Lake Tahoe

| Lake Tahoe | |

|---|---|

The south shore in California as seen from Chimney Bay on the Nevada side | |

| Location | The Sierra Nevada of the U.S., along the state line of California and Nevada |

| Coordinates | 39°05.5′N 120°02.5′W / 39.0917°N 120.0417°WCoordinates: 39°05.5′N 120°02.5′W / 39.0917°N 120.0417°W |

| Lake type | Geologic block faulting |

| Primary outflows | Truckee River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 22 mi (35 km) |

| Max. width | 12 mi (19 km) |

| Surface area |

191 sq mi (490 km2):[1] |

| Average depth | 1,000 ft (300 m)[1] |

| Max. depth | 1,645 ft (501 m) |

| Water volume | 36 cu mi (150 km3)[2] |

| Residence time | 650 years |

| Shore length1 | 71 mi (114 km) |

| Surface elevation | 6,225 ft (1,897 m)[1] |

| Frozen | Never |

| Islands | Fannette Island |

| Settlements |

Incline Village, NV South Lake Tahoe, CA Stateline, NV Tahoe City, CA |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Lake Tahoe (/ˈtɑːhoʊ/; Washo: dáʔaw) is a large freshwater lake in the Sierra Nevada of the United States. Lying at 6,225 ft (1,897 m), it straddles the state line between California and Nevada, west of Carson City. Lake Tahoe is the largest alpine lake in North America,[3] and at 122,160,280 acre⋅ft (150,682,490 dam3) trails only the five Great Lakes as the largest by volume in the United States. Its depth is 1,645 ft (501 m), making it the second deepest in the United States after Crater Lake in Oregon (1,945 ft (593 m)).[1]

The lake was formed about 2 million years ago as part of the Lake Tahoe Basin, with the modern extent being shaped during the ice ages. It is known for the clarity of its water and the panorama of surrounding mountains on all sides.[4] The area surrounding the lake is also referred to as Lake Tahoe, or simply Tahoe. More than 75% of the lake's watershed is national forest land, comprising the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit of the United States Forest Service.

Lake Tahoe is a major tourist attraction in both Nevada and California. It is home to winter sports, summer outdoor recreation, and scenery enjoyed throughout the year. Snow and ski resorts are a significant part of the area's economy and reputation.[5][6] The Nevada side also offers large casinos, with highways providing year-round access to the entire area.

Geography

Lake Tahoe is the second deepest lake in the U.S., with a maximum depth of 1,645 feet (501 m),[1][7] trailing Oregon's Crater Lake at 1,949 ft (594 m).[7] Tahoe is the 16th[8] deepest lake in the world, and the fifth deepest in average depth. It is about 22 mi (35 km) long and 12 mi (19 km) wide and has 72 mi (116 km) of shoreline and a surface area of 191 square miles (490 km2). The lake is so large that its surface is noticeably convex due to the curvature of the earth. At lake level the opposing shorelines are below the horizon at its widest parts; by nearly 100 feet (30 m) at its maximum width, and by some 320 feet (98 m) along its length.[9][10] Visibility may vary somewhat with atmospheric refraction;[11] when the air temperature is much greater than the lake temperature, looming may occur where the lake surface or opposing shoreline is lifted above the horizon. Fata Morgana may be responsible for Tahoe Tessie sightings.

Approximately two-thirds of the shoreline is in California.[12] The south shore is dominated by the lake's largest city, South Lake Tahoe, California, which adjoins the town of Stateline, Nevada, while Tahoe City, California, is located on the lake's northwest shore. Although highways run within sight of the lake shore for much of Tahoe's perimeter, many important parts of the shoreline lie within state parks or are protected by the United States Forest Service. The Lake Tahoe Watershed (USGS Huc 18100200) of 505 sq mi (1,310 km2) includes the land area that drains to the lake and the Lake Tahoe drainage divide traverses the same general area as the Tahoe Rim Trail.

Lake Tahoe is fed by 63 tributaries. These drain an area about the same size as the lake and produce half its water, with the balance entering as rain or snow falling directly on it.

The Truckee River is the lake's only outlet,[3] flowing northeast through Reno, Nevada, into Pyramid Lake which has no outlet. It accounts for one third of the water that leaves the lake, the rest evaporating from the lake's vast surface. The flow of the Truckee River and the height of the lake are controlled by the Lake Tahoe Dam at the outlet. The natural rim is at 6,223 ft (1,897 m) above sea level, with a spillway at the dam controlling overflow. The maximum legal limit, to which the lake can be allowed to rise in order to store water, is at 6,229.1 ft (1,898.6 m).[13] Around New Year 1996/1997 a Pineapple Express atmospheric river melted snow and caused the lake and river to overflow, inundating Reno and surrounding areas.[14]

Natural history

Geology

The Lake Tahoe Basin was formed by vertical motion (normal) faulting. Uplifted blocks created the Carson Range on the east and the main Sierra Nevada crest on the west. Down-dropping and block tilting (half-grabens) created the Lake Tahoe Basin in between.[1] This kind of faulting is characteristic of the geology of the adjoining Great Basin to the east.

Lake Tahoe is the youngest of several extensional basins of the Walker Lane deformation zone that accommodates nearly 12 mm/yr of dextral shear between the Sierra Nevada-Great Valley Block and North America.[15][16]

Three principal faults form the Lake Tahoe basin: the West Tahoe Fault, aligned between Meyers and Tahoe City, and which is the local segment of the Sierra Nevada Fault, extending on shore north and south of these localities;[17] the Stateline/North Tahoe Fault, starting in the middle of the lake and creating the relief that forms Stateline, NV; and the Incline Village Fault, which runs parallel to the Stateline/North Tahoe Fault offshore and into Incline Village.[18] The West Tahoe Fault appears to be the most active and potentially hazardous fault in the basin. A study in Fallen Leaf Lake, just south of Lake Tahoe, used seafloor mapping techniques to image evidence for paleoearthquakes on the West Tahoe and revealed the last earthquake occurred between 4,100 and 4,500 years ago.[19] Subsequent studies revealed submarine landslides in Fallen Leaf Lake and Lake Tahoe that are thought to have been triggered by earthquakes on the West Tahoe fault and the timing of these events suggests a recurrence interval of 3,000–4,000 years.[20]

Some of the highest peaks of the Lake Tahoe Basin that formed during the process of Lake Tahoe creation are Freel Peak at 10,891 feet (3,320 m), Monument Peak at 10,067 feet (3,068 m), Pyramid Peak at 9,984 feet (3,043 m) (in the Desolation Wilderness), and Mount Tallac at 9,735 feet (2,967 m).[1] The north shore boasts three peaks at 10,000+ feet: Mount Rose at 10,785 feet (3,287 m), and Houghton and Relay peaks. Mt. Rose is a very popular hiking and backcountry skiing destination.

Eruptions from the extinct volcano Mount Pluto formed a dam on the north side. Melting snow filled the southern and lowest part of the basin to form the ancestral Lake Tahoe. Rain and runoff added additional water.[21]

The Sierra Nevada adjacent to Lake Tahoe were carved by scouring glaciers during the Ice Ages, which began a million or more years ago, and retreated ~15,000 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene. The glaciers carved canyons that are today iconic landmarks such as Emerald Bay, Cascade Lake, and Fallen Leaf Lake, among others. Lake Tahoe itself never held glaciers, but instead water is retained by damming Miocene volcanic deposits.

Soils of the basin come primarily from andesitic volcanic rocks and granodiorite, with minor areas of metamorphic rock. Some of the valley bottoms and lower hill slopes are mantled with glacial moraines, or glacial outwash material derived from the parent rock. Sandy soils, rock outcrops and rubble and stony colluvium account for over 70% of the land area in the basin. The basin soils (in the < 2 mm fraction) are generally 65–85% sand (0.05–2.0 mm).

Given the great depth of Lake Tahoe, and the locations of the normal faults within the deepest portions of the lake, modeling suggests that earthquakes on these faults can trigger tsunamis. Wave heights of these tsunamis are predicted to be on the order of 10 to 33 ft (3 to 10 m) in height, capable of traversing the lake in just a few minutes.[22] A massive collapse of the western edge of the basin that formed McKinney Bay around 50,000 years ago is thought to have generated a tsunami/seiche wave with a height approaching 330 ft (100 m).[23]

Climate

Lake Tahoe has a dry-summer continental climate (Dsb in the Köppen climate classification), featuring warm, dry summers and chilly winters with regular snowfall. Mean annual precipitation ranges from over 55 inches (1440 mm) for watersheds on the west side of the basin to about 26 inches (660 mm) near the lake on the east side of the basin. Most of the precipitation falls as snow between November and April, although rainstorms combined with rapid snowmelt account for the largest floods. There is a pronounced annual runoff of snowmelt in late spring and early summer, the timing of which varies from year to year. In some years, summertime monsoon storms from the Great Basin bring intense rainfall, especially to high elevations on the northeast side of the basin.

August is normally the warmest month at the Lake Tahoe Airport (elevation 6,254 ft, 1,906 m) with an average maximum of 78.7 °F (25.9 °C) and an average minimum of 39.8 °F (4.3 °C). January is the coolest month with an average maximum of 41.0 °F (5.0 °C) and an average minimum of 15.1 °F (−9.4 °C). The all-time maximum of 99 °F (37.2 °C) was recorded on July 22, 1988. The all-time minimum of −16 °F (−26.7 °C) was recorded on December 9, 1972. Temperatures exceed 90 °F (32.2 °C) on an average of 2.0 days annually. Minimum temperatures of 32 °F (0 °C) or lower occur on an average of 231.8 days annually, and minimum temperatures of 0 °F (−17.8 °C) or lower occur on an average of 7.6 days annually. Freezing temperatures have occurred in every month of the year.[24][25]

| Climate data for Tahoe City, California (Elevation 6,230 ft, 1,899 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 59 (15) |

60 (16) |

67 (19) |

74 (23) |

89 (32) |

90 (32) |

99 (37) |

94 (34) |

87 (31) |

80 (27) |

70 (21) |

60 (16) |

99 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 38.6 (3.7) |

40.3 (4.6) |

44.0 (6.7) |

50.4 (10.2) |

59.6 (15.3) |

68.7 (20.4) |

77.9 (25.5) |

77.2 (25.1) |

69.8 (21) |

58.8 (14.9) |

46.9 (8.3) |

40.3 (4.6) |

56.0 (13.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19.1 (−7.2) |

19.9 (−6.7) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

32.8 (0.4) |

38.6 (3.7) |

44.4 (6.9) |

43.7 (6.5) |

39.0 (3.9) |

32.3 (0.2) |

25.8 (−3.4) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−15 (−26) |

−6 (−21) |

5 (−15) |

9 (−13) |

24 (−4) |

22 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

21 (−6) |

9 (−13) |

1 (−17) |

−16 (−27) |

−16 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.97 (151.6) |

5.29 (134.4) |

4.12 (104.6) |

2.14 (54.4) |

1.20 (30.5) |

0.65 (16.5) |

0.26 (6.6) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.59 (15) |

1.82 (46.2) |

3.57 (90.7) |

5.55 (141) |

31.47 (799.3) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 45.9 (116.6) |

36.5 (92.7) |

35.2 (89.4) |

15.9 (40.4) |

3.7 (9.4) |

0.2 (0.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.8) |

2.4 (6.1) |

15.5 (39.4) |

35.2 (89.4) |

190.7 (484.4) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[26] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

Vegetation in the basin is dominated by a mixed conifer forest of Jeffrey pine (Pinus jeffreyi), lodgepole pine (P. contorta), white fir (Abies concolor), and red fir (A. magnifica).[29] The basin also contains significant areas of wet meadows and riparian areas, dry meadows, brush fields (with Arctostaphylos and Ceanothus) and rock outcrop areas, especially at higher elevations. Ceanothus is capable of fixing nitrogen, but mountain alder (Alnus tenuifolia), which grows along many of the basin’s streams, springs and seeps, fixes far greater quantities, and contributes measurably to nitrate-N concentrations in some small streams. The beaches of Lake Tahoe are the only known habitat for the rare Lake Tahoe yellowcress (Rorippa subumbellata), a plant which grows in the wet sand between low- and high-water marks.[30]

Each autumn, from late September through mid-October, mature kokanee salmon (Oncorhyncus nerka) transform from silver-blue color to a fiery vermilion, and run up Taylor Creek, near South Lake Tahoe. As spawning season approaches the fish acquire a humpback and protuberant jaw. After spawning they die and their carcasses provide a feast for gatherings of mink (Neovison vison), bears (Ursus americanus), and bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). The non-native salmon were transplanted from the North Pacific to Lake Tahoe in 1944.[31]

North American beaver (Castor canadensis) were re-introduced to the Tahoe Basin by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the U.S. Forest Service between 1934 and 1949. Descended from no more than nine individuals, 1987 beaver populations on the upper and lower Truckee River had reached a density of 0.72 colonies (3.5 beavers) per kilometer.[32] At the present time beaver have been seen in Tahoe Keys, Taylor Creek, Meeks Creek at Meeks Bay on the western shore, and Kings Beach on the north shore, so the descendants of the original nine beavers have apparently migrated around most of Lake Tahoe.[33][34] Recently novel physical evidence has demonstrated that beaver were native to the Sierra until at least the mid-nineteenth century, via radiocarbon dating of buried beaver dam wood uncovered by deep channel incision in the Feather River watershed.[35] That report was supported by a summary of indirect evidence of beaver including reliable observer accounts of beaver in multiple watersheds from the northern to the southern Sierra Nevada, including its eastern slope.[36] A specific documented record of beaver living historically in Lake Tahoe's North Canyon Creek watershed above Glenbrook includes a description of Spooner Meadow rancher Charles Fulstone hiring a caretaker to control the beaver population in the early 20th century.[37] A recent study of Taylor Creek showed that beaver dam removal decreased wetland habitat, increased stream flow, and increased total phosphorus pollutants entering Lake Tahoe – all factors which negatively impact the clarity of the lake's water.[38] In addition, beaver dams located in Ward Creek, located on the west shore of Lake Tahoe, were also shown to decrease nutrients and sediments traveling downstream.[38]

The lake's cold temperatures and extreme depth can slow the decomposition rate of organic matter. For example, a diver was found at a depth of 300 feet (90 m) 17 years after being lost, with his body preserved nearly perfectly.[39]

Human history

Native people

The area around Lake Tahoe was previously inhabited by the Washoe tribe of Native Americans. Lake Tahoe was the center and heart of Washoe Indian territory, including the upper valleys of the Walker, Carson and Truckee Rivers. The English name for Lake Tahoe derives from the Washo word "dá’aw," meaning "The Lake."[40]

Exploration and naming

Lt. John C. Frémont was the first person of European descent to see Lake Tahoe, during Fremont's second exploratory expedition on February 14, 1844.[41] John Calhoun Johnson, Sierra explorer and founder of "Johnson's Cutoff" (now U.S. Route 50) named Fallen Leaf Lake after his Indian guide. Johnson's first job in the west was in the government service, carrying the mail on snowshoes from Placerville to Nevada City, during which time he named the lake "Lake Bigler" in honor of California’s third governor John Bigler.

In 1853 William Eddy, the surveyor general of California, identified the lake as Lake Bigler. During the Civil War, Union advocates objected to the name, because Bigler was an ardent secessionist. Due to this, the U.S. Department of the Interior introduced the name Tahoe in 1862. Both names were in use: the legislature passed legislation declaring the official name to be Lake Bigler in 1870, while to most surveys and the general public it was known as Lake Tahoe.[42] The lake didn't receive its official and final designation as Lake Tahoe until 1945.

Mining era

Upon discovery of gold in the South Fork of the American River in 1848, thousands of gold seekers going west passed near the basin on their way to the gold fields. European civilization first made its mark in the Lake Tahoe basin with the 1858 discovery of the Comstock Lode, a silver deposit just 15 miles (24 km) to the east in Virginia City, Nevada. From 1858 until about 1890, logging in the basin supplied large timbers to shore up the underground workings of the Comstock mines. The logging was so extensive that loggers cut down almost all of the native forest.[43]

Lake Tahoe became a transportation hub for the surrounding area as mining and logging commenced prior to development of railroads. The first mail delivery was via a sailboat which took a week to visit each of the lakeside communities.[44] The first steamboat on Lake Tahoe was the 42-foot (13 m) paddle wheel tugboat Governor Blasdel towing log rafts to a sawmill on the south side of Glenbrook Bay from 1863 until her boiler exploded in 1877. The 40-foot (12 m) Truckee and 55-foot (17 m) propeller-driven Emerald were also towing log rafts in 1870.[45] J.A. Todman brought steam-powered passenger service to Lake Tahoe in 1872 with the 100-foot (30 m) 125-passenger side-wheel steamer Governor Stanford which reduced the mail delivery trip around Lake Tahoe to eight hours.[46] Todman expanded service with steamboats Mamie, Niagara, and Tod Goodwin. Lawrence & Comstock provided competition with their steel-hulled steamboat Tallac in 1890 and later purchased Todman's steamboats Mamie and Tod Goodwin. The Carson and Tahoe Lumber and Fluming Company purchased the 83-foot (25 m) Niagara and built the iron-hulled steamboats Meteor in 1876 and Emerald (II) in 1887. The 75-foot (23 m) Meteor was the fastest boat on Lake Tahoe with a speed of 22 miles (35 km) per hour. Lake Tahoe Railway and Transportation Company dominated the passenger and mail route after launch of their 200-passenger steamboat Tahoe on 24 June 1896. The 154-ton Tahoe was 170 feet (52 m) long with a slender 18-foot (5.5 m) beam so her 1,200 horsepower (890 kW) engines could push her over the lake at 18.5 knots. Lake Tahoe Railway and Transportation Company purchased Tallac and rebuilt her as Nevada with length increased by 20 feet (6.1 m) to serve as a backup steamboat when Tahoe required maintenance.[44]

Tod Goodwin burned at Tallac, and most of the other steamboats were retired as the sawmills ran out of trees and people began traveling by automobile.[44] Niagara was scrapped at Tahoe City in 1900.[46] Governor Stanford was beached at Glenbrook where its boiler was used until 1942 heating cottages at Glenbrook Inn and Ranch. Steamboats continued to carry a mail clerk around Lake Tahoe until 1934, when the mail contract was given to the 42-foot (13 m) motorboat Marian B powered by two Chevrolet engines. Mail delivery moved ashore after Marian B was lost on 17 May 1941 with her owner and the mail clerk attempting mail delivery during a storm.[44] The 60-foot (18 m) Emerald (II) left Lake Tahoe in 1935 to become a fishing boat in San Diego.[45] Historic Tahoe, Nevada, and Meteor were purchased with hope they might be preserved; but were scuttled in deep water after deterioration made preservation impractical. The latter two lie in Glenbrook Bay, but Tahoe sank in deeper water.[44]

Development

Even in the mining era, the potential of the basin as a tourist destination was recognized. Tahoe City was founded in 1864 as a resort community for Virginia City.[43]

Public appreciation of the Tahoe basin grew, and during the 1912, 1913 and 1918 congressional sessions, congressmen tried unsuccessfully to designate the basin as a national park.[43]

While Lake Tahoe is a natural lake, it is also used for water storage by the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District (TCID). The lake level is controlled by Lake Tahoe Dam built in 1913 at the lake's only outlet, the Truckee River, at Tahoe City. The 18-foot (5.5 m) high dam can increase the lake's capacity by 744,600 acre⋅ft (918,500,000 m3).[47]

During the first half of the 20th century, development around the lake consisted of a few vacation homes. The post-World War II population and building boom, followed by construction of gambling casinos in the Nevada part of the basin during the mid-1950s, and completion of the interstate highway links for the 1960 Winter Olympics held at Squaw Valley, resulted in a dramatic increase in development within the basin. From 1960 to 1980, the permanent residential population increased from about 10,000 to greater than 50,000, and the summer population grew from about 10,000 to about 90,000.[43] Since the 1980s, development has slowed due to controls on land use.

Government and politics

Interstate boundary dispute

Lake Tahoe is divided by the prominent interstate boundary between California and Nevada, where the two states' edges make their iconic directional turn near the middle of the lake. This boundary has been disputed since the mid-nineteenth century.[48]

As part of the compromise of 1850, California was speedily admitted to the Union. In doing so, congress approved the California Constitution which defined the state's boundary in reference to geographical coordinates. This includes the section of the 120th meridian that is between the 42nd parallel at the Oregon border to the 39th parallel amid Lake Tahoe, and an oblique line continuing from that point southward to where the Colorado River crosses the 35th parallel.[49] Fourteen years later, congress approved the Nevada Constitution when it was admitted as a state in 1864, which defined its western border at the forty third degree of Longitude West from Washington D.C. and its southwestern border along the oblique section of the boundary line of California. While 43 degrees of longitude west from the Washington Meridian does not really coincide with the 120 degrees longitude west of Greenwich, the 1864 Congress was of the belief that the two lines were identical; the former was abandoned nationally in 1884. The centuries long dispute that erupted began with boundary discrepancies across many surveys within which were valuable mineral deposits; Nevada also had a wish that California would assent to cede its land east of the pacific crest as had been preauthorized by congress in 1850.[48] The first consequential attempt to mark the California-Nevada boundary was the 1863 J.F. Houghton and Butler Ives line. A 1867-1868 survey of the California-Oregon border by Daniel G. Major for the General Land Office found the 120th meridian more than two miles west of the prior line, so it was followed by the 1872 survey by Allexey W. Von Schmidt. Against initial instructions, Von Schmidt began his survey with the 1872 California-Nevada State Boundary Marker[50] which was six-tenths of a mile east of the Houghton-Ives line. When he discovered the Colorado River had shifted at the 35th parallel, he simply changed the endpoint resulting in a survey that was neither straight nor accurate. Substantial doubts lead congress in 1892 to fund the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey to remark the oblique line.[51][52] This new survey found the Von Schmidt line to be 1,600 to 1,800 feet too far west, but both surveys were then used by both states.[53] Unsurprisingly, the combination of the 1893 C.G.S. survey's oblique line and Schmidt's well marked north-south line do not intersect precisely at the 39th parallel as mandated by the California Constitution. Congress does not have the constitutional power to unilaterally move state boundaries.

The wealth in natural resources between the Sierra Crest and the eastern-most sections of survey lines created a powerful source for conflict. Major mining sites in the Tahoe area were in disputed territory. In a striking display of opportunism which ostensibly occurred because the boundary was still "officially" unsurveyed, settlers arrogated parts of California up to the irregular Sierra Crest tens of miles east of the boundary—defined over six years prior—in an attempt to create Nataqua Territory. An armed skirmish known as the Sagebrush War included gunshots exchanged between militia.[54] Even after six surveys, conflict remained over which of them, if any, were legally binding in marking the boundary;[53] this was partially heard by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1980, where the doctrine of acquiescence was invoked.[49]

A boundary defined in terms of geographical coordinates is theoretically precise, but poses pragmatic challenges to implement. Where a particular coordinate actually lays on the surface of the earth is dependent on the figure of the Earth. In the mid 1800s the Bessel ellipsoid of 1841 or the Clarke ellipsoid of 1866 were widely used; the Hayford ellipsoid of 1910 may later have been used by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey. The standard ellipsoid for western states in 1849—which is generally congruent with that year's version of the Astronomical Almanac–is implicit in California's constitutional boundary definition; incessant invention of new datums by new and potentially interested parties do not re-render the old boundary definition. Holding assumptions of the earth back-in-time, modern satellite assisted survey techniques can determine location and transform them onto old ellipsoids to within a centimeter. Celestial navigation[55][56] techniques by contrast, are accurate up to two-fifths of a mile; uncertainty in the latter was known, but precision then was unobtainable.

The legacy of this dispute continues.[53] There is an official federal[51] obelisk-shaped monument marking the oblique California border, which is now surrounded by Edgewood Tahoe golf resort that is claimed and taxed by Nevada.[51][52][57] Disturbing survey monuments is illegal.[58][59][60][61] A federal survey monument was illegally removed to the Lake Tahoe Historical Society circa 2018.[56][58] The Von Schmidt line crosses US 50 on the west edge of present-day Applebee's, and the east edge of the Ashley Marcus Gallery in Tahoe Crescent V Shopping Center.[57][62] The Nevada community of Stateline has been moved east.[63]

Google Maps shows the California border grazing through Harrah's Casino. Of the three interstate streets on the south shore, the border is only tepidly labeled on U.S. Route 50 in small font. Created from land within the dispute zone, Van Sickle Bi-State Park opened in 2011, but it is not a California State Park.

Unbeknownst to the negotiators, this compromise split Lake Tahoe: two-thirds for California, one-third for Nevada.[64] In California, Lake Tahoe is divided between Placer County and El Dorado County. In Nevada, Lake Tahoe is divided among Washoe County, Douglas County and Carson City (an independent city).

Beach ownership

As Lake Tahoe is a U.S. Navigable Waterway,[65][66] under federal jurisdiction,[67][68] the public is allowed to occupy any watercraft as close to any shore as the craft is navigable.[66] Public capacity to navigate across any land formerly inundated by the waterway is not extinguished by the lowering of the lake level; this federal easement is maintained under United States law.[69] On the California side, the shorezone is additionally maintained in a public trust—analogous to an easement.[70] As public land, the shorezone on this side may be used for nearly any purpose,[70] rather than just travel. Neither state has the authority to rescind navigability along the shoreline below the highmark of the waterbody, because it has been granted under federal law through the Enumerated powers of the United States. The entire waterbody is navigable; it is common for the majority of users to be operating negligible draft one-person craft such as kayaks and standup paddleboards.[66]

Like the interstate boundary itself, the high watermark has been disputed as well.[70] The theoretical maximum elevation of the lake is 6,229.1 feet, using the Lake Tahoe datum. The yearly maximum is commonly 0.35 feet (4.2 in) lower;[70] this difference is less than the wave height on a calm day. The state of Nevada has not agreed[71][72] to either a highwater level or datum with California and the US,[73] nor has this waterline been surveyed and marked in either state—making this interstate waterway boundary line somewhat arbitrary and disputed. To be convicted of trespassing, one must be beyond reasonable doubt above the highwater mark, which itself is an arbitrary fact to be found.[74] The water held in the lake is federally controlled by the US Bureau of Reclamation,[75] and immersion of the shoreline itself would be a common law trespass against east lakefront property owners if it were not for the land—below the theoretical maximum elevation of the lake—being in a perpetual federal easement.[76][69][72] Civic leaders for the Nevada shore have been pushing a frivolous[69] states rights theory of property law—which intermittently nullifies federal easements whenever the lake level recedes—which has never been tested in federal court.[71] The sheriffs in Nevada are elected officials; false arrest can lead to an officials imprisonment and cost their electorate hundreds of thousands of dollars.[77][78][79] Tahoe Regional Planning Agency does not have the authority to override existing federal law even if it was also created by congress. Recent attempts by Lakefront Homeowners to use piers as "easement fences" to obstruct beach travel are encroaching centuries of established easement and admiralty law.[70] Building new piers on the California side additionally infringes on the public trust, which among many things, is purposed to preserve the land in its natural state.[70]

Growth

As the population grew and development expanded in the 1960s, the question of protecting the lake became more imperative. In 1969, the U.S. Congress and the California and Nevada State Legislatures created a unique compact to share resources and responsibilities. The Compact established the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA), a bi-state agency charged with environmental protection of the Basin through land-use regulation and planning.[80] In 1980, the U.S. Congress amended the Compact with public law 96-551. The law designated a new agency, the Tahoe Transportation District (TTD), to facilitate and implement Basin and regional transportation improvements/additions for the protection, restoration and use of the lake. Schisms between both agencies and local residents have led to the formation of grass-roots organizations that hold to even stricter environmentalism.[81]

Historical locations

Lake Tahoe is also the location of several 19th and 20th century palatial homes of historical significance. The Thunderbird Lodge built by George Whittel Jr once included nearly 27 miles (43 km) of the Nevada shoreline. Vikingsholm was the original settlement on Emerald Bay and included an island teahouse and a 38-room home. The Ehrman Mansion is a summer home built by a former Wells Fargo president in Sugar Pine Point and is now a state park. The Pony Express had a route that went from Genoa Station over Daggett Pass to Friday's Station and Yanks Station; it succeeded the route through Woodford's Station and Fountain Place Station both on the way to Strawberry Station.[82]

Environmental issues

Water quality

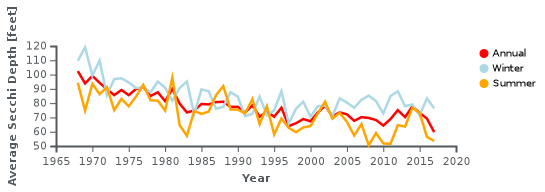

Despite land-use planning and export of treated sewage effluent from the basin, the lake is becoming increasingly eutrophic (having an excessive richness of nutrients), with primary productivity increasing by more than 5% annually, and clarity decreasing at an average rate of 0.25 metres (0.82 ft) per year.[84] Until the early 1980s, nutrient-limitation studies showed that primary productivity in the lake was nitrogen-limited. Now, after a half-century of accelerated nitrogen input (much of it from direct atmospheric deposition), the lake is phosphorus-limited. Theodore Swift et al.,[85] concluded that "suspended inorganic sediments and phytoplanktonic algae both contribute significantly to the reduction in clarity, and that suspended particulate matter, rather than dissolved organic matter, are the dominant causes of clarity loss." The largest source of fine sediment particles to Lake Tahoe is urban stormwater runoff, comprising 72 percent of the total fine sediment particle load.[86] Recent research has shown that the urban uplands also provide the largest opportunity to reduce fine sediment particle and phosphorus contributions to the lake. Historic clarity of approximately 30 metres (98 ft) can be achieved with total reduction of approximately 75 percent from urban sources.[87]

Historically, the clarity of Lake Tahoe continued to decrease through 2010, when the average Secchi depth, 64.4 feet (19.6 m), was the second lowest ever recorded (the lowest was 64.1 feet (19.5 m) in 1997). This represented a decrease of 3.7 feet (1.1 m) from the previous year.[88] However, the lake's clarity increased from 2011 to 2014, improving by nearly 20 percent.[89][90]

A water quality study by the Lahontan Water Quality Control Board and the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection[91] determined the largest source of fine sediment particles: 71 percent is developed area (urban) erosion and run-off, much of it associated with transportation infrastructure and services.[92]

Lake Tahoe is a tributary watershed drainage element within the Truckee River Basin, and its sole outlet is the Truckee River, which continues on to discharge to Pyramid Lake. Because of the sensitivity of Truckee River water quality (involving two protected species, the cui-ui[93] sucker fish and the Lahontan cutthroat trout), this drainage basin has been studied extensively. The primary investigations were stimulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, who funded the development of the DSSAM model to analyze water quality below Lake Tahoe.

Lake Tahoe never freezes.[94] Since 1970, it has mixed to a depth of at least 1,300 ft (400 m) a total of 6 or 7 times. Dissolved oxygen is relatively high from top to bottom. Analysis of the temperature records in Lake Tahoe has shown that the lake warmed (between 1969 and 2002) at an average rate of 0.015 °C per year. The warming is caused primarily by increasing air temperatures, and secondarily by increasing downward long-wave radiation. The warming trend is reducing the frequency of deep mixing in the lake, and may have important effects on water clarity and nutrient cycling.

Ecosystem changes

Since the 1960s, the Lake's food web and zooplankton populations have undergone major changes. In 1963–65, opossum shrimp (Mysis diluviana) were introduced to enhance the food supply for the introduced Kokanee salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). The shrimp began feeding on the lake's cladocerans (Daphnia and Bosmina), and their populations virtually disappeared by 1971.[95] The shrimp provide a food resource for salmon and trout, but also compete with juvenile fish for zooplankton. Since the 1970s, the cladoceran populations have somewhat recovered, but not to former levels. Since 2006, goldfish have been observed in the lake, where they have grown to "giant size", behaving like an invasive species. They may have descended from former pets which owners dumped or escaped, when used as fishing bait.[96]

In June 2007, the Angora Fire burned approximately 3,100 acres (1,300 ha) throughout the South Lake Tahoe area. While the impact of ash on the lake's ecosystem is predicted to be minimal, the impact of potential future erosion is not yet known.[97]

Environmental protection

Until recently, construction on the banks of the Lake had been largely under the control of real estate developers. Construction activities have resulted in a clouding of the lake's blue waters. Currently, the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency is regulating construction along the shoreline[98] (and has won two Federal Supreme Court battles over recent decisions).[99] These regulations are unpopular with many residents, especially those in the Tahoe Lakefront Homeowners Association.[100]

The League to Save Lake Tahoe (Keep Tahoe Blue) has been an environmental watchdog in the Lake Tahoe Basin for 50 years.[101] Founded when a proposal to build a four-lane highway around the lake—with a bridge over the entrance to Emerald Bay—was proposed in 1957, the League has opposed many development projects in the area, which it alleges were environmentally harmful. The League embraces responsible and diversified use of the Lake's resources while protecting and restoring its natural attributes.[101]

Since 1980, the Lake Tahoe Interagency Monitoring Program (LTIMP) has been measuring stream discharge and concentrations of nutrients and sediment in up to 10 tributary streams in the Lake Tahoe Basin, California-Nevada. The objectives of the LTIMP are to acquire and disseminate the water quality information necessary to support science-based environmental planning and decision making in the basin. The LTIMP is a cooperative program with support from 12 federal and state agencies with interests in the Tahoe Basin. This data set, together with more recently acquired data on urban runoff water quality, is being used by the Lahontan Regional Water Quality Control Board to develop a program (mandated by the Clean Water Act) to limit the flux of nutrients and fine sediment to the Lake.

UC Davis remains a primary steward of the lake. The UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center is dedicated to research, education and public outreach, and to providing objective scientific information for restoration and sustainable use of the Lake Tahoe Basin.[102] Each year, it produces a well-publicized "State of the Lake" report, assessing changes such as lake clarity, nutrients and particles, or meteorology around the lake.

Tourist activities

Much of the area surrounding Lake Tahoe is devoted to the tourism industry and there are many restaurants, ski slopes, golf courses and casinos catering to visitors.

Winter sports

During ski season, thousands of people from all over Nevada and California, including Reno, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and Sacramento, flock to the slopes for downhill skiing. Lake Tahoe, in addition to its panoramic beauty, is well known for its blizzards.[5]

Some of the major ski areas in Tahoe include:

- Heavenly Mountain Resort: the largest ski area in California and Nevada, located near Stateline

- Squaw Valley: the second largest ski area, known for its hosting of the 1960 Winter Olympics, located near Tahoe City

- Alpine Meadows: a medium-sized ski area on the north shore only a few miles from Squaw Valley

- Diamond Peak: a small ski area located in Incline Village, Nevada

- Northstar California: a popular north shore ski area

- Kirkwood Mountain Resort: a ski area which gets more snow than any other ski area in the Tahoe region

- Sierra-at-Tahoe: a medium-sized south shore ski area

- Boreal Mountain Resort: a small ski area on Donner Pass

- Sugar Bowl Ski Resort: a medium-sized ski area in Donner Pass

- Donner Ski Ranch: a very small ski area on Donner Pass

- Homewood Mountain Resort: a medium-sized ski area on the west shore

- Mount Rose Ski Resort: a medium-sized ski area north-east of the Lake, on Slide Mountain

The majority of the ski resorts in the Lake Tahoe region are on the northern end of the lake, near Truckee, California and Reno, Nevada. Kirkwood, Sierra-at-Tahoe and Heavenly are located on the southern side of the lake, 55–75 miles (90–120 km) from Reno. Scattered throughout Tahoe are public and private sled parks. Some, such as Granlibakken are equipped with rope tows to help sledders get up the hill.

Many ski areas around Tahoe also have snow tubing, such as Squaw Valley. Throughout Tahoe, cross-country skiing, snowmobile riding and snowshoeing are also popular.

Water sports

During late Spring to early Fall, the lake is popular for water sports and beach activities. The two cities most identified with the Lake Tahoe tourist area are South Lake Tahoe, California and the smaller Stateline; smaller centers on the northern shoreline include Tahoe City and Kings Beach.

Other popular activities include parasailing, jet ski rentals and eco-friendly paddle sport rentals. There are rental locations located around Lake Tahoe. Kayaking and stand up paddle boards have also become very popular.

Boating is a primary activity in Tahoe in the summer. The lake is home to one of the most prestigious wooden boat shows in the country, the Lake Tahoe Concours d'Elegance, held every August. There are lake front restaurants all over the lake, most equipped with docks and buoys (See the restaurants section). There are all sorts of boating events, such as sailboat racing, firework shows over the lake, guided cruises, and more. As an interstate waterway, Lake Tahoe is subject to the United States Coast Guard. Lake Tahoe is home to Coast Guard Station Lake Tahoe.[103]

SCUBA diving is popular at Lake Tahoe, with some dive sites offering dramatic drop-offs or wall dives. Diving at Lake Tahoe is considered advanced due to the increased risk of decompression sickness (DCS) while diving at such a high altitude.[104][105]

Fred Rogers became the first person to swim the length of Lake Tahoe in 1955, and Erline Christopherson became the first woman to do so in 1962.[106][107]

Hiking and bicycling

There are numerous hiking and mountain biking trails around the lake. They range widely in length, difficulty and popularity. One of the most famous of Tahoe's trails is the Tahoe Rim Trail, a 165-mile (270-km) trail that circumnavigates the lake. Directly to the west of the lake is the Granite Chief Wilderness, which provides great hiking and wilderness camping. Also, to the southwest is the very popular Desolation Wilderness. One of the most popular trailheads used to access these popular destinations is Eagle Lake Trailhead, located near Emerald Bay on Tahoe's west shore. The Flume Trail of the east shore is one of Mountain Biking Magazine's Top 10 Trails in the U.S. There are also many paved off-road bicycle paths that meander through communities on all sides of the lake.

Gambling

Gambling is legal on the Nevada side of Lake Tahoe. Casinos, each with a variety of slot machines and table games, are located on the South Shore in Stateline, and on the North Shore in Crystal Bay and Incline Village.

When Nevada legalized gambling in 1931, the first casino at the lake had already been open for years. First built on the North Shore in Crystal Bay by Robert Sherman in 1926,[108] the Calneva cabin became the property of Norman Henry Biltz and was sold to Bill Graham and Jim McKay in 1929.

The Calneva was rebuilt after a fire in 1937 and expanded several times, most noticeably in 1969 when the high-rise hotel was built. Along the way, Frank Sinatra owned the property in the early 1960s, shared his cabins with the likes of Sam Giancana and Marilyn Monroe, and sold out at the height of the area's popularity.

Other casinos at the North Shore include the Crystal Bay Club, first built in 1937 as the Ta-Neva-Ho; the Tahoe Biltmore, and the Nugget. The Hyatt Regency is found at Incline Village.

At South Shore, Bill Harrah purchased the Stateline Country Club, which had stood since 1931 and built Harrah's Tahoe. Other casinos include Hard Rock Hotel and Casino Lake Tahoe, Harveys Lake Tahoe, Montbleu, and the Lakeside Inn.

Transportation

Lake Tahoe can be reached directly by car, and indirectly by train or air. The nearest passenger train service is the Amtrak station in Truckee, and is served by Amtrak's train, the California Zephyr, which runs daily between Chicago and the San Francisco Bay Area. The closest scheduled passenger airline service is available via the Reno-Tahoe International Airport (RNO).

Highways

Visitors can reach Lake Tahoe under ideal conditions within two hours from the Sacramento area, one hour from Reno or thirty minutes from Carson City. In winter months, chains or snow tires are often necessary to reach Tahoe from any direction. Traffic can be heavy on weekends due to tourists if not also from weather.

The primary routes to Lake Tahoe are on Interstate 80 via Truckee, U.S. Route 50, and Nevada State Route 431 via Reno. Most of the highways accessing and encircling Lake Tahoe are paved two-lane mountain roads. US 50 is a four-lane highway (from the canyon of the South Fork American River at Riverton, over the Sierra Nevada at Echo Summit, and into the Lake Tahoe Basin, is a mainly two-lane road) passing south of the lake and along part of the eastern shore.

California State Route 89 follows the western shore of the lake through the picturesque wilderness and connects camping, fishing and hiking locations such as those at Emerald Bay State Park, DL Bliss State Park and Camp Richardson. Farther along are communities such as Meeks Bay and Tahoe City. Finally, the highway turns away from the lake and heads northwest toward Truckee.

California State Route 28 completes the circuit from Tahoe City around the northern shore to communities such as Kings Beach, Crystal Bay, and into Incline Village, Nevada where the road becomes Nevada State Route 28. Route 28 returns along the eastern shore to US 50 near Spooner Lake.

Major area airports

Communities

California

- Carnelian Bay #3

- Dollar Point #4

- Kings Beach #1

- Sunnyside-Tahoe City #5

- Tahoe Vista #2

- Tahoma (partially in El Dorado County) #6

- South Lake Tahoe #7

- Tahoma (partially in Placer County) #6

Nevada

- Carson City #14

- Glenbrook #13

- Lakeridge #11

- Logan Creek #12

- Round Hill Village #8

- Skyland #10

- Stateline #17

- Zephyr Cove #9

- Crystal Bay #16

- Incline Village #15

In the media

The Ponderosa Ranch of the TV series Bonanza was formerly located on the Nevada side of Lake Tahoe.[109] The opening sequence of the TV series was filmed at the McFaul Creek Meadow, with Mount Tallac in the background. In September 2004 the Ponderosa Ranch closed its doors, after being sold to developer David Duffield for an undisclosed price.[110][111]

The 1974 film The Godfather Part II used the lakeside estate Fleur de Lac as the location of several scenes, including the elaborate First Communion celebration, the Senator's shakedown attempt of Michael, the assassination attempt on Michael, Michael disowning Fredo, Carmela Corleone's funeral, Fredo's death while fishing, and the closing scene of Michael sitting alone outside. Fleur de Lac, on the western California shore of Lake Tahoe, was formerly the Henry Kaiser estate. The surrounding lakeside area has been developed into a private gated condominium community and some of the buildings of the "Corleone compound" still exist, including the boathouse.[112]

The 2014 film Last Weekend, starring Patricia Clarkson and directed by Tom Dolby and Tom Williams, used the west shore lakefront home of Ray and Dagmar Dolby as the primary location for its interiors and exteriors. The house, built in 1929, was also the site for the exteriors for A Place in the Sun, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift.[113] The 1988 film Things Change was also filmed here.[114]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- ↑ van der Leeden; Troise; Todd (1990), The Water Encyclopedia (2nd ed.), Chelsea, MI: Lewis Publishers, pp. 198–200

- 1 2 "Amazing Lake Tahoe". Lake Tahoe Visitors Authority. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Water Quality". The League To Save Lake Tahoe. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- 1 2 "Lake Tahoe Resorts Winter sports". Porters Tahoe. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ Munson, Jeff (October 21, 2008). "In rocky economy, ski-resort jobs are seen as more than free passes". Nevada Appeal. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- 1 2 "The World's Deepest Lakes" (PDF). US Department of the Interior: National Park Service. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Deepest Lake in the World Deepest Lake in the United States". Geology.com. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Distance to the Horizon Calculator". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ Senesac, David. "Visual Line of Sight Calculations dependent on Earth's Curvature". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ Young, Andrew T. "Looming, Towering, Stooping, and Sinking". An Introduction to Green Flashes. San Diego State University. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ↑ "Lake Tahoe Trivia" (Press release). Lake Tahoe Visitors Authority. June 10, 2005. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ "USGS – National Water Information System". Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- ↑ Renda, Matthew (December 2016). "A New Year's Deluge". Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ↑ Oldow, J.S.; Aiken, C.L.V.; Hare, J. L.; Ferguson, J. F.; Hardyman, R. F. (January 2001). "Active displacement transfer and differential block motion within the central Walker Lane, western Great Basin". Geology. 29 (1): 19–22. Bibcode:2001Geo....29...19O. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0019:ADTADB>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ↑ Unruh, Jeffrey; Humphrey, James; Barron, Andrew (April 2003). "Transtensional model for the Sierra Nevada frontal fault system, eastern California". Geology. 31 (4): 327–330. Bibcode:2003Geo....31..327U. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0327:TMFTSN>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ↑ Perlman, David (September 3, 2012). "New tool to dig up fresh quake clues". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ "California-Nevada Fault Map centered at 39°N,120°W". USGS. Archived from the original on 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2012-09-18.

- ↑ Brothers, D.S.; Kent, G.M.; Driscoll, N. W.; Smith, S. B.; et al. (April 2009). "New Constraints on Deformation, Slip Rate, and Timing of the Most Recent Earthquake on the West Tahoe-Dollar Point Fault, Lake Tahoe Basin, California". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 99 (2a): 499–519. Bibcode:2009BuSSA..99..499B. doi:10.1785/0120080135.

- ↑ Maloney, J.M.; Noble, P.J.; Driscoll, N.W.; Kent, G.M.; et al. (2013). "Paleoseismic history of the Fallen Leaf segment of the West Tahoe-Dollar Point fault reconstructed from slide deposits in the Lake Tahoe Basin, California-Nevada". Geosphere. 9 (4): 1065–1090. Bibcode:2013Geosp...9.1065M. doi:10.1130/GES00877.1.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about Lake Tahoe and the Basin". Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit. Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on May 10, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Ichinose, G.A.; Anderson, J.G.; Satake, K.; Schweickert, R.A.; Lahren, M.M. (April 2000). "The potential hazard from tsunami and seiche waves generated by large earthquakes within Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada". Geophysical Research Letters. 27 (8): 1203–1206. Bibcode:2000GeoRL..27.1203I. doi:10.1029/1999GL011119.

- ↑ Gardner, J.V. (July 2000). "The Lake Tahoe debris avalanche". 15th Annual Geological Conference. Geological Society of Australia.

- ↑ "Tahoe, California – Climate Summary". Desert Research Institute. Retrieved October 31, 2008. (1903–2007 climate data)

- ↑ "Climate Data – North Lahontan Hydrologic Region". State of California, Department of Water Resources. Retrieved October 31, 2008. (30-year climate data)

- ↑ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ↑ Ryan L. Lokteff; Brett B. Roper & Joseph M. Wheaton (2013). "Do Beaver Dams Impede the Movement of Trout?" (PDF). Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 142 (4): 1114–1125. doi:10.1080/00028487.2013.797497. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ Eric Collier (1959). Three Against the Wilderness. Victoria, British Columbia: Touchwood. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-894898-54-6.

- ↑ "Trees Indigenous to Lake Tahoe". Northstar-at-Tahoe Resort. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ↑ "The Nature Conservancy: ''Rorippa subumbellata''". Natureserve. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ↑ Marcia Williamson (Oct 1992). "Tahoe's drama of the kokanee". Sunset Magazine. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ↑ Beier, P; Barrett, RH (1989). "Beaver Distribution in the Truckee River Basin, California" (PDF). California Fish and Game. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ↑ "The Beavers of the Truckee River". Tahoe Arts and Mountain Culture. July 20, 2009. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ↑ Keaven Van Lom (January 16, 2010). "This is Wildlife Management in the 21st century?". Moonshine Ink. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ↑ James, C. D.; Lanman, R. B. (Spring 2012). "Novel physical evidence that beaver historically were native to the Sierra Nevada". California Fish and Game. 98 (2): 129–132. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ R. B. Lanman; H. Perryman; B. Dolman; Charles D. James (Spring 2012). "The historical range of beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a review of the evidence". California Fish and Game. 98 (2): 65–80. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ 2ndNature; Huffman & Carpenter, Inc. (April 2010). North Canyon Creek Restoration Project: Phase I Final Report (PDF) (Report). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- 1 2 Sarah Muskopf (October 2007). The Effect of Beaver (Castor canadensis) Dam Removal on Total Phosphorus Concentration in Taylor Creek and Wetland, South Lake Tahoe, California (Thesis). Humboldt State University, Natural Resources. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- ↑ "At Lake Tahoe, a scuba diver's body is recovered after 17 years". Los Angeles Times. 2011-08-09.

- ↑ "Lake Tahoe Basin Mgt Unit – History & Culture". www.fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

- ↑ "Lake Tahoe Facts and Figures". Tahoe Regional Planning Association. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ Erwin, Gudde (2004). California Place Names: The origin and etymology of current geographical names. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4

- 1 2 3 4 5 McKean, Owen F. Railroads and Steamers of Lake Tahoe. San Mateo, California: Francis Guido. pp. 9, 14, 15, 30&31.

- 1 2 Noble, Doug. "The Early Steamers on the Lake". Doug Steps Out. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- 1 2 McLaughlin, Mark. "Sierra History: a look at Lake Tahoe's wonderful wood-powered steamship past". Sierra Sun. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ↑ "Water Delivery Projects and Facilities". Lahontan Basin Area Office. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- 1 2 Brean, Henery (May 2, 2009). "Nevada and California have a border dispute going back to 1850". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on March 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- 1 2 California v. Nevada, 44 U.S. 125 (Supreme Court of the United States 1980) ("The two straight-line segments that make up the boundary between California and Nevada were initially defined in California's Constitution of 1849. The first, the "north-south" segment, commences on the Oregon border at the intersection of the 42d parallel and the 120th meridian and runs south along that meridian to the 39th parallel. And the second, the "oblique" segment, begins at that parallel and runs in a southeasterly direction to the point where the Colorado River crosses the 35th parallel. Cal.Const., Art. XII (1849). In 1850, when California was admitted to the Union, Congress approved the 1849 Constitution, and with it California's eastern boundary. Act of Sept. 9, 1850, 9 Stat. 452.").

- ↑ "NGS Data Sheet - CALIFORNIA NEV IRON MON". Survey Marks and Datasheets. NOAA: National Geodetic Survey.

- 1 2 3 "NGS Data Sheet - INITIAL MON 1 CA NV". Survey Marks and Datasheets. NOAA: National Geodetic Survey.

- 1 2 "Granite Boundary Monument No. 1 - South Lake Tahoe, CA". Waymarking.com. Groundspeak, Inc. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

01/01/1894 by CGS (monumented)

Described by Coast and Geodetic Survey 1894 (CHS) this station was established in 1894 on the shore of Lake Tahoe, and marked by a granite stone with a copper bolt in it. The stone projects about 14 inches above ground, and was not disturbed when a granite monument was placed alongside it in June, 1899. The monument was set in concrete, and the hole was enlarged so as to include the old stone in the concrete mass. Being the first stone in the oblique boundary, it was called No. 1. The monument is of granite 6 feet long, 12 by 12 inches at the base and 6 by 6 inches at the top, weight about 850 pounds. The boundary monuments are designated as No. 1, No. 2, etc., the marks on the random line as T 1, T 2, etc., counting from Lake Tahoe. The monument has C cut on the California side, N on the Nevada side, and No. 1 marked on the NW face in black paint. - 1 2 3 Abbe, Donald (1979). "1872 California-Nevada State Boundary Marker". National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

Between 1855 and 1900, six different surveys of California's eastern boundary were made. None of them agreed as to the location of the boundary or the 120th degree of longitude. Various surveys were conducted in 1855, 1863, 1872, 1889 and 1893. The 1872 Von Schmidt survey is the only one that was clearly marked along its entire length with stone, rock, wood and iron markers. The 1872 survey also was accepted longer than any other survey before its inaccuracy became widely known. It was not until 1893 that the Von Schmidt line was found to be 1,600 to 1,800 feet too far west. However, even after 1893, the Von Schmidt line remained the accepted boundary, and is still used more today than the more accurate 1893 version. Oddly enough, both the 1872 and 1893 lines have been recognized and are used by both California and Nevada.

- ↑ Brean, Henry (April 27, 2009). "Four Corners mistake recalls long border feud between Nevada, California". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ "NGS Data Sheet - VON SCHMIDTS IRON MONUMENT". Survey Marks and Datasheets. NOAA: National Geodetic Survey.

The south face has the lettering inscribed---1872 longitude 120 west of Greenwich A.W. Von Schmidt U.S. astronomer and surveyor

- 1 2 "NGS Data Sheet - UPPER TRUCKEE". Survey Marks and Datasheets. NOAA: National Geodetic Survey.

It was placed near the old blocks that mark the astronomical station of Van Schmidt.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (1982). South Lake Tahoe, Calif.—Nev (JPEG) (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- 1 2 "18 U.S. Code § 1858 - Survey marks destroyed or removed". United States Code. United States.

Whoever willfully destroys, defaces, changes, or removes to another place any section corner, quarter-section corner, or meander post, on any Government line of survey, or willfully cuts down any witness tree or any tree blazed to mark the line of a Government survey, or willfully defaces, changes, or removes any monument or bench mark of any Government survey, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned

- ↑ "Business and Professions Code - §8771 Setting of monuments in general; monument perpetuation" (PDF). State of California.

- ↑ "36 CFR Part 800 - PROTECTION OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES". Code of Federal Regulation. United States.

- ↑ "Survey Marks and Datasheets". National Geodetic Survey. United States Department of Commerce.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey (1891). Markleeville Sheet (JPEG) (Topographic map). 1:125,000. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey (1992). South Lake Tahoe, Calif.—Nev (JPEG) (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Truckee River Chronology". Nevada Department of Conservation & Natural Resources. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ "33 CFR 2.36(a)(3)(i) - Navigable waters of the United States, navigable waters, and territorial waters". United States.

navigable waters of the United States, navigable waters, and territorial waters mean...Internal waters of the United States not subject to tidal influence that:...Are or have been used, or are or have been susceptible for use, by themselves or in connection with other waters, as highways for substantial interstate or foreign commerce, notwithstanding natural or man-made obstructions that require portage...

- 1 2 3 Kaiser Aetna v. United States, 444 US 164 (Supreme Court of the United States 4 December 1979) ("four tests for determining what constitutes navigable waters: whether the body of water (1) is subject to the ebb and flow of the tide, (2) connects with a continuous interstate waterway, (3) has navigable capacity, and (4) is actually navigable. Using these tests, courts have held that bodies of water much smaller than lakes and rivers also constitute navigable waters. Even shallow streams that are traversable only by canoe have met the test.").

- ↑ "33 CFR 2.38(a) - Waters subject to the jurisdiction of the United States; waters over which the United States has jurisdiction". United States.

Waters subject to the jurisdiction of the United States and waters over which the United States has jurisdiction mean the following waters...Navigable waters of the United States, as defined in § 2.36(a).

- ↑ "14 U.S. Code § 2 - Primary duties". United States.

The Coast Guard shall—(1) enforce or assist in the enforcement of all applicable Federal laws on, under, and over the high seas and waters subject to the jurisdiction of the United States;...(3) administer laws and promulgate and enforce regulations for the promotion of safety of life and property on and under the high seas and waters subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, covering all matters not specifically delegated by law to some other executive department

- 1 2 3 "33 CFR 329.4 - General definition". United States.

Navigable waters of the United States are those waters that are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide and/or are presently used, or have been used in the past, or may be susceptible for use to transport interstate or foreign commerce. A determination of navigability, once made, applies laterally over the entire surface of the waterbody, and is not extinguished by later actions or events which impede or destroy navigable capacity.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fogerty v. State of California, 87 Cal.App.3d 225 (Court of Appeals of California 24 November 1986) ("Littoral property owners owned the shorezone of a lake in fee simple to the low watermark of the lake in its current condition; however, their fee simple title in the shorezone was impressed with a public trust, analogous to an easement, acquired by the state pursuant to the doctrine of prescription and held for the benefit of the public for purposes of commerce, navigation, fishing, recreation, and preservation of the land in its natural state. ... The uses of land subject to the public trust over the shorezone of navigable waters are broader than actual uses of the land previously by the public. See Official Reports Annotated Here").

- 1 2 Robinson, Mark (8 March 2014). "Fact Checker: Are all Tahoe beaches public?". Reno Gazette Jounal. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

The land above the high-water mark is private property with no public access in California and Nevada

- 1 2 Cudahy, Claire (April 13, 2018). "High water level damages Lake Tahoe beachfront properties". Swift Communications, Inc. The Record Courier. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

In the Zephyr Cove neighborhood Marla Bay, beachfront properties have suffered from two years of water levels well above the lake's natural rim, which sits at an elevation of 6,223 feet. ...the U.S. District Court Water Master...is required by law to keep the water below the surface elevation of 6,229.1 feet, the federal legal limit ..."I've pleaded with the water master to drop the lake, and he said he can't — he's bound by law," said Smith.

- ↑ "USGS 10337000 LAKE TAHOE A TAHOE CITY CA". USGS Water Resources. U.S. Geological Survey.

Maximum legal limit...6,229.1; Natural rim of lake...6,223; Gage Datum...6,220

- ↑ Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 United States Reports 385, 391 (Supreme Court of the United States January 4, 1926) ("That the terms of a penal statute creating a new offense must be sufficiently explicit to inform those who are subject to it what conduct on their part will render them liable to its penalties is a well recognized requirement, consonant alike with ordinary notions of fair play and the settled rules of law, and a statute which either forbids or requires the doing of an act in terms so vague that men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to its application violates the first essential of due process of law.").

- ↑ "Newlands Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ Rancho Viejo v. Tres Amigos Viejos, 100 Cal. App. 4th 550 (Court of Appeals of California 25 July 25, 2002) ("Many activities will give rise to liability both as a trespass and a nuisance, if they result in the violation of a person's right of exclusive possession of land and also constitute an unreasonable and substantial interference with the use and enjoyment of the land. A trespass is an invasion of the interest in the exclusive possession of land, as by entry upon it. A nuisance is an interference with the interest in the private use and enjoyment of the land and does not require interference with the possession of it.").

- ↑ "42 U.S. Code § 1983 - Civil action for deprivation of rights". United States.

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress, except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable.

- ↑ "18 U.S. Code § 1001 - Statements or entries generally". United States.

whoever, in any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the Government of the United States, knowingly and willfully—(1) falsifies, conceals, or covers up by any trick, scheme, or device a material fact; (2) makes any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation; or (3) makes or uses any false writing or document knowing the same to contain any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or entry; shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 5 years...

- ↑ Coble, Christopher (1 November 2017). "Utah Nurse Gets $500,000 for False Arrest". Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ↑ "Tahoe Regional Planning Agency".

- ↑ "Friends of Lake Tahoe".

- ↑ "Pony Express Stations Across the American West". Legends of America. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ "Average Lake Tahoe Secchi Depth" (PDF). Tahoe Environmental Research Center (TERC). University of California, Davis. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Lahontan Regional Water Quality Board. "Lake Tahoe Basin Characterization & Assessment of Exemplary Programs for Water Quality Crediting and Trading Feasibility Analysis" (PDF). Water Quality Crediting and Trading Feasibility Study. Kieser and Associates. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 3, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ↑ Swift, Theodore J; Perez-Losada, Joaquim; Schladow, S. Geoffrey; Reuter, John E; Jassby, Alan D; Goldman, Charles R (2006). "Water clarity modeling in Lake Tahoe: Linking suspended matter characteristics to Secchi depth". Aquat. Sci. 68: 1–15. doi:10.1007/s00027-005-0798-x.

- ↑ "Lake Tahoe Total Maximum Daily Load Report" (PDF). California Regional Water Quality Control Board, Lahontan Region. 2010.

- ↑ Sahoo, G. B.; Schladow, S. G.; Reuter, J. E. (2010). "Effect of sediment and nutrient loading on Lake Tahoe optical conditions and restoration opportunities using a newly developed lake clarity model". Water Resources Research. 46 (10): n/a. Bibcode:2010WRR....4610505S. doi:10.1029/2009WR008447. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Tahoe: State of the Lake Report" (PDF). UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-03.

- ↑ "Lake Tahoe's clarity shows gains for a second year". Archived from the original on 2013-03-06.

- ↑ "Drought helps boost Lake Tahoe's clarity".

- ↑ Cripps, Colleen (2011-08-03). "Lake Tahoe Total Maximum Daily Load for Fine Sediment Particles, Nitrogen and Phosphorus" (PDF). Nevada Department of Conservations and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24.

- ↑ "Final EPA Approved Lake Tahoe TMDL Report". Nevada Bureau of Water Quality Planning. Archived from the original on 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Gimenez Dixon (1996). "Chasmistes cujus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2006. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved May 10, 2006. Listed as Critically Endangered (CR B1+2b v2.3)

- ↑ "Lake Tahoe Facts". Heavenly Mountain Resort. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ↑ Goldman, C.R.; M.D. Morgan; S.T. Threlkeld; N. Angeli (1979). "A Population Dynamics Analysis of the Cladoceran Disappearance from Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada". Limnology and Oceanography. 24 (2): 289–297. Bibcode:1979LimOc..24..289G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.556.6018. doi:10.4319/lo.1979.24.2.0289.

- ↑ Laila Kearney. Goldfish influx threatens to cloud pristine Lake Tahoe waters. Reuters Feb 22, 2013.

- ↑ Carl T. Hall (June 26, 2007). "Raging Tahoe Fire's Roots: 150 Years of Mismanagement". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A–1.

- ↑ "Construction Monitoring". Tahoe Regional Planning Agency. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14.

- ↑ Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, 535 U.S. 302 (Supreme Court of the United States 2002).

- ↑ "About TLOA". Tahoe Lakefront Homeowners Association. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- 1 2 "History of The League to Save Lake Tahoe". Keep Tahoe Blue. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Tahoe Environmental Research Center".

- ↑ Hartman, Joanna. "Tahoe Coast Guard changes command". tahoe.com. Sierra Sun. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ Egi, S. M.; Brubakk, Alf O. (1995). "Diving at altitude: a review of decompression strategies". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 22 (3): 281–300. ISSN 1066-2936. OCLC 26915585. PMID 7580768. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Altitude Diving". Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ "First person to swim length of Lake Tahoe reflects back on 1955 feat". Tahoe Daily Tribune. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ "First woman to swim the length of Lake Tahoe recalls 1962 adventure". Carson Now. Carson City Nevada News. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Moe, Al W. (2008). The Roots of Reno. p. 65. ISBN 9781439211991.

- ↑ "Bonanza". TVLand. Viacom International Inc. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Ponderosa Ranch". TV Acres. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Bonanza – Ponderosa Ranch". GoCalifornia.about.com. September 27, 2004. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Fleur de Lac Estates". Fleur du Lac Estates Home Owners Association. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Last Weekend' revives 1951 film site' – San Francisco Chronicle". Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ↑ Barth, Jack (1991). Roadside Hollywood: The Movie Lover's State-By-State Guide to Film Locations, Celebrity Hangouts, Celluloid Tourist Attractions, and More. Contemporary Books. Page 2. ISBN 9780809243266.

Further reading

- Becker, Andrew. "The naming of Tahoe's mountains". Tahoe.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- Byron, Earl R.; Charles R. Goldman (January 1, 1989). "Land-Use and Water Quality in Tributary Streams of Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada". Journal of Environmental Quality. 18 (1): 84–88. doi:10.2134/jeq1989.00472425001800010015x. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- Chang, C. C. Y.; J. S. Kuwabara; S. P. Pasilis (1992). "Phosphate and iron limitation of phytoplankton biomass in Lake Tahoe". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science. 49 (6): 1206–1215. doi:10.1139/f92-136.

- Coats, R. N.; Goldman, C. R. (2001). "Patterns of nitrogen transport in streams of the Lake Tahoe basin, California-Nevada". Water Resour. Res. 37 (2): 405–415. Bibcode:2001WRR....37..405C. doi:10.1029/2000wr900219.

- Coats, R. N., J. Perez-Losada, G. Schladow, R. Richards and C. R. Goldman. 2006. The Warming of Lake Tahoe. Climatic Change (In Press).

- Crippen, J. R., and B. R. Pavelka. 1970. The Lake Tahoe basin, California-Nevada U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1972.

- Gardner, James V.; Larry A. Mayer; John Hughes-Clarke (January 16, 2003). "The bathymetry of Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada". Open-File Report 98-509. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- Goldman, C. R.; Jassby, A.; Powell, T. (1989). "Interannual fluctuations in primary production: meteorological forcing at two subalpine lakes". Limnol. Oceanogr. 34 (2): 310–323. Bibcode:1989LimOc..34..310G. doi:10.4319/lo.1989.34.2.0310.

- Goldman, C. R.; Jassby, A. D.; Hackley, S. H. (1993). "Decadal, interannual, and seasonal variability in enrichment bioassays at Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada, USA". Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 50 (7): 1489–1496. doi:10.1139/f93-170.

- Hatch, L. K.; Reuter, J. E.; Goldman, C. R. (2001). "Stream phosphorus transport in the Lake Tahoe Basin, 1989–1996". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 69 (1): 63–83. doi:10.1023/a:1010752628576. PMID 11393545.

- Jensen, Carol A.; North Lake Tahoe Historical Society (2012). Lake Tahoe's West Shore. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738588919.

- Jassby, A. D.; Goldman, C. R.; Powell, T. M. (1992). "Trend, seasonality, cycle, and irregular fluctuations in primary productivity at Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada, USA". Hydrobiol. 246 (3): 195–203. doi:10.1007/bf00005697.

- Jassby, A. D.; Reuter, J. E.; Axler, R. P.; Goldman, C. R.; Hackley, S. H. (1994). "Atmospheric deposition of nitrogen and phosphorus in the annual nutrient load of Lake Tahoe (California-Nevada)". Water Resour. Res. 30 (7): 2207–2216. Bibcode:1994WRR....30.2207J. doi:10.1029/94wr00754.

- Jassby, A. D.; Goldman, C. R.; Reuter, J. E. (1995). "Long-term change in Lake Tahoe (California-Nevada, U.S.A.) and its relation to atmospheric deposition of algal nutrients". Arch. Hydrobiol. 135: 1–21.

- Jassby, A. D.; Goldman, C. R.; Reuter, J. E.; Richards, R. C. (1999). "Origins and scale dependence of temporal variability in the transparency of Lake Tahoe, California-Nevada". Limnol. Oceanog. 44 (2): 282–294. Bibcode:1999LimOc..44..282J. doi:10.4319/lo.1999.44.2.0282.

- Jassby, A.; Reuter, J.; Goldman, C. R. (2003). "Determining long-term water -quality change in the presence of climate variability: Lake Tahoe (U.S.A.)". Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 60 (12): 1452–1461. doi:10.1139/f03-127.

- Leonard, R. L.; Kaplan, L. A.; Elder, J. F.; Coats, R. N.; Goldman, C. R. (1979). "Nutrient Transport in Surface Runoff from a Subalpine Watershed, Lake Tahoe Basin, California". Ecological Monographs. 49 (3): 281–310. doi:10.2307/1942486. JSTOR 1942486.

- Nagy, M., 2003. Lake Tahoe Basin Framework Study Groundwater Evaluation Lake Tahoe Basin, California and Nevada. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Sacramento, CA.

- Naslas, G. D.; Miller, W. W.; Blank, R. R.; Gifford, G. F. (1994). "Sediment, nitrate, and ammonium in surface runoff from two Tahoe basin soil types". Water Resour. Bull. 30 (3): 409–417. Bibcode:1994JAWRA..30..409N. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.1994.tb03300.x.

- Richards, R. C.; Goldman, C. R.; Byron, E.; Levitan, C. (1991). "The mysids and lake trout of Lake Tahoe: A 25-year history of changes in the fertility, plankton, and fishery of an alpine lake". Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 9: 30–38.

- Sahoo, G. B., S. G. Schladow and J. E. Reuter, 2010. Effect of sediment and nutrient loading on Lake Tahoe optical conditions and restoration opportunities using a newly developed lake clarity model

- Schuster, S.; Grismer, M. E. (2004). "Evaluation of water quality projects in the Lake Tahoe Basin". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 90 (1–3): 225–242. doi:10.1023/b:emas.0000003591.52435.8d. PMID 15887374.

- Scott, E. B. 1957. The Saga of Lake Tahoe. Early Lore and History of the Lake Tahoe Basin

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lake Tahoe. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Lake Tahoe Data Clearinghouse – USGS/Western Geographic Science Center

- US EPA's Lake Tahoe webpage

- Truckee River Watershed Council

- Tahoe Institute for Natural Science

- Lake Tahoe remote Meteorological Data Sites

- Lake Tahoe Watershed- California Rivers Assessment database