Williamson County, Tennessee

| Williamson County, Tennessee | ||

|---|---|---|

Williamson County Courthouse in Franklin | ||

| ||

|

Location in the U.S. state of Tennessee | ||

Tennessee's location in the U.S. | ||

| Founded | October 26, 1799 | |

| Named for | Hugh Williamson[1] | |

| Seat | Franklin | |

| Largest city | Franklin | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 584 sq mi (1,513 km2) | |

| • Land | 583 sq mi (1,510 km2) | |

| • Water | 1.2 sq mi (3 km2), 0.2% | |

| Population (est.) | ||

| • (2016) | 219,107 | |

| • Density | 376/sq mi (145/km2) | |

| Congressional district | 7th | |

| Time zone | Central: UTC−6/−5 | |

| Website |

williamsoncounty-tn | |

Williamson County is a county in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 205,226.[2] The county seat is Franklin.[3] The county is named after Hugh Williamson, a North Carolina politician who signed the U.S. Constitution. Adjusted for relative cost of living, Williamson County is one of the wealthiest counties in the United States.[4]

Williamson County is part of the Nashville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Franklin, TN Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Pre-Civil War

The Tennessee General Assembly created Williamson County on October 26, 1799, from a portion of Davidson County. The county had originally been inhabited by at least five Native American cultures, including tribes of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Shawnee. It is home to two Mississippian-period mound complexes, the Fewkes site and the Old Town site, built by a culture that preceded such tribes.

White settlers had arrived in the area by 1798, preceded by traders. Most were from Virginia and North Carolina, part of a western movement after the American Revolutionary War. In 1800, Abram Maury laid out Franklin, the county seat, which was carved out of part of a land grant he had purchased from Major Anthony Sharp.[1] "The county was named in honor of Dr. Hugh Williamson of North Carolina, a colonel in the North Carolina militia and served three terms in the Continental Congress."[5]

Many of the early inhabitants of the county were veterans who had been paid in land grants after the Revolutionary War. Many veterans chose not to settle in the area and sold large sections of their land grants to speculators. These in turn subdivided the land and sold off smaller lots. Prior to the Civil War, the county was the second-wealthiest in the state, as part of the Middle Tennessee region. This area's resources of timber and rich soil (farmed for a diversity of crops including rye, corn, oats, tobacco, hemp, potatoes, wheat, peas, barley, and hay) provided a stable economy, as opposed to reliance on one cash crop.[5] Slavery was an integral part of the local economy. By 1850, there were 13,000 slaves in the county, making up nearly half the population of more than 27,000. (See table below)[6]

Civil War

Williamson County was severely affected by the war. Three battles were fought within the county: the Battle of Brentwood,[7] the Battle of Thompson's Station,[8] and the Battle of Franklin, which had some of the highest fatalities of the war.[9] The large plantations that were part of the economic foundation of the county were ravaged, and many of the county's youth were killed during the war.[5] Many Confederate casualties of the Battle of Franklin were buried in the McGavock Confederate Cemetery near the Carnton plantation house. This cemetery, containing the bodies of 1,481 soldiers, is the largest private Confederate cemetery in America.[1]

Post-Reconstruction to present

The agricultural and rural nature of the county continued as the basis of its economy into the early 1900s. "Most residents were farmers who raised corn, wheat, cotton and livestock."[5]

In the post-Reconstruction era and into the early 20th century, white violence against African Americans increased in an effort to assert dominance. A total of five African Americans were lynched by white mobs in Williamson County.[10] Among them was Amos Miller, a twenty-three-year-old black man taken from the courtroom during his 1888 trial as a suspect in an assault case, and hanged from the balcony of the county courthouse.[11] In 1924, fifteen-year-old Samuel Smith was lynched in Nolensville for shooting and wounding a white grocer. He was taken from a Nashville hospital by a mob and brought back to the town to be murdered. He was the last recorded lynching victim in the Nashville area.[12]

Numerous blacks left Williamson County from 1880 through 1950, contributing to the population decline. They left as part of the Great Migration to industrial cities in the North and Midwest for work and to escape Jim Crow oppression and violence. County population did not surpass that of 1880 until 1970, when it began to develop suburban housing in response to growth in Nashville.

One of the first major manufacturers to establish operations in the county was the Dortch Stove works, which opened a factory in Franklin. The factory was later developed as a Magic Chef factory, producing electric and gas ranges. (Magic Chef was prominent in the Midwest from 1929.) When the factory was closed due to extensive restructuring in the industry, this structure fell into disuse. The factory complex was restored in the late 1990s in an adaptation for offices. It is considered a "model historic preservation adaptive reuse project."[1]

The completion of the Interstate Highway System contributed to the rapid expansion of Nashville, Tennessee since the mid-20th century. These factors have stimulated tremendous population growth in Williamson County. As residential suburban population has increased, the formerly rural county has had to invest in infrastructure and schools, and its character is rapidly changing. Between 1990 and 2000, the county's population increased 56.3 percent, mostly in the northern part of the county, including the cities of Franklin and Brentwood. As of Census estimates in 2012, Franklin has more than 66,000 residents (a five-fold increase since 1980), and it ranks as the eighth-largest city in the state. Its residents are affluent, with a high median income. The land in the southern part of the county is still primarily rural and used for agriculture. Spring Hill is a growing city in this area.[1]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 584 square miles (1,510 km2), of which 583 square miles (1,510 km2) is land and 1.2 square miles (3.1 km2) (0.2%) is water.[13] The Harpeth River and its tributary, the Little Harpeth River, are the county's primary streams.

Adjacent counties

- Davidson County (north)

- Rutherford County (east)

- Marshall County (southeast)

- Maury County (south)

- Hickman County (southwest)

- Dickson County (northwest)

- Cheatham County (north)

National protected area

State protected areas

- Carter House State Historic Site

- Haley-Jaqueth Wildlife Management Area

Demographics

The county population decreased from a high in 1880 over most of the next several decades, due in large part to African Americans moving to towns and cities for work, or out of the area altogether. The oppression of Jim Crow and related violence, and the decline in the need for farm labor in the early 20th century, as mechanization was adopted, resulted in many blacks leaving Tennessee for industrial cities of the North and Midwest in the Great Migration.

The total 1880 county population was not surpassed until 1970. Combined with the rapid increase in white newcomers in new suburban developments in the county since the late 20th century, African Americans now constitute a small minority.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 2,868 | — | |

| 1810 | 13,153 | 358.6% | |

| 1820 | 20,640 | 56.9% | |

| 1830 | 26,638 | 29.1% | |

| 1840 | 27,006 | 1.4% | |

| 1850 | 27,201 | 0.7% | |

| 1860 | 23,827 | −12.4% | |

| 1870 | 25,328 | 6.3% | |

| 1880 | 28,313 | 11.8% | |

| 1890 | 26,321 | −7.0% | |

| 1900 | 26,429 | 0.4% | |

| 1910 | 24,213 | −8.4% | |

| 1920 | 23,409 | −3.3% | |

| 1930 | 22,845 | −2.4% | |

| 1940 | 25,220 | 10.4% | |

| 1950 | 24,307 | −3.6% | |

| 1960 | 25,267 | 3.9% | |

| 1970 | 34,330 | 35.9% | |

| 1980 | 58,108 | 69.3% | |

| 1990 | 81,021 | 39.4% | |

| 2000 | 126,638 | 56.3% | |

| 2010 | 183,182 | 44.7% | |

| Est. 2016 | 219,107 | [14] | 19.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] 1790-1960[16] 1900-1990[17] 1990-2000[18] 2010-2014[2] | |||

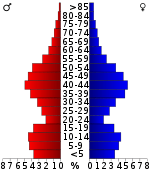

As of the census[20] of 2010, there were 183,182 people. In 2000 there were 44,725 households, and 35,780 families residing in the county. The population density was 217 per square mile (84/km2). There were 47,005 housing units at an average density of 81 per square mile (31/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 91.55% White, 5.18% Black or African American, 0.20% Native American, 1.25% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.97% from other races, and 0.82% from two or more races. 2.52% of the population were Hispanics or Latinos of any race.

There were 44,725 households in 2000 out of which 43.00% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 69.80% were married couples living together, 7.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 20.00% were non-families. 16.60% of all households were made up of individuals and 4.50% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.81 and the average family size was 3.18.

The age distribution was 29.50% under the age of 18, 6.20% from 18 to 24, 31.60% from 25 to 44, 24.90% from 45 to 64, and 7.70% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.00 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.70 males.

In 2008, the median income for a household in the county was $88,316, and the median income for a family was $101,444.[21] Also in 2008, the per capita income for the county was $42,786. About 3.50% of families and 4.70% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.40% of those under age 18 and 8.90% of those age 65 or over.

Williamson County is ranked among the wealthiest counties in the country. In 2006 it was the 17th-wealthiest county in the country according to the U.S. Census Bureau, but the Council for Community and Economic Research ranked Williamson County as America's wealthiest county (1st) when the local cost of living was factored into the equation with median household income.[22] In 2010, Williamson County is listed 17th on the Forbes list of the 25 wealthiest counties in America.[23]

By 2006 Williamson County had a population of 160,781 representing 27.0% population growth since 2000. The census bureau lists Williamson as one of the 100 fastest-growing counties in the United States for the period 2000–2005.

Government and politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 64.2% 68,212 | 29.2% 31,013 | 6.6% 7,046 |

| 2012 | 72.6% 69,850 | 26.1% 25,142 | 1.3% 1,233 |

| 2008 | 69.1% 64,858 | 29.7% 27,886 | 1.2% 1,092 |

| 2004 | 72.1% 57,451 | 27.3% 21,732 | 0.6% 467 |

| 2000 | 66.6% 38,901 | 32.1% 18,745 | 1.3% 783 |

| 1996 | 61.0% 27,699 | 33.6% 15,231 | 5.4% 2,446 |

| 1992 | 54.8% 22,015 | 32.5% 13,053 | 12.8% 5,127 |

| 1988 | 72.3% 20,847 | 27.3% 7,864 | 0.4% 112 |

| 1984 | 71.9% 17,975 | 27.7% 6,929 | 0.4% 93 |

| 1980 | 55.0% 11,597 | 41.8% 8,815 | 3.2% 683 |

| 1976 | 48.4% 7,880 | 50.3% 8,183 | 1.3% 203 |

| 1972 | 71.5% 7,556 | 24.8% 2,616 | 3.7% 392 |

| 1968 | 28.7% 2,788 | 21.2% 2,063 | 50.1% 4,867 |

| 1964 | 34.8% 2,707 | 65.2% 5,075 | |

| 1960 | 37.3% 2,699 | 61.9% 4,471 | 0.8% 58 |

| 1956 | 31.9% 1,979 | 67.2% 4,174 | 0.9% 58 |

| 1952 | 36.2% 2,326 | 63.5% 4,085 | 0.3% 19 |

| 1948 | 14.4% 556 | 59.4% 2,294 | 26.2% 1,011 |

| 1944 | 18.4% 602 | 81.3% 2,656 | 0.3% 10 |

| 1940 | 13.5% 505 | 85.8% 3,215 | 0.7% 26 |

| 1936 | 9.4% 286 | 90.5% 2,769 | 0.1% 4 |

| 1932 | 8.5% 261 | 90.0% 2,777 | 1.6% 49 |

| 1928 | 30.3% 693 | 69.7% 1,595 | |

| 1924 | 12.6% 242 | 84.9% 1,626 | 2.5% 48 |

| 1920 | 32.1% 946 | 67.9% 2,004 | |

| 1916 | 22.7% 600 | 77.0% 2,036 | 0.4% 10 |

| 1912 | 25.9% 797 | 71.8% 2,205 | 2.3% 71 |

As may be seen by the table on county voting in presidential elections, from 1964 to 1972, the majority of voters shifted in this period from the Democratic Party, which had long dominated county and state politics, to the Republican Party.

The chief executive officer of Williamson County's government is the County Mayor, who is popularly elected at-large for a four-year term. This position is responsible for the county's fiscal management and its day-to-day business. Rogers C. Anderson has served in this capacity since 2002.

The County Mayor is assisted by directors of the Agricultural Exposition Park, Animal Control, Budget & Purchasing, Community Development, County Archives, Employee Benefits, Human Resources, Information Technology, Parks & Recreation, Emergency Management, Public Safety, Property Management, Risk Management, Solid Waste Management and WC-TV.[25]

The Mayor works closely with the 24-member Board of County Commissioners, two members elected from each of the 12 voting districts of roughly equal populations. They are popularly elected by each district for a four-year term. A Chairman conducts the meetings of the Board, who is elected by the membership, annually. In addition for approval and oversight of the fiscal budget, the Board of Commissioners appoints the members of the Planning Commission, Highway Commission, Beer Board, Board of Zoning Appeals, Building Board of Adjustments, County Records Committee, Library Board and others.

| Dist. | Commissioner | Dist. | Commissioner | Dist. | Commissioner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dwight Jones | 5 | Lewis W. Green Jr. | 9 | Sherri Clark |

| 1 | Ricky D. Jones | 5 | Thomas W. "Tommy" Little | 9 | Todd Kaestner |

| 2 | Elizabeth C. "Betsy" Hester | 6 | Paul Webb | 10 | Matt Williams |

| 2 | Judy Herbert | 6 | Jeff Ford | 10 | David Landrum |

| 3 | David Pair | 7 | Bert Chalfant | 11 | Brandon Ryan |

| 3 | Matt Milligan | 7 | Tom Bain | 11 | Brian Bethard |

| 4 | Kathy Danner | 8 | Barb Sturgeon | 12 | Dana Ausbrooks |

| 4 | Gregg Lawrence | 8 | Jack Walton | 12 | Steve Smith |

| Office | Office Holder | Office | Office Holder |

|---|---|---|---|

| County Mayor | Rogers C. Anderson | County Clerk | Elaine Anderson |

| Property Assessor | Brad Coleman | Register of Deeds | Sadie Wade |

| Trustee | Karen Paris | Sheriff | Jeff Long |

| Circuit Court Clerk | Debbie Barrett | Chancery Court Clerk | Elaine Beeler |

| Juvenile Court Judge | Sharon Guffee | Juvenile Court Clerk | Brenda Hyden |

| General Sessions Judge | Denise Andre | General Sessions Judge | Tom Taylor |

| Highway Superintendent | Eddie Hood | Election Administrator | Chad Gray |

The County's Assessor of Property, County Clerk, Circuit Court Clerk, Juvenile Court Clerk, Register of Deeds, Sheriff, Trustee and two judges of the General Sessions Court are popularly elected for four-year terms. Other officials including the Chancery Court Clerk, Election Administrator, and Highway Superintendent are appointed for four-year terms. The latter two are appointed respectively by the Election Commission and Highway Commission, and the Chancery Court Clerk is appointed by the elected judges of Tennessee's 21st Judicial District.

Education

K-12 public education in the county is under the jurisdiction of Williamson County Schools, which operates 47 schools.

Higher education

- Belmont University, Williamson County Campus

- Columbia State Community College, Franklin Campus

- King University, Nashville Campus

- O'More College of Design

- University of Phoenix, Franklin Learning Center

- Williamson College

Communities

Cities

- Brentwood

- Fairview

- Franklin (county seat)

- Spring Hill (partly in Maury County)

Towns

Unincorporated communities

- Allisona (partial)

- Arrington

- Berry's Chapel

- Bethesda

- Bethlehem

- Boston

- Brush Creek

- Burwood

- College Grove

- Clovercroft

- Cool Springs

- Fernvale

- Grassland

- Kirkland

- Leiper's Fork

- Liberty Hill

- Peytonsville

- Primm Springs

- Rudderville

- Southall

- Triune

See also

Notable people

- John A. Murrell (1806?-1844), bandit, known for the Mystic Clan or Mystic Confederacy and Murrell Insurrection Conspiracy

Further reading

- Holladay, Robert, "'Dangerous Doctrines': The Rise and Fall of Jacksonian Support in Williamson County, Tennessee," Southern Studies, 16 (Spring–Summer 2009), 90–121.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 John E. Acuff, "Williamson County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 24 April 2013.

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomason Associates and Tennessee Historical Commission (February 1988). "Historic Resources of Williamson County (Partial Inventory of Historic and Architectural Properties), National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination". National Park Service.

- ↑ Simpson, John A. (2003). Edith D. Pope and Her Nashville Friends: Guards of the Lost Cause in the Confederate Veteran. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. p. 4. ISBN 9781572332119. OCLC 428118511.

- ↑ "Battle Summary: Brentwood, TN". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ "Battle Summary: Thompson's Station, TN". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ "Battle Summary: Franklin, TN". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Lynching in America/ Supplement: Lynchings by County, Equal Justice Initiative, 2017, 3rd edition, p. 6

- ↑ "Old Williamson County Courthouse - Public Square", Visit Franklin website

- ↑ Deane, Natasha (June 5, 2017). "Memorial Marker for Lynching Victims". St Anselm Episcopal Church. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ↑ Based on 2000 census data

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ "Williamson County, Tennessee - Fact Sheet - American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Cost of Living Can Significantly Affect “Real” Median Household Income Archived 2008-07-02 at the Wayback Machine., Council for Community and Economic Research website . Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Forbes: Williamson 17th richest county - Nashville Business Journal". Nashville.bizjournals.com. 2010-03-10. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ↑ Williamson County Organizational Plan, Williamson County official website. Retrieved: 20 November 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Williamson County, Tennessee. |