Murfreesboro, Tennessee

| Murfreesboro, Tennessee | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Murfreesboro | ||

From top left, cannon at Stones River National Battlefield, Rutherford County Courthouse, City Center, MTSU's Paul W. Martin Sr. Honors Building, Battle of Stones River. | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): "The 'Boro" | ||

| Motto(s): Creating a better quality of life. | ||

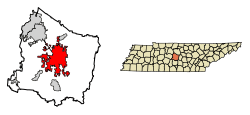

Location of Murfreesboro in Rutherford County, Tennessee. | ||

Murfreesboro, Tennessee Location of Murfreesboro in Rutherford County, Tennessee. | ||

| Coordinates: 35°50′46″N 86°23′31″W / 35.84611°N 86.39194°WCoordinates: 35°50′46″N 86°23′31″W / 35.84611°N 86.39194°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Tennessee | |

| County | Rutherford | |

| Settled | 1811 | |

| Incorporated | 1817 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Mayor–Council | |

| • Mayor | Shane McFarland (R)[1] | |

| • Vice mayor | Madelyn Scales Harris[2] | |

| Area[3] | ||

| • City | 58.47 sq mi (151.43 km2) | |

| • Land | 58.32 sq mi (151.06 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.15 sq mi (0.37 km2) 0.25% | |

| Elevation | 610 ft (186 m) | |

| Population (2010)[4] | ||

| • City | 108,755 | |

| • Estimate (2017)[4] | 136,372 | |

| • Rank | US: 205th | |

| • Density | 1,900/sq mi (720/km2) | |

| • Urban | 133,228 (US: 241st) | |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) | |

| ZIP Codes | 37127-37133 | |

| Area code(s) | 615, 629 | |

| FIPS code | 47-51560 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 1295105[5] | |

| Website | City of Murfreesboro | |

Murfreesboro is a city in, and the county seat of, Rutherford County,[6] Tennessee, United States. The population was 108,755 according to the 2010 census, up from 68,816 residents certified in 2000. In 2017, census estimates showed a population of 136,372.[4] The city is the center of population of Tennessee,[7] located 34 miles (55 km) southeast of downtown Nashville in the Nashville metropolitan area of Middle Tennessee. It is Tennessee's fastest growing major city and one of the fastest growing cities in the country.[8] Murfreesboro is also home to Middle Tennessee State University, the second largest undergraduate university in the state of Tennessee, with 22,729 total students as of fall 2014.[9]

In 2006, Murfreesboro was ranked by Money as the 84th best place to live in the United States, out of 745 cities with a population over 50,000.[10][11]

History

In 1811, the Tennessee State Legislature established a county seat for Rutherford County. The town was first named "Cannonsburgh" in honor of Newton Cannon, then Rutherford County's member of the state legislature, but it was soon renamed "Murfreesboro" for Revolutionary War hero Colonel Hardy Murfree.[12] Author Mary Noailles Murfree was his great-granddaughter.

As Tennessee settlement expanded to the west, the location of the state capital in Knoxville became inconvenient for most newcomers. In 1818, Murfreesboro was designated as the capital of Tennessee. Eight years later, however, it was itself replaced by Nashville.[13]

Civil War

On December 31, 1862, the Battle of Stones River, also called the Battle of Murfreesboro, was fought near the city between the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of Tennessee. This was a major engagement of the American Civil War, and between December 31 and January 2, 1863, the rival armies suffered a combined total of 23,515 casualties.[14] It was the bloodiest battle of the war by percentage of casualties.

Following the Confederate retreat after the drawn Battle of Perryville in central Kentucky, the Confederate army moved through East Tennessee and then turned northwest to defend Murfreesboro. General Braxton Bragg's veteran cavalry successfully harassed Union General William Rosecrans' troop movements, capturing and destroying many of his supply trains. However, they could not completely prevent supplies and reinforcements from reaching Rosecrans. Despite the large number of casualties, the battle was inconclusive. Nevertheless, it is usually considered a Union victory, since afterwards General Bragg retreated 36 miles (58 km) south to Tullahoma. Even so, the Union army did not move against Bragg until a full six months later in June 1863. The battle was significant since it did provide the Union army with a base to push the eventual drive further south, which allowed the later advances against Chattanooga and Atlanta. These eventually allowed the Union to divide the Eastern and Western theaters, followed by Sherman's March to the Sea. The Stones River National Battlefield is now a national historical site.

General Rosecrans' move to the south depended on a secure source of provisions, and Murfreesboro was chosen to become his supply depot. Soon after the battle, Brigadier General James St. Clair Morton, Chief Engineer of the Army of the Cumberland, was ordered to build Fortress Rosecrans, some 2 miles (3.2 km) northwest of the town. The fortifications covered about 225 acres (0.91 km2) and were the largest built during the war. Fortress Rosecrans consisted of eight lunettes, four redoubts and connecting fortifications. The Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad and the West Fork of the Stones River both passed through the fortress, while two roads provided additional transportation.

The fort's interior was a huge logistical resource center, including sawmills, warehouses, quartermaster maintenance depots, ammunition magazines, and living quarters for the 2,000 men who handled the operations and defended the post. The fortress was completed in June 1863, and only then did Rosecrans dare to move south.[15] The fortress was never attacked, in part because the Union troops held the town of Murfreesboro hostage by training their artillery on the courthouse. Major portions of the earthworks still exist and have been incorporated into the battlefield site.

Post-Civil War

Murfreesboro had begun as a mainly agricultural community, but by 1853 the area was home to several colleges and academies, gaining the nickname the "Athens of Tennessee". Despite the wartime trauma, the town's growth had begun to recover by the early 1900s, in contrast to other areas of the devastated South.

In 1911, the state legislature created Middle Tennessee State Normal School, a two-year institute to train teachers. It would soon merge with the Tennessee College for Women. In 1925 the Normal School was expanded to a four-year college. In 1965 it became Middle Tennessee State University.[16] MTSU now has the largest undergraduate enrollment in the state, including many international students.

World War II resulted in Murfreesboro diversifying into industry, manufacturing, and education. Growth has been steady since that time, creating a stable economy.

Murfreesboro has enjoyed substantial residential and commercial growth, with its population increasing 123.9% between 1990 and 2010, from 44,922 to 100,575.[17] The city has been a destination for many immigrants leaving areas affected by warfare; since 1990 numerous Somalis and Kurds from Iraq have settled here. The city has also become more cosmopolitan by attracting more numerous international students to the university.

Government

The city council has six members, all elected at-large for four-year terms, on staggered schedules with elections every two years. The mayor is elected at large. City council members have responsibilities for various city departments.

- Joshua Haskell, 1818[18][19]

- David Wendel, 1819

- Robert Purdy, 1820

- Henry Holmes, 1821

- W. R. Rucker, 1822-1823

- John Jones, 1824

- Wm. Ledbetter, 1825, 1827

- John Smith, 1828, 1830

- Edward Fisher, 1829, 1836, 1839

- James C. Moore, 1831

- Charles Ready, 1832

- Charles Niles, 1833

- Marman Spence, 1834

- M. Spence, 1835

- L. H. Carney, 1837

- Edwin Augustus Keeble, 1838, 1855

- G. A. Sublett, 1840

- B. W. Farmer, 1841-1842, 1845-1846

- Henderson King Yoakum, 1843

- Wilson Thomas, 1844

- John Leiper, 1847-1848

- Charles Ready, 1849-1853, 1867

- F. Henry, 1854

- Joseph B. Palmer, 1856-1859

- John W. Burton, 1860-1861

- John E. Dromgoole, 1862

- James Monro Tompkins, 1863-1864

- R. D. Reed, 1865-1866

- E. L. Jordan, 1868-1869

- Thomas B. Darragh, 1870

- Joseph A. January, 1871

- I. B. Collier, 1872-1873

- J. B. Murfree, 1874-1875

- H. H. Kerr, 1876

- H. H. Clayton, 1877

- N. C. Collier, 1878-1879

- Jas. Clayton, 1880-1881

- E. F. Burton, 1882-1883

- J. M. Overall, 1884-1885

- H. E. Palmer, 1886-1887

- Tom H. Woods, 1888-1895

- J. T. Wrather, 1896-1897

- J. O. Oslin, 1898-1899

- J. H. Chrichlow, 1900-1909

- G. B. Giltner, 1910-1918

- N. C. Maney, 1919-1922, 1932-1934

- Al D. McKnight, 1923-1931

- W. T. Gerhardt, 1934-1936, 1941-1942

- W. A. Miles, 1937-1940, 1943-1946

- John T. Holloway, 1947-1950

- Jennings A. Jones, 1951-1954

- A. L. Todd, Jr., 1955-1964

- William Hollis Westbrooks, 1965-1982[20]

- Joe B. Jackson, 1982-1998[21][22]

- Richard Reeves, 1998-2002[20]

- Tommy Bragg, 2002-2014[23]

- Shane McFarland, 2014–present[24]

Geography

Murfreesboro is located at 35°50′46″N 86°23′31″W / 35.846143°N 86.392078°W.[25]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 39.2 square miles (102 km2). 39.0 square miles (101 km2) of it is land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) of it (0.54%) is water. However, as of 2013 the city reports its total area as 55.94 square miles (144.9 km2).[26]:23

Murfreesboro is the geographic center of the state of Tennessee. A stone monument marks the official site on Old Lascassas Pike, about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) north of MTSU.

The West Fork of the Stones River flows through Murfreesboro. A walking trail, the Greenway, parallels the river for several miles. A smaller waterway, Lytle Creek, flows through downtown including historic "Cannonsburgh Village". Parts of the 19-mile (31 km) long creek suffer from pollution due to the urban environment and its use as a storm-water runoff.[27]

Murfreesboro is home to a number of natural and man-made lakes plus several small wetlands including Todd's Lake and the Murfree Spring wetland area.[28][29]

Murfreesboro has been in the path of destructive tornados several times. On April 10, 2009, an EF4 tornado struck the fringes of Murfreesboro. As a result, two people were killed and 41 others injured. 117 homes were totally destroyed, and 292 had major damage. The tornado is estimated to have caused over $40 million in damage.[30]

Transportation

Murfreesboro is served by Nashville International Airport (IATA code BNA), Smyrna Airport (MQY) and Murfreesboro Municipal Airport (MBT). The city also benefits from several highways running through the city, including Interstates 24 and 840; U.S. Routes 41, 70S, and 231; and State Routes 1, 2, 10, 96, 99, and 268. Industry also has access to North-South rail service with the rail line from Nashville to Chattanooga.

Public transportation

Since April 2007, the City of Murfreesboro has established a new transportation system with nine small buses, each capable of holding sixteen people and including two spaces for wheelchairs. The system is called "Rover"; the buses are bright green with "Rover" and a cartoon dog painted on the side. Buses operate in six major corridors: Memorial Boulevard, NW Broad Street, Old Fort Parkway, South Church Street, Mercury Boulevard and Highland Avenue.

A one-way fare is US$1.00 for adults, US$0.50 for children 6–16 and seniors 65 and over, and free for children under 6. The system operates Monday to Friday, 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.[31][32]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 1,917 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,861 | 49.2% | |

| 1870 | 3,502 | 22.4% | |

| 1880 | 3,800 | 8.5% | |

| 1890 | 3,739 | −1.6% | |

| 1900 | 3,999 | 7.0% | |

| 1910 | 4,679 | 17.0% | |

| 1920 | 5,367 | 14.7% | |

| 1930 | 7,993 | 48.9% | |

| 1940 | 9,495 | 18.8% | |

| 1950 | 13,052 | 37.5% | |

| 1960 | 18,991 | 45.5% | |

| 1970 | 26,360 | 38.8% | |

| 1980 | 32,845 | 24.6% | |

| 1990 | 44,922 | 36.8% | |

| 2000 | 68,816 | 53.2% | |

| 2010 | 108,755 | 58.0% | |

| Est. 2017 | 136,372 | [4] | 25.4% |

| Sources: U.S. Decennial Census[34] | |||

As of the 2010 census, there were 108,755 people residing in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 75.62% White, 15.18% Black / African American, 0.35% Native American, 3.36% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 2.79% from other races, and 2.65% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.93% of the population.

In the 2000 Census, There were 26,511 households out of which 30.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.8% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.6% were non-families. 28.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the city, the population was spread out with 22.7% under the age of 18, 20.5% from 18 to 24, 30.8% from 25 to 44, 17.3% from 45 to 64, and 8.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $39,705, and the median income for a family was $52,654. Males had a median income of $36,078 versus $26,531 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,219. About 8.2% of families and 14.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.0% of those under the age of 18 and 11.1% of those 65 and older.

Special census estimates in 2005 indicated 81,393 residents, and in 2006 the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey estimated a population of 92,559, with 35,842 households and 20,979 families in the city.[35] Murfreesboro's 2008 special census reported that the population had reached 100,575,[35] while preliminary information from the 2010 U.S. Census indicates a population of 108,755. In October 2017, the City of Murfreesboro started another special census. Given the continuous growth in the general area, the population is expected to exceed the 2016 estimate of 131,947.[36]

Education

Education within the city is overseen by Murfreesboro City Schools (MCS). MCS focuses on prekindergarten through sixth grade learning.[37] The city has 12 schools serving 7,200 students between grades pre-K through 6th.[26]:27 A 13th school, named Overall Creek Elementary was scheduled to be completed by 2014.[38] More than 68% of licensed employees have a master's degree or higher.[26]:27

Secondary schools are overseen by Rutherford County Schools, which has 42 schools and a student population of nearly 40,000.[39]:3

The Japanese Supplementary School in Middle Tennessee (JSMT, 中部テネシー日本語補習校 Chūbu Teneshī Nihongo Hoshūkō), a weekend Japanese education program, holds its classes at Peck Hall of the Middle Tennessee State University, while its school offices are in Jefferson Square.[40]

Parks

Cannonsburgh Village is a reproduction of what a working pioneer village would have looked like from the period of the 1830s to the 1930s. Visitors can view the grist mill, school house, doctor's office, Leeman House, Caboose, Wedding Chapel, and other points of interest. It is also home to the World's Largest Cedar Bucket.[41][42]

Old Fort Park is a 50-acre (200,000 m2) park which includes baseball fields, tennis courts, children's playground, an 18-hole championship golf course, picnic shelters and bike trail.[43]

Barfield Crescent Park is a 430-acre (1,700,000 m2) facility with eight baseball fields, 7 miles (11 km) of biking/running trails, an 18-hole championship disc golf course, and ten picnic shelters.[44]

Murfreesboro Greenway System is a system of greenways with 12 miles (19 km) of paved paths and 11 trail heads.[45] In 2013, the city council approved a controversial 25-year "master plan" to extend the system by adding 173 miles worth of new greenways, bikeways and blueways at an estimated cost of $104.8 million.[46]

Culture

Music

Murfreesboro hosts several music-oriented events annually, such as the Main Street Jazzfest presented by MTSU's School of Music and the Main Street Association each May.[41][47] For over 30 years, Uncle Dave Macon Days has celebrated the musical tradition of Uncle Dave Macon. This annual July event includes national competitions for old-time music and dancing.[41][48]

Murfreesboro also hosts an annual DIY not-for-profit music festival called Boro Fondo, which is also a bike tour and local artist feature.[49] Boro Fondo has previously featured Julien Baker's old band, The Star Killers.[50]

Because of MTSU's large music program, the city has fostered a number of bands and songwriters, including: Julien Baker, The Protomen, The Tony Danza Tapdance Extravaganza, A Plea for Purging, Self, Fluid Ounces, The Katies, Count Bass D, Destroy Destroy Destroy and The Features.

Arts

The Murfreesboro Center for the Arts, close to the Square, entertains with a variety of exhibits, theatre arts, concerts, dances, and magic shows.[41] Murfreesboro Little Theatre has provided the community with popular and alternative forms of theatre arts since 1962.[51]

Murfreesboro's International FolkFest began in 1982 and is held annually during the second week in June. Groups from countries spanning the globe participate in the festival, performing traditional songs and dances while attired in regional apparel.[52]

The MTSU Student Film Festival showcases student-submitted films annually during the second week in April.[53][54]

Other organizations include Youth Empowerment through Arts and Humanities[55] and the Murfreesboro Youth Orchestra.[56]

Museums

The Discovery Center at Murfree Spring is a nature center and interactive museum focusing on children and families. The facility includes 20 acres (8 ha) of wetlands with a variety of animals.[57]

Bradley Academy Museum contains collectibles and exhibits of the first school in Rutherford County. This school was later renovated to become the only African American school in Murfreesboro, which closed in 1955.[41][58]

The Stones River National Battlefield is a national park which memorializes the Battle of Stones River, which took place during the American Civil War during December 31, 1862, to January 3, 1863. The grounds include a museum, a national cemetery, monuments, and the remains of a large earthen fortification called Fortress Rosecrans.[41]

Oaklands Historic House Museum is a 19th-century mansion which became involved in the Civil War. It was occupied as a residence until the 1950s, after which it was purchased by the City of Murfreesboro and renovated into a museum by the Oaklands Association.[41][59]

Earth Experience: The Middle Tennessee Museum of Natural History is the only natural history museum in Middle Tennessee. The museum opened in September 2014 and features more than 2,000 items on display, including a complete replica Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton.[60][61]

Shopping

There are two main malls located within the city limits. Stones River Mall is a traditional enclosed mall, featuring stores and restaurants such as Forever 21, Aéropostale, Journey's, Hot Topic, Agaci, Dillard's, Buckle, Books-A-Million, Olive Garden, and T.G.I. Friday's.

The Avenue Murfreesboro is an outdoor lifestyle center with such shops as American Eagle, Hollister, Best Buy, Belk, Petco, Dick's Sporting Goods, Express, Mimi's Cafe, Romano's Macaroni Grill, and LongHorn Steakhouse.

The Historic Downtown Murfreesboro district also offers a wide variety of shopping and dining experiences that encircle the pre-Civil War Courthouse.[62]

Media

Murfreesboro is serviced by the following media outlets:

Newspapers:

- The Daily News Journal

- The Murfreesboro Post

- The Murfreesboro Pulse

- Sidelines – MTSU student newspaper

- Rutherford Source

Radio:

- WGNS – Talk radio

- WMOT – MTSU public radio station

- WMTS-FM – MTSU free-form student-run station

- WRHW-LP - 3ABN Radio Christian

TV:

- City TV Murfreesboro, Channel 3 – Government-access television channel

- MT10, Channel 10 – MTSU student-run educational-access television channel

- WETV-LP, Channel 11 – Provides audio/video simulcast of talk radio station WGNS

Mosque controversy

Beginning in 2010, the Islamic Center of Murfreesboro faced protests related to its plan to build a new 12,000-square-foot (1,100 m2) mosque. The county planning council had approved the project, but opposition grew in the aftermath, affected by this being a year of elections. Signs on the building site were vandalized, with the first saying "not welcome" sprayed across it and the second being cut in two.[63] Construction equipment was also torched by arsonists.[64]

In August 2011, a Rutherford County judge upheld his previous decision allowing the mosque to be built, noting the US constitutional right to religious freedom and the ICM's observance of needed process.[65] The Center has a permanent membership of around 250 families and a few hundred students from the university.[66] The case ultimately attracted national media attention as an issue of religious freedom.

Points of interest

- Discovery Center at Murfree Spring

- Geographic center of Tennessee

- Middle Tennessee State University

- Oaklands Historic House Museum

- Stones River Greenway Arboretum

- Stones River National Battlefield

- Cannonsburgh Village

Murfreesboro is the home of a Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy (CMOP). It is part of an initiative by the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide mail order prescriptions to veterans using computerization at strategic locations throughout the United States. It is located on the campus of the Alvin C. York Veterans Hospital.

The City Center building (also known as the Swanson Building) is the tallest building in Murfreesboro. Located in the downtown area it was built by Joseph Swanson in 1989.[67] It has 15 floors, including a large penthouse, and stands 211 feet (64 m) tall.[68] As a commercial building its tenants include Bank of America and is the headquarters for the National Healthcare Corporation (NHC).

Economy

Top employers

According to Murfreesboro's 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[69] the top employers in Rutherford County are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nissan | 7,500 |

| 2 | Rutherford County government and schools | 6,073 |

| 3 | Middle Tennessee State University | 2,205 |

| 4 | National Healthcare | 2,071 |

| 5 | City of Murfreesboro government and schools | 1,912 |

| 6 | State Farm Insurance | 1,662 |

| 7 | Ingram Content Group | 1,500 |

| 8 | Alvin C. York Veterans Administration Medical Center | 1,461 |

| 9 | Asurion | 1,250 |

| 10 | Amazon.com | 1,200 |

Notable people

- Jerry Anderson (1953–1989), football player

- Toni Baldwin (born 1995), singer and songwriter

- Rankin Barbee (1874–1958), journalist and author

- Ronnie Barrett (born 1954), firearms manufacturer

- James M. Buchanan (1919–2013), economist

- Reno Collier, stand-up comedian

- Colton Dixon (born 1991), singer

- Will Allen Dromgoole, (1860–1934), author and poet

- Harold Earthman (1900–1987), politician

- Corn Elder (born 1994), football player

- Jeff Givens (died 2013), horse trainer

- Bart Gordon (born 1949), politician and lawyer

- Susan Harney (born 1946), actress

- Joe Black Hayes (1915–2013), football player

- Yolanda Hughes-Heying (born 1963), professional female bodybuilder

- Robert James (born 1947), football player

- Marshall Keeble (1878–1962), African American preacher

- Muhammed Lawal (born 1981), mixed martial artist

- Andrew Nelson Lytle (1902–1995), novelist, dramatist, essayist and professor

- Jean MacArthur (1898–2000), wife of U.S. Army General of the Army Douglas MacArthur

- Bayer Mack (born 1972), award-nominated filmmaker, journalist and founder of Block Starz Music.

- Matt Mahaffey (born 1973), record producer and recording engineer

- Philip D. McCulloch Jr. (1851–1928), politician

- Ridley McLean (1872–1933), United States Navy Rear Admiral

- Judith Ann Neelley (born 1964), double murderer

- William Northcott (1854-1917), lieutenant governor of Illinois

- Andre Alice Norton (1912-2005), author of science fiction and fantasy

- Joseph B. Palmer (1925–1990), lawyer, legislator, and soldier

- Sarah Childress Polk (1803–1891), First Lady of the United States

- Patrick Porter, singer-songwriter

- David Price (born 1985), Major League Baseball pitcher

- Grantland Rice (1880–1954), iconic sportswriter, journalist and poet

- Mary Scales (1928–2013), professor and civic leader

- Robert W. Scales (1926–2000), Vice-Mayor of Murfreesboro

- Margaret Rhea Seddon (born 1947), NASA astronaut

- Adam Smith (born 1990), Arena Football League player

- Chuck Taylor (born 1942), Major League Baseball relief pitcher

- Chris Young (born 1985), country music artist

Notable bands

- Destroy Destroy Destroy, American heavy metal band

- De Novo Dahl, Indie rock band

- Feable Weiner, American power pop band

- Fluid Ounces, American power pop band

- Self, American alternative pop/rock band

- The Katies, American power pop band

- The Plain, American rock band

- The Tony Danza Tapdance Extravaganza, American mathcore band

- Velcro Stars, Indie pop band

See also

References

- ↑ Broden, Scott (April 30, 2014). "Mayor McFarland to take oath of office Thursday". The Daily News Journal. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Broden, Scott (February 17, 2017). "Murfreesboro vice mayor adds to family legacy". The Daily News Journal. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ↑ "State of Tennessee Incorporated Places - Current/BAS17". United States Census Bureau. January 1, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "QuickFacts: Murfreesboro city, Tennessee". United States Census Bureau. 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Population and Population Centers by State: 2000". Census.gov. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- ↑ Solomon, Christopher (2010). "America's Fastest-Growing Cities". MSN Real Estate. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ↑ "MTSU tops in Tennessee Board of Regents enrollment". September 16, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Best places to live 2006: Murfreesboro, TN snapshot". CNN.com. 2006. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Murfreesboro a 'Best Place' to live". Nashville Business Journal. July 17, 2006. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Geological Survey Bulletin, no. 258 (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 218. OCLC 1156805.

- ↑ "History of Murfreesboro, TN". MurfreesboroTN.gov. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Battle Summary: Stones River". US National Park Service. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ "TN Encyclopedia: FORTRESS ROSECRANS". Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ↑ "Facts". Middle Tennessee State University. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ↑ "Murfreesboro History". City of Murfreesboro. 2008. Archived from the original on September 29, 2010.

- ↑ Westbrooks, W. H. (Winter 1973). "Mayors of Murfreesboro, 1818-1973". Publication No. 2. Murfreesboro, TN: Rutherford County Historical Society. pp. 37–38 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Pittard, Mabel (1984). "Appendix B: Mayors of Murfreesboro". In Corlew III, Robert E. Rutherford County. Tennessee County History Series. Memphis State University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 0-87870-182-6. OCLC 6820526 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 "Former mayors honored with street names". Murfreesboro Post. September 8, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Update: Former Mayor Joe B. Jackson dies". Murfreesboro Post. April 22, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ↑ Gordon, Bart (May 7, 1998). "Honoring the Distinguished Career of Mayor Joe B. Jackson". Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 105th Congress, Second Session. 144. Government Printing Office. p. 8577.

- ↑ Fagan, Jonathon (April 27, 2014). "End of 'The Bragg Era'". The Murfreesboro Post. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Mayor: Shane McFarland". City of Murfreesboro. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "2013–14 Budget". City of Murfreesboro. 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Lytle Creek". MurfreesboroTN.gov. November 3, 2009. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Understanding Town Creek". MurfreesboroTN.gov. 2008. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Town Creek, Murfreesboro Tennessee". EPA.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ↑ Davis, Doug (April 17, 2009). "Damage estimates hit $41.8M". The Daily News Journal. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ↑ "'Rover' bus service set to begin in early April". MurfreesboroTN.gov. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ↑ Hutchens, Turner (January 5, 2007). "Work begins on Rover bus fleet". Daily News Journal.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017. 2017 Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- 1 2 Hudgins, Melinda (July 1, 2009). "'Boro ranks 12th in U.S. for growth". Daily News Journal. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ "'Be Murfreesboro, Be Counted': Special Census available online". City of Murfreesboro. November 28, 2017. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Schools". Murfreesboro City Schools. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ↑ Amanda Haggard (August 13, 2013). "City board names school Overall Creek". Daily News Journal. Archived from the original on August 17, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ↑ "2013 Fact Book". Rutherford County Schools. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ↑ "所在地・連絡先" (Archive). Japanese Supplementary School in Middle Tennessee. Retrieved on April 5, 2015. "[補習校] Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU) Peck Hall 住所:1301 East Main Street Murfreesboro, TN 37132" (PDF Map/Archive) and "住所:805 South Church Street Jefferson Square, Suite 8 Murfreesboro, TN 37130"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Littman, Margaret (2013). Tennessee. Moon Handbooks. Avalon Travel. pp. 271–272. ISBN 1612381502.

- ↑ "Cannonsburgh Village". City of Murfreesboro. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Old Fort Park". City of Murfreesboro. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008.

- ↑ "Barfield Crescent Park". City of Murfreesboro. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Murfreesboro Greenway system". City of Murfreesboro. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Concerns and Enthusiasm Over Greenway Expansion Clash at City Council Meeting". WGNS. March 7, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Main Street Murfreesboro releases lineup for JazzFest". Southern Manners. March 10, 2014. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Uncle Dave Macon Days celebrates 36 years". Murfreesboro Post. June 26, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Murfreesboro's music festival releases lineup, itinerary". Rutherford Source. April 17, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Sad songs make Julien Baker feel better". The Daily News Journal. November 20, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ Willard, Michelle (July 25, 2013). "Murfreesboro Little Theatre wraps up 50th season". Murfreesboro Post. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Kemph, Marie (June 10, 2012). "International Folkfest celebrates diversity". Murfreesboro Post. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "14th Annual MTSU Student Film Festival". MTSU.edu. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "MTSU student film fest returns". Murfreesboro Post. February 16, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Paulson, Dave (December 15, 2009). "YEAH offers Murfreesboro youths empowerment through arts". The Tennessean. Music. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Murfreesboro Youth Orchestra". Now Playing Nashville. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Discovery Center adds Lifelong Learning classes". The Daily News Journal. February 21, 2014. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ West, Mike (January 24, 2010). "Bradley Academy dates back to 1811". Murfreesboro Post. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ "History of Oaklands Plantation". Oaklands Historic House Museum. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ De Gennaro, Nancy (September 8, 2014). "Earth Experience: Museum now open". Daily News Journal. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Revill, Caleb (February 24, 2017). "'Rock on': Murfreesboro's Museum of Natural History". MTSU Sidelines. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Main Street Murfreesboro". DowntownMurfreesboro.com. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ Kauffman, Elizabeth (August 19, 2010). "In Murfreesboro, Tenn.: Church 'Yes,' Mosque 'No'". Time. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Fire at Tenn. Mosque Building Site Ruled Arson". Associated Press via CBS News. August 30, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ Broden, Scott (August 31, 2011). "Judge upholds ruling for Murfreesboro mosque". The Tennessean. Gannett Tennessee. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ↑ Blackburn, Bradley (June 18, 2010). "Plan for Mosque in Tennessee Town Draws Criticism from Residents". ABC News. ABC News. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ↑ "100 E Vine Street – City Center". Showcase.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011.

- ↑ "City Center". Emporis.com. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report – Fiscal Year June 30, 2014". City of Murfreesboro. January 27, 2015. p. 153. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Murfreesboro, Tennessee. |