Trivikrama form, taking all of heaven in one step and earth in second. Mahabali realized that the Vamana was none other than Vishnu and offered his own head for the third step. Some Hindu texts state that Mahabali became the king of Sutala (a world more beautiful than Swarga, where Vishnu himself attended to Mahabali), some state he entered heaven with the touch of Vishnu, while another version states he became chiranjivi (immortal).[8]

According to Hindu mythologies, Vishnu granted Bali a boon whereby he could return to earth every year. The harvest festivals of Balipratipada and Onam are celebrated to mark his yearly homecoming.[1][4][10] Literature and inscriptions in Hindu temples suggest that these festivals, featuring colorful decorations, lighted lamps, gift giving, feasts and community events, have been popular in India for more than a millennium.[1][11]

Jain mythologies

King Bali is also found in the mythologies of Jainism. He is the sixth of nine Prativasudevas (Prati-narayanas, anti-heroes).[12] He is depicted as an evil king who schemed and attempted to rob Purusha's wife.[13] He is defeated and killed by Purusha. In Jain mythology, the antagonists to Bali are the two sons born to King Mahasiva (Mahasiras): Ananda (the sixth Baladeva) and Purusapundarika (the sixth Vasudeva).[13]

Bali is also mentioned in Jain inscriptions, where the patron compares the defeated evil opponents of the current king to Bali. For example, in the Girnar inscriptions of Gujarat dated to about 1231 CE (1288 Vikrama era), minister Vastupala of the Chaulukya dynasty is praised as a great king by Jains, and the inscriptions connect him to Bali because Vastupala gave much charity. Some excerpts from the inscriptions are:

- In olden times Bali was pressed down by the foot of Vishnu, the enemy of the demons, from the earth; now the same is done by the hand of Vastupala,...[14]

- O Vastupala, Bali has sent thee a message that he has been much pleased by hearing from Narada, who visits the three worlds, that though frequently solicited thou dost not extend thy anger to the needy,...[15]

- By the famous minister Vastupala watering the earth with nectarial charities, the pride of Bali and Kalpataru has been greatly lowered...[16]

- Let there be continuous salutation to holy Bali and Karna, whose charity though unseen has been the object of so much fame; consequently the people are worthy of worship, and the great minister Vastupala's charity which the people see with their eyes so great that even the world itself can scarcely contain it.[17]

Mahabali is a common name and found in other contexts. For example, in Jain history, Mahabali is the name of the son of Bahubali, who was given Bahubali's kingdom before Bahubali became a monk.[18]

Cultural sites

In Kerala, Mahabali is remembered as the mythical king who lived there. However, in other parts of India, he is believed to have lived and ruled from other locations. For example, in the north the eponymous Balia (Uttar Pradesh) is believed to be his capital.[5] In Maharashtra, the hill town of Mahabaleshwar is considered as his abode before he was sent to Sutala by Vishnu. In Gujarat, it is Bharuch that is linked to him and this is attested to in the Matsya Purana chapter 114.[5] The town of Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu is also associated with him and considered his capital.[5]

See also

Notes

- PV Kane (1958). History of Dharmasastra, Volume 5 Part 1. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 201–206.

- Nanditha Kirshna (2009). Book of Vishnu. Penguin Books. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-81-8475-865-8.

- Narayan, R.K (1977). The Ramayana: a shortened modern prose version of the Indian epic. Mahabali story. Penguin Classics. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-14-018700-7.

- Constance A Jones (2011). J. Gordon Melton (ed.). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. pp. 634, 900. ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- D Dennis Hudson (2008). The Body of God: An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram. Oxford University Press. pp. 163–174. ISBN 978-0-19-970902-1.

- George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- D Dennis Hudson (2008). The Body of God: An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram. Oxford University Press. pp. 207–219. ISBN 978-0-19-970902-1.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 74.

- A.M. Kurup (1977). "The Sociology of Onam". Indian Anthropologist. 7 (2): 95–110. JSTOR 41919319.

- von Glasenapp 1999, p. 288.

- von Glasenapp 1999, p. 308.

- Burgess 1885, p. 285.

- Burgess 1885, p. 291.

- Burgess 1885, p. 292.

- Burgess 1885, p. 294.

- Vijay K. Jain 2013, p. xi.

References

- Burgess, James (1885), Lists of the Antiquarian Remains in the Bombay Presidency: With an Appendix of Inscriptions from Gujarat, Archaeological Survey of India

- Jain, Vijay K. (2013), Ācārya Nemichandra's Dravyasaṃgraha, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363952,

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1376-6