Hudson, Massachusetts

| Hudson, Massachusetts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

Wood Square | ||

| ||

Location in Middlesex County in Massachusetts | ||

| Coordinates: 42°23′30″N 71°34′00″W / 42.39167°N 71.56667°WCoordinates: 42°23′30″N 71°34′00″W / 42.39167°N 71.56667°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Massachusetts | |

| County | Middlesex | |

| Settled | 1699 | |

| Incorporated | 1866 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Open town meeting | |

| • Executive Assistant | Thomas Moses | |

| • Board of Selectmen |

Joseph Durant Scott R. Duplisea Fred P. Lucy II James D. Quinn John Parent | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 11.8 sq mi (30.7 km2) | |

| • Land | 11.5 sq mi (29.8 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.3 sq mi (0.9 km2) | |

| Elevation | 263 ft (80 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 19,063 | |

| • Density | 1,702.6/sq mi (657.0/km2) | |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) | |

| ZIP code | 01749 | |

| Area code(s) | 351 / 978 | |

| FIPS code | 25-31540 | |

| Website |

www | |

Hudson is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, with a total population of 19,063 as of the 2010 census. Before its incorporation as a town in 1866, Hudson was a neighborhood and unincorporated village of Marlborough, Massachusetts, and was known as Feltonville. From around 1850 until the last shoe factory burned down in 1968,[1] Hudson was known as a "shoe town." At one point, the town had 17 shoe factories,[1][2] many of them powered by the Assabet River, which runs through town. Because of the many factories in Hudson, immigrants were attracted to the town. Today most people are of either Portuguese or Irish descent, with a smaller percentage of people being of French, Italian, English, or Scots-Irish descent. While some manufacturing remains in Hudson, the town is now primarily residential. Hudson is served by the Hudson Public Schools district.

History

In 1650, the area that would become Hudson was part of the Indian Plantation for the Praying Indians. The Praying Indians were evicted from their plantation during King Philip's War and most did not return after the war.[2] The first European settlement of the Hudson area occurred in 1699 when settler John Barnes, who had been granted an acre of the Ockookangansett Indian plantation the year before, built a gristmill on the Assabet River on land that would one day be part of Hudson.[1] By 1701, Barnes had also built a sawmill and bridge across the Assabet.

The settlement was part of the town (now city) of Marlborough Over time, it came to be known as Feltonville. As early as June 1743, area residents petitioned to break away from Marlborough and become a separate town, claiming the journey to attend Marlborough's town meeting was "vastly fatiguing."[1][2] Their petition was denied by the Massachusetts General Court. Men from the area fought with the Minutemen on April 19, 1775, as they harassed British troops along the route to Boston.[1][2]

In the 1850s, Feltonville received its first railroads.[1][2] There were two train stations, originally operated by the Central Massachusetts Railroad Company and later by Boston & Maine, until both of them were closed in 1965. This allowed the development of larger factories, some of the first in the country to use steam power and sewing machines. By 1860, Feltonville had 17 shoe and shoe-related factories, which attracted immigrants from Ireland and French Canada. Feltonville residents fought during the Civil War. Twenty-five of those men died doing so. Two houses, including the Goodale Homestead on Chestnut Street (Hudson's oldest building, dating from 1702) and the Curley home on Brigham Street (formerly known as the Rice Farm), have been cited as way-stations on the Underground Railroad.[2][3] Both properties remain in existence as of 2018.

In 1865, Feltonville residents once again petitioned to become a separate town. They cited the difficulty of attending town meeting, as their predecessors had in 1743, and also noted that Marlborough's high school was too far for most Feltonville children to practicably attend. This petition was approved by the Massachusetts General Court on March 19, 1866. The new town was named Hudson after Congressman Charles Hudson, who donated $500 to the new town for a public library, on the condition the town be named after him.[2][3] Congressman Hudson's affinity for the new town stemmed from his birth and childhood residence in the Feltonville neighborhood.

Over the next twenty years, Hudson grew as several industries settled in town. Two woolen mills, an elastic-webbing plant, a piano case factory, and a factory for waterproofing fabrics by rubber coating were constructed. Private banks, five schools, a poor farm, and the town hall (still in use as of 2017) were also built during this time.[2][3] The population hovered around 4,000 residents, most of whom lived in modest houses with small backyard gardens. Some of Hudson's wealthier citizens built elaborate Queen Anne Victorian mansions, and many of them still exist. One of the finest is the 1895 Col. Adelbert Mossman House on Park Street, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

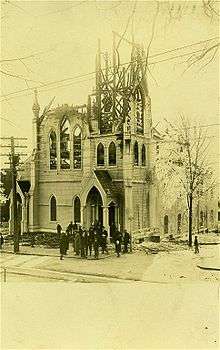

The town maintained five volunteer fire companies during the 1880s and 1890s, one of which manned the Eureka Hand Pump, a record-setting pump that could shoot a 1.5-inch (38 mm) stream of water 229 feet (70 m).[2][3] Despite this glut of fire companies, on July 4, 1894, two boys playing with firecrackers started a fire that burned down 40 buildings and 5 acres (20,000 m2) of central Hudson. Nobody was hurt, but the damages were estimated at $400,000 in 1894 (the equivalent of approximately $11.1 million in 2018).[2][3] The town was substantially rebuilt within a year or two.

By 1900, Hudson's population reached about 5,500 residents and the town had built a power plant on Cherry Street. Many houses were wired for electricity, and to this day Hudson produces its own power under the auspices of the Hudson Light and Power Department, a non-profit municipal utility owned by the town. Electric trolley lines were built that connected Hudson with the towns of Leominster, Concord, and Marlborough, though these only remained in existence until the late 1920s.[2][3] The factories in town continued to grow, attracting immigrants from England, Germany, Portugal, Lithuania, Poland, Greece, Albania, and Italy. These immigrants usually lived in boarding houses near their places of employment. In 1928, 19 languages were spoken by the workers of the Firestone-Apsley Rubber Company. Today, the majority of Hudson residents are of Irish or Portuguese descent, with lesser populations of Brazilian, Italian, French, French Canadian, English, Scots-Irish, Greek, and Polish descent. About one-third of Hudson residents are Portuguese or are of Portuguese descent.[2] Most people of Portuguese descent in Hudson are from the Azorean island of Santa Maria, with a smaller amount from the island of São Miguel or from the Trás-os-Montes region of mainland Portugal. The Portuguese community in Hudson maintains the Hudson Portuguese Club,[4] which was established in the mid-1910s and has outlived many other area ethnic clubs. In 2003 the Hudson Portuguese Club replaced its original Port Street clubhouse with a function hall and restaurant built at the same location.

Hudson's population hovered around 8,000 from the 1920s to the 1950s, when developers purchased some farms that surrounded the town center. The new houses built on this land helped double Hudson's population to 16,000 by 1970.[3] Since the 1990s high-technology companies built plants in Hudson, notably the semiconductor fabrication factory built by Digital Equipment Corporation and now owned by Intel. Although the population of Hudson is now about 20,000, the town continues the traditional town meeting form of government.[2]

Former names

Before becoming a separate incorporated town, Hudson was a neighborhood and unincorporated village within the town (now city) of Marlborough, Massachusetts. From 1656 until 1700, present-day Hudson and the surrounding area was known as the Indian Plantation or the Cow Commons.[5] From 1700 to 1800,[5] the settlement was known as The Mills.[2] From 1800 to 1828,[5] the settlement was called New City or Feltonville. The last name was derived from that of Silas Felton (1776-1828), who operated a dry goods store in the hamlet from 1801 onward and served many years as a Marlborough selectman, town clerk, town assessor, and postmaster.[2][3] Today, Felton remains immortalized in the Silas Felton Hudson Historic District and two Hudson street names: Felton Street and Feltonville Road.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 11.8 square miles (30.7rere km²), of which 11.5 square miles (29.8 km²) is land and 0.3 square mile (0.9 km²) (2.87%) is water.

The Assabet River runs prominently through most of Hudson. The river arises from wetlands in Westborough and flows northeast 34 miles (55 km), starting at an elevation of 320 feet (98 m) and descending through the towns of Northborough, Marlborough, Berlin, Hudson, Stow, Maynard, Acton, and finally Concord, where it merges with the Sudbury River to form the Concord River, at an elevation of 100 ft (30 m). The dam in central Hudson is one of nine historic mill or flood control dams on the Assabet River. The back of the Hudson Public Library parking lot provides access to launch canoes and kayaks. Downstream is the dam, but upstream provides miles of flat water—depending on the season, as far southeast as the dam at Milham Brook in Marlborough. Another canoe and kayak launch exists farther upstream behind Hudson High School, accessible via an unpaved parking lot on Chapin Street. There is also boat access downstream of the dam at Main Street Landing, accessible from the paved Assabet River Rail Trail parking lot on Main Street, and providing a few miles of paddling northeast until the mill dam in the Stow portion of Gleasondale. A significant portion of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge (opened in 2005) is located in Hudson.

On the border with Stow is Lake Boon, a popular vacation spot prior to the widespread adoption of the automobile but now a primarily residential neighborhood. On the border with Marlborough is Fort Meadow Reservoir, which at one time provided drinking water to both Hudson and Marlborough. The Town of Hudson owns and maintains Centennial Beach on the shores of Fort Meadow Reservoir. It is open to residents and non-residents for the cost of a daily or season pass, typically from June to August.

Adjacent towns

Hudson is bordered by five other towns: Bolton and Stow on the north, Marlborough on the south, Sudbury on the east, and Berlin on the west.

Villages

The neighborhood and unincorporated village of Gleasondale straddles Hudson and Stow.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1870 | 3,389 | — |

| 1880 | 3,739 | +10.3% |

| 1890 | 4,670 | +24.9% |

| 1900 | 5,454 | +16.8% |

| 1910 | 6,743 | +23.6% |

| 1920 | 7,607 | +12.8% |

| 1930 | 8,460 | +11.2% |

| 1940 | 8,042 | −4.9% |

| 1950 | 8,211 | +2.1% |

| 1960 | 9,666 | +17.7% |

| 1970 | 16,084 | +66.4% |

| 1980 | 16,408 | +2.0% |

| 1990 | 17,233 | +5.0% |

| 2000 | 18,113 | +5.1% |

| 2010 | 19,063 | +5.2% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States Census records and Population Estimates Program data.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] | ||

As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 18,113 people, 6,990 households, and 4,844 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,574.4 people per square mile (608.1/km²). There were 7,168 housing units at an average density of 623.0 per square mile (240.7/km²). The racial makeup of the town was 94.12% White, 0.91% Black or African American, 0.13% Native American, 1.40% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 1.40% from other races, and 1.98% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.06% of the population.

There were 6,990 households out of which 32.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.7% were married couples living together, 9.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.7% were non-families. 25.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 3.11.

In the town, the population was spread out with 24.0% under the age of 18, 6.7% from 18 to 24, 33.5% from 25 to 44, 23.6% from 45 to 64, and 12.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.6 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $58,549, and the median income for a family was $70,145. Males had a median income of $45,504 versus $35,207 for females. The per capita income for the town was $26,679. About 2.7% of families and 4.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.8% of those under age 18 and 8.7% of those age 65 or over.

Government

| Clerk of Courts: | Michael A. Sullivan |

|---|---|

| District Attorney: | Gerard T. Leone, Jr. |

| Register of Deeds: | Richard P. Howe, Jr. (North at Lowell) Eugene C. Brune (South at Cambridge) |

| Register of Probate: | Tara E. DeCristofaro |

| County Sheriff: | James DiPaola |

| State government | |

| State Representative(s): | Rep. Kate Hogan (D) |

| State Senator(s): | Sen. Jamie Eldridge (D) |

| Governor's Councilor(s): | Marilyn M. Petitto-Devaney (Third District) |

| Federal government | |

| U.S. Representative(s): | Niki Tsongas (D-5th District) |

| U.S. Senators: | Elizabeth Warren (D), Ed Markey (D) |

Local government

The town of Hudson has an open town meeting form of government, like most New England towns. The current executive assistant, who is an official appointed by the Board of Selectmen responsible for the day-to-day administrative affairs of the town and who functions with authority delegated to the office by the town charter and bylaws, is Thomas Moses.[15] The Board of Selectmen is a group of publicly elected officials who are the executive authority of the town. There are five positions on the Hudson Board of Selectman, currently filled by Joseph Durant, Scott R. Duplisea, John M. Parent, Fred P. Lucy II, and James D. Quinn.[16] The selectmen elect from among their membership the positions of chairman, vice-chairman, and clerk of the Board.

Technically, the county government was abolished in 1997, and former county agencies, institutions, etc., reverted to the control of the state government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. However, certain county government positions, such as District Attorney and Sheriff, do still function, except they are under the state government instead of a county government.

Education

Hudson's local public school district is Hudson Public Schools,[17] a district open to Hudson residents and through school choice to any area students. The superintendent of Hudson Public Schools is Dr. Marco C. Rodrigues. Prior to starting ninth grade Hudson students may choose to attend either Hudson High School or Assabet Valley Regional Technical High School.

Schools

- Camela A. Farley Elementary School

- Forest Avenue Elementary School

- Joseph L. Mulready Elementary School

- David J. Quinn Middle School

- Hudson High School

Private schools

- Saint Michael's School was a private Catholic primary school that served grades 1 through 8 as well as kindergarten. The original building was built around 1918, when the school was founded, and the school was administered by Saint Michael's Catholic Parish. When Hudson Catholic High School closed in 2009, Saint Michael's School moved to the former HCHS building. In May 2011 the parish announced the school would close at the end of the school year.[18] The original St. Michael's School building stood empty for a few years before the parish demolished it to expand its existing parking lot.

- Hudson Catholic High School (HCHS) was a private Catholic high school that served grades 9 through 12. It was completed in 1959 and was administered by Saint Michael's Catholic Parish. The principal was Caroline Flynn and the assistant principal was Mark Wentworth at the school's closure. The parish announced only about a month before the end of the 2008–09 school year that the school would be closed by the Boston Archdiocese due to lack of enrollment—and, as a consequence, funds—for the 2009–2010 school year.[19] The HCHS building was then used as the Saint Michael's School building, which itself closed in May 2011, and has since been demolished. The parish sold the former HCHS lot, on which now stands a Rite Aid pharmacy.[20]

- A former private Catholic school district known as Saint Michael's Schools and administered by Saint Michael's Catholic Parish closed in 2011.

Library

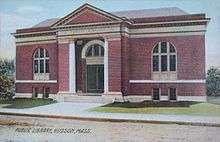

The first public library in Hudson opened in 1867 thanks to $500 in financial assistance from Charles Hudson and matching funds provided by the nascent town.[21][22] This first library was a modest reading room in the Brigham Block building and contained 721 books. In 1873 the library moved to a room in the newly-completed Hudson Town Hall. The current Hudson Public Library building is a Carnegie library first built in 1905 using a $12,500 donation from Andrew Carnegie. It opened to the public on November 16, 1905.

The original structure was a two-story Beaux-Arts design typical of Carnegie libraries and other American public buildings of the early twentieth century. Despite numerous additions over time the Carnegie building is mostly intact, including its original front entrance and handsome main stair. The town added a third story to the building in 1932 for a total cost of $15,000. Today the third floor serves as a quiet reading room, and also houses the periodicals collection, a community meeting room, and staff offices. In 1966 a two-story Modernist addition was added at the rear of the original building, more than doubling the library's size. The children's department, housed on the library's first floor, was expanded and renovated in 2002. The second floor serves as the adults' and teens' department.

The Hudson Public Library's collection has grown to approximately 65,000 books, periodicals, audio recordings, video recordings, historical records, and other items as of 2018. The library is a member of the C/W MARS regional library consortium and catalog, which allows Hudson cardholders to borrow items from other central and western Massachusetts public libraries and gives cardholders from those libraries access to Hudson's collection. In fiscal year 2008, the Town of Hudson spent 1.19% ($614,743) of its budget on its public library—about $31 per person.[23]

Religion

Houses of worship

- Saint Michael's Roman Catholic Church . St. Michael's Church, also known as St. Mike's, has existed as a congregation since 1869,[24] with its present building built in 1889.[24] The current pastor is Rev. Ron Calhoun, and the Xaverian assistant is Rev. Anthony Lalli.

- Saint Luke's Episcopal Church . St. Luke's Church was completed in 1913,[24] and the current rector is Rev. T. James Kodera.

- First United Methodist Church of Hudson . The current Methodist Church in town was completed in 1913[24] after the first one, which was located across the street from the Unitarian Church, burnt down in 1911.[24] The current pastor is Rosanne Roberts.

- Unitarian Church of Marlborough and Hudson . The Unitarian Church is technically older than the town itself; it was built in 1861.[24] The current minister is Rev. Alice Anacheka-Nasemann.

- Grace Baptist (Southern Baptist) Church .[24] Grace Baptist was founded in 1986 and moved to their current location in 1996. The congregation has grown from an original 25 to a current 1,200 members. The current (senior) pastor is Rev. Marc Pena.

- Carmel Marthoma Church.[25] The newest church in Hudson, the Carmel Marthoma Church was constructed in 2001, but the congregation traces its beginnings to the early 1970s as a prayer fellowship, meeting in the greater Boston area.

- First Federated Church (Baptist/Congregational). The First Federated Church was built in the 1960s.[24] The current pastor of the First Federated Church is Rev. James (Jay) E. Mulligan III.

- Hudson Seventh-day Adventist Church. The Seventh-day Adventist Church was also built in the 1960s.

- Hudson also has a Buddhist meeting group affiliated with the SGI.

Churches no longer in use

- Christ the King Roman Catholic Church (merged with Saint Michael's Church in 1994 to form one parish). As the parish had been suppressed in 1994 it was determined by the pastor, Fr. Walter A. Carreiro, with the Parish Pastoral Council to suspend the church building's use for worship. At the same time the St. Michael Early Childhood Center, located in a building on the same property, was relocated to Saint Michael School. The church was closed at the same time as other churches in the Boston Archdiocese were being closed to respond to the shortage of vocations and not to help pay the sex abuse lawsuits, as is often misreported. Christ the King was not closed by the Archdiocese and proceeds of its subsequent sale to the Tighe-Hamilton Funeral Home reverted directly to Saint Michael Parish. The building still exists as a memorial service chapel for Tighe-Hamilton Funeral Home.

- Union Church of All Faiths, possibly the smallest church in the United States, built by the Rev. Louis W. West[24]

A very small fraction of the town's population is Jewish and Orthodox, but there is not yet a synagogue or an Orthodox church in Hudson. Hudson nevertheless has an important role in the formation of the Albanian Orthodox Church due to the 1906 Hudson incident in which an Albanian national was refused burial by a Greek Orthodox priest from Hudson.

Notable people

- Lewis Dewart Apsley – Founder of Apsley Rubber Company; U.S. Congressman from Massachusetts from 1893 to 1897[26]

- Nuno Bettencourt – Rock musician; lead guitarist for the band Extreme[27]

- Matt Burke – Current defensive coordinator of the Miami Dolphins, raised in Hudson and graduated from Hudson High School

- Paul Cellucci – Former Governor of Massachusetts from 1997 to 2001 and former United States Ambassador to Canada from 2001 to 2005

- William D. Coolidge – Physicist who invented an improved X-ray tube, developed the tungsten filament for the incandescent light bulb, was vice-president of General Electric, and was elected to the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1975

- Hugo Ferreira – Rock musician; singer-songwriter for the band Tantric[27]

- Kevin Figueiredo – Rock drummer; drummer for the band Extreme[28]

- Tony Frias – Professional soccer player who has played for the New England Revolution, C.S. Marítimo, and S.C. Lusitânia[29]

- Evan Markopoulos – Professional wrestler of TNA Gut Check fame

- Charles Precourt – Retired U.S. astronaut[30]

- Wilbert Robinson – Born in Bolton but raised in Hudson; was a catcher for various Major League Baseball teams; best known for being manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1914 to 1931; inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945

- Paul Ryan – Born in Somerville; long-time Hudson resident until his death in 2016; comic artist on Fantastic Four and The Phantom

- Thomas P. Salmon – Former Governor of Vermont from 1973 to 1977; born in Cleveland, Ohio, raised in Stow, and attended Hudson High School

- William C. Sullivan – Former head of FBI intelligence operations

- Burton Kendall Wheeler – Former U.S. Senator from Montana from 1923 to 1947[31]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Halprin 2001: 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Halprin 2008: 7–10

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Halprin 2001: 8

- ↑ Hudson Portuguese Club (web site),

- 1 2 3 The Hudson Historical Society 1976

- ↑ "TOTAL POPULATION (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). 1: Number of Inhabitants. Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Executive Assistant". Town Departments. Town of Hudson. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Board of Selectmen". Town Departments. Town of Hudson. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ↑ Hudson Public Schools - Achievement and Character Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. Hudson.k12.ma.us. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ Jeff Malachowski (May 13, 2011). "St. Michael School in Hudson to close".

- ↑ Hudson Catholic High School closing - Articles of Faith. Boston.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ hudsoncatholic.net. hudsoncatholic.net. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ C.B. Tillinghast. The free public libraries of Massachusetts. 1st Report of the Free Public Library Commission of Massachusetts. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1891. Google books

- ↑ Retrieved November 8, 2010 Archived January 26, 2013, at Archive.is

- ↑ July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2008; cf. The FY2008 Municipal Pie: What’s Your Share? Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Board of Library Commissioners. Boston: 2009. Available: Municipal Pie Reports Archived January 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved August 4, 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Halprin 2001: 76–84

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ↑ "APSLEY, Lewis Dewart". Members of Congress: Massachusetts. Infoplease.com. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- 1 2 Jon Wiederhorn (December 30, 2003). "Tantric's Pain, Pal Nuno Bettencourt Help Create 'Hey Now'". MTV. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ↑ Evans Drumheads. "Kevin Figueiredo, Artist Detail". Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Revolution Signs Midfielder Tony Frias III". New England Revolution. April 13, 2003. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Charles J. Precourt—Biographical Data". NASA; Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ "WHEELER, Burton Kendall". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. U.S. Congress. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

References

- Halprin, Lewis; The Hudson Historical Society (2001) [First published 1999]. Images of America: Hudson. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0073-9.

- Halprin, Lewis; The Hudson Historical Society (2008). Postcard History Series: Hudson. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6284-1.

- The Hudson Historical Society (1976). Hudson Bicentennial Scrapbook. Private publication.

Further reading

- Verdone, William L., and Lewis Halprin. (2005). Images of America: Hudson's National Guard Militia. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-4456-6.

- Halprin, Lewis, and Alan Kattelle. (1998). Images of America: Lake Boon. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-1292-2.

- 1871 Atlas of Massachusetts. by Wall & Gray. Map of Massachusetts. Map of Middlesex County.

- History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Volume 1 (A-H), Volume 2 (L-W) compiled by Samuel Adams Drake, published 1879–1880. 572 and 505 pages. Hudson article by Charles Hudson in volume 1 pages 496–505.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hudson, Massachusetts. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about Hudson, Massachusetts. |

- Town of Hudson

- Hudson Public Library

- Town Profile on Massachusetts State Website

- 1870s Map of Hudson, 1 of 2

- 1870s Map of Hudson, 2 of 2

- Hudson, MA at Google Maps