Concord, Massachusetts

| Concord, Massachusetts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

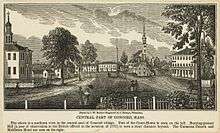

View of Concord's Main Street in December | ||

| ||

|

Motto(s): Quam Firma Res Concordia (Latin) "How Strong Is Harmony" | ||

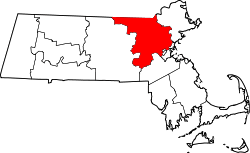

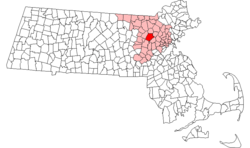

Location in Middlesex County in Massachusetts | ||

Concord, Massachusetts Location in Middlesex County in Massachusetts | ||

| Coordinates: 42°27′37″N 71°20′58″W / 42.46028°N 71.34944°WCoordinates: 42°27′37″N 71°20′58″W / 42.46028°N 71.34944°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Massachusetts | |

| County | Middlesex County | |

| Settled | 1635 | |

| Incorporated | 1635 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Open town meeting | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 25.9 sq mi (67.4 km2) | |

| • Land | 24.9 sq mi (64.5 km2) | |

| • Water | 1.0 sq mi (2.5 km2) | |

| Elevation | 141 ft (43 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 17,669 | |

| • Density | 680/sq mi (260/km2) | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) | |

| ZIP Code | 01742 | |

| Area code(s) | 351 / 978 | |

| FIPS code | 25-15060 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0619398 | |

| Website | www.concordma.gov | |

Concord (/ˈkɒŋkərd/) is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the United States. At the 2010 census, the town population was 17,668.[1] The United States Census Bureau considers Concord part of Greater Boston. The town center is located near where the confluence of the Sudbury and Assabet rivers forms the Concord River.

The area which became the town of Concord was originally known as Musketaquid, an Algonquian word for "grassy plain". It was one of the scenes of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the initial conflict in the American Revolutionary War. It developed into a remarkably rich literary center during the mid-nineteenth century. Featured were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Amos Bronson Alcott, Louisa May Alcott and Henry David Thoreau, all of whose homes are preserved in modern-day Concord. The now-ubiquitous Concord grape was developed here.

History

Prehistory and founding

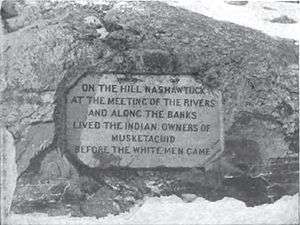

The area which became the town of Concord was originally known as "Musketaquid", situated at the confluence of the Sudbury and Assabet rivers.[2] The name Musketaquid was an Algonquian word for "grassy plain", fitting the area's low-lying marshes and kettle holes.[3] Native Americans had cultivated corn crops there; the rivers were rich with fish and the land was lush and arable.[4] However, the area was largely depopulated by the smallpox plague that swept across the Americas after the arrival of Europeans.[5]

In 1635, a group of settlers from Britain led by Rev. Peter Bulkeley and Major Simon Willard negotiated a land purchase with the remnants of the local tribe. Bulkeley was an influential religious leader who "carried a good number of planters with him into the woods";[6] Willard was a canny trader who spoke the Algonquian language and had gained the trust of Native Americans.[7] They exchanged wampum, hatchets, knives, cloth, and other useful items for the six-square-mile purchase from Old Jethro, which formed the basis of the new town, called "Concord" in appreciation of the peaceful acquisition.[2][8]

Battle of Lexington and Concord

The Battle of Lexington and Concord was the first conflict in the American Revolutionary War.[9] On April 19, 1775, a force of British Army regulars marched from Boston to Concord to capture a cache of arms that was reportedly stored in the town. Forewarned by Samuel Prescott (who had received the news from Paul Revere), the colonists mustered in opposition. Following an early-morning skirmish at Lexington, where the first shots of the battle were fired, the British expedition under the command of Lt. Col. Francis Smith advanced to Concord. There, colonists from Concord and surrounding towns (notably a highly drilled company from Acton led by Isaac Davis) repulsed a British detachment at the Old North Bridge and forced the British troops to retreat.[10] Subsequently, militia arriving from across the region harried the British troops on their return to Boston, culminating in the Siege of Boston and outbreak of the war.

The battle was initially publicized by the colonists as an example of British brutality and aggression: one colonial broadside decried the "Bloody Butchery of the British Troops."[11] A century later, however, the conflict was remembered proudly by Americans, taking on a patriotic, almost mythic status ("the shot heard 'round the world") in works like the "Concord Hymn" and "Paul Revere's Ride."[12] In 1894, the Lexington Historical Society petitioned the Massachusetts State Legislature to proclaim April 19 as "Lexington Day." Concord countered with "Concord Day." Governor Greenhalge opted for a compromise: Patriots' Day. In April 1975, Concord hosted a bicentennial celebration of the battle, featuring an address at the Old North Bridge by President Gerald Ford.[13]

Literary history

Concord has a remarkably rich literary history centered in the mid-nineteenth century around Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), who moved to the town in 1835 and quickly became its most prominent citizen.[14] Emerson, a successful lecturer and philosopher, had deep roots in the town: his father Rev. William Emerson (1769–1811) grew up in Concord before becoming an eminent Boston minister, and his grandfather, William Emerson Sr., witnessed the battle at the North Bridge from his house, and later became a chaplain in the Continental Army.[15] Emerson was at the center of a group of like-minded Transcendentalists living in Concord.[16] Among them were the author Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864) and the philosopher Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888), the father of Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888). A native Concordian, Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), was another notable member of Emerson's circle. This substantial collection of literary talent in one small town led Henry James to dub Concord "the biggest little place in America."[17]

Among the products of this intellectually stimulating environment were Emerson's many essays, including Self-Reliance (1841), Louisa May Alcott's novel Little Women (1868), and Hawthorne's story collection Mosses from an Old Manse (1846).[18] Thoreau famously lived in a small cabin near Walden Pond, where he wrote Walden (1854).[19] After being imprisoned in the Concord jail for refusing to pay taxes in political protest against slavery and the Mexican–American War, Thoreau penned the influential essay "Resistance to Civil Government", popularly known as Civil Disobedience (1849).[20] Evidencing their strong political beliefs through actions, Thoreau and many of his neighbors served as station masters and agents on the Underground Railroad.[21]

The Wayside, a house located on Lexington Road, has been home to a number of authors.[22] It was occupied by scientist John Winthrop (1714–1779) when Harvard College was temporarily moved to Concord during the Revolutionary War.[23] The Wayside was later the home of the Alcott family (who referred to it as "Hillside"); the Alcotts sold it to Hawthorne in 1852, and the family moved into the adjacent Orchard House in 1858. Hawthorne dubbed the house "The Wayside" and lived there until his death. The house was purchased in 1883 by Boston publisher Daniel Lothrop and his wife, Harriett, who wrote the Five Little Peppers series and other children's books under the pen name Margaret Sidney.[24] Today, The Wayside and the Orchard House are both museums. Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, and the Alcotts are buried on Authors' Ridge in Concord's Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.[25]

The twentieth-century composer Charles Ives wrote his Concord Sonata (c. 1904-15) as a series of impressionistic portraits of literary figures associated with the town. Concord maintains a lively literary culture to this day; notable authors who have called the town home in recent years include Doris Kearns Goodwin, Alan Lightman, Robert B. Parker, and Gregory Maguire.

Concord grape

In 1849, Ephraim Bull developed the now-ubiquitous Concord grape at his home on Lexington Road, where the original vine still grows.[26] Welch's, the first company to sell grape juice, maintains a headquarters in Concord.[27] Boston-born Ephraim Wales Bull developed the Concord grape by experimenting with seeds from some of the native species. On his farm outside Concord, down the road from the Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne and Alcott homesteads, he planted some 22,000 seedlings in all, before he had produced the ideal grape. Early ripening, to escape the killing northern frosts, but with a rich, full-bodied flavor, the hardy Concord grape thrives where European cuttings had failed to survive. In 1853, Mr. Bull felt ready to put the first bunches of his Concord grapes before the public—and won a prize at the Boston Horticultural Society Exhibition. From these early arbors, fame of Mr. Bull's ("the father of the Concord grape") Concord grape spread worldwide, bringing him up to $1,000 a cutting, but he died a relatively poor man. The inscription on his tombstone states, "He sowed--others reaped."[28]

Plastic bottle ban

On September 5, 2012, Concord became the first community in the United States to approve a ban of the sale of water in single-serving plastic bottles. The law banned the sale of PET bottles of one liter or less starting on January 1, 2013.[29] The ban provoked significant national controversy. An editorial in the Los Angeles Times characterized the ban as "born of convoluted reasoning" and "wrongheaded."[30] Some residents stated that this ban would not do much to affect the sales of bottled water, which was still highly accessible in the surrounding areas,[31] and the belief that it restricted consumers' freedom of choice.[32] Opponents also considered the ban to represent unfair targeting of one product in particular, when other, less healthy alternatives such as soda and fruit juice were still readily available in bottled form.[33][34] Nonetheless, subsequent efforts to repeal Concord's plastic bottled water ban have failed in open town meetings.[35] An effort to repeal Concord's ban on the sale of plastic water bottles was resoundingly defeated at a Town Meeting. Resident Jean Hill, who led the initial fight for the ban, said, "I really feel at the age of 86 that I've really accomplished something." Town Moderator Eric Van Loon didn't even bother taking an official tally because opposition to repeal was so overwhelming. It appeared that upwards of 80 to 90 percent of the 1,127 voters at town meeting raised their ballots against the repeal measure. The issue has been bubbling in Concord for several years. In 2010, a town meeting-approved ban, which wasn't written as a bylaw, was rejected by the state attorney general's office. In 2011, a new version of the ban narrowly failed at town meeting, by a vote of 265 to 272. The ban on selling water in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles of one liter or less passed in 2012 by a vote of 403 to 364, and a repeal effort in April failed by a vote of 621 to 687.

Geography

.jpg)

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 25.9 square miles (67 km2), of which 24.9 square miles (64 km2) is land and 1.0 square mile (2.6 km2), or 3.75%, is water. The city of Lowell is 13 miles (21 km) to the north, Boston is 19 miles (31 km) to the east, and Nashua, New Hampshire, is 23 miles (37 km) to the north.

Massachusetts state routes 2, 2A, 62, 126, 119, 111, and 117 pass through Concord. The town center is located near the confluence of the Sudbury and Assabet rivers, forming the Concord River, which flows north to the Merrimack River in Lowell. Gunpowder was manufactured from 1835 to 1940 in the American Powder Mills complex extending upstream along the Assabet River.[36]

Adjacent towns

Concord is located in eastern Massachusetts, bordered by several towns:

Government

State and federal government

On the federal level, Concord is part of Massachusetts's 3rd congressional district, represented by Niki Tsongas. The state's senior (Class I) member of the United States Senate is Elizabeth Warren. The junior (Class II) senator is Ed Markey.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1850 | 2,249 | — |

| 1860 | 2,246 | −0.1% |

| 1870 | 2,412 | +7.4% |

| 1880 | 3,922 | +62.6% |

| 1890 | 4,427 | +12.9% |

| 1900 | 5,652 | +27.7% |

| 1910 | 6,421 | +13.6% |

| 1920 | 6,461 | +0.6% |

| 1930 | 7,477 | +15.7% |

| 1940 | 7,972 | +6.6% |

| 1950 | 8,623 | +8.2% |

| 1960 | 12,517 | +45.2% |

| 1970 | 16,148 | +29.0% |

| 1980 | 16,293 | +0.9% |

| 1990 | 17,076 | +4.8% |

| 2000 | 16,993 | −0.5% |

| 2010 | 17,668 | +4.0% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States Census records and Population Estimates Program data.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46] | ||

At the 2000 census,[47] there were 16,993 people, 5,948 households and 4,437 families residing in the town. The population density was 682.0 per square mile (263.3/km2). There were 6,153 housing units at an average density of 246.9 per square mile (95.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.64% White, 2.24% African American, 0.09% Native American, 2.90% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 2.12% from other races, and 0.99% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.80% of the population.

There were 13,090 households of which 37.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.5% were married couples living together, 7.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.4% were non-families. 22.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.62 and the average family size was 3.08.

25.1% of the population were under the age of 18, 4.2% from 18 to 24, 25.8% from 25 to 44, 28.4% from 45 to 64, and 16.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 101.8 males.

In 2013, the median household income was $129,960.[48] About 2.1% of families and 3.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.7% of those under age 18 and 3.3% of those age 65 or over.

Pronunciation

The town's name is usually pronounced by its residents as /ˈkɒŋkərd/ KONG-kərd in a manner indistinguishable from the American pronunciation of the word "conquered".[49]

Economy

Principal employers

According to Concord's 2016 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[50] the principal employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Emerson Hospital | 1,731 |

| 2 | Concord Meadows Corporate Center (building complex with mulltiple tenants) | 1,050 |

| 3 | Newbury Court (senior living facility) | 290 |

| 4 | Care One at Concord (nursing and assisted living facility) | 166 |

| 5 | Middlesex School (coeducational private high school) | 197 |

| 6 | Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates | 162 |

| 7 | Concord Academy (coeducational private high school) | 165 |

| 8 | Hamilton, Brook, Smith, & Reynolds, P.C. (intellectual property law) | 75 |

Transportation

Concord station is served by the MBTA's Fitchburg Line. Yankee Line provides commuter bus service between Concord and Boston.[51]

Sister cities

Points of interest

- Barrett's Farm

- Reuben Brown House, home of notable revolutionist

- Concord Art Association

- Concord Free Public Library

- Concord Museum

- Corinthian Lodge[52]Egg Rock, where the Concord River forms at the confluence of the Sudbury River and Assabet River, accessible by water or land

- Emerson Hospital

- Ralph Waldo Emerson House

- Estabrook Woods

- Fairyland Pond

- First Parish Church[53]

- Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

- Massachusetts Correctional Institution – Concord

- Minute Man National Historical Park

- Northeastern Correctional Center

- The Old Manse, home of Emerson and Hawthorne

- Old North Bridge

- Orchard House

- Punkatasset Hill

- Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

- Walden Pond

- The Wayside, home of Louisa May Alcott, Hawthorne, and Margaret Sidney

- Wheeler-Minot Farmhouse, also known as Thoreau Farm, birthplace of Henry David Thoreau

- Wright's Tavern

Education

- Concord Carlisle Regional High School, the local public high school

- Concord Middle School (consisting of two buildings about a mile apart: Sanborn and Peabody)

- Alcott School, Willard School, and Thoreau School, the local public elementary schools

- Concord Academy and Middlesex School, private preparatory schools

- The Fenn School and The Nashoba Brooks School, private primary schools

Transportation

- Commuter rail service to Boston's North Station is provided by the MBTA with two stops in Concord on its Fitchburg Line.

- Yankee Lines provides a commuter bus service to Copley Square in Boston from Concord Center.

Notable people

- Chris Abele, county executive of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin

- Seth Abramson, poet[54]

- Amos Bronson Alcott, teacher and writer

- Louisa May Alcott, novelist

- Casper Asbjornson, Major League Baseball player

- Jane G. Austin, writer of historical fiction

- Oscar C. Badger, U.S. Navy officer[55]

- Laurie Baker, USA ice hockey gold medalist[56]

- Samuel Bartlett, silversmith

- Tim Berners-Lee, British computer scientist, best known as the inventor of the World Wide Web

- Frank Hagar Bigelow, U.S. astronomer and meteorologist

- Daniel Bliss, jurist, proscribed by the Massachusetts Banishment Act

- Paget Brewster, actress

- Peter Bulkley, Puritan preacher and a co-founder of Concord[57]

- Ephraim Bull, inventor of the Concord grape

- John Buttrick, Concord militia leader

- Steve Carell, comedian (lived in Acton but attended The Fenn School and also attended The Middlesex School)

- William Ellery Channing, poet

- Darby Conley, cartoonist

- Patricia Cornwell, contemporary American crime writer and author[58]

- George William Curtis, writer and speaker

- Bob Diamond, former chief executive of Barclays

- Harrison Gray Dyar, chemist and inventor

- Edward Waldo Emerson, physician, writer and lecturer

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, essayist, poet and philosopher

- William Emerson, minister, father of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Will Eno, author and playwright

- Richard Fadden, CSIS Director

- Allen French, author and historian (including of the history of the town)

- Daniel Chester French, sculptor

- Michael Fucito, Major League Soccer player

- Kevin Garnett, NBA player

- Hal Gill, National Hockey League player[59]

- Tom Glavine, Major League Baseball player

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian and writer[60]

- Har Gobind Khorana, Notable Indian American biochemist who shared the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine

- Richard N. Goodwin, advisor and speechwriter to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson

- William Watson Goodwin, classical scholar

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, novelist and short story writer

- Ebenezer R. Hoar, U.S. Attorney General

- George Frisbie Hoar, U.S. Congressman and Senator

- John Hoar, redeemer of famed captive Mary Rowlandson during King Philip's War

- Jonathan Hoar, colonial soldier

- Samuel Hoar, U.S. Congressman

- Frederic Hudson, journalist

- Dick Hustvedt, software engineer

- Edward Jarvis, physician and statistician

- Dick Kazmaier, Princeton American football player who was the last Ivy League Heisman Trophy winner[61]

- George Parsons Lathrop, poet and novelist

- Joel Kurtzman, economist and journalist

- Alan Lightman, physicist, novelist and essayist[62]

- Lynn Harold Loomis, mathematician and co-discoverer of the Loomis–Whitney inequality[63]

- Gregory Maguire, author[64]

- Andrew McMahon, musician and lead singer of Something Corporate and Jack's Mannequin

- Jane Mendillo, CEO of Harvard Management Company

- Russell Miller, author and historian

- William Munroe, first manufacturer of lead pencils in America

- Abigail May Alcott Nieriker, artist

- Robert B. Parker, author[65]

- Samuel Parris, clergyman and witchcraft prosecutor

- Uta Pippig, marathon runner[66]

- Samuel Prescott, American Revolutionary War "The Ride" with Paul Revere and William Dawes

- Sam Presti, NBA executive[67]

- Amelia Atwater-Rhodes, novelist

- Ezra Ripley, clergyman

- William Stevens Robinson, journalist

- Dean Rosenthal, composer and musician

- Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, journalist, author and reformer

- David Allen Sibley, ornithologist and author

- Margaret Sidney (pseudonym of Harriett Mulford Stone Lothrop), author

- Robert Solow, Nobel laureate in economics[63]

- John Augustus Stone, actor, dramatist and playwright

- Henry David Thoreau, author, naturalist and philosopher

- John Tortorella, Columbus Blue Jackets head coach

- Jonas Wheeler, Maine Senate President

- Thomas Wheeler, soldier in King Philip's War

- William W. Wheildon, writer[68]

- William Whiting, lawyer, writer and politician

- Samuel Willard, 17th century colonial minister

- Simon Willard, 17th century intellectual and former British major who co-founded Concord.

- Stephen Wolfram, British-born scientist and developer of Mathematica software

- Gordon S. Wood, historian and author[69]

- Chris Wysopal, entrepreneur and cybersecurity pioneer

Popular culture

Concord is featured in the 2012 video game Assassin's Creed 3 and the 2015 video game Fallout 4.

See also

References

- ↑ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Concord town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- 1 2 "Concord". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Native Americans, Colonial Settlement, and the Concord River". Lowell Land Trust. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Peter Bulkeley: Settlement in Concord". New England Historic Genealogical Society. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Shattuck, Lemuel (1835). "History of the Town of Concord, Mass". RootsWeb. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Moses Coit Tyler (1883). A History of American Literature, G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- ↑ "Simon Willard's Life In Concord." Marian H. Wheeler, Willard Family Association. Retrieved on July 28, 2013.

- ↑ Boston Monthly Magazine. S.L. Knapp. 1825. pp. 535–536.

- ↑ "The American Revolution begins". History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "Today In History: April 19th". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 2, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ↑ Randolph, Ryan. Paul Revere and the Minutemen of the American Revolution. The Rosen Publishing Group via Google Books. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Gioia, Dana. ""On "Paul Revere's Ride" by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow"". Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ↑ "Featured Resource: Photograph Collection 374". The State Library of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Emerson in Concord". Concord Public Library – Special Collections. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Emerson's Concord Heritage". Concord Public Library – Special Collections. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Henry David Thoreau". Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Kehe, Marjorie. "Scenes from an American Eden". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ↑ Perry, Bliss. "The American Spirit in Literature: The Transcendentalists". Authorama.com (public domain). Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Thoreau's Walden, Present at the Creation". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ McElroy, Wendy. "Henry David Thoreau and 'Civil Disobedience'". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Archived from the original on April 4, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Thoreau, Civil Disobedience, and the Underground Railroad". The Thoreau Project. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ↑ "The Wayside". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 10, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ "The Wayside: History". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ "The Wayside Authors". National Park Service. Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Lipman, Lisa. "Writers rest in Sleepy Hollow". The Globe & Mail. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Schofield, Edmund A. (1988). ""He Sowed; Others Reaped": Ephraim Wales Bull and the Origins of the 'Concord' Grape" (PDF). pp. 4–15.

- ↑ "All About Welch's: General Company Information". Welchs.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ↑ "The History". Concord Grape Association. 2014. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Llanos, Miguel. "Concord, Mass., the first US city to ban sale of plastic water bottles". NBC News. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ↑ "Concord Misfires in Plastic Bottle War". Los Angeles Times. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ "Concord, Massachusetts Bans Sale of Small Water Bottles". BBC News. BBC. 2 Jan 2013. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Weir, Richard (6 January 2013). "Battling Bottle Ban in Concord: Activists' Anger Not Kept Bottled Up". Boston Herald. p. 3. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Lefferts, Jennifer Fenn (October 13, 2013). "Concord to Revisit Ban on Water Bottles". Boston Globe. p. Region 5.

- ↑ "Nanny State Alert: Massachusetts Town Bans Bottled Water!". Fox News Insider. Fox News. 4 April 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Anderson, Leslie (5 December 2013). "Concord Town Meeting rejects repeal of plastic water bottle ban". Boston Globe. p. 3. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Mark, David A. (2014). Hidden History of Maynard. The History Press. pp. 78–82. ISBN 1626195412.

- ↑ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ↑ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Concord, Massachusetts (MA 01742) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders". www.city-data.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ "Concord". The American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ↑ "Town of Concord CAFR". concordma.gov. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ Yankee Line - Acton & Concord, MA to Boston, MA Commuter Service\ Archived 2017-08-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Corinthian Lodge Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine.. Concord, Massachusetts.

- ↑ First Parish Church Archived 2006-12-05 at the Wayback Machine.. Concord, Massachusetts.

- ↑ "Seth Abramson, MFA Blog Contributor". Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ↑

- ↑ "United States Olympic Committee – Baker, Laurie". USOC. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑

- ↑ Memmott, Carol (December 3, 2008). "Crime pays quite well for Patricia Cornwell". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Hal Gill". ESPN. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Lamb, Brian. "Booknotes: No Ordinary Time". CSPAN. Archived from the original on 2012-08-25. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ↑ "Dick Kazmaier, Heisman winner, dies". ESPN College Football. ESPN Internet Ventures. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ "Redirect". www.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- 1 2 Beecher, Norman. "Norman Beecher, 1080 Monument Street". Concord Oral History Program. Concord Free Public Library. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ "Gregory Maguire". Houghton Mifflin Books. Archived from the original on August 26, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑ Kifner, John (June 11, 1997). "He Said He Had a Pistol; Then He Flashed a Knife". New York Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ↑ English, Bella (November 3, 2004). "She's home, for the long run". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 6, 2004. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ "SONICS: Presti Named Sonics General Manager". NBA. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ↑

- ↑ "Providence College: 2007 Honorary Degree Citations". Providence College. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

Further reading

- 1871 Atlas of Massachusetts. by Wall & Gray. Map of Massachusetts. Map of Middlesex County.

- History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Volume 1 (A-H), Volume 2 (L-W) compiled by Samuel Adams Drake, published 1879-1880. 572 and 505 pages. Concord article by Rev. Grindall Reynolds in volume 1 pages 380-405.

- Lemuel Shattuck (1835). A history of the town of Concord, Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Concord: John Stacy.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Concord, Massachusetts. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Concord, Massachusetts. |

- Town of Concord official website

- Concord Public School System (includes Concord-Carlisle district)

- Chamber of Commerce

- The Concord Life, An Opportunity to Live Simply and Beautifully in Concord - Damon Street July/August 2017

- MCI-Concord, overview of Massachusetts Correctional Institution – Concord

- Concord's African American & Abolitionist History Map from the Drinking Gourd Project

- Concord, Massachusetts at Curlie (based on DMOZ)